Abstract

The physiological role of the membrane-bound pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum was investigated by the characterization of a mutant strain. Comparisons of growth levels between the wild type and the mutant under different low-potential conditions and during transitions between different metabolisms indicate that this enzyme provides R. rubrum with an alternative energy source that is important for growth in low-energy states.

Pyrophosphatases (PPases) are divided into two groups according to their localization in the cell. Cytosolic PPases are present in nearly all cells; they hydrolyze the inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) produced by biosynthesis of macromolecules, such as proteins and DNA, thus displacing the equilibrium of the PPi-producing reactions (14). Membrane-bound pyrophosphatases are found in the membranes of some organelles, such as acidocalcisomes of trypanosomatids (26), and in plant tonoplast membranes (16). These enzymes utilize the energy of the hydrolyzed anhydride bond of PPi to translocate protons across their respective membranes, generating an electrochemical proton gradient for the active transport of solutes. The membranes of some species of purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacteria also have membrane-bound, proton-translocating PPases (H+PPases). These enzymes hydrolyze and synthesize PPi, generating or consuming an electrochemical proton gradient (1). The H+PPase of Rhodospirillum rubrum is the most intensively studied enzyme of this kind (2, 4, 10, 20, 29), but its physiological role is not completely understood. Nyrén and Strid (19) hypothesized that the main function of the H+PPase of R. rubrum is to maintain the proton motive force in light-grown cells under conditions of low energy. The present work is the first experimental attempt to elucidate the physiological role of the H+PPase in photosynthetic bacteria by using an R. rubrum H+PPase null mutant.

Construction and characterization of H+PPase mutant strain.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Photosynthetic bacteria and derivative strains were grown anaerobically or aerobically in the medium described by Cohen-Bazire (7) at 30°C. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), and gentamicin (15 μg/ml) were added as required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Photosynthetic bacterial strains | ||

| Rhodospirillum rubrum ATCC 11170 | Wild type | |

| RG1 | ATCC 11170 derivative, hpp-960::Kan | This work |

| RG1-P | RG1(pBBR1MCS-5) Gmr | This work |

| RG1-P1 | RG1(pBBR-Hpp-Rr) Kanr Gmr | This work |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. | Wild type | |

| Rhodobacter capsulatus DSM 1710 | Wild type | |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris 2.1.6. | Wild type | |

| Rhodomicrobium vannielii DSM 162 | Wild type | |

| Escherichia coli S17-1 | pro thi hsdR hsdM+recA [RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Kan::Tn7(Tpr Smr) Tra+] | 22 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCRII | 3.9-kb cloning vector, Apr Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pCR-Hpp | pCRII 1.9-kb fragment of hpp | This work |

| pCR-Hpp-K | pCRII-hpp-960::Kan | This work |

| pUC4K | pUC18 derivative, Apr Kanr | 30 |

| pSUP202 | Suicide vector, Mob+ Cmr Apr Tcr | 22 |

| pSUP-Hpp-K | pSUP202 carrying 1.9-kb fragment of hpp-960::Kan, Apr Cmr | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | 4.8-kb cloning vector, Mob+ Gmr | 15 |

| pBBR-Hpp-Rr | pBBR1MCS-5 (hpp) | This work |

hpp, R. rubrum wild-type H+PPase gene.

The hpp gene was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of R. rubrum. The PCR product was cloned into the pCRII plasmid and sequenced. The gene was interrupted by introducing a blunt-ended PstI-cleaved kanamycin resistance cartridge, generating pCR-Hpp-K. The hpp-960::Kan allele was subcloned as an EcoRI fragment into the pSUP202 plasmid, yielding pSUP-Hpp-K. This construction was introduced into R. rubrum by conjugation. The mutant strain was designated RG1. Southern blot and PCR analyses were performed to confirm the interruption. The viability of this mutant showed that the H+PPase is not essential for the growth of R. rubrum, in contrast with the essential cytoplasmic PPase (6, 24).

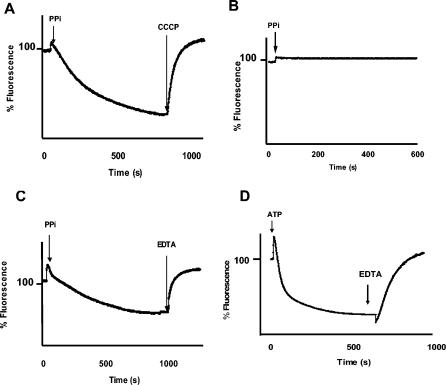

To determine whether the interruption of the hpp gene abolishes PPase activity and PPi-mediated H+-pumping activity, chromatophores from the RG1 mutant strain were isolated. The hydrolytic activity of the mutant was completely abolished with respect to the activity of the wild type (140 nmol of Pi min−1 mg of protein−1). However, hydrolytic activity resumed when the mutant strain was complemented with the wild-type gene from R. rubrum (120% of wild-type hydrolytic activity). Although the plasmid utilized for complementation is a medium-copy-number vector, the expression of extra copies of the gene that may lead to a significant increase in H+PPase activity was not observed in the complemented RG1 mutants. As with activity results, we found that the RG1 mutant failed to exhibit PPi-mediated H+-pumping activity, as monitored by acridine orange fluorescence quenching (Fig. 1A to C), but not when it was quenched with ATP (Fig. 1D). This result indicates that the loss of PPi-supported H+ pumping is due to the lack of the enzyme and not to leakage of H+ across membranes.

FIG. 1.

ΔpH in chromatophores of the different strains. Assay conditions were a solution containing 2 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25 M trehalose, 0.2 M choline chloride, 5 mM MgCl2, 3 μM acridine orange, and 0.5 mg of protein/ml of chromatophores and a temperature of 25°C. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 1 mM PPi (A to C) or 2 mM ATP (D). Gradients were collapsed by the addition of 2.5 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (A) or 5 mM EDTA (C and D). Excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 495 and 540 nm, respectively. (A to C) PPi-dependent ΔpH in the wild type (A), the RG1 mutant (B), and RG1-P1 (complemented mutant) (C); (D) ATP-dependent ΔpH in RG1.

The observed percentage of quenching with PPi in chromatophores of wild-type R. rubrum was 60%, and for the complemented mutant it was around 50%; these percentages correspond to changes in pH (ΔpH) of 1.9 and 1.6 pH units, respectively (according to a calibration plot constructed as described in reference 28 [data not shown]). With ATP, the average percentage of quenching in all strains was 72%, corresponding to a ΔpH of 2.4. The H+PPi and H+ATP stoichiometries reported for R. rubrum chromatophores are 2 and 3.6, respectively (28), explaining the greater acidification obtained with ATP than with PPi. Nevertheless, the PPi-dependent ΔpH might be used to synthesize important amounts of ATP, as was demonstrated previously (11).

Effect of light intensity on RG1 mutant photosynthetic growth.

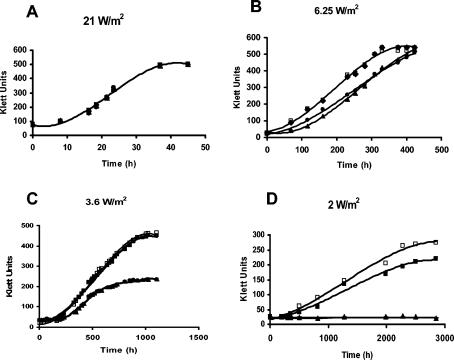

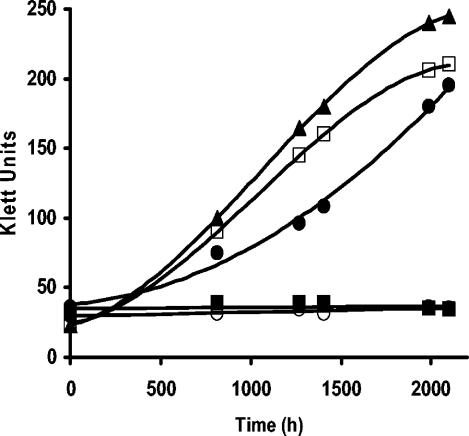

According to the hypothesis of Nyrén and Strid (19), under low-potential conditions, such as low light intensities, the H+PPase of R. rubrum could be used to generate a ΔpH that suffices to maintain bacterial growth. To test this hypothesis, the growth of the mutant was monitored at different light intensities (Fig. 2). At 21 W/m2 (high intensity), the growth of the mutant strain was similar to the growth of the wild type. However, at 6.25 and 3.6 W/m2, the mutant exhibited a considerable delay in growth, and at a very low light intensity (2 W/m2), the RG1 mutant did not grow. The plots of Fig. 2 were used to calculate the replication times and the length of the lag phase at each light intensity (Table 2). No significant differences were observed between the replication times of the mutant and the wild type at light intensities of 21 to 3.6 W/m2. The effect of mutation was on the lag phase. It became longer at light intensities below 21 W/m2, and at an intensity of 2 W/m2, a permanent “latent” lag phase was observed. The mutant strain was able to grow after it was transferred from 2 W/m2 to high light intensity. The particular characteristics of the mutant strain were restored by homologous complementation.

FIG. 2.

Effect of decreasing light intensity on photosynthetic growth of R. rubrum strains. Bacteria were grown in high light intensity before being subcultured and transferred to different light intensities. Light intensity was measured with a YSI-Kettering model 65A radiometer (Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellow Springs, Ohio) and was adjusted by rheostat control of two tungsten 40-W lamps at a 30-cm distance. □, wild type; •, RG1 mutant; ▪, RG1-P1 (complemented mutant); ▴, RG1-P (mutant with empty vector). Growth curves are representative of the results of one of at least four identical experiments.

TABLE 2.

Effect of light intensity on photosynthetic growth

| Light intensity (W/m2) | Generation time (h)

|

Lag phase length (h)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | RG1 | RG1-P1 | Wild type | RG1 | RG1-P1 | |

| 21 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 6.26 | 43.2 | 42.3 | 41.3 | 12 | 72 | 12 |

| 3.6 | 172 | 167 | 160 | 192 | 343 | 192 |

| 2 | 470 | ∞a | 485 | 250 | ∞ | 375 |

∞, the strain did not grow.

These results indicate that the presence of the H+PPase is important for R. rubrum growth under low-energy conditions. Particularly, during growth at very low light intensity, the enzyme seems to be essential during the lag phase to achieve the exponential growth phase. Mechanistically, it could be that during the lag phase at low light, the photosynthetic electron transport H+ gradient is not high enough to synthesize the ATP that is needed to produce all the cellular components required for the low-light adaptation and, therefore, to permit exponential growth. Under these conditions, the H+PPase may hydrolyze PPi, establishing an H+ gradient to generate this critical amount of ATP. During the exponential phase, the contribution of H+PPase may be less prominent, since the activity of the cytoplasmic PPase may become an important factor in the removal of cytoplasmic PPi in order to sustain active growth, leaving less substrate for the H+PPase. In addition, the H+ gradient generated by the photosynthetic electron chain may be the main driving force for the generation of ATP. At 2 W/m2, the H+ gradient from the photosynthetic electron transport chain is very low, so the PPi-dependent H+ gradient produced by H+PPase might become the main energy source. It might also be the main energy source in the exponential growth phase, but this would not be the case for the mutant strain.

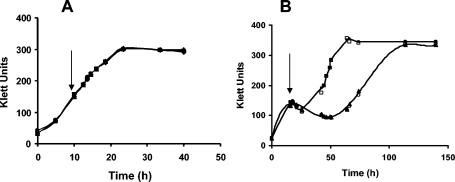

Importance of H+PPase during metabolic shifts.

Purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacteria are very versatile organisms. There are members of this group, such as R. rubrum, that can perform photosynthesis under anaerobic conditions, as well as respiration and fermentation (21). Since H+PPase is present in growing photosynthetic and respiratory cells of R. rubrum (23), we examined whether H+PPase is central in obtaining energy during metabolic shifts. When a photosynthetic to respiratory metabolic shift was imposed (Fig. 3A), all the studied strains grew without an appreciable lag phase. However, in the case of a respiratory to photosynthetic metabolic shift (Fig. 3B), all the strains showed a lag phase, which was considerably longer for the RG1 mutant strain (40 versus 14 h). In this metabolic transition, many of the enzymes and other complex components that are essential for photosynthetic growth, such as chromatophores, are absent. They must be synthesized before growth begins. In fact, the time needed for the synthesis of about 60% of the chromatophores in R. rubrum is the same as the lag phase time observed in wild-type bacteria after the metabolic shift (9). Hence, during adaptation, the H+PPase probably hydrolyzes PPi, providing the energy to synthesize these components, and thus reduces the length of the lag phase.

FIG. 3.

Effect of metabolic shifts in the growth of R. rubrum strains. (A) Photosynthetic to respiratory metabolic shift; (B) respiratory to photosynthetic metabolic shift. To adapt bacteria to the first metabolism, they were subcultivated in it three times before the experiment. The experiment started when the bacteria were transferred to a fresh medium under the same metabolic condition. When the culture reached the early exponential phase, the metabolic shift was imposed (arrow), and it continued until the stationary phase was achieved. Light intensity was 21 W/m2. □, wild type; ○, RG1 mutant; ▪, RG1-P1 (complemented mutant); ▴, RG1-P (mutant with an empty vector).

The lack of an appreciable lag phase during the photosynthetic to aerobic shift might be explained by the fact that bacteria adapt easily to the new metabolism, since almost all the proteins of the respiratory chain are in the photosynthetic chain (probably all but the terminal oxidases).

Effect of a low oxygen concentration on RG1 mutant aerobic growth.

To establish a different low-potential condition that did not depend on light intensity, bacteria were exposed to low oxygen tension during aerobic growth. As expected, at a normal air O2 concentration (about 21%), the growth of the RG1 mutant and that of the wild type were similar. However, the RG1 mutant exhibited a delay in growth when the O2 concentration was lowered to 10% (Fig. 4). Under these conditions, the H+ gradient generated by respiratory electron transport would not suffice to sustain the normal growth of the mutant strain. It is also noted that, similar to the findings under the photosynthetic low-potential condition, normal growth was restored by complementation of the mutant strain (data not shown). These results confirm that, regardless of the mechanism by which the low energy condition is induced, the H+PPase is important for growth.

FIG. 4.

Effect of oxygen tension in aerobic growth of R. rubrum strains. Bacteria were grown in the dark with continuous shaking in a TS Autoflow CO2/O2 incubator (NuAire, Inc). Oxygen levels were controlled by injecting air and N2. Open symbols, 21% O2; filled symbols, 10% O2; ▪, wild type; •, RG1 mutant.

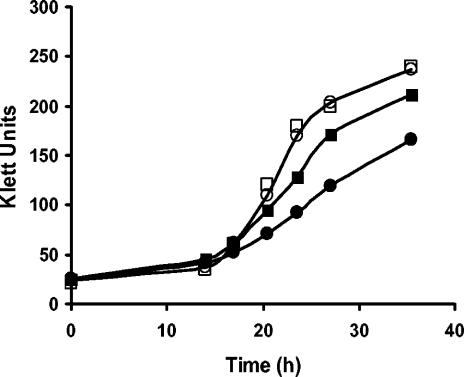

Growth of other photosynthetic purple nonsulfur bacteria at very low light intensity.

Among the purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacteria, there are species, such as R. rubrum, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, and Rhodomicrobium vannielii, that have H+PPase, and others, like Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides, that do not have it (18, 25). Thus, it was considered relevant to explore whether the presence of the H+PPase confers the ability to grow at very low light intensities (2 W/m2), as is the case for R. rubrum (Fig. 2). Figure 5 shows that only those species with H+PPase were able to grow under this condition. Therefore, these data, together with the results with the mutant strain (Fig. 2), suggest that the presence of H+PPase in purple nonsulfur bacteria is central for growing under low light intensity and, probably, under other low-energy conditions. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that other factors, such as differences in the photosynthetic unit sizes and light-gathering abilities among the species, could have contributed to the growth under conditions of low light intensity (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Photosynthetic growth of different species of purple nonsulfur bacteria at a light intensity of 2 W/m2. The species for this experiment were selected based on the presence (□, R. rubrum; •, Rhodopseudomonas palustris; and ▴, Rhodomicrobium vannielii) or absence (○, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and ▪, Rhodobacter capsulatus) of H+PPase in them.

As for physiological implications, these results suggest that in purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacteria, which usually grow in ponds or meromictic lakes exposed to different partial oxygen pressures and variable light intensity (21), the existence of H+PPase is fundamental for development in such changing environments.

It is interesting that all tested species with H+PPase, which grow at very low light intensities, have the classical family I cytoplasmic PPase but that the Rhodobacter species that does not grow under that condition possesses the newly described family II cytoplasmic PPase (5, 24). The structural and biochemical characteristics of both families are very different, but family I cytoplasmic PPase is less active and seems to be highly regulated (5, 12, 13). Whether this type of cytoplasmic enzyme exists only in cells that have H+PPase remains to be elucidated.

It has been proposed that in plants, vacuolar H+PPase may replace vacuolar ATPase under energy stress, such as anoxia and chilling, and in growing tissues to maintain vacuole acidity (3, 8, 17, 27). Under these conditions, plant cells may have some difficulty in obtaining from ATP the needed energy to survive; hence, they utilize PPi (an abundant by-product of anabolism) to generate an electrochemical H+ gradient to safeguard ATP. This work provides evidence that the physiological roles of bacterial enzymes could be the same, that is, to hydrolyze preferentially PPi under low-energy conditions when ATP concentration is low and, therefore, insufficient to cover all the energy requirements of the cell.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by DGAPA grant IN-216401 from UNAM.

We are grateful to Rosa Laura Camarena and Armando Gómez-Puyou for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baltscheffsky, H., L. V. von Stedingk, H. W. Heldt, and M. Klingenberg. 1966. Inorganic pyrophosphate: formation in bacterial photophosphorylation. Science 153:1120-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baykov, A. A., N. V. Sergina, O. A. Evtushenko, and E. B. Dubnova. 1996. Kinetic characterization of the hydrolytic activity of the H+ pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum in membrane-bound and isolated states. Eur. J. Biochem. 236:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carystinos, G. D., H. R. MacDonald, A. F. Monroy, R. S. Dhindsa, and R. J. Poole. 1995. Vacuolar H+-translocating pyrophosphatase is induced by anoxia or chilling in seedlings of rice. Plant Physiol. 108:641-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celis, H., and I. Romero. 1987. The phosphate-pyrophosphate exchange and hydrolytic reactions of the membrane-bound pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum: effects of pH and divalent cations. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 19:255-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celis, H., B. Franco, S. Escobedo, and I. Romero. 2003. Rhodobacter sphaeroides has a family II pyrophosphatase. Comparison with other species of photosynthetic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 179:368-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, J., A. Brevet, M. Fromant, F. Lévêque, J.-M. Schmitter, S. Blanquet, and P. Plateau. 1990. Pyrophosphatase is essential for growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:5686-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen-Bazire, G., W. R. Sistrom, and R. Y. Stainer. 1957. The kinetics studies of pigment synthesis by non-sulfur purple bacteria. J. Cell Comp. Physiol. 49:25-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darley, C. P., J. M. Davies, and D. Sanders. 1995. Chill-induced changes in the activity and abundance of the vacuolar proton-pumping pyrophosphatase from mung bean hypocotyls. Plant Physiol. 109:659-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golecki, J. R., and J. Oelze. 1975. Quantitative determination of cytoplasmic membrane invaginations in phototrophically growing Rhodospirillum rubrum. A freeze-etch study. J. Gen. Microbiol. 88:253-258. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillory, R. J., and R. R. Fisher. 1972. Studies on the light-dependent synthesis of inorganic pyrophosphate by Rhodospirillum rubrum chromatophores. Biochem. J. 129:471-481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keister, D. L., and J. N. Minton. 1971. ATP synthesis driven by inorganic pyrophosphate in Rhodospirillum rubrum chromatophores. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 42:932-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klemme, J. H., and H. Gest. 1971. Regulation of the cytoplasmic pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Eur. J. Biochem. 22:529-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klemme, J.-H., B. Klemme, and H. Gest. 1971. Catalytic properties and regulatory diversity of inorganic pyrophosphatases from photosynthetic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 108:1122-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornberg, A. 1962. On the metabolic significance of phosphorolytic and pyrophosphorolytic reactions, p. 251-264. In H. Kasha and B. Pullman (ed.), Horizons in biochemistry. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 15.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector PBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeshima, M. 2000. Vacuolar H(+)-pyrophosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465:37-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakanishi, Y., and M. Maeshima. 1998. Molecular cloning of vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase and its developmental expression in growing hypocotyls of mung bean. Plant Physiol. 116:589-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nore, B. F., P. Nyrén, G. F. Salih, and A. Strid. 1990. Photosynthetic formation of inorganic pyrophosphate in phototrophic bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 24:75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyrén, P., and A. Strid. 1991. Hypothesis: the physiological role of the membrane-bound proton-translocating pyrophosphatase in some phototrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 77:265-270. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyrén, P., B. F. Nore, and M. Baltscheffsky. 1986. Studies on photosynthetic inorganic pyrophosphate formation by Rhodospirillum rubrum chromatophores. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 851:276-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfennig, N. 1978. General physiology and ecology of photosynthetic bacteria, p. 3-18. In R. Clayton and W. R. Sistrom (ed.), The photosynthetic bacteria. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Priefer, U. B., R. Simon, and A. Pühler. 1985. Extension of the host range of Escherichia coli vectors by incorporation of RSF1010 replication and mobilization functions. J. Bacteriol. 163:324-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero, I., A. Gómez-Priego, and H. Celis. 1991. A membrane-bound pyrophosphatase from respiratory membranes of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2611-2616. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero, I., R. García-Contreras, and H. Celis. 2003. Rhodospirillum rubrum has a family I pyrophosphatase: purification, cloning and sequencing. Arch. Microbiol. 179:377-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarm, H.-M., H. Vigenschow, and K. Knobloch. 1968. Kinetic characterization and partial purification of the membrane-bound inorganic pyrophosphatase from Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 367:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott, D. A., W. de Souza, M. Benchimol, L. Zhong, H. G. Lu, S. N. Moreno, and R. Docampo. 1998. Presence of a plant-like proton-pumping pyrophosphatase in acidocalcisomes of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22151-22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiratake, K., Y. Kanayama, M. Maeshima, and S. Yamaki. 1997. Changes in H+-pumps and a tonoplast intrinsic protein of vacuolar membranes during development of pear fruit. Plant Cell Physiol. 38:1039-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sosa, A., and H. Celis. 1995. H+/PPi stoichiometry of membrane-bound pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316:421-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosa, A., H. Ordaz, I. Romero, and H. Celis. 1992. Magnesium is an essential activator of hydrolytic activity of membrane-bound pyrophosphatase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochem. J. 283:561-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion, mutagenesis, and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]