Abstract

The checkpoints and mechanisms that contribute to autoantibody-driven disease are as yet incompletely understood. Here we identified the axis of interleukin 23 (IL-23) and the TH17 subset of helper T cells as a decisive factor that controlled the intrinsic inflammatory activity of autoantibodies and triggered the clinical onset of autoimmune arthritis. By instructing B cells in an IL-22- and IL-21-dependent manner, TH17 cells regulated the expression of β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1 in newly differentiating antibody-producing cells and determined the glycosylation profile and activity of immunoglobulin G (IgG) produced by the plasma cells that subsequently emerged. Asymptomatic humans with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-specific autoantibodies showed identical changes in the activity and glycosylation of autoreactive IgG antibodies before shifting to the inflammatory phase of RA; thus, our results identify an IL-23–TH17 cell–dependent pathway that controls autoantibody activity and unmasks a preexisting breach in immunotolerance.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a prototypical and highly prevalent inflammatory disease that is characterized by aggressive autoantibody-induced joint inflammation1. Experimental models have confirmed that arthritis essentially depends on B cells, Fc receptors and complement2–5 and that this disease can be transferred by injection of arthritogenic serum or autoantibodies into healthy animals2,6,7. Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) have been identified accordingly as autoantibodies highly specific to RA in humans8, and B cell depletion has emerged as an efficient therapeutic strategy9. However, ACPAs usually appear several years before the onset of RA10,11, and their titers do not correlate with disease activity or flare frequency12,13. These clinical observations show that systemic autoimmunity and inflammatory disease are not necessarily coupled and indicate as-yet-uncharacterized key checkpoints during autoantibody-driven inflammation.

Apart from B cells and autoantibodies, distinct T cell subsets, in particular the TH17 subset of helper T cells, have been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of RA14. The number of TH17 cells in the peripheral blood of human patients with RA closely correlates with disease activity15, and mice lacking interleukin 23 (IL-23), a cytokine that controls the maintenance as well as the pathogenicity of TH17 cells14, are protected from experimental arthritis16. The IL-23–TH17 axis has been consequently suggested to directly induce joint inflammation, leukocyte activation and osteoclastogenesis14. However, TH17 cells do not predominate within the inflamed joints of patients with RA or arthritic mice17,18. It has therefore remained unclear where, when and how the IL-23–TH17 axis contributes to this autoantibody-driven disease14.

Here we report that IL-23 did not directly affect autoantibody-induced inflammation within joints but controlled the glycosylation profile and the inflammatory activity of newly generated autoantibodies. This pathway, in turn, promoted the transition from asymptomatic autoimmunity to inflammatory autoimmune disease. IL-23-activated TH17 cells accumulated in germinal centers of secondary lymphatic organs during the prodromal phase of experimental arthritis, where they suppressed sialyltransferase expression in differentiating plasmablasts. The consecutive change in the glycosylation profile of immunoglobulin G (IgG) elicited a shift toward a pro-inflammatory autoantibody repertoire and triggered the onset of arthritis. Plasmablasts from patients with RA similarly displayed diminished sialyltransferase activity, while IgG from these patients showed corresponding changes in its glycosylation profile, as well as increased inflammatory activity, which suggests that related pathways might contribute to the onset and progression of autoantibody-mediated diseases in humans.

Results

IL-23 determines the onset but not the effector phase of arthritis

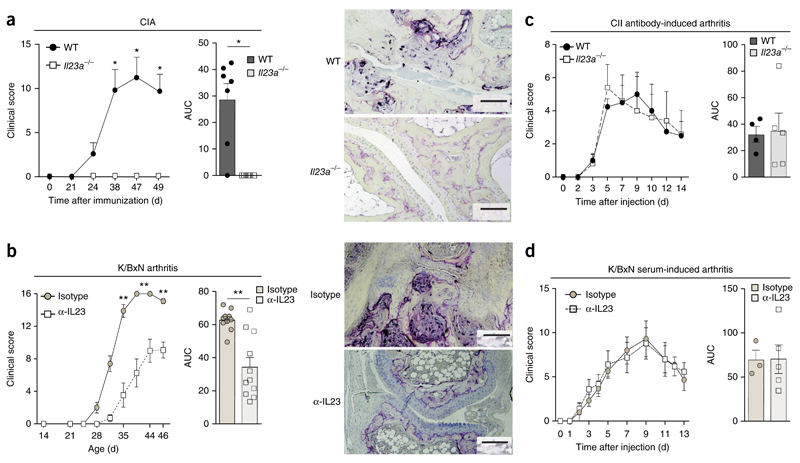

In an effort to elucidate the specific role of IL-23 during the pathogenesis of RA, we sought to delineate its contributions to various phases of autoimmune-driven arthritis. Therefore, we used mice deficient in the IL-23-specific subunit p19 (Il23a−/− mice) or, alternatively, applied an antibody directed against mouse IL-23p19 to neutralize IL-23 in vivo, and studied the models of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA)7 and K/BxN arthritis2,6. During CIA, mice form arthritogenic autoantibodies to type II collagen (CII) in response to active immunization with CII, whereas K/BxN mice spontaneously develop arthritogenic autoantibodies to glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI). Both models are characterized by an initial break in self-tolerance, the appearance of arthritogenic autoantibodies and the subsequent development of autoantibody-induced joint inflammation and thus reflect the key immunological and clinical features of human RA1, to which CII and GPI have been likewise linked as potential autoantigens19. By studying the clinical course of CIA and K/BxN arthritis, as well as that of the arthritis that develops after passive transfer of the corresponding autoantibodies, we aimed to determine the individual roles of IL-23 during the initiation and subsequent autoantibody-mediated effector phase of arthritis. CIA developed in wild-type mice but not in Il23a−/− mice (Fig. 1a). Neutralization of IL-23 with the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody (continuous application of 5 mg antibody per kg body weight from day 14 after birth, twice a week, unless specified otherwise) resulted in substantial suppression of the spontaneous arthritis in K/BxN mice, whereas treatment with an IgG isotype-matched control antibody did not interfere with development of disease in these mice (Fig. 1b). However, we did not detect any difference in arthritis severity after we injected CII-specific antibodies into wild-type mice and Il23a−/− mice (Fig. 1c). Also, passive transfer of serum from arthritic K/BxN mice induced arthritis of equal severity in wild-type mice and Il23a−/− mice, as well as in wild-type mice that received continuous injections of the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody or the corresponding IgG isotype-matched control antibody (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1). These data suggested that IL-23-dependent mechanisms were essential for the induction of an arthritogenic autoantibody response during CIA and in K/BxN mice but did not contribute to the autoantibody-mediated inflammatory effector phase of arthritis that subsequently developed.

Figure 1. IL-23 contributes to the initiation but not the effector phase of autoantibody-mediated arthritis.

(a) Clinical arthritis scores of C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (n = 7) and Il23a−/− mice (n = 6) after the induction of CIA (left), summarized as area under the curve (AUC) (middle), and microscopy of the ankle joints of such mice, stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase for visualization of osteoclast formation and joint destruction (right) (n ≥ 5 mice per genotype). (b) Clinical arthritis scores of K/BxN mice treated with neutralizing antibody to IL-23p19 (α-IL-23) (n = 10 mice) or isotype-matched control antibody (Isotype) (n = 11 mice) (left and middle, presented as in a), and microcopy of ankle joints, stained as in a (n ≥ 5 mice per group) (right). (c,d) Clinical arthritis scores of wild-type mice (n = 4) and Il23a−/− mice (n = 5) that received CII-specific antibodies (c) or wild-type mice that received serum from arthritic K/BxN mice together with a neutralizing antibody to IL-23p19 (n = 3 mice) or isotype-matched control antibody (n = 5 mice). Scale bars (a,b), 100 μm. Each symbol (middle (a,b) or right (c,d)) represents an individual mouse. P = 0.89 (c) and P = 0.98 (d); *P ≤ 0.01 and **P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.).

IL-23 defines the inflammatory activity of autoantibodies

To understand the effect of IL-23 on the humoral autoimmune response during CIA and K/BxN arthritis in more detail, we measured the corresponding arthritogenic autoantibodies to CII and GPI in serum. Despite the finding that they were protected from CIA, Il23a−/− mice developed titers of CII-specific IgG similar to those of their arthritic wild-type littermates (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Similarly, GPI-specific antibody titers in K/BxN mice that had received the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody did not differ from the titers in those that received the corresponding IgG isotype-matched control antibody (Fig. 2b). These findings indicated a disconnection between the development of humoral autoimmunity and the onset of arthritis in the absence of IL-23. Notably, CII-specific autoantibodies in Il23a−/− mice and their wild-type littermates did not differ in isotype composition, epitope specificity or affinity, as determined by ELISA, murine CII-epitope bead array and potassium-thiocyanate-titration assay, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2b–e). Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry revealed that wild-type mice and Il23a−/− mice also had a similar number of germinal centers and germinal-center B cells during CIA (Supplementary Fig. 2f,g) and generated similar titers of high-affinity antibodies to other model antigens, such as 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (Supplementary Fig. 2h), suggestive of normal affinity maturation in the absence of IL-23.

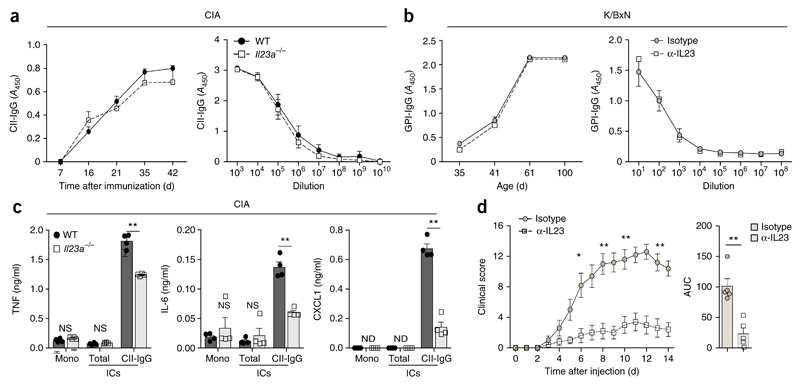

Figure 2. IL-23 promotes the inflammatory activity of autoreactive IgG.

(a,b) Concentration (left) and titers (right) of CII-specific IgG (CII-IgG) during CIA in wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n ≥ 3 per genotype) (a) and of IgG directed against GPI (GPI-IgG) in K/BxN mice that received neutralizing antibody to IL-23p19 or isotype-matched control antibody (n ≥ 3 mice per group) (b); results are presented as absorbance at 450 nm (A450). (c) ELISA of cytokines TNF, IL-6 and CXCL1 in supernatants of wild-type BMDCs incubated for 24 h with monomeric IgG (Mono) or ICs consisting of total (heat-aggregated) IgG (Total) or CII-specific IgG (CII-IgG), generated from IgG isolated from the serum of wild-type or Il23a−/− mice (n = 4 per group) on day 50 after the induction of CIA. (d) Clinical arthritis scores of wild-type mice (n = 5 per group) after transfer of serum from K/BxN mice that had received neutralizing antibody to IL-23p19 or isotype-matched control antibody. Each symbol (c, and d, right) represents an individual biological replicate (c) or mouse (d, right). ND, not detectable. P = 0.2 (a) or P = 0.48 (b); NS, not significant (P > 0.05); *P ≤ 0.01 and **P ≤ 0.001 (P ≤ 0.0002 in c) (Student’s t test). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.).

Next we assessed the effect of IL-23 on the inflammatory activity of distinct immunoglobulin fractions after the onset of arthritis. At 50 d after induction of CIA, protein-G-purified IgG from the serum of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice was used to generate either nonspecific immunocomplexes (ICs) or CII-specific ICs. To test the inflammatory potential of these different classes of ICs, we incubated them with bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from wild-type mice and performed ELISA-based measurement of the IC-induced concentrations of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF and CXCL1 in the BMDC supernatants. Incubation of BMDCs with monomeric IgG or nonspecific ICs from either wild-type mice or Il23a−/− mice induced negligible amounts of these inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2c). In contrast, incubation of BMDCs with CII-specific ICs isolated from wild-type mice triggered robust production of these inflammatory mediators (Fig. 2c). Notably, this potential of CII-specific ICs to induce cytokines was present mainly in IgG isolated from the serum of wild-type mice, whereas CII-specific ICs isolated from the serum of Il23a−/− mice displayed diminished inflammatory activity and induced significantly lower concentrations of cytokines in BMDCs (Fig. 2c). These data indicated that the inflammatory properties of CII-specific ICs were IL-23 dependent. We consequently determined the contribution of IL-23 to the inflammatory activity of K/BxN serum and investigated whether blockade of IL-23 in K/BxN mice would alter the capacity of their serum to induce serum-transfer arthritis. Serum from K/BxN mice treated with the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody (collected weekly at weeks 6–12) showed much lower potential to induce arthritis in wild-type mice than did serum from K/BxN mice treated with IgG isotype-matched control antibody, although the neutralization of IL-23 had no effect on the titers of GPI-specific autoantibodies in these mice (Fig. 2b,d). Together these data showed that IL-23 acted as a decisive factor during the generation of the inflammatory and arthritogenic autoantibody repertoire.

IL-23 unlocks autoantibody activity via IgG glycosylation

To determine the molecular correlate for the IL-23-dependent increase in the pro-inflammatory activity of autoantibodies, we performed mass spectrometry of purified total IgG, nonspecific IgG that had been depleted of CII-specific IgG, and CII-specific IgG from wild-type and Il23a−/− mice on day 50 after the induction of CIA. CII-specific IgG from wild-type mice had a lower sialic acid content at Asn297 within the Fc region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain than that of nonspecific IgG (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3). Such diminished IgG sialylation, however, was not present in the CII-specific antibodies of Il23a−/− mice (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3), indicative of an IL-23-mediated decrease in the sialylation of CII-specific antibodies during onset of CIA. The content of galactose or fucose at Asn297 did not differ among the groups of IgG analyzed (Fig. 3a). Terminal sialic acid residues of Asn297 have been linked to the regulation of IgG conformation and interfere with the pro-inflammatory potential of IgG20, which suggests that the IL-23-mediated increase in the inflammatory activity of CII-specific IgG was potentially linked to the diminished sialylation of Asn297 in CII-specific IgG.

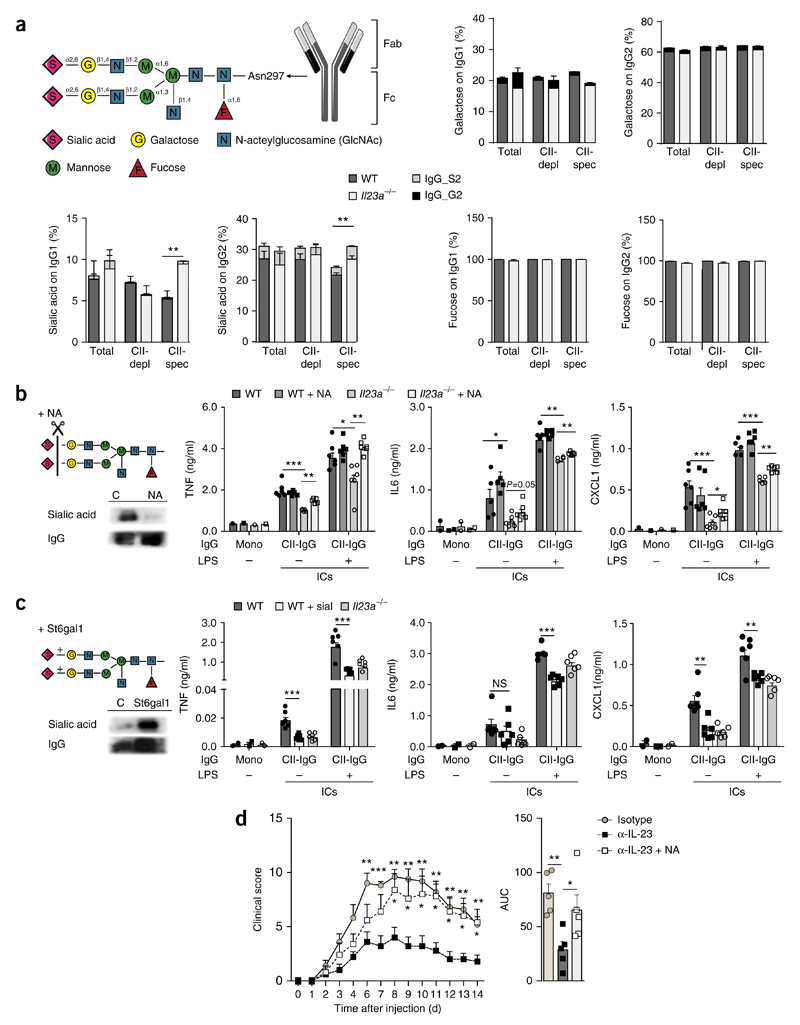

Figure 3. IL-23 regulates the inflammatory activity of autoantibodies via altering glycosylation of autoantibodies.

(a) Structure of the Asn297-linked sugar moieties on IgG (top left), and mass-spectrometry-based analysis (top right and bottom) of sialic acid, galactose and fucose at Asn297 of total IgG1 or IgG2 (Total), total IgG1 or IgG2 after depletion of CII-specific IgG (CII-depl) and CII-specific IgG1 or IgG2 (CII-spec) obtained from wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n = 4 per genotype) on day 50 after the induction CIA, as well as bisialylated IgG (IgG_S2) or bigalactosylated IgG (IgG_G2) in the fraction of sialylated IgG or galactosylated IgG, respectively. (b,c) ELISA (right) of cytokines TNF, IL-6 and CXCL1 in supernatants of wild-type BMDCs incubated for 24 h, in the presence (+) or absence (−) of LPS (1 ng/ml), with monomeric IgG or CII-specific IgG ICs (CII-IgG), generated from IgG obtained from wild-type or Il23a−/− mice on day 50 after the induction of CIA, assessed before and after (+ NA) the neuraminidase-mediated removal of sialic acid (b) or before and after (+ sial) the St6gal1-mediated addition of sialic acid (c). Far left, sugar moieties on IgG with the removal (b) or addition (c; left lane) of sialic acid (top left), and immunoblot analysis of sialic acid and IgG in samples before (C; left lane) and after the removal (NA; b) or addition (St6gal1; c) of sialic acid (bottom left). (d) Clinical arthritis scores (presented as in Fig. 1a) of wild-type mice (n = 5 per group) after transfer of purified IgG from K/BxN mice treated with isotype-matched control antibody (Isotype) or neutralizing antibody to IL-23 (α-IL-23), or neuraminidase-treated IgG from K/BxN mice treated with antibody to IL-23 (α-IL-23 + NA) (key). Each symbol (b,c, and d, right) represents an individual biological replicate (b,c) or mouse (d). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test). Data are representative of two experiments (a,d; error bars, s.e.m.) or three experiments (b,c; error bars, s.e.m. of n = 6 biological replicates).

To address that hypothesis experimentally, we isolated IgG from the serum of wild-type mice and Il23a−/− mice on day 50 after the induction of CIA and removed the terminal sialic acid at Asn297 in IgG by neuraminidase-mediated digestion or, alternatively, added additional sialic acid by incubating IgG from wild-type mice with recombinant sialyltransferase. We determined the inflammatory activity of the CII-specific ICs generated from these enzymatically modified IgG fractions by measuring the secretion of IL-6, TNF and CXCL1 from wild-type BMDCs incubated with these ICs. Neuraminidase-mediated removal of sialic acid did not affect the cytokine secretion induced by CII-specific ICs from wild-type mice relative to that induced by unmodified CII-specific ICs, but such removal substantially increased the cytokine secretion triggered by CII-specific ICs from Il23a−/− mice relative to that induced by unmodified CII-specific ICs (Fig. 3b). The sialyltransferase-mediated addition of sialic acid to the IgG of wild-type mice, on the other hand, resulted in diminished inflammatory activity of the resulting CII-specific ICs, as they showed lower potential to induce cytokine secretion by BMDCs than did unmodified CII-specific ICs (Fig. 3c). These data showed that the diminished inflammatory activity of CII-specific antibodies from Il23a−/− mice could be attributed to the increased sialylation of this IgG fraction.

Next we isolated IgG from the serum of K/BxN mice treated with the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody or the corresponding IgG isotype-matched antibody, as a control. The neutralization of IL-23 in K/BxN mice abolished the ability of their IgG to induce arthritis when transferred into wild-type control mice (Fig. 3d). However, neuraminidase-mediated removal of sialic acid in IgG isolated from K/BxN mice treated with the IL-23p19-neutralizing antibody restored the ability of this IgG to induce arthritis to a degree similar to that of IgG from K/BxN mice treated with IgG isotype-matched control antibody (Fig. 3c). These data indicated that IL-23 was required for a decrease in the sialylation of arthritogenic IgG antibodies that directly resulted in an increase in its inflammatory activity and the onset of arthritis.

IL-23 regulates sialyltransferase expression in plasma cells

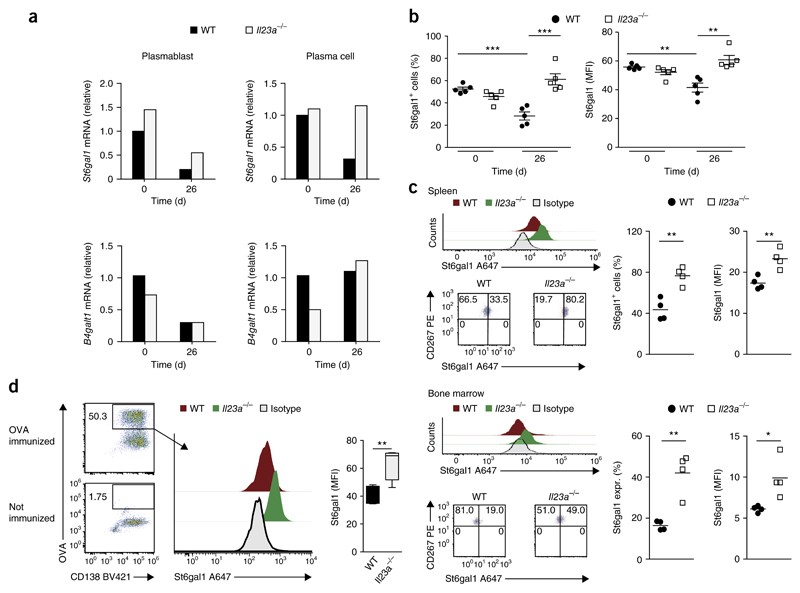

The enzyme β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (St6gal1) acts as the rate-limiting enzyme during the post-translational transfer of sialic acid to the IgG-linked N-glycans in antibody-producing cells21. To delineate the mechanisms underlying the IL-23-mediated control of autoantibody glycosylation, we analyzed the expression of St6gal1 mRNA and St6gal1 protein in plasmablasts and plasma cells from the spleen and bone marrow of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice before and at various time points after the induction of CIA. Whereas we detected no difference between genotypes in St6gal1 expression before the induction of CIA (day 0), the expression of both St6gal1 mRNA and St6gal1 protein decreased during the prodromal phase of CIA (day 26) in antibody-producing cells in wild-type mice but not in Il23a−/− mice (Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Fig. 4a,b); this suggested that IL-23 directly or indirectly suppressed the expression of St6gal1 in developing plasma cells before the onset of CIA. In addition, we immunized wild-type and Il23a−/− mice with ovalbumin (OVA) in the presence of complete Freund’s adjuvant and used fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled OVA to track individual and newly generated OVA-specific plasma cells in the immunized mice. Flow cytometry showed significantly higher expression of St6gal1 in Il23–/– OVA-specific B220loCD138+CD267+ plasma cells than in their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 4d). Together these results indicated that IL-23 promoted the downregulation of St6gal1 expression in newly formed antibody-producing cells during the prodromal phase of arthritis and in response to antigen-specific immunization.

Figure 4. St6gal1 expression in antibody-producing cells is negatively regulated by IL-23.

(a) Expression of St6gal1 mRNA and mRNA encoding β-1,4-galactosyltransferase 1 (B4galt1 mRNA) in sorted plasmablasts (CD3−CD4−GR1−B220+CD138+) and plasma cells (CD3−CD4−GR1−B220−CD138+) pooled from spleens of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice on days 0 and 26 after the induction of CIA (sorting strategy, Supplementary Fig. 4a); results are presented relative to those of wild-type cells at day 0, set as 1. (b) Flow-cytometry-based quantification of St6gal1 expression in antibody-producing cells of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n = 5 per group) at day 0 (healthy control) and day 26 (5 d after secondary immunization) after the induction of CIA, presented as percent St6gal1+ cells (left) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of St6gal1 (right). (c) Flow-cytometry-based quantification of St6gal1 expression in plasma cells from the spleen (top group) and bone marrow (bottom group) of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n = 4 per group) on day 50 after the induction of CIA, presented as in b (right), and flow cytometry of St6gal1 (top left) and of CD267 and St6gal1 (bottom left) in such cells. Numbers in quadrants (bottom right) indicate percent cells in each. During flow cytometry, plasma cells were defined as B220loCD138+CD267+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 4b). (d) Flow cytometry of plasma cells from wild-type mice without immunization (bottom left) or on day 26 after immunization with OVA (top left), and flow-cytometry-based analysis of St6gal1 expression in OVA-specific plasma cells (gated as at left) from wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n = 4 per group) on day 26 after immunization with OVA (right). Numbers adjacent to outlined areas (left) indicate percent OVA-specific CD138+ cells. Each symbol (b,c) represents an individual mouse; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± s.e.m. in b). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m.).

TH17 cells suppress St6gal1 expression in plasma cells

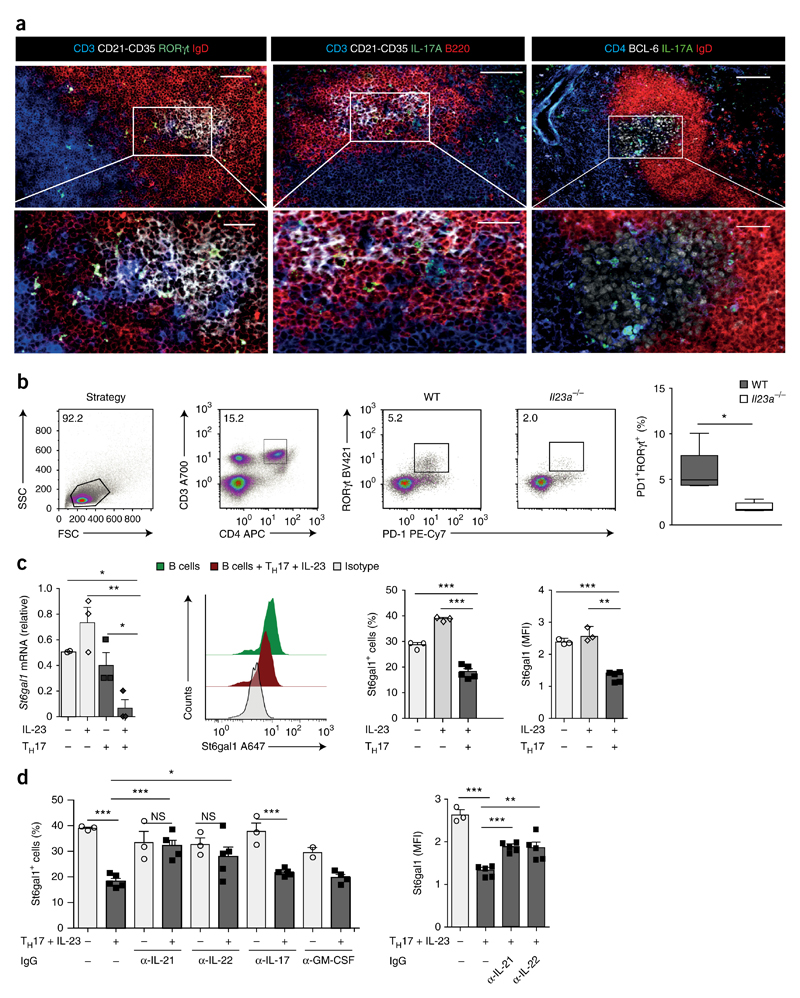

To explore the mechanisms underlying the IL-23-mediated suppression of St6gal1 in plasma cells, we next characterized in more detail the IL-23-dependent TH17 response in secondary lymphatic organs and joints during CIA in wild-type mice. Flow cytometry showed that IL-17-expressing CD3+ T cells were present in spleen and lymph nodes at steady state and during the onset of arthritis (from day 0 to day 42 after the induction of CIA) (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Starting from day 5 after the induction of CIA, we additionally detected a population of IL-17+ CD3+CD4+ T cells in the spleen that co-expressed IL-17 and IL-22 and that was absent at steady state (Supplementary Fig. 5d). In contrast, IL-17A-expressing CD3+ T cells were almost undetectable in the joints of healthy mice or in mice before and after onset of arthritis (at day 0 and days 26 and 42 after the induction of CIA) (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that the IL-17+ and RORγt+CD3+ T cells that appeared in the spleen resided in clusters of IgD−B220+CD21-CD35+ follicular B cells that expressed the transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5e), which identified these structures as newly formed germinal centers. Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry additionally revealed that the IL-17+ and RORγt+ T cells displayed markers of follicular helper T cells, such as Bcl-6 and PD-1 (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 5e). In accordance with the proposal of a key role for IL-23 in the maintenance and induction of a pathogenic TH17 response during the prodromal phase of arthritis, we observed significantly fewer RORγt+PD-1+ TH17 cells in the spleen of Il23a−/− mice than in that of wild-type mice, at day 26 after induction of CIA (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. IL-23-activated TH17 cells suppress St6gal1 expression in antibody-producing cells via IL-21 and IL-22.

(a) Immunofluorescence microscopy of RORγt+ and IL-17+ T cells from wild-type mice at day 26 after the induction of CIA, showing B cell follicles and germinal centers identified by staining for CD21-CD35 or Bcl-6 (all white), TH17 cells identified by staining for CD3 or CD4 (all blue) and IL-17A or RORγt (all green), and B cells identified by staining for B220 or IgD (all red); areas outlined in top row are enlarged below. Scale bars, 200 μm (top) or 100 μm (bottom). (b) Flow-cytometry-based quantification of the frequency of RORγt+PD-1+ TH17 cells in the spleen of wild-type and Il23a−/− mice (n = 5 per group) at day 26 after the induction of CIA (far right), and strategy used for gating those cells (left and middle). (c) Expression of St6gal1 mRNA (far left; n = 3 biological replicates) and flow-cytometry-based quantification of St6gal1 (middle and far right; n = 3–5; presented as in Fig. 4c) in plasma cells differentiated in vitro after co-incubation with various combinations (below plots) of IL-23 (25 ng/ml) and/or in vitro–differentiated TH17 cells; mRNA results are presented relative those of unstimulated splenic B cells. Middle left, flow cytometry of St6gal1 in B cells cultured alone or together with in vitro–generated and IL-23-activated TH17 cells (key). (d) St6gal1 expression (presented as in Fig. 4c) in differentiating plasma cells (n = 3–5 biological replicates) cultivated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of in vitro–generated and IL-23-activated TH17 cells and with or without (−) IgG antibody to IL-21 (α-IL-21), IL-22 (α-IL-22), IL-17A and IL-17F (α-IL-17) or GM-CSF (α-GM-CSF). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (error bars (b–d), s.e.m.).

Next we sought to identify potential TH17 cell–derived signals that might regulate St6gal1 expression in developing plasma cells. For this, we used an in vitro co-culture system of TH17 cells and naive splenic B cells in which the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells was initiated by the addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The stimulation of B cells with IL-23 alone or the co-incubation of B cells with TH17 cells did not result in suppression of the expression of St6gal1 mRNA or St6gal1 protein in developing plasma cells (Fig. 5c). The co-incubation of B cells with IL-23-stimulated TH17 cells, however, resulted in significant inhibition of the expression of St6gal1 mRNA and St6gal1 protein in the developing plasma cells relative to their expression in plasma cells from cultures of LPS-stimulated B cells incubated with TH17 cells or IL-23 only (Fig. 5c). These findings indicated that IL-23 induced a phenotypic switch in the TH17 cells that enabled them to suppress St6gal1 in antibody-producing cells. Antibody-mediated blockade of IL-21 or IL-22 reversed the IL-23–TH17 cell–mediated inhibition of St6gal1 expression in developing plasma cells, but antibody-mediated blockade of IL-17A and IL-17F or of the cytokine GM-CSF did not (Fig. 5d); this demonstrated that IL-23-activated TH17 cells were able to suppress St6gal1 expression in an IL-21- and IL-22-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 5f). We did not detect expression of the IL-22 receptor on naive splenic B cells from wild-type mice; however, we observed an upregulation of the expression of mRNA and protein for this receptor in B cells in which we had initiated plasma cell differentiation by the addition of LPS, as well as in splenic B cells at day 26 after the induction of CIA (Supplementary Fig. 5g–i). These data suggested that B cells gained the ability to respond to T cell–derived IL-22 during plasma cell differentiation and during the prodromal stage of autoimmune arthritis.

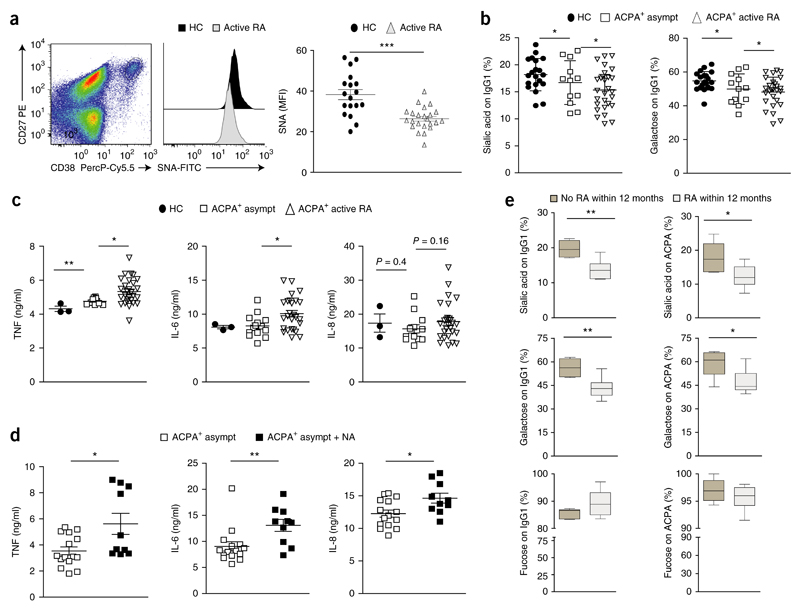

Diminished IgG sialylation parallels the clinical onset of RA

To determine if changes related to those noted above parallel the onset of clinical disease in human RA, we next sought to analyze the activity of sialyltransferases in antibody-producing cells of patients with RA and healthy control subjects. As a ‘readout’ for sialyltransferase activity, we used fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled Sambucus nigra (SNA) lectin to measured sialic acid on the surface of CD27hiCD38hiCD19+ plasmablasts in the peripheral blood of healthy control subjects and ACPA+ patients with RA. Control experiments showed that wild-type B cells, but not those from St6gal1-deficient mice, stained positively for SNA lectin (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c), which confirmed the hypothesis that the extent of SNA binding could serve as a suitable surrogate marker for sialyltransferase activity in B cells. Plasmablasts in the peripheral blood of ACPA+ patients with RA showed significantly lower sialic acid surface content than that of plasmablasts from healthy control subjects (Fig. 6a), which demonstrated diminished sialyltransferase activity in antibody-producing cells of patients with RA.

Figure 6. A decrease in plasmablast sialyltransferse activity and IgG sialylation parallels the clinical onset of RA.

(a) SNA-lectin-based quantification of surface sialic acid on CD27hiCD38hiCD19+ plasmablasts from healthy control subjects (HC) (n = 18) and patients with active RA (n = 23) (middle and right). Left, gating of blood plasmablasts (pregated on CD19+ cells); outlined area indicates CD27+CD38+ cells. (b) Mass-spectrometry-based analysis of the sialic acid and galactose content at Asn297 of total IgG from healthy control subjects (HC), asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects that had not yet developed RA (ACPA+ asympt) or ACPA+ patients with active RA (ACPA+ active RA). (c) ELISA of cytokines TNF, IL-6 and IL-8 in supernatants of in vitro–generated monocyte-derived dendritic cells (from healthy human donors) incubated for 14 h with heat-aggregated IgG ICs generated from donors as in b (key). (d) ELISA of cytokines (as in c) in supernatants of in vitro–generated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells incubated with heat-aggregated ICs from asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects, assessed before (ACPA+ asymp) and after (ACPA+ asymp + NA) the neuraminidase-mediated removal of sialic acid (P ≤ 0.02). (e) Sialylation, galactosylation and fucosylation at Asn297 of total IgG1 (on IgG1) and ACPA-specific IgG1 (on ACPA) from asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects (n = 6 per group) that did not develop RA (No RA within12 months) or developed RA within the following year (RA within 12 months). Each symbol (a–d) represents an individual donor; small horizontal lines indicate the mean (± s.e.m.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (P ≤ 0.0001 in a) (Student’s t-test (a,c–e) or ordinary one-way ANOVA (b)). Data are representative of one experiment per donor (a,b,e; error bars (e), s.e.m.) or three experiments (c,d).

We subsequently assessed the IgG-glycosylation pattern at Asn297 in IgG of serum collected from healthy human control subjects, asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects who had not yet developed RA, and ACPA+ patients with active RA. This analysis indicated less sialylation and galactosylation of IgG in ACPA+ subjects than in healthy control subjects, with the IgG of patients with active RA showing the lowest content of sialic acid (Fig. 6b). To measure the intrinsic inflammatory activity of the IgG from these groups of patients, we generated heat-aggregated ICs from the purified IgG, incubated them with human monocyte-derived dendritic cells from healthy donors and determined the IC-induced cytokine response by measuring IL-6, TNF and IL-8 in the cellular supernatant by ELISA. We observed that ICs from patients with active RA triggered greater production of TNF and IL-6 than did ICs from healthy control subjects or asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects (Fig. 6c). The treatment of IgG from asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects with neuraminidase, in turn, resulted in an increase in its pro-inflammatory potential (Fig. 6d), which indicated that the sialylation of IgG regulated the activity of IgG in ACPA+ subjects. Analysis of the glycosylation status of IgG in a cohort of asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects revealed that the subgroup that subsequently developed RA within 12 months had already displayed significant less sialylation and galactosylation of IgG and of ACPAs before the onset of arthritis than that of ACPA+ subjects who remained healthy throughout the 12-month period (Fig. 6e). Together these data showed that the onset of RA was paralleled by diminished sialyltransferase activity in plasmablasts and less sialylation of RA-specific autoantibodies, which was a predictive factor for the progression to active RA.

Discussion

Here we found that IL-23-activated TH17 cells accumulated in germinal centers before the onset of arthritis, and there they downregulated expression of the sialyltransferase St6gal1 in newly developing plasmablasts and plasma cells in an IL-22- and IL-21-dependent manner. This T cell–driven reprogramming of the antibody-producing cells was paralleled by diminished glycosylation of autoantibodies, which unlocked their inflammatory potential and triggered the onset of arthritis. In contrast, IL-23 was dispensable during the following autoantibody-mediated phase of joint inflammation. These findings are in accordance with the fact that therapeutic targeting of IL-23 is effective during the prodromal phase of autoimmune arthritis but is ineffective after disease onset22.

TH17 cells can provide help to B cells, can promote IgG class switching and have been linked to germinal-center formation23–26. However, our data indicated that IL-23-mediated activation of TH17 cells, which promoted a pathogenic switch in this T cell subset, was not essential for their basic helper T cell ability, as IL-23-deficient mice displayed no alteration in germinal centers or the production of autoreactive IgG. Notably, the glycosylation and activity of total IgG was also unaffected by absence of IL-23, which demonstrates that this cytokine specifically affects the glycostructure of an IgG subset and is in line with data showing that ACPAs from patients with RA similarly exhibit a specific Fc-linked glycan profile that is distinct from that of total serum IgG27. Together with the observation that autoantibody glycosylation changes before the onset of RA28, these findings suggest that the TH17 cell–mediated control of ST6gal1 expression in antibody-producing cells resulted from an individual antigen-specific T cell–B cell interaction in the germinal center, before the onset of autoimmune arthritis. That, in turn, would indicate that the TH17 cell–mediated control of IgG sialylation affects mainly antibodies that target antigens derived from an environment that had elicited an IL-23-driven TH17 response. In accordance, T cell–dependent versus T cell–independent immunization protocols directed against model antigens such as OVA or TNP have been shown to result in distinct glycosylation patterns of the antigen-specific IgG response29,30. Plasma cell development thus seems to follow a default program that usually involves high expression of St6gal1 and results in the production of neutralizing, highly sialylated and non-inflammatory antibodies. However, IL-23-dependent accumulation of follicular helper T cells that display a TH17 signature and specific TH17 cell–derived cytokines such as IL-22 seem to promote the suppression of St6gal1 in antibody-producing cells and can thereby promote a shift to a pro-inflammatory antibody repertoire. This pathway eventually unmasks a preexisting breach in humoral immunotolerance and can initiate the transition from a stage of asymptomatic autoimmunity to inflammatory autoimmune disease.

Although the autoantibodies of arthritic mice and IgG of patients with active RA displayed analogous alterations in sialylation, these changes were less pronounced in humans. However, our analysis of total IgG from individual patients might underestimate the actual decrease in the sialylation of functionally relevant RA autoantibodies in humans, as these are still incompletely defined. While our data did not reveal an effect of IL-23 on the galactosylation of IgG in arthritic mice, diminished galactosylation of IgG has been observed in patients with RA28, suggestive of species-specific differences and additional factors that control the glycosylation of IgG during human disease.

It is well established that asymptomatic autoimmunity and autoantibody formation precede, by several years, the symptomatic inflammatory phase in diseases such as RA1. However, so far it has been unclear how and when autoimmunity progresses to inflammatory disease. Our current work suggests that activation of the IL-23–TH17 axis acts as a ‘second hit’ and promotes this transition to clinical disease. Although TH17 cells have been indicated to be key participants in RA, targeting of IL-17 has only moderate potency in inducing clinical remission in human patients with active RA31. Our current data provide a molecular explanation for the puzzling results of such clinical trials and in turn suggest that during autoantibody-induced diseases like RA, targeting of the IL-23–TH17 axis might be more efficient as a preventive treatment or as part of a therapeutic strategy during the maintenance of clinical remission after B cell depletion.

Online Methods

Animals

Mice were housed in the animal facility of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. Il23a−/− mice32 were backcrossed on a C57BL/6 genetic background for 12 generations. Wild-type and Il23a−/− mice used were co-housed littermates and used for experiments at an age of 10–12 weeks. Male KRN mice (with transgenic expression of a T cell antigen receptor) were bred to NOD mice to generate K/BxN mice. The local ethic committee of the government of Mittelfranken approved all experiments. For the analysis of T cell subsets during CIA (Supplementary Fig. 3c–e), we relied on wild-type DBA mice.

Induction and evaluation of arthritis

For CIA, C57BL6 mice were immunized intradermally with 200 μg of chicken type II collagen (Sigma C-930) together with 250 μg of heat-inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (BD, 231141) emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma) on day 0 and day 21. DBA/1 mice were immunized with 100 μg bovine type II collagen and 100 μg heat-inactivated M. tuberculosis emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on day 0 and boosted with 50 μg in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on day 21.

Collagen-antibody-induced arthritis was induced by a cocktail containing M2139 (γ2b), CIIC1 (γ2a), CIIC2 (γ2b), and UL1 (γ2b) monoclonal antibodies binding to triple helical J1 [MP*GERGAAGIAGPK; P* indicates hydroxyproline], C1 (GARGLTGRO), D3 (RGAQGPOGATGF), and U1 (GLVGPRGERGF) CII epitopes. The cocktail was provided by MD Bioscience. 4 mg of total IgG was injected on two consecutive days and mice additionally received LPS (25 μg per mouse, intraperitoneally) at day 5 as a secondary stimulant33.

K/BxN arthritis spontaneously develops in the F1 generation of KRN mice crossed to NOD mice and has been described before2. During anti-IL-23 blockade, mice received 5 mg anti-IL-23p19 per kg body weight (5B5; fully mouse IgG1) or a similar amount of isotype-matched control antibody twice a week starting treatment on day 14 after birth. 5B5 was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim and displayed an IC50/IC90 ratio during the inhibition of IL-17A secretion from mouse IL-23-stimulated splenocytes of 5 ± 0.2/66 ± 43 nM.

K/BxN serum transfer-induced arthritis was induced by one intraperitoneal injection of 150 μl K/BxN serum (harvested from arthritic K/BxN mice) or 2 mg of purified IgG into control mice.

Clinical arthritis severity was graded by scoring each limb on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 = no erythema of swelling; 1 = mild swelling on erythema of ankle, wrist or individual digits; 2 = moderate, but defined erythema and swelling of ankle or wrist; 3 = severe erythema and swelling extending from the entire paw including digits; and 4 = maximal swelled limb with involvement of multiple joints. The total clinical score was determined by adding the individual scores for each limb. Scoring was performed by an investigator ‘blinded’ to sample identity.

Immunization against OVA

8- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized intradermally with 200 μg of chicken-derived OVA (Sigma) together with 250 μg of heat-inactivated M. tuberculosis H37RA (BD, 231141) emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma) on day 0 and day 21. Splenic OVA-specific plasmablasts were analyzed for St6gal-1 on day 0 and day 26.

Lectin blotting

IgG was resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel under reducing conditions, transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked with 3% deglycosylated gelatin (Sigma). Blots were incubated with biotinylated sambucus nigra lectin (2μg/ml) for sialic acid or lens culinaris agglutinin (5 μg/ml, all Vector Laboratories) for the detection of the core glycan, followed by incubation with streptavidin-HRP and detection via Pierce ECL (Thermo-Scientific).

Specific IgG and cytokine detection via ELISA

Collagen type II (CII)- and GPI specific antibodies were detected by ELISA using high-binding plates (Nunc) coated overnight with 10 μg/ml mouse or chicken CII or with 1 μg/ml GPI.

Total IgG and IgG subclass detection was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The detection of mouse CII-specific antibodies were carried out by Eu3+-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody and the DELFIA system (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Cytokines ELISAs of mTNF, IL-6 and mCXCL1 concentrations were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D). ELISA kits were as follows: Human IL-17A Duoset ELISA (DY317), Human IL-21 Duoset ELISA (DY782), Human IL-6 Duoset ELISA (DY206), Human IL-8 Duoset ELISA (DY208), Human TNFα Duoset ELISA (DY210), Mouse CXCL1/KC Duoset ELISA (DY453), Mouse IL-6 Duoset ELISA (DY406) and Mouse TNFα Duoset ELISA (DY410) (all from R&D Systems); Mouse Ig2b -HRP (ELISA) (A90-109P), Mouse IgG1 -HRP (ELISA) (A90-105P), Mouse IgG2c ELISA Quantification set (E90-136), Mouse IgG3-HRP (ELISA) (A90-111P), Mouse IgM -HRP (ELISA) (A90-101P) (all from Bethyl Laboratories).

Detection of high-affinity IgG antibodies

Mice were immunized intra-peritoneally with 100 μg alum-precipitated (Thermo Scientific) 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP) coupled to chicken γ-globulin (NP-CGG), with a ratio of NP to CGG of 21 (BioSearch Technologies). NP-specific antibodies in the serum were measured by ELISA, using two different coupling ratios of NP–BSA (8 and 26) as the coating antigens. To estimate the affinity of NP-binding antibody, the ratio of NP8-binding antibody to NP26-binding antibody was calculated. In brief, Maxisorp plates (Nunc) were coated with 10 μg/ml NP-BSA in PBS at 4 °C overnight and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS. Serially diluted serum were then added and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, HRP-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (A90-105P; 1:1,000 dilution; Bethyl; Southern Biotech) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Between incubation steps, the plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. HRP activity was detected using TMB peroxidase substrate and stop solution (eBioscience). Absorbance was determined at 450 nm. As a standard, we used serum pooled from immunized mice, which was applied to every plate.

Generation of bead arrays

NeutrAvidin (Thermo Fischer) was coupled with carboxylated beads (COOH Microspheres, Luminex-Corp.) in accordance to previously published antigen coupling protocols with minor modifications34. In brief, 1 × 106 beads per bead identity were distributed across 96-well plates (Greiner BioOne), washed and re-suspended in phosphate buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, pH 6.2) using a plate magnet and a plate washer (EL406, Biotek). The carboxyl groups on the surface of the beads were activated by 0.5 mg of 1-ethyl-3(3-dimethylamino-propyl) carbodiimide (Pierce) and 0.5 mg of N-hydroxysuccinimide (Pierce) in 100 μl phosphate buffer. After 20 min of incubation on a shaker (Grant Bio), beads were washed in MES buffer (0.05 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.0). 250 μg/ml of NeutraAvidin was prepared in MES buffer and added to the beads. The coupling reaction was allowed to take place for 2 h at room temperature (RT), the beads were then washed three times in PBS-T (0.05% Tween20 in PBS), re-suspended in 100 μl storage buffer (1% BSA, 0.05% Tween20 and ProClin300 in PBS) and stored in plates at 4 °C overnight. The next day, 100 μl of each different biotinylated peptide at 50 μM concentration was added to neutravidin-coated beads. Following an overnight incubation at 4 °C, beads were washed three times in PBS-T and re-suspended in 100 μl storage buffer. The final antigen-suspension bead array was prepared by combining equal volumes of each bead identity. Triple helical CII peptides containing defined epitopes have previously been described35. Immobilization of the peptides was confirmed by the use of CII-epitope-specific monoclonal antibodies used in collagen-antibody-induced arthritis (data not shown).

Assay on suspension arrays

Serum samples were diluted 1:100 (v/v) in assay buffer (3% BSA, 5% milk powder, 0,1% ProClin300, 0,05% Tween 20 and 100 ug/mL Neutravidin in PBS) and incubated for 60 min at RT on a shaker for pre-adsorption of unspecific antibodies. Using a liquid handler (CyBi-SELMA, CyBio), 45 μl of 1:100 diluted serum samples were transferred to a 384 well plate containing 5 μl bead array per well. Following incubation at RT on a shaker (Grant Bio) for 75 min, beads were washed six times with 60 μl PBS-T on a plate washer (EL406, Biotek) and re-suspended in 50 μl of each secondary antibody solution. Anti-mouse IgG Fcy–PE diluted 1:500 in a buffer consisting of 5% BSA, 0.05% Tween20 in PBS was used for detection of antibodies. After incubation with the secondary antibodies for 40 min, the beads were washed three times with 60 μl PBS-T and re-suspended in 60 μl PBS-T for measurement by a FlexMap3D instrument (Luminex Corp.). The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was chosen to display serum antibody-peptide interactions. Antibodies were as follows: RORγt: Q31-378, 1:200; St6gal1 (C) 18985, 1:100, IBL; rabbit IgG, F0313, 1:400, Biotechnology; IL-17A, 1:200; OVA-A488. 1:400.

Cell preparation and flow cytometry

For flow cytometry, bone marrow, inguinal lymph nodes, spleens and paws were isolated. For single-cell isolation, paws were further digested for 1 h at 37 °C with collagenase D. Afterward, cells were stained for surface markers. If intracellular staining was done, cells were then fixed and permeabilized with the Foxp3 staining Kit (eBioscience) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For intracellular cytokine analysis, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13 acetate and ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h; monensin (BD-Bioscience) and brefeldin A (BioLegend) were added after 2 h. All flow cytometric analysis was performed on a Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and evaluated using the FlowJo or the Kaluza Flow Cytometry analysis software (Beckman Coulter).

Antibodies

The following fluorochrome- or biotin-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies and reagents were used (all at a dilution of 1:400 unless stated otherwise): anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-CD19 (6D5), anti-CD25 (PC61), anti-CD45R (RA3-6B2), anti-CD138 (281-2), anti-CD267 (8F10), anti-GR-1(RB6-8C5), anti-IL4(11B11), anti-IL-17A (1:200; TC11-18H10.1), anti-Foxp3 (MF-14), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2) and anti-PD-1 (MH5A) (all from BioLegend); anti-IL22Ra1 (clone 496514) (from R&D Systems); anti-RORγt (1:200; Q31-378) (from BD Bioscience); anti-St6gal1 (C) (18985; 1:100; from IBL); and normal rabbit IgG (isotype-matched control antibody Biotechnology (F0313)) (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). OVA-specific plasma cells were stained intracellularly with intracellularly OVA-A488 ordered by Thermo-Fisher.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stained with anti-CD19 (130-091-248; 1:20; Miltenyi Biotech), anti-CD27 (clone MT271 (RUO); 1:40; BD) and anti-CD38 (551400; 1:100; BD). Surface sialic acid was stained with SNA–fluorescein-isothiocyanate (VEC-FL-1301; 1:400) from Vector Laboratory.

For cytokine-blocking experiments and TH17 differentiation, the following antibodies were used: anti-mouse CD3 (145-2C11), anti-mouse CD28 (37.51), anti-mouse GM-CSF (MP-22E9), anti-mouse IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1), anti-mouse/human IL21 (7H20-I19-M3) and anti-mouse IL22 (clone BL35175) (all from BioLegend).

B cell isolation

CD43− splenic B cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice by CD43 depletion using MACS technology (Miltenyi).

CD138+CD19+B220−CD3−GR1− plasma cells were sorted out using the spleens of Il23a−/− and C57BL/6j mice before and during the induction of the CIA (Supplementary Fig. 2) using a MoFlo XDP cell sorter (Beckman Coulter).

PBMC isolation

PBMCs were separated from healthy donors by Ficoll-Diatrizoate density-gradient centrifugation (Bio-Rad). After centrifugation, the PBMC-containing interphase was isolated and washed two times with 1 mM EDTA in PBS.

For SNA-lectin based flow cytometry, PBMCs were stained untreated or, as a negative control, were digested with neuraminidase (100 mU, 1 h at 37 °C), or sialic acid was oxidized using mild iodate treatment (2 mM in PBS).

Monocyte-derived dendritic cell (MoDC) differentiation

MoDCs were differentiated from monocytes isolated from PBMCs (via their ability to bind to plastic surfaces) and were cultivated in RPMI supplemented with 5% FCS (Biochrom), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), 1% l-glutamine (Gibco) 1 mM HEPES and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma) in the presence of 800 U/ml GM-CSF (Peprotech) and 500 U/ml IL-4 (Peprotech). Cells were fed on day 3 and day 5. Experiments were performed on day 6 by co-incubation of MoDCs with heat-aggregated ICs after pre-conditioning of MoDCs with 0.5 ng/ml LPS.

T cell skewing and co cultures

Mouse splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated using EasySep (STEMCELL Technologies). TH17 cells were differentiated with plate-bound 5 μg/ml anti-CD3 (100214; BioLegend) and IMDM medium (Lonza) supplemented with 3 μg/ml anti-CD28 (102111; BioLegend) and IL6 (10 ng/ml) and TGF-β (5 ng/ml, BioLegend), and for the pathogenic TH17 cells, they were differentiated in the presence of IL6 (10 ng/ml, BioLegend) and IL-23 (20 ng/ml, R&D Systems). After 4 d of culture, T cells were collected and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) plus monensin (BD Biosciences) for intracellular cytokine staining.

For assays of TH17 cell–mediated St6gal1 regulation in B cells, MACS-enriched B cells were stimulated with LPS (5 μg/ml) and cultured together with TH17 cells at a ratio of 2:1 in appropriate B cell medium. Blocking antibodies were purchased from BioLegend and used at a concentration of 2 mg/ml (anti-IL-17, TC11.18H1C1; anti-IL-21, 7H20I19-M3; anti-IL-22, Poly5164; anti-GM-CSF, MPA-22E9). After 72 h of culture, B cells were either sorted for RNA-isolation or analyzed via flow cytometry.

IgG isolation

Human IgG was obtained from healthy control subjects, asymptomatic ACPA+ subjects that had not experienced arthritis yet and from ACPA+ patients with active RA (clinical disease activity score, 28 3.2).

Mouse IgG was obtained from arthritic K/BxN, C57BL/6 (Charles River), DBA/1 or Il23a−/− mice on day 50 after immunization.

IgG was isolated by purification over a protein G column (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Collagen-specific IgG was isolated via chicken type II collagen bound on CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B (Sigma).

In vitro IgG modification

For desialylation, 1 mg of human or mouse IgG was incubated with 100 U or 200 U neuraminidase (NEB) for 24 h or 48 h, respectively, at 37 °C.

The efficiency of the enzymatic digestion was tested via lectin blot. Protein concentration was determined with NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific).

For galactosylation, 1 mg of mouse IgG was incubated with 0.8 mM UDP-galactose (Calbiochem) and 50 mU of β-1-4 galactosyl transferase (Sigma) in 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, with 20 mM MnCl2 for 48 h at 37 °C. For subsequent sialylation, 1 mg of IgG was incubated with 0.5 mM CMP-sialic acid (Calbiochem) and 25 mU of α2-6 sialyl transferase (Sigma) in 50 mM MES, pH 6,0 with 20 mM MnCl2 for 48 h at 37 °C. The reactions were confirmed with a lectin blot.

Fc-glycosylation analysis of IgG isolated from Il23a−/− and wild-type mice

For the analysis of Fc-glycans, the IgG eluates were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and subjected to tryptic digestion by adding 200 ng trypsin (sequencing grade, Promega) in 40 μl ammonium bicarbonate buffer followed by overnight incubation at 37 °C. Digested IgG from Il23a−/− and wild-type mice were separated and analyzed on an Ultimate 3000 UPLC system (Dionex Corporation, USA) coupled to a maXis HD Ultra-High Resolution Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) as described previously with minor modifications36,37. Following extraction of tryptic glycopeptides by a C18 solid-phase extraction-trap column (Dionex Acclaim PepMap100), separation was achieved on an Ascentis Express C18 nano-liquid chromatography (LC) column (Supelco, USA) conditioned at 900 nl/min with 0.1% TFA (mobile phase A) after which the following gradient of mobile phase A and 95% acetonitrile (mobile phase B) was applied: 0 min 3% B, 2 min 6% B, 4.5 min 18% B, 5 min 30% B, 7 min 30% B, 8 min 0% B and 11 min 0% B. The UPLC was interfaced to the mass spectrometer with a sheath-flow ESI sprayer. Mass spectra were recorded from m/z 600 to 2,000 with two averages at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. Quadrupole ion energy and collision energy of the mass spectrometer were set at 2 eV and 4 eV, respectively. The total analysis time per sample was 13 min. Quality of mass spectra was evaluated based on intensities of total IgG1 glycoforms. Data processing and calculations of the level of galactosylation, sialylation, and fucosylation residues of IgG1and IgG2 were performed as described earlier38.

BMDC stimulation and assessment of IC activity

For measuring the intrinsic inflammatory capacity of mouse total and collagen type II specific IgG antibodies, bone-marrow cells were isolated from femora and tibiae of 6- to 8-week-old mice. Cell populations depleted of erythrocytes were seeded in R10 medium at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish (Falcon, no. 1029, bacterial quality) R10 culture medium is composed of RPMI 1640 (Lonza) supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml, Lonza), streptomycin (100 mg/ml, Lonza), l-glutamine (2 mM, Lonza), 2-mercaptoethanol (50 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (PAA Laboratories). GM-CSF supernatant (1:10) from a cell line transfected with the gene encoding mouse GM-CSF was used39. Medium was changed every 3 d. On day 8, non-adherent cells (>95% CD11c+) were harvested and used for the different experiments40.

For IC-activity analysis, total-IgG ICs were obtained by heat aggregation at 63 °C for 30min. CII-specific IgG complexes were generated through immobilization on CII-coated plates.

IgG activity was analyzed by co-incubation with mouse BMDCs and human moDCs. Pro-inflammatory cytokines were measured after 24 h. Equality of CII-specific IgG concentrations was checked by ELISA of total IgG after the experiments were completed.

Immunofluorescence

Spleens from mice were collected, embedded in Tissue-Tek (4583 BioLab) and snap-frozen on dry ice. Frozen sections (thickness, 5 μm) were fixed in acetone. Before staining, sections were blocked with 5% rat serum for 30 min. Possible biotin- or streptavidin-binding sites were blocked using the Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit from Vector. Afterward, the sections were stained with various antibodies. The following fluorochrome- or biotin-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies and reagents were used: anti-CD3 (17A2; 1:50), anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1; 1:20), anti-RORγt (B2D; 1:20), anti-IgD (11-26c-2a; 1:50), rat IgG1 isotype-matched control antibody (RTK2071) and rat IgG2a isotype (RTK2758) (all from BioLegend); and anti-CD21/35(8D9; 1:50) (from eBioscience). Sections were mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Dako) and analyzed with an Eclipse-80i microscope (Nikon). Pictures are presented with pseudocolors (as indicated in figures) by NIS elements software BR3.0 (Nikon).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as previously described41. The gene-expression values were normalized to those of the control gene encoding β-actin.

The following oligonucleotides were used: b4galt1, 5′-GCCATCAATGGATTCCCTAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATTTGGACGTGATATAGACAT GC-3′ (antisense); st6gal1, 5′-TGAGCCTTCCCCAAATACCT-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTCACAGGATGATCAAAAACCA-3′ (antisense); il22ra1 5′-GCACACTACCATCAAACCGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAAGGTGCATCTGGTAGGTGT-3′ (antisense); alpha-actin, 5′-TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCCTAGA-3′ (antisense).

Human subjects

Informed consent was obtained from all healthy control subjects and all patients with RA. Analysis of human material was approved by the ethics committee of the University hospital Erlangen.

Statistics

All in vitro experiments were performed using three different biological replicates at least three independent times. For the in vivo studies relying on the preventive protocol, 5–10 mice were used for each experimental or control group and analyses were repeated at least twice. For the curative protocol, we used five mice for each experimental or control group.

Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired Student’s t-test or by ordinary one-way ANOVA. Outliers were eliminated using the Grubbs test. All the analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism TM 6 software (Graphpad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Supplementary Material

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Stoll, A. Klej and U. Appelt for technical assistance; Boehringer-Ingelheim for the fully mouse antibody to mouse IL-23p19; MD Bioscience for the collagen-antibody-induced arthritis ‘cocktail’; and K. Ralph, D. Souza and G. Nabozny (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals) for technical advice and monoclonal antibody to anti-IL23. Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CRC1181 to G.K., G.S., F.N., C.B. and D.D.; SPP1468-IMMUNOBONE to G.K., G.S. and F.N.; and CRC643 to G.S., F.N. and D.D.), the European Union (ERC StG 640087 – SOS to G.K.; MASTERSWITCH project to G.S.; and BTCure to G.S. and C.B.), the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research, Erlangen (IZKF A55 to G.K.; and A68 to G.K. and F.N.), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (METARTHROS to G.K. and G.S.), the Else-Kröner Fresenius Stiftung (2013_A274 to G.K.), the ELAN Fonds of the Universitätsklinikum Erlangen (14-10-17-1 to G.H.), the Strategic Science Foundation (R.H.), the KAWallenberg Fondation (R.H.) and the Bavarian Genome Network (BayGene to D.D.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

R.P. designed the study, performed and interpreted experiments and wrote the manuscript; T.R., N.I., S.C., U.H., J.A.A., M.S., B.H. and P.D. performed experiments and collected and interpreted the data; H.U.S, R.T., T.H.W. and R.H. provided help during the design of the study and wrote the manuscript; A.K., S.U. and A.J.H. designed the study and experiments and interpreted data; G.F.H., C.G., S.Bö., A.L., I.M., K.S.N. and E.L. measured samples and interpreted the data; C.B. was involved in the generation of Il23a−/− mice and provided input; W.S. and D.D. provided expertise and input and wrote the manuscript; M.W., Y.R. and C.A.K. measured and interpreted the glycostructure of IgG; M.H., S Bl., F.N., G.S. and G.K. designed the study and experiments and wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2205–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji H, et al. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant EP, et al. Essential role for the C5a receptor in regulating the effector phase of synovial infiltration and joint destruction in experimental arthritis. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1461–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinau S, Martinsson P, Heyman B. Induction and suppression of collagen-induced arthritis is dependent on distinct Fcγ receptors. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1611–1616. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svensson L, Jirholt J, Holmdahl R, Jansson L. B cell-deficient mice do not develop type II collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:521–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto I, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition of a glycolytic enzyme. Science. 1999;286:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmdahl R, Rubin K, Klareskog L, Larsson E, Wigzell H. Characterization of the antibody response in mice with type II collagen-induced arthritis, using monoclonal anti-type II collagen antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:400–410. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Venrooij WJ, van Beers JJ, Pruijn GJ. Anti-CCP antibodies: the past, the present and the future. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:391–398. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renato GM. B cell depletion in early rheumatoid arthritis: a new concept in therapeutics. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1173:729–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2741–2749. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berglin E, et al. A combination of autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and HLA-DRB1 locus antigens is strongly associated with future onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R303–R308. doi: 10.1186/ar1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiozawa K, et al. Anticitrullinated protein antibody, but not its titer, is a predictor of radiographic progression and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:694–700. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ursum J, Bos WH, van Dillen N, Dijkmans BA, van Schaardenburg D. Levels of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and IgM rheumatoid factor are not associated with outcome in early arthritis patients: a cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R8. doi: 10.1186/ar2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubberts E. The IL-23-IL-17 axis in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:425–429. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leipe J, et al. Role of Th17 cells in human autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2876–2885. doi: 10.1002/art.27622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy CA, et al. Divergent pro- and antiinflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1951–1957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada H, et al. Th1 but not Th17 cells predominate in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1299–1304. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pöllinger B. IL-17 producing T cells in mouse models of multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Mol Med. 2012;90:613–624. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0841-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigall VM, Panayi GS. Autoantigens and immune pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22:281–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Antibody-mediated modulation of immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony RM, et al. Recapitulation of IVIG anti-inflammatory activity with a recombinant IgG Fc. Science. 2008;320:373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1154315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornelissen F, et al. IL-23 dependent and independent stages of experimental arthritis: no clinical effect of therapeutic IL-23p19 inhibition in collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsdoerffer M, et al. Proinflammatory T helper type 17 cells are effective B-cell helpers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14292–14297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009234107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirota K, et al. Plasticity of TH17 cells in Peyer’s patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:372–379. doi: 10.1038/ni.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu HC, et al. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:166–175. doi: 10.1038/ni1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu HJ, et al. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherer HU, et al. Glycan profiling of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies isolated from human serum and synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1620–1629. doi: 10.1002/art.27414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rombouts Y, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies acquire a pro-inflammatory Fc glycosylation phenotype prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:234–241. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oefner CM, et al. Tolerance induction with T cell-dependent protein antigens induces regulatory sialylated IgGs. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012;129:1647–1655 e1613. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess C, et al. T cell-independent B cell activation induces immunosuppressive sialylated IgG antibodies. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3788–3796. doi: 10.1172/JCI65938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genovese MC, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a phase II, dose-finding, double-blind, randomised, placebo controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:863–869. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker C, et al. Cutting edge: IL-23 cross-regulates IL-12 production in T cell-dependent experimental colitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:2760–2764. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nandakumar KS, Holmdahl R. Efficient promotion of collagen antibody induced arthritis (CAIA) using four monoclonal antibodies specific for the major epitopes recognized in both collagen induced arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol Methods. 2005;304:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayoglu B, et al. Autoantibody profiling in multiple sclerosis using arrays of human protein fragments. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2657–2672. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.026757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindh I, et al. Type II collagen antibody response is enriched in the synovial fluid of rheumatoid joints and directed to the same major epitopes as in collagen induced arthritis in primates and mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R143. doi: 10.1186/ar4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harre U, et al. Glycosylation of immunoglobulin G determines osteoclast differentiation and bone loss. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6651. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rombouts Y, et al. Extensive glycosylation of ACPAs-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75:578–585. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selman MH, et al. Fc specific IgG glycosylation profiling by robust nano-reverse phase HPLC-MS using a sheath-flow ESI sprayer interface. J Proteomics. 2012;75:1318–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zal T, Volkmann A, Stockinger B. Mechanisms of tolerance induction in major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted T cells specific for a blood-borne self-antigen. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2089–2099. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutz MB, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krönke G, et al. Oxidized phospholipids induce expression of human heme oxygenase-1 involving activation of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51006–51014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.