Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the performance of Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) applied to spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) volume datasets of the normal fetal heart in generating standard fetal echocardiography views.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study of patients with normal fetal hearts (19-30 gestational weeks), one or more STIC volume datasets were obtained of the apical four-chamber view. Each STIC volume successfully obtained was evaluated by STICLoop™ to determine its appropriateness before applying the FINE method. Visualization rates for standard fetal echocardiography views using diagnostic planes and/or Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance®) were calculated.

Results

One or more STIC volumes (n=463 total) were obtained in 246 patients. A single STIC volume per patient was analyzed using the FINE method. In normal cases, FINE was able to generate nine fetal echocardiography views using: 1) diagnostic planes in 76-100% of cases; 2) VIS-Assistance® in 96-100% of cases; and 3) a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® in 96-100% of cases.

Conclusion

FINE applied to STIC volumes can successfully generate nine standard fetal echocardiography views in 96-100% of cases in the second and third trimesters. This suggests that the technology can be used as a method to screen for congenital heart disease.

Keywords: 4D, cardiac, fetal heart, prenatal diagnosis, spatiotemporal image correlation, STIC, STICLoop™, ultrasound, Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance, VIS-Assistance®

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality among those born with birth defects [1], and represents the most prevalent organ-specific birth defect [2]. However, the prenatal diagnosis of CHD remains suboptimal, with sensitivities ranging from 22.5% to 52.8% [3-6]. Since most cases of CHD occur in pregnancies without risk factors [7], midtrimester screening for CHD is the most rational approach for the detection of cardiac anomalies [8-11]. Professional organizations have recommended guidelines for sonographic examination of the fetal heart [12,13], which reflect current knowledge about the prenatal detection of CHD. For example, the addition of outflow tract views to the four-chamber view in cardiac screening is an important step forward to improve such detection [12,13].

Volumetric sonography and specifically, four-dimensional (4D) ultrasound with spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) [14-17] facilitates examination of the fetal heart [14,15,18-41], and has been proposed in both cardiac screening and prenatal diagnosis of CHD [16,25,42-55], because it improves the ability to identify complex intracardiac relationships, and can shorten the examination time [14,22]. However, the optimal method to interrogate STIC volume datasets remains a challenge, and several algorithms have therefore been proposed for this purpose [15,18,21,24,28,31,33].

Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) has recently emerged as a novel approach to examine the fetal heart after a STIC volume has been acquired [56-58]. Such method allows the automatic generation and display of nine standard fetal echocardiography views in normal hearts, including those universally recommended by professional organizations, such as the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) and International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) [59,60]. Through the use of Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance®) which is a feature of FINE, operator-independent sonographic navigation and exploration of surrounding structures in each of the nine cardiac diagnostic planes is also possible [56-58], and this has been proposed to be of value in reducing the false-positive rate and improving the quality of the examination.

In the first report on the FINE method, there was successful generation of nine fetal echocardiography views in 98-100% of normal cases, using a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® [56]. The authors concluded that this method can simplify examination of the fetal heart, and reduce the operator dependency associated with manipulation and analysis of STIC volume datasets [56]. Recently, Garcia et al. reported that in the second and third trimesters, one or more STIC volumes could be prospectively obtained in 72.5% of women attending a prenatal clinic, and that 96.2% of such volumes were appropriate for analysis using FINE [58]. While these findings are encouraging since it suggests that nearly three-fourths of patients can be examined using the FINE method, further prospective studies are required to determine the frequency with which fetal echocardiography views can be obtained using FINE in different populations. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to prospectively evaluate the performance of the FINE method in successfully generating nine standard fetal echocardiography views when applied to STIC volume datasets.

METHODS

Subjects

In this prospective cohort study, women having singleton fetuses with normal fetal hearts between 19-30 gestational weeks underwent 4D sonography with STIC volume acquisition. The study was conducted at the Unit of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Department of Women's and Children's Health, AOP, Padua, Italy. All patients were enrolled in a research protocol approved by the local Ethics Committee, and provided written informed consent for the use of ultrasound images for research purposes. The hospital has a Federalwide Assurance (FWA) negotiated with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The research protocol was considered to convey less than minimal risk, as it only required sonographic examination.

STIC Volume Acquisition

Using STIC technology (Voluson E8 Expert; GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria), 4D volume datasets of the fetal heart (1-5 per patient) were obtained from an apical four-chamber view using a curved array transducer (4-8 MHz) by means of transverse sweeps through the fetal chest. The ultrasound examination was conducted using settings for fetal echocardiography, with adjustments to obtain clear two-dimensional (2D) images. The frame rate was maximized by decreasing the depth, narrowing the sector width, and placing a single focal zone at, or below the level of the fetal heart. The acquisition time was set for 10 seconds, and the angle of acquisition ranged between 20° and 45°, depending upon the gestational age. The goal was to set an acquisition angle at least 5 degrees more than the value of the gestational age in weeks. Mothers were asked to temporarily suspend breathing movements during the STIC volume acquisition. Volumes were obtained in the absence of fetal breathing or gross movements, as well as hiccups. Attempts were made to acquire STIC volume datasets when the fetal spine was located between the 5- and 7 o'clock positions, to reduce the likelihood of acoustic shadowing derived from the spine. Optimally, STIC volumes were obtained when there was a clearly visible transverse aortic arch [56].

Volumes were saved onto the hard drive of the ultrasound machine when examination of the multiplanar display demonstrated the following: 1) normal fetal heart rate; 2) fetal upper mediastinum and stomach present and visualized within the STIC volume; 3) minimal or no motion artifacts observed in the sagittal plane; and 4) minimal or absent acoustic shadowing so as not to hinder visualization of cardiac structures [56].

STICLoop™ Evaluation

All saved STIC volume datasets were then imported into a software system for analysis (SONOCUBIC FINE™ Classic Blue Series; Version 2013.04.05; Medge Platforms Inc., New York, NY, USA), which was installed on a SONY VAIO PCG 71211M desktop computer (SONY Corp., Minato, Tokyo, Japan), using the Operative System Microsoft Windows 7 PRO 64-bit Service pack (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Once a STIC volume is loaded into this software system, it is immediately converted into a two-dimensional cineloop that automatically scrolls in a continuous fashion (i.e. STICLoop™) [56]. This tool allows the sonologist to determine the appropriateness of STIC volume datasets before applying the FINE method [52]. With STICLoop™, the image on the screen begins with the initial frame that was obtained by the mechanical probe, and automatic scrolling through all the frames occurs until the last frame acquired in the sweep is reached [56]. We used a cine-rate of 8-12 loops/min to evaluate all the STIC volumes. Using STICLoop™, the criteria to define appropriate STIC volumes were the following: 1) fetal spine located between the 5- and 7-o'clock positions (reducing the possibility of shadowing from the ribs or spine); 2) minimal or absent shadowing (including the three vessels and trachea view, 3VT); 3) adequate image quality; 4) upper mediastinum and stomach included within the volume; 5) minimal or no motion artifacts observed in the loop (i.e. smooth sweep without evidence of abrupt jumps or discontinuous movements); 6) chest circumference contained within the region of interest; 7) sequential axial planes parallel to each other, similar to a sliced loaf of bread (i.e. no “drifting spine” from the four-chamber view down to the stomach); 8) no observed azimuthal issues or tilted planes (i.e. atria/ventricles do not appear foreshortened in the four-chamber view); and 9) minimal or no motion artifacts (observed in the sagittal plane) [56]. The sonologist determines whether STIC volumes are appropriate by: 1) observing the scrolling frames on the screen and evaluating for criteria 1 through 8; and 2) clicking on the cross-section of the fetal aorta, so that the displayed sagittal plane of the heart can be evaluated for motion artifacts (criteria 9) (Videoclip S1). From all STIC volumes determined to be appropriate using STICLoop™, only a single volume per patient was chosen for analysis using the FINE method.

Testing of the FINE Method

After marking seven anatomical structures of the fetal heart using the Anatomic Box® feature, nine standard fetal echocardiography views are automatically generated and displayed by FINE (as diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance®) [56]. The seven structures in sequential order are: 1) cross-section of the aorta at the level of the stomach; 2) cross-section of the aorta at the level of the four-chamber view; 3) crux; 4) right atrial wall; 5) pulmonary valve; 6) cross-section of the superior vena cava; and 7) transverse aortic arch. It is noteworthy that FINE helps sonologists to correctly identify and mark such anatomical structures in the following manner [56,57]: 1) a menu and reference image is displayed for each anatomical structure to be marked, and the order of marking is also specified; 2) the software system automatically scrolls through the STIC volume to the level of the most likely location of the anatomical structure to be marked; and 3) the software system recognizes the cardiac phase, which facilitates marking of anatomical structures (e.g. automatically closes the pulmonary valve).

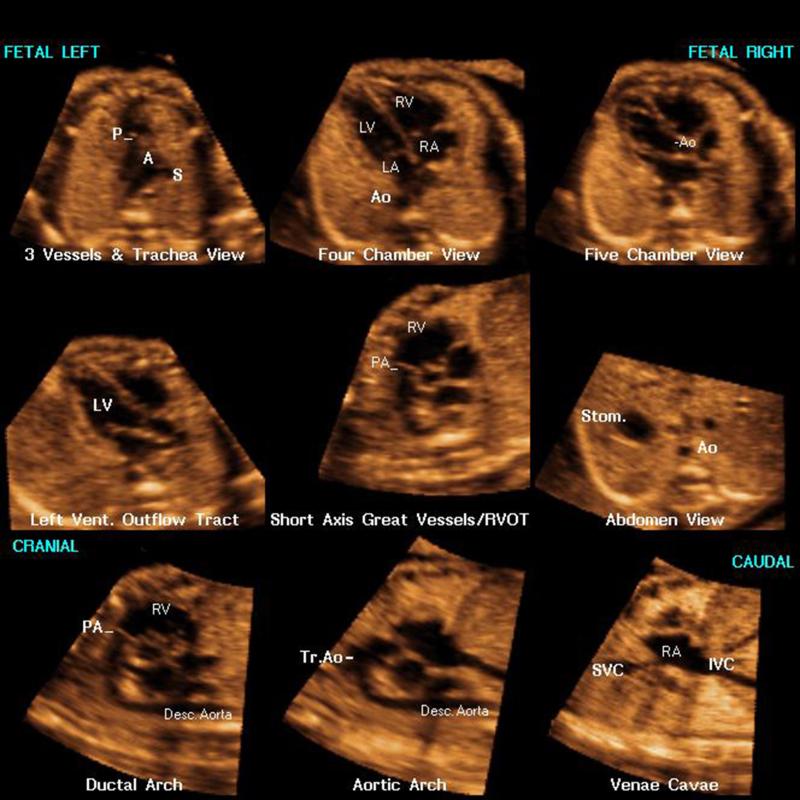

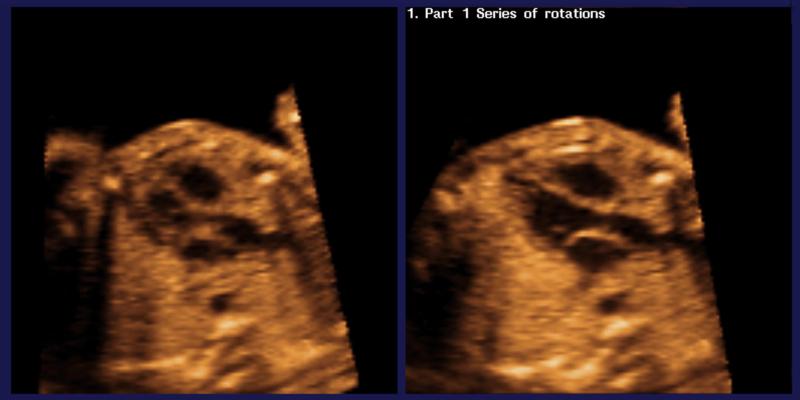

The nine fetal echocardiography views generated are: 1) four chamber; 2) five chamber; 3) left ventricular outflow tract; 4) short-axis view of great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract; 5) 3VT; 6) abdomen/stomach; 7) ductal arch; 8) aortic arch; and 9) superior and inferior venae cavae. If an operator is not familiar with the cardiac structures for marking and marks them incorrectly, FINE may not be successful in generating fetal echocardiography views [56]. Yet, in this situation the method can still be successful depending upon which structure(s) is being marked, the degree of “incorrectness” in marking structures (e.g. being slightly off vs. marking the wrong structure completely), and the echocardiography view being generated (e.g. abdomen/stomach). The nine fetal echocardiography views are displayed simultaneously in a single template (as nine diagnostic planes) approximately 3 seconds after the marking process is completed (Figure 1, Videoclip S2). For each diagnostic plane, VIS-Assistance® may also be activated. This “virtual” sonographer tool scans the STIC volume in a targeted approach (as a videoclip) to allow the complexity of the fetal heart to be studied in greater detail [56,57]. In other words, VIS-Assistance® allows operator-independent sonographic navigation and exploration of surrounding structures in each of the nine cardiac diagnostic planes (e.g. left ventricular outflow tract) [56,57]. VIS-Assistance® also improves the success of obtaining the fetal echocardiography view of interest (Figure 2, Videoclip S3).

Figure 1.

Spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) volume dataset of the fetal heart showing nine cardiac diagnostic planes displayed automatically in a single template through Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE). There is automatic labeling (through intelligent navigation) of each echocardiography view (i.e. diagnostic plane), anatomical structures, fetal left and right sides, and cranial and caudal ends (also see Videoclip S2). A, transverse aortic arch; Ao, aorta; Desc., descending; IVC, inferior vena cava; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; P, pulmonary artery; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; S, superior vena cava; Stom., stomach; SVC, superior vena cava; Tr., transverse; Vent., ventricular.

Figure 2.

Spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) volume dataset of the fetal heart showing the left ventricular outflow tract view through the Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) method. The left ventricular outflow tract was not successfully obtained using the diagnostic plane (left image). However, after Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance®) was activated, the automatic navigational movements allowed the left ventricular outflow tract to be successfully obtained (right image). Also see videoclip S3.

Using the FINE method, we determined the frequency of generating nine fetal echocardiography views using diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance®. For four cardiac VIS-Assistance® views (3VT, left ventricular outflow tract, short-axis view of great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract, and abdomen/stomach), VIS-Assistance® was considered successful in depicting the echocardiography view if certain anatomical structures were also visualized: 1) 3VT: three-vessel view, pulmonary valve and transverse aortic arch view; 2) left ventricular outflow tract: mitral valve, aortic valve, and ventricular septum; 3) short-axis view of great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract: pulmonary valve and tricuspid valve; and 4) abdomen/stomach: stomach and four-chamber view (to determine situs) [56].

For each STIC volume dataset, we also determined the following: 1) maximum number of fetal echocardiography views successfully obtained through diagnostic planes or VIS-Assistance®; and 2) success rate of obtaining four fetal echocardiography views (four chamber; left ventricular outflow tract; short-axis view of great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract; and abdomen/stomach) through diagnostic planes or VIS-Assistance®.

Intelligent and Marking Alerts

Since the original report on FINE [56], the same inventors subsequently developed Intelligent Alerts as part of this method to notify the sonologist about potential issues with the STIC volume dataset. Alerts are comprised of captions and/or a movie which automatically appear: 1) during the process of marking anatomical structures of the fetal heart; and 2) in specific situations. There are three types of intelligent alerts: 1) Breech Alert: notifies the user that the fetus appears to be in a breech presentation. The system asks if the STIC volume can be reoriented as if the fetus is in a “vertex” presentation. If the user clicks “Yes”, the system automatically realigns the volume dataset, and reorients and standardizes the anatomical position so that the fetus is “converted” to a vertex presentation; 2) Possible Drifting Spine Alert: notifies the user that there may be a “drifting” fetal spine in the STIC volume dataset (i.e. when the spine location migrates on the screen). The caption also states that marking of anatomical structures may be difficult, and successful visualization of echocardiography views may be affected; and 3) Spine Location Alert: notifies the user that the fetal spine appears to be located at a position (e.g. 8-o'clock) that is different from what is recommended (i.e. between 5- and 7-o'clock). The caption also states that this STIC volume is not recommended, and the spine location may lead to shadowing and suboptimal image quality. It is noteworthy that once a spine location alert has appeared, three Marking Alerts will next appear in sequence (Pulmonary Valve, Superior Vena Cava, and Transverse Aortic Arch Alerts). Such marking alerts are comprised of captions/movies which notify the user that fetal anatomical structures for marking (e.g. pulmonary valve) may be in a different location than what is expected.

Based upon how the alerts were designed, if appropriate STIC volume datasets have been obtained by a sonologist, the prevalence of alerts is expected to be low (one exception is the breech alert). It has been the inventors’ observation that for most sonologists, the appearance of alerts tends to be disconcerting and leads to an improvement in the STIC volume acquisition technique to avoid such alerts from appearing in the future. For the current study, we recorded both the number, and type of alerts which automatically appeared while marking anatomical structures of the fetal heart.

RESULTS

STIC volumes and alerts

One or more STIC volumes (n=463) were acquired in 246 pregnancies with a normal fetal heart, as determined by 2D sonographic examination. The gestational age distribution of patients at which STIC volumes were acquired was: 1) 19-22 weeks (n=167); 2) 23-26 weeks (n=60); and 3) 27-30 weeks (n=19). The median (interquartile range) gestational age was 21 (20-23) weeks. From the STIC volumes determined to be appropriate using STICLoop™, only a single volume per patient was selected for analysis using the FINE method. When there were multiple appropriate STIC volumes available per fetus, we chose the dataset that was considered to be of highest quality.

During the process of marking anatomical structures of the fetal heart in the STIC volume dataset, an intelligent alert appeared in 39.4% (97/246) of cases: 1) breech alert (n=74; 30.1%); 2) spine location alert (n=21; 8.5%); and 3) possible drifting spine alert (n=2; 0.8%). Therefore, 30.1% of fetuses were in an original breech presentation, so that the cardiac apex was originally pointing to the right side of the monitor screen. Yet, the breech alert allowed reorientation of the STIC volume so that the fetus would be in a “vertex” presentation. This is done so that: 1) marking anatomical structures is easier, since each structure is expected to be in the same location on the screen; and 2) structures and fetal anatomy would be more easily recognizable by users [56]. The spine location alert appeared in only 8.5% (n=21) of cases, and the alert was automatically activated during the marking process because the fetal spine in the STIC volume was located in a position other than between 5- and 7-o'clock: 1) 7 to 8-o'clock (47.6%; n=10); 2) 8-o'clock (28.6%; n=6); 3) 4 to 5 o'clock (14.3%; n=3); and 4) 4-o'clock (9.5%; n=2). Therefore, when evaluating STIC volumes via STICLoop™, we had correctly identified that in 91.5% (225/246) of the volumes, the fetal spine was located between the 5- and 7-o'clock positions. For each spine location alert that was automatically activated, three marking alerts (pulmonary valve, superior vena cava, and transverse aortic arch alerts) also appeared next in sequence. Such alerts noted that fetal anatomical structures for marking (e.g. transverse aortic arch) could be in a different location than expected, since the fetal spine was not located between the 5- and 7-o'clock positions.

Performance of FINE method to generate fetal echocardiography views

To evaluate the performance of the FINE method, we evaluated a total of 4428 images: 2214 diagnostic planes (246 STIC volumes × 9) and 2214 VIS-Assistance® videoclips (246 STIC volumes × 9). The FINE method was able to generate nine fetal echocardiography views using: 1) diagnostic planes in 76-100% of cases; 2) VIS-Assistance® in 96-100% of cases; and 3) a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® in 96-100% of cases (Table 1). Figure 1 shows an example of nine cardiac diagnostic planes in a single template with the additional feature of automatic labeling through intelligent navigation [56]. This unique feature allows labeling to occur for the nine fetal echocardiography views (i.e. diagnostic planes), left and right side of the fetus, cranial and caudal ends, as well as the atrial and ventricular chambers, great vessels (aorta and pulmonary artery), superior and inferior vena cavae, and stomach [56]. Automatic labeling is an optional feature, and is activated by pressing a single button. Videoclip S2 demonstrates the same nine cardiac diagnostic planes both before, and after activation of automatic labeling.

Table 1.

Success rates of obtaining nine fetal echocardiography views after applying the Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) method to 246 normal spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) volume datasets using diagnostic planes and/or Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance®)

| Diagnostic plane (n=246) | VIS-Assistance® (n=246) | Diagnostic plane and/or VIS-Assistance® (n=246) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal echocardiography view | n (%) | 95% CI* | n (%) | 95% CI* | n (%) | 95% CI* |

| 1. Four-chamber | 229 (93) | 89 to 96 | 246 (100) | 98 to 100 | 246 (100) | 98 to 100 |

| 2. Five-chamber | 231 (94) | 90 to 96 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 |

| 3. LVOT | 225 (91) | 87 to 94 | 243 (99) | 96 to 99.7 | 243 (99) | 96 to 99.7 |

| 4. Short-axis view of great vessels/RVOT | 216 (88) | 83 to 91 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 |

| 5. 3VT | 226 (92) | 88 to 95 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 | 245 (99.6) | 98 to >99.9 |

| 6. Abdomen/Stomach | 246 (100)† | 98 to 100 | 246 (100)‡ | 98 to 100 | 246 (100) | 98 to 100 |

| 7. Ductal arch | 205 (83) | 78 to 88 | 239 (97) | 94 to 99 | 239 (97) | 94 to 99 |

| 8. Aortic arch | 214 (87) | 82 to 91 | 238 (97) | 94 to 98 | 238 (97) | 94 to 98 |

| 9. SVC/IVC | 187 (76) | 70 to 81 | 236 (96) | 93 to 98 | 236 (96) | 93 to 98 |

| • SVC | 230 (93) | 90 to 96 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| • IVC | 200 (81) | 76 to 86 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

The Wald method was used to calculate two-sided CIs for proportions expressed in the table; as the true proportion cannot exceed 100%, upper confidence limits are truncated at 100%.

Defined as visualization of the stomach in the diagnostic plane.

Defined as visualization of both the stomach and four-chamber view in VIS-Assistance® (to determine situs).

3VT, three-vessels and trachea; IVC, inferior vena cava; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; SVC, superior vena cava.

The maximum number of fetal echocardiography views successfully obtained through diagnostic planes or VIS-Assistance® for each normal STIC volume dataset (n=246) is displayed in Table 2. For diagnostic planes, 77% (n=189) of STIC volumes demonstrated either eight (33%; n=81) or all nine (44%; n=108) echocardiography views, while 13% (n=31) demonstrated seven views. For VIS-Assistance®, 97% (n=240) of STIC volumes demonstrated either eight (7%; n=18) or all nine (90%; n=222) echocardiography views, while the remaining 3% (n=6) demonstrated seven views.

Table 2.

Number of fetal echocardiography views obtained successfully through diagnostic planes or Virtual Intelligent Sonographer Assistance (VIS-Assistance®) for each normal spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) volume dataset (n=246)

| Number of views obtained (maximum = 9) | Diagnostic Planes (n=246) | VIS-Assistance® (n=246) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| 5 | 8 (3) | ------ |

| 6 | 17 (7) | ------ |

| 7 | 31 (13) | 6 (3) |

| 8 | 81 (33) | 18 (7) |

| All 9 views obtained | 108 (44) | 222 (90) |

| TOTAL | 246 (100) | 246 (100) |

For each normal STIC volume dataset (n=246), the success rate of obtaining the four-chamber view, left ventricular outflow tract view, short-axis view of the great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract and abdomen/stomach view was 80% (n=198) using diagnostic planes and 99% (n=243) using VIS-Assistance®.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of the study

The principal findings are: 1) nine fetal echocardiography views were generated by the FINE method using a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance in 96-100% of cases; 2) for each STIC volume dataset, 77% of volumes demonstrated either eight or all nine echocardiography views (via diagnostic planes), while 97% of volumes demonstrated either eight or all nine echocardiography views (via VIS-Assistance®); 3) for each STIC volume dataset, the success rate of obtaining four views (four chamber, left ventricular outflow tract, short-axis view of great vessels/right ventricular outflow tract, abdomen/stomach) was 80% and 99% using diagnostic planes and VIS-Assistance®, respectively; and 4) during the process of marking structures of the fetal heart in STIC volumes, an intelligent alert appeared in 39.4% (97/246) of cases. The majority of intelligent alerts were the breech alert type (76.3%; 74/97). Collectively, these findings indicate that FINE is a reliable method to obtain the cardiac views required for detailed examination of the fetal heart, and hence, may be used in prenatal screening for congenital heart disease.

The study in context

The invention of fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE) involved two phases (i.e. development and testing) [56]. During the first phase, the investigators used 51 STIC volume datasets from fetuses with a normal heart to determine a parsimonious set of anatomical landmarks that would produce a geometrical model of the fetal heart, and yield nine fetal echocardiography views [56]. In this development phase, the FINE method was able to generate nine cardiac views using a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® in 98-100% of cases [56]. For the second phase, the investigators then tested the FINE method on a new set of 50 STIC volume datasets of normal hearts from an independent set of patients to determine the validity of the method [56]. This was necessary to evaluate whether relationships among anatomical structures determined from the first 51 fetuses were maintained in a different fetal population. In this testing phase, the FINE method generated nine fetal echocardiography views using a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® in 98-100% of cases [56]. Since this original publication, Garcia et al. reported that STIC volumes appropriate for analysis using the FINE method could be obtained prospectively in the second and third trimesters in 72.5% of women attending a prenatal clinic [58]. The same authors also reported the success rate of obtaining nine standard fetal echocardiography views (98-100%) using diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance® in this population [58]. Thus far, work published on the FINE method has been generated in the same unit in Detroit, Michigan.

The study herein represents the first independent test of FINE's performance in a different ultrasound unit, in which data were obtained prospectively by different sonologists. It is noteworthy that our study includes nearly five times the number of patients (i.e. 246) that were studied for the testing phase of FINE in the original report [56]. Prior to initiation of the current study, the team in Padua, Italy was trained by the same investigators who invented the FINE method. Such training included: 1) attending theoretical lectures on FINE; 2) marking anatomical structures of the fetal heart in previously acquired STIC volume datasets; 3) acquisition of STIC volumes from normal fetal hearts under direct supervision; 4) review of such volumes using FINE; and 5) review of STIC volumes of CHD cases using FINE. After training was completed, the investigators in Padua conducted the study herein.

Clinical implications of the study

The challenges of prenatal screening for CHD using ultrasound are well known [5], with studies reporting low sensitivity (22.5-52.8%) in the detection of CHD, even when more than 90% of the population undergo sonographic examination [3-6]. Unfortunately, over the last two decades, the prenatal detection of CHD has not improved substantially, despite improved imaging techniques and equipment, as well as intense training of sonologists [61]. STIC technology enables acquisition of a volume dataset of the fetal heart, displaying a cine loop of a complete, single cardiac cycle in motion. Therefore, such technology has made it feasible to theoretically capture all the information (i.e. fetal cardiac anatomy) incorporated within the transducer sweep. Sonologists can then interrogate the volume dataset to examine anatomical areas of interest in planes of section other than the original acquisition plane [17]. However, “manual navigation” (e.g. operating the x, y, z controls, scaling, parallel shifting) [57] to retrieve and display all of the relevant cardiac views is difficult, time-consuming, operator dependent, and requires an in-depth knowledge about anatomy. As a result, algorithms based upon STIC have been developed over the years [15,18,21,24,28,31,33] to simplify and systematically extract information, and display cardiac planes with the objective of reducing operator dependency.

The FINE method represents a substantial advance compared to other techniques to obtain fetal cardiac views, since manual standardization or manipulation of the STIC volume dataset and reference planes is not required (e.g. manual rotation or alignment) [56]. Moreover, this automatic method: 1) allows successful display of cardiac diagnostic planes, despite different gestational ages and also in the presence of anatomical variability (e.g. cardiac axis and geometry); 2) is predictable (diagnostic planes are generated in a consistent manner) and adaptive (“fits” the anatomy of each particular fetus under examination); 3) includes the novel feature VIS-Assistance® (Figure 2, Videoclip S3); 4) allows automatic labeling of anatomical structures (Figure 1, Videoclip S2); 5) incorporates cardiac phase recognition technology; and 6) can be applied over a broad range of gestational ages [56]. Additional features of FINE developed recently include intelligent alerts (notifies the sonologist about potential issues with the STIC volume dataset), and marking alerts (notifies the user that fetal anatomical structures for marking may be in a different location than what is expected). As predicted, the prevalence of two types of intelligent alerts (i.e. spine location and possible drifting spine alerts) was low (9.3%) in the current study. This can be explained by the criteria for STIC volume acquisition, as well as the STICLoop™ criteria that were employed.

Our view is that FINE can complement and add to a sonologist's training and education, as well as increase the knowledge base of those performing fetal cardiac examinations. Indeed, we have received feedback from users that FINE is valuable as a teaching and training tool. For example, the marking process facilitates the learning of cardiac anatomy. Moreover, in cases of congenital heart disease, FINE allows multiple echocardiography views and anatomical abnormalities to be studied in detail [56].

Prior to implementing the FINE method in prenatal screening programs for CHD, a key question is whether the findings initially reported by the unit which developed FINE could be replicated by different sonologists located elsewhere. The current observation that nine standard fetal echocardiography views can be generated successfully using a combination of diagnostic planes and/or VIS-Assistance in 96-100% of cases in the second and third trimester provides evidence that this is the case.

Implications for future research

The next steps to be undertaken for application of the FINE method include evaluation of its diagnostic performance in cases of CHD (i.e. sensitivity and specificity). We believe that such studies are justified, based upon the data generated thus far [56,58]. There is already evidence that in cases of proven CHD, FINE is able to demonstrate abnormal cardiac anatomy in multiple echocardiography views displayed at the same time [56]. Moreover, for some CHD cases, VIS-Assistance® provides additional information that is not evident in the diagnostic planes [56].

Adequate education and training of sonologists is an essential step to assure that: 1) STIC volumes are appropriately acquired in the clinical setting and are of high quality [17,58,62,63]; 2) determination of the appropriateness of such volumes occurs (i.e. STICLoop™); and 3) there is maximal utilization of the features of the FINE method (e.g. VIS-Assistance®). We believe that a certification sprocess on the FINE method, similar to that already implemented for sonographic examination of less complex anatomical structures (e.g. nuchal translucency, uterine cervix) should be considered, given the complex anatomy of the fetal heart, challenges in the diagnosis of CHD, and the importance of prenatal diagnosis of CHD on short- and long-term outcomes [64-72].

CONCLUSION

Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) applied to STIC volumes can successfully generate nine standard fetal echocardiography views in 96-100% of cases in the second and third trimesters. Therefore, this technology is ready for evaluation as a method to screen for congenital heart disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An application for a patent (“Apparatus and Method for Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography”) has been filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and the patent is pending. Dr. Lami Yeo and Dr. Roberto Romero are co-inventors, along with Mr. Gustavo Abella and Mr. Ricardo Gayoso. The rights of Dr. Yeo and Dr. Romero have been assigned to Wayne State University, and NICHD/NIH, respectively. None of the authors has a financial relationship with either GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI or Medge Platforms, Inc., New York, NY. Roberto Romero has contributed to this work as part of his official duties as employee of the United States Federal Government.

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang Q, Chen H, Correa A, Devine O, Mathews TJ, Honein MA. Racial differences in infant mortality attributable to birth defects in the United States, 1989-2002. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:706–713. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Improved national prevalence estimates for 18 selected major birth defects--United States, 1999-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;54:1301–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chew C, Halliday JL, Riley MM, Penny DJ. Population-based study of antenatal detection of congenital heart disease by ultrasound examination. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:619–624. doi: 10.1002/uog.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoo NS, Van Essen P, Richardson M, Robertson T. Effectiveness of prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects in South Australia: a population analysis 1999-2003. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedberg MK, Silverman NH, Moon-Grady AJ, Tong E, Nourse J, Sorenson B, Lee J, Hornberger LK. Prenatal detection of congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2009;155:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto NM, Keenan HT, Minich LL, Puchalski MD, Heywood M, Botto LD. Barriers to prenatal detection of congenital heart disease: a population-based study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:418–425. doi: 10.1002/uog.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allan L. Antenatal diagnosis of heart disease. Heart. 2000;83:367–370. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson JN, Simpson LL, Abuhamad AZ. Screening for fetal heart disease with ultrasound. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:890–896. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200312000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smythe JF, Copel JA, Kleinman CS. Outcome of prenatally detected cardiac malformations. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1471–1474. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90903-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gembruch U. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:1283–1298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199712)17:13<1283::aid-pd296>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee W. Performance of the basic fetal cardiac ultrasound examination. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:601–607. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.9.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine AIUM practice guideline for the performance of obstetric ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1083–1101. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvalho JS, Allan LD, Chaoui R, Copel JA, DeVore GR, Hecher K, Lee W, Munoz H, Paladini D, Tutschek B, Yagel S. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): sonographic screening examination of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:348–359. doi: 10.1002/uog.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVore GR, Falkensammer P, Sklansky MS, Platt LD. Spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC): new technology for evaluation of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:380–387. doi: 10.1002/uog.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncalves LF, Lee W, Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J, Schoen ML, Falkensammer P, Treadwell M, Romero R. Four-dimensional ultrasonography of the fetal heart with spatiotemporal image correlation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1792–1802. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinals F, Poblete P, Giuliano A. Spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC): a new tool for the prenatal screening of congenital heart defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:388–394. doi: 10.1002/uog.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeo L, Romero R. How to acquire cardiac volumes for sonographic examination of the fetal heart (part 1). J Ultrasound Med. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.01081. DOI: 10.7863/ultra.16.01081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeVore GR, Polanco B, Sklansky MS, Platt LD. The ‘spin’ technique: a new method for examination of the fetal outflow tracts using three-dimensional ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:72–82. doi: 10.1002/uog.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaoui R, Hoffmann J, Heling KS. Three-dimensional (3D) and 4D color Doppler fetal echocardiography using spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:535–545. doi: 10.1002/uog.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goncalves LF, Romero R, Espinoza J, Lee W, Treadwell M, Chintala K, Brandl H, Chaiworapongsa T. Four-dimensional ultrasonography of the fetal heart using color Doppler spatiotemporal image correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:473–481. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Goncalves LF, Nien JK, Hassan S, Lee W, Romero R. A novel algorithm for comprehensive fetal echocardiography using 4-dimensional ultrasonography and tomographic imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:947–956. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.8.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yagel S, Cohen SM, Shapiro I, Valsky DV. 3D and 4D ultrasound in fetal cardiac scanning: a new look at the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:81–95. doi: 10.1002/uog.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molina FS, Faro C, Sotiriadis A, Dagklis T, Nicolaides KH. Heart stroke volume and cardiac output by four-dimensional ultrasound in normal fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:181–187. doi: 10.1002/uog.5374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzo G, Capponi A, Muscatello A, Cavicchioni O, Vendola M, Arduini D. Examination of the fetal heart by four-dimensional ultrasound with spatiotemporal image correlation during routine second-trimester examination: the ‘three-steps technique’. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;24:126–131. doi: 10.1159/000142142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tutschek B, Sahn DJ. Semi-automatic segmentation of fetal cardiac cavities: progress towards an automated fetal echocardiogram. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:176–180. doi: 10.1002/uog.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennasar M, Martínez JM, Olivella A, del Río M, Gómez O, Figueras F, Puerto B, Gratacós E. Feasibility and accuracy of fetal echocardiography using four-dimensional spatiotemporal image correlation technology before 16 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:645–651. doi: 10.1002/uog.6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uittenbogaard LB, Haak MC, Spreeuwenberg MD, van Vugt JM. Fetal cardiac function assessed with four-dimensional ultrasound imaging using spatiotemporal image correlation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:272–281. doi: 10.1002/uog.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeo L, Romero R, Jodicke C, Ogge G, Lee W, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Hassan S. Four-chamber view and ‘swing technique’ (FAST) echo: a novel and simple algorithm to visualize standard fetal echocardiographic planes. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:423–431. doi: 10.1002/uog.8840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen L, Mangers K, Grobman WA, Platt LD. Satisfactory visualization rates of standard cardiac views at 18 to 22 weeks’ gestation using spatiotemporal image correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1645–1650. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.12.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abuhamad A, Chaoui R. Three-dimensional fetal echocardiography: basic and advanced applications. In: Abuhamad A, Chaoui R, editors. A Practical Guide to Fetal Echocardiography: Normal and Abnormal Hearts. 2nd ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. pp. 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jantarasaengaram S, Vairojanavong K. Eleven fetal echocardiographic planes using 4-dimensional ultrasound with spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC): a logical approach to fetal heart volume analysis. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turan S, Turan OM, Ty-Torredes K, Harman CR, Baschat AA. Standardization of the first-trimester fetal cardiac examination using spatiotemporal image correlation with tomographic ultrasound and color Doppler imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:652–656. doi: 10.1002/uog.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeo L, Romero R, Jodicke C, Kim SK, Gonzalez JM, Ogge G, Lee W, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Hassan S. Simple targeted arterial rendering (STAR) technique: a novel and simple method to visualize the fetal cardiac outflow tracts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:549–556. doi: 10.1002/uog.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamill N, Yeo L, Romero R, Hassan SS, Myers SA, Mittal P, Kusanovic JP, Balasubramaniam M, Chaiworapongsa T, Vaisbuch E, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, Goncalves LF, Lee W. Fetal cardiac ventricular volume, cardiac output, and ejection fraction determined with 4-dimensional ultrasound using spatiotemporal image correlation and virtual organ computer-aided analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:76, e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luewan S, Yanase Y, Tongprasert F, Srisupundit K, Tongsong T. Fetal cardiac dimensions at 14-40 weeks’ gestation obtained using cardio-STIC-M. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:416–422. doi: 10.1002/uog.8961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araujo Junior E, Rolo LC, Rocha LA, Nardozza LM, Moron AF. The value of 3D and 4D assessments of the fetal heart. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:501–507. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S47074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barros FS, Moron AF, Rolo LC, Rocha LA, Martins WP, Tonni G, Nardozza LM, Araujo Júnior E. Fetal myocardial wall area: constructing a reference range by means of spatiotemporal image correlation in the rendering mode. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2015;37:44–50. doi: 10.1159/000363653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nardozza LM, Rolo LC, Araujo Júnior E, Hatanaka AR, Rocha LA, Simioni C, Ruano R, Moron AF. Reference range for fetal interventricular septum area by means of four-dimensional ultrasonography using spatiotemporal image correlation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2013;33:110–115. doi: 10.1159/000345650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viñals F. Current experience and prospect of internet consultation in fetal cardiac ultrasound. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;30:83–87. doi: 10.1159/000330113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godfrey ME, Messing B, Valsky DV, Cohen SM, Yagel S. Fetal cardiac function: M-mode and 4D spatiotemporal image correlation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012;32:17–21. doi: 10.1159/000335357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crispi F, Gratacós E. Fetal cardiac function: technical considerations and potential research and clinical applications. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012;32:47–64. doi: 10.1159/000338003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goncalves LF, Espinoza J, Romero R, Lee W, Beyer B, Treadwell MC, Humes R. A systematic approach to prenatal diagnosis of transposition of the great arteries using 4-dimensional ultrasonography with spatiotemporal image correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:1225–1231. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Lee W, Mazor M, Romero R. A novel method to improve prenatal diagnosis of abnormal systemic venous connections using three- and four-dimensional ultrasonography and “inversion mode.”. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:428–434. doi: 10.1002/uog.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghi T, Cera E, Segata M, Michelacci L, Pilu G, Pelusi G. Inversion mode spatio-temporal image correlation (STIC) echocardiography in three-dimensional rendering of fetal ventricular septal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:679–680. doi: 10.1002/uog.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paladini D, Sglavo G, Greco E, Nappi C. Cardiac screening by STIC: can sonologists performing the 20-week anomaly scan pick up outflow tract abnormalities by scrolling the A-plane of STIC volumes? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:865–870. doi: 10.1002/uog.6261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shih JC, Shyu MK, Su YN, Chiang YC, Lin CH, Lee CN. ‘Big-eyed frog’ sign on spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) in the antenatal diagnosis of transposition of the great arteries. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:762–768. doi: 10.1002/uog.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gindes L, Hegesh J, Weisz B, Gilboa Y, Achiron R. Three and four dimensional ultrasound: a novel method for evaluating fetal cardiac anomalies. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29:645–653. doi: 10.1002/pd.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennasar M, Martínez JM, Gómez O, Bartrons J, Olivella A, Puerto B, Gratacós E. Accuracy of four-dimensional spatiotemporal image correlation echocardiography in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:458–464. doi: 10.1002/uog.7720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volpe P, Tuo G, De Robertis V, Campobasso G, Marasini M, Tempesta A, Gentile M, Rembouskos G. Fetal interrupted aortic arch: 2D-4D echocardiography, associations and outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:302–309. doi: 10.1002/uog.7530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Espinoza J, Lee W, Comstock C, Romero R, Yeo L, Rizzo G, Paladini D, Viñals F, Achiron R, Gindes L, Abuhamad A, Sinkovskaya E, Russell E, Yagel S. Collaborative study on 4-dimensional echocardiography for the diagnosis of fetal heart defects: the COFEHD study. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1573–1580. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.11.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adriaanse BM, Tromp CH, Simpson JM, Van Mieghem T, Kist WJ, Kuik DJ, Oepkes D, Van Vugt JM, Haak MC. Interobserver agreement in detailed prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease by telemedicine using four-dimensional ultrasound with spatiotemporal image correlation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:203–209. doi: 10.1002/uog.9059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong Y, Liu T, Wu Y, Xu JF, Ting YH, Yeung Leung T, Lau TK. Comparison of real-time three-dimensional echocardiography and spatiotemporal image correlation in assessment of fetal interventricular septum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:2333–2338. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.695822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie ZP, Zhao BW, Yuan H, Hua QQ, Jin SH, Shen XY, Han XH, Zhou JM, Fang M, Chen JH. New insight from using spatiotemporal image correlation in prenatal screening of fetal conotruncal defects. Int J Fertil Steril. 2013;7:187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Wang Y, Sun W, Chen L, Zhao D, Zhan Y, Cai A. Four-dimensional echocardiography with spatiotemporal image correlation and inversion mode for detection of congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:1434–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barros FS, Rolo LC, Rocha LA, Martins WP, Nardozza LM, Moron AF, Da Silva Costa F, Araujo Junior E. Reference ranges for the volumes of fetal cardiac ventricular walls by three-dimensional ultrasound using spatiotemporal image correlation and virtual organ computer-aided analysis and its validation in fetuses with congenital heart diseases. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35:65–73. doi: 10.1002/pd.4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeo L, Romero R. Fetal intelligent navigation echocardiography (FINE): a novel method for rapid, simple, and automatic examination of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:268–284. doi: 10.1002/uog.12563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeo L, Romero R. Intelligent navigation to improve obstetrical sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1002/uog.12562. DOI: 10.1002/uog.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia M, Yeo L, Romero R, Haggerty D, Giardina I, Hassan SS, Chaiworapongsa T, Hernandez-Andrade E. Prospective evaluation of the fetal heart using Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1002/uog.15676. DOI: 10.1002/uog.15676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine AIUM practice guideline for the performance of fetal echocardiography. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1067–1082. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee W, Allan L, Carvalho JS, Chaoui R, Copel J, Devore G, Hecher K, Munoz H, Nelson T, Paladini D, Yagel S. ISUOG Fetal Echocardiography Task Force: ISUOG consensus statement: what constitutes a fetal echocardiogram? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:239–242. doi: 10.1002/uog.6115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trivedi N, Levy D, Tarsa M, Anton T, Hartney C, Wolfson T, Pretorius DH. Congenital cardiac anomalies: prenatal readings versus neonatal outcomes. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:389–399. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeo L, Romero R. How to acquire cardiac volumes for sonographic examination of the fetal heart. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:1021–1042. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.01081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeo L, Romero R. How to acquire cardiac volumes for sonographic examination of the fetal heart. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:1043–1066. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Reddy VM, Brook MM, Hanley FL, Silverman NH. Improved surgical outcome after fetal diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Circulation. 2001;103:1269–1273. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bonnet D, Coltri A, Butera G, Fermont L, Ke Bidois J, Kachaner J, Sidi D. Detection of transposition of the great arteries in fetuses reduces neonatal marbidity and mortality. Circulation. 1999;99:916–918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar RK, Newburger JW, Gauvreau K, Kamenir SA, Hornberger LK. Comparison of outcome when hypoplastic left heart syndrome and transposition of the great arteries are diagnosed prenatally versus when diagnosis of these two conditions is made only postnatally. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1649–1653. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verheijen PM, Lisowski LA, Stoutenbeek P, Hitchcock JF, Bennink GB, Meijboom EJ. Lactacidosis in the neonate is minimized by prenatal detection of congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19:552–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Franklin O, Burch M, Manning N, Sleeman K, Gould S, Archer N. Prenatal diagnosis of coartation of the aorta improves survival and reduces morbidity. Heart. 2002;87:67–69. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown KL, Ridout DA, Hoskote A, Verhulst L, Ricci M, Bull C. Delayed diagnosis of congenital heart disease worsens preoperative condition and outcome of surgery in neonates. Heart. 2006;92:1298–1302. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Velzen CL, Haak MC, Reijnders G, Rijlaarsdam ME, Bax CJ, Pajkrt E, Hruda J, Galindo-Garre F, Bilardo CM, de Groot CJ, Blom NA, Clur SA. Prenatal detection of transposition of the great arteries reduces mortality and morbidity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:320–325. doi: 10.1002/uog.14689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kipps AK, Feuille C, Azakie A, Hoffman JI, Tabbutt S, Brook MM, Moon-Grady AJ. Prenatal diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome in current era. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahle WT, Clancy RR, McGaurn SP, Goin JE, Clark BJ. Impact of prenatal diagnosis on survival and early neurologic morbidity in neonates with the hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1277–1282. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.