Abstract

Ambient-pressure photoelectron spectroscopy (APPES) and microscopy are at the frontier of modern chemical analysis at liquid-gas, solid-liquid and solid-gas interfaces, bridging science and engineering of functional materials. Complementing the current state-of-the art of the instruments, we survey in this short review several alternative APPES approaches, developed recently in the scanning photoelectron microscope (SPEM) at the Elettra laboratory. In particular, we report on experimental setups for dynamic near-ambient pressure environment, using pulsed-gas injection in the vicinity of samples or reaction cells with very small apertures, allowing for experiments without introducing additional differential pumping stages. The major part of the review is dedicated to the construction and performance of novel environmental cells using ultrathin electron-transparent but molecularly impermeable membranes to isolate the gas or liquid ambient from the electron detector operating in ultra-high vacuum (UHV). We demonstrate that two dimensional materials, such as graphene and derivatives, are mechanically robust to withstand atmospheric - UHV pressure differences and are sufficiently transparent for the photoelectrons emitted from samples immersed in the liquid or gaseous media. There are many unique opportunities for APPES using X-rays over a wide energy range. We show representative results that illustrate the potential of these ‘ambient-pressure’ approaches. Combined with the ca 100 nm lateral resolution of SPEM, they can overcome the pressure gap challenges and address the evolution of chemical composition and electronic structure at surface and interfaces under realistic operation conditions with unprecedented lateral and spectral resolution.

Keywords: ambient pressure XPS, graphene membranes, environmental cell, microscopy

1. Introduction

Fundamental understanding and control of processes occurring at surfaces and interfaces can guide the design and optimization of catalysts and materials used in chemical industry, energy and electronic devices and also will respond to many open questions in biomedical research. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for detailed in-situ surface analyses of functional matter under realistic working conditions. Only in the last decade the most powerful surface sensitive method, Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES), also known as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA),[1] has really overcome the pressure gap. Today Ambient Pressure PES (APPES) allows for in-situ PES experiments that were a dream half a century ago. The first APPES attempts in liquid ambient were made by Kai Siegbahn’s group in the early 1970s, followed by the exploration of a variety of experimental approaches, such as liquid beams (jets [2–4] or flying droplets [5]), and wetted specimens [6]. These efforts culminated recently by implementation of differentially pumped electron analyzers, using both laboratory X-ray sources [7–11] and synchrotron radiation facilities [12–14]. The progress of APPES with multiple applications in studies of solid/gas and solid/liquid interfaces, comprehensively reviewed in refs [15],[16], and the fast growing number of researchers using these instruments are clear demonstration of the impact and maturity of this methodology. Using synchrotron light for APPES has several advantages, namely the signal gain due to the higher photon flux, the X-ray energy tunability that enables a high ionization cross section for the electronic levels under consideration and adjustable depth sensitivity by controlling the kinetic energy of the emitted electrons.

The tunability of synchrotron light also allows another spectroscopy that complements PES, namely X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). This technique is based on monitoring the transmitted photons or the total emitted electron or fluorescence signal as a function of energy of the incident photon beam [17]. XAS spectrum has two distinct parts: the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), covering the energy range up to 50 eV above the absorption edge of the element, and the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) region above this photon energy. The XANES provides chemical characteristics based on the X-ray induced resonant electronic transitions from the core levels into unfilled electronic states, governed by the well-established selection rules, and serves as a site-specific probe of local charge state, coordination, and magnetic moment of absorbing atoms. Compared to XPS with soft X-rays, which is extremely surface sensitive, complementary XANES spectroscopy measuring total electron yield increases the probing depth to 10 nm, so that one can probe the sub-surface region and buried interfaces as well. Using synchrotron light with circular (left-right) or linear (vertical-horizontal) polarization adds information on average magnetic moment and symmetry of the chemical bonds.

However, the currently operational APPES instruments, both in laboratories and synchrotron facilities, are limited in lateral resolution and cannot respond to the increasing needs of exploring surface and interface properties at submicron and nanoscopic scales, where inhomogeneity in composition and/or morphology is very common in all technologically important materials. More than two decades ago, the demand to characterize the materials at their natural length scales has pushed the development of two major types of X-ray photoelectron microscopies operated with synchrotron light [18–21] and it is appealing to adapt such instruments also for working at ‘ambient’ pressures. However, such adaptation is practically impossible for the X-ray imaging Photo Emission Electron Microscope (XPEEM) [19,20] that uses electron projection optics to produce a magnified image on the detector plane. These microscopes can reach a lateral resolution better than 10 nm, but the high fields at the sample (of the order of 106 V/m to 107 V/m), needed for collection efficiency and lateral resolution, exclude working at ambient pressures. The other photoelectron microscopy type, X-ray scanning photoelectron microscope (SPEM) [18,19,21], can be described as a classical PES instrument with photon focusing optics forming an X-ray microprobe. It can reach the lateral resolution of 50 nm when using zone plates (ZPs) as focusing elements. However, the ZP optical set-up, namely the short distance between the focusing system and the sample together with the grazing accepting geometry of the electron analyzer, imposes severe geometrical constraints at soft X-rays energies that need to be solved.

In this paper, after an overview of several routes to further the APPES methodology, we discuss the set-ups recently developed and tested at the Elettra laboratory that also overcome the aforementioned constraints for SPEM operation at ambient pressure. The membrane-based approaches suitable for all type of instruments with electron detection are extensively discussed, including information on the recent progress in membrane characterization and fabrication technology.

2. APPES concepts

2.1 Differentially pumped APPES

A key feature of the APPES technique is performing experiments with samples exposed to their working environment, e.g. a gaseous atmosphere at elevated pressure or a liquid environment. The major problem to be solved in construction of APPES instrument is the short inelastic mean free path (IMFP) of photoelectrons (PEs) travelling in dense phases. Three possible strategies, sketched in Figure 1, can be used to minimize the photoelectron elastic and inelastic scattering and thus to meet the requirements of APPES experiments.

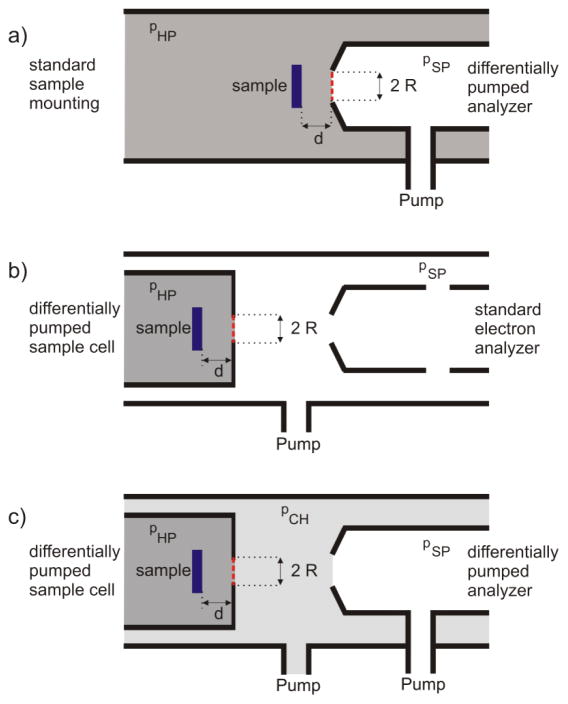

Fig. 1.

Possible arrangements of electron spectrometer and sample environment for APPES. a) Chamber with conventional sample mounting attached to a differentially pumped electron analyzer with an aperture of radius R placed at the analyzer entrance. b) Conventional electron analyzer combined with a differentially pumped sample cell and c) Combination of a differentially pumped sample cell with a differentially pumped electron analyzer. The red-dashed lines indicate the positions, where exchangeable electron-transparent membranes may be used in order to isolate the nearby compartment.

In the first set-up, the differentially pumped analyzer is attached to the chamber hosting a conventional sample holder (Fig. 1a). As sketched in the figure, an aperture of radius R, placed at the entrance of the electron analyzer lens system at a distance d from the sample, acts as a pressure reducing orifice between the sample environment (pHP) and the first pumping stage of the spectrometer (pSP). Obviously, decreasing R will increase the pressure difference between the sample environment and the electron analyzer, but at a given sample distance d, this also cuts the acceptance angle of the spectrometer, reducing the detection efficiency. Thus, a compromise between detection efficiency and the inelastic mean free path of electrons in the dense medium has to be found, which determines the achievable pressure in the sample area. The distance, d, between the sample and the aperture should not be smaller than d ≈ 2R, as it ensures a local pressure at the sample surface comparable (≈95 %) to the overall pressure pHP. It should be noted that the use of focused photon beams allows for smaller apertures without a significant signal loss. Depending on the X-ray beam spot size, the analyzer dimensions and the number of differential pumping stages, the achievable pressure at the sample in laboratory instruments can be 1 hPa [10] reaching even 30 hPa in the recent report [11]. Synchrotron-based APPES systems operate at pressures of the order of 10 hPa [15,12] reaching pressures higher than 100 hPa in recent apparatus using an aperture size of 50 μm.[22]

The second approach, sketched in Fig. 1b, combines a standard (non-differentially pumped) electron analyzer with a reaction cell, which has its own gas inlet and differential pumping system. Here, the aperture of the cell in front of the sample provides the required pressure reduction between pHP and pSP with the same trade-offs as the ones of the first concept, described above. It should be noted that the use of focused photon beams is beneficial for both concepts, because it allows for higher pressures via placing smaller apertures. As reported in section 3.1, the submicrometer photon beam at the ESCA microscopy beamline at Elettra enables measurements at pressures up to 1 hPa inside such reaction cells.

As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the two set-ups can also be combined, resulting in a compartment at an intermediate pressure pCH (pHP > pCH > pSP). This combination is advantageous, since the walls of the surrounding vacuum chamber are not exposed to high pressure, which allows for quick switching between high pressure and UHV conditions.[14,16] In order to obtain a sufficiently intense photoelectron signal, the differentially pumped sample cell is placed close to the electron analyzer entrance. As will be discussed in the following section, membrane-based reaction cell concepts allow for moving the sample cell away from the analyzer entrance, which can be beneficial in many applications.

2.2 Membrane-based APPES

Another concept complementing differential pumping in APPES is based on use of electron transparent but molecular-impermeable membranes to separate the sample compartment from the UHV of the electron analyzer. Development of such a PES-through-membrane approach is inspired by the successful photoelectron spectroscopy and microscopy of buried interfaces for a wide range of excitation energies spanning ultraviolet (UV) [23], soft X-rays [24] to hard X-rays [25,26]. The membrane can be considered as an overlayer with a thickness comparable to the IMFP, so that the signal from the immersed sample is directly related to the classical signal attenuation by overlayer films in surface science [27]. Thus, the attenuation due to inelastic electron scattering by a membrane of thickness d can be evaluated using known databases [28,27] and software [29], discussed in more details in section 3.3. For example, the IMFP of photoelectrons with energies of a few hundred eV is of the order of 1 nm inside the membrane material. Assuming that 90 % loss of PES signal from the encapsulated object is acceptable, a 1 nm thick membrane sealing an environment at atmospheric pressure requires the sample surface to be placed at a distance of 1 μm below the membrane, which is sufficient to maintain a thermodynamic equilibrium with the ambient. It is important to note that the minimal membrane thickness and the sample-to-membrane distance limit can be further relaxed if hard X-rays are used, since the high kinetic energies photoelectrons have longer IMFPs [30].

The use of electron transparent membranes can be advantageous to the aforementioned differential pumping approaches: sealing with a membrane is indicated by a red dashed line for the three set-ups illustrated in Fig. 1. In all three cases, even if the membranes are imperfect and not 100 % impermeable, the limitation on the maximum achievable sample environment pressures can be greatly relaxed, as described in the following:

The sample area from which photoelectrons are collected is not limited anymore by the size of pressure limiting apertures and can therefore be significantly increased. In addition, much larger pressure differentials can be allowed for all APPES concepts sketched in Fig. 1. For example, as long as a molecular flow regime is sustained, it should still be possible to increase the pressure differential by two orders of magnitude even if 1 % of the membrane area is holey [31].

The restriction d ≈ 2R is not anymore valid when using a membrane, since the electron path inside the dense medium depends only on the sample-membrane distance. This relaxed constraint will allow for denser phases in the sample area, while keeping the same spectral quality simply by reducing the distance to the analyzer.

Using arrays of micro-membranes rather than a single membrane (see section 5), macroscopic sample areas can be explored using the setup sketched in Fig. 1b. Hence, high quality APPES studies can be done using standard laboratory-based equipment.

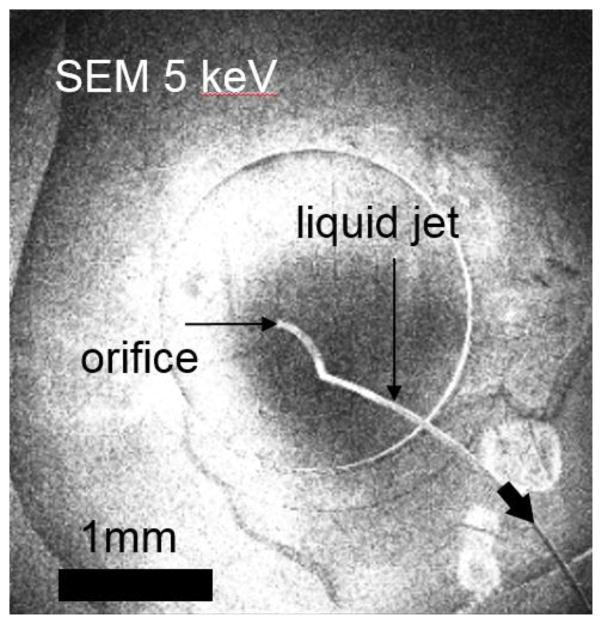

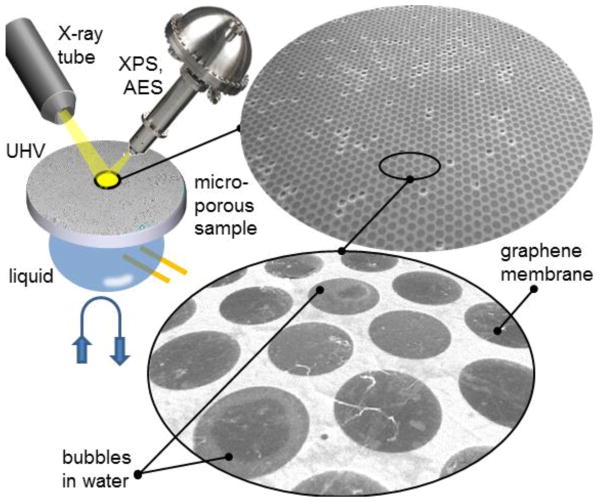

Combining a membrane-sealed sample cell with a differentially pumped analyzer can boost the performance of existing APPES instrumentation as outlined in the points 1)-3). The additional advantage of this combination (see Fig. 1c) is that the sample cell can be easily repaired after a membrane failure. In addition, the membrane-sealed cell may be placed further away from the analyzer entrance, thereby protecting the delicate electron lens system in case of membrane failure. This advantage is especially important when dealing with samples in a liquid environment, where membrane failures may lead to ejection of a liquid jet (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SEM movie snapshot of a liquid jet ejecting into the vacuum chamber from a sealed liquid cell upon disruption of a graphene membrane. The ejection continues until the Laplace pressure at the orifice equilibrates with the pressure differential between the vacuum and interior of the cell.

It should be noted that all of the above considerations apply to APPES of liquids or samples in a liquid environment, assuming that any liquid leakage and its related partial pressure do not exceed the capability of the pumping system. Since this problem has to be avoided, gas tight membranes of maximum mechanical, chemical and radiation stability are essential for such studies and are still the objective of our research. The recent progress in development and characterization of highly electron transparent membranes is discussed in sections 3.3 and 4 of this paper.

3. APPES microscopy

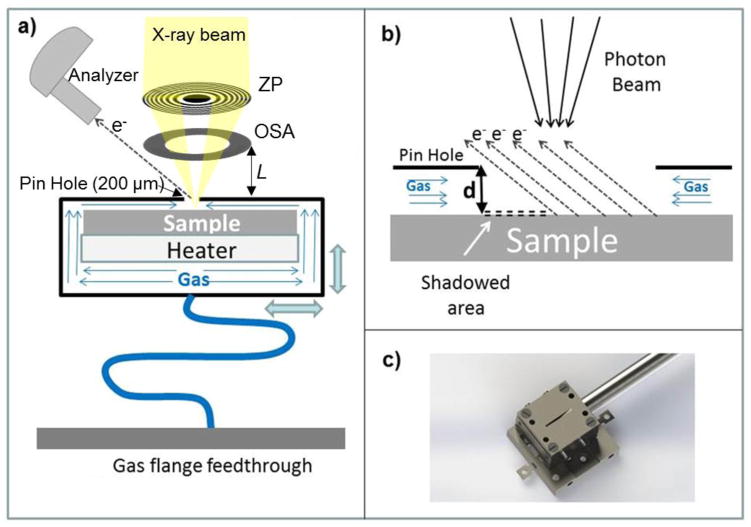

As noted in the introduction, scanning photoelectron microscopes can be adapted to ambient pressure experiments accommodating constraints imposed by the presence of focusing optics, sample scanning system, and grazing incidence geometry of the electron analyzer (see the sketch in Fig. 3a). The best beam demagnification is achieved by a focusing system placed along the X-ray beam normal to the sample and consisting of ZP diffractive optics followed by an order sorting aperture (OSA) for blocking the undesired high order diffraction. In APPES, one should carefully evaluate the constraints imposed by the distance L between the sample and the OSA (Fig. 3a). This distance depends on several parameters and increases with increasing X-ray energy, ZP diameter and ZP outermost zone width. The usual ZP to sample distance is of the order of 3mm to 10 mm using soft X-rays, since the outermost zone width that determines the microprobe size (lateral resolution) should be in the few tens nm range and microfabrication of such a ZP with diameter beyond 300 μm is challenging. The presence of the OSA restricts access to the sample even more and it is impossible to realize the classical differentially pumped analyzer APPES geometry where the sample to analyzer distance is usually less than 1 mm. Placing the X-ray focusing set-up at a grazing incidece angle with respect to the surface normal, as used in classical PES, introduces severe distortions in the microprobe dimensions on the sample and does not resolve the sample-analyzer distance issue completely. However, ambient pressure SPEM (AP-SPEM) can be performed using electron transparent membranes to separate the sample environment from the electron and/or X-ray optics, as we have already demonstrated [32,33] and as is discussed in section 3.3. Additionally, we have developed two other simpler set-ups, a reaction cell using only a small orifice for probing the sample (section 3.1) and a dynamic high pressure gas injection system (section 3.2) that can partially overcome the limitations imposed in ZP-based SPEMs when working at near-ambient pressures. These different set-ups were designed and constructed to fit to the SPEM instrument, operated at the ESCA microscopy beamline of the Elettra synchrotron research center [34]. These approaches are also applicable to other photon-in/electron -out or electron-in/electron-out instruments of this type.

Fig. 3.

(a) Sketch of the SPEM set-up with the reaction cell and its main components. (b) Large scale sketch illustrating the probe-sample area. In order to illustrate the shadowing effect, the distance d is expanded. (c) Photo of the cell mounted on the sample holder which can be inserted in the scanning unit of the SPEM.

3.1 Reaction cells for SPEM

The general concepts for construction of reaction cells are not new: retractable cells bridging near ambient pressure up to 30 hPa and UHV have already been offered by the companies providing laboratory XPS instruments [11]. The specific approach used in the cell design for SPEM further exploits the advantage of a focused X-ray beam. The SPEM reaction cell, illustrated in Fig. 3a), is vacuum sealed and has a small pinhole of 200 μm diameter on the front plate. The 50 nm to 100 nm wide X-ray microprobe illuminates the sample placed at a distance of 30 μm to 40 μm behind the pinhole as shown in Fig 3b. For the axes of the electron analyzer at 60° with respect to X-ray beam, such a small distance allows for collection of photoelectrons from a sufficiently large sample area without significant shadowing effects. The reactive gases were controllably delivered into the cell via flexible tubing, connected to a flange with a needle valve. The pumping speed of the vacuum chamber permits achieving pressures up to 1 hPa inside the cell, while keeping the background pressure of the SPEM chamber below 10−5 hPa (upper safe limit for performing photoelectron spectroscopy). An encapsulated heater, attached on the rear side of the sample, is used to vary the sample temperature in the range 300 K to 773 K. The cell assembly was mounted on a sample holder (Fig. 3c), attached to the x-y scanner, which was used in the SPEM imaging mode and also for fine positioning at selected locations in the micro-spectroscopy mode. All parts of the cell, including the heater and the thermocouple feedthroughs, were made of UHV compatible materials to avoid parasitic degassing inside the enclosure upon heating.

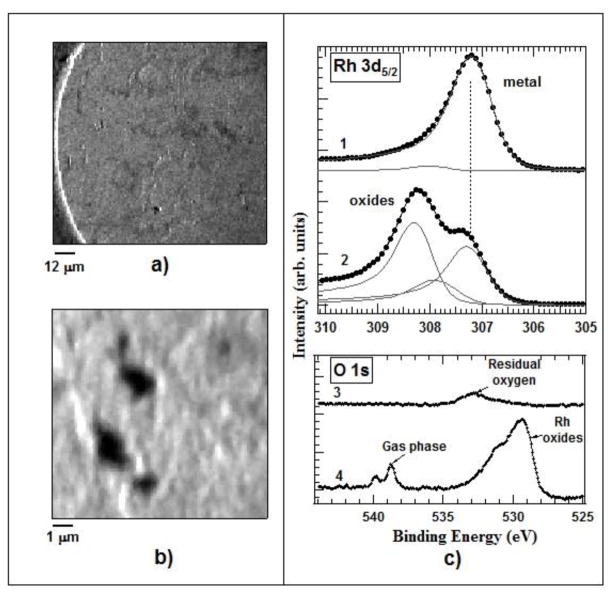

The cell performance was tested using the well-known oxidation and reduction of a metal surface by measuring the evolution of Rh 3d and O 1s core levels acquired from an unpolished Rh foil exposed to oxygen and hydrogen. Figures 4a) and 4b) shows large and small scale images of the Rh foil, mounted inside the high pressure cell, acquired with the photoelectron analyzer energy window tuned to the Rh 3d5/2 core level. The images represent the lateral variations of the photoemission signal integrated over the whole energy window, including also the background. Under these settings the observed darker and brighter features are topographic contrast, i.e. local enhancement or attenuation of the emitted photoelectrons, generated by the structural imperfection of the Rh surface [35]. These well-resolved structures prove that the typical submicron resolution of the SPEM instrument is preserved, i.e., the cell setup does not deteriorate the spatial resolution of the microscope.

Fig. 4.

(a) 100×100 μm2 Rh 3d5/2 image of the Rh foil. (b) 12×12 μm2 Rh 3d5/2 images of the Rh foil. (c) Rh 3d5/2 and O1s microspot spectra of the Rh foil before - 1), 3) and after oxidation - 2), 4). The measurements were made with a photon energy of 650 eV.

The lineshape of the top Rh 3d5/2 spectrum 1 in Fig. 4c) is typical for a sample exposed shortly to air before being introduced into the cell, where it was annealed at 573 K in the ambient of 1 hPa of H2(g) for 60 min in order to reduce the formed oxide. The spectrum, deconvoluted by using Doniach-Sun-jich functions (black solid lines), reveals a dominant metallic Rh component at a binding energy (BE) of 307.2 eV and a tiny peak at 307.8 eV, indicative of the presence of residual sub-stoichiometric surface oxides.[36] This result is clear evidence that the annealing at 1 hPa H2 exposure had effectively reduced the sample and had also removed the C contaminants, which would not be possible for H2 pressures of max 5 × 10−5 hPa allowed in the SPEM chamber. The same surface was then exposed to 1 hPa O2 for 30 minutes, keeping the temperature of the sample at 573 K. The measured Rh 3d5/2 spectrum after our oxygen treatment (spectrum 2 in the Rh3d5/2 panel of Fig. 4c) is dominated by a new peak located at 308.3 eV BE, corresponding to Rh2O3.[37] The observed changes in the Rh 3d and O 1s spectra after oxidation are in fair agreement with prior results for Rh films and Rh polycrystalline foils, oxidized at ambient pressures where the observed two components were attributed to of Rh2O3 and RhO2/RhOOH species.[38,39]

Clear demonstration that the sample inside the cell was exposed to an O2 pressure of the order of hPa, required for advanced Rh oxidation, are the O 1s core level spectra recorded before and during exposure of the Rh foil to O2. Spectrum 3 in Fig. 4(c), measured after the initial treatment in H2, appears as a tiny broad feature peaked at ≈533 eV, matching a residual suboxide.[37] This is evidenced by the small high BE component in the corresponding Rh 3d5/2 spectrum 1 as well. As in the case of the Rh 3d5/2 spectrum, the line shape and position of the O 1s spectrum drastically changes when the Rh sample is exposed to 1 hPa O2. As clearly evidenced by spectrum 4, two new distinct doublet spectral features appear. The more intense doublet is dominated by a component located at ≈ 529.5 eV and the second weaker one at ≈ 531.5 eV. The second nicely resolved doublet within the 538.5 eV to 540 eV range corresponds to gas-phase oxygen molecules inside the cell, ionized by the impinging X-rays. The line shape and intensity of the O 1s spectral feature from the gas phase oxygen confirms that the cell allows hPa pressure levels to be reached. The Rh thus undergoes oxidation that cannot occur under high vacuum conditions [21].

3.2 Dynamic pressure system

The dynamic ‘high’ pressure approach (DHP) is based on the control of an amount of pulsed gas, injected in the vicinity of the sample, without exceeding the global pressure limits required for the SPEM operation [40]. The local pressure around the sample is controlled by fine tuning of the spatial and time profile of a collimated gas jet, directed towards the sample. In the DHP set-up, sketched in Fig. 5a), the gas pulsed jet is formed by a thin needle, avoiding any interference with the X-ray optic system and electron analyzer.

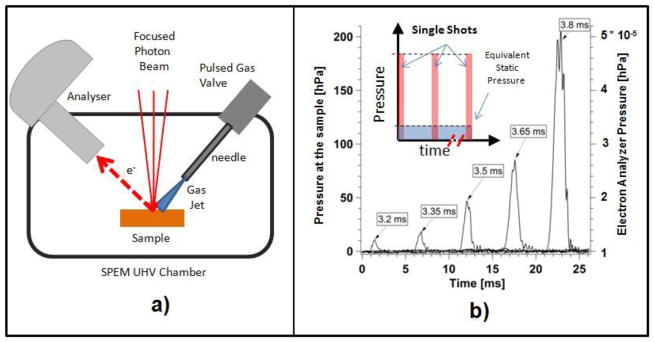

Fig. 5.

(a) Sketch of the DHP set-up adapted to the SPEM apparatus. (b) Time profiles of the pressure values at the sample (left axis) and inside the electron analyzer (right axis) for different pulse durations of a pulsed valve fed by an O2 gas pressure of 350 kPa. The insert illustrates the working principle of the DHP approach.

The insert in Fig. 5b) shows a sketch of the time profile of the pressure pulses at the sample. The series of gas jet shots at a fixed repetition rate and duration are obtained by using a computer controlled pulse valve. Each pulse generates a short burst of pressure at the sample (up to few hundreds hPa) confined in a small volume. If the duration and the repetition rate of the shots are properly tuned, the global background pressure does not exceed the limits imposed by the pumping speed of the vacuum system. In order to achieve the desired control of the gas pulses, a valve with sub-millisecond temporal response is needed. The valve/needle configuration is designed to eliminate any possible dead volume, in order to reduce the time for recovering the background pressure after each pulse. Figure 5b) shows the measured time profiles of the pressure values at the sample and inside the electron analyzer, using 350 kPa O2 gas pressure behind the pulsed valve. One can see that for a 200 hPa oxygen pulse and repetition rate of 0.35 Hz the global pressure in the vacuum chamber remains in the 10−5 hPa range. The data show that under these conditions, the global pressure recovers very fast to its standard UHV level.

The performance of the DHP system was tested by monitoring the oxidation of Ru, another extensively studied metal. A polycrystalline unpolished Ru sample with an average crystal grain diameter of 1 μm to 10 μm was first cleaned by high temperature annealing using alternating cycles of H2 and O2 ambient. Figure 6 (a) and (b) show the Ru images taken after cleaning by acquiring the photoelectrons emitted in the energy window of the Ru 3d5/2 spectrum.

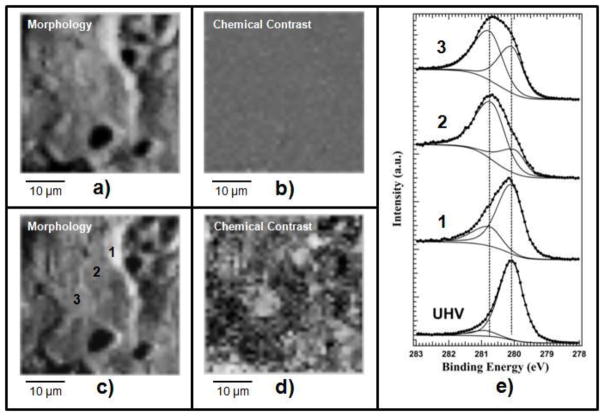

Fig. 6.

(a) and (c) Raw Ru images of clean and oxidized surface, respectively, measured with the analyzer tuned to the Ru 3d5/2 energy window, where the topography obscures the chemical contrast. (b) and (c) Ru chemical images obtained after removal of the topography contribution from (a) and (c), respectively. (e) Ru 3d5/2 spectra taken before (UHV) and after oxidation in different positions 1, 2, 3, as indicated in image (c). Oxidation conditions: pulse duration 3.2 ms, repetition rate of 0.35 Hz and O2 pressure behind the valve of 350 kPa. The data acquired from the oxidized surface were taken after 600 pulse shots.

The Ru 3d5/2 spectrum of the resultant clean surface, labeled as “UHV” in Fig. 6 (e), confirms that the metallic Ru component is the dominant feature. As in the case of the Rh foil (see Fig. 4) the contrast of the Ru image (a) is exclusively generated by the surface topography and outlines the grainy structure of the Ru surface, which obscures the true chemical contrast. By processing the clean surface Ru image to remove the topographic artefacts,[35] we obtained the image (b) showing an uniform contaminant-free Ru surface. The Ru sample kept at 790 K was oxidized in-situ using the O2 pulses provided by the DHP system. The Ru 3d5/2 image after oxidation (c) appears similar to the one before oxidation, since again the topography dominates the contrast. However, taking Ru 3d5/2 spectra in different positions, labeled as (1), (2), (3) we have clear evidence of inhomogeneous oxidation (see spectra 1, 2, 3 in Fig. 6(e)). The difference in the line shape of the three spectra reflects the different weight of the oxide component, which indicates structural dependence of the oxidation rate. The most intense oxide component is present in region (2) while it is the least intense in the region (1)[41]. Indeed, after removing the dominant topographic contrast we obtained the chemical map (d) confirming the inhomogeneity in the oxide lateral distribution (the darker areas corresponds to a lower oxidation state where the Ru oxide component is weaker. Comparing (c) and (d) one can also find some correlation between the chemical state and individual surface grains.

Further proof of the good performance of the DHP system was made by oxidizing a Silicon (111) surface and comparing the oxidation time evolution with that obtained by exposing the surface to a static pressure. The results (not shown) have demonstrated that the oxidation of the Si (111) sample at the DHP conditions is equivalent to a static case, where the pressure is kept between 10−3 hPa and 10−2 hPa, about 3 orders of magnitude higher than the maximum gas pressure allowed for the photoemission system in operando. The DHP system has already been successfully used for: (i) an in-situ monitoring of the chemical evolution of the electrode material of Ni|YSZ|Mn solid oxide fuel cell occurring in a H2 + O2 or CH4 + O2 ambient [42,43] and (ii) an in situ study of the polymer-exchange membrane fuel cell under polarization [44].

3.3. Membrane based approaches for the SPEM

Enclosed cells with SiN, SiO2 membranes have routinely been used for in situ X-ray absorption and transmission [45–50] spectroscopy. Since the membranes thickness capable to withstand 100 kPa atmospheric pressure differential exceeds 10 nm, they can be penetrated only by photoelectrons with high kinetic energies, as has been demonstrated recently for APPES with hard X-rays [30,51]. The limitations imposed by thickness of SiN and SiO2 membranes have been overcome by novel two-dimensional materials, such as graphene (G), graphene oxide (GO), hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) etc., which are electron transparent even for low energy photoelectrons, are molecularly impermeable, and have a record high mechanical strength making them ideal for APPES with soft X-rays [32,33]. In the following sections, we review our recent activities in fabrication and characterization of the electron transparent membranes tested with the SPEM operated at the ESCAmicroscopy beamline of the Elettra synchrotron light source [34].

3.3.1 Fabrication of high quality suspended graphene-based membranes

Graphene oxide (GO) was the first 2D material tested as an electron transparent window for APSPEM and SEM environmental cells (E-cells). GO membranes are attractive due to well-developed high yield chemical exfoliation protocols coupled with its large scale liquid processability of GO colloids (see recent review [52] and references therein). Due to their amphiphilic properties, GO flakes segregate at air-water, water-solid interfaces and easily form controllable membranes when using Langmuir-Blodgett (LB) or simple drop casting methods [32,53–57]. As prepared, the GO membranes made of interlocked GO flakes have selective permeation properties promoting the intercalation and diffusion of water between stacked GO flakes that makes them excellent filtering media [55,58,59]. To make these GO membranes suitable for APPES one can adopt the following strategies: (i) prepare GO electron transparent windows which are made of an individual single (or multilayer) GO flake; (ii) use of a GO membrane window which has less than one percolating channel for water. Since the amount N of percolating channels over an orifice of diameter D scales as N~(D/L)2 (here L is the average size of the GO flake) [55], one can make a molecularly impermeable membrane when D<L. In spite of the fact that GO flakes can be as large as hundreds of microns, the practical size of the orifice is below 10 microns due to the limited mechanical stability of the membrane under 100 kPa differential pressure.

Performing comparative tests with GO and graphene (G) membranes [32,33] (see section 3.3.2) we found that GO are less appealing as a membrane material for liquid APPES for the following reasons. First, as already mentioned above, GO can be water permeable if the size of the electron transparent window exceeds the average size of an individual GO platelet. Second, the thickness of the dip coated or drop casted GO membranes cannot be reliably controlled. Third, GO is non-conductive so that PES measurements require an energy reference. Finally, we found that GO is prone to photo-reduction under focused X-ray beams. Hence, graphene based membranes, being mechanically extremely robust, chemically stable, [60,61] easier to handle [62] and electrically conductive,[63] are much better choice. The superior performance of graphene membranes makes them appealing, but the fabrication of high quality suspended G membranes of larger size needs further development. In the following, we discuss the recent progress and the problems to be solved for improving the quality of fabricated G membranes.

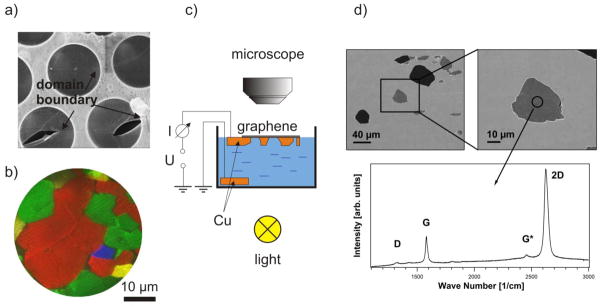

The membranes made of mechanically exfoliated single crystal graphene are inherently clean, have superior mechanical stiffness (1 TPa) [60] and, therefore, are nearly ideal to fabricate electron transparent windows of few micron size. However, the necessity for a high yield dictates the use of CVD grown graphene for membrane fabrication. CVD graphene, grown using standard protocols is a polycrystalline material with single crystalline domains of diameters ranging from sub μm to few μm [64–66] It has been reported that the presence of domain boundaries in the suspended G film,[64] worsen the mechanical strength of suspended graphene by more than on order of magnitude that can also be observed as an increased propensity of graphene tearing along the domain boundaries. Figure 7(a) shows this tendency of membrane rupture along the domain boundaries present in a medium quality graphene after it was transferred onto an orifice array, using a thin poly-methyl-methacrylate (PMMA) protection layer on top of the graphene film. The protection layer was removed after the wet chemical transfer following the recipe described in ref. [62]. This means that for our purposes the size of the single crystalline graphene domains should be appreciably larger than the orifice diameter, which ranges typically between 1 μm and 5 μm. The modified growth protocol reduces the graphene island nucleation rate and thus enlarges the G film domains size [66]. This is illustrated by the low energy electron microscopy (LEEM) image in Fig. 2b, where four rotational domains (colored red, green, blue and yellow) can be identified. The LEEM image clearly shows the existence of single domains larger than 10 μm, so that the achieved graphene quality appears appropriate for the construction of a few micron wide windows covered by boundary free single crystalline graphene. To minimize the graphene contamination, delamination and stress common for standard transfer protocols, we developed a process of controlled back-etching of the Cu supporting foil avoiding the use of any protection layer on top of the grown graphene film. Hence, clean suspended graphene membranes can be obtained that are in intimate contact with the remaining Cu support around the holes. In order to facilitate the process we used Cu foils structured on their backside in predefined areas by photolithography and partial Cu removal in a H2SO4 electrolyte which contained 0.1 M CuSO4. After removal of the photoresist and cleaning the Cu foil the graphene was CVD grown on the front side of the Cu foil. The samples were then placed on the liquid electrolyte in a glass beaker, avoiding any contact of the graphene film with the solution, as sketched in Fig. 7c. By illumination the beaker with light from the bottom, we terminated the electrochemical reaction when the etched holes appeared as bright spots in the backside illuminated microscopy. Since no protection layer was used, some of the suspended membranes collapsed during the electrolyte removal and drying, but many suspended membranes survived, as judged by the different grey level in the SEM images in Fig. 7d. The Raman spectra acquired locally on the suspended holes show the characteristic G-, G*- and 2D- bands and an (almost) absent D-band, which clearly identifies the membranes as a high quality G monolayer [67]. Raman spectroscopy and mapping of such samples is preferable to an SEM imaging, where the electron beam can induce degradation of the graphene. While completely gas tight E-cell still require G membranes of 3 to 5 layers nominal thickness (see section 4), efforts for improving the quality of monolayer thick G membranes for E-cells are continuing [68,69]. Optimizing CVD growth of graphene on Cu [70–72], we are now capable of growing single crystalline graphene domains with diameters larger than 1 mm. Thus, one may even consider covering array of holes with monolayer graphene and sealing supports with multiple compartments or larger area holes that can be used beyond micro-focus applications. The electron transparency of such G membranes has already been tested with SPEM and is reported in the next section 3.3.2.

Fig. 7.

a) SEM (4 keV, In Lens detector) image of moderate quality monolayer graphene on an array of 4.5 μm orifices transferred using poly-methyl-methacrylate (PMMA). After the removal of the PMMA protection layer, graphene exhibits a network of cracks along the domain boundaries. The typical domain size is of the order of a micrometer. b) LEEM image of CVD grown graphene on Cu with improved domain size of up to several 10 μm. c) Scheme of local etching of Cu foil with grown monolayer graphene film. d) SEM images of empty (dark) and suspended (grey) holes in the Cu foil. Weak D-band signal together with a pronounced G and 2D band in the displayed Raman spectrum shows that the produced membrane consists of a high quality monolayer graphene [67].

3.3.2. Photoelectron transparency of GO and G membranes

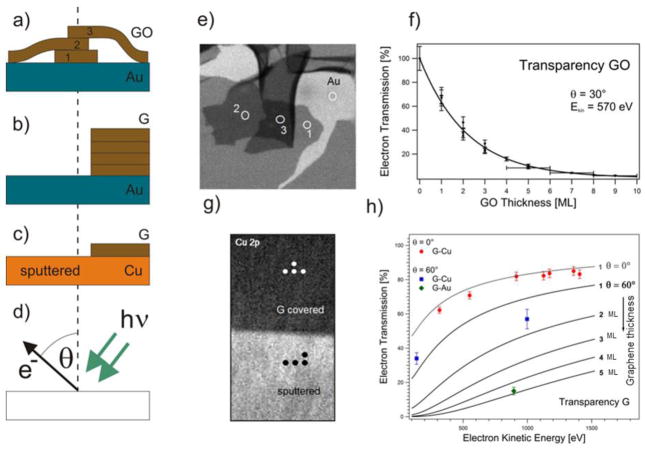

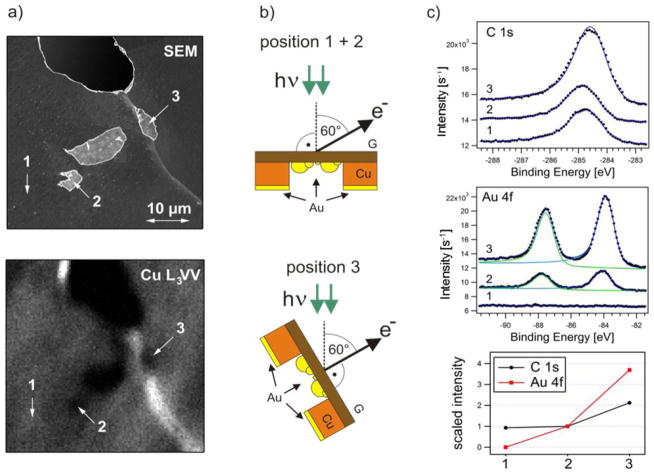

In order to address the transparency of graphene oxide (GO) and graphene (G) membranes, we measured the photoelectron (PE) signal attenuation for membranes transferred to or grown on a supporting substrate. Ultrathin GO films were prepared via dip coating in a Langmuir-Blodgett assembly or drop casting of GO/water colloid solution onto an Au film deposited on a Si wafer (Au/Si wafer) [32]. As sketched in Fig. 8a, the obtained films contain patches of single or multilayer stacked GO platelets, separated by patches of the pristine Au surface.

Fig. 8.

a–c: Different sample arrangements for electron attenuation measurements: (a) drop casted GO, (b) wet-transferred multilayer graphene on Au film, (c) locally Ar+ etched monolayer graphene on Cu. d: Geometry of the PE experiment; e: Au 4f image (64 μm × 64 μm) of GO platelets on Au film; f: Evaluated electron transparency of GO platelets for θ = 30° and Ekin = 570 eV. Dots represent independent measurements where the transmission could be determined with an error of about 10%. GO thicker than 5 layers is determined with accuracy of +/− 1 layer; g: Cu 2p image (320 μm× x 640 μm) of the boundary between the graphene covered and sputter cleaned Cu foil. At the indicated spots local XPS spectra were acquired; h: Extracted electron transparency of graphene at θ = 0° and θ = 60° as a function of kinetic electron energy and layer thickness of the graphene film. The data points were derived from monolayer G-Cu and multilayer G-Au/Si. The solid lines (grey: θ = 0° and black: θ = 60°) show the predicted attenuation curves calculated using TPP-2 formula [74,75,33].

A copper foil was used to obtain monolayer graphene, while G multilayers were grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) on a Ni/SiO2/Si substrate. The multilayer graphene was chemically detached form the metal support and wet transferred onto the Au/Si wafer, using a standard PMMA-based protocol [62]. The transferred G layer covered only a part of the Au support, so there is an abrupt boundary between the G-covered and G-free Au (see Fig. 8b), which could be used for comparative PES analysis. Wet transfer protocols suffer from unavoidable contamination of the membrane material. To compare wet transferred membranes with the ultimately clean ones, we used the graphene layer grown on the Cu substrate removing part of it via 1 keV Ar+ bombardment through a shadow-mask. This procedure resulted in a well-defined boundary between the contaminant-free G layer and a G-free Cu support surface (see Fig. 8c).

The local attenuation of the photoelectron signal, caused by the membrane material, was measured comparing the signal intensity from the G (GO)-covered and G (GO)-free parts of the supports. Using SPEM it was possible to perform spectroscopic measurements in different location selected from the photoelectron images (see Fig 8d). Figure 8e displays the Au image of the Au/Si surface covered by GO platelets of varying thicknesses generated by collecting the emitted Au 4f photoelectrons (PEs), while raster scanning the sample in front of the X-ray microprobe of 650 eV photon energy. The emitted PEs had kinetic energy of ≈ 570 eV and were collected at grazing angle θ = 30°. The grey scale contrast level reflects the Au 4f signal attenuation by the GO platelets on top of the Au film and shows the discrete steps of electron transparency, correlated with the number of the stacked GO platelets. The plot in Fig. 8f clearly demonstrates the expected exponential decay of the electron transparency with the number n of the stacked platelets. This behavior is described by the well-known relationship:

| eq. (1) |

where I/I0 is the ratio between the signal intensity from GO-covered and GO-free surface, which is a measure of the transparency, d is the layer thickness of a GO platelet, n is the number of GO layers and θ is the emission angle of the PEs (see Fig. 8d). λEAL is the effective attenuation length accounting for elastic scattering, which routinely is used instead of the inelastic mean free path λIMFP [73].

Our results have revealed that for the given normal incident photons and grazing acceptance emission geometry and Ekin= 570 eV, the electron transparency of GO scales with the number of layers n as (0.65)n. The same imaging approach was used in the case of the multilayer and monolayer graphene film on Au and Cu, respectively. Here, we illustrate only the results for the case of a Cu support, where the Cu 2p image was acquired using 1070 eV X-ray probe and an acceptance angle of θ = 60° (see Fig. 8g - here micro-spots are indicated, where in addition local Cu 2p (Ekin ≈ 140 eV) and Cu 3p (Ekin ≈ 1000 eV) spectra were acquired). The corresponding electron transparencies versus the photoelectron kinetic energy obtained from this data set are shown as blue squares in the chart of Fig. 8h. The measured transparency of the multilayer G-Au film is also plotted (green diamond). In addition, transparency tests of monolayer G-Cu were performed using conventional Mg Kα and Al Kα radiation of laboratory X-ray source and acquiring electron emission originated from the Cu 2p, Cu 3s and Cu 3p core levels and the Cu L3VV auger transition along the surface normal (θ = 0°). The results of these tests are also plotted in the chart of Fig. 8h (red circles) together with the expected signal attenuation curves for the two acquisition geometries (grey: θ = 0° and black: θ = 60°) for the indicated G-layer thickness as calculated using the so called TPP-2 equation of Tanuma, Powell and Penn [74,75,33]. The theoretical curves are in fair agreement with the experimental points and indicate that for n-layer thick membranes electron transparencies better than (0.5)n are feasible by selecting a proper geometry and photoelectron kinetic energy.

We also tested the electron transparency of higher quality suspended G membranes fabricated via local back etching of Cu foil growth substrate. Such membranes have minimal thickness, ultimate adhesion to the substrate, minimal mechanical stress and do not contain common PMMA-related contaminations. Figure 9a displays a SEM image of representative locally back-etched G/Cu foil sample with one empty and three holes covered with suspended graphene.

Fig. 9.

(a) Left column: SEM (5 kV) and CuL3VV image of the G-Cu foil with empty and suspended holes. The bright diagonal line visible in both images indicates a grain boundary of the Cu foil, where the foil is bent. Three spectra locations 1, 2 and 3 are indicated: as grown graphene on the Cu substrate (1), suspended membrane (2) and suspended membrane (3). (b) Center column: Sketch of the sample after Au evaporation on the membrane backside together with the local geometry of position 1, 2 and 3 in the SPEM. (c) Right column: C 1s and Au 4f spectra acquired from locations 1, 2 and 3 after Au deposition on the sample backside and the corresponding peak intensities scaled to the ones belonging to position 2. Due to the different sample alignment and the grazing geometry of the secondary electron detector used SEM the Cu support appears slightly darker than the G-membranes compared to the SEM images presented in Fig. 7.

The SPEM image of the same area, obtained by collecting CuL3VV Auger electrons, is displayed in the bottom panel of Fig. 9a, where the holes also appear as darker areas. The SPEM images can also contain important topographic information. As described in details in our paper [35], for non-flat samples with topography that varies at microscales, the local orientation of the sampled area with respect to the X-ray microprobe and the electron analyzer can lead to enhancement or attenuation (shadowing) of the photoelectron signal. In fact, the rather uniform brightness of the Cu L3VV image (bottom panel in Fig. 9b) indicates that the Cu foil appears mostly flat, with an exception of the bright diagonal stripe (also present in SEM, see Fig. 9a) where the foil is bent. This stripe is a grain boundary of the Cu foil so the graphene membrane 3 grown over this area is inclined. As sketched in the lower panel in Fig. 9b the inclination angle was found to be ≈ 60° with respect to the X-ray microprobe (for details see the supporting information in ref. [33]). It should be noted that the presence of differently inclined membranes in our sample is an advantage that can be used for exploring the effect of the take-off angle of the photoelectrons on the membrane transparency. The transparency of the membranes was evaluated by depositing thin Au films on their rear side and comparing the C 1s and Au 4f PES spectra of differently inclined membranes (2 and 3 in Fig. 9c). The lower panel in Fig. 9c shows the C 1s and Au 4f spectra measured in locations 1, 2, 3 and normalized to the signal recorded from the membrane 2. Apparently, no Au 4f signal can be registered from the location 1 where Cu was not etched.

One can see that the C 1s intensities from supported (positions 1) and suspended graphene (position 2) are nearly the same, which indicates that both areas, oriented similarly to the X-ray microprobe, contain the same amount of carbon. This confirms that the Cu wet back-etching does not lead to a significant carbonaceous contamination of the back side of the membrane. In position 3, where the membrane is inclined by about 60° with respect to the X-ray microprobe, the C 1s signal is two times stronger, since in this geometry the irradiated area contributing to the C 1s signal is larger by a factor of 1/cos(60°). Comparing the C 1s spectra taken in locations 1, 2 and 3 one can notice that the peak positions are a bit different, which we attribute to some contribution of sp3–like carbon contaminants (introduced by electron irradiation during SEM imaging or during transportation of the samples through air), which lead to a C1s component at higher binding energy [76]. Since the contaminations reduce the membranes electron transparency, pristine or cleaned membranes should have transparency better than the values, derived in the present tests.

A good illustration of geometry effects on the electron transparency measurements is a comparison of the Au 4f spectra from the Au deposited on the back of the membranes 2 and 3. The results in Fig. 9c clearly show that the Au 4f intensity for position 3 is more than three times higher. This is expected, since Au 4f photoemission signal recorded under larger take-off angle contains larger the contribution of the photoelectrons from the bulk Au atoms.

It is important to estimate the detection limit of SPEM experiments through monolayer graphene. For that we first calculated the fraction x of the membrane backside, covered by Au assuming that Au atoms deposited on the backside of the graphene membrane nucleate in to nanoscopic islands as on highly ordered pyrolytic graphite [77]. This was done by comparing the ratio of Cu 3p and Au 4f intensities recorded from Cu support at position 1 (not shown here) and the from location 2 correspondingly. Since both signals are similarly attenuated by the G monolayer on top, these intensities can be related according to equation 2:

| eq. (2) |

Thus, we can determine the fraction x of the backside of G membrane covered by Au islands, using known values for the packing density ρ, the photo ionization cross section σ, the corresponding asymmetry factor β for the angle between photon beam and electron emission angle (60° in this case), the layer distance d and the inelastic mean free path λ and K = [1 − exp(d/λ cos60°)]−1 the bulk photoemission signal contribution for Au and for Cu at the given kinetic electron energy of the acquired photoelectrons. Considering the atom packing of the (100) textured Cu foil [78] with a lattice constant of 3.61 Å and a layer distance d = 1.81 Å and the (111) nature of the Au islands [77] with a lattice constant of 4.08 Å and a layer distance d = 2.36 Å and all other values reported in Table 1, we estimated that about x = 32 % of the membrane’s back surface is covered with Au islands.

Table 1.

Photoionization cross section, asymmetry factor of the core level ionization for the angle of 60° between x-ray beam and electron emission detection in the SPEM and the inelastic mean free path of the Cu 3p and Au 4f photoelectrons at the given kinetic energies. The data were taken from the literature[79] [80].

| Ekin [eV] | λCu in Cu [Å] | λAu in Au [Å] | σ [10−18 cm2] | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Au 4f | 894 | 12.9 | 0.8 | 0.959 | |

| Cu 3p | 903 | 16.3 | 0.08 | 1.582 | |

Using this number, we can now estimate the detection limit of the Au 4f emission through the monolayer G membrane. Conservatively assuming that the detectable Au 4f signal should have an intensity that is 3 times the noise level measured in position 1, we obtain that ≈ 0.4 % of monolayer for gold should be detectable. In the case when the thickness of Au islands is comparable or larger than the photoelectron escape depth, as is our case, the PES sensitivity will be reduced by a factor of KAu = 3.3 so the detection limit becomes ≈ 1 % Au. We want to point out that one can extend the measurement time (the acquisition time of the displayed Au 4f spectrum required less than 3 min) and increase the sensitivity so that using the single layer graphene membrane Au coverage well below 1% of a monolayer can be detected. Although many elements have photo ionization cross sections significantly lower than Au 4f, the presented data clearly show the potential of detecting sub monolayer quantities by membrane based APPES.

4. First AP-SPEM experiments through 2D membranes

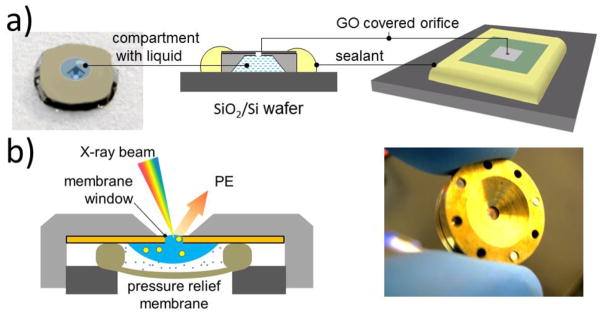

4.1 Membrane-based cells for SPEM studies

We have tested two different cell designs sealed with GO or G-membranes, sketched in Fig. 10. The single use design (Fig. 10a) is based on a Si/SiN chip which has a SiN 50 nm to 100 nm thick window. Using focused ion bombardment (FIB) a micro-orifice was drilled in the center of the SiN window and the hole was covered with a single or a few G or GO layers. The compartment below the SiN membrane can be filled with a liquid and sealed with a UV curable glue on a supporting Si plate for encapsulating the liquid inside.

Fig. 10.

Design of closed graphene/GO E-cell for APXPS studies; a) single orifice disposable cell; b) refillable cell with exchangeable graphene/GO membranes. In addition to SPEM, these cells can also be used in liquid SEM studies. Adapted from refs [32,53].

Figure 10b shows the design of the other type of environmental cell with exchangeable graphene membranes, mounted on a few micron wide orifice, which was laser or FIB drilled in a metal disc or a SiN/Si membrane. A droplet of liquid sample can be placed onto the disk covered with the graphene window. A pressure relief elastomer membrane (Fig. 10b) seals and isolates the sample from the vacuum and also reduces the pressure shocks inside the cell during pumping. One can store ≈ 20 μl of a liquid sample, which lasts from tens of minutes to hours, depending on the leakage rate of the compartment.

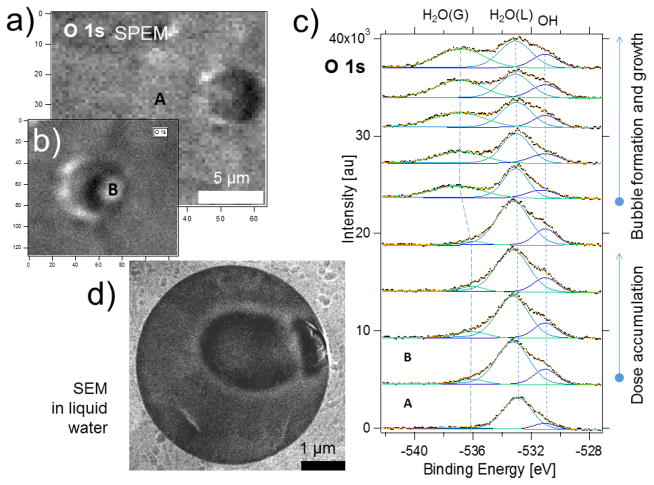

4.2 In situ observation of water radiolysis and bubble formation under high intensity soft X-ray irradiation

To demonstrate the capability of the ambient pressure SPEM through a graphene membrane, we have studied the process of X-ray induced water radiolysis [33], a process widely explored in radiation chemistry and recently in electron microscopy of liquid water [81–84] and frozen hydrated samples [85]. It is known that irradiation of liquid water with X-rays generates ionized and excited molecular and radical species. Some of the long living products of radiolysis, such as (H2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (OH) accumulate [81] and may form micro-bubbles that can be observed with PES if they are located close to the graphene membrane. Figures 11 a and b show the O 1s chemical maps measured through a G membrane sealed 5 μm orifice before and after prolonged irradiation with focused ca 1000 eV X-rays. The panel b illustrates the change of topography at point B inside the membrane window, where the beam was positioned for the spectra acquisition.

Fig. 11.

(a) and (b) O1s maps of the water taken through a graphene covered orifice before (a) and after (b) spectra acquisition at the point B; The characteristic “shadow” on the left side of the feature B (panel b) is a manifestation of the membrane topography change; (c) bottom-up sequential O 1s spectra taken from the location B showing the temporal evolution of liquid (L) and vapor (G) components of water; for the sake of comparison the spectrum A recorded on the graphene covered support outside the membrane is displayed (point A in the left upper panel). e) Liquid SEM images of the electron beam-induced gas bubble formation. Adapted from ref [33].

Figure 11c presents a set of sequentially measured O 1s spectra collected at the point B. For comparison, the bottom spectrum was taken in point A (Fig. 11a), which was few tens of microns away from the membrane. The O 1s spectra were deconvoluted using three components, assigned to OH, H2O (L) and H2O (G), (here L and G stand for liquid and vapor, correspondingly) based on prior research [86][87]. The presence of molecular water and hydroxyl adsorbed species beyond the orifice indicate that some water was trapped under the graphene during the wet transfer procedure or diffused from the orifice [88,23]. The evolution of the sequentially recorded O 1s spectra in the Fig. 11c reveals that the O 1s G component appears and grows at the expense of the L one. This is an evidence of the X-ray beam-induced micro-bubble formation underneath the membrane, which also is concomitant with topographical changes in the O1s map in the Figure 11 b. Similar electron beam induced bubble formation was also observed with SEM, as illustrated in Fig. 11 d, where the lower electron yield from the bubble compared to liquid water accounts for the darker round area in the SEM image. From the practical point of view, although the X-ray induced water radiolysis is an undesired process, since it can obscure other interfacial processes and limits the lifetime of the membrane, the results in Fig. 11 convincingly demonstrate the potential of APPES through graphene membranes to record the spectral information from realistic interfaces with lateral resolution.

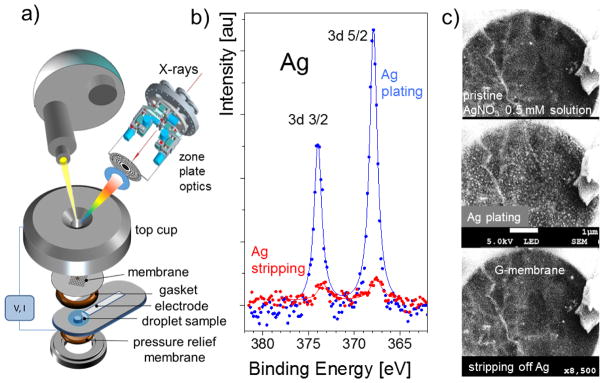

4.3 In situ study of the electrochemical reaction

The current challenges in energy devices such as batteries and fuel cells is to understand the mechanisms of materials degradation, which usually takes place and/or is initiated at the interfaces between working electrolytes and electrodes. Due to its high conductivity and intercalation ability sp2 carbon based materials are often used in these devices. Among the carbonaceous materials graphene, with it’s highest surface to volume ratio, is an ideal model electrode for accessing in-operando the processes occurring at carbonaceous electrodes/liquid electrolyte interfaces.

To test the feasibility of conducting PES electrochemical experiments with liquid electrolytes we designed an electrochemical cell with a graphene window that also acted as a working electrode. A droplet of AgNO3 water solution was placed on the back side of the graphene window, and a silver counter electrode in contact with the droplet was also inserted (see Fig. 12 a). The Ag 3d spectra were recorded from the graphene-covered orifice after applying an appropriate positive or negative potential on the Ag counter-electrode so that the graphene working electrode can play the role of an anode or cathode. The spectra displayed in Fig. 12 b demonstrate the expected growth of the Ag 3d peak intensity, when the graphene acts as an anode and Ag is electrodeposited according to the induced plating reaction. When the potential was reversed, the graphene membrane acts as a cathode so the Ag 3d intensity drops drastically due to the stripping of the Ag deposit. Figure 12 c displays the SEM images of the processes confirming the SPEM results. The SEM image shows how small Ag clusters nucleate and grow on the graphene surface, when the positive potential is applied to the Ag counter electrode and how these Ag clusters dissolve upon the application of the negative potential. These results demonstrate the applicability of soft X-ray APPES for exploring in-situ electrochemical processes in liquid electrolytes.

Fig. 12.

a) Design of an electrochemical cell with an electron transparent graphene window; b) Ag 3d spectra recorded at the graphene membrane/AgNO3 interface at two different potentials between working (graphene) and counter (Ag) electrodes. The top spectrum (blue) corresponds to the plating reaction while the bottom one (red) corresponds to the Ag stripping; c) the concomitant liquid SEM studies of the same reaction in the same setup. The top panel is the initial state of the graphene electrode before applying potential. The middle and bottom panels show the data for applied potentials of +3 V and − 3V, respectively, to the Ag counter-electrode.

5. Outlook

The demands for APPES studies in liquids, solid/liquid, and solid/gaseous interfaces at elevated gas pressures are growing fast, coming from the traditional research fields of catalysis, corrosion and electrochemistry as well as from emerging newer fields such as bio-medical research. The superior versatility of synchrotron (SR) based APPES systems, where also the use of harder X-rays has already been successfully demonstrated [89,16] have already made the synchrotron-based APPES one of the most requested instruments in the large facilities. In fact, hard X-rays allows for experiments with enclosed or microfluidic cells which employ standard (10 to 20) nm thin SiN membranes [30]. Undoubtedly, the limited beamtime available at the large scale facilities requires parallel development of affordable laboratory based APPES instrumentation that can be used for less demanding conditions with the trade-offs in acquisition time and spectral resolution. In this article we review the progress that has been made in APPES with lateral resolution and converting the SPEM into AP-SPEM by using several approaches. Indeed, the SPEM instruments can be operated only at synchrotron facilities, but they provide unique opportunities to explore materials and interfacial processes at their natural length scale. Adding the lateral resolution is the prerogative for understanding the important size-structure-function correlations, required for design and controlled fabrication of smart functional nanomaterials. The overview of the possible approaches for in-operando SPEM experiments, supported by experimental results, clearly suggests that the most promising and versatile approach is based on the use of electron transparent membranes. In this respect, the great advantage of using a sub-microprobe beam in SPEM is that it does not require fabrication of graphene or other electron transparent membranes larger than a few micrometers. Based on the already obtained results with different samples and environments we envision at least three directions where the activities and the developments should be focused in the near future:

1. Radiation induced effects in liquids

The chemical and physical aspects of interaction of high intensity X-ray beams with liquids are still poorly understood, which is important when exploring the behavior of solid functional materials exposed to liquid ambient. This requires extensive investigations of X-ray radiation-induced processes at liquid/solid interfaces exploring surface chemistry in different liquids and their effects on the properties of the immersed objects. In particular, spatial and temporal distributions of the radiation-induced formation of reactive species can be crucial for interpreting the interfacial processes in operating electrochemical and fuel cells, as well as in biological objects.

2. Liquid cells designs

The accumulated knowledge from soft X-ray Microscopy based on X-ray transmission and X-ray photon-in/photon-out spectroscopy[90], and also recently from electron microscopy[91], using Si3N4 windows for a variety of sample set-ups is very helpful for application in hard X-ray APPES, where the IMFP allows for developing environmental cells with Si3N4 windows of thickness of (10 to 20) nm. The cell’s design should follow the current trends, i.e. several optimized designs adaptable to a specific set of experiments exploring, e.g. electrical, micromechanical, thermal, electrochemical and fluidic events. In the case of fluidic cells, since the needed amount of liquids for APPES is rather small, the next generation liquid cells could be disposable monolithic chip with onboard fluidics, where the liquid source together with electrophoretic, electroosmotic or micromechanical pumps are the integral parts of the lab-on-chip technology. Another trend in the e-cells designs could be the incorporation of the additional options for in-situ correlative spectroscopies and microscopies (luminescence, IR, Raman, etc.), using for example the fiber optics.

3. Membranes made of 2D materials

As discussed above, many of the novel 2D materials possess ultimately high electron transparency, high mechanical strength and can be fabricated at large scale. Therefore, these materials will continue to be an object of active research and technical developments as prospective windows for APPES. However, since the purity control and delamination issues of transferred membranes can impede these applications, the future of the 2D membrane windows depends on the advances in wafer scale fabrication and transfer-free protocols, where the support substrate can also be converted to a frame supporting the suspended membranes. The feasibility of fabrication of such single layer graphene windows via local back etching of a Cu substrate has already been demonstrated, as reported above. The outstanding challenge for laboratory based (not microscopic) APPES is the need in large area 2D membranes required in these measurements with a few hundreds microns X-ray beam. The apparent solution that can be used for 2D materials is the fabrication of an array of multiple orifices covered with a 2D membrane. One possible design, depicted in Fig. 13, is a graphene based liquid cell.

Fig. 13.

Prospective design of a microchannel sample platform for laboratory APXPS, where a macroscopic array of liquid filled micro-channels or micro-pores is covered with a graphene membrane. SEM images of a graphene covered micro-channel sample filled with liquid water. The diameter of each channel is 4.5 μm.

The cell is based on a lithographically defined multichannel or microporous matrix, which contains high density of isolated or interconnected microfluidic channels. The channels, a few microns in size, are covered with a graphene membrane. The experimentally demonstrated effective graphene coverage in such multi-hole sample can exceed 95 % (see Fig. 13). This allows for using a standard large beam PES instruments, preserving acceptable vacuum conditions even if parasitic effusion proceeds through a few open channels. Such a multi-channel cell can be equipped with heaters and electrodes, as well as coupled with an on board fluidic management system with sufficient amount of liquid to feed the micro-channels. We note that similar considerations and designs can be applied in an alternative membrane-based APPES, where the membrane protects the entrance of the electron energy analyzer (see Fig. 1).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contributions of A. Yulaev (NIST/UMD), J. Kraus (TUM), I. Vlassiouk (ORNL), M. Amati (Eletttra), M. Abyaneh (now at Diamond SR source), B. Bozzini (U. del Salento) who actively participated in developing and testing the reviewed set-ups. S.G. acknowledge financial support within the framework of the priority program Graphene SPP 1459 of the German Science Foundation (DFG).

References

- 1.Siegbahn K. From X-ray to electron spectroscopy and new trends. Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 1990;51(0):11–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0368-2048(90)80139-2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter B, Faubel M. Photoemission from liquid aqueous solutions. Chemical reviews. 2006;106(4):1176–1211. doi: 10.1021/cr040381p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegbarn H, Asplund L, Kelfve P, Hamrin K, Karlsson L, Siegbahn K. ESCA applied to liquids. II. Valence and core electron spectra of formamide. Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 1974;5(1):1059–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MA, Jordan I, Redondo AB, Kleibert A, Wörner HJ, van Bokhoven JA. In situ photoelectron spectroscopy at the liquid/nanoparticle interface. Surface Science 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starr DE, Wong EK, Worsnop DR, Wilson KR, Bluhm H. A combined droplet train and ambient pressure photoemission spectrometer for the investigation of liquid/vapor interfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2008;10(21):3093–3098. doi: 10.1039/b800717a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegbahn H. Electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis of liquids and solutions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1985;89(6):897–909. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurgensen A, Esser N, Hergenroder R. Near ambient pressure XPS with a conventional X-ray source. Surface and Interface Analysis. 2012;44(8):1100–1103. doi: 10.1002/Sia.4826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao F. Operando Studies of Catalyst Surfaces during Catalysis and under Reaction Conditions: Ambient Pressure X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy with a Flow-Cell Reactor. Chemcatchem. 2012;4(5):583–590. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201200002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy K, Vinod C, Gopinath CS. Design and Performance Aspects of a Custom-Built Ambient Pressure Photoelectron Spectrometer toward Bridging the Pressure Gap: Oxidation of Cu, Ag, and Au Surfaces at 1 mbar O2 Pressure. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2013;117(9):4717–4726. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pantförder J, Pöllmann S, Zhu J, Borgmann D, Denecke R, Steinrück H-P. New setup for in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy from ultrahigh vacuum to 1mbar. Review of scientific instruments. 2005;76(1):014102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson SK, Hahlin M, Kahk JM, Villar-Garcia IJ, Webb MJ, Grennberg H, Yakimova R, Rensmo H, Edström K, Hagfeldt A, Siegbahn H, Edwards MOM, Karlsson PG, Backlund K, Åhlund J, Payne DJ. A versatile photoelectron spectrometer for pressures up to 30 mbar. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2014;85(7):075119. doi: 10.1063/1.4890665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4890665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogletree DF, Bluhm H, Lebedev G, Fadley CS, Hussain Z, Salmeron M. A differentially pumped electrostatic lens system for photoemission studies in the millibar range. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2002;73(11):3872–3877. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bluhm H, Havecker M, Knop-Gericke A, Kiskinova M, Schlogl R, Salmeron M. In situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of gas/solid interfaces at near-ambient conditions 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnadt J, Knudsen J, Andersen JN, Siegbahn H, Pietzsch A, Hennies F, Johansson N, Mårtensson N, Öhrwall G, Bahr S, Mähl S, Schaff O. The new ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy instrument at MAX-lab. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 2012;19(5):701–704. doi: 10.1107/s0909049512032700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmeron M, Schlögl R. Ambient pressure photoelectron spectroscopy: A new tool for surface science and nanotechnology. Surf Sci Rep. 2008;63(4):169–199. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2008.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starr D, Liu Z, Hävecker M, Knop-Gericke A, Bluhm H. Investigation of solid/vapor interfaces using ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Chemical Society Reviews. 2013;42:5833–5857. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60057b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stöhr J. NEXAFS Spectroscopy. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiskinova M. Chemical characterization of surfaces and interfaces with submicron spatial resolution. Surface Interface Analysis. 2000;30:464–471. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Günther S, Kaulich B, Gregoratti L, Kiskinova M. Photoelectron microscopy and applications in surface and materials science. Progress in Surface Science. 2002;70(4–8):187–260. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6816(02)00007-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locatelli A, Bauer E. Recent advances in chemical and magnetic imaging of surfaces and interfaces by XPEEM. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2008;20:093002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barinov A, Dudin P, Gregoratti L, Locatelli A, Mentes TO, Nino MA, Kiskinova M. Synchrotron-based photoelectron microscopy. Nucl Instrum Meth A. 2009;601(1–2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2008.12.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaya S, Ogasawara H, Näslund L-A, Forsell J-O, Sanchez Casalongue H, Miller DJ, Nilsson A. Ambient-pressure photoelectron spectroscopy for heterogeneous catalysis and electrochemistry. Catalysis Today. 2013;205:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballarotto V, Breban M, Siegrist K, Phaneuf R, Williams E. Photoelectron emission microscopy of ultrathin oxide covered devices. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B. 2002;20(6):2514–2518. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang S-H, Mun B, Kay A, Kim S-K, Kortright J, Underwood J, Hussain Z, Fadley C. Depth-resolved photoemission spectroscopy from surface and buried layers with soft X-ray standing waves. Surface science. 2000;461(1):L557–L564. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakita T, Taniuchi T, Ono K, Suzuki M, Kawamura N, Takagaki M, Miyagawa H, Guo F, Nakamura T, Muro T. Hard X-ray photoelectron emission microscopy as tool for studying buried layers. Japanese journal of applied physics. 2006;45(3R):1886. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi K. Hard X-ray photoemission spectroscopy. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 2009;601(1):32–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briggs D, Seah MP. Practical Surface Analysis by Auger and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jablonski A, Powell C. Practical expressions for the mean escape depth, the information depth, and the effective attenuation length in Auger-electron spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films. 2009;27(2):253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smekal W, Werner WS, Powell CJ. Simulation of electron spectra for surface analysis (SESSA): a novel software tool for quantitative Auger-electron spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surface and interface analysis. 2005;37(11):1059–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda T, Yoshikawa H, Noguchi H, Kawasaki T, Kobata M, Kobayashi K, Uosaki K. In situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy for electrochemical reactions in ordinary solvents. Applied Physics Letters. 2013;103(11):111605, 111605–111604. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jennings SG. The mean free path in air. Journal of Aerosol Science. 1988;19(2):159–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-8502(88)90219-4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolmakov A, Dikin DA, Cote LJ, Huang J, Abyaneh MK, Amati M, Gregoratti L, Gunther S, Kiskinova M. Graphene oxide windows for in situ environmental cell photoelectron spectroscopy. Nat Nano. 2011;6(10):651–657. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus J, Reichelt R, Günther S, Gregoratti L, Amati M, Kiskinova M, Yulaev A, Vlassiouk I, Kolmakov A. Photoelectron spectroscopy of wet and gaseous samples through graphene membranes. Nanoscale. 2014;6(23):14394–14403. doi: 10.1039/c4nr03561e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.2015 http://www.elettra.trieste.it/it/lightsources/elettra/elettra-beamlines/esca-microscopy/esca-microscopy.html.

- 35.Günther S, Kolmakov A, Kovac J, Kiskinova M. Artefact formation in scanning photoelectron emission microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 1998;75(1):35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dri C, Africh C, Esch F, Comelli G, Dubay O, Köller L, Kresse G, Dudin P, Kiskinova M. Initial oxidation of the Rh(110) surface: Ordered adsorption and surface oxide structures. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2006;125:9471. doi: 10.1063/1.2345058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gustafson J, Resta A, Mikkelsen A, Westerstrom R, Andersen JN, Lundgren E, Weissenrieder J, Schmidt M, Varga P, Kaspar N, Torrelles X, Ferrer S, Mittendorfer F, Kresse G. Oxygen-induced step bunching and faceting of Rh(553): Experiment and ab initio calculations. Physical Review B. 2006;74:35401. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolia AA, Smiley RJ, Delgass VN, Takoudis CG, Weaver MJ. Surface oxidation of rhodium at ambient pressures as probed by surface-enhanced Raman and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Journal of Catalysis. 1994;150:56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhan RR, Vesselli E, Baraldi A, Lizzit S, Comelli G. The Rh oxide ultrathin film on Rh(100): An X-ray photoelectron diffraction study. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2010;133:214701. doi: 10.1063/1.3509777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amati M, Kazemian Abyaneh M, Gregoratti L. Dynamic High Pressure: a novel approach toward near ambient pressure photoemission spectroscopy and spectromicroscopy. Journal of Instrumentation. 2013;8(05):T05001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blume R, Niehus H, Conrad H, Böttcher A, Aballe L, Gregoratti L, Barinov A, Kiskinova M. Identification of subsurface oxygen species created during oxidation of Ru(0001) Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109:14052. doi: 10.1021/jp044175x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bozzini B, Amati M, Gregoratti L, Mele C, Abyaneh MK, Prasciolu M, Kiskinova M. In-situ photoelectron microspectroscopy during the operation of a single-chamber SOFC. Electrochemistry Communications. 2012;24(0):104–107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2012.09.001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bozzini B, Amati M, Gregoratti L, Kiskinova M. In-situ Photoelectron Microspectroscopy and Imaging of Electrochemical Processes at the Electrodes of a Self-driven. Cell Sci Rep. 2013:3. doi: 10.1038/srep02848. http://www.nature.com/srep/2013/131004/srep02848/abs/srep02848.html#supplementary-information. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Doh WH, Gregoratti L, Amati M, Zafeiratos S, Law YT, Neophytides SG, Orfanidi A, Kiskinova M, Savinova ER. Scanning Photoelectron Microscopy Study of the Pt/Phosphoric-Acid-Imbibed Membrane Interface under Polarization. ChemElectroChem. 2014;1:180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drake IJ, Liu TC, Gilles M, Tyliszczak T, David Kilcoyne A, Shuh DK, Mathies RA, Bell AT. An in situ cell for characterization of solids by soft X-ray absorption. Review of scientific instruments. 2004;75(10):3242–3247. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guay D, Stewart-Ornstein J, Zhang X, Hitchcock AP. In situ spatial and time-resolved studies of electrochemical reactions by scanning transmission X-ray microscopy. Analytical chemistry. 2005;77(11):3479–3487. doi: 10.1021/ac048077j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuchs O, Zharnikov M, Weinhardt L, Blum M, Weigand M, Zubavichus Y, Bär M, Maier F, Denlinger J, Heske C. Isotope and temperature effects in liquid water probed by X-ray absorption and resonant X-ray emission spectroscopy. Physical review letters. 2008;100(2):027801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.027801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tokushima T, Horikawa Y, Harada Y, Takahashi O, Hiraya A, Shin S. Selective observation of the two oxygen atoms at different sites in the carboxyl group (–COOH) of liquid acetic acid. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2009;11(11):1679–1682. doi: 10.1039/b818812b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herranz T, Deng X, Cabot A, Guo J, Salmeron M. Influence of the cobalt particle size in the CO hydrogenation reaction studied by in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113(31):10721–10727. doi: 10.1021/jp901602s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang P, Chen J-L, Borondics F, Glans P-A, West MW, Chang C-L, Salmeron M, Guo J. In situ soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigation of electrochemical corrosion of copper in aqueous NaHCO 3 solution. Electrochemistry Communications. 2010;12(6):820–822. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masuda T, Yoshikawa H, Noguchi H, Kawasaki T, Kobata M, Kobayashi K, Uosaki K. Situ X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy for Electrochemical Reactions at Solid/Liquid Interfaces. Meeting Abstracts; 2014; The Electrochemical Society; pp. 887–887. [Google Scholar]