Abstract

Pseudogenes are generally considered to be non-functional DNA sequences that arise from protein-coding genes through nonsense or frame-shift mutations1. Although certain pseudogene-derived RNAs have regulatory roles2, and some pseudogene fragments are translated3, no clear functions for pseudogene-derived proteins are known. Olfactory receptor families contain many pseudogenes, reflecting low selection pressures to maintain receptors that are either functionally redundant or detect odours no longer relevant for a species’ fitness4. Here we have characterised a pseudogene in the chemosensory variant ionotropic glutamate receptor (IR) repertoire5,6 of Drosophila sechellia, an insect endemic to the Seychelles that feeds only on ripe fruit of Morinda citrifolia7. This locus, DsecIr75a, bears a premature termination codon (PTC) that appears to be fixed in the population. Unexpectedly, DsecIr75a encodes a functional receptor, due to efficient translational readthrough of the PTC. Readthrough occurs only in neurons, and is independent of the type of termination codon but dependent upon the sequence downstream of the PTC. Furthermore, while the intact D. melanogaster IR75a orthologue detects acetic acid – a chemical cue important for this species to locate fermenting food8,9 but at trace levels in Morinda fruit10 – DsecIR75a has evolved distinct odour-tuning properties, through amino acid changes in its ligand-binding domain. We identify functional PTC-containing loci within different olfactory receptor repertoires and species, suggesting that such “pseudo-pseudogenes” represent a widespread phenomenon.

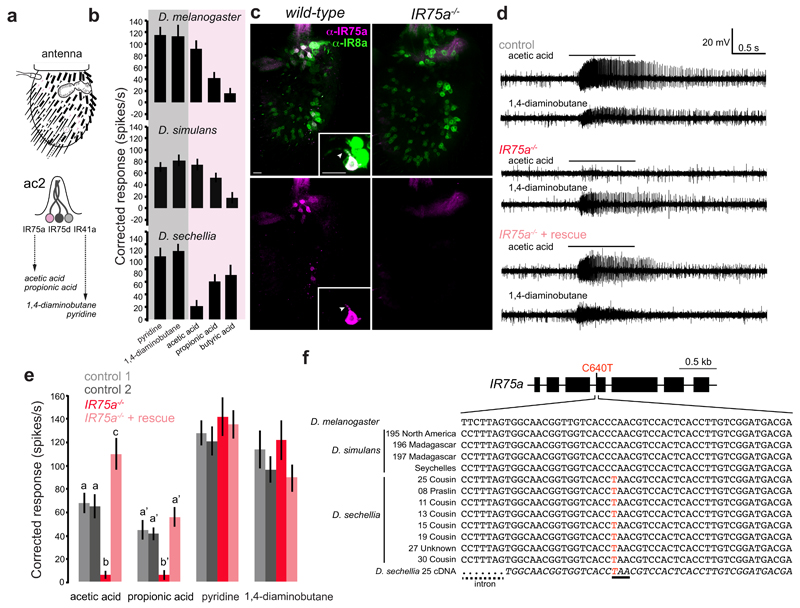

Comparative electrophysiological analysis in closely-related drosophilid species of olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) responses revealed a loss of sensitivity to acetic acid in D. sechellia neurons housed in the antennal coeloconic 2 (ac2) sensillum class of sensory hairs (Fig. 1a-b). In D. melanogaster, acetic acid is detected by ac2 OSNs expressing IR75a11; these sensilla house two other neurons that are sensitive to amines and express IR41a and IR75d11,12 (Fig. 1a). Two lines of evidence support IR75a as the acetic acid receptor. First, the protein is expressed exclusively in these acetic acid-sensing ac2 neurons, where it co-localises with the IR co-receptor IR8a13 in somata and sensory dendrites (Fig. 1c). Second, protein null Ir75a mutant animals (Fig. 1c) lack responses to acetic acid (and other organic acids) in these sensilla, while amine ligand-evoked action potentials are unaffected (Fig. 1d-e). Acid sensitivity is restored by expression of an Ir75a cDNA in these neurons (Fig. 1d-e).

Fig. 1. Ir75a encodes an acetic acid receptor in D. melanogaster, and is a transcribed pseudogene in D. sechellia.

a, Top: schematic of the third antennal segment covered with porous olfactory sensilla of various morphological classes. Bottom: schematic of the ac2 sensillum class, which houses three olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) that express different Ir genes.

b, Electrophysiological responses in ac2 sensilla to the indicated odours (mean±SEM; mixed genders) in D. melanogaster30 (n=9), D. simulans31 (n=9) and D. sechellia31 (n=8). The shading on the histograms distinguishes two broad chemical classes of odours (magenta [acids], grey [amines]).

c, Immunostaining with ?anti-IR75a (magenta) and anti-IR8a (green) antibodies on antennae of wild-type (left) or Ir75a mutant (Ir75aMB00253, right) animals. The inset shows the colocalisation of IR75a and IR8a in the OSN soma and dendritic compartment (arrowhead). Scale bars = 10 μm.

d, Representative traces of extracellular recordings of neuronal responses to the indicated stimuli in ac2 sensilla in control (Ir75a-Gal4,Ir75aMB00253/+), Ir75a hemizygous mutant (Ir75aMB00253/Df(3L)BSC415) and Ir75a rescue (UAS-DmelIr75a;Ir75a-Gal4,Ir75aMB00253/Df(3L)BSC415) animals. Bars above the traces mark 1 s stimulus time.

e, Quantification of solvent-corrected responses in (d) (mean±SEM; mixed genders). Genotypes: control 1 (Df(3L)BSC415/+, n=12), control 2 (Ir75a-Gal4,Ir75aMB00253/+, n=11), Ir75a hemizygous mutant (Ir75a-Gal4,Ir75aMB00253/Df(3L)BSC415, n=12), Ir75a rescue (UAS-DmelIr75a;Ir75a-Gal4, Ir75aMB00253/Df(3L)BSC415, n=13). Bars labelled with different letters are significantly different (Source Data & Methods). For odours with unlabelled bars, no significant differences were found across genotypes.

f, Top: gene model of Ir75a indicating the position of the C640T nucleotide change in the D. sechellia orthologue. Bottom: Genomic sequence spanning this nucleotide position in D. melanogaster and several geographically-distributed D. simulans and D. sechellia strains (Methods). The bottom italicised sequence is of the D. sechellia cDNA. The D. sechellia C640T substitution (highlighted in red) creates a premature termination codon (underlined).

Ir75a orthologues are present across drosophilids6, but D. sechellia Ir75a (DsecIr75a) is a predicted pseudogene: a C640T nucleotide change in the ORF (compared to DmelIr75a) creates a premature termination codon (PTC) (CAA→TAA) in exon 4 (Fig. 1f), which would truncate the protein within the ligand-binding domain (LBD). The PTC is present in all D. sechellia strains we sequenced (from at least two islands of the Seychelles archipelago), but not in any D. melanogaster or D. simulans strain (Fig. 1f), suggesting is a derived change that is fixed in the D. sechellia population. We could, however, amplify Ir75a cDNA from D. sechellia antennal RNA; sequencing of this cDNA, as well as D. sechellia antennal RNA-sequencing data (Methods), verified that the PTC is not edited or spliced out of the transcript to maintain an intact ORF (Fig. 1f).

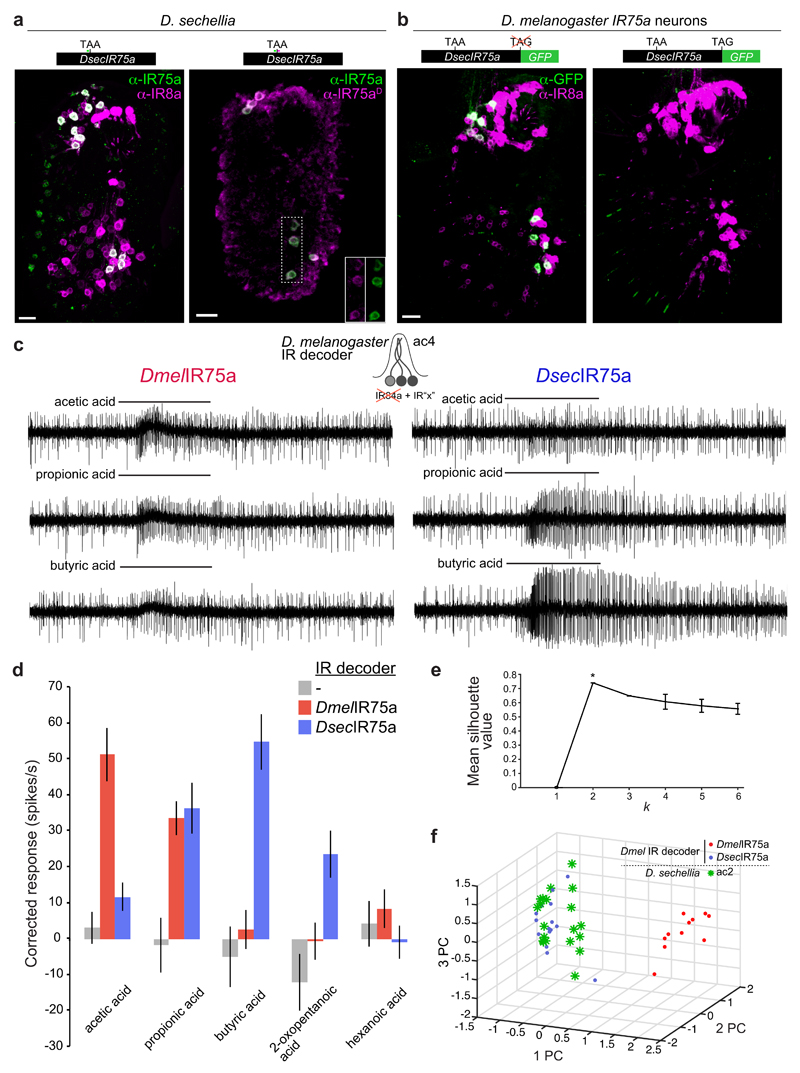

The pseudogenisation of DsecIr75a provided a logical explanation for the loss of responses to acetic acid in this species (Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, D. sechellia ac2 sensilla house a neuron that responds to other acidic odours (Fig. 1b), suggesting that another receptor is expressed in the OSNs “vacated” by mutation of Ir75a. However, we were unable to detect other acid-sensing IRs in these cells. We therefore wondered whether the Ir75a pseudogene might encode a functional receptor. Indeed, the IR75a antibody also stains OSNs in D. sechellia with an ac2-like distribution (Fig. 2a). Because its epitope is encoded upstream of the PTC, we generated a second antibody recognising sequence encoded downstream of the PTC (anti-IR75aD); this labelled the same cells (Fig. 2a). We also generated a transgene comprising DsecIr75a cDNA in which the terminal stop codon was removed and the coding sequence for GFP placed in-frame with the last coding codon (DsecIr75a:GFP). As D. sechellia is not yet amenable to transgenesis, we expressed this construct in D. melanogaster Ir75a neurons. GFP fluorescence was detected from DsecIR75a:GFP (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 1), indicating that the PTC is read through, permitting translation of the downstream GFP sequence. No GFP signal was observed with a control construct that retained the terminal stop codon (DsecIr75aSTOP:GFP) (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. Translational readthrough of the premature termination codon in D. sechellia Ir75a permits production of a functional olfactory receptor.

a, Immunofluorescence on D. sechellia antennae with anti-IR75a (green, recognising an epitope upstream of the PTC) and IR8a (magenta) (left) or anti-IR75a (green) and anti-IR75aD (magenta, recognising an epitope downstream of the PTC) (right). The insets show the separate channels for anti-IR75a and anti-IR75aD corresponding to the area demarcated with a dashed box. Scale bars = 10 µm.

b, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP antibodies (green) and anti-IR8a (magenta) on a D. melanogaster antenna in which Ir75a neurons express transgenes encoding DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/+;Ir75a-Gal4/+) (left) or DsecIR75aSTOP:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75aSTOP:GFP/+;Ir75a-Gal4/+) (right).

c, Representative traces of extracellular recordings of neuronal responses to the indicated stimuli in IR decoder neurons expressing DmelIR75a (UAS-DmelIr75a;Ir84aGal4) or DsecIR75a (UAS-DsecIr75a;Ir84aGal4).

d, Quantification of odour-evoked responses in empty IR decoder neurons (Ir84aGal4, n=5), or the decoder neurons expressing DmelIR75a (n=7-11) or DsecIR75a (n=7-14) (genotypes as in (c)) (mean±SEM; mixed genders).

e, k-means cluster analysis of the responses of DmelIR75a in the IR decoder, DsecIR75a in the IR decoder, and D. sechellia ac2 sensilla to the four main agonists (acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and 2-oxopentanoic acid). Mean silhouette value and standard deviation of all the solutions within each k value (n=100). The peak silhouette value at k = 2 was significantly different from other k values, indicating that responses of these three distinct neuron classes statistically fall within two clusters.

f, Plot of the three first principal components (PC) from a Principle Component Analysis of the same odour response profiles as in (e).

We next asked whether DsecIr75a encodes a functional receptor by mis-expressing it in heterologous “IR decoder” neurons (Methods). In these cells, DmelIR75a endowed sensitivity to acetic and propionic acids (Fig. 2c-d), consistent with endogenous acid responses of ac2 Ir75a OSNs (Fig. 1b). By contrast, DsecIR75a conferred responses to propionic, butyric and 2-oxopentanoic acids (Fig. 2c-d). Cluster analysis revealed that the responses of DsecIR75a in IR decoder neurons and the endogenous D. sechellia ac2 sensilla responses group together (Fig. 2e-f). These results provide evidence that the DsecIr75a pseudogene encodes a functional olfactory receptor underlying ac2 acid-sensing properties in D. sechellia.

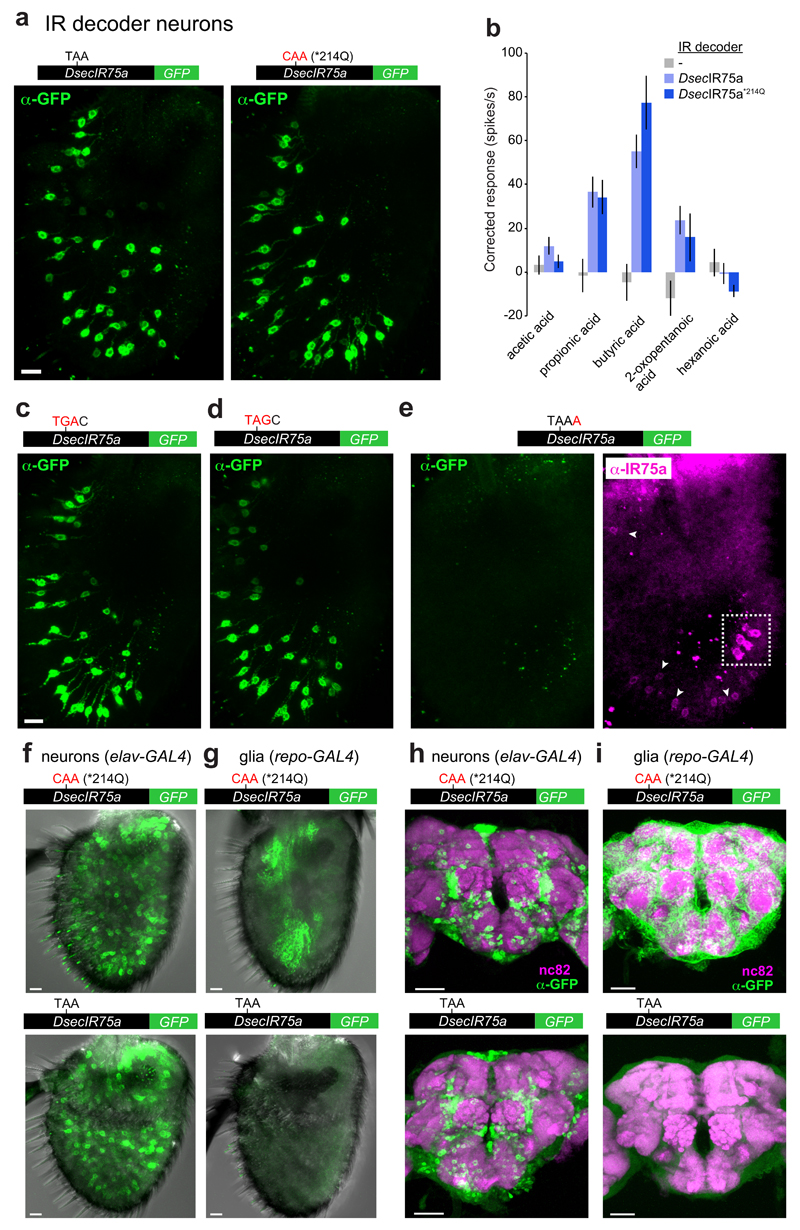

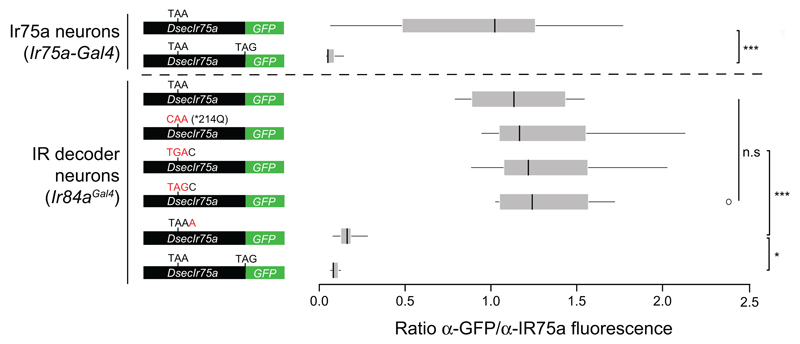

Reversion of the PTC to the ancestral glutamine-encoding codon (TAA→CAA; *214Q) in transgenic constructs had no effect on expression or function of DsecIR75a (Fig. 3a-b and Extended Data Fig. 1), implying that the PTC is readthrough efficiently and does not influence odour responses. Translational readthrough of terminal stop codons, resulting in C-terminal extensions, has been characterised for several eukaryotic genes14–16; in these cases, the “leakiness” of translation arrest is predicted to depend upon the termination codon (TGA>TAA>TAG) and the immediate 3’ nucleotide (C>T>G>A)14,15. We investigated the cis-regulatory elements determining the high efficiency of readthrough of the DsecIr75a PTC – which has the second most leaky termination codon context (TAAC) – by generating additional readthrough GFP reporters bearing mutations in this sequence (Fig. 3c-e). Replacement of the TAA PTC with either TGA or TAG did not affect GFP expression (Fig. 3c-d and Extended Data Fig. 1). By contrast, replacing the immediate 3’ C nucleotide with A almost completely blocked GFP expression (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 1). This transgene still produces a truncated protein, as detected by the IR75a antibody (Fig. 3e). These results indicate that sequence context outside, but not within, the DsecIr75a PTC is critical for determining readthrough efficiency.

Fig. 3. Efficiency and tissue-specificity of translational readthrough of the D. sechellia Ir75a PTC.

a, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP on D. melanogaster antennae in which IR84a neurons express transgenes encoding DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/+;Ir84aGal4/+) or DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/+;Ir84aGal4/+). Scale bar = 10 µm.

b, Quantification of odour-evoked responses in empty IR decoder neurons (Ir84aGal4, n=4-5), or those expressing DsecIR75a (UAS-DsecIr75a;Ir84aGal4), n=8-14) or DsecIR75a*214Q (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q;Ir84aGal4, n=8-11) (mean±SEM; mixed genders). No significant differences were found between the two genotypes in the responses to any of the odours (Student’s t-test).

c-e, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) on D. melanogaster antennae in which Ir84a neurons express DsecIr75a:GFP transgenes bearing the indicated mutations to the PTC or 3’ nucleotide (genotypes of the form: UAS-DsecIr75axxx:GFP/+;Ir84aGal4/+). In panel (e), immunofluorescence with anti-IR75a antibodies (magenta) is also shown, which reveals that this transgene encodes protein up to, but not beyond, the PTC i.e., signal is detected in Ir84a neurons with anti-IR75a (which detects an epitope upstream of the PTC) but not anti-GFP (arrowheads). The dashed white square indicates endogenous Ir75a neurons. Scale bar = 10 µm.

f, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) on D. melanogaster antennae in which elav-Gal4 drives neuronal expression of DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/elav-Gal4, 8/8 brain were GFP-positive) or DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/elav-Gal4, 5/5 GFP-positive). Scale bars = 10 µm.

g, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) on D. melanogaster antennae in which repo-Gal4 drives glial-specific expression of DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/repo-Gal4, 10/10 GFP-positive) or DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/repo-Gal4, 0/10 GFP-positive). Scale bars = 10 µm.

h, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) and synaptic neuropil marker nc82 (magenta) antibodies on D. melanogaster brains in which elav-Gal4 drives neuronal expression of DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/elav-Gal4, 6/6 GFP-positive) or DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/elav-Gal4, 8//8 GFP-positive). Scale bars = 50 µm.

i, Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) and nc82 (magenta) on D. melanogaster brains in which repo-Gal4 drives glial-specific expression of DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/repo-Gal4, 6/6 GFP-positive) or DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/repo-Gal4, 0/8 GFP-positive). Scale bars = 50 µm.

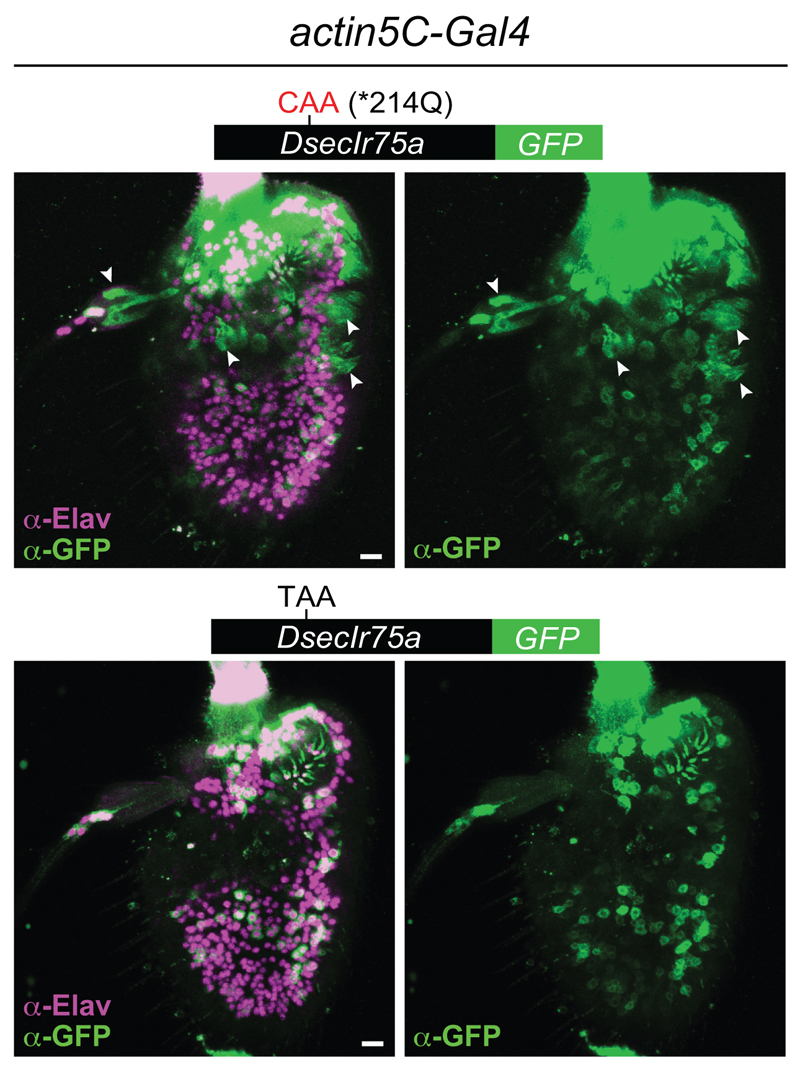

The encoding of full-length protein by PTC-containing DsecIr75a transgenes in two populations of D. melanogaster OSNs (i.e., Ir75a and IR decoder [Ir84a] neurons) indicates that the mechanisms that permit readthrough are not species- or OSN-class specific. We investigated whether readthrough occurs in other cell types by using an actin5C-Gal4 driver to broadly express DsecIr75a:GFP and, as control, DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP. DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP was detected in many but not all cells (Extended Data Fig. 2); this heterogeneity may arise from the variable expression of actin5C-Gal4. Nevertheless, the GFP-positive cells encompassed neurons and non-neuronal support cells (Extended Data Fig. 2, arrowheads). By contrast, DsecIR75a:GFP was detected exclusively in neurons (Extended Data Fig. 2). To confirm this finding, we compared expression of DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP and DsecIr75a:GFP transgenes induced by a pan-neuronal (elav-Gal4) or pan-glial (repo-Gal4) driver. Both transgenes produced similar GFP signals in sensory neurons throughout the antenna (Fig. 3f). However, only DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP was detectable in glia (Fig. 3g). Similarly, in the brains of these animals, we detected broad neuronal expression of both DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP and DsecIR75a:GFP (Fig. 3h), but glial expression for only DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (Fig. 3i). Thus, efficient readthrough of the DsecIr75a PTC occurs in diverse neuronal classes, but not in non-neuronal cells.

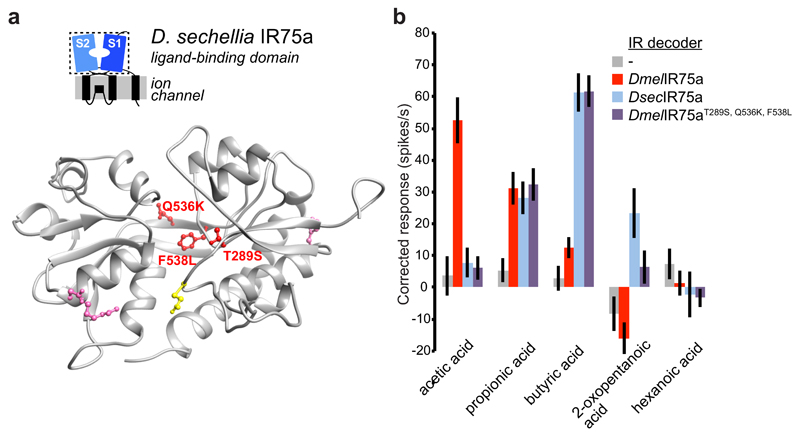

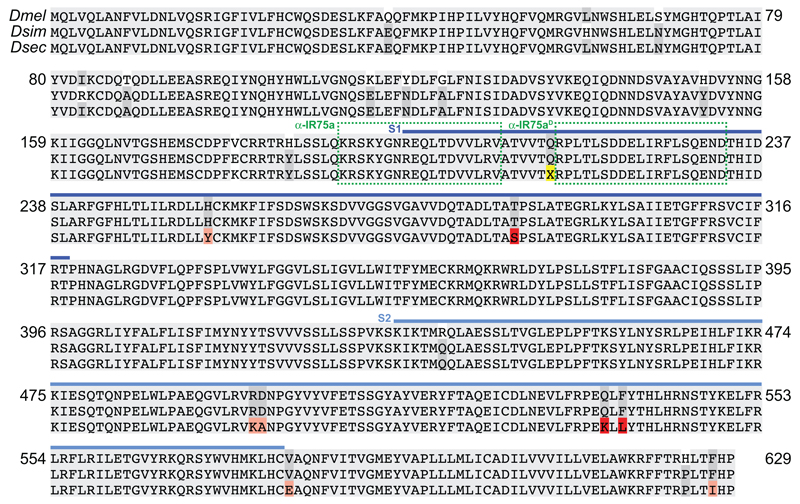

We next investigated the molecular basis of the different ligand-response profiles of DsecIR75a and DmelIR75a. As Ir75a neuron responses are conserved between D. melanogaster and D. simulans (Fig. 1b), we reasoned that ligand-specificity determinants would be conserved in IR75a sequences from these species but differ in DsecIR75a. Of eight such positions (excluding the PTC), six lie within the predicted bi-lobed LBD (Extended Data Fig. 3). On a protein homology model of the DsecIR75a LBD, three of these positions are located within the putative ligand-binding pocket (Fig. 4a). We tested their function by generating a version of DmelIr75a in which each of these positions was mutated to encode the amino acid present in DsecIR75a, and expressed this mutant (DmelIr75aT289S,Q536K,F538L) in IR decoder neurons. This engineered receptor conferred responses indistinguishable from those of DsecIR75a (Fig. 4b), indicating the importance of one or more of these residues as odour-specificity determinants.

Fig. 4. Molecular basis of the functional divergence of D. sechellia Ir75a.

a, Protein homology model of the LBD of DsecIR75a (Methods). The side chains of the residues that are different in D. sechellia IR75a compared with D. simulans and D. melanogaster IR75a are represented in pink, and the subset of these mutated in this study are shown in red. The location of the residue putatively encoded by the PTC is shown in yellow.

b, Quantification of odour-evoked responses in empty IR decoder neurons (Ir84aGal4, n=5-6) or the decoder neurons expressing DmelIR75a (n=9), DsecIR75a (n=8-9) or the DmelIR75aT289S,Q536K,F538L mutant (n=14) (genotypes: UAS-DxxxIr75axxx;Ir84aGal4) (mean±SEM;, mixed genders); experiments for all transgenes were performed in parallel. Responses to each odour of DsecIR75a and DmelIR75aT289S,Q536K,F538L are statistically indistinguishable (Wilcoxon sum-rank test).

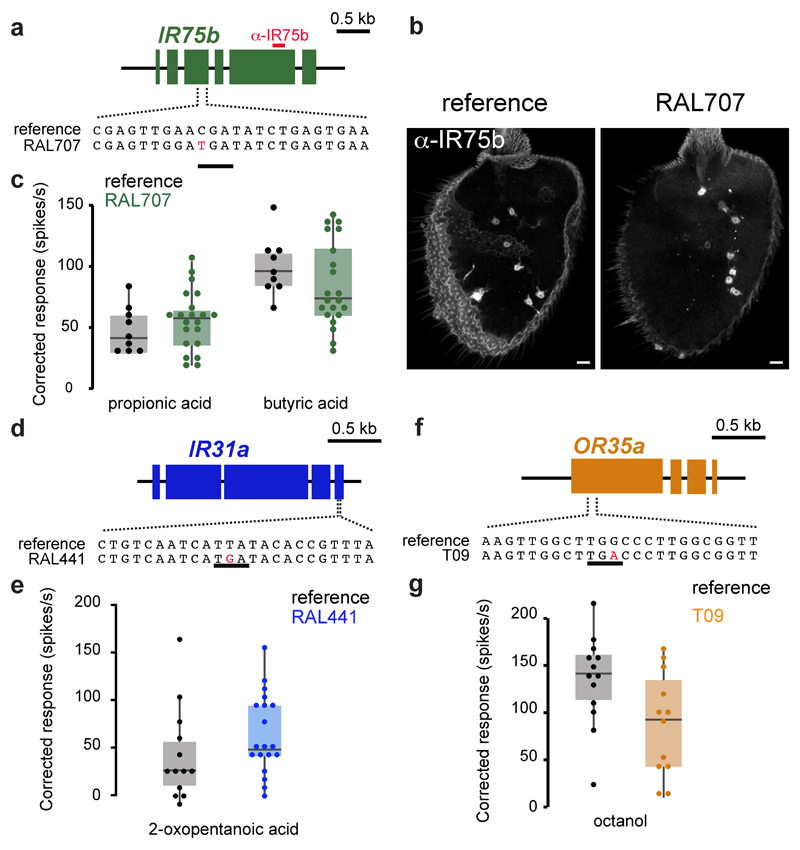

Finally, we sought other functional olfactory receptor pseudogenes. Within wild-caught isolates of D. melanogaster (Methods), we identified several strains in which the Ir75b ORF contains a C517T substitution creating a PTC (Fig. 5a and Methods). Immunostaining of antennae from flies of these lines with an IR75b antibody (recognising an epitope encoded downstream of the PTC) showed a pattern comparable to controls (Fig. 5a-b), indicating that this PTC is readthrough. Consistently, electrophysiological recordings in one of these lines (Raleigh707 [RAL707]) of Ir75b neurons presented with known agonists11 revealed robust responses (Fig. 5c). In another strain (RAL441) the Ir31a ORF contains a T1805G substitution, which is predicted to truncate the receptor before the third transmembrane domain (Fig. 5d). Nevertheless, electrophysiological recordings of RAL441 Ir31a neurons stimulated with 2-oxopentanoic acid11, revealed clear responses (Fig. 5e). We also identified a segregating PTC-containing allele of the odorant receptor (OR) gene Or35a (in Tasmanian strains T09 and T29) (Fig. 5f); in T09, responses of Or35a neurons to octanol12 were readily detected (Fig. 5g). These findings indicate the phenomenon of functional olfactory “pseudogenes” is restricted neither to a particular species nor a specific receptor repertoire.

Fig. 5. Functional “pseudogene” alleles of other receptors in other species.

a, Gene structure of D. melanogaster Ir75b indicating the position of the PTC in the RAL707 strain (an identical sequence is found in all other strains containing a PTC at this position; Methods). The region encoding the epitope recognised by anti-IR75b antibodies is indicated with a red bar.

b, Immunofluorescence with anti-IR75b antibodies on antennae of reference D. melanogaster (Methods) and RAL707 flies. Scale bar = 10 µm.

c, Quantification of odour-evoked responses in ac3 sensilla to propionic acid and butyric acid in control (reference D. melanogaster) and RAL707 flies. Boxplots indicate the median and first and third quartile of the data; each dot corresponds to one recording.

d, Gene structure of D. melanogaster Ir31a indicating the position of the PTC in the RAL441 strain.

e, Quantification of odour-evoked responses to 2-oxopentanoic acid in ac1 sensilla of control (reference D. melanogaster) and RAL441 flies.

f, Gene structure of D. melanogaster Or35a indicating the position of the PTC in the T09 (and T29) strain.

g, Quantification of odour-evoked responses to octanol in ac3 sensilla of control (reference D. melanogaster) and T09 flies.

Our desire to understand the molecular basis of the loss of olfactory sensitivity to acetic acid in D. sechellia led us to discover a surprising and, to our knowledge, unprecedented evolutionary trajectory of a presumed pseudogene: efficient readthrough of the DsecIr75a PTC permits production of a full-length receptor protein, whose reduction in acetic acid sensitivity and gain of responses to other acids is due to lineage-specific amino acid substitutions in the LBD pocket. The PTC does not noticeably influence DsecIR75a’s activity, suggesting that it is selectively neutral. We hypothesise that it became fixed through genetic drift, given D. sechellia’s persistent low effective population size17.

Readthrough of the DsecIr75a PTC cannot be due to insertion of the alternative amino acid selenocysteine (which is incorporated at UGA18). Moreover, no suppressor tRNAs are known in D. melanogaster19, and ribosomal frame-shifting is also unlikely because the reading-frame is the same before and after the PTC. We suggest readthrough is due to PTC recognition by a near-cognate tRNA that allows insertion of an amino acid instead of translation termination. Although the trans-acting factors regulating readthrough are unclear, the neuronal-specificity of this process is reminiscent of RNA editing and microexon splicing, where key responsible regulatory proteins are neuronally-enriched20,21. We speculate that tissue-specific expression differences in tRNA populations underlie neuron-specific readthrough.

Although viruses have long-been appreciated to display PTC readthrough22, case studies in eukaryotes are limited to artificial scenarios where nonsense mutations have been introduced through site-directed or random mutagenesis23–25, or in human disease-causing alleles with low readthrough rates26. Our characterisation of four cases of protein-coding PTC-containing genes demonstrates that readthrough of naturally-occurring PTCs can be sufficiently efficient to permit functionality of “pseudogenes” and maintenance of these variants in populations, This finding further highlights the plasticity of translational regulation to buffer phenotypic consequences of genetic changes27, and begs the experimental examination of the hundreds of PTC-containing presumed pseudogenes, both within and beyond chemosensory gene families in insects28 to humans29.

Methods

Molecular Biology and Transgenesis

D. melanogaster and D. sechellia Ir75a ORFs (including the PTC in DsecIr75a) were cloned into pUAST-attB32. Sequences of cloned ORFs have been deposited in GenBank (Accessions: DmelIr75a (KX694388) and DsecIr75a (KX694389)). Site-directed mutagenesis of DsecIr75a and DmelIr75a, RT-PCR amplification and sequencing of genomic amplicons to verify the presence of the DsecIr75a PTC were performed using standard procedures. For the transgene in which the nucleotide 3’ of the PTC was mutated (Fig. 3e), we changed codon 215 from CGT→AGA to maintain the identity of the encoded amino acid (arginine). Oligonucleotide and plasmid sequences are available upon request. New transgenes were integrated in attP40 using the phiC31 site-specific integration system32 by Genetic Services Inc. or BestGene Inc. All transgenes were sequence-verified both before and after integration into D. melanogaster.

Drosophila Strains

Flies were maintained at 25ºC in 12 h light:12 h dark conditions. D. melanogaster wild-type was w1118, unless noted otherwise. D. sechellia wild-type was #14021-0248.25 (Drosophila Species Stock Center, UCSD). The sequenced region of Ir75a shown in Fig. 1f was amplified from the following strains (from the Drosophila Species Stock Center, unless noted otherwise): D. sechellia: #14021-0248.08, #14021-0248.11, #14021-0248.13, #14021-0248.15, #14021-0248.19, #14021-0248.25, #14021-0248.27, #14021-0248.30; D. simulans: #14021-0251.195, #14021-0251.196, #14021-0251.197, as well as a Seychelles-isolated D. simulans33. Other published mutant and transgenic lines used were: Ir84aGal4 34, Ir75a-Gal411, UAS-CD8:GFP35, Mi{ET1}Ir75a[MB00253]36, Df(3L)BSC415 (Ir75a deficiency)37, actin5C-Gal438, elav-Gal4 (Bloomington #458), repo-Gal4 (Bloomington #7415), RAL441, RAL70739 and Tasmania T0940.

Sequence Analysis

We downloaded D. sechellia antennal RNA-sequencing datasets41 from NCBI’s GEO repository (GEO accessions GSE67861 and GSE67587; SSR files SRR1952772, SRR1952777, SRR1973487, SRR1973490). The sra files were converted to fastq files and remapped to the D. sechellia genome (r1.3) using TopHat (v2.0.13;--b2-sensitive). The genomic index and splicing index were also generated with TopHat using the D. sechellia gtf (r1.3). The resulting bam files were visualised within IGV (v2.3.63), and we manually inspected reads that covered the Ir75a PTC. Within these four datasets ~100% of the reads supported the presence of the PTC-causing “T” allele (only 6/1777 reads within all four data sets supported an alternative nucleotide, within the noise of sequencing errors).

PTCs in other olfactory receptor genes were identified in the Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) (dgrp2.gnets.ncsu.edu/)39 and/or the Global Diversity Lines (GDL)40,42. For Ir75b, the following lines contain the same PTC: DGRP (RAL181, RAL189, RAL227, RAL320, RAL348, RAL352, RAL358, RAL374, RAL379, RAL382, RAL385, RAL395, RAL399, RAL439, RAL461, RAL531, RAL596, RAL707, RAL712, RAL716, RAL730, RAL804, RAL805, RAL821, RAL855, RAL884), GDL (B10, B11, B12, I26, N01, N02, N07, N25, T29). We re-sequenced the PTC-containing region and confirmed IR75b protein expression in all strains from the GDL (data not shown). For Ir31a, only RAL441 contains the PTC. For Or35a, GDL Tasmanian strains T09 and T29 contain the same PTC.

Histology and Morphological Analyses

Immunofluorescence on whole-mount antennae or antennal cryosections (used only in Fig. 1c inset, and Fig. 2a), were performed as described11,13,43. Affinity-antibodies were generated by Proteintech Group, Inc, against the following peptides: KRSKYGNREQLTDVVLRV (anti-IR75a, in rabbits; used at 1:100 for whole-mount antennae, and 1:500 for cryosections), and RPLTLSDDELIRFLSQEND (anti-IR75aD, in guinea pigs; used at 1:10) and PDVRDLYRKKVLGSKRSPD (anti-IR75b, in guinea pigs; used at 1:500), which are predicted antigenic, surface exposed, peptide sequences conserved in D. melanogaster, D. simulans and D. sechellia orthologues. Other antibodies used were (concentrations listed are for whole-mount antennal stainings, for cryosections, antibodies were used at 10-fold higher dilutions): guinea pig anti-IR8a 1:100013, chicken anti-GFP 1:100 (AbCam), rat anti-Elav 1:10 (7E8A10; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) and mouse monoclonal nc82 1:10 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Alexa488-, Cy3- and Cy5-conjugated goat α-mouse IgG, goat anti-guinea pig IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes; Jackson Immunoresearch) were used at 1:100, and Alexa488-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgG secondary antibodies were used at 1:500.

The quantifications in Extended Data Fig. 1 were performed using ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov/ij/). In brief, for each antenna a single plane with several IR75a-positive cells was chosen and cropped to exclude background from the surroundings. The IR75a channel was used to create a mask of the cells by using the auto-threshold function. This mask was then applied to the composite image (with overlapping anti-IR75a in the red channel and anti-GFP in the green channel). The new image was analysed using the “Color Histogram” tool to give the total number of red and green pixels within the masked cells; these values were used to calculate the ratio of green to red pixels.

Electrophysiology

Single sensillum electrophysiological recordings were performed essentially as described44,45 on 2-10 day old animals. The sample sizes (n) indicated in the figures correspond to biological replicates (different sensilla), with a maximum of three sensilla per animal. Exact sample sizes for each experimental/group condition are provided in Source Data. Genotypes (not blinded to experimenter) were interleaved to minimise effects of time-of-day and animal age. All odour-evoked responses were corrected for solvent-evoked spikes. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were of the highest purity available. Odorants were used at 1% (v/v) in all experiments unless otherwise noted in the figure legends. Odour stimulus cartridges (10 μl odour dilution on ~5x5 mm Sugi strip placed in a 2 ml plastic syringe) were prepared freshly before each recording session; cartridges were interleaved, with a maximum of five uses. CAS and solvents are as follows: 1,4-diaminobutane (110-60-1; H2O), 2-oxopentanoic acid (1821-02-9; paraffin oil), acetic acid (64-19-7; H2O), butyric acid 107-92-6; H2O), hexanoic acid (142-62-1; H2O), octanol (111-87-5; paraffin oil), phenylethylamine (64-04-0; paraffin oil), propionic acid (79-09-4; H2O), pyridine (110-86-1; paraffin oil). “IR decoder” neurons are ac4 Ir84a mutant neurons lacking the endogenous ligand-specific IR84a, but which still expresses the co-receptor IR8a34. For measurement of odour-evoked responses of Ir75b neurons in ac3 sensilla (Fig. 5c), we note approximately half of the analysed sensilla belong to “ac3II” class (expressing IR75c) that are electrophysiologically indistinguishable from ac3I sensilla (expressing IR75b) (L.L.P.-G., R.R. and R.B., unpublished data). Thus, if the RAL707 PTC-bearing allele is non-functional, we would expect half of the sensilla to show no responses, which is not the case.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes were fixed prior to data analysis, based upon preliminary studies. Data were analysed and plotted using “R project” (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2005; R-project.org). Data were analysed statistically using the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess for normality followed by a two-tail Student’s t test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. When p value correction for multiple comparisons was needed, the Benjamini & Hochberg method was used. Full statistical test results are provided in the Source Data files for each figure.

Cluster Analysis of Odour Responses

Spike count data (from responses of endogenous or IR decoder neurons) were imported to Matlab (Mathworks), and standardised using z-scores across each recording. An unbiased k-means cluster analysis was performed using the response properties to the indicated number of odours. The optimal number of clusters was determined by the silhouette method46. The silhouette value is a measure of both how tightly a data point is associated with its assigned cluster and how dissimilar it is from other clusters, and it peaks at the “right” number of clusters. If the distribution is unimodal (i.e., all the data fall within one cluster) the silhouette value does not peak and is similar for each value of k. In brief, we first ran iteratively the Matlab k-means algorithm 100 times for k values between 2 and 6. We then calculated the silhouette value for each k-means solution, and subsequently computed and plotted the mean silhouette value and its standard deviation of all of the solutions within each k value. The results of the clusters from the k-mean analysis were plotted in Matlab on the Principal Component space after performing a principal component analysis using the same odour dataset. The script used to analyse data is available upon request.

Protein Homology Modelling

A multiple sequence alignment of the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of D. sechellia IR75a, D. melanogaster antennal IRs (IR8a, IR21a, IR25a, IR31a, IR40a, IR41a, IR64a, IR75a, IR75b, IR75c, IR76a, IR76b, IR84a, IR92a, IR93a)6, Rattus norvegicus GluK2 (UniProt ID P42260), Rattus norvegicus GluA2 (P19491), Adineta vaga GluR1 (E9P5T5) and Synechocystis PCC 6803 GluR0 (P73797) was generated by PROMALS3D47. A GT dipeptide sequence was introduced between the S1 and S2 domains of the Drosophila proteins to facilitate alignment with the linker sequence included in the crystallised GluA2, GluK2 and AvGluR1 LBDs. Alignment of IR75a proteins was curated according to PSIPRED secondary structure predictions48. Models of DsecIR75a LBD (V205-T318--GT--K434-C579) were built using MODELLER (mod9.12)49 using as templates the apo and ligand-bound crystal structures of GluA2 (PDB ID: 1FTO apo state; 1FTM ligand bound50). The results of standard MODELLER energy functions, molpdf and DOPE, were highly similar between generated models. We illustrate in Fig. 4a the model with the lowest DOPE energy function score.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Quantification of efficiency and tissue-specificity of translational readthrough of the D. sechellia Ir75a PTC.

Quantification of GFP staining in the cell bodies of neurons expressing different readthrough reporter constructs in different populations of OSNs (see Fig. 2-3 for genotypes). GFP fluorescence levels were normalised by anti-IR75a fluorescent levels in the Cy3 channel within each analysed cell. Boxplots indicate the median and first and third quartile of the data. Asterisks indicate significance (* p <0.05, *** p <0.0005, n.s. p>0.05) (all pair-wise Wilcoxon-sum-rank-test, Benjamini & Hochberg correction).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Tissue-specificity of translational readthrough of the D. sechellia Ir75a PTC.

Immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (green) and the neuron nuclear marker anti-Elav (magenta) on whole-mount D. melanogaster antennae in which actin5C-Gal4 drives broad expression of DsecIR75a*214Q:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a*214Q:GFP/act5C-Gal4) or DsecIR75a:GFP (UAS-DsecIr75a:GFP/act5C-Gal4). Arrowheads indicate GFP-expressing, Elav-negative, non-neuronal cells that were observed in 6/6 antennae expressing the control transgene lacking the PTC, and in 0/6 antenna expressing the PTC-containing transgene. Note that the neuronal GFP signal of both transgenes is heterogeneous across the antenna, possibly because of variable strength of driver expression and/or instability of the GFP-tagged receptors in heterologous neurons. Scale bars = 10 µm.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Alignment of drosophilid IR75a orthologues.

Protein sequence alignment of D. melanogaster, D. simulans and D. sechellia IR75a. Blue bars indicate the S1 and S2 lobes of the predicted ligand-binding domain (LBD). The position of the premature termination codon (X) is highlighted in yellow. Dark grey columns in the alignment highlight amino acids conserved only in two of the three species. Pink/red shading represent D. sechellia-specific amino acid changes within the LBD; red are the subset located in the internal cavity of the binding pocket (Fig. 4a). The locations of the peptide epitopes for the IR75a antibodies are highlighted with green dashed boxes.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Carmen Carracedo, Pelayo Casares, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537), the Drosophila Species Stock Center (UCSD), and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (NICHD of the NIH, University of Iowa) for reagents. We thank members of the Benton laboratory for discussions and comments on the manuscript. L.L.P.-G. was supported by a FEBS Long-Term Fellowship; R.R. was supported by a Roche Research Foundation Fellowship. J.R.A. was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from Novartis Foundation for medical-biological Research (12A14) M.D.P.’s laboratory was supported by the SNSF. Research in R.B.’s laboratory was supported by ERC Starting Independent Researcher and Consolidator Grants (205202 and 615094), an HFSP Young Investigator Award (RGY0073/2011) and the SNSF Nano-Tera Envirobot project (20NA21_143082).

Footnotes

Author contributions

L.L.P.-G. and R.B. conceived the project. L.L.P.-G., R.R., B.B. and M.D.P. designed experiments. L.L.P.-G., R.R., L.A. and R.B. generated reagents. L.L.P.-G. performed electrophysiology, bioinformatics and histology. R.R. performed electrophysiology and molecular analyses. B.B. generated protein models. L.A. performed histology. J.R.A. performed bioinformatics. L.L.P.-G., R.R., B.B., J.R.A. and R.B. analysed data. L.L.P.-G. and R.B. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Competing Financial Interests

Declared none.

References

- 1.Salmena L. Pseudogene redux with new biological significance. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1167:3–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0835-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poliseno L, et al. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ji Z, Song R, Regev A, Struhl K. Many lncRNAs, 5'UTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nei M, Niimura Y, Nozawa M. The evolution of animal chemosensory receptor gene repertoires: roles of chance and necessity. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:951–963. doi: 10.1038/nrg2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benton R, Vannice KS, Gomez-Diaz C, Vosshall LB. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;136:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croset V, et al. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLOS Genet. 2010;6:e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stensmyr MC. Drosophila sechellia as a model in chemosensory neuroecology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:468–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorter JA, et al. The nutritional and hedonic value of food modulate sexual receptivity in Drosophila melanogaster females. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19441. doi: 10.1038/srep19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becher PG, Bengtsson M, Hansson BS, Witzgall P. Flying the fly: long-range flight behavior of Drosophila melanogaster to attractive odors. J Chem Ecol. 2010;36:599–607. doi: 10.1007/s10886-010-9794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farine JP, Legal L, Moreteau B, Le Quere JL. Volatile components of ripe fruits of Morinda citrifolia and their effects on Drosophila. Phytochemistry. 1995;41:433–438. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silbering AF, et al. Complementary Function and Integrated Wiring of the Evolutionarily Distinct Drosophila Olfactory Subsystems. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:13357–13375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2360-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao CA, Ignell R, Carlson JR. Chemosensory coding by neurons in the coeloconic sensilla of the Drosophila antenna. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8359–8367. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2432-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuin L, et al. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2011;69:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jungreis I, et al. Evidence of abundant stop codon readthrough in Drosophila and other metazoa. Genome Research. 2011;21:2096–2113. doi: 10.1101/gr.119974.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn JG, Foo CK, Belletier NG, Gavis ER, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling reveals pervasive and regulated stop codon readthrough in Drosophila melanogaster. Elife. 2013;2:e01179. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namy O, et al. Identification of stop codon readthrough genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2289–2296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Legrand D, Vautrin D, Lachaise D, Cariou ML. Microsatellite variation suggests a recent fine-scale population structure of Drosophila sechellia, a species endemic of the Seychelles archipelago. Genetica. 2011;139:909–919. doi: 10.1007/s10709-011-9595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shchedrina VA, et al. Analyses of fruit flies that do not express selenoproteins or express the mouse selenoprotein, methionine sulfoxide reductase B1, reveal a role of selenoproteins in stress resistance. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29449–29461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.257600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan PP, Lowe TM. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D93–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O'Connell MA, Reenan RA. dADAR, a Drosophila double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase is highly developmentally regulated and is itself a target for RNA editing. Rna. 2000;6:1004–1018. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irimia M, et al. A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell. 2014;159:1511–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Namy O, Rousset JP. In: Recoding: Expansion of decoding rules enriches gene expression. Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, editors. Springer; 2010. pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopczynski JB, Raff AC, Bonner JJ. Translational readthrough at nonsense mutations in the HSF1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:369–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00538696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washburn T, O'Tousa JE. Nonsense suppression of the major rhodopsin gene of Drosophila. Genetics. 1992;130:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samson ML, Lisbin MJ, White K. Two distinct temperature-sensitive alleles at the elav locus of Drosophila are suppressed nonsense mutations of the same tryptophan codon. Genetics. 1995;141:1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeling KM, Xue X, Gunn G, Bedwell DM. Therapeutics based on stop codon readthrough. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2014;15:371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannathan S, Bradley RK. Translational plasticity facilitates the accumulation of nonsense genetic variants in the human population. bioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1101/gr.205070.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W, et al. Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel lines. Genome Res. 2014;24:1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pei B, et al. The GENCODE pseudogene resource. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R51. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams MD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark AG, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carracedo MC, Asenjo A, Casares P. Genetics of Drosophila simulans male mating discrimination in crosses with D. melanogaster. Heredity. 2003;91:202–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grosjean Y, et al. An olfactory receptor for food-derived odours promotes male courtship in Drosophila. Nature. 2011;478:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellen HJ, et al. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics. 2004;167:761–781. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook RK, et al. The generation of chromosomal deletions to provide extensive coverage and subdivision of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R21. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-r21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ito K, Awano W, Suzuki K, Hiromi Y, Yamamoto D. The Drosophila mushroom body is a quadruple structure of clonal units each of which contains a virtually identical set of neurones and glial cells. Development. 1997;124:761–771. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackay TF, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature. 2012;482:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grenier JK, et al. Global diversity lines - a five-continent reference panel of sequenced Drosophila melanogaster strains. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:593–603. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.015883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiao MS, et al. Expression Divergence of Chemosensory Genes between Drosophila sechellia and Its Sibling Species and Its Implications for Host Shift. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:2843–2858. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arguello JR, et al. Extensive local adaptation within the chemosensory system following Drosophila melanogaster’s global expansion. Nature Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11855. ncomms11855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saina M, Benton R. Visualizing olfactory receptor expression and localization in Drosophila. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1003:211–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-377-0_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benton R, Vannice KS, Vosshall LB. An essential role for a CD36-related receptor in pheromone detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;450:289–293. doi: 10.1038/nature06328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benton R, Dahanukar A. Electrophysiological recording from Drosophila olfactory sensilla. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:824–838. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. Wiley-Interscience; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pei J, Kim BH, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]