Abstract

Divergent life or death responses of a cell can be controlled by a single cytokine (tumor necrosis factor α, TNF) via the signaling pathways that respond to activation of its two receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2). Here, we show that the choice of life or death can be controlled by manipulation of TNFR signals. In human erythroleukemia patient myeloid progenitor stem cells (TF-1) as well as chronic myelogenous leukemia cells (K562), granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor primes cells for apoptosis. These death-responsive cells show prolonged TNF stimulation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, but no NF-κB transcriptional activity as a consequence of receptor-interacting protein degradation by caspases. Conversely, cells of a proliferative phenotype display antiapoptotic NF-κB responses that antagonize c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase stress kinase effects. These proliferative effects of TNF are apparently due to enhanced basal expression of the caspase-8/FLICE-inhibitory protein FLIP. Manipulation of the NF-κB, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signals switches leukemia cells from a proliferative to an apoptotic phenotype; consequently, these highly proliferative cells die rapidly. In addition, sodium salicylate mimics the death phenotype signals and causes selective destruction of leukemia cells. These findings reveal the signaling mechanisms underlying the phenomenon of human leukemia cell life/death switching. Additionally, through knowledge of the signals that control TNF life/death switching, we have identified several therapeutic targets for selectively killing these cells.

Understanding the signals controlling cell proliferation or apoptosis is vital to understanding and controlling diseases such as cancer. Most cells have the ability to proliferate or die dependent on their environment and the controlling signals they encounter. One signal that has the capacity to cause either cellular proliferation or cell death is tumor necrosis factor α (TNF). TNF binds two cell-surface receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, to generate the plethora of the cytokine's cellular actions (1, 2). Much effort has gone into understanding the means by which TNFRs can control a cell's response. However, the mechanism by which this decision between cell death or survival or proliferation is made is not known.

TNFR subtypes TNFR1 and TNFR2 initiate their actions by the binding of TNFR-associating factors (TRAFs) and activating extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the related stress kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK (1, 2). TRAF-2 and the receptor-interacting protein (RIP) adaptor protein bind to activated TNFRs and mediate stimulation of JNK and NF-κB (3–7). JNK and p38 MAPK pathways can also be stimulated by TNF through apoptosis signal-regulated kinase and germinal center kinase (8–10). The caspase-8/FLICE inhibitor protein (FLIP) has the ability to block caspase function and regulate NF-κB and ERK pathway signaling (11, 12). However, the cellular mechanisms by which this pleiotropic cytokine directs cell fate are a source of much research endeavor.

Here, we show in the same cell, the signaling machinery necessary to switch a human leukemia cell from a proliferative to an apoptotic phenotype (TNF life/death switching). Sustained TNF-induced NF-κB signaling and transcription allow the cell to survive and proliferate. Converting the cells into a death phenotype, one then observes reduced basal levels of FLIP, allowing caspase-mediated degradation of RIP that switches the protective NF-κB pathway off, resulting in TNF-driven stimulation of proapoptotic pathways such as sustained JNK and p38 MAPK activity. This FLIP-inhibited RIP degradation switch tips the balance from sustained NF-κB transcription to the antagonistic activities of JNK and p38 MAPK that support the apoptotic destruction of the cell by its TNF stimulus.

Methods

Materials. TF-1 human erythroleukemia cells (13) and K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Salisbury, U.K.), whereas MOLT-4 acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells and HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells were kindly donated by Heather Wallace (University of Aberdeen). Recombinant human TNF was purchased from R&D Systems. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was a kind gift from Meenu Wadhwa (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, Potters Bar, U.K.). Phosphospecific JNK, p38 MAPK, and p42/p44 MAPK monoclonal antisera (as detailed in ref. 14) were purchased from New England Biolabs. RIP monoclonal antibody was bought from Pierce. Anti-FLIP rat monoclonal antibody (Dave II) and FLIP polyclonal antiserum were purchased from Alexis Biochemicals and R&D Systems, respectively. MR1–2 and MR2–1 TNFR1 and TNFR2 agonistic antisera (14) were a gift from Wim Buurman (University of Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands). All other antisera were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. NF-κB inhibitory retroviruses were a gift from David Kluth (University of Aberdeen), and the SEK-AL dominant negative cDNA construct was kindly provided by Jim Woodget (University of Toronto, Toronto). The hrGFP-linked reporter constructs were purchased from Stratagene. PD98059, SB203580, and SP600125 were procured from Calbiochem. Geldanamycin was obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich.

Proliferation/Death Assays. Human TF-1 cells or were preincubated for 16 h in the presence or absence of 1 ng/ml GM-CSF before the indicated combinations of treatments. After treatment, cell number was measured by incubation with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) one-solution assay reagent (Promega) at 37°C for 1 h before reading absorbance in quadruplicate at 490 nm. Live/dead TF-1 cell measurement was performed by incubation of treated cells for 1 h in the dark with 1 μM calcein-AM (which cleaves and loads into living cells only). Samples were then washed once and stained with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide, a cell-impermeant nuclear stain that stains only dead cell condensed nuclei. Measurement of green versus red fluorescence indicates the proliferating/healthy or dead cells, respectively.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis. After 16 h of incubation with or without 1 ng/ml GM-CSF, human TF-1 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml TNF, before labeling with propidium iodide and analysis using flow cytometry (14).

SDS/PAGE and Western Blotting. An initial 16-h incubation of human TF-1 cells with or without 1 ng/ml GM-CSF differentiated samples into death or life phenotypes, respectively. Cells were then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for the indicated time periods before total protein extraction by using the RIPA buffer method (15). After SDS/PAGE separation, protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and Western analyses were performed with the indicated antisera according to manufacturers' instructions. All cell lines were treated in a similar manner for Western analysis.

Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift/Supershift Assays. Measurement of NF-κB oligonucleotide binding to activated transcription factor was performed as described (16). Supershift assays were performed in the additional presence of specific NF-κB subunit antisera purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Reporter Construct Analysis. Human TF-1 cells were transfected by using Nucleofection technology (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany) program T-03, with cells suspended in Nucleofection solution V. Transfections introduced Stratagene's specific ERK-responsive trans-activating reporter construct systems into cells. This allowed hrGFP report to be observed in response to stimulation of the JNK (c-Jun), p38 MAPK (CHOP), or p42/p44 MAPK (Elk-1) kinase pathways. pFR-hrGFP cDNA (2.5 μg) was cotransfected with 150 ng of pFA-c-Jun, 150 ng of pFA-Elk-1, or 2.5 ng of pFA-CHOP dependent on the pathway intended for study. Alternatively, cells were transfected as above with the single NF-κB-responsive GFP-linked reporter construct (NF-κB-hrGFP; ref. 16) from Stratagene (2.5 μg). After transfection, TF-1 cells were incubated for 16 h with or without 1 ng/ml GM-CSF before application of indicated inhibitors and/or treatments. PD98059 (MEK1/p42/44 MAPK inhibitor) and SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), both at 30 μM, SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) at 5 μM, emodin (NF-κB inhibitor) at 30 μg/ml, and sodium salicylate at 5 mM were all applied 1 h before 50 ng/ml TNF treatment. Selected TF-1 cell samples were infected with 25 plaque-forming units/ml Adv-IκB-α or Adv-p65RHD (adenoviral NF-κB inhibitors) 24 h before transfection. Subsequent construct activation was assessed by quantification of hrGFP expression over 48 h by using fluorescence microscopy (16).

Results and Discussion

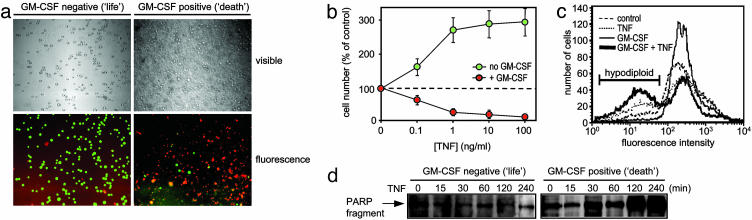

GM-CSF Controls Life/Death Switching. To understand the mechanisms that control TNF-induced proliferation or death in human leukemia cells, we used CD34+ erythroleukemia cells (TF-1; ref. 13) shown previously to respond to TNF either by proliferating or, if the cell is mitotic, by dying through rapid apoptosis (17). As an apoptotic phenotype was associated with increased TNFR2 expression (17), and as GM-CSF increased TNFR2 expression without altering TNFR1 levels (data not shown), we investigated the ability of GM-CSF to convert TF-1 cells from the TNF-responsive proliferative (life) phenotype into the apoptotic (death) one. Low-dose GM-CSF pretreatment changed TNF from a proliferative into an apoptotic signal (Fig. 1 a and b). As was observed during TF-1 cell mitosis (17), GM-CSF pretreatment did not alter TNFR1 levels but markedly increased TNFR2 expression (data not shown), resulting in TNF-induced death rather than proliferation. This life/death switching ability of GM-CSF is both time and concentration dependent and also is achieved by interleukin-3 with similar kinetics but with less efficacy (data not shown). GM-CSF switching between the life and death phenotypes showed proliferation and classic markers of apoptotic cell death such as hypodiploid fragmented DNA (Fig. 1c) and caspase cleavage of the DNA repair enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

TNF-induced life/death switching in TF-1 cells by GM-CSF. TF-1 human leukemia cells were preincubated for 16 h with or without 1 ng/ml GM-CSF as indicated before treatment for 24 h with the indicated concentration of recombinant human TNF. (a) Cells were loaded with calcein-AM and propidium iodide as described in Methods to stain live (green) and dead (red) cells, respectively. (×100.) (b) Cell number was then assessed by MTS assay as described in Methods. Mean values ± SD of quadruplicate determinations from a representative experiment repeated at least four separate times are shown. (c) TF-1 cells pretreated with GM-CSF as in a and then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for 8 h before propidium iodide cell-cycle analysis using flow cytometry. (d) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage measured by Western analysis of cells pretreated with 1 ng/ml GM-CSF for 16 h, then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for the indicated time. Data from a representative experiment of at least three independent determinations are shown.

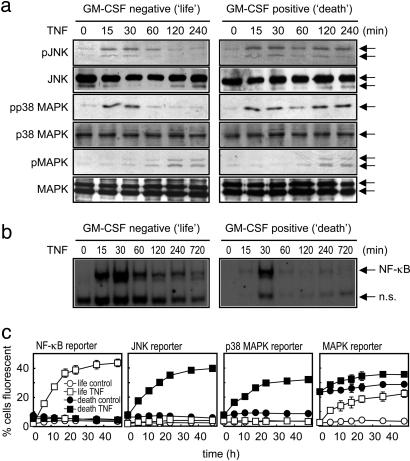

Role of JNK, p38 MAPK, and NF-κB in Life/Death Switching. To understand the TNFR signaling responsible for the life/death switching phenomenon in leukemia cells, we analyzed TNFR-associated signaling in the life and death phenotypes (Fig. 2). TNF receptors conduct many of their cellular effects through the activation of the ERK families MAPK, p38 MAPK, and JNK (18), as well as the NF-κB transcription factor (19). Because p38 MAPK and JNK stress kinases have been described as proapoptotic (8, 20, 21), we ascertained the ability of TNF to evoke p38 MAPK, JNK, and MAPK activity in life and death TF-1 phenotypes (Fig. 2a). In the life phenotype, transient TNF-induced p38 MAPK and JNK stimulation was observed; however, these short-lived kinase activations were not sufficient to create p38 MAPK- or JNK-evoked transcriptional activity, as judged by distinct reporter construct assays (Fig. 2c). Conversely, TNF induced a prolonged stimulation of p38 MAPK and JNK in the death phenotype (Fig. 2a), which consequently resulted in transcription (Fig. 2c). In the death phenotype, such sustained activity of p38 MAPK and JNK was due to less deactivation by their inhibitory phosphatases (18). Stimulation of TNF-driven MAPK function was not differentially activated between life and death phenotypes (Fig. 2a). The GM-CSF pretreatment itself stimulated MAPK activity (22), leading to higher observable MAPK-mediated transcription (Fig. 2c). TNF stimulation of MAPK activity was apparent in both life and death phenotypes with similar kinetics of TNF excitation (Fig. 2 a and c). Thus, unlike p38 MAPK and JNK, MAPK is not involved in the TNF life/death switching phenomenon. The differential behavior of TNF on sustained p38 MAPK or JNK activation and their subsequent transcriptional activity in death-responsive cells only is opposite to the observed response seen with NF-κB (Fig. 2b). The life phenotype cells show strong sustained stimulation of NF-κB by TNF, whereas NF-κB activation in the death phenotype is exceptionally brief and does not result in TNF-stimulated NF-κB transcription, as measured by reporter construct (Fig. 2c). These findings agree with previous reports that describe antiapoptotic NF-κB (23) as antagonistic to apoptotic JNK (24).

Fig. 2.

Sustained ERK signaling mediates TNF-induced life/death switching. (a) Western analysis of TF-1 cells pretreated with GM-CSF as in Fig. 1, then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for the indicated time before analysis of JNK, p38 MAPK, and MAPK activity by using phosphospecific antisera (Upper); total protein was measured by pan-antisera (Lower). Representative blots of at least four separate experiments are shown. (b) NF-κB electrophoretic mobilityshift assay of TF-1 cells treated with GM-CSF and/or TNF as described for a. n.s., Nonspecific band. (c) Reporter construct analysis of sustained ERK activity in TF-1 life or death cells treated as described above and measured as outlined in Methods. Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 4.

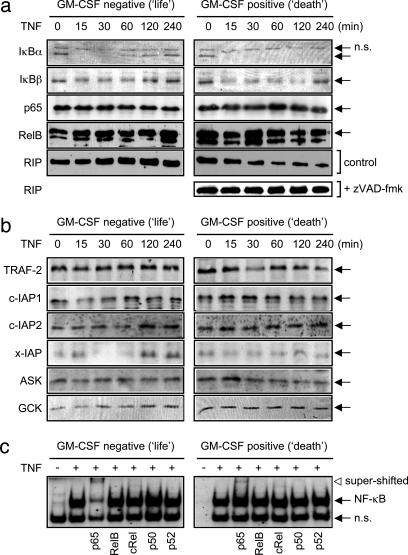

Some NF-κB activation cascades have been shown to be mediated by RIP and/or TRAF-2, with the caspase-cleaved product inhibiting stimulus-induced NF-κB activity (25). We therefore determined the ability of TNF to stimulate such NF-κB signaling in life and death TF-1 cells and found transient IκB-α and IκB-β degradation in the life phenotype, but sustained IκB-α and IκB-β degradation in death cells (Fig. 3a). IκB-α resynthesis, an NF-κB-dependent process (26), occurred in life but not death TF-1 cells, additionally supporting a lack of TNF-evoked NF-κB action in the death phenotype (Fig. 2b). The total levels of p65 subunit of NF-κB and RelB proteins were unaltered in the life/death settings or by TNF treatment. Basal RIP levels were similar in life and death cells, but TNF induced the degradation of RIP in the death cells only (Fig. 3a). This TNF-induced RIP degradation was mediated by caspases, as its cleavage was blocked by the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. Such TNF-evoked caspase action occurred in death cells only, with no TNF-induced caspase activity observed in life cells (Fig. 1c). Therefore, degradation of RIP blocked TNF-induced NF-κB activation in the death phenotype. The adaptor proteins TRAF-2 and RIP lead to the activation of p38 MAPK, JNK, and NF-κB (2). Both active TNFR1 and TNFR2 bind TRAF-2 and RIP adaptor protein to mediate their cellular actions; thus, we further determined in TF-1 cells the signaling machinery associated with these mediator proteins. Western analysis revealed no difference in TRAF-1 or TRAF-2 levels in basal or TNF-treated life or death cells (data not shown and Fig. 3b). Although there was a small decrease in TRAF-2 levels in death cells, we did not consistently see any significant reduction in TRAF-2 stimulation either in TF-1 cells or in cells overexpressing TNFR2 (14), even though TRAF-2 degradation has been reported to be associated with TNFR2 signaling (27, 28) and TNFR2 levels are elevated in death phenotype TF-1 cells. Similarly, levels of the antiapoptotic adaptor proteins c-IAP1, c-IAP2, or x-IAP were consistently equal between life and death cell phenotypes; therefore, these proteins did not account for the signaling differences generating the TNF-life/death switching phenomenon. The upstream components of p38 MAPK and JNK activation by TNF (germinal center kinase and apoptosis signal-regulated kinase) were present in both life and death cell phenotypes with similar basal amounts (Fig. 3b) and were unchanged by TNF treatment. Therefore, as recently reported (29), adaptor protein machinery associated with TNFR1 did not appear to alter between death and nondeath cells, and it may be the later downstream signaling that consequently controls cell fate. Thus, switching of TF-1 cells from a life to death phenotype was not due to differences in TNFR-associated proteins but was a consequence of RIP degradation, cessation of NF-κB transcription, sustained p38 MAPK and JNK kinase function, and transcriptional activity.

Fig. 3.

Signaling machinery involved in TNF-induced life/death switching. (a and b) Western analysis of TF-1 cells pretreated with GM-CSF as in Fig. 1, then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for the indicated time. Where indicated, 10 μM zVAD-fmk (Z-Val-Ala-Asp(O-methyl)-fluoromethyl ketone) was preincubated for 1 h before TNF treatment. Representative blots of at least three separate experiments are shown. (c) Electrophoretic mobility-shift/supershift assay performed as outlined in Methods on TF-1 cells pretreated with 1 ng/ml GM-CSF for 16 h, then treated with 50 ng/ml TNF for 30 min (+) where shown. n.s., Nonspecific band.

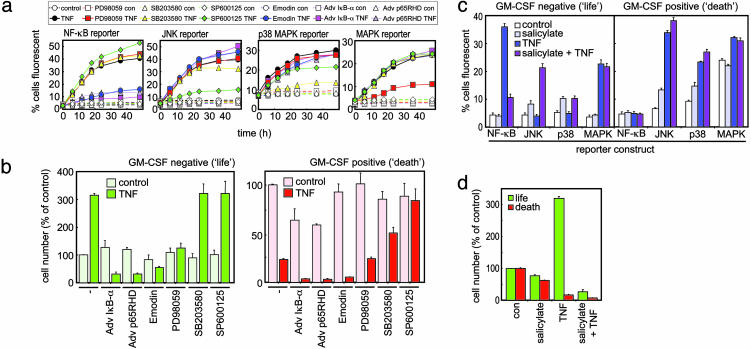

Switching Cells into a Death-Only Phenotype. To test our hypothesis that NF-κB, JNK, or p38 MAPK signaling controls the life/death switching phenomenon, we used pharmacological and molecular biological approaches. As only p65-p65 homodimers of NF-κB are activated in TF-1 cells by TNF, with RelB, cRel, p50, and p52 subunits remaining unstimulated (Fig. 3c), a p65-specific block should stop TNF-stimulated NF-κB activity. The specificity of our reporter construct system for its intended kinase target showed good selectivity judged by either pharmacological or dominant-negative manipulation (Fig. 4a). Use of the NF-κB inhibitor emodin, the dominant-negative IκB-α superrepressor, or p65RHD retrovirus blocked TNF-induced NF-κB activation and stimulated the death of TF-1 cells (Fig. 4 a and b). Interestingly, blocking NF-κB switched TNF from being a proliferative stimulus in life cells to an apoptotic one. In contrast, TNF's apoptotic effects in death cells were blocked by the inhibition of JNK activity by the specific inhibitor SP600125 (Fig. 4b) or SEK-AL dominant-negative cDNA construct (data not shown). These inhibitors of JNK showed >80% inhibition of TNF-stimulated JNK activation. TNF-mediated proliferation of life phenotype cells was unaffected by SP600125. The antiapoptotic ability of JNK blockade was also true of the selective p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 4b), further supporting an apoptotic role for sustained JNK- and p38 MAPK-mediated signaling, as outlined above.

Fig. 4.

Control of TNF life/death switching. (a) Reporter construct analysis of TNF-induced signaling in TF-1 cells pretreated with or without GM-CSF and modulated with the indicated inhibitors as described in Methods. Data represent the mean ± SEM, n = 4. con, Control. (b) MTS assays performed on TF-1 cells incubated in the presence or absence of GM-CSF and treated with a variety of inhibitors before TNF treatment. Results are calculated and expressed as a percentage of controls. Data illustrate the mean ± SEM, n = 4. (c) Reporter construct assessment of TF-1 cell signaling in cells after sodium salicylate treatment alone and in combination with TNF. TF-1 cells were previously differentiated into life or death phenotypes by preincubation in the presence or absence of GM-CSF. Results shown illustrate reporter construct activity 48 h after treatment. Data show the mean ± SEM, n = 4. (d) MTS assay carried out on TF-1 cells pretreated with or without GM-CSF before treatment with indicated ligands for 24 h. Data display the mean ± SEM, n = 4.

Salicylate Selectively Kills Leukemia Cells. Because sodium salicylate has been reported as a potent NF-κB inhibitor and potential anticancer agent (30, 31), we tested its effects on human leukemic cells. In life phenotype TF-1 cells, the normally prominent TNF-induced NF-κB activation was retarded by salicylate pretreatment (Fig. 4c). In contrast, salicylate stimulated JNK and p38 MAPK activity of either life or death phenotype cells, resulting in the programmed cell death of both phenotypes (Fig. 4 c and d). Thus, salicylate possessed p38 MAPK- and JNK-inducing activity as well as an NF-κB inhibitory function and allowed only the apoptotic, not the proliferative, nature of TNF to be exerted. Such a profile is highly advantageous for an antileukemic agent, as it promoted apoptotic pathways (p38 MAPK and JNK) while simultaneously inhibiting survival (NF-κB). Interestingly, like GM-CSF or blockade of NF-κB, salicylate switched TNF from being a potentially proliferative stimulus into a death-only signal. These strategies may also be useful in switching agents other than TNF into apoptotic signals in other types of leukemias or neoplastic diseases. Taken together, our data indicate that salicylate-induced death is more pronounced in cells displaying higher mitotic activity, such as proliferating leukemic blood cells. Salicylate may therefore predispose malignant cells to selective destruction and simultaneously prevent the death of quiescent, nonmalignant healthy blood cells, thus reducing many resultant systemic side effects.

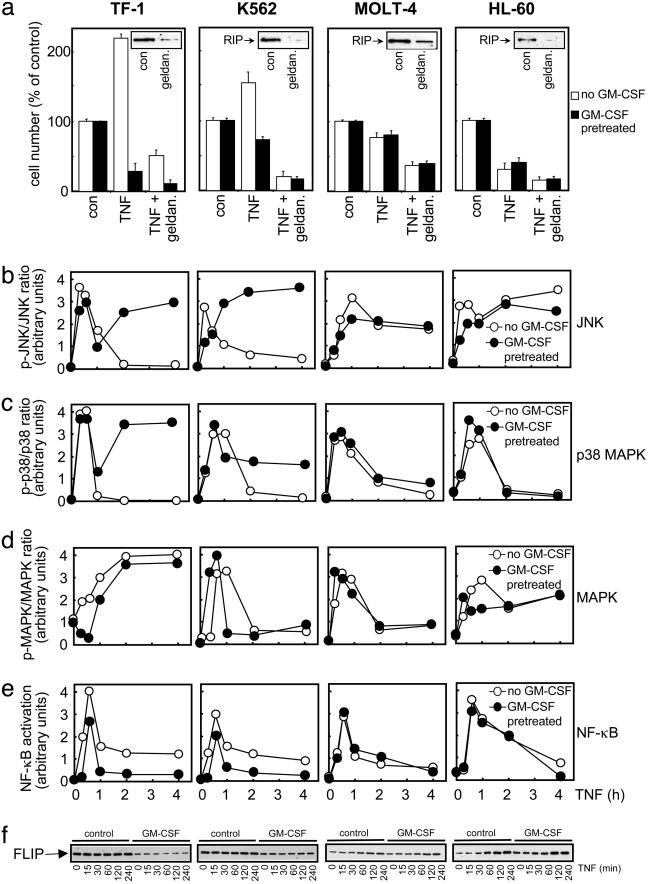

TNF Life/Death Switching in Other Leukemia Cells. To test whether the TNF life/death switching phenomenon was restricted to TF-1 cells, we measured the ability of TNF to cause proliferation or apoptosis in other human leukemia cell types. Although to a lesser extent than TF-1 cells, TNF causes proliferative and apoptotic responses also in K562 chronic myelogenous leukemia cells once again in a GM-CSF-dependent manner (Fig. 5a), thus proving that TNF life/death switching occurs in a variety of cells. However, MOLT-4 acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells and HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells respond to TNF by undergoing cell death only (Fig. 5a), serving as useful negative control cell lines. Interestingly, the induction of GM-CSF by TNF in TF-1 or K562 cells does not seem to be responsible per se for life/death switching. Even though GM-CSF causes the switching from a life to death phenotype in TF-1 and K562 cells, HL-60 cells also proliferate in response to GM-CSF, but only death responses occur to TNF (data not shown). Furthermore, although GM-CSF induced TNFR2 levels in TF-1 cells, the death responses seem to be mediated by TNFR1, as agonistic monoclonal antisera to TNFR1 (MR1–2) but not TNFR2 (MR2–1) are capable of mimicking TNF actions in TF-1, K562, MOLT-4, and HL-60 cells (data not shown). It is clear from these cells that the roles of JNK, p38 MAPK, and NF-κB in the TNF life/death switching observed in TF-1 cells are borne out in these other cell types, with only K562 cells showing differential JNK, p38 MAPK, and NF-κB signaling upon GM-CSF pretreatment (Fig. 5 b–e). Thus, these findings support a role for enhanced JNK/p38 MAPK and reduced NF-κB signaling in switching both TF-1 cells and K562 cell from a life to death phenotype.

Fig. 5.

TNF life/death switching in human leukemia cells. (a) The indicated human leukemia cells were preincubated for 16 h with or without 1 ng/ml GM-CSF as indicated before treatment for 24 h with 10 ng/ml recombinant human TNF before cell number was assessed by MTS assay, as described in Methods. Where shown, along with the GM-CSF treatment, cells were preincubated in combination with 1 μg/ml geldanamycin (geldan.). Mean values ± SD of quadruplicate determinations from a representative experiment repeated at least three separate times with similar findings are shown. (Inset) Western analysis of the RIP degradation in response to 1 μM geldanamycin treatment for 16 h. con, Control. (b–e) Cells were treated as described in Fig. 2 before analysis of ERK or NF-κB activity. Blots were scanned by a densitometer, and the ratio of phosphorylated to total protein was plotted as a time-course relationship. A representative result is shown of at least three separate experiments with similar findings. (f) Time course of TNF-stimulated cFLIP levels stimulated for the indicated time with 50 ng/ml TNF before Western analysis with a polyclonal anti-FLIP antiserum. Analysis with FLIP monoclonal antibody (Dave II) revealed no consistent processing or other forms of FLIP in these samples. The result shown is a representative blot from three separate experiments with similar conclusions.

A Role for FLIP in Leukemia Cell TNF Life/Death Switching. Not only does sodium salicylate direct TNF switching in TF-1 (Fig. 4) and K562 cells to death TNF responses only (<40% TNF-stimulated survival in both untreated and GM-CSF pretreatment K562 cells), but down-regulation of RIP allows only death TNF responses to prevail (Fig. 5a). Geldanamycin selectively downregulates RIP protein (32) in all four cell lines, which consequently blocks TNF-induced proliferative responses in TF-1 and K562 cells, allowing only TNF-induced apoptosis to be observed (Fig. 5a), thus supporting the importance of RIP degradation in TNF-induced apoptosis in life/death switching. Geldanamycin can also influence the function of FLIP protein (33), which prevents TNFR-mediated initiation of caspase-8 action (11) that is critical to the TNF-induced degradation of RIP. We therefore investigated whether cellular FLIP levels were altered in TNF life/death switching. Both TF-1 cell and K562 cells had significantly higher basal levels of FLIP in the life phenotype cells (Fig. 5f), which acts to block caspase activity (Figs. 1 and 3). Upon conversion of these cells to a death phenotype by GM-CSF pretreatment, reduced basal levels of FLIP protein are observed, and as such, caspase-mediated RIP degradation occurs, as does subsequent inhibition of antiapoptotic NF-κB activity. FLIP is an NF-κB-stimulated protein (34), and as such we can see in MOLT-4 and HL-60 cells that TNF induces FLIP expression (Fig. 5f), but not in death phenotype TF-1 or K562 cells, which have inhibited NF-κB activity. This is the only protein that we have found to be differentially basally expressed when life and death phenotype cells are compared. Moreover, it may be that the resting basal levels of FLIP are what define the subsequent signaling and cellular response of the cell when it encounters TNF.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meenu Wadhwa, Heather Wallace, David Kluth, Wim Buurman, and Jim Woodget for reagents, cells, antibodies, and constructs to make this work possible and colleagues in Aberdeen for comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Association for International Cancer Research.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor α; TNFR, TNF receptor; TRAF, TNFR-associating factor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; FLIP, FLICE-inhibitory protein; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt.

References

- 1.Locksley, R. M., Killeen, N. & Lenardo, M. J. (2001) Cell 104, 487–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacEwan, D. J. (2002) Cell. Signalling 14, 477–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanger, B. Z., Leder, P., Lee, T. H., Kim, E. & Seed, B. (1995) Cell 81, 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu, Z. G., Hsu, H. L., Goeddel, D. V. & Karin, M. (1996) Cell 87, 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelliher, M. A., Grimm, S., Ishida, Y., Kuo, F., Stanger, B. Z. & Leder, P. (1998) Immunity 8, 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimentel-Muinos, F. X. & Seed, B. (1999) Immunity 11, 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, S. Q., Kovalenko, A., Cantarella, G. & Wallach, D. (2000) Immunity 12, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobiume, K., Matsuzawa, A., Takahashi, T., Nishitoh, H., Morita, K., Takeda, K., Minowa, O., Miyazono, K., Noda, T. & Ichijo, H. (2001) EMBO Rep. 2, 222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuasa, T., Ohno, S., Kehrl, J. H. & Kyriakis, J. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22681–22692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi, C. S. & Kehrl, J. H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32102–32107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irmler, M., Thome, M., Hahne, M., Schneider, P., Hofmann, B., Steiner, V., Bodmer, J. L., Schroter, M., Burns, K., Mattmann, C., et al. (1997) Nature 388, 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataoka, T., Budd, R. C., Holler, N., Thome, M., Martinon, F., Irmler, M., Burns, K., Hahne, M., Kennedy, N., Kovacsovics, M., et al. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura, T., Takaku, F. & Miyajima, A. (1991) Int. Immunol. 3, 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jupp, O. J., McFarlane, S. M., Anderson, H. M., Littlejohn, A. F., Mohamed, A. A. A., MacKay, R. H., Vandenabeele, P. & MacEwan, D. J. (2001) Biochem. J. 359, 525–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed, A. A. A., Jupp, O. J., Anderson, H. M., Littlejohn, A. F., Vandenabeele, P. & MacEwan, D. J. (2002) Biochem. J. 366, 144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littlejohn, A. F., Tucker, S. J., Mohamed, A. A. A., McKay, S., Helms, M. J., Vandenabeele, P. & MacEwan, D. J. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 65, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter, G. T., Kuo, R. C., Jupp, O. J., Vandenabeele, P. & MacEwan, D. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9539–9547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul, A., Wilson, S., Belham, C. M., Robinson, C. J. M., Scott, P. H., Gould, G. W. & Plevin, R. (1997) Cell. Signalling 9, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baud, V. & Karin, M. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng, Y. B., Ren, X. Y., Yang, L., Lin, Y. H. & Wu, X. W. (2003) Cell 115, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tibbles, L. A. & Woodgett, J. R. (1999) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55, 1230–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson, H. L., Marshall, C. J. & Saklatvala, J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9486–9492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, C. Y., Mayo, M. W., Korneluk, R. G., Goeddel, D. V. & Baldwin, A. S. (1998) Science 281, 1680–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang, G. L., Minemoto, Y., Dibling, B., Purcell, N. H., Li, Z. W., Karin, M. & Lin, A. (2001) Nature 414, 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, Y., Devin, A., Rodriguez, Y. & Liu, Z. G. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2514–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karin, M. & Ben-Neriah, Y. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fotin-Mleczek, M., Henkler, F., Samel, D., Reichwein, M., Hausser, A., Parmryd, I., Scheurich, P., Schmid, J. A. & Wajant, H. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 2757–2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, X. M., Yang, Y. L. & Ashwell, J. D. (2002) Nature 416, 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Micheau, O. & Tschopp, J. (2003) Cell 114, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopp, E. & Ghosh, S. (1994) Science 265, 956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grilli, M., Pizzi, M., Memo, M. & Spano, P. (1996) Science 274, 1383–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis, J., Devin, A., Miller, A., Lin, Y., Rodriguez, Y., Neckers, L. & Liu, Z. G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10519–10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreuz, S., Siegmund, D., Scheurich, P. & Wajant, H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3964–3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micheau, O., Lens, S., Gaide, O., Alevizopoulos, K. & Tschopp, J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5299–5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]