Abstract

Transcription of the yclJK operon, which encodes a potential two-component regulatory system, is activated in response to oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. Northern blot analysis and assays of yclJ-lacZ reporter gene fusion activity revealed that the anaerobic induction is dependent on another two-component signal transduction system encoded by resDE. ResDE was previously shown to be required for the induction of anaerobic energy metabolism. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and DNase I footprinting experiments showed that the response regulator ResD binds specifically to the yclJK regulatory region upstream of the transcriptional start site. In vitro transcription experiments demonstrated that ResD is sufficient to activate yclJ transcription. The phosphorylation of ResD by its sensor kinase, ResE, highly stimulates its activity as a transcriptional activator. Multiple nucleotide substitutions in the ResD binding regions of the yclJ promoter abolished ResD binding in vitro and prevented the anaerobic induction of yclJK in vivo. A weight matrix for the ResD binding site was defined by a bioinformatic approach. The results obtained suggest the existence of a new branch of the complex regulatory system employed for the adaptation of B. subtilis to anaerobic growth conditions.

Current knowledge about the adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to oxygen limitation in the environment has revealed a redox-dependent regulation of gene expression at the transcriptional level (13, 21, 22, 34). A two-component regulatory system, composed of a histidine sensor kinase (ResE) and a response regulator (ResD), has a pivotal role in the metabolic adjustment required for anaerobic growth, with nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor (23, 31). ResD and ResE are required for the transcription of genes involved in anaerobic nitrate respiration, including fnr (anaerobic gene regulator; Fnr), nasDEF (nitrite reductase operon), and hmp (flavohemoglobin) (9, 12, 19, 23). Furthermore, ResD and ResE also play an important role in another mode of anaerobic growth, i.e., fermentation (3, 18), in which they are required for the full induction of ldh (lactate dehydrogenase) and lctP (lactate permease) expression (3). The genes encoding ResA, ResB, and ResC, which constitute an operon with the genes for ResD and ResE, are thought to be involved in cytochrome c biosynthesis (31). A recent study showed that ResA is required for the reduction of cysteinyl residues during heme binding to apocytochrome c (5). ResD and ResE are also required for the transcription of their own genes, which is initiated at the resA operon promoter (31). Previous studies demonstrated the physical interaction of ResD with the regulatory regions of ctaA (35), resA (35), hmp (20), nasD (20), and fnr (20). ResD activates the transcription of ctaA (25), hmp (8, 24), nasD (8), and fnr (8) in vitro.

The ResD-ResE signal transduction system functions early in the anaerobic gene regulatory cascade. It activates the expression of other regulatory genes that also play important roles in anaerobic gene expression. One such gene encodes Fnr, which is needed for activation of the respiratory nitrate reductase operon narGHJI (2). Fnr also activates the transcription of another regulator gene, arfM. Anaerobic expression of the fermentative operons ldh-lctP (lactate fermentation) and alsSD (acetoin formation) (14) and of the heme biosynthesis genes hemN and hemZ is partly dependent on ArfM (10).

A previous DNA microarray analysis showed that the two-component regulatory genes yclJ (encoding a potential response regulator) and yclK (encoding a potential sensor kinase) are induced by oxygen limitation (34). YclK is likely one of the class IIIA family of kinases according to a classification based on sequence similarities in the vicinity of the phosphorylated histidine. The potential response regulator YclJ belongs to the OmpR family of transcriptional regulators according to alignments of sequences within the C-terminal domains of response regulators (6). A comprehensive DNA microarray analysis was undertaken to identify target genes of uncharacterized B. subtilis two-component regulatory systems (11). Seventeen genes were designated as being positively controlled by YclJK, while 11 appeared to be negatively controlled. For this paper, we examined how yclJK transcription is activated in response to oxygen limitation and determined whether the candidate target genes are regulated by YclJK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All B. subtilis strains used for this work are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani medium was used for standard cultures of B. subtilis and Escherichia coli unless otherwise indicated. For investigations of the expression of various lacZ fusions and for preparations of RNA, the strains were grown at 37°C in minimal medium (80 mM K2HPO4, 44 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1.5 mM thiamine, 40 μM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 68 μM FeCl2 · 4H2O, 5 μM MnCl2 · 4H2O, 12.5 μM ZnCl2, 24 μM CuCl2 · 2H2O, 2.5 μM CoCl2 · 6H2O, 2.5 μM Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 50 mM glucose, 50 mM pyruvate, 1 mM l-tryptophan, 0.8 mM l-phenylalanine), and where indicated, 10 mM nitrate or 10 mM nitrite was added. For aerobic growth, 100 ml of medium was inoculated at an optical density at 578 nm (OD578) of 0.05 with an aerobically grown overnight culture and then incubated in a 500-ml baffled flask with shaking at 250 rpm. For anaerobic fermentative growth, the bacteria were incubated in completely filled flasks with rubber stoppers and with shaking at 100 rpm in an incubation shaker to minimize aggregation of the bacteria. Inoculation was performed aerobically with an aerobically grown overnight culture with an OD578 of 0.3. Anaerobic conditions were achieved after a short time through the consumption of residual oxygen by the inoculated bacteria. After 3 h in the midst of the exponential growth phase and after 6 h at the beginning of the stationary growth phase, samples for β-galactosidase assays were taken. The cells for preparations of RNA were harvested after 3 h in the midst of the exponential growth phase.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used for this study

| B. subtilis strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | BGSCa |

| LAB2135 | trpC2 pheAl ΔresDE::tet | 23 |

| LAB2234 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresE::spec | 18 |

| THB2 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spec | 9 |

| BEH1 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔyclJ::ery | This study |

| BEH2 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH3 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔyclJ::ery amyE::yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH4 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spec amyE::yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH5 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH6 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::muta yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH7 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::mutb yclJ-lacZ cat | This study |

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center.

Construction of B. subtilis yclJK mutant strain.

A 1,197-bp PCR fragment containing parts of the coding region of yclJK was amplified by PCR with primers EH100 5′-GGTTTTGAAGCCGAATTCGTTCATGAC-3′ (the 5′ end corresponds to position 69 of the yclJ coding sequence) and EH101 5′-CGCTTCTCTCAGCTCTAGAATCCGCTTGAC-3′ (the 5′ end corresponds to position 593 of the yclK coding sequence, with two base changes to create an internal XbaI restriction site [underlined]). This fragment was cleaved at an internal KpnI site (positions 106 to 112 of the yclJ coding sequence) and at the XbaI site and ligated into vector pBluescript SK(+) II (Stratagene) digested with the same restriction enzymes. The plasmid was then cut at an internal HindIII restriction site in the yclJK fragment, and an erythromycin resistance gene cassette liberated from the vector pDG646 (7) by HindIII digestion was inserted. The plasmid was transformed into B. subtilis strain JH642 and screened for erythromycin-resistant clones. The desired double-crossover event was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. The resulting mutant strain, BEH1, carries an inactivated yclJ gene.

Preparation of RNA and Northern blot analysis.

For preparations of RNA, 25 ml of cell culture was added to 25 ml of an ice-cold solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM NaN3. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (5 min at 7,155 × g and 4°C). The cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of supernatant, immediately dropped into a Teflon disruption vessel, filled, and precooled with liquid N2. The cells were disrupted with a Mikro-Dismembrator S instrument (B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) for 2 min at 2,600 rpm. The resulting frozen powder was resuspended in 1 ml of prewarmed (50°C) cell lysis solution consisting of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and 0.5% (wt/vol) N-laurylsarcosine. After complete cell lysis, the solution was immediately placed on ice. The RNA was extracted twice with acidic phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 [vol/vol/vol]) and once with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 [vol/vol]). After ethanol precipitation, the RNA pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5)-1 mM EDTA and 20 μl of a solution containing 200 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5), 180 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, and 15 U of DNase I and then was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Twenty microliters of 250 mM EDTA, pH 7.0, was added, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The resulting RNA pellet was dissolved in 50 μl of H2O. For Northern blot analysis, 10 μg of RNA was separated under denaturing conditions in a 1% agarose-670 mM formaldehyde-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) by vacuum blotting. The approximate sizes of the mRNAs were estimated by the use of RNA standards (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Inc.) labeled with digoxigenin. Hybridization and detection was performed as described elsewhere (4). A digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe was synthesized in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase and a 556-bp yclJ-specific PCR fragment as a template, previously amplified with the following primers: EH34, 5′-TATGTACGATGACGGAGATG-3′; and EH35, 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATAAAATTGATAGCCCCATAC-3′.

Construction of reporter gene fusion and site-directed mutagenesis of yclJ regulatory region.

A transcriptional fusion between the E. coli lacZ gene and the yclJ upstream region was constructed. A 545-bp PCR fragment spanning the region from positions −495 to +50 relative to the translational start of yclJK was amplified with the primers EH29 (5′-CGAGGAATTCGCATCAGACACTTT-3′) and EH28 (5′-TAATGGATCCGTCATCGTACATACA-3′). Using the restriction sites for EcoRI and BamHI created by the primers (underlined), we cloned the promoter region of yclJK into the plasmid pDIA5322 (15), resulting in plasmid PyclJ-lacZ. This plasmid was transformed into B. subtilis strains JH642, LAB2135 (ΔresDE) (23), LAB2234 (ΔresE) (18), THB2 (Δfnr) (9), and BEH1 (ΔyclJ), and transformants were screened for double-crossover integration at the amyE locus.

The potential ResD binding sites were changed from TATTTTTTTCATAC to TcTTggTcTCATgC (part a) and from TAGATTGTTCATAT to TcGAggGcTCATgT (part b), respectively (exchanged bases are shown in lowercase). Crossover PCRs were performed with the following two primers containing the desired base exchanges (in bold letters): EH88 (5′-GAAAAAAACATGAGCCCTCGATTTCTAG-3′) and EH89 (5′-CTAGAAATCGAGGGCTCATGTTTTTTTC-3′) for part a and EH86 (5′-TCCAAAGGCATGAGACCAAGATGAAC-3′) and EH87 (5′-GTTCATCTTGGTCTCATGCCTTTGGA-3′) for part b. Two PCR products were generated with primer pairs EH28-EH88 (180 bp) and EH29-EH89 (393 bp) for part a and with primer pairs EH28-EH86 (191 bp) and EH29-EH87 (380 bp) for part b. In a second PCR, we used the first two PCR products as templates and amplified the whole promoter with the primer pair EH28-EH29. The complete promoter fragments were cloned into the plasmid pDIA5322, as described above for the wild-type sequence, resulting in the plasmids pmuta yclJ-lacZ and pmutb yclJ-lacZ. After transformation into B. subtilis strain JH642, strains BEH6 and BEH7 were obtained.

Identification of yclJK transcription start site.

Fifty micrograms of RNA was used for a primer extension analysis of the yclJ transcript. Reverse transcription was initiated from the γ-32P-end-labeled primer EH36 (5′-CGTCATCGTACATACACTAACATTATC-3′) by a standard procedure (1). The sequencing reaction was performed with the same primer. The primer extension products and the sequencing reactions were analyzed in a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate buffer. The dried gel was analyzed by use of a phosphorimager.

Measurement of yclJ-lacZ expression.

For β-galactosidase assays, cells were harvested by centrifugation 3 h after inoculation. β-Galactosidase activities were determined by a standard method and are given in Miller units (16).

Prediction of ResD binding sites.

A model of the ResD binding site was created by computing an information weight matrix with the following equation: Riw = 2 + log2 f(b,l) − e(n) (bits per base), where f(b,l) is the frequency of each base (b) at position l in the aligned binding sites and e(n) is a small sample size correction factor (29). By adding the weights together for various positions in a particular binding site, we could measure the total individual information (Ri) in bits. We employed Virtual Footprint software for pattern searches and the prediction of potential binding sites (17). This program is able to use the information weight matrix model and is connected interactively to the Prodoric database (http://prodoric.tu-bs.de). The sequence logo was created with Web-Logo software (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

The ResD and ResE proteins were overproduced in E. coli carrying pXH22 or pMMN424, respectively, and were purified by chromatography as described previously (20). DNA fragments carrying the yclJ promoter region (−220 to +30 with respect to the yclJ transcription start site) were amplified by PCR with the primers oMN02-201 (5′-GCCTTCATATTCCAAAAG-3′) and oMN02-202 (5′-TATATCCTCCGGTTGTTT-3′) and with JH642 chromosomal DNA as a template. Mutant yclJ promoters were amplified from plasmids pmuta yclJ-lacZ and pmutb yclJ-lacZ with the same oligonucleotides. The primers were 5′ end labeled on the coding and noncoding strands with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. DNA fragments were produced by PCR as described above, but with one labeled and one unlabeled primer. The radiolabeled promoter fragments were separated in 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and then purified in Elutip-d columns (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Unlabeled probes employed in competition experiments were produced by PCR as well and were purified in 1.2% agarose gels, followed by fragment recovery by use of a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

EMSAs were performed by incubating the labeled fragments (0.18 pmol or 1,000 cpm per reaction) with the indicated amounts of the ResD protein, with or without ResE, in 20 μl of reaction buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg of poly(dI-dC)/ml, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA)/ml, 0.25 mM ATP]. After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, the reaction mixtures were separated in 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in Tris-acetate buffer. The gels were dried and analyzed by use of a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). In vitro phosphorylation assays using [γ-32P]ATP showed that ResD was phosphorylated under this conditions.

DNase I footprinting analysis.

The yclJ fragment, labeled as described above (50,000 cpm per reaction), was incubated with 2 to 6 μM ResD and/or ResE protein in the same buffer as that used for EMSAs, except that glycerol, poly(dI-dC), and BSA were omitted. The reaction was treated with 60 ng of DNase I at room temperature for 20 s for free probes and 40 s for reactions containing the protein(s). The same primers used for the labeling of DNA fragments were used for sequencing of the template DNAs with a Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit (USB, Cleveland, Ohio). The sequencing reactions were run together with the footprinting reactions in 8% polyacrylamide-urea gels in Tris-borate buffer. The dried gels were analyzed by phosphorimaging.

In vitro transcription assay.

A mutant ResD protein (D57A) was overproduced in E. coli pMMN539. ResE and wild-type and mutant ResD proteins were chromatographically purified as described previously (8). The linear template of yclJ (−129 to +116) used for in vitro transcription assays was PCR amplified with the primers oHG-11 (5′-CCCCTTGCTGATAAATTAATA-3′) and oHG-12 (5′-AATTCGGCTTCAAAACCTTCT-3′). The PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). In vitro transcription buffer contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM ATP, 50 μg of BSA/ml, 10% glycerol, and 0.4 U of RNasin RNase inhibitor (Promega)/μl. ResD (0.35, 0.7, and 1.4 μM), ResE (1 μM), or both were incubated in 20 μl of transcription buffer at room temperature for 10 min. RNA polymerase and templates were added at final concentrations of 25 and 5 nM, respectively, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. ATP, GTP, CTP (each at 100 μM), UTP (25 μM), and 5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol) were added to start transcription. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, 10 μl of stop solution (1 M ammonium acetate, 100 μg of yeast RNA/ml, 30 mM EDTA) was added. The nucleic acids in the reaction mixture were precipitated with ethanol, and the pellet was dissolved in 3.5 μl of loading dye solution (7 M urea, 100 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue). The transcripts were analyzed in a urea-8% polyacrylamide gel. RNA markers were prepared according to the Decade marker system protocol (Ambion Inc., Austin, Tex.).

RESULTS

Analysis of yclJK operon structure.

In a microarray analysis, the yclJ and yclK genes for a potential two-component system were found to be induced under anaerobic conditions (34). In order to analyze the expression and organization of these genes in detail, we performed a Northern blot analysis. A sequence analysis of the yclJK region showed that the yclK start codon resides eight nucleotides upstream of the yclJ stop codon (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/SubtiList/). The partial overlap between the yclJ and yclK open reading frames suggested that these genes constitute an operon. Northern analysis results listed in the BSORF Bacillus subtilis Genome Database (http://bacillus.genome.ad.jp/) indicated that yclJ and yclK are cotranscribed. We examined whether the two genes are coinduced by anaerobiosis by examining yclJK transcript levels on Northern blot membranes. Equal amounts of total RNAs isolated from wild-type cells cultured under aerobic and three different anaerobic conditions (fermentative, anaerobic with nitrate, and anaerobic with nitrite) were analyzed with a yclJ-specific RNA probe (Fig. 1). A single transcript of 2.1 kb, which corresponds to the size of the yclJK operon, was detected for RNAs isolated from anaerobically grown cells, whereas the transcript was barely detected in RNAs from aerobic cultures. A transcript of the same size was detected with a yclK-specific probe (data not shown). The yclJK transcript was not present in RNA prepared from a resDE mutant strain that was grown anaerobically. This result clearly demonstrated that the anaerobic induction of yclJK is dependent on resDE. The Northern blot analysis showed that yclJ and yclK are likely cotranscribed from a promoter residing upstream of the yclJ gene. The transcription start site was identified by primer extension analysis (Fig. 2). Upstream of the transcription start site a potential σA-type −10 (TATTAT) sequence was detected, but no sequence resembling a −35 region was present, suggesting the involvement of an additional activator for efficient transcription of yclJK.

FIG. 1.

Anaerobic expression of yclJK operon is ResDE dependent. Total RNAs were extracted from wild-type strain JH642 and the resDE mutant strain LAB2135 grown under the following growth conditions: aerobic (1), fermentative (2), anaerobic plus nitrate (3), and anaerobic plus nitrite (4). RNAs (10 μg) were separated in a 1% denaturing agarose gel and analyzed by Northern blotting. A yclJ-specific RNA probe was used for hybridization. A single transcript of 2.1 kb was detected, which corresponds to the size of a yclJK transcript. Ethidium bromide staining of the gel showed that equal amounts of RNA were analyzed. The size standards are RNA molecular weight marker no. 1 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and the 16S and 23S rRNA species.

FIG. 2.

Determination of transcription start site of yclJK by primer extension analysis. The total RNA was isolated and analyzed from JH642 cells grown aerobically (1) and under fermentative conditions (2). The same primer used for the primer extension analysis was used for sequencing reactions (lanes G, A, T, and C). Arrows indicate the primer extension products and asterisks mark the 5′ end of the yclJK mRNA in the sequence.

Examination of yclJ-lacZ expression in various regulatory mutant strains.

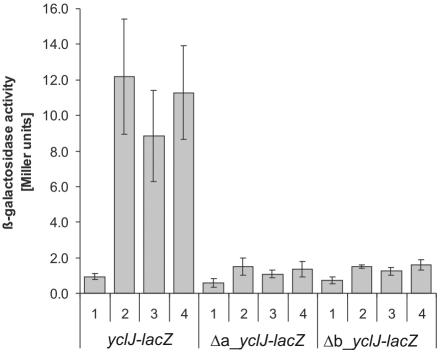

To gain further insights into the regulation of yclJK transcription, we fused the promoter region of yclJ to a promoterless E. coli lacZ gene. The expression of yclJ-lacZ in wild-type cells was induced 8- to 10-fold under all employed anaerobic conditions compared to aerobic conditions (Fig. 3). In accordance with the results of the Northern blot analysis, the introduction of the resDE mutation completely abolished the anaerobic induction of yclJK. Only a residual expression of yclJ-lacZ was found in a resE mutant strain, indicating that the phosphorylation of ResD by ResE is required for the anaerobic induction of yclJK (Fig. 3). In contrast to the effect observed for the resDE mutant, mutations in fnr had no significant effect on yclJ-lacZ expression. In agreement with this finding, no obvious Fnr binding site was detected in the yclJK promoter region. The expression level of yclJ-lacZ in an arfM mutant strain was similar to the wild-type level as well (data not shown). These results indicate that ResDE does not exert its positive role through Fnr or ArfM and that it may play a more direct role in yclJK activation. The β-galactosidase activity in a yclJ mutant was reduced by half compared to that in the wild type, suggesting that yclJK expression is under moderate autoregulatory control. Nevertheless, ResD is the essential regulator of yclJK expression. YclJK is able to increase yclJK expression to some extent, but only in cooperation with ResD. Therefore, a resD mutation abolishes the expression of yclJK.

FIG. 3.

Expression of yclJ-lacZ in various regulatory mutant strains. β-Galactosidase activities were measured in the JH642 wild-type strain and resDE, resE, fnr, and yclJ mutant strains after 3 h of culture under the following growth conditions: aerobic (1), fermentative (2), anaerobic plus nitrate (3), and anaerobic plus nitrite (4). Error bars indicate standard deviations (n ≥ 3).

ResD binds to the yclJ promoter.

We examined by EMSA the possibility that ResD directly binds to the yclJ promoter. A 250-bp DNA fragment carrying the yclJ promoter (positions −220 to +30) was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and incubated with increasing amounts of purified recombinant ResD in the presence or absence of ResE, followed by electrophoresis in order to resolve DNA-protein complexes (Fig. 4A). The results indicated that ResD forms a stable complex with the yclJ promoter. However, the phosphorylation of ResD via ResE only slightly stimulated DNA binding.

FIG. 4.

EMSAs to detect binding of ResD to yclJ promoter. (A) An end-labeled DNA fragment containing the yclJ promoter was incubated with ResD in the presence (ResD-P) or absence (ResD) of 0.5 μM ResE. The amounts of ResD used were 0.06 μM (lanes 2 and 6), 0.13 μM (lanes 3 and 7), 0.25 μM (lanes 4 and 8), and 0.5 μM (lanes 5 and 9). Lane 1, probe only. (B) ResD does not bind to yclJ promoters carrying mutations in the putative ResD box. The same DNA fragments containing the wild-type and mutant promoters were used to examine interactions with ResD phosphorylated with 0.5 μM ResE. The ResD concentrations used were 0.13 μM (lanes 2, 5, and 8), 0.25 μM (lanes 3, 6, and 9), and 0.5 μM (lanes 4, 7, and 10). Lane 1, probe only. (C) Competition experiment with cold DNA fragment containing the wild-type and mutant promoters. The labeled yclJ promoter fragment was incubated with 0.5 μM ResD and ResE (lane 2). Increasing amounts of cold DNA, i.e., 2.5 nM (lanes 3, 6, and 9), 5 nM (lanes 4, 7, and 10), and 10 nM (lanes 5, 8, and 11), were included as competitor DNA in the reaction mixtures. Lane 1, probe only. The image shows the effect of the mutations in the putative ResD box on binding by ResD. Probes muta and mutb indicate the yclJ promoter carrying the binding site a and binding site b mutations, respectively.

To localize the ResD binding site in the yclJ promoter, we performed DNase I footprinting analysis (Fig. 5). A strongly protected area between positions −92 and −73 relative to the transcription start site was observed on both strands, and ResD-P protected the same regions with a similar affinity as unphosphorylated ResD.

FIG. 5.

DNase I footprinting experiment with ResD and the yclJ promoter. Increasing concentrations of ResD and/or ResE (2, 4, 8, and 16 μM) were incubated with 32P-end-labeled coding and noncoding strands of the yclJ promoter. G and A sequencing ladders are included to localize the binding sites. The vertical brackets indicate protected regions. Dotted brackets show weakly protected regions. Positions relative to the transcription start site are shown.

Phosphorylation of ResD by ResE is needed for maximal transcriptional activation of yclJK.

Since the binding of ResD to the yclJ promoter was not stimulated by phosphorylation, we investigated whether phosphorylation is mainly required for transcriptional activation by using an in vitro transcription assay. In the absence of ResD and ResE, the transcript of yclJ was barely detected (Fig. 6, lane 1). Increasing amounts of unphosphorylated ResD only slightly stimulated in vitro transcription (Fig. 6, lanes 2 to 4). However, in vitro transcription was significantly stimulated when both ResD and ResE were present (Fig. 6, lanes 5 to 7). This indicated that the phosphorylation of ResD is required for full transcriptional activation. It was shown previously that the aspartate residue at position 57 of ResD is the phosphorylation site of the response regulator. A mutant ResD protein carrying an amino acid exchange at position 57 from aspartate to alanine (D57A) can no longer be phosphorylated by ResE (8). To further determine the effect of ResD phosphorylation on yclJK transcription in vitro, we tested the mutant ResD D57A protein with the in vitro transcription assay. Transcription was stimulated by the mutant ResD D57A protein to a small extent, similar to that by unphosphorylated wild-type ResD (Fig. 6, compare lanes 2 to 4 with lanes 8 to 10). Moreover, the level of the yclJK transcripts was not further increased by ResD D57A in the presence of ResE (Fig. 6, lanes 11 to 13). These results clearly demonstrated that unphosphorylated ResD, although it binds to the promoter region, is not sufficient to activate the maximal transcription of yclJK. The low level of transcription that was activated by unphosphorylated ResD and the D57A mutant was likely due to the phosphorylation-independent activation of ResD as previously described (8). These results, together with the results of the yclJ-lacZ expression analysis with the resE mutant strain, showed that the phosphorylation of ResD by ResE is required for full anaerobic induction of yclJK.

FIG. 6.

In vitro transcription analysis of yclJ promoter. Transcription was carried out with 25 nM purified RNA polymerase and 5 nM templates without ResD and ResE (lane 1), with increasing amounts of wild-type ResD (lanes 2 to 4), with wild-type ResD and ResE (lanes 5 to 7), with the D57A mutant ResD (lanes 8 to 10), with the D57A mutant ResD and ResE (lanes 11 to 13), and with ResE only (lane 14). The amounts of ResD used were 0.35, 0.7, and 1.4 μM, and the amount of ResE used was 1 μM. An RNA size marker (in nucleotides) is shown (M).

New definition of ResD binding sites by a bioinformatic approach.

We used an extended information weight matrix model to find a better definition of ResD binding sites. The DNA binding regions of ResD defined by footprinting analyses are part of the Prodoric database (17). They were used to create a weight matrix model, which is presented as a sequence logo (Fig. 7A) (30). The newly defined sequence is 21 bp long, with two stretches of conserved residues, specifically TTGT (positions 4 to 7) and TTTT (positions 13 to 16). The information content of these sequences is higher than 1, indicating the occurrence of major groove contacts with the DNA helix (30). The spacing of 10 between the conserved regions corresponds to one turn of the DNA helix and is typical for DNA binding motifs. The formerly proposed consensus recognition sequence for ResD, TTTGTGAAT (20, 35), corresponds to the first part of the newly defined binding sequence. In the yclJ promoter, the binding motif was detected on the opposite strand at positions −74 to −94 (Fig. 7B) and corresponds to the protected region from the footprinting analysis (Fig. 5).

FIG. 7.

New definition of ResD binding site and location in the yclJ promoter. (A) Sequence logo of the ResD binding site based on the information weight matrix model. The height of each stack of letters is the sequence conservation, measured in bits of information according to the equation given in Materials and Methods. The height of each letter within a stack is proportional to its frequency at that position in the binding site. The letters are sorted, with the most frequent on top. (B) ResD-dependent promoter of yclJ. The transcription start site obtained from primer extension analysis is marked “+1.” Potential ResD binding sites, a and b, are boxed, and their positions with respect to the transcriptional start sites are given. The solid line marks the protected region from the footprinting experiments; the dashed lines mark weakly protected regions. RBS, ribosome-binding site.

Mutagenesis studies of yclJ promoter.

Although ResD binds directly to several promoters, no detailed mutagenesis study of the ResD binding sequence is available. Based on the new computer-aided model of the ResD binding site, we exchanged three highly conserved T and two A residues in each binding part. The two mutated promoters were fused to lacZ and tested for β-galactosidase activity as described above. Both series of mutations almost completely abolished the anaerobic induction of yclJ-lacZ (Fig. 8), indicating that the mutated regions bear one or more nucleotide substitutions that impair ResD-dependent activation. These results suggest that the mutationally altered sequence contains the site of the ResD-DNA interaction. Confirmation of the new consensus awaits more detailed mutational analysis. To examine whether ResD binds to the mutant promoters, we performed EMSAs with the yclJ promoter containing the mutated a and b ResD binding sites. A concentration of 0.5 μM ResD was sufficient for almost complete binding to the wild-type yclJ promoter fragment, but this concentration of ResD resulted in little, if any, binding to the mutant yclJ promoters (Fig. 4B). A competition experiment using excess cold DNA showed that the wild-type DNA fragment, at concentrations as low as 2.5 nM, showed significant competition with the labeled probe. In contrast, a 10 nM concentration of the mutant yclJ promoters failed to compete for ResD binding to the yclJ promoter (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 8.

Mutations in binding sites a and b prevent expression of yclJ-lacZ. β-Galactosidase activities were measured from yclJ-lacZ wild-type and mutant promoter constructs in the JH642 wild-type strain after 3 h of culture under the following growth conditions: aerobic (1), fermentative (2), anaerobic plus nitrate (3), and anaerobic plus nitrite (4). Error bars indicate standard deviations (n ≥ 3).

The YclJK regulon.

To investigate the potential participation of YclJK in anaerobic growth processes, we analyzed the phenotype caused by an yclJ mutation. The deletion of yclJ had no obvious influence on aerobic or anaerobic growth. Moreover, the processes of sporulation and competence were not influenced by the yclJ mutation (data not shown). Subsequently, we analyzed the expression of several genes which are known to play an important role in the anaerobic metabolism of B. subtilis. The expression of narG (nitrate reductase), nasD (nitrite reductase), arfM (modulator of anaerobic respiration and fermentation), hmp (flavohemoglobin), ldh (l-lactate dehydrogenase), and alsS (alpha-acetolactate synthase) was studied by using reporter gene fusions in the yclJ mutant strain during aerobic and anaerobic growth. However, the yclJ mutation had no significant effect on the expression of any of these genes (data not shown).

A previous DNA microarray study identified genes that are possibly regulated by YclJK (11). Candidate genes activated by YclJK were gerKB, pyrR, dhbA, dhbB, fhuD, and several genes of unknown function. Those repressed by YclJK included acoA, acoB, acoC, acoL, atpA, atpD, atpE, qoxB, and qoxC. Since dhbA and dhbB, which are involved in siderophore 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate biosynthesis (26), were shown to be induced by oxygen limitation (34), we tested whether these genes are regulated by YclJK. The expression of a dhbA-lacZ reporter gene fusion (27) was examined in the wild type and the yclJ mutant strain during aerobic and anaerobic growth. As expected, dhbA-lacZ expression was higher upon anaerobic cultivation. However, the higher level of anaerobic expression was not dependent on YclJ (data not shown). The yclI gene was also reported to be activated by YclJK (11). Since yclI is transcribed divergently from the yclJK operon, one might expect that its expression would be affected by YclJK. We constructed an yclI-lacZ reporter gene fusion and compared the β-galactosidase activities of wild-type cells and the yclJ mutant strain cultivated under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The expression of yclI-lacZ was two- to threefold higher under anaerobic conditions than under aerobic conditions. However, there was no significant difference in observed expression between the wild-type and yclJ mutant strains.

The qoxB and qoxC genes, which were identified as being negatively affected by YclJK, encode subunits of cytochrome aa3 quinol oxidase. They are transcribed from the qoxA promoter (28). An examination of a qoxA-lacZ reporter gene fusion revealed that YclJK does not affect expression of the qox operon.

The discrepancy between the results of our lacZ reporter gene experiments and the DNA microarray analysis described by Kobayashi and coworkers was most likely caused by the different experimental conditions employed. For their DNA microarray analysis, Kobayashi et al. overproduced the response regulator YclJ in the absence of the sensor kinase YclK under aerobic conditions. This strategy is applicable to certain classes of two-component regulatory systems, such as CitST and DesKR. However, it is not applicable to others. For example, the overproduction of ResD in the absence of ResE does not result in activation of the ResDE regulon under anaerobic conditions (M. M. Nakano, unpublished result).

In order to identify genes of the YclJK regulon, we isolated RNAs from the wild type and a yclJK mutant grown under a variety of anaerobic conditions and then performed various DNA microarray analyses. Since yclJK is almost exclusively expressed under anaerobic conditions, the stimulus for the YclJK system might be present only under anaerobic conditions. As expected from the initial lacZ fusion analysis described above, the expression of the genes identified as YclJK targets in the previous microarray experiment (11) was not significantly affected by the yclJ mutation in our microarray experiment (data not shown). Moreover, in six independent microarray tests, we reproducibly detected only minor changes of less than twofold in the transcriptional profiles when the wild type and the yclJ mutant were compared. The only exception was the expression of the yclJK operon itself, which was found to be repressed by a factor of about 30 in the yclJ mutant, which is in agreement with the results for yclJ-lacZ reporter gene expression. Besides yclJK itself, no target genes of YclJK have been identified.

DISCUSSION

The ResD-ResE signal transduction system plays an important role in the anaerobic metabolism of B. subtilis and probably other low-GC-content gram-positive bacteria (22). A recent genome sequence analysis has shown that ResD orthologs exist in other gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus stearothermophilus, Bacillus halodurans, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus (NCBI Microbial Genome BLAST databases). The resD and resE orthologs of S. aureus, srrAB (or srhSR), participate in the regulation of energy metabolism in response to variations in oxygen tension (32) and in the control of virulence factor expression (33). An srhSR mutant exhibited reduced survival in animal hosts (33). In this paper, we have shown that ResDE regulates the anaerobic induction of the potential two-component yclJK system. Northern blot, reporter gene fusion, and in vitro transcription experiments showed that ResD upregulates yclJK transcription upon oxygen limitation. EMSA and DNase I footprinting experiments demonstrated a ResD interaction with the yclJ promoter region. Although the phosphorylation of ResD only slightly enhanced binding to the yclJ promoter, in vitro transcription experiments showed that the phosphorylation of ResD greatly stimulates yclJ transcription. It is likely that the phosphorylation of ResD affects the interaction of ResD with RNA polymerase at the yclJ promoter.

We proposed a putative ResD binding site by using a bioinformatic approach. ResD likely binds as a dimer to the 21-bp sequence of the ResD box consisting of two tandemly arranged 10-bp half-sites (Fig. 7A). In the 21-bp sequence, positions 4, 5, 7, 14, and 15 were the most conserved. Position 6 is usually a G (but is a C in one of the ResD binding sites in ctaA), and positions 16 and 18 are occupied by T, except for an A in nasD. Stretches of sequences from positions 1 to 3 (ATT) and positions 9 to 11 (ACA) are identical only in hmp and nasD. Among known members of the ResDE regulon, the oxygen-dependent induction of hmp and nasD is the highest. It remains to be examined whether these sequences are important for the high-affinity binding of ResD to these promoters.

The physiological role of YclJK remains unsolved. Which signal is transmitted by the YclJK regulatory system and whether its involvement in gene regulation is related to anaerobiosis are still unknown. The yclJ mutant showed no obvious growth defect when it was tested under various aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The yclJ mutant was able to grow well under anaerobic conditions that facilitated either nitrate respiration or fermentation (data not shown). Mutant phenotypes of yclJ are not observed in studies listed in the BSORF Bacillus subtilis Genome Database. We also examined the effect of the yclJ mutation on the expression of genes that were predicted to be regulated by YclJK according to a previously reported DNA microarray analysis (11), and we examined DNA arrays ourselves. Our results with promoter-lacZ fusions showed that none of the genes tested was significantly regulated by yclJK under the growth conditions used. It is possible that oxygen limitation, which activates yclJK transcription, is not sufficient to activate the YclJK signal transduction system. Further studies are needed to identify the signal that is transmitted by YclJK, the genes that are regulated by YclJK, and the physiological role of YclJK in B. subtilis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Glaser and John Helmann for their kind gifts of bacterial strains. We also thank Peter Zuber and Shunji Nakano for valuable discussions and Peter Zuber for critical reading of the manuscript.

The work performed in Oregon was supported by grants MCB0110513 from the National Science Foundation and 2000223 from the Partners in Science Program of the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. The work performed in Germany was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ha3456-1/1) and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Cruz Ramos, H., L. Boursier, I. Moszer, F. Kunst, A. Danchin, and P. Glaser. 1995. Anaerobic transcription activation in Bacillus subtilis: identification of distinct FNR-dependent and -independent regulatory mechanisms. EMBO J. 14:5984-5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz Ramos, H., T. Hoffmann, M. Marino, H. Nedjari, E. Presecan-Siedel, O. Dressen, P. Glaser, and D. Jahn. 2000. Fermentative metabolism of Bacillus subtilis: physiology and regulation of gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182:3072-3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engler-Blum, G., M. Meier, J. Frank, and G. A. Müller. 1993. Reduction of background problems in nonradioactive Northern and Southern blot analyses enables higher sensitivity than 32P-based hybridizations. Anal. Biochem. 210:235-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlendsson, L. S., R. M. Acheson, L. Hederstedt, and N. E. Le Brun. 2003. Bacillus subtilis ResA is a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase involved in cytochrome c synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17852-17858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabret, C., V. A. Feher, and J. A. Hoch. 1999. Two-component signal transduction in Bacillus subtilis: how one organism sees its world. J. Bacteriol. 181:1975-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guérout-Fleury, A., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao, G., S. Nakano, and M. M. Nakano. 2004. Transcriptional activation by Bacillus subtilis ResD: tandem binding to target elements and phosphorylation-dependent and -independent transcriptional activation. J. Bacteriol. 186:2028-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann, T., N. Frankenberg, M. Marino, and D. Jahn. 1998. Ammonification in Bacillus subtilis utilizing dissimilatory nitrite reductase is dependent on resDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:186-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homuth, G., A. Rompf, W. Schumann, and D. Jahn. 1999. Transcriptional control of Bacillus subtilis hemN and hemZ. J. Bacteriol. 181:5922-5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi, K., M. Ogura, H. Yamaguchi, K. Yoshida, N. Ogasawara, T. Tanaka, and Y. Fujita. 2001. Comprehensive DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis two-component regulatory systems. J. Bacteriol. 183:7365-7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaCelle, M., M. Kumano, K. Kurita, K. Yamane, P. Zuber, and M. M. Nakano. 1996. Oxygen-controlled regulation of flavohemoglobin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3803-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino, M., T. Hoffmann, R. Schmid, H. Möbitz, and D. Jahn. 2000. Changes in protein synthesis during the adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to anaerobic growth conditions. Microbiology 146:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marino, M., H. C. Ramos, T. Hoffmann, P. Glaser, and D. Jahn. 2001. Modulation of anaerobic energy metabolism of Bacillus subtilis by arfM (ywiD). J. Bacteriol. 183:6815-6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin-Verstraete, I., M. Debarbouille, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1992. Mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis “-12, -24” promoter of the levanase operon and evidence for the existence of an upstream activating sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 226:85-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Münch, R., K. Hiller, H. Barg, D. Heldt, S. Linz, E. Wingender, and D. Jahn. 2003. PRODORIC: prokaryotic database of gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:266-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano, M. M., Y. P. Dailly, P. Zuber, and D. P. Clark. 1997. Characterization of anaerobic fermentative growth in Bacillus subtilis: identification of fermentation end products and genes required for growth. J. Bacteriol. 179:6749-6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano, M. M., T. Hoffman, Y. Zhu, and D. Jahn. 1998. Nitrogen and oxygen regulation of Bacillus subtilis nasDEF encoding NADH-dependent nitrite reductase by TnrA and ResDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:5344-5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano, M. M., Y. Zhu, M. LaCelle, X. Zhang, and F. M. Hulett. 2000. Interaction of ResD with regulatory regions of anaerobically induced genes in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1198-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 1998. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:165-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 2001. Anaerobiosis, p. 393-404. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Nakano, M. M., P. Zuber, P. Glaser, A. Danchin, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3796-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano, S., M. M. Nakano, Y. Zhang, M. Leelakriangsak, and P. Zuber. 2003. A regulatory protein that interferes with activator-stimulated transcription in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4233-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul, S., X. Zhang, and F. M. Hulett. 2001. Two ResD-controlled promoters regulate ctaA expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:3237-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowland, B. M., T. H. Grossman, M. S. Osburne, and H. W. Taber. 1996. Sequence and genetic organization of a Bacillus subtilis operon encoding 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate biosynthetic enzymes. Gene 178:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowland, B. M., and H. W. Taber. 1996. Duplicate isochorismate synthase genes of Bacillus subtilis: regulation and involvement in the biosyntheses of menaquinone and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate. J. Bacteriol. 178:854-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santana, M., F. Kunst, M. F. Hullo, G. Rapoport, A. Danchin, and P. Glaser. 1992. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and physiological characterization of the qox operon from Bacillus subtilis encoding the aa3-600 quinol oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10225-10231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider, T. D. 1997. Information content of individual genetic sequences. J. Theor. Biol. 189:427-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider, T. D., and R. M. Stephens. 1990. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:6097-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun, G., E. Sharkova, R. Chesnut, S. Birkey, M. F. Duggan, A. Sorokin, P. Pujic, S. D. Ehrlich, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1374-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Throup, J. P., F. Zappacosta, R. D. Lunsford, R. S. Annan, S. A. Carr, J. T. Lonsdale, A. P. Bryant, D. McDevitt, M. Rosenberg, and M. K. Burnham. 2001. The srhSR gene pair from Staphylococcus aureus: genomic and proteomic approaches to the identification and characterization of gene function. Biochemistry 40:10392-10401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, and P. M. Schlievert. 2001. Identification of a novel two-component regulatory system that acts in global regulation of virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1113-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye, R. W., W. Tao, L. Bedzyk, T. Young, M. Chen, and L. Li. 2000. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 182:4458-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, X., and F. M. Hulett. 2000. ResD signal transduction regulator of aerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis; cta promoter regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1208-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]