Abstract

Objective: To investigate whether differentiation or cellular confluence is responsible for CXCL11 expression patterns in re-epithelialization.

Approach: In vitro model systems of re-epithelialization using the HaCaT keratinocyte cell line were utilized in monitoring expression of differentiation markers, including desmoplakin and various cytokeratins while evaluating for an association with chemokine CXCL11 expression.

Results: CXCL11 expression was elevated in sparse culture with peak expression near the time of confluence. This somewhat followed the accumulation of desmoplakin in detergent-insoluble pool of proteins. However, in postconfluent, despite continued accumulation of desmoplakin within cells, CXCL11 expression decreased to baseline levels. This biphasic pattern was also seen in low calcium culture, an environment that inhibits keratinocyte differentiation and accumulation of desmosomal proteins. Highest CXCL11-expressing areas best correlated with newly confluent areas within culture expressing basal keratin 14, but also activated keratin 6.

Innovation: Achievement of a threshold cellular density induces cell signaling cascade through CXCR3 that, in addition to other undiscovered pathways, can progress cutaneous wounds from the proliferative into the remodeling phases of cutaneous wound healing.

Conclusion: These results suggest that the achievement of confluence with increased cellular density by migrating keratinocytes at the wound edge triggers expression of CXCL11. Since CXCR3 stimulation in endothelial cells results in apoptosis and causes neovascular pruning, whereas stimulation of CXCR3 in fibroblasts results decreased motility and cellular contraction, we speculate that CXCL11 expression by epidermal cells upon achieving cellular confluence could be the source of CXCR3 stimulation in the dermis ushering a transition from proliferative to remodeling phases of wound healing.

Keywords: : wound healing, hemokine signaling, contact inhibition, CXCR3, CXCL11, keratinocyte

Arthur C. Huen, MD, PhD

Introduction

A lesser-explored aspect of wound healing is the coordinated cessation of cellular hyperproliferation that occurs as the tissue regenerative phase comes to an end. In cutaneous wound healing, the hyperproliferative granulation tissue has a hypercellular and hypervascular appearance similar to that of a neoplasm, however, wounds typically revert dramatically into quiescent scar tissue.1 Ideally, this transition occurs around the time when either the granulation tissue completes filling the space defect of the wound or re-epithelialization of the wound by keratinocytes is completed. A regulator or cascade of signals to regulate this transition would need to coordinate not only the overlying keratinocytes, but also the underlying fibroblasts, and endothelial cells.2

Signaling through the CXCR3 pathway is present and active in the various cellular compartments during cutaneous wound healing and represents a key regulator in the transition between the proliferative and remodeling phases.3–6 Conditional knockout of CXCR3 in mouse cutaneous wound healing models show a significant delay in wound maturation and a persistence of hypercellularity and vascularity.4 In addition, signaling through CXCR3 may provide the crosstalk or coordination between the dermis and epidermis to synchronize wound resolution of both of those compartments. Of the CXCR3 ligands, which include CXCL9 (MiG), CXCL10 (IP-10), and CXCL11 (IP-9, I-TAC), CXCL11 appears to play a strong role in this transition. Silencing of this chemokine in the epidermis results in a significantly delayed maturation of the wound in the upper dermis similar to loss of the CXCR3 receptor.4 In addition, stimulation of CXCR3 by CXCL11 in fibroblasts decreases fibroblast migratory ability7,8 and increases transcellular tension9; these two properties are critical to matrix contraction and strengthening. In endothelial cells, stimulation of CXCR3 results in cessation of angiogenesis, but also causes involution of newly formed blood vessels. In the CXCR3 null mouse, nascent vessels in cutaneous wounds appear to persist longer compared to normal control mice. Similarly, in vitro formed endothelial cell cords and immature vessels in vivo were dissociated by stimulation of CXCR3.10,11

However, the molecular mechanisms controlling the timing of CXCL11 expression during cutaneous wound healing remains unknown. CXCL11 expression patterns by keratinocytes in human tissue and mouse models of wound healing have previously been described.4,7,10 In those studies, increased CXCL11 expression is observed in a region between the compacted cells remote from the wound edge and the flattened, migrating keratinocytes invading into the wound bed. Most notably, the cells expressing the highest levels appear to be basally located. This peculiar expression pattern suggests a complex mechanism by which secretion of this chemokine is initiated and then downregulated in a transient fashion.

Results within this study suggest that re-establishment of a threshold cellular density within the wound bed by migrating keratinocytes initiates CXCL11 expression. This signal is capable of promoting keratinocyte migration to further promote re-epithelialization. We further speculate that the location and timing of CXCL11 expression by keratinocytes that have successfully re-epithelialized the wound bed may play a role in the transition between proliferative and remodeling phases of wound healing since CXCR3 stimulation has inhibitory effects on fibroblasts and endothelial cells.4–7,10,11

Control mechanisms that regulate remodeling phase of cutaneous wounds are still largely undiscovered. Derangements of this phase of wound healing can result in hypertrophic and keloid scars that are unsightly and painful, or in atrophic or contracted scars that can lead to disability. Understanding molecular mechanisms that transform the proliferative phase, a milieu characterized by many highly migratory and proliferative cells into scar, which is quiescent and typically hypocellular, will aid in the treatment of chronic cutaneous wounds, burn scars, and the ice pick and boxcar scars of acne. However, these pathways may also provide insight into carcinogenesis, which features the escape of cells from a quiescent differentiated tissue into a proliferative mass and possibly develop a highly migratory phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies

Anti-ITAC rabbit polyclonal antibody (500-P132; PeproTech), DP2.15 mouse monoclonal antibody (03-65003), anti-cytokeratin 6, anti-cytokeratin 10, and anti-cytokeratin 14 (American Research Products, Inc.), anti-desmoplakin rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab71690) and anti-CXCL11 rabbit polyclonal (Abcam), anti-GAPDH rabbit polyclonal (G9545) from Sigma, anti-alpha catenin sc-7894 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and anti-E-cadherin (24E10; Cell Signaling Technology). Amido Black was used for protein quantification (N3393; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). The Click-IT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit was used to stain proliferative cells (Thermo Fisher).

Tissue culture

HaCaT cells were a kind gift from Dr. N. Fusenig at the DFG (Heidelberg, Germany). For scratch wound, HaCaT cell cultures growing on glass coverslips were wounded with a P1000 micropipette tip or with a Beaver-style miniature, chisel-type, surgical blade (374562; BD Beaver), after at least 4 days of growth at confluence. Cultures were cultured an additional 1–2 days before coverslips were harvested for immunofluorescence analysis. A431 cell line was from ATCC.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded onto flame-sterilized glass coverslips. For colony outgrowth, Nunc® Lab-Tek® II Chamber Slide™ system with a 4 mm diameter chamber was used. After cellular confluence was reached, the silicon mask was removed and the colony was allowed to outgrow. Cultures were rinsed thrice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 min. Blocking of nonspecific antibody binding was achieved with 30 min incubation in bovine serum albumin 100 mg/mL in PBS. Primary antibody dilution was then added to the glass slides overnight. After rinsing, fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and 594, 1 ng/mL) were applied for 1 h and subsequently rinsed three times in PBS. This was followed by incubation with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 100 ng/mL.

Sequential detergent extraction

HaCaT cell cultures were seeded at varying cellular confluencies in triplicate by adding 5 × 105 cells to 35, 60, or 100 mm tissue culture dishes. Cell densities and calculated total cell numbers were determined by counting cells manually from photomicrographs taken with an inverted phase microscope. Three separate areas per culture plate were analyzed before cell harvesting for detergent extraction 48 and 96 h after seeding. Calculated total cell counts were used to control for gel loading as GAPDH and β-actin are not linear at high cellular densities. After PBS washes, cells were then incubated on ice with 400 μL of saponin buffer for 5 min (saponin buffer: 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 0.01% saponin, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, protease inhibitor mix; Amersham). Cells were harvested with a cell scraper and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 g. Supernatant (saponin-soluble pool) was collected. The pellet was vortexed with Triton X-100 buffer for 30 s (Triton X-100 buffer: 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor mix; Amersham). Supernatant (Triton X-100-soluble pool) was collected after centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in 40 μL sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer, and was heated for 10 min in boiling water bath. This SDS pool was diluted using dilution buffer (SDS buffer: 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor mix [Amersham]; dilution buffer: 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor mix; [Amersham]). Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis.

Immunoblotting

3× Laemmli buffer (30% glycerol, 3% SDS, 0.1875 M Tris, 3% beta-mercaptoethanol, and 1× protease inhibitor mix; Amersham) was added to cell lysates and sequential detergent extraction fractions followed by boiling for 10 min. Homogenization was achieved with ultrasonication. SDS-PAGE was performed using 7.5% gel for desmoplakin, E-cadherin, and α-catenin and 15% gel for CXCL11. Protein transfer to PVDF membrane was performed overnight at 20 volts. For dot blotting, cell-free tissue culture supernatant was applied to nitrocellulose membrane using the MultiScreenHTS Vacuum Manifold (EMD Millipore). Western blot bands and dot blot signal were analyzed using ImageJ image analysis software.34

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

The mRNA was harvested HaCaT cell cultures were harvested using the RNeasy Mini Kit (74104; Qiagen). Reverse transcription and first-strand synthesis were accomplished using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (205310; Qiagen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on a Stratagene Mx3000P Real-time PCR System. Primer pairs were described previously39 and are as follows: CXCL11 forward 5′-ATGAGTGTGAAGGGCATGGC-3′, CXCL11 reverse 5′-TCACTGCTTTTACCCCAGGG-3′; GAPDH forward 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′, GAPDH reverse 5′-TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG-3′.

Results

Expression of CXCL11 is upregulated just behind the migrating edge, but not in quiescent confluent culture regions

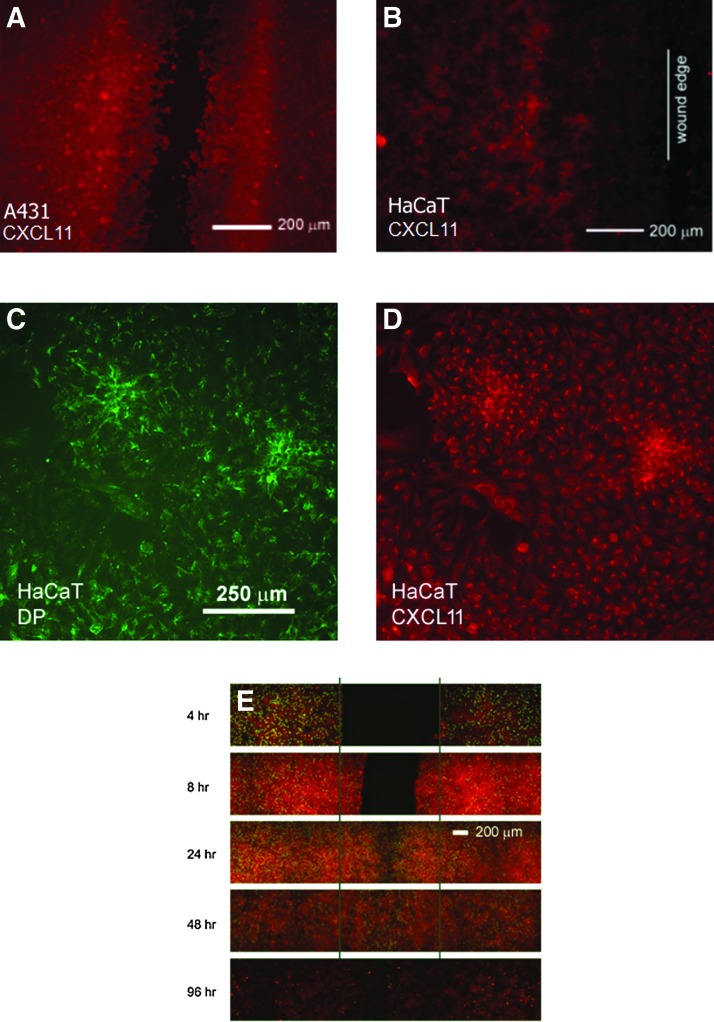

Scratch-wounded A431 cell monolayers (Fig. 1A) showed a distinctive expression pattern for CXCL11 near scratch wounds. Cells were plated onto glass coverslips at confluent cell density, allowed to settle, and adhere. The confluent monolayer was then scratch-wounded using a 1,000 μL pipette tip or Beaver-style surgical blade. Monolayers were allowed 24–96 h to heal. A distinct pattern of expression was observed that was similar to that seen in vivo4 with increased CXCL11 expression trailing the leading edge of the wound. The spontaneously immortalized HaCaT keratinocyte cell line (Fig. 1B) was also used in this in vitro wound assay to model keratinocyte re-epithelialization, since this cell line is not considered malignant and display contact inhibition, unlike A431 cells. Immunofluorescent staining of scratch-wounded monolayers (Fig. 1A, B) revealed CXCL11 expression to be elevated in a region near the scratch wound behind the leading edge. Cells in this area tend to be more densely packed compared to the more flattened cells at the wound edge. Initially proliferative activity is increased in regions further away from the wound edge. Once the cells have filled in the wound bed, they also become proliferative as seen at 24 h. Proliferative activity is confined predominantly to the previously wounded area at 48 h after wounding. Finally, by 96 h, there is very little proliferation as seen by EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) staining (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1.

CXCL11 expression in scratch-wounded monolayer culture. A431 cell monolayer (A) and HaCaT cell monolayer (B) were scratch wounded and allowed to close for 24–48 h. The vertical line in panel B is drawn on the leading edge of HaCaT cells. While there is baseline expression of CXCL11 distant from the wound edge, there is a region of elevated CXCL11 expression that follows somewhat behind the wound edge. At the wound edge, CXCL11 expression is negligible. (C, D) Colocalization of CXCL11 expression in cells with established desmosomes. Areas in monolayer culture demonstrating increased CXCL11 expression (red) also have more established networks of intercellular desmosomes (green, desmoplakin [DP] antibody staining). CXCL11 expression (red) greatest 24–48 h after scratch injury (E), whereas proliferation (Click-iT EdU, green) mostly occurs behind the wound edges.

In subconfluent culture, higher CXCL11 expression was seen in areas where cellular density was high (Fig. 1D). The regions where CXCL11 expression was increased also corresponded to regions with increased staining for desmoplakin, a desmosomal protein (Fig. 1C) and a marker of keratinocyte differentiation.

Since the cells within this region of increased CXCL11 expression are more compacted than those at the wound edge and are forming desmosomes, a key marker of keratinocyte differentiation, this region may represent cells that are transitioning from migratory phenotype into a more homeostatic phenotype, in other words, redifferentiating.12 This raised the question of whether differentiation was a trigger for CXCL11 expression.

Upregulation of CXCL11 as cells achieve confluence and downregulation at cellular compaction

To see if differentiation is a possible trigger for CXCL11 expression, HaCaT cells were monitored over time to see if the timing of CXCL11 expression matched differentiation as measured by desmoplakin expression. Monolayer cultures that were allowed to mature for at least 96 h were wounded by trypsinization. Compared to making 15–20 scratch wounds on a tissue culture dish, complete trypsinization of an entire monolayer result in disruption of all cells of a monolayer, rather than a minority of cells residing along the edges of a scratch wound. In addition, since all the cells in the culture downregulate desmosomes to aid in mobilizing to re-epithelialize the culture dish, the status of desmosome formation, specifically the detergent solubility of desmosomal proteins, could be more easily monitored. As keratinocytes establish cell–cell contact and form desmosomes, the strong intercellular adhesion provided by adherens junctions and desmosomes is associated with the transition of the junctional proteins from a detergent-soluble to a detergent-insoluble state, a state that has been named hyperadhesive.13–15,40

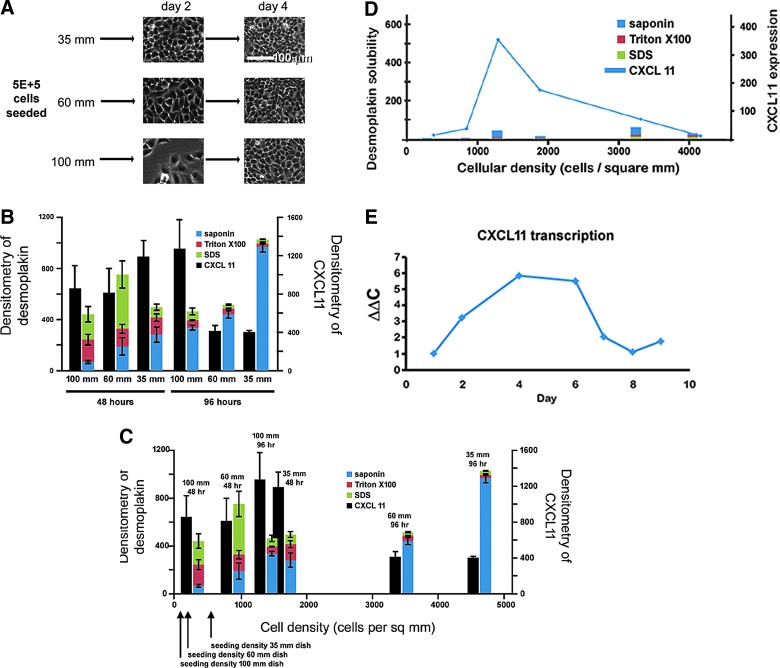

By plating 5 × 105 HaCaT cells onto 35, 60, and 100-mm tissue culture dishes, densely confluent (greater than 2,000 cells/mm2), just confluent (1,000–2,000 cells/mm2), and subconfluent (less than 1,000 cells/mm2) cultures could be established at 48 h of culture, respectively. At 96 h, the 35-mm plate remained densely confluent and compacted, and the 60-mm dish also became densely confluent and compacted, looking much like the 35-mm culture at 48 h. The 100-mm dish at 96 h was just achieving confluence similar to the 60-mm culture at 48 h (Fig. 2A). With this plating technique, conditions of the preconfluent, just confluent, and postconfluent/compacted monolayers relative to desmosomal protein expression and CXCL11 expression could be analyzed. Detergent solubility of desmosomal protein desmoplakin was analyzed at 48 and 96 h after plating (Fig. 2B). Cell fractionation using progressively stronger detergent extractions can allow analysis of cytoplasmic (saponin-soluble), membranous organelle-associated (Triton X-100-soluble), and cytoskeletal (Triton X-100-insoluble) proteins.16–18 At the 48 h time points, there are low amounts of desmoplakin protein in all three detergent pools in sparse, confluent, and compact cultures. By 96 h after plating, however, there is a dramatic increase in total cellular desmoplakin in all cultures and the majority of the protein appears to be in an SDS-soluble pool after sequential detergent extraction. As expected in normal calcium culture conditions, there is progressive accumulation of desmoplakin in the Triton X-100-insoluble pool of proteins as the desmosome network is being assembled.

Figure 2.

Sequential detergent extraction of desmoplakin. Equal numbers of HaCaT keratinocytes (5 × 105) were plated onto 35-, 60-, and 100-mm culture dishes in triplicate (A). Cells were harvested at 48 h and 96 h after plating. Images of cell cultures were taken at 10× magnification (white bar is 100 μm). Proteins were extracted using saponin (blue), Triton X-100 (red), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-containing buffers (green). As expected at 96 h, there was a dramatic shift of desmoplakin into the Triton-insoluble (SDS) pool of proteins as assessed by densitometry of western blot signal. CXCL11 expression, however, did not follow the same temporal pattern of expression (black). Error bars represent standard error the mean of measurements (B). Sequential detergent extraction data replotted as a function of cellular density shows elevated CXCL11 expression cultures at or below confluency (less than 2,000 cells/mm2) (C). Sequential detergent extraction was performed at 48 h and 96 h in HaCaT cultures in low calcium media, inhibiting desmosome formation. Note that the biphasic expression of CXCL11 expression remained, despite lack of desmoplakin accumulation (D). Semiquantitative RT-PCR of CXCL11 transcript levels of 5 × 105 HaCaT cells cultured in 100-mm culture dishes over 9 days (E). Data shown in (D, E) are representative of at least three separate experiments.

CXCL11 secretion in these cultures was also analyzed by dot blot technique of cell culture media. Interestingly, the timing of CXCL11 expression did not follow the behavior of desmoplakin expression (Fig. 2B). While desmoplakin accumulation was progressive with length of time in culture, CXCL11 secretion was biphasic. As cultures became confluent (1,000–2,000 cells/mm2), there was increased CXCL11 expression over the moderate expression seen in sparse culture (less than 1,000 cells/mm2). Once cultures became compacted (greater than 2,000 cells/mm2), however, CXCL11 expression became low. This relationship is better highlighted once the data are replotted as a function of cellular density (Fig. 2C).

This result was intriguing because CXCL11 expression does not appear to correlate with time in culture. Two cultures with similar cellular density, but having been in culture for differing amounts of time (35-mm plate at 48 h and 60-mm plate at 96 h), had very similar low levels of CXCL11 expression. Similarly, cultures that were just achieving confluency (60-mm plate at 48 h and 100-mm plate at 96 h) had the highest CXCL11 expression, despite being grown for different periods of time. Taken together, reaching a threshold cellular density rather than desmosome formation is more likely the trigger for CXCL11 expression.

Transcription of CXCL11 messenger RNA also followed a similar expression pattern (Fig. 2E). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed on HaCaT cell cultures that were seeded sparsely (5 × 105 in 100-mm culture dish) and allowed to grow to postconfluence over the course of 8–9 days. Similar to protein levels, there is a biphasic expression pattern with increasing levels of mRNA transcript as cells reached confluence around day 4, and decreasing levels as the cultured proceeded into postconfluence.

Biphasic expression of CXCL11 is not dependent upon calcium-dependent desmosome formation

To confirm that CXCL11 expression was not dependent upon the formation of desmosomes, and thus not a consequence of redifferentiation, the aforementioned experiment was repeated, but in low calcium media (∼0.09 mM calcium), a condition that prevents desmosome formation.19,35–38 While there was some accumulation of desmoplakin with time, both the total amount of protein and the amount accumulating in the SDS-soluble (saponin- and triton-insoluble) pool was considerably decreased compared to normal calcium cultures (Fig. 2D).

The pattern of CXCL11 expression in these low calcium cultures, however, grossly matched the biphasic pattern of expression seen in normal/high extracellular calcium-containing media. There was increased CXCL11 expression especially in cultures with cell densities within the 1,000–2,000 cells/mm2 range. As cellular density further increased, there was a decrease back to baseline. As in normal calcium conditions, the CXCL11 expression pattern was not proportional to time in culture.

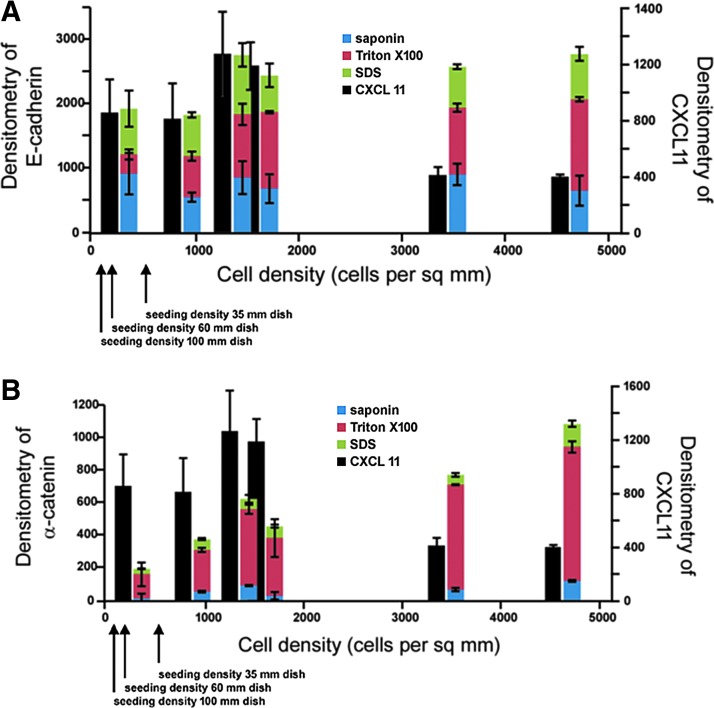

Expression of adherens junctions proteins, E-cadherin and α-catenin, was also analyzed by sequential detergent extraction to see if there was a correlation with adherens junctions formation (Fig. 3A, B). There was progressive accumulation of total amounts of adherens junctions proteins, E-cadherin and α-catenin, with both time in culture as well as increasing cellular density, but these changes did not correlate with the biphasic CXCL11 expression pattern.

Figure 3.

Sequential detergent extraction of E-cadherin and alpha-catenin. Equal numbers of HaCaT cells seeded on 35-, 60-, and 100-mm dishes and harvested after 48 h or 96 h of culture. Sequential detergent extraction with saponin (green), Triton X-100 (red), and SDS-containing buffer (blue) was performed. No major changes were observed correlating with CXCL11 (black) expression for (A) E-cadherin or (B) alpha-catenin in the different detergent pools in the two time points or at different confluencies by densitometry of western blot signal. Error bars represent standard error the mean.

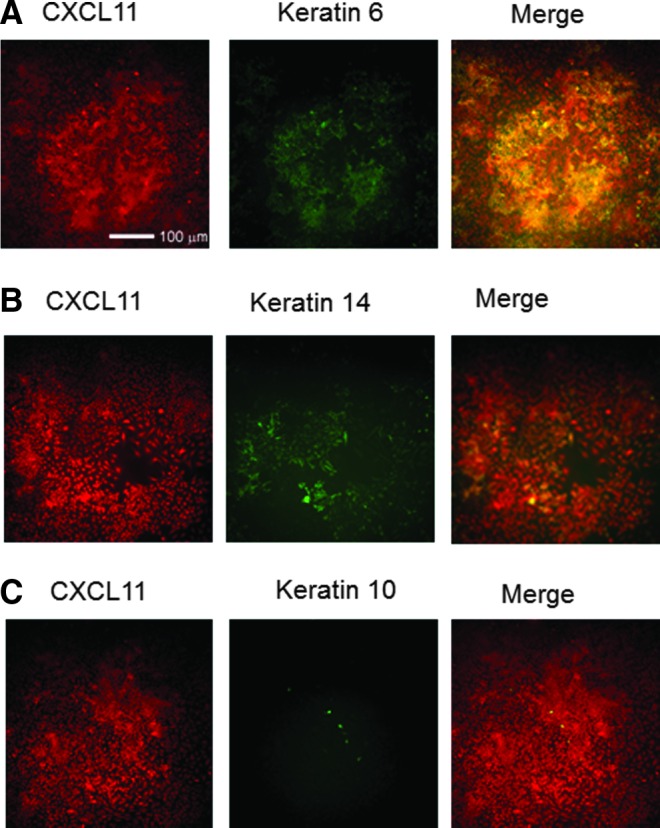

While CXCL11 expression did not correlate with organization of desmosomes and adherens junctions, there was an association with expression of some keratins (Fig. 4). CXCL11 expression showed strongest colocalization with expression of keratin 6, a keratin associated with hyperproliferative epithelia. There was also modest colocalization with keratin 14. While cells staining for keratin 10, a keratin expressed in the suprabasal epidermis, were rare within these HaCaT cell cultures, they were located in areas where cells were densely packed and where cells appeared to be stratified and lacked CXCL11 expression.

Figure 4.

Localization CXCL11 (red) staining in HaCaT cell culture correlated closely with keratin 6 expression (A), a marker of keratinocyte hyperproliferation and slightly with keratin 14 (B), a marker of basal keratinocytes. While there was very little keratin 10 expression in these cultures, a marker of keratinocyte differentiation (C), keratin 10-positive cells were localized in high cell density areas, where CXCL11 was also more highly expressed.

Discussion

This study investigated possible mechanisms that regulate CXCL11 expression in epithelial cells (A431) and keratinocytes (HaCaT) in an in vitro model system. Previous data from mouse and human in vivo models showed that CXCL11 expression in the wound and periwound area has a distinct spatial and temporal pattern.3–6 Specifically, there was increased CXCL11 expression along the basal layer of keratinocytes extending from uninjured keratinocytes near the edge of the wound and extending into the wound bed, but decreasing in intensity near the edge of re-epithelialization.

This pattern was, in large part, reproduced in the tissue culture model system presented in this study. A transient increase in CXCL11 secretion was also observed shortly after wounding in scratch-wounded A431 and HaCaT cell monolayers that dissipated after the scratch wounds re-epithelialized (Fig. 1G). Similar to what is seen in vivo, cellular proliferation within the scratch wound, as assessed by the Click-IT EdU Alexa 488 staining, is somewhat low within the region of migrating cells within the scratch wound until confluence is achieved. More mature monolayers took longer to close the scratch wound, however, CXCL11 secretion also occurred near the time of wound closure (data not shown).

Even in unwounded sparse culture, there was a similar CXCL11 expression pattern in outgrowing colonies. CXCL11 expression was elevated in areas where cellular density was highest (Fig. 1D). These regions corresponded with areas of high desmoplakin expression (Fig. 1C), suggesting areas where cells were differentiating and starting to form a strong, mechanically stable epithelium.20–24 However, when desmosome formation was inhibited by low-calcium culture conditions, the biphasic CXCL11 expression pattern persisted (Fig. 2C, D).

Instead of varying with time, CXCL11 expression is better correlated with cellular density (Fig. 2C). At both the 48 h and 96 h time points, the highest levels of CXCL11 expression were seen in cultures that were just achieving cellular confluency, whereas sparse cultures and densely compacted cultures had relatively low expression. Plotting the data with respect to cellular density revealed a biphasic pattern of expression with increasing levels between 1,000 and 2,000 cells/mm2, correlating with 90–100% confluency. Above 2,000 cells/mm2, as cells become more packed and more cuboidal, CXCL11 expression levels dropped progressively to baseline levels.

These findings were further supported by immunofluorescence analysis of cytokeratin expression in these cultures. CXCL11 expression was highest in keratinocytes expressing keratin 6 (Fig. 4), a cytokeratin characteristic of activated keratinocytes25–28,32,33 and keratin 14, a cytokeratin expressed in the basal layer of keratinocytes. Keratin-10, a marker of keratinocyte differentiation and most highly expressed in suprabasal keratinocytes, did not colocalize with cells expressing the highest levels of CXCL11. This again suggests that CXCL11 expression occurs during a period of time when activated; more migratory keratinocytes that express keratin 6 are transitioning into basal keratinocytes that express keratin 14.

A model of keratinocyte re-epithelialization is as follows: Wounding of mature epithelial monolayers results in a wave of desmosome remodeling that renders cells near the wound edge to lose calcium independence which presumably allows for desmosome dissociation or internalization.29,30 These activated keratinocytes become more migratory and enter into the wound bed.31 Perhaps as these migratory keratinocytes re-establish confluency and are able to return to their homeostatic state as marked by a switch from keratin 6/16 expression to keratin 5/14, CXCL11 secretion could serve to stimulate nearby activated keratinocytes to further migrate and seek out presumably nearby areas of wound bed to colonize. CXCL11 secretion could potentially also stimulate nearby fibroblasts and endothelial cells within the wound to begin contraction and neovascular pruning, respectively.

Since the CXCL11 expression pattern is even present in low calcium culture conditions, the up- and downregulatory signals are less likely dependent upon signaling through calcium-dependent intercellular junctions. Possible candidates could include tension of the cortical actin cytoskeleton, localization/regulation of the CXCL11 receptor CXCR3, establishment of cell–substrate connections through integrins, or signaling downstream of CXCL11-activated calpains. These ongoing studies lie beyond the scope of the present study, however, continued investigation of the CXCL11-CXCR3 signaling pathways during re-epithelialization will provide better understanding of cutaneous wound healing and possible targets for the treatment of dystrophic wounds and scars.

Innovation

A role of CXCL11/IP9/I-TAC in triggering the transition from the regenerative to the late resolution stage of wound healing has been demonstrated previously, but the physiological signals regulating the expression and secretion of this signal remain unknown. The timing of appearance suggests that confluence and/or keratinocyte communication may control expression of this chemokine in the context of epidermal wound healing. The basilar localization of the keratinocytes expressing CXCL11 suggests that this population, having migrated into the wound bed and re-established contact with the dermis, may undergo re-differentiation with a transient production of CXCL11.

Key Findings.

• Upregulation of CXCR3 ligand CXCL11 expression in keratinocyte cell line occurs near the time cellular confluency is achieved

• Downregulation of CXCL11 expression occurs in the postconfluent cultures suggesting that control of expression may be a function of cellular density

• Expression of CXCL11 does not appear to be associated with the differentiation state of the cells as biphasic expression of CXCL11 occurs despite prevention of desmosome formation using low calcium culture conditions.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CXCL11

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11, also known as I-TAC (interferon-inducible T-Cell Alpha Chemoattractant), IP-9 (interferon-inducible protein)

- CXCR3

chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3

- CXCL9

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9, also known as MiG

- CXCL10

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10, also known as IP-10

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from NIH (GM63569, GM69668, and K08 GM095917-04). The authors thank members of the Wells Laboratory for constructive comments and suggestions. The VA Pittsburgh Health System provided support in kind. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest in terms of the materials included herein.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

No competing financial interests exist. The content of this article was expressly written by the author(s) listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Arthur C. Huen, MD, PhD is an instructor in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh Department of Dermatology and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), where he investigates late-stage cutaneous wound healing. His clinical practice includes general dermatology, chronic cutaneous wound clinic, as well as hospital consultation services. Archana Marathi, MS is a research laboratory technician currently with the Department of Rheumatology at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, previously with the University of Pittsburgh Department of Dermatology. Peter K. Nam, BS is a research laboratory technician in the Department of Dermatology, University of Pittsburgh. Alan Wells, MD, DMSc is the Executive Vice-Chairman of the Section of Laboratory Medicine, Medical Director for the UPMC Clinical Laboratories, and the Thomas Gill III Professor of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- 1.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med 1999;341:738–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babu M, Wells A. Dermal-epidermal communication in wound healing. Wounds 2001;13:7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates CC, et al. Lack of CXC chemokine receptor 3 signaling leads to hypertrophic and hypercellular scarring. Am J Pathol 2010;176:1743–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates CC, et al. ELR-negative CXC chemokine CXCL11 (IP-9/I-TAC) facilitates dermal and epidermal maturation during wound repair. Am J Pathol 2008;173:643–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yates CC, et al. Delayed reepithelialization and basement membrane regeneration after wounding in mice lacking CXCR3. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:34–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yates CC, et al. Delayed and deficient dermal maturation in mice lacking the CXCR3 ELR-negative CXC chemokine receptor. Am J Pathol 2007;171:484–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satish L, Yager D, Wells A. Glu-Leu-Arg-negative CXC chemokine interferon gamma inducible protein-9 as a mediator of epidermal-dermal communication during wound repair. J Invest Dermatol 2003;120:1110–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiraha H, et al. IP-10 inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced motility by decreasing epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated calpain activity. J Cell Biol 1999;146:243–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen FD, et al. Epidermal growth factor induces acute matrix contraction and subsequent calpain-modulated relaxation. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodnar RJ, et al. IP-10 induces dissociation of newly formed blood vessels. J Cell Sci 2009;122(Pt 12):2064–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar RJ, Yates CC, Wells A. IP-10 blocks vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell motility and tube formation via inhibition of calpain. Circ Res 2006;98:617–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulesz-Martin M, et al. Pemphigoid, pemphigus and desmoplakin as antigenic markers of differentiation in normal and tumorigenic mouse keratinocyte lines. Cell Tissue Kinet 1989;22:279–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrod DR, et al. Hyper-adhesion in desmosomes: its regulation in wound healing and possible relationship to cadherin crystal structure. J Cell Sci 2005;118(Pt 24):5743–5754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrod D, Kimura TE. Hyper-adhesion: a new concept in cell-cell adhesion. Biochem Soc Trans 2008;36(Pt 2):195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrod DR, et al. Pervanadate stabilizes desmosomes. Cell Adh Migr 2008;2:161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown S, Levinson W, Spudich JA. Cytoskeletal elements of chick embryo fibroblasts revealed by detergent extraction. J Supramol Struct 1976;5:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forman DS, Brown KJ, Livengood DR. Fast axonal transport in permeabilized lobster giant axons is inhibited by vanadate. J Neurosci 1983;3:1279–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollenbeck PJ. The distribution, abundance and subcellular localization of kinesin. J Cell Biol 1989;108:2335–2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennings H, et al. Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of mouse epidermal cells in culture. Cell 1980;19:245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong DK, et al. Haploinsufficiency of desmoplakin causes a striate subtype of palmoplantar keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallicano GI, et al. Desmoplakin is required early in development for assembly of desmosomes and cytoskeletal linkage. J Cell Biol 1998;143:2009–2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt A, et al. Desmosomes and cytoskeletal architecture in epithelial differentiation: cell type-specific plaque components and intermediate filament anchorage. Eur J Cell Biol 1994;65:229–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skerrow CJ, Matoltsy AG. Chemical characterization of isolated epidermal desmosomes. J Cell Biol 1974;63:524–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fey EG, et al. Epithelial structure revealed by chemical dissection and unembedded electron microscopy. J Cell Biol 1984;99:203s–208s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansbridge JN, Knapp AM. Changes in keratinocyte maturation during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol 1987;89:253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzalupo S, Wawersik MJ, Coulombe PA. An ex vivo assay to assess the potential of skin keratinocytes for wound epithelialization. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:866–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wojcik SM, Bundman DS, Roop DR. Delayed wound healing in keratin 6a knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:5248–5255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong P, Coulombe PA. Loss of keratin 6 (K6) proteins reveals a function for intermediate filaments during wound repair. J Cell Biol 2003;163:327–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura TE, Merritt AJ, Garrod DR. Calcium-independent desmosomes of keratinocytes are hyper-adhesive. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:775–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarin D, Croft CB. Ultrastructural features of wound healing in mouse skin. J Anat 1969;105(Pt 1):189–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danjo Y, Gipson IK. Actin ‘purse string’ filaments are anchored by E-cadherin-mediated adherens junctions at the leading edge of the epithelial wound, providing coordinated cell movement. J Cell Sci 1998;111(Pt 22):3323–3332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernot KM, Coulombe PA, McGowan KM. Keratin 16 expression defines a subset of epithelial cells during skin morphogenesis and the hair cycle. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:1137–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DePianto D, Coulombe PA. Intermediate filaments and tissue repair. Exp Cell Res 2004;301:68–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothnagel JA, et al. The mouse keratin 6 isoforms are differentially expressed in the hair follicle, footpad, tongue and activated epidermis. Differentiation 1999;65:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brysk MM, Miller J, Walker GK. Characteristics of a human epidermal squamous carcinoma cell line at different extracellular calcium concentrations. Exp Cell Res 1984;150:329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denefle JP, Lechaire JP. Calcium-modulated desmosome formation and sodium-regulated keratinization in frog skin cultures. Tissue Cell 1986;18:285–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattey DL, Garrod DR. Calcium-induced desmosome formation in cultured kidney epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 1986;85:95–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattey DL, Garrod DR. Splitting and internalization of the desmosomes of cultured kidney epithelial cells by reduction in calcium concentration. J Cell Sci 1986;85:113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Q, Dhir R, Wells A. Altered CXCR3 isoform expression regulates prostate cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol Cancer 2012;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huen AC, Park JK, Godsel LM, et al. Intermediate filament-membrane attachments function synergistically with actin-dependent contacts to regulate intercellular adhesive strength. J Cell Biol 2002;159:1005–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]