Abstract

Background

Increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility have led to a shift in the workforce age structure towards older age groups. Deteriorating health and reduced work capacity are among the challenges to retaining older workers in the labour force.

Aims

To examine whether workplace interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity affect disability rates among employees aged 50 years and older.

Methods

Data from a survey of Norwegian companies (n = 713) were linked with registry data on their employees aged 50-61 years (n = 30771). By means of a difference-in-differences approach, we compared change in likelihood of receiving a full disability pension among employees in companies with and without workplace interventions.

Results

Employees in companies reporting to have workplace interventions in 2005 had a higher risk of receiving full disability pension during the period 2001-03 compared with employees in companies without such interventions [odds ratio (OR) 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07-1.45]. During the period 2005-07, there was an overall reduction in disability rates (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.71-0.96) in both the intervention and control group. However, employees in companies reporting to have interventions in 2005 experienced an additional reduction in an employee’s likelihood of receiving a full disability pension (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64-0.99) compared with employees in companies without interventions.

Conclusions

Interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity have reduced disability rates among employees aged 50-61. This suggests that companies’ preventive interventions are an effective means to retain older workers with deteriorating health.

Key words: Disability pension, natural experiment, older workers, workplace interventions.

Introduction

In recent decades, most countries have experienced a substantial increase in life expectancy and a decrease in fertility [1]. This has led to a shift in the population age structure towards older age groups, with a resultant ageing workforce. However, changes in workforce and population composition have not been accompanied by a sufficient increase in the effective retirement age. This has led to concerns regarding the sustainability of retirement income systems and the ability to maintain economic growth. The obvious solution to these challenges is retaining older employees in the workforce. However, health, labour market regulations, ageism, seniority wages, among other factors, may increase retirement rates [2].

In Norway, disability pension is granted following a permanent reduction in earnings capacity due to either illness or injury, or both. As Norway has one of the highest disability rates in Europe [3], efforts to reduce sick leave and disability have been prioritized in the last decade. By means of the agreement on an inclusive working life (IW-agreement), the Norwegian government and the social partners (main employee and employer organizations) are committed to retaining more employees with health problems and reduced work ability [4]. Different measures have been implemented by government, such as earlier and continuous attention to workers on sick leave, increased use of graded sick leave (a combination of reduced work tasks/hours and sickness benefit) and access to work adjustment subsidies and wage subsidies. In addition, employer and employee organizations have been campaigning to get more companies to use interventions to prevent health problems such as chronic injuries and illnesses among older workers and to facilitate work for employees with poor health and reduced work ability.

Both individual and work characteristics can influence the likelihood of becoming disabled. Previous research has shown that disability rates vary by gender, age, education, income, marital status, work hours and sickness absence [5-8], and by industry [9,10], presence of human resource (HR) management, competitiveness, downsizing experience [11-13] and if and when the company joined the IW-agreement. In addition, combined indices on the work ability of employees and workplaces are correlated with retirement behaviour and disability [14,15].

In addition, almost 60% of self-reported health problems are associated with work conditions [16]. Within company interventions are therefore considered to be an important mean to reduce disability rates [17]. Earlier Norwegian studies found no effect of working in an IW company [18,19]. However, the dependent variable in these studies was sickness absence, not disability. In addition, one of the studies [18] only looked at the effect of working in a company with or without an IW-agreement and not the effect of working in a company with or without preventive workplace interventions. In other words, they have mainly measured the possible effect of working in a company that has access to different public services offered exclusively to IW companies and not the effect of actually having access to preventive workplace interventions. The aim of this study therefore was to investigate whether access to workplace interventions, initiated and financed by the employer, influences the individual probability of retiring on a disability pension among older workers, and whether such interventions are an effective means to retain older works with deteriorating health [20].

Methods

In 2005, Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research, in collaboration with Statistics Norway, conducted a survey to map the prevalence of different IW-related interventions among a representative sample of Norwegian companies with >10 employees, of which at least one employee was aged 60 or older (n = 713). The sample was stratified according to industry and company size [21,22]. The survey, with a response rate of 73%, included questions on workplace interventions employed to facilitate work for employees with poor health and/or reduced work ability, as well as other company characteristics.

In this study, the company survey data, by means of the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administrations’ State Register of Employers and Employees, were linked to employee registry data from SSB on individual characteristics, work and sickness absence in 2001 and 2005 and disability in 2001-03 and 2005-07 for all employees aged between 50 and 61 in 2001 and 2005, respectively. The data allowed identification of employees working in companies with and without workplace interventions. Consequently, this natural experimental design [23] allowed investigation of whether workplace interventions had a causal effect on disability rates and enabled an intention-to-treat analysis, using a difference-in-differences approach [24]. The project was approved by The Data Protection Official and Norwegian data protection authorities.

Our dependent variable measured whether an individual became 100% disabled (i.e. received a full disability pension from the national insurance system) during the follow-up period. Individuals who were <100% disabled, and who were still working part time, were treated as employed.

Our principal independent variable was whether companies had initiated interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity in 2005.

The most commonly reported workplace interventions included a variety of work adjustments, e.g. use of technical aids, change of role or work tasks, reduced working hours and, less commonly, sabbaticals, physio therapy and physical exercise. In our analysis, we measured the total effect of working in a company offering some sort of workplace intervention.

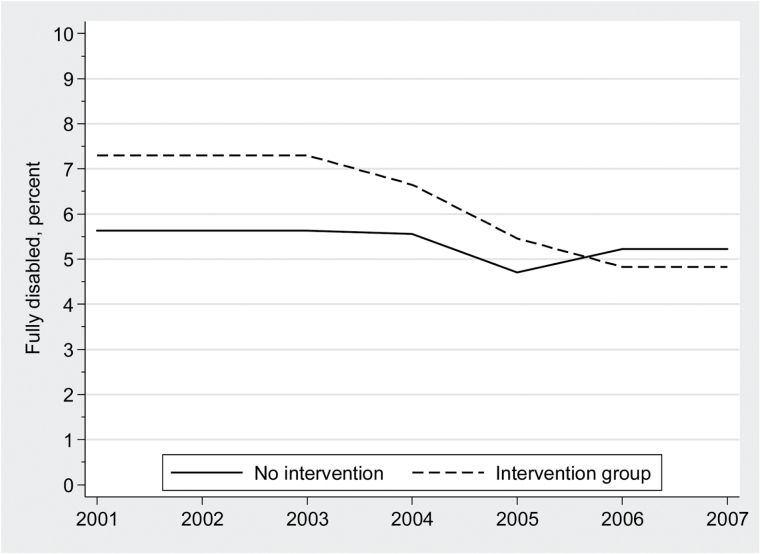

Using a difference-in-differences approach presumes that the samples are drawn randomly, giving equal likelihood of inclusion in the intervention group and the control group [24]. The group of Norwegian companies that offered workplace interventions were self-selected. However, we found that employees in companies offering interventions were similar to employees in companies without interventions when it came to educational level, average age, proportion of female employees, proportion of part-time employees, income level and sickness absence rates (see Table 1). We therefore assumed that our sample was random. Another assumption in the difference-in-differences approach is that the trends are the same in the treatment and control group in the absence of treatment [24]. Thus, disability trends in our data should be similar until the interventions were introduced and should, given that the intervention has an effect, differ after the interventions were in place. This pattern was found in our data (see Figure 1 below).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| 2001 | 2005 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Interventionsa, n (%) | No interventions, n (%) | Interventionsa, n (%) | No interventions, n (%) |

| Female | 2252 (40) | 3404 (42) | 2863 (40) | 3940 (40) |

| Mean age (SD) | 55.9 (4.4) | 56.1 (4.5) | 56.2 (4.4) | 56.2 (4.5) |

| Education level | ||||

| Primary education | 1174 (21) | 1370 (17) | 1272 (18) | 1518 (15) |

| Upper secondary school | 2869 (51) | 4102 (51) | 3772 (52) | 5023 (51) |

| College/university, bachelor’s level | 1182 (21) | 1754 (22) | 1589 (22) | 2258 (23) |

| College/university, master’s level | 408 (7) | 812 (10) | 597 (8) | 1071 (11) |

| Living alone | 853 (15) | 1317 (16) | 1136 (16) | 1572 (16) |

| Mean number of sick days (SD) | 16.7 (32.6) | 14.2 (30.0) | 12.4 (26.4) | 11.5 (25.2) |

| Mean income percentile (SD) | 50.4 (27.8) | 50.6 (29.6) | 49.4 (28.3) | 51.3 (29.2) |

| Part time, short (<20 h) | 430 (8) | 779 (10) | 504 (7) | 789 (8) |

| Part time, long (20-30 h) | 464 (8) | 893 (11) | 768 (11) | 752 (8) |

| Full-time employment | 4739 (84) | 6366 (79) | 5958 (82) | 8239 (84) |

| Employed in establishments | ||||

| With >230 employees | 1647 (29) | 2154 (27) | 2431 (34) | 3088 (31) |

| With HR departmentb | 3683 (65) | 6128 (76) | 5186 (72) | 7685 (78) |

| In competitive sector | 2593 (46) | 4133 (51) | 3250 (45) | 4957 (50) |

| In private sector | 3509 (62) | 4615 (57) | 4289 (59) | 5801 (59) |

| Which has downsized last 5 years | 3145 (56) | 4261 (53) | 3968 (55) | 5424 (55) |

| Industry | ||||

| Manufacturing | 451 (8) | 1010 (13) | 465 (6) | 1114 (11) |

| Construction | 597 (11) | 900 (11) | 808 (11) | 1034 (10) |

| Retail | 447 (8) | 875 (11) | 528 (7) | 1152 (12) |

| Hotels and restaurants | 725 (13) | 539 (7) | 776 (11) | 603 (6) |

| Public administration | 644 (11) | 1106 (14) | 1101 (15) | 1251 (13) |

| Teaching | 1057 (19) | 1096 (14) | 1180 (16) | 1240 (13) |

| Health and social services | 381 (7) | 1239 (15) | 574 (8) | 1474 (15) |

| Other industries | 1331 (24) | 1273 (16) | 1798 (25) | 2002 (20) |

| IW-establishment starting 2001c | 575 (10) | 1142 (14) | 870 (12) | 921 (9) |

| IW-establishment 2002-05c | 3964 (70) | 4870 (61) | 5022 (69) | 6535 (66) |

| n | 5633 | 8038 | 7230 | 9870 |

Employees aged 50-61 years in 2001 and 2005 by companies with or without interventions (introduced in 2005) to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity.

aInterventions were introduced in 2005.

bEstablishments with HR department.

cEstablishments which participated in the Inclusive Working Life Agreement.

Figure 1.

Annual disability rates among employees aged 50-61 years in establishments with and without interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity (per cent, 2001-07).

In our analysis, we compared the individual probability of receiving a disability pension during the period 2001-03 with the probability of receiving a disability pension during the period 2005-07 among individuals aged between 50 and 61 in companies with and without workplace interventions. To reduce the extent of ‘healthy worker’ selection, we compared two overlapping groups which each comprised a cross-section of workers: i.e. those aged 50-61 years in 2001 and those aged 50-61 years in 2005.

We included controls for the following individual characteristics: gender and age including a second-order polynomial to allow for non-linearity, education and income level. In addition, we adjusted for number of days absent due to sickness including a second-order polynomial to allow for non-linearity.

All information pertaining to the different establishments originated in the survey conducted in November and December 2005. All establishment variables were categorical. We adjusted for industry, establishment size, whether the establishments had an HR department or a specific person that was responsible for the HR policy of the establishment, whether they were exposed to competition and whether they had experienced downsizing through 2001-05.

In addition, adjusting for participation in the IW-agreement was important since such establishments have access to public services and benefits which are not available to other establishments.

The dependent variable in our analyses was a binary categorical variable, thus we used logistic regression. We reported odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). As an additional control, we also estimated linear probability models, which substantiated our reported estimates. Stata, version 13.1, was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

The overall annual trend in disability rates before and after 2005 is shown in Figure 1. Although the disability rates in 2001 were higher in companies with interventions than in companies without, the yearly change in disability rates for both groups of companies was almost the same up to 2005. However, in 2004/2005, there was a marked change in trends, where the disability rates for companies offering preventive interventions declined, while the disability rates for companies without such interventions did not.

We first looked at the effect of workplace interventions by only including the interventions and a period dummy, as well as the intervention effect (i.e. an interaction between workplace interventions and period). This gave a gross effect of the interventions. Thereafter, we controlled for individual characteristics, and then for company characteristics.

Interventions targeting individuals aged 50-61 with health problems and reduced work ability reduced individual disability risk (see Table 2). During the period 2001-03, employees in companies reporting to have workplace interventions in 2005, had a higher risk of full disability compared with employees in companies without such interventions (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.07-1.45). During the period 2005-07, there was an overall reduction in disability rates (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.71-0.96) in both the intervention and control group. However, employees in companies reporting to have interventions in 2005 experienced an additional reduction in employee likelihood of receiving a full disability pension (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64-0.99) compared with that in companies without interventions in 2005.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted ORs for disability pension by health intervention and time

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI (95%) | P | OR | 95% CI (95%) | P | |

| Female | 0.86 | 0.75-0.99 | <0.05 | |||

| Age | 1.51 | 1.44-1.59 | <0.001 | |||

| Age squared | 0.98 | 0.98-0.98 | <0.001 | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary education (ref.) | 1.00 | |||||

| Secondary education | 0.88 | 0.77-1.01 | NS | |||

| Short university/college | 0.78 | 0.64-0.96 | <0.05 | |||

| Long university/college | 0.54 | 0.39-0.75 | <0.001 | |||

| Living alone | 1.30 | 1.13-1.49 | <0.001 | |||

| Number of sick days | 1.04 | 1.03-1.04 | <0.001 | |||

| Number of sick days squared | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | <0.001 | |||

| Income level | 0.99 | 0.99-0.99 | <0.001 | |||

| Full-time employment (ref.) | 1.00 | <0.001 | ||||

| Part time, short (<20 h) | 2.41 | 2.02-2.88 | <0.001 | |||

| Part time, long (20-30 h) | 0.97 | 0.80-1.17 | NS | |||

| Employed in establishments | ||||||

| >230 employees | 0.92 | 0.81-1.05 | NS | |||

| HR personnela | 1.08 | 0.95-1.23 | NS | |||

| Competitive sector | 1.23 | 1.01-1.49 | <0.05 | |||

| Private sector | 1.22 | 0.89-1.66 | NS | |||

| Downsized last 5 years | 1.17 | 1.04-1.32 | <0.01 | |||

| Industry | ||||||

| Hotels and restaurants (ref.) | 1.00 | |||||

| Manufacturing | 0.83 | 0.64-1.08 | NS | |||

| Construction | 1.35 | 1.06-1.71 | <0.05 | |||

| Retail | 0.71 | 0.55-0.92 | <0.05 | |||

| Public administration | 1.18 | 0.82-1.71 | NS | |||

| Teaching | 1.71 | 1.20-2.44 | <0.01 | |||

| Health and social services | 1.27 | 0.92-1.77 | NS | |||

| Other industries | 0.96 | 0.77-1.19 | NS | |||

| Non IW-establishmentb (ref.) | 1.00 | |||||

| IW-establishment starting 2001 | 0.81 | 0.65-1.02 | NS | |||

| IW-establishment 2002-05 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.07 | NS | |||

| Intervention group | 1.33 | 1.16-1.53 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 1.07-1.45 | <0.01 |

| Period: 2005-07 versus 2001-03 | 0.74 | 0.64-0.84 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.71-0.96 | <0.05 |

| Intervention effect (intervention * period) | 0.80 | 0.66-0.99 | <0.05 | 0.80 | 0.64-0.99 | <0.05 |

| Pseudo R 2 | 0.006 | 0.194 | ||||

| n | 30771 | 30771 | ||||

Adjusted by individual and establishment characteristics. NS, not significant.

aEstablishments with HR personnel.

bEstablishments which participated in the Inclusive Working Life Agreement.

Corroborating previous research, in our adjusted model, we found that disability risk was higher among women, the less educated, those living alone, part-time workers and older workers. In addition, prior sick leave increased disability risk. The disability risk also varied by industry. Employees in retail and teaching had higher disability rates than employees in other industries.

Discussion

This study found that company interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity did reduce disability risk among employees aged 50-61. The impact of the interventions was significant after adjusting for relevant individual and company characteristics. The results thus indicate that work adjustments targeting employees with health problems or reduced work capacity may have contributed to preventing permanent exclusion from employment among older workers. This finding may in part explain the overall reduction in disability rates among individuals aged over 55 in Norway over the last decade, following the introduction of the IW-agreement and the subsequent increase in companies’ use of preventive measures [25].

Strengths of our study include the use of linked employer–employee data, which enabled us to identify which employers introduced interventions and to assess how interventions influenced disability as recorded in national registers. In addition, we were able to adjust our analysis by individual characteristics from a variety of administrative registers with full coverage and good accuracy.

However, we had no access to data that allowed us to control for differences related to working environments and working conditions. These are factors, which, as demonstrated by previous studies, influence disability [26]. Future studies should aim at including such variables.

As discussed above, disability risk is also influenced by characteristics such as age, gender, educational level and income, which is due to disability risk variation between occupations, different work environments, as well as health status and workload. The relation between living alone and increased disability risk is consistent with previous findings [27]. Poor health is a prerequisite for the disability pension, thus it is not surprising that prolonged sick leave increased disability risk. However, that reduced work hours increased disability rates is perhaps surprising. One explanation for this might be that working hours were contractual, and not actual. Thus, some might work more than specified in their employment contract. Individuals with a part-time contract wanting to work more hours could also experience more stress and inconvenience due to unpredictable working hours. The latter is common in Norwegian health and social services. Part-time workers may also experience more ill health, and thus part-time work could be a consequence of (acquired) reduced work capacity.

Employees in companies exposed to competition were more likely to become disabled. This may be caused by higher work demands and lower tolerance for reduced individual productivity. Furthermore, recent downsizing increased disability rates, which is consistent with previous findings [11-13].

This study investigated whether working in a company offering preventive workplace measures targeting workers with poor health and/or reduced work ability reduced the individual probability of being declared 100% disabled. Future surveys may target the employees, rather than the company, to investigate whether eligible employees have actually been included in interventions aiming to prevent sickness absence and disability. In addition, future analyses may also investigate whether different interventions have different effects on disability risk in different industries and occupations.

This study investigated whether disability rates among employees aged 50-61 was reduced more in companies with interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity than in companies without such interventions. It found that interventions to facilitate work among employees with health problems or reduced work capacity reduced disability rates among employees aged 50-61 years. This suggests that companies’ preventive measures delayed work exits among older workers. Thus, policymakers may want to consider means to facilitate the introduction of such interventions among companies where they are not present today. Our findings suggest that the use of such interventions may be a key to reducing disability rates among 50- to 61-year olds.

Key points

Workplace interventions to facilitate work among employees aged 50-61 with health problems or reduced work capacity reduced disability rates, thus such interventions are an efficient means to retain older workers.

The significance of interventions was not altered by adjusting for individual and company characteristics associated with increased disability risk.

Future studies on interventions to facilitate work should investigate whether all eligible individuals are included in relevant interventions and whether different types of interventions have different effects on disability rates.

Funding

The project was funded by FARVE – Forsøksmidler arbeid og velferd (The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions.

References

- 1. United Nations. World Population Ageing: 1950-2050. New York: UN, DESA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2011: Retirement-Income Systems in OECD and G20 Countries. Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eurostat. Active Ageing and Solidarity Between Generations. A Statistical Portrait of the European Union 2012. Luxembourg: EU, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. IW-Agreement. Protocol Between the Employer/Employee Organisations and the Authorities for a Joint Effort to Prevent and Reduce Sick Leave and Promote Inclusion. Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2010. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/labour/the-working-environment-and-safety/inclusive-working-life/ia-tidligere-avtaleperioder/inkluderende-arbeidsliv.-avtaleperioden-2010-2013/ia-dokumenter/New-IA-agreement-and-stimulus-package-to-reduce-sick-leave-/id594043/ (18 November 2016, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siegrist J, Wahrendorf M, von dem Knesebeck O, Jürges H, Börsch-Supan A. Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees: baseline results from the SHARE Study. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:62-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bound J, Schoenbaum M, Stinebrickner TR, Waidmann T. The dynamic effect of health on the labor force transitions of older workers. Labour Econ 1999;6:179-202. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruusgaard D, Smeby L, Claussen B. Education and disability pension: a stronger association than previously found. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:686-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, Alexanderson KA. Risk factors for disability pension in a population-based cohort of men and women on long-term sick leave in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chirikos TN, Nestel G. Occupational differences in the ability of men to delay retirement. J Human Resour 1991;26:1-26. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krause N, Lynch J, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Goldberg DE, Salonen JT. Predictors of disability retirement. Scand J Work Environ Health 1997;23:403-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrie JE. Is job insecurity harmful to health? J R Soc Med 2001;94:71-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Røed K, Fevang E. Organisational change, absenteeism and welfare dependency. J Human Resour 2007;42:156-193. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sverke M, Hellgren J, Näswall K. No security: a meta-ana lysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J Occup Health Psychol 2002;7:242-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tuomi K, Huuhtanen P, Nykyri E, Ilmarinen J. Promotion of work ability, the quality of work and retirement. Occup Med (Lond) 2001;51:318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alavinia SM, de Boer AG, van Duivenbooden JC, Frings-Dresen MH, Burdorf A. Determinants of work ability and its predictive value for disability. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehlum IS, Kjuus H, Veiersted KB, Wergeland E. Self-reported work-related health problems from the Oslo Health Study. Occup Med (Lond) 2006;56:371-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Härmä M. Adding more years to the work careers of an aging workforce—what works? Scand J Work Environ Health 2011;37:451-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foss L, Gravseth HM, Kristensen P, Claussen B, Mehlum IS, Skyberg K. ‘Inclusive working life in Norway’: a registry-based five-year follow-up study. J Occup Med Toxicol 2013;8:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Midtsundstad TI, Nielsen RA. Do work-place initiated measures reduce sickness absence? Preventive measures and sickness absence among older workers in Norway. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cloostermans L, Bekkers MB, Uiters E, Proper KI. The effectiveness of interventions for ageing workers on (early) retirement, work ability and productivity: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:521-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gravem DF, Villund O. Undersøkelse om seniorpolitikk i norske virksomheter, fase 1. Dokumentasjonsrapport. Oslo, Norway: Statistics Norway, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Midtsundstad T. Fra utstøting til inkludering. En kartlegging av norske virksomheters arbeidskraftstrategier overfor eldre arbeidstakere. Fafo-rapport. Oslo, Norway: Fafo, 2007:37. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D, et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1182-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Angrist JD, Pischke J-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bragstad T, Ellingsen J, Lindbøl MN. Hvorfor blir det flere uførepensjonister? Arbeid og velferd 2012;6:26-39. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave—general studies. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(Suppl. 63):36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramm J, Jensen A, Borgan J-K. Helse og levevaner, uførhet og dødelighet. In: Mørk E, ed. Aleneboendes levekår. Statistiske Analyser. 81. Oslo, Norway: Statistics Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]