Abstract

Objective

While traumatic brain injury (TBI) is common across the lifespan, the detailed neurobehavioral characteristics of older adults with prior TBI remain unclear. Our goal was to compare the clinical profile of older independently-living veterans with and without prior TBI.

Setting

Two veterans' retirement communities

Participants

75 participants with TBI and 71 without (mean age 78 years)

Design

Cross-sectional

Main Measures

TBI history was determined by the Ohio State University TBI Questionnaire. We assessed psychiatric and medical history via interviews and chart review and conducted measures assessing functional/lifestyle, psychiatric, and cognitive outcomes. Regression analyses (adjusted for demographics, diabetes, prior depression, substance abuse, and site) were performed to compare between TBI and non-TBI participants.

Results

Compared to veterans without TBI, those with TBI had greater functional impairment (adjusted p = 0.05), endorsed more current depressive (adjusted p=0.04) and PTSD symptoms (adjusted p=0.01), and had higher rates of prior depression and substance abuse (both adjusted p<0.01). While composite memory and language scores did not differ between groups, participants with TBI performed worse on tests of executive functioning/processing speed (adjusted p=0.01).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that TBI may have adverse long-term neurobehavioral consequences and that TBI-exposed adults may require careful screening and follow-up.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with known short-term functional, psychiatric, and cognitive impairments.1,2 One of the most feared long-term consequences of moderate to severe TBI is cognitive impairment and dementia, with many studies reporting a two to three times increased risk of dementia associated with prior TBI.3-5 The specific profile of long-term neurobehavioral sequelae of TBI among TBI-exposed older adults, however, is not well-characterized. While studies linking TBI to dementia have suggested that the phenotype of post-TBI dementia may be similar to Alzheimer disease (AD)4,5 or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE),6 few studies have explored detailed characteristics among non-demented TBI-exposed elders, at a time when early symptoms may point to etiology.

Better understanding of the long-term outcomes of TBI is an important preliminary step in exploring the underlying etiology, mechanisms, and ultimately treatment and prevention of post-TBI impairments. It is especially important to understand the potential outcomes of TBI in high-risk populations, such as military veterans. Military veterans are at elevated risk of experiencing TBI compared to the civilian population, a risk which is not limited to those exposed to combat.7 Studies from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan estimate that 15-20% of deployed service members suffered at least one mild TBI (mTBI)8,9 and multiple mTBIs are common.10 Retrospective studies from the Vietnam era indicate that exposure to mTBI in that conflict was comparable to what is reported in more recent conflicts.11 Among civilians, an estimated 1.7 million Americans suffer TBI each year12 and the lifetime prevalence of TBI has been estimated to be greater than 40%.13 Thus, due to combined combat, non-combat military, and civilian exposure, a history of TBI is highly prevalent among older veterans.14

Our objectives were to (1) describe the characteristics of head injuries in older veterans, and (2) describe the neurobehavioral phenotype of older independently-living veterans with and without past TBI.

Methods

Study population

All participants were independently-living residents of the Armed Forces Retirement Home (Washington, D.C.) or the Veterans Home of California-Yountville (Yountville, CA), aged 50-95. Requirements for living in the independent housing section included the ability to independently perform activities of daily living (i.e., manage medications, appointments, laundry, etc.), live in a communal environment, and the absence of active substance abuse. We excluded individuals with low cognition [Mini-Mental State Examination15 (MMSE) < 20], anyone with a past penetrating head injury, and those with medical conditions, hearing loss, or vision loss severe enough to preclude participating in the majority of study components. Residents were recruited through the use of flyers, town hall meetings, and word of mouth. The study was approved by the Human Research Committees at each site. All participants gave written informed consent.

Assessment of TBI history

A positive TBI history was defined as having sustained at least one prior head injury necessitating medical care (doctor's visit, emergency room, treatment from field medic, hospitalization, etc.). Detailed TBI history was evaluated using the Ohio State University TBI Identification Method (OSU-TBI ID)16, a structured clinical interview. From this, we determined the severity of all TBIs over the life course, the number of total TBIs for each participant, the cause of each TBI, and the age at each TBI. Although medical record verification of all TBI cases at time of injury was not feasible, we reviewed the participants' retirement home chart and validated TBI history in 51% of the TBI participants and absence of TBI history in the non-TBI participants.

The TBI was categorized as mild17: no loss of consciousness (LOC) or LOC < 30 minutes; moderate: LOC ≥ 30 minutes but < 24 hour; or severe: LOC ≥ 24 hours. Each head injury was described as military or civilian. Military TBI encompassed injuries occurring during combat or non-combat duty activities while the participant was in the military. Civilian TBI was defined as occurring before or after military service.

Assessment of past medical and psychiatric history

A medical history was compiled for each participant through a combination of chart review and self-report to assess past and current medical conditions. Psychiatric history, consisting of depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders other than PTSD (such as generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder), and substance abuse (alcohol or other drugs), was assessed in a similar manner.

Lifestyle, Functional, and Psychiatric Outcomes

Several well-validated and reliable instruments were used to assess lifestyle, functional, and psychiatric outcomes among participants. To evaluate sleep quality, we used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index18 (PSQI), a brief questionnaire assessing sleep habits in the past month. We used the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale19 (SWLS) to assess quality of life. To examine leisure activity level (how often participants read a book, went to group discussions, attended a concert, etc.), we used the Intellectual and Leisure Activity Scale (ILAS)20. We assessed function with the Functional Activities Questionnaire21 (FAQ) and the Everyday Cognition scale-short form22 (ECOG), both self-report. Current depressive symptoms were measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale23, a 15-item scale which surveys symptoms during the past week. PTSD symptoms were assessed by participant responses to the PTSD Checklist-Civilian (PCL-C)24, a 17-item instrument to measure PTSD symptoms in the past 30 days.

Cognitive Outcomes

A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered to each participant by a trained examiner. Included was the Mini-Mental State Examination15 (MMSE), a measure of general cognition. Specific domains assessed included learning and memory (Auditory Verbal Learning Task; AVLT; 25,26 sum of five learning trials and delayed recall), language (Boston Naming Test-Short Form; BNT27 and Category Verbal Fluency28,29), and processing speed/executive functioning (Trail Making Tests A and B30 and Digit Symbol31). Z-scores for the individual test variables were created using the mean and standard deviation from the non-TBI group. Composite variables were created by combining the z-scores from the individual test variables in each cognitive domain.

Statistical analyses

We compared demographics and past medical/psychiatric history between TBI and non-TBI participants using t-tests or chi-square tests as appropriate for continuous or categorical variables. We compared lifestyle, functional, psychiatric, and cognitive outcomes between groups using regression models as appropriate for continuous or categorical measures. We adjusted for demographics and medical comorbidities that significantly differed (p < 0.05) by TBI group (age, race, and history of diabetes) and also adjusted for gender, education, and site. All analyses of non-psychiatric outcomes were also adjusted for psychiatric history that significantly differed (p < 0.05) by group (history of depression and substance abuse). In sensitivity analyses of cognitive outcomes, the analyses were additionally adjusted for current depression and PTSD symptoms as objectively measured by the GDS and PCL-C. Lastly, to determine the role of TBI severity and frequency, we used trend analysis to compare outcomes between non-TBI, mild TBI, and moderate-to-severe TBI as well as between non-TBI, single TBI, and multiple TBI participants. Unadjusted frequencies and means are shown in all tables. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2.

Results

We enrolled 75 participants with a history of TBI and 71 participants with no history of TBI. Most TBI participants (61%) experienced more than one TBI in their lifetime, and most (72%) reported loss of consciousness for at least one TBI (Table 1). First TBI occurred an average of 50 (standard deviation 22) years previously and most recent TBI occurred an average of 32 (standard deviation 25) years previously. Thus, most TBIs were very remote. In total, 159 symptomatic head injuries were recorded for these 75 participants. Falls (35%) and blunt force trauma (34%) were the most common causes of TBI, followed by motor vehicle or bicycle accidents, blast injuries, and other (Table 1). Because most TBI participants experienced multiple prior TBIs, TBI severity for each participant was categorized based on each participant's most severe prior TBI. Overall, 68% of TBI participants were categorized as mild, 20% as moderate, and 12% as severe.

Table 1. Characteristics of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) among the 75 veterans with history of TBI.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age at first TBI, years | 26.9 (21.5) |

| Age at most recent TBI, years | 44.4 (24.8) |

| Participants with > 1 TBI | 61.3% |

| At least 1 TBI with LOC | 72.0% |

| Military related TBI | 28.0% |

| Mechanism of injury (all TBIs) | |

| Falls | 34.6% |

| Blunt Force Trauma | 34.0% |

| Motor Vehicle or Bicycle Accident | 24.5% |

| Blast Injuries | 5.0% |

| Other | 1.9% |

| Severity (most severe per person) | |

| Mild | 68% |

| Moderate | 20% |

| Severe | 12% |

LOC = loss of consciousness

Basic demographic, medical, and psychiatric history comparisons between veterans with and without TBI are shown in Table 2. Compared to veterans without a TBI, TBI participants were less likely to be a minority (p=0.01), more likely to have a history of diabetes (p < 0.01), more commonly reported a prior history of depression and substance abuse (both p < 0.01), and trended to being younger (p = 0.06). No significant differences between groups were found for history of anxiety, PTSD, or bipolar disorder.

Table 2. Demographics and Medical/Psychiatric History of the veterans by TBI history.

| Mean (SD) or % | Non-TBI N = 71 |

TBI N = 75 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 78.9 (8.8) | 76.5 (10.2) | 0.06 |

| Male | 88.7% | 92.0% | 0.27 |

| Non-white race | 12.7% | 2.7% | 0.01 |

| Education, years | 14.6 (2.7) | 14.3 (2.6) | 0.26 |

| Military Service, years | 10.9 (8.9) | 11.1 (8.9) | 0.44 |

| Past Medical History | |||

| Hypertension | 78.9% | 77.0% | 0.40 |

| Stroke | 12.7% | 13.5% | 0.44 |

| Diabetes | 18.3% | 38.7% | <0.01 |

| Past Psychiatric History | |||

| Depression | 18.3% | 44.0% | <0.01 |

| Anxiety | 15.7% | 26.7% | 0.29 |

| PTSD | 8.5% | 17.6% | 0.10 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 4.2% | 8.0% | 0.40 |

| Substance abuse | 20.0% | 46.7% | <0.01 |

PTSD=Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Lifestyle and Functional Outcomes

TBI participants reported worse sleep quality, lower participation in intellectual/leisure activities, more functional impairment (FAQ), worse cognitively-mediated functional impairment (eCog), and lower satisfaction with life compared to non-TBI participants (all effects were significant at least at the trend level with P < 0.10, see Table 3). After adjustment for covariates, functional impairment remained greater among TBI participants (FAQ p = 0.06, eCog p = 0.05).

Table 3. Clinical profile of older veterans with and without prior TBI.

| Mean (SD) or % | Non-TBI N = 71 |

TBI N = 75 |

Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle/Functional | ||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory† | 6.7 (5.2) | 8.4 (5.4) | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Intellectual/Leisure Activities Scale | 29.4 (8.5) | 25.4 (9.6) | <0.01 | 0.23 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire† | 0.48 (1.7) | 1.3 (3.7) | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| Everyday Cognition† | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | 28.0 (5.7) | 25.5 (6.4) | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| Psychiatric | ||||

| Geriatric Depression Scale† | 1.1 (1.6) | 2.0 (2.8) | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian† | 19.5 (6.6) | 23.1 (8.5) | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Cognitive | ||||

| Mini Mental Status Examination | 28.2 (1.5) | 27.5 (2.6) | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Learning/memory Z-score | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| Language Z-score | 0.0 (0.9) | -0.1 (0.9) | 0.64 | 0.71 |

| Executive function/processing speed Z-score | 0.0 (0.8) | -0.3 (1.1) | 0.04 | 0.01 |

adjusted for age, gender, race, education, history of diabetes, and site (all non-psychiatric outcomes also adjusted for history of depression and prior substance abuse).

higher score is worse

With increasing TBI severity, participants reported increasing impairments across most lifestyle and functional outcomes (Table 4). Similar results were found for increasing TBI frequency (data not shown). After multivariable adjustment, functional impairment remained worse and satisfaction with life remained progressively lower with increasing TBI severity (adjusted p-value for trend FAQ p = 0.03, eCOG p = 0.04, SWLS p = 0.06). Similarly, after multivariable adjustment cognitively-mediated functional impairment remained worse with increasing TBI frequency (adjusted p-value for trend eCog p = 0.04).

Table 4. Clinical profile of older veterans according to TBI severity.

| Mean (SD) or % | Non-TBI N = 71 |

Mild TBI N = 51 |

Mod/Sev TBI N = 24 |

Unadjusted p-value for trend | Adjusted p-value for trend* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle/Functional | |||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory† | 6.7 (5.2) | 7.5 (5.2) | 10.3 (5.5) | <0.01 | 0.14 |

| Intellectual/Leisure Activities Scale | 29.4 (8.5) | 25.7 (9.9) | 24.6 (9.0) | 0.01 | 0.21 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire† | 0.5 (1.7) | 1.0 (2.2) | 2.0 (5.7) | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Everyday Cognition† | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | 28.0 (5.7) | 26.7 (6.4) | 22.8 (5.8) | <0.01 | 0.06 |

| Psychiatric | |||||

| Geriatric Depression Scale† | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.9 (2.8) | 2.2 (3.0) | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian† | 19.5 (6.6) | 22.1 (7.7) | 25.2 (10.0) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cognitive | |||||

| MMSE | 28.2 (1.5) | 27.3 (2.8) | 27.8 (2.0) | 0.18 | 0.34 |

| Learning/memory Z-score | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.1 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| Language Z-score | 0.0 (0.9) | -0.1 (0.9) | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| Executive function/processing speed Z-score | 0.0 (0.8) | -0.3 (1.2) | -0.4 (1.1) | 0.04 | 0.01 |

adjusted for age, gender, race, education, history of diabetes, and site (all non-psychiatric outcomes also adjusted for history of depression and prior substance abuse).

higher score is worse

Psychiatric Outcomes

Compared to participants without TBI, TBI participants reported nearly two times higher scores on the GDS and 18% higher scores on the PCL-C (all effects were significant at P < 0.05 both before and after multivariable adjustment, see Table 3). Symptoms of depression and PTSD as measured by the GDS and PCL-C, respectively, also increased with increasing TBI severity (Table 4) and increasing TBI frequency, a finding that remained significant both before and after multivariable adjustment.

Cognitive Outcomes

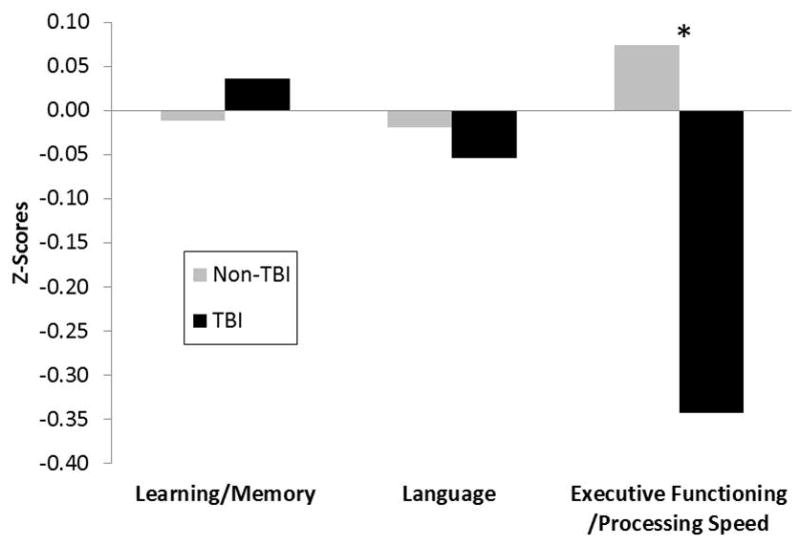

Global cognition (MMSE) was slightly lower among TBI participants compared to non-TBI participants (unadjusted p=0.05), but this finding was no longer significant with covariate adjustment and also did not differ by TBI severity or frequency. There were no differences between groups in performance on the cognitive domains of learning/memory or language (P > 0.6 for all). In the domain of executive functioning / processing speed, however, TBI participants performed worse than non-TBI participants, an effect that remained significant both before and after adjustment for covariates. Furthermore, those with greater TBI severity and TBI frequency had worse scores in this domain both before and after adjustment for covariates.

In a sensitivity analysis designed to account for possible adverse cognitive effects of ongoing depressive or PTSD symptoms, we further adjusted cognitive outcome analyses for score on GDS and PCL-C. Executive functioning / processing speed remained significantly more impaired among TBI participants (see adjusted means in Figure) and with increasing TBI severity/frequency.

Figure. Sensitivity analysis of cognitive domains accounting for psychiatric symptoms among veterans with and without TBI.

Legend: After multivariable adjustment including adjustment for current psychiatric symptoms, older veterans with TBI had significantly greater impairments in executive functioning/processing speed compared to veterans without TBI. The mean z-scores shown in the figure reflect the adjusted means and therefore the “Non-TBI” mean z-scores are not equal to zero.; * P = 0.02 adjusted for age, gender, race, education, diabetes, history of depression, prior substance abuse, site, Geriatric Depression Scale score, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist - Civilian score.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that older veterans with a past history of TBI, but who are living independently in retirement communities, demonstrate worse functioning in multiple clinical domains compared to their peers without prior TBI. Specifically, TBI participants had more impaired scores on most lifestyle, functional, and psychiatric outcomes assessed as well as on tests of global cognition and executive function/processing speed. Even after adjustment for demographics and medical/psychiatric history, TBI participants were still found to be significantly more impaired than their non-TBI peers on measures of function, symptoms of depression and PTSD, and tests of executive function/processing speed, suggesting that many of these clinical differences are not explained by differences in demographics or comorbidities. Furthermore, many of these impairments in function, psychiatric symptoms, and executive function/processing speed deficits increased with increasing TBI severity and increasing TBI frequency, providing additional support for a causal association. Because active psychiatric symptoms may confound cognitive impairment, we performed sensitivity analyses of cognitive outcomes additionally adjusted for current symptoms of depression and PTSD and found that TBI participants have more impaired executive function/processing speed that appears to be independent of psychiatric symptoms.

Our results build upon the findings of prior studies that have examined chronic effects of TBI. The term “chronic” or “long-term” in the field of TBI research, however, is frequently used to refer to effects measured just a few months or years post-TBI.32 Most prior studies of “chronic” effects of TBI have largely followed outcomes at most 10 to 15 years post-TBI,33-35 have predominantly assessed outcomes among adolescents or young to middle-aged adults,32,33,36 have frequently not included a comparison group without TBI,33,37 and may rely upon mailed surveys rather than in-person evaluations.36-38 Thus, the effects of remote TBI into late-life, particularly as compared to normal aging, have not been rigorously studied. Our findings highlight that TBI may have important long-term effects on aging and suggests that TBI-exposed elders need to be monitored closely for neurobehavioral symptoms.

While previous research has consistently shown adverse long-term effects of moderate-to-severe TBI, the long-term effects of mild TBI have been mixed39-42. A recent systematic review of mild TBI reported that in well-controlled studies, mild TBI was not associated with long-term cognitive or psychiatric outcomes43. In the current study, the majority (68%) of our participants with TBI had mild TBI as their most severe head injury, yet we found differences in lifestyle and functional outcomes, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive performance. We further examined the influence of TBI severity and frequency on our outcomes and found that most of our outcomes were associated with greater severity and frequency of TBI. However, as only 15 of the 75 participants with TBI had a single mild TBI, the results were likely driven by individuals with repeated mild TBI and moderate-to-severe TBI.

The observed phenotype of executive dysfunction, behavioral symptoms, and functional impairment has been reported in younger patients or those with more recent TBI. For example, among primarily young to middle-aged adults with TBI an average of 15 years previously, increasing TBI severity or TBI frequency has been associated with greater cognitive impairment/complaints, impaired social activity/behavior, and greater functional impairment.33,36 Similarly, individuals across the age spectrum with follow-up five to 10 years after TBI have been found to have more cognitive difficulties, more anxiety, more PTSD, and worse function compared to controls.34 Young American military veterans an average of three months post-TBI have been found to have worse performance specifically on executive function and processing speed compared to healthy controls,32 similar to our own results. One central question that emerges from this literature is whether these deficits are static or progressive. A Swiss study that compared self-reported outcomes one year after TBI to outcomes 10 years after TBI found that many with TBI experienced progressive decline in quality of life, increasing cognitive complaints, and increasing rates of disability/unemployment, suggesting that some chronic post-TBI deficits may be progressive over time.35

Our findings suggest that the clinical phenotype of older veterans with remote TBI is not an amnestic pattern, which might be expected to precede a clinical diagnosis of late-onset amnestic mild cognitive impairment or typical late-onset Alzheimer's dementia. Rather, the phenotype we have identified – with symptoms of depression/PTSD and executive function/processing speed cognitive impairments – bears similarities to the mood/behavior phenotype that has been described in autopsy-confirmed cases of CTE6 and in the behavioral/dysexecutive variant of Alzheimer's dementia.44 As mentioned above, it is unclear from this cross-sectional study, however, whether the phenotype we identified reflects primarily static residual deficits of prior TBI or the early stage of a progressive, potentially degenerative, process. Ultimately, understanding the pathophysiology of TBI-associated neurobehavioral disorders will require studies that incorporate imaging, cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers, and pathology.

Strengths of this study include that each participant underwent a highly detailed multi-domain in-person evaluation. Other strengths of this study include the use of the OHSU-TBI ID, a validated TBI screening instrument that is one of the TBI common data elements recommended by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, as well as corroboration of TBI history via chart review whenever possible. Our findings are also strengthened by the inclusion of a comparison cohort that is similar to the TBI participants, and who were actually living side-by-side in the same military retirement communities. Lastly, the study is strengthened by the lack of overly restrictive exclusionary criteria, thus making this study highly representative of the aging veteran population, among whom multiple medical comorbidities are common.

Some aspects of our study need to be considered when interpreting our results. Although we used a highly-regarded clinical interview to determine TBI history, in many individuals TBI history was self-report only, as medical records were not available. This may have led to inaccurate reporting of these often very remote TBIs. The cross-sectional design limits our ability to determine if these deficits are chronic or progressive. In addition, veterans with more impairment may be less likely to participate in the study. A final limitation is the predominantly white and male study population, which was highly representative of the veteran population residing in the study sites, but not of the general veteran or civilian population. This limitation may serve to under-estimate the degree of post-TBI impairment in the veteran population as racial and ethnic minorities may have worse functional outcomes following TBI.45

Given the aging of the global population in combination with the high lifetime prevalence and declining mortality of TBI, the elderly TBI population is rapidly growing. This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of what specific deficits may be present among older independently-living veterans an average of 30 years following TBI of varied severities and frequencies. Given our focus in this study on independently-living veterans, who likely represent the healthier end of the aging veteran population, as well as our adjustment for multiple covariates, it is even more notable that we identified so many domains of significant impairment among the TBI participants. These surprising results underscore the critical need for ongoing efforts at developing improved rehabilitation strategies for the very chronic effects of TBI as well as the need to further elucidate underlying mechanisms and ultimately treatments of these chronic effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our research participants, the Armed Forces Retirement Home in Washington, D.C., the Veterans Home of California in Yountville, CA, and our dedicated study staff including Kim Kelley, Ross Passo, and Leah Harburg. This project was supported by the Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0581). RCG receives support from the NINDS (K23 NS095755), the American Federation for Aging Research, and the UCSF Pepper Center. KK and RD-A receive support from the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine and the Military Clinical Neurosciences Center of Excellence. KY receives support from the Department of Defense and VA (W81XWH-12-PHTBI-CENC, W81XHW-14-2-0137) and NIA (K24 AG031155).

Source of Funding: This study is supported by the Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0581).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest :The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Taylor CA, Jung HY. Disorders of Mood After Traumatic Brain Injury. Seminars in clinical neuropsychiatry. 1998 Jul;3(3):224–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dikmen S, McLean A, Jr, Temkin NR, Wyler AR. Neuropsychologic outcome at one-month postinjury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1986 Aug;67(8):507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, et al. Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2000 Oct 24;55(8):1158–1166. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Z, Cupples LA, Kurz A, et al. Head injury and the risk of AD in the MIRAGE study. Neurology. 2000 Mar 28;54(6):1316–1323. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleminger S, Oliver DL, Lovestone S, Rabe-Hesketh S, Giora A. Head injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: the evidence 10 years on; a partial replication. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 Jul;74(7):857–862. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, et al. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology. 2013 Sep 24;81(13):1122–1129. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okie S. Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 19;352(20):2043–2047. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 31;358(5):453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanielian TL, Jaycox LH. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Vol. 720. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruff RL, Riechers RG, 2nd, Wang XF, Piero T, Ruff SS. A case-control study examining whether neurological deficits and PTSD in combat veterans are related to episodes of mild TBI. BMJ open. 2012;2(2):e000312. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trudeau DL, Anderson J, Hansen LM, et al. Findings of mild traumatic brain injury in combat veterans with PTSD and a history of blast concussion. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 1998 Summer;10(3):308–313. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado V, Dellinger AM. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: National Estimates of Prevalence and Incidence, 2002-2006. Injury Prev. 2010 Sep;16:A268–A268. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiteneck GG, Cuthbert JP, Corrigan JD, Bogner JA. Prevalence of Self-Reported Lifetime History of Traumatic Brain Injury and Associated Disability: A Statewide Population-Based Survey. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2015 Apr 29; doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Culver C, Diaz-Arrastia R, McCormack M, Awoke S, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury and comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms in an older veteran population. Paper presented at: Alzeimer's Association International Conference2013; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan JD, Bogner J. Initial reliability and validity of the Ohio State University TBI Identification Method. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2007 Nov-Dec;22(6):318–329. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300227.67748.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/mTBI. 2009 Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/concussion_mtbi_full_1_0.pdf.

- 18.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989 May;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of personality assessment. 1985 Feb;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Miles T, et al. The association of race and socioeconomic status with cardiovascular disease indicators among older adults in the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002 Jul;57(4):S247–256. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.s247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982 May;37(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomaszewski Farias S, Mungas D, Harvey DJ, Simmons A, Reed BR, Decarli C. The measurement of everyday cognition: development and validation of a short form of the Everyday Cognition scales. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 Nov;7(6):593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacology bulletin. 1988;24(4):709–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL–C) 1991 Available from F. W. Weathers, National Center for PTSD, Boston Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 150 S. Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02130. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rey A. L'examen clinique en psychologie. Paris, France: Presses, Universitaires de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor EM. Psychological appraisal of children with cerebral deficits. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan EF, Goodglas H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Boston: Kaplan & Goodglass; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 3rd. Iowa City, IA: AJA Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris JC, Mohs R, Rogers H, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's Disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:641–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (DK-EFS) San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation, a Harcourt Assessment Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation - Harcourt Brace & Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robb Swan A, Nichols S, Drake A, et al. Magnetoencephalography Slow-Wave Detection in Patients with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Ongoing Symptoms Correlated with Long-Term Neuropsychological Outcome. Journal of neurotrauma. 2015 Jun 18; doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rassovsky Y, Levi Y, Agranov E, Sela-Kaufman M, Sverdlik A, Vakil E. Predicting long-term outcome following traumatic brain injury (TBI) Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2015;37(4):354–366. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2015.1015498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahm J, Ponsford J. Comparison of long-term outcomes following traumatic injury: what is the unique experience for those with brain injury compared with orthopaedic injury? Injury. 2015 Jan;46(1):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zumstein MA, Moser M, Mottini M, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: a prospective observational study. The Journal of trauma. 2011 Jul;71(1):120–127. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f2d670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halldorsson JG, Arnkelsson GB, Tomasson K, Flekkoy KM, Magnadottir HB, Arnarson EO. Long-term outcome of medically confirmed and self-reported early traumatic brain injury in two nationwide samples. Brain injury : [BI] 2013;27(10):1106–1118. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.765599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown AW, Moessner AM, Mandrekar J, Diehl NN, Leibson CL, Malec JF. A survey of very-long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury among members of a population-based incident cohort. Journal of neurotrauma. 2011 Feb;28(2):167–176. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Harding HP, Jr, Guskiewicz KM. Nine-year risk of depression diagnosis increases with increasing self-reported concussions in retired professional football players. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012 Oct;40(10):2206–2212. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanderploeg RD, Curtiss G, Belanger HG. Long-term neuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005 May;11(3):228–236. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanderploeg RD, Curtiss G, Luis CA, Salazar AM. Long-term morbidities following self-reported mild traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007 Aug;29(6):585–598. doi: 10.1080/13803390600826587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vasterling JJ, Brailey K, Proctor SP, Kane R, Heeren T, Franz M. Neuropsychological outcomes of mild traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in Iraq-deployed US Army soldiers. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Sep;201(3):186–192. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ponsford J, Cameron P, Fitzgerald M, Grant M, Mikocka-Walus A. Long-term outcomes after uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injury: a comparison with trauma controls. Journal of neurotrauma. 2011 Jun;28(6):937–946. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cancelliere C, et al. Systematic review of the prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury in adults: cognitive, psychiatric, and mortality outcomes: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2014 Mar;95(3 Suppl):S152–173. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ossenkoppele R, Pijnenburg YA, Perry DC, et al. The behavioural/dysexecutive variant of Alzheimer's disease: clinical, neuroimaging and pathological features. Brain. 2015 Jul 2; doi: 10.1093/brain/awv191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St audenmayer KL, Diaz-Arrastia R, de Oliveira A, Gentilello LM, Shafi S. Ethnic disparities in long-term functional outcomes after traumatic brain injury. The Journal of trauma. 2007 Dec;63(6):1364–1369. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815b897b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]