Abstract

CbpA, the scaffolding protein of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes, possesses one family 3 cellulose binding domain, nine cohesin domains, and four hydrophilic domains (HLDs). Among the three types of domains, the function of the HLDs is still unknown. We proposed previously that the HLDs of CbpA play a role in attaching the cellulosome to the cell surface, since they showed some homology to the surface layer homology domains of EngE. Several recombinant proteins with HLDs (rHLDs) and recombinant EngE (rEngE) were examined to determine their binding to the C. cellulovorans cell wall fraction. Tandemly linked rHLDs showed higher affinity for the cell wall than individual rHLDs showed. EngE was shown to have a higher affinity for cell walls than rHLDs have. C. cellulovorans native cellulosomes were found to have higher affinity for cell walls than rHLDs have. When immunoblot analysis was carried out with the native cellulosome fraction bound to cell wall fragments, the presence of EngE was also confirmed, suggesting that the mechanism anchoring CbpA to the C. cellulovorans cell surface was mediated through EngE and that the HLDs play a secondary role in the attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface. During a study of the role of HLDs on cellulose degradation, the mini-cellulosome complexes with HLDs degraded cellulose more efficiently than complexes without HLDs degraded cellulose. The rHLDs also showed binding affinity for crystalline cellulose and carboxymethyl cellulose. These results suggest that the CbpA HLDs play a major role and a minor role in C. cellulovorans cellulosomes. The primary role increases cellulose degradation activity by binding the cellulosome complex to the cellulose substrate; secondarily, HLDs aid the binding of the CbpA/cellulosome to the C. cellulovorans cell surface.

Clostridium cellulovorans is a mesophilic, anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacterium and utilizes not only cellulose but also xylan, pectin, and several other carbon sources (5, 17, 35). C. cellulovorans produces an extracellular cellulolytic multienzyme complex, which has been called the cellulosome (1, 5), that has a total molecular weight of about 106 and is capable of hydrolyzing crystalline cellulose (5). The cellulosome of C. cellulovorans is comprised of three major subunits, the scaffolding protein CbpA (34), the exoglucanase ExgS (5), and the major endoglucanase subunit EngE (5, 36). One of these subunits, CbpA, is responsible for assembly of the cellulosome and has a molecular weight of 189,000. This nonenzymatic subunit contains a family 3 cellulose binding domain (CBDIII) (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/CAZY/index.html) that binds the cellulosome to cellulose, nine conserved cohesins, and four conserved hydrophilic domains (HLDs). It has been demonstrated that the cohesin domains of CbpA act as receptors for the dockerin domains of the enzymatic components (1, 5).

The organization of C. cellulovorans CbpA is similar to that of the scaffolding proteins from Clostridium acetobutylicum, Clostridium cellulolyticum, Clostridium thermocellum, and Clostridium josui (8, 14, 29, 31). Among the scaffolding proteins from these bacteria, CipA of C. thermocellum contains a divergent dockerin domain (type II) at its C terminus, which interacts with a second class of cohesin domains (type II) present in at least three cell surface proteins (SdbA, OlpB, and ORF2p) (1). This second kind of cohesin-dockerin complex is related to the attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface, whereas the interaction between the type I cohesins and type I dockerins is involved only in cellulosome assembly. Therefore, only the anchoring of the C. thermocellum cellulosome to the cell surface is understood currently. On the other hand, although the roles of CBDIII and cohesin domains of cellulolytic mesophilic clostridia are clear, the function of the HLDs remains unclear (5). Interestingly, it has been shown that the HLDs are found not only in scaffolding proteins but also in several bacterial extracellular glycohydrolases (3, 12, 13). As an example of domains similar to HLDs, fibronectin type III domains (Fn3) are thought to mediate protein-protein interactions and to act as domain linkers in animals (10), and they are found in bacterial extracellular glycohydrolases, including cellobiohydrolase of C. thermocellum (39) and chitinases of Vibrio furnissii (16) and Bacillus circulans (38). Kataeva et al. (15) reported that Fn3 homology domains found in the cellobiohydrolase of C. thermocellum promote hydrolysis of cellulose by modifying its surface, suggesting that these domains might have a functional role rather than being a simple linker between domains. Recently, a three-dimensional structure of the first HLD of the C. cellulolyticum scaffolding protein CipC, designated X2_1, was described in a structural characterization (26). According to the structural studies, the module structure of X2_1 had an immunoglobulin-like fold and exhibited high conformational stability and solubility.

It has been proposed previously that the HLDs in CbpA are involved in anchoring the cellulosome to the cell surface, since these domains have some homology to the surface layer homology (SLH) domains of EngE (36, 37). It has been demonstrated that CbpA can bind EngE through a cohesion-dockerin interaction and that EngE is bound to the cell surface by its SLH domains (5, 18, 36). From these experiments, it was not clear whether the HLDs of CbpA are bound directly to the cell surface. HLDs of CbpA have no homology to Fn3 and SLH domains, which are anchored noncovalently to cell surfaces (25). Therefore, it was important to understand whether the HLDs of CbpA are involved directly in binding the cellulosome to the cell surface and/or play some role during the enzymatic activity of the cellulosome.

In this paper, we describe two functions for the HLDs of CbpA. These domains play a role in promoting cellulose degradation activity due to their binding affinity for cellulose substrates. Furthermore, they play a minor role in binding the cellulosome to the cell surface. This is the first report that describes a function for the HLDs of a mesophilic cellulosomal scaffolding protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and media.

C. cellulovorans ATCC 35296 (35) was used as the source of chromosomal DNA and cell wall preparations. C. cellulovorans was grown anaerobically at 37°C in serum bottles containing a previously described medium (17), which included 5 g of cellobiose per liter. Escherichia coli Novablue and BL21(DE3) (Novagen) or TOP10 (Invitrogen) were used as cloning hosts for production of recombinant proteins and were grown at 18, 30, or 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml; Sigma) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml; Sigma).

Construction of recombinant mini-scaffolding proteins containing HLDs and rEngL.

Ten fragments from CbpA containing 1,518, 921, 1,872, 1,371, 414, 504, 393, 381, 610, and 1,487 bp were amplified by PCR to create expression plasmids pCBP1-22, pCBP2-22, pCBP3-29, pCBP4-29, pCOH9-29, pCBD-22, pHLD1-22, pHLD2-22, pHLD34-29, and pBAD-EngL, respectively. The forward and reverse primers were designed to carry artificial restriction enzyme sites for all genes except the engL gene (Table 1). The amplified fragments were inserted between multiple-cloning sites of pET22b and pET29 (Novagen). The expression plasmids were designed to express fusion proteins with the PelA signal peptide or S-protein tag at the N-terminal end and a six-histidine tag from the vector at the C-terminal end. For construction of pHLD12, which contained HLD1 and HLD2, the splicing overlap extension technique was used (11). For splicing overlap extension, DNA fragments for HLD1 (318 bp) with an additional 5′ sequence at the N terminus (Table 1) and HLD2 (303 bp) were amplified by PCR with a primer set shown in Table 1. The two DNA fragments were combined and fused in the next PCR step with a forward primer for HLD1 (Cbp1-F) and a reverse primer for HLD2 (HLD2-F) containing restriction sites. The band around 620 kbp encoding fusion proteins HLD1 and HLD2 was inserted between the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pET-29b, creating pHLD12SOE. The engL fragment (1.5 kbp) amplified by PCR was cloned directly into the pBAD/Thio expression vector (Invitrogen) by using the TA cloning system according to the manufacturer's instructions, creating the pBAD-EngL expression vector (28). The expressed recombinant EngL (rEngL) did not possess its own signal peptide and was designed to fuse the thioredoxin at its N terminus and a V6 epitope and His tag at its C terminus from the pBAD/Thio vector (Invitrogen). The inserted fragments were sequenced to verify the lack of mutations caused by PCR.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Site | Plasmid(s) | Direction | Positionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cbp1-F | CGAATTCGGCACCAGGTCCAGATGTA | EcoRI | pCBP1-22, pHLD1-29, pHLD12SOE | Forward | 188-193 |

| Cbp1-R | GGGGCTCGAGTGATAATGTTACTGG | XhoI | pCBP1-22, pHLD2-29, pHLD12SOE | Reverse | 686-690 |

| Cbp2-F | CCGAATTCGGGAGAAACGGTAGCAGTA | EcoRI | pCBP2-22 | Forward | 303-308 |

| Cbp2-R | CCGCTCGAGTGTATAACCATTTAATGTCAT | XhoI | pCBP2-22 | Reverse | 600-606 |

| Cbp3-F | CGAATTCGCCAAGTCAACCTGTT | EcoRI | pCBP3-29 | Forward | 945-949 |

| Cbp4-R | GTGCTCGAGTAATGTCATTGTTAT | XhoI | pCBP4-29 | Reverse | 1539-1543 |

| Coh9-F | CGAATTCGGTTAAAATTGACAAAGTATCT | EcoRI | pCOH9-29 | Forward | 1711-1717 |

| Coh9-R | GGGCTCGAGGCTAACTTTAACACTTCCGTT | XhoI | pCOH9-29 | Reverse | 1842-1848 |

| CBD-F | GCGGTTCCATGGCGACATCATCAATG | NcoI | pCBD-22 | Forward | 29-33 |

| CBD-R | CCGCTCGAGTGAAGATGGTACATCTGGACC | XhoI | pCBD-22 | Reverse | 190-196 |

| HLD1-R | GGGGCTCGAGAGCTGCTGGAACTTT | XhoI | pHLD1-29 | Reverse | 314-318 |

| HLD2-F | CGAATTCGAGCGTTACAATAAAT | EcoRI | pHLD2-29 | Forward | 567-571 |

| HLD12SOE-R | TGTAACGCTACCTTCAACTGGTGTGTCAACTACTGT | NSc | pHLD12SOE | Reverse | 282-289 |

| HLD12SOE-F | GGTAGCGTTACAATAAATATTGGAGAT | NS | pHLD12SOE | Forward | 566-574 |

| HLD34-F | CGAATTCGGGAAGGCTAACTATATATTA | EcoRI | pHLD34-29 | Forward | 1507-1512 |

| HLD34-R | CCCCGTCGACAGCAAAATCAGTTACTACTGGATC | SalI | pHLD34-29, pCBP3-29 | Reverse | 1703-1711 |

| ENGL-F | GCACCTAAATTTGACTATTCTGATGC | NS | pBAD-EngL | Forward | 27-35 |

| ENGL-R | ACCAAGAAGTAACTTTTTAAGAAGTGC | NS | pBAD-EngL | Reverse | 514-522 |

Restriction sites and the additional 5′ sequence encoding the N-terminal sequence of the HLD2 linker are indicated by single underlining and double underlining, respectively.

The amino acid positions correspond to positions in CbpA (GenBank accession no. M73817) and EngL (GenBank accession no. AF132735) sequences in the data banks.

NS, additional restriction sites were not designed.

Expression and purification of the recombinant scaffolding proteins.

Ten recombinant proteins were purified from each of the E. coli BL21 strains harboring expression plasmids. When the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were then cultivated at 30°C for 4 h. In the case of rCbp1, rCbp2, rCbp3, rCbp4, and rCoh9, when the E. coli BL21 strain harboring the expression plasmids reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 at 30°C, IPTG was added to a final concentration 0.5 mM, and the cells were cultivated at 18°C for 18 h. After the recombinant E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation, they were resuspended in buffer 1 (50 mM phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole; pH 8.0) and disrupted by sonication. Each of the cell extracts was applied to an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose affinity column (QIAGEN). The recombinant proteins were eluted by using buffer 1 with 250 mM imidazole, and the proteins collected were dialyzed against 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). To eliminate the S-protein tag sequence at the N terminus of rCbp3, rCbp4, rHLD1, rHLD2, rHLD12, rHLD34, and rCoh9, the proteins were treated with an S-tag thrombin purification kit (Novagen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Each of dialyzed protein preparations was concentrated to 1.0 to 1.8 mg/ml by ultrafiltration (Ultra free biomax −10; Millipore).

Construction and expression of rEngE and rEngL.

rEngE was expressed by using E. coli BL21 harboring expression plasmid pENGE, as described previously (18). In the case of rEngL, when the E. coli Top10 strain harboring pBAD-EngL, which was constructed as described previously (28), reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 at 30°C, l-arabinose (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.5% (wt/vol), and the cells were cultivated at 15°C for 18 h. The rEngL was purified by the same procedures by using Ni-N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine affinity column chromatography as described above. Purified rEngE and rEngL were also concentrated to 1.2 to 1.8 mg/ml by ultrafiltration (Ultra free biomax −30; Millipore).

Fractionation and preparation of C. cellulovorans cell wall fragments.

C. cellulovorans cell wall fractions were isolated as described previously (18). C. cellulovorans cells from 500 ml of an early-stationary-phase culture were harvested by centrifugation at 12,100 × g for 10 min. The culture supernatant and an aliquot of the cell suspension were designated the supernatant and the whole-cell fraction, respectively. The cell suspension was disrupted by sonication. The resulting supernatant was designated the cell extract fraction, and the pellet, which was suspended in 5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), contained the crude cell wall fraction. The crude cell wall fraction was treated with 1% Triton X-100 at 30°C for 2 h with gentle shaking and centrifuged at 39,200 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was designated the cell membrane fraction. The pellet from the cell membrane fraction was also treated with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) by heating it at 100°C and centrifuged at 39,200 × g for 20 min at room temperature. The supernatant consisted of the cell wall-associated proteins. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) after three washes with the phosphate buffer. This suspension consisted of cell wall fragments containing peptidoglycan. In order to remove covalently bound cell wall polymers from the peptidoglycan layer, the method of Ries et al. (32) was used for extraction as described previously (18). After treatment of the cell wall fraction, the pellet was washed three times with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and resuspended in the same buffer.

Preparation of native cellulosomes from a C. cellulovorans cellobiose-grown culture.

C. cellulovorans cellulosomes were prepared from 500 ml of a cellobiose-grown culture as described previously (17). Native cellulosomes were concentrated to 10 to 20 mg/ml by ultrafiltration (Ultra free biomax −100; Millipore).

Interaction of each recombinant protein with cell wall fragments of C. cellulovorans.

Binding experiments were carried out by incubating and cosedimenting each of the recombinant proteins with cell wall fragments as described previously (18). Each polypeptide (20 to 50 μg) or native cellulosomes (40 to 50 μg) prepared from a C. cellulovorans culture were mixed with 20 μl of cell wall fragments (75.1 μM diaminopimelate), and the reaction volume was brought to 50 μl with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 4 h at 30°C with gentle shaking. The bound and free polypeptides were separated by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min at room temperature. The supernatant consisted of the soluble fraction. A wash fraction was obtained after the cell walls were washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The pellets, consisting of the insoluble cell wall fragments and attached proteins, were washed with the same buffer and then resuspended with 50 μl of the phosphate buffer. Each fraction was loaded onto SDS-10 or 12% polyacrylamide gels.

The concentrations of polypeptides in the total pellet suspension and free polypeptides in the pooled supernatants were determined by using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). The amount of bound polypeptides was calculated by subtracting the amount of free polypeptides remaining in the pellet suspension. The binding affinity (Kd) and binding capacity parameters were calculated by using double-reciprocal plots with different fixed levels of bound proteins and meso-diaminopimelate as described previously (18).

Preparation of specific antisera for C. cellulovorans CbpA and EngE.

An immunoblot analysis was performed by using polyclonal antiserum against purified rHLD1, rHLD34, and rEngE (18). The purified recombinant polypeptide (200 μg) was mixed with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant and injected subcutaneously into a New Zealand White rabbit. The second injection was administered after 2 weeks by using the same amount of the protein with the adjuvant. The antisera (anti-HLD1 and anti-HDL34) were collected 2 weeks after the second injection.

Analysis of the peptidoglycan of C. cellulovorans.

In order to determine the amino acids and the diaminopimelate content in peptidoglycan, cell wall fragments were analyzed with a Beckman 6300 amino acid analyzer as described previously (18).

Assembly of recombinant cellulosomes.

Two nanomoles of the purified recombinant scaffolding proteins (rCbp1, rCbp2, rCbp3, and rCbp4) and 10 nmol of rEngL as the cellulosomal subunit were mixed in 100 μl of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) containing 5 mM CaCl2 and kept for 15 h at 4°C. The assembly of scaffolding proteins and cellulolytic subunits was confirmed by comparison of the mobility to the mobility of noncomplexed forms by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) by using 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gels as described previously (27).

Affinity of each recombinant protein for insoluble and soluble polysaccharides.

Various amounts of each recombinant polypeptide (20 to 100 μg) were incubated for 4 h at 30°C with gentle shaking in 200 μl of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing Avicel (Sigma) and chitin (Sigma) at a concentration of 20 mg/ml as an insoluble polysaccharide or with carboxylmethyl cellulose (CMC) (medium viscosity; Sigma) at a concentration of 50 mg/ml as a soluble polysaccharide. Free polypeptides were separated from bound polypeptides by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min at room temperature, except for CMC. Each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In the case of binding for CMC, aliquots of the reaction mixtures were applied immediately to a native PAGE gel. To calculate the binding parameter for insoluble carbohydrates, the concentrations of the polypeptide in the total pellet suspension and free polypeptide were determined in the pooled supernatants by using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). The amount of bound polypeptide was calculated by subtracting the amount of free polypeptide remaining in the pellet suspension. The affinity (Kd) and binding capacity parameters were calculated by using double-reciprocal plots with different fixed levels of bound proteins and insoluble materials as described previously (18).

Determination of cellulase activities.

The cellulase activities were measured in the presence of substrates at a concentration of 0.2% (wt/vol) at 37°C for 15 h in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 5 mM CaCl2. The phosphate concentration in the reaction mixture was not influenced for hydrolysis activities of EngL. The reducing sugar released as d-glucose was measured by the Somogyi-Nelson method (27). The substrates used were Avicel, acid-swollen cellulose, and CMC. Cellulase activity was expressed in micrograms of released reducing sugar per milliliter of reaction mixture.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

SDS-PAGE and native PAGE were performed with ready-made 10 or 12% and 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad), respectively (19, 27). The immunoblot analysis was performed by using anti-HLD1, anti-rHLD34, and anti-EngE (18) antisera. The procedure was performed as described previously (18, 36).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparation of nine recombinant scaffolding proteins and rEngL.

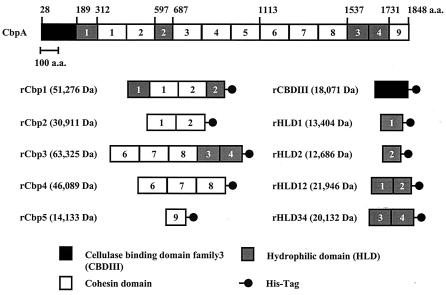

To investigate the functions of the HLDs in the C. cellulovorans scaffolding protein CbpA, several recombinant scaffolding proteins with or without HLDs were constructed and expressed by E. coli (Fig. 1). In addition, rEngL was constructed to serve as an enzymatic cellulosomal subunit. Among the recombinant scaffolding proteins, rCbp1 and rCbp3 were composed of two HLDs and of two and three cohesin domains, respectively. In contrast, rCbp2 and rCbp4 consisted of only two and three cohesin domains, respectively. These recombinant scaffolding proteins with and without HLDs were expressed successfully to the E. coli periplasmic space as soluble proteins and were purified almost to homogeneity by Ni affinity chromatography. EngL, which consists of a glycosyl hydrolase family 9 catalytic domain and a dockerin domain, was selected as a representative cellulosomal enzyme subunit. To express EngL as a soluble protein, EngL was expressed as a fused protein with thioredoxin by using the pBAD/Thio vector (27, 28). The apparent molecular mass of the each purified protein as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis was in good agreement with the theoretical molecular weight (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of recombinant scaffolding proteins used in this study. The 10 scaffolding proteins were expressed by the pET system in E. coli BL21. Plasmid construction is described in Materials and Methods. The numbers in the CbpA protein show the order of the HLD and cohesin domains from the N terminus. a.a., amino acids.

Sequence analysis of HLDs in C. cellulovorans CbpA.

Preliminary analyses of the HLDs present in CbpA were carried out to determine the homology among the four HLDs and among the HLDs and sequences found in other microorganisms. Homology studies of HLD1 (180 to 312 amino acids of CbpA), HLD2 (597 to 787 amino acids), and HLD34 (1,537 to 1,731 amino acids) with BLAST revealed high levels of similarity and identity among HLD1, HLD2, and HLD34 (46 to 57% identity and 58 to 64% similarity). In addition, the HLDs of C. cellulovorans CbpA had high homology to HLDs of C. acetobutylicum CipA (accession no. CAC0910) (36 to 44% identity and 48 to 63% similarity), C. cellulolyticum CipC (accession no. AAC28899) (36 to 43% identity and 48 to 59% similarity), and C. josui CipA (accession no. T30433) (28 to 30% identity and 36 to 40% similarity). The HLDs of C. cellulovorans CbpA were also homologous to the unknown domain in endo-β-1,4-glucanase EG-Z (Avicelase I) (accession no. P23659) (39 to 45% identity and 54 to 61% similarity) and exo-β-1,4-glucanase (Avicelase II) (accession no. P50900) (39 to 45% identity and 54 to 61% similarity) of Clostridium stercorarium and endo-β-1,4-glucanase (accession no. P23550) (30 to 36% identity and 44 to 53% similarity) of Bacillus lautus strain PL236. The levels of similarity and homology between the domains of scaffolding proteins and glycosidases suggested that these domains probably arose by gene duplication from the same ancestor.

On the other hand, when the HLDs of C. cellulovorans CbpA were compared with the SLH domains of EngE (accession no. AAD39739), only slight homology at the amino acid level was observed (13 to 16% identity and 19 to 21% similarity). Therefore, the results of sequence alignment studies suggested that the HLDs of CbpA may have a function different than that of the SLH domains of EngE, which anchor the cellulosome to the cell surface.

Binding of the HLDs to C. cellulovorans cell wall fragments.

It was proposed previously that HLDs might anchor CbpA to the C. cellulovorans cell surface (5, 36). To study this potential role for the HLDs, we performed binding tests for the cell surface with several recombinant proteins, including rEngE. rEngE bound to CbpA by a cohesin-dockerin interaction and bound to the cell surface through its SLH domains when cell wall fragments were prepared from cells grown on cellobiose (36).

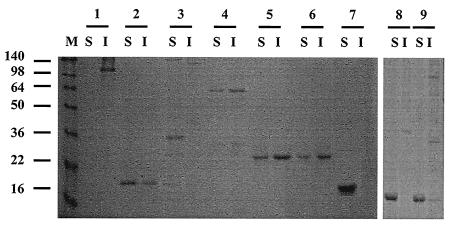

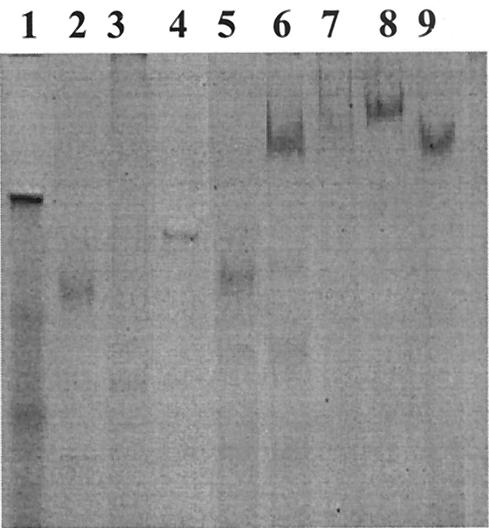

Eight recombinant proteins (rEngE, rCBDIII, rCbp1, rCbp2, rHLD1, rHLD2, rHLD12, and rHLD34) were tested for binding to the cell wall fraction. The rCbp1, rHLD1, rHLD2, rHLD12, and rHLD34 proteins were designed to possess HLDs; however, rCbp2 and rCBDIII consisted of only cohesin and the CBD, respectively (Fig. 1). One of these recombinant proteins, rEngE, showed strong binding to the cell wall fraction (Fig. 2, lane 1I). On the other hand, rCBDIII, rCbp1, rHLD12, and rHLD34 were found not only in the soluble fraction but also in the insoluble fraction, indicating that they were bound to the cell wall fraction (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 5, and 6). The rCBDIII protein could bind to the cell wall, suggesting that the CBD may have affinity for cell wall polymers, such as N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid, which are components of the peptidoglycan layer (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Interaction of rHLDs and EngE with the cell wall fraction of C. cellulovorans. Purified rHLDs and rEngE were incubated with the cell wall fraction. The insoluble material was precipitated and washed as described in Materials and Methods. The presence of the protein in an insoluble fraction lane indicates binding of the protein to the cell wall fraction. Each sample was treated by boiling for 5 min in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol, and SDS-PAGE was carried out under denaturing conditions. Lanes 1, EngE; lanes 2, rCBDIII; lanes 3, rCbp2; lanes 4, rCbp1; lanes 5, rHLD12; lanes 6, rHLD34; lanes 7, rCoh9; lanes 8, rHLD1; lanes 9, rHLD2; lanes S, soluble fraction; lanes I, insoluble fraction. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) (lane M) are indicated on the left.

To compare the binding affinities and capacities of rHLDs and rEngE for the C. cellulovorans cell wall fraction, we measured their binding parameters (Table 2). The rEngE protein showed the highest affinity and binding capacity values (Kd, 1.3 μM; binding capacity, 165 μmol/g) among the recombinant proteins. In contrast, the Kd values for rHLD1, rHLD2, rHLD12, and rHLD34 were 28.2, 20.5, 10.5, and 7.2 μM, respectively, and the binding capacity values were 37, 32, 70, and 82 μmol/g, respectively. These Kd values are 9 to 30 times lower than the Kd value for rEngE, and these binding capacity values are two to five times lower than the binding capacity value for rEngE (Table 2). Although the values for the binding parameters of individual HLDs were low, in tandem HLDs such as rHLD12 and rHLD34 had about twofold-greater binding ability. These results indicated that the number of HLDs in CbpA may be important for increasing the binding affinity of CbpA for the C. cellulovorans cell surface. The CbpA protein of C. cellulovorans and CipA of C. acetobutylicum contain four and six HLDs, respectively. Therefore, CbpA and CipA may have higher affinities for the cell surface than scaffoldins that have fewer HLDs.

TABLE 2.

Parameters for binding HLDs to C. cellulovorans cell wall fragmentsa

| Recombinant protein | Cell wall binding

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | Capacity (μmol/mol)b | |

| rCoh9 | NDc | ND |

| rEngE | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 165 |

| rHLD1 | 28.2 ± 3 | 22 |

| rHLD2 | 20.5 ± 2 | 27 |

| rHLD12 | 10.5 ± 5 | 70 |

| rHLD34 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 82 |

The data are averages for three determinations.

Binding capacity of cell walls, expressed as micromoles of bound recombinant protein per mole of meso-diaminopimelate.

ND, not detected or negligible amount.

Localization of CbpA on the C. cellulovorans cell surface.

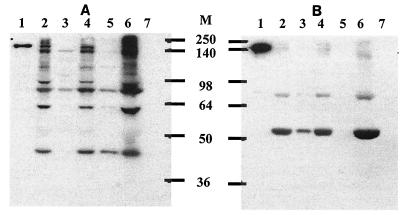

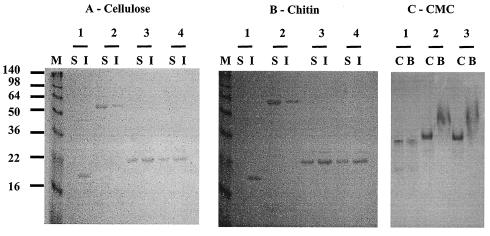

To confirm that CbpA is localized on the C. cellulovorans cell surface, we carried out immunoblot analyses with two antisera (anti-HLD1 and anti-HLD34). When an immunoblot analysis was performed for each C. cellulovorans cell fraction with anti-HLD1, many signals were detected between 40 and 189 kDa in all fractions except the cell extract fraction and cell wall fragment fraction (Fig. 3A). In addition, when anti-HLD34 was used to test each fraction in immunoblot analyses, a major signal (around 55 kDa) which did not correspond to the predicted CbpA molecular mass (189 kDa) was detected (Fig. 3B, lane 1). When the two signals were compared, it was found that the signals for the 55-kDa band obtained with anti-rHLD34 were much stronger than those obtained with anti-rHLD1. Therefore, it appears that the affinity of HLD34 for the cell wall fraction is stronger than that of HLD1 or HLD2, since HLD34 consists of two individual HLDs. These results were reflected in the Kd and binding capacity values when the binding affinities of rHLD12 and rHLD34 were compared with those of individual HLDs (Table 2). On the other hand, the difference between the immunoblot analysis results when the two antisera were used appeared to be due to fragmentation of CbpA during the preparation of the cell wall fragments and the specificity of the antiserum.

FIG. 3.

Localization of CbpA on C. cellulovorans cells. Immunoblot analysis was carried out with anti-HLD1 (A) and anti-HLD34 (B) antisera by using each cell fraction as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, supernatant of C. cellulovorans cellobiose-grown culture; lane 2, whole cells; lane 3, cell extract; lane 4, crude cell walls; lane 5, crude cell walls after extraction with Triton X-100; lane 6, cell wall proteins; lane 7, SDS-extracted cell wall fragments. The positions of molecular mass markers (M) (in kilodaltons) are indicated between the panels. Four and ten microliters of each fraction were used for immunoblot analysis.

It is known that the protuberance layer surrounds the surface layer of C. thermocellum (1) and C. cellulovorans (2). In addition, it has been suggested that the cellulosomes of both bacteria generally coat the exterior surface of the resting protuberance (1, 2). Therefore, the results of these immunoblot analyses supported the localization of C. cellulovorans cellulosomes on the cell surface (Fig. 3).

It is known that hydrofluoric acid (HF) treatment of cell wall fragments removes secondary polymers, such as N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylmannosamine, and N-acetylmuramic acid, and diaminopimelate by cleavage of phosphodiester linkages from the peptidoglycan layer (32). We observed that not only native C. cellulovorans cellulosomes but also EngE lost the ability to bind to the cell wall fraction after HF treatment. It was reported previously that EngE lost the ability to bind to C. cellulovorans cell wall fragments when it was treated with HF (18). However, the binding affinity and binding pattern of rHLD12 and rHLD34 for cell wall fragments were not influenced by treatment with HF (data not shown). Therefore, these results suggested that there might be a difference between the cell wall binding mechanisms of EngE and HLDs.

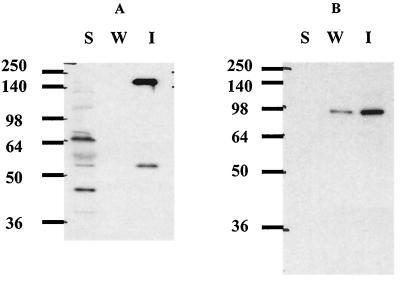

To consider the anchoring mechanism of CbpA, we carried out cell wall binding tests using native cellulosomal fractions from cellobiose-grown cultures. When the native cellulosomes were tested for the ability to bind to cell wall fragments, the presence of CbpA with the cell wall fragments was observed by immunoblot analyses when anti-HLD34 antiserum was used (Fig. 4A). When anti-EngE antiserum was used for the binding test with native cellulosomes, EngE was also located in the native cellulosome fraction bound to the cell wall fragments (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that EngE functioned mainly as an anchoring protein for CbpA through its cohesin-dockerin interaction and through its SLH domains. As the HLDs of CbpA have an affinity for cell wall polymers, the HLDs may play a supplementary role in the attachment of CbpA to the C. cellulovorans cell surface with EngE. This anchoring role of C. cellulovorans CbpA is slightly different from the anchoring mechanism of CipA of C. thermocellum, which binds to the cell surface layer through the anchoring proteins SbdA, OlpB, and ORF2p (7, 20, 21, 22, 23, 33).

FIG. 4.

Interaction between native cellulosomes and the C. cellulovorans cell wall fraction. The cellulosomal fraction prepared from a C. cellulovorans cellobiose-grown culture was incubated with the cell wall fraction. The insoluble material was precipitated and washed as described in Materials and Methods. The materials were loaded on 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gels and blotted onto membranes. (A) Binding of C. cellulovorans native cellulosome to the cell wall fraction as determined by immunoblotting with anti-HLD34 antiserum. (B) Localization of EngE in C. cellulovorans cellulosomes bound to the cell wall fraction as determined by immunoblotting with anti-EngE antiserum. Lane S, soluble fraction; lane W, wash fraction; lane I, insoluble fraction. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Effects of the presence of HLDs in the cellulosome on cellulose degradation activities.

To investigate whether the HLDs of CbpA influence the enzymatic activity of the cellulosome complex, recombinant cellulosomes were assembled in vitro. Each purified scaffolding protein and rEngL were mixed at a molar ratio of one scaffolding protein molecule to five rEngL molecules in sodium phosphate buffer with CaCl2. The calcium ion is necessary for binding between cohesins and dockerins (5, 30). The assembly of each scaffolding protein and rEngL was confirmed by native PAGE analysis (Fig. 5). These results indicated that assembly of rCbp1, rCbp2, rCbp3, rCbp4, and rEngL occurred successfully.

FIG. 5.

Assembly of mini-cellulosomes with rEngL: native PAGE of mini-cellulosomes assembled with four recombinant mini-scaffolding proteins and rEngL. Lane 1, rEngL; lane 2, rCbp1; lane 3, rCbp2; lane 4, rCbp3; lane 5, rCbp4; lane 6, rCbp1 plus rEngL; lane 7, rCbp2 plus rEngL; lane 8, rCbp3 plus rEngL; lane 9, rCbp4 plus rEngL.

When rEngL was incubated with Avicel, acid-swollen cellulose, and CMC, we observed high glycosyl hydrolase activity with all of the substrates (Table 3). On the other hand, the scaffolding proteins, rCbp1, rCbp2, rCbp3, and rCbp4, did not show degradation activity with any of the substrates. When scaffolding proteins containing HLDs (rCbp1 or rCbp3) and rEngL were incubated with the three substrates, the hydrolysis activity was facilitated compared with that of the complexes without HLDs (Table 3). Especially when the cellulosomal complex consisting of rCbp3 and rEngL was used with CMC, the amounts of released sugar indicated not only maximum activity but also the greatest synergistic effects (Table 3). It has been reported previously that recombinant mini-cellulosomes consisting of the subunits and scaffolding proteins containing CBDIII lead to synergistic effects for cellulose degradation activity in C. thermocellum (4), C. cellulolyticum (6), and C. cellulovorans (27) compared with the activity of the enzyme alone or the enzyme without CBDIII. These reports suggested that binding of cellulosomes to substrates was important for increasing the synergistic effects of the glycosyl hydrolysis activity of cellulosomes. In a similar report, the Fn3-like domain of C. thermocellum CbhA not only bound to cellulose but also promoted glycosyl hydrolysis activity by modifying the cellulose surface (15). Therefore, these results indicated that HLDs also might contribute to the glycosyl hydrolase activity of the C. cellulovorans cellulosome by their affinity to substrates.

TABLE 3.

Effects of combinations of EngL and several mini-scaffolding proteins with or without HLDs on hydrolysis activity of cellulose substrates

| Recombinant protein(s) | Amt of released sugars (μg/ml) witha:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Avicel | Acid-swollen cellulose | CMC | |

| rEngL | 32.2 ± 0.2 (1.0)b | 125.7 ± 1.2 (1.0) | 498.7 ± 1.2 (1.0) |

| rCbp1 | NDc | ND | ND |

| rCbp1 and rEngL | 52.4 ± 0.1 (1.6) | 163.4 ± 1.0 (1.3) | 699.1 ± 2.0 (1.4) |

| rCbp2 | ND | ND | ND |

| rCbp2 and rEngL | 40.7 ± 0.1 (1.3) | 130.7 ± 1.2 (1.0) | 518.0 ± 2.2 (1.0) |

| rCbp3 | ND | ND | ND |

| rCbp3 and rEngL | 55.5 ± 0.5 (1.7) | 201.3 ± 1.0 (1.6) | 899.7 ± 2.8 (1.8) |

| rCbp4 | ND | ND | ND |

| rCbp4 and rEngL | 39.1 ± 0.2 (1.2) | 139.2 ± 3.0 (1.1) | 548.9 ± 3.0 (1.1) |

Hydrolysis activity is expressed as the amount of reducing sugar released per milliliter of reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was composed of 0.5% (wt/vol) substrate, 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 5 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.0), and each recombinant protein at a concentration of 0.5 to 1 μM. The reaction was performed with gentle shaking at 37°C for 15 h.

Synergy (in parentheses) was calculated by dividing the activity with the scaffolding protein by the activity without the scaffolding protein. The synergism coefficient indicates the ratio of measured activity to theoretical activity.

ND, not detected.

Binding affinity of HLDs for several polysaccharides.

In addition to the reports described above, the search for conserved domains of the HLDs in the CDD database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) (24) suggested that the function of these domains may involve interaction with carbohydrates (pfam03442.10,DUF291). The HLDs together with CBDIII in CbpA might help cellulosomes adhere to cellulose and other polysaccharides. Thus, to confirm whether HLDs could also interact with insoluble polysaccharides (cellulose and chitin) or soluble cellulose (CMC), we examined whether rCbp2, rCBDIII, rHLD12, and rHLD34 could bind to cellulose, chitin, and CMC. When rCbp2 was incubated with cellulose, chitin, and CMC, no significant binding was observed with these substrates, suggesting that the cohesin domains of CbpA were not involved in polysaccharide binding (data not shown). In contrast, when rCBDIII (Fig. 6, lane 1), rHLD12 (Fig. 6, lane 3), and rHLD34 (Fig. 6, lane 4) were mixed with cellulose, chitin, and CMC, the recombinant proteins were able to bind these substrates. To compare the binding parameters of rHLD12 and rHLD34, binding affinity (Kd) and binding capacity were measured for cellulose and chitin. In the case of rCBDIII, the Kd and binding capacity values showed high levels of binding for both substrates (Kd and binding capacity for Avicel, 0.4 μM and 3.4 μmol/g, respectively; Kd and binding capacity for chitin, 1.5 μM and 2.1 μmol/g, respectively). The binding parameters of rCBDIII for both substrates were in good agreement with those reported previously (9).

FIG. 6.

Binding of HLDs and CBDIII to cellulose, chitin, and CMC. Purified recombinant proteins were incubated with cellulose and chitin. After centrifugation, proteins in the supernatant (lanes S) and in the precipitate (lanes I) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (A) Binding to cellulose. Lanes 1, CBDIII; lanes 2, rCbp1; lanes 3, rHLD12; lanes 4, rHLD34. (B) Binding to chitin. Lanes 1, CBDIII; lanes 2, rCbp1; lanes 3, rHLD12; lanes 4, rHLD34. (C) Binding to CMC. Lanes 1, rCbp2; lanes 2, rHLD12; lanes 3, rHLD34. Binding was analyzed by native PAGE. Lanes C without polysaccharide served as a reference. Lanes B contained polysaccharide. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) (lane M) are indicated on the left.

Although rCbp2 did not bind cellulose and chitin, rHLD12 (Kd and binding capacity for Avicel, 1.0 μM and 1.9 μmol/g, respectively; Kd and binding capacity for chitin, 3.0 μM and 0.93 μmol/g, respectively) and rHLD34 (Kd and binding capacity for Avicel, 1.2 μM and 1.4 μmol/g, respectively; Kd and binding capacity for chitin, 2.2 μM and 1.83 μmol/g, respectively) could bind both substrates (Table 4). Therefore, the results showed that rHLD12 and rHLD34 had affinity for cellulose substrates and might be able to perform like CBDIII. Interestingly, there were no remarkable differences for binding parameters between rHLD12 and rHLD34 for both substrates. These results may reflect the sequence similarity among HLD1, HLD2, and HLD34, suggesting that each domain might have the same ability to bind cellulose substrates.

TABLE 4.

Parameters for binding of recombinant scaffolding proteins to Avicel and chitina

| Recombinant protein | Avicel

|

Chitin

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | Binding capacity (μmol/g)b | Kd (μM) | Binding capacity (μmol/g) | |

| rCBDIII | 0.4 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| rCbp2 | NDc | <0.01 | ND | <0.02 |

| rHLD12 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.93 |

| rHLD34 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.89 |

The data are means for three determinations.

Maximum amount of protein bound to 1 g of Avicel or chitin.

ND, not detected.

Although the effects of HLDs were very similar to those of the CBDIII and Fn3-like domains, there was no amino acid sequence homology between these domains except for a short R-X1-X2-X3-VDG motif of the CBDIII and Fn3-like domains (15). This short motif was considered important for formation of calcium binding centers. In fact, the CBDIII and the Fn3-like domains contained 1 and 2 mol of calcium per mol, respectively. On the other hand, parameters for HLD binding to cellulose substrates were not altered by the presence of chelating agents, such as EDTA. In addition, both CBDIII and Fn3-like domains were found to lead to morphological changes on cellulose surfaces; however, electron microscopy analysis of cellulose treated with HLDs did not reveal any changes on the cellulose surface (data not shown). Therefore, while HLDs may have a function similar to that of Fn3 and CBDIII in vivo, the mechanism of binding to polysaccharides might be different. It is not known how HLDs bind to the cellulose substrate.

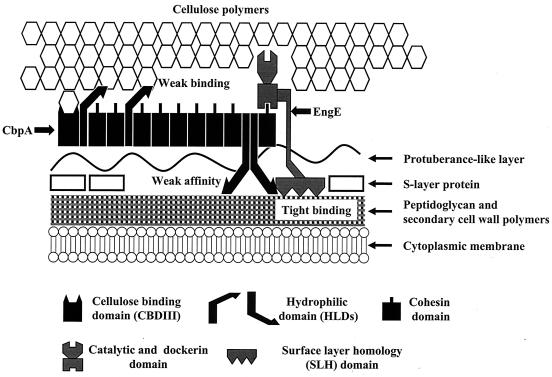

Figure 7 shows a model of the functions of the HLDs of the C. cellulovorans scaffolding protein CbpA. We propose that the HLDs of CbpA have two roles: (i) HLDs facilitate the attachment of CbpA to the cell surface and assist the anchoring function of the SLH domains of EngE and (ii) HLDs in conjunction with CBDIII increase the glycosyl hydrolytic activity of C. cellulovorans through effective binding of the cellulosome to the cellulose substrate.

FIG. 7.

Model showing attachment of CbpA to the cell surface of C. cellulovorans mediated by EngE and HLDs. The HLDs of CbpA can help not only to attach a CbpA/cellulosome to the cell surface but also to bind the cellulosome to the cellulose substrate. The binding affinities of the HLDs for the substrate and the cell surface are not strong. The three repeated SLH domains of the N terminus of EngE integrate into the cell wall layer containing peptidoglycan, while the C-terminal dockerin of EngE is bound to CbpA. We propose that EngE plays a major role in attaching CbpA to the cell surface and that the HLDs of CbpA play a subordinate role in this attachment process.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Helen Chan for skillful technical assistance.

This research was supported in part by grant DE-DDF03-92ER20069 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer, E. A., L. J. W. Shimon, Y. Shoham, and R. Lamed. 1998. Cellulosome-structure and ultrastructure. J. Struct. Biol. 124:221-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair, B. G., and K. L. Anderson. 1999. Regulation of cellulose-inducible structures of Clostridium cellulovorans. Can. J. Microbiol. 45:242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronnenmeier, K., K. P. Rucknagel, and W. L. Staudenbauer. 1991. Purification and properties of a novel type of exo-1,4-beta-glucanase (avicelase II) from the cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium stercorarium. Eur. J. Biochem. 200:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrard, G., A. Koivula, H. Soderlund, and P. Beguin. 2000. Cellulose-binding domains promote hydrolysis of different sites on crystalline cellulose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10342-10347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi, R. H., A. Kosugi, K. Murashima, Y. Tamaru, and S. O. Han. 2003. Cellulosomes from mesophilic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 185:5907-5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fierobe, H. P., A. Mechaly, C. Tardif, A. Belaich, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, J. P. Belaich, and E. A. Bayer. 2001. Design and production of active cellulosome chimeras. Selective incorporation of dockerin-containing enzymes into defined functional complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21257-21261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujino, T., P. Béguin, and J.-P. Aubert. 1993. Organization of a Clostridium thermocellum gene cluster encoding the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipA and a protein possibly involved in attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface. J. Bacteriol. 175:1891-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerngross, U. T., M. P. Romaniec, T. Kobayashi, N. S. Huskisson, and A. L. Demain. 1993. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol. Microbiol. 8:325-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein, M. M., M. Takagi, S. Hashida, O. Shoseyov, R. H. Doi, and I. H. Segel. 1993. Characterization of the cellulose-binding domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A. J. Bacteriol. 175:5762-5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen. C. K. 1992. Fibronectin type III-like sequences and a new domain type in prokaryotic depolymerase with insoluble substrates. FEBS Lett. 2:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton, R. H. 1997. In vitro recombination and mutagenesis of DNA: SOEing together tailor-made genes, p. 141-149. In B. A. White (ed.), PCR cloning protocols from molecular cloning to genetic engineering. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jauris, S., K. P. Rucknagel, W. H. Schwarz, K. P. Bronnenmeier, and W. L. Staudenbauer. 1990. Sequence analysis of the Clostridium stercorarium celZ gene encoding a thermoactive cellulase (Avicelase I): identification of catalytic and cellulose-binding domains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223:258-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen, P. L., and C. K. Hansen. 1990. Multiple endo-beta-1,4-glucanase-encoding genes from Bacillus lautus PL236 and characterization of the celB gene. Gene 93:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakiuchi, M., A. Isui, K. Suzuki, T. Fujino, E. Fujino, T. Kimura, S. Karita, K. Sakka, and K. Ohmiya. 1998. Cloning and DNA sequencing of the genes encoding Clostridium josui scaffolding protein CipA and cellulase CelD and identification of their gene products as major components of the cellulosome. J. Bacteriol. 180:4303-4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kataeva, I. A., R. D. Seidel III, A. Shah, L. T. West, X.-L. Li, and L. G. Ljungdahl. 2002. The fibronectin type 3-like repeat from the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiohydrolase CbhA promotes hydrolysis of cellulose by modifying its surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4292-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyhani, N. O., and S. Roseman. 1996. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33414-33424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosugi, A., K. Murashima, and R. H. Doi. 2001. Characterization of xylanolytic enzymes in Clostridium cellulovorans: expression of xylanase activity dependent on growth substrates. J. Bacteriol. 183:7037-7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosugi, A., K. Murashima, Y. Tamaru, and R. H. Doi. 2002. Cell-surface-anchoring role of N-terminal surface layer homology domains of Clostridium cellulovorans EngE. J. Bacteriol. 184:884-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 277:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibovitz, E., and P. Béguin. 1996. A new type of cohesin domain that specifically binds the dockerin domain of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J. Bacteriol. 178:3077-3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibovitz, E., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, and P. Beguin. 1997. Characterization and subcellular localization of the Clostridium thermocellum scaffolding dockerin binding protein SdbA. J. Bacteriol. 179:2519-2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemaire, M., H. Ohayon, P., Gounon, T. Fujino, and P. Béguin. 1995. OlpB, a new outer layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum, and binding of its S-layer-like domains to components of the cell envelope. J. Bacteriol. 177:2451-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemaire, M., I. Miras, P. Gounon, and P. Béguin. 1998. Identification of a region responsible for binding to the cell wall within the S-layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum. Microbiology 144:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchler-Bauer, A., R. A. Panchenko, B. A. Shoemaker, P. A. Thiessen. L. Y. Geer, and S. H. Bryant. 2002. CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:281-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mesnage, S., T. Fontaine, T. Mignot, M. Delepierre, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 2000. Bacterial SLH domain proteins are non-covalently anchored to the cell surface via a conserved mechanism involving wall polysaccharide pyruvylation. EMBO J. 19:4473-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosbah, A., A. Belaich, O. Bornet, J.-P. Belaich, B. Henrissat, and H. Darbon. 2000. Solution structure of the module X2_1 of unknown function of the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipC of Clostridium cellulolyticum. J. Mol. Biol. 304:201-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murashima, K., A. Kosugi, and R. H. Doi. 2002. Synergistic effects on crystalline cellulose degradation between cellulosomal cellulases from Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 184:5088-5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murashima, K., A. Kosugi, and R. H. Doi. 2003. Solubilization of cellulosomal cellulase by fusion with cellulose-binding domain of noncellulosomal cellulase EngD from Clostridium cellulovorans. Proteins 50:620-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nölling, J., G. Breton, M. V. Omelchenko, K S. Makarova, Q. Zeng, R. Gibson, H. M. Lee, J. Dubois, D. Qiu, J. Hitti, Y. I. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, F. Sabathe, L. Doucette-Stamm, P. Soucaille, M. J. Daly, G. N. Bennett, E. V. Koonin, and D. R. Smith. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:4823-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pages, S., A. Belaich, J. P. Belaich, E. Morag, R. Lamed, Y. Shoham, and E. A. Bayer. 1997. Species-specificity of the cohesin-dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Proteins 29:517-527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pages, S., A. Belaich, H. P. Fierobe, C. Tardif, C. Gaudin, and J. P. Belaich. 1999. Sequence analysis of scaffolding protein CipC and ORFXp, a new cohesin-containing protein in Clostridium cellulolyticum: comparison of various cohesin domains and subcellular localization of ORFXp. J. Bacteriol. 181:1801-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ries, W., C. Hotzy, L. Schocher, U. B. Sleytr, and M. Sára. 1997. Evidence that the N-terminal part of the S-layer protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72/p2 recognizes a secondary cell wall polymer. J. Bacteriol. 179:3892-3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salamitou, S., M. Lemaire, T. Fujino, H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, P. Béguin, and J. P. Aubert. 1994. Subcellular localization of Clostridium thermocellum ORF3p, a protein carrying a receptor for the docking sequence borne by the catalytic components of the cellulosome. J. Bacteriol. 176:2828-2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoseyov, O., and R. H. Doi. 1990. Essential 170 kDa subunit for degradation of crystalline cellulose of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2192-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sleat, R., R. A. Mah, and R. Robinson. 1984. Isolation and characterization of an anaerobic, cellulolytic bacterium, Clostridium cellulovorans sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 48:88-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamaru, Y., and R. H. Doi. 1999. Three surface layer homology domains at the N terminus of the Clostridium cellulovorans major cellulosomal subunit EngE. J. Bacteriol. 181:3270-3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamaru, Y., S. Karita, A. Ibrahim, H. Chan, and R. H. Doi. 2000. A large gene cluster for the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. J. Bacteriol. 182:5906-5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe, T., K. Suzuki, W. Oyanagi, K. Ohnishi, and H. Tanaka. 1990. Gene cloning of chitinase A1 from Bacillus circulans WL-12 revealed its evolutionary relationship to Serratia chitinase and to the type III homology units of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 265:15659-15665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zverlov, V. V., G. V. Velikodvorskaya, W. H. Schwarz, K. Bronnenmeier, J. Kellermann, and W. L. Staudenbauer. 1998. Multidomain structure and cellulosomal localization of the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiohydrolase CbhA. J. Bacteriol. 180:3091-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]