Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae is one of a growing number of bacteria in which the natural ability to uptake exogenous DNA for potential genomic transformation has been recognized. To date, several operons involved in transformation in this organism have been described. These operons are characterized by a conserved 22-bp regulatory element upstream of the first gene and are induced coincident with transfer from rich to nutrient-depleted media. The previously identified operons comprised genes encoding proteins that include members of the type II secretion system and type IV pili, shown to be essential for transformation in other bacteria, and other proteins previously identified as required for transformation in H. influenzae. In the present study, three novel competence operons were identified by comparative genomics and transcriptional analysis. These operons have been further characterized by construction of null mutants and examination of the resulting transformation phenotypes. The putative protein encoded by the HI0366 gene was shown to be essential for DNA uptake, but not binding, and is homologous to a protein shown to be required for pilus biogenesis and twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. An insertion in HI0939 abolished both DNA binding and uptake. The predicted product of this gene shares characteristics with PulJ, a pseudopilin involved in pullulanase export in Klebsiella oxytoca.

Haemophilus influenzae is the etiological agent of several human diseases, including meningitis, otitis media, and respiratory infections in patients with predisposing conditions such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (19, 51, 57).

This species is among a large number of organisms, including other members of the family Pasteurellaceae, that are capable of internalizing exogenous DNA for incorporation into the bacterial chromosome, a process termed transformation (17, 23, 24, 58). In the well-characterized strain Rd KW20, an acapsular derivative of a type d strain (1), a state of transformation competence develops spontaneously with an increase in transformation frequency rising from 10−8 during early-log-phase growth to 10−4 in late-log-phase cells (49). The transformation frequency can be further increased by transfer into a nutrient-depleted medium (27) or by transient anaerobiosis (21, 22). Transformation of H. influenzae has been observed in vivo in diffusion chambers implanted in the peritoneal cavity of rats (14), and a recent study reported horizontal transfer of ompP2 gene sequences between H. influenzae strains colonizing the respiratory tract of a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (29). Competence and transformation may be important contributors to the evolution of virulence. The ability to exchange genetic material between colonizing organisms could result in the acquisition of new virulence determinants and altered alleles, contributing to avoidance of the host defenses. Alternatively, competence ability in H. influenzae could also enhance adaptation to the host during colonization by providing nucleotides as an alternate nutrient source.

Development of competence in H. influenzae requires conditions in which cell division is slowed, but protein synthesis continues (48, 54). Maximal levels of competence in vitro (transformation frequency of 10−3 to 10−2) occur coincident with a transition from rich medium to a nongrowth starvation medium such as MIV (28). This finding suggests that competence development is related to the nutritional state of the cells. Additional evidence of the role of nutrition in competence includes the observation that moderate levels of competence develop spontaneously in late-log-phase cultures (10−4 transformation frequency) but can be induced in early-log-phase cultures by the addition of cyclic AMP (cAMP) (62). Furthermore, the addition of purine precursors to MIV has an inhibitory effect on competence development (36).

Most of the operons containing genes known to be directly involved in DNA uptake and transformation in H. influenzae have a conserved 22-bp palindromic element called the competence regulatory element (CRE) directly upstream of the transcriptional start sites (32, 35). The product of HI0601 tfoX (sxy) is required for transcription of operons containing the CRE, and insertions into tfoX completely abolish transformation development (32, 61, 63). Adenylate cyclase, encoded by the cya gene, is also required for competence development but the transformation-defective phenotype expressed by the cya mutant can be suppressed by addition of exogenous cAMP (15). Competence development is also eliminated by mutations in crp, the gene encoding the cAMP-receptor protein (CRP), but cannot be restored by treatment with exogenous cAMP (9). It has been suggested that CRE sites share significant similarities to CRP binding sites and that the cAMP-CRP complex might activate transcription of transformation genes by binding to the CRE in association with a competence-specific factor such as TfoX (35).

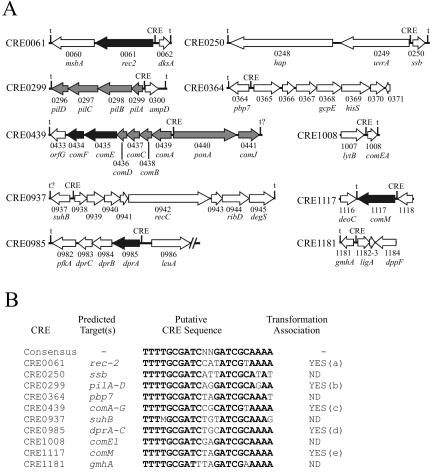

Ten putative CRE sites in the Rd KW20 genome have been previously identified (Fig. 1). Mutational analysis of genes in five of these operons has confirmed a role of those genes in transformation in H. influenzae. While many of the CRE sites are located between divergently transcribed operons, divergent transcription from a CRE site has not been described. We applied in silico, transcriptional, and mutational analyses to characterize three of the previously unexamined CRE regions (CRE0364, CRE0937, and CRE1181) to determine their role in transformation in H. influenzae.

FIG. 1.

Putative CRE regions in H. influenzae Rd KW20. (A) Organization of ORFs contiguous to the putative CRE elements in the Rd KW20 genome. CRE numbers assigned are based upon the original designation of the predicted targeted gene (35). Genes shown with black arrows indicate biological data confirming their role in transformation in H. influenzae. Genes with arrows shaded gray indicate mutations affecting transformation exist in the operon; polar effects prevented individual characterization. White arrows indicate genes for which no data exist to indicate involvement in competence and transformation in H. influenzae. CRE0937 was originally designated a CRP binding site (35). Putative terminators are designated t. (B) Comparison of the putative CRE sequences in the Rd KW20 genome and association with transformation in H. influenzae. ND, role undetermined. Lowercase letters in parentheses indicate references consulted, as follows: a, 13; b, 16; c, 56, d, 33, e, 25. For further information, see reference 13.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

All bacterial growth media were obtained from BBL/Difco (Becton Dickenson, Sparks, Md.). H. influenzae strains were cultured at 37°C on chocolate II agar or brain heart infusion (BHI) agar supplemented with 10 μg of heme/ml and 10 μg of β-NAD/ml (supplemented BHI; sBHI). Liquid cultures were grown in sBHI broth. Escherichia coli strains were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Burtani (LB) broth or LB agar. See Table 1 for the antibiotic concentrations that were used. LB agar was supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) at 40 μg/ml when appropriate.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. colia | ||

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recAI deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7397 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | F− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 recA1 deoR hsdR17 (rK− mK+) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 endA1 | Invitrogen |

| H. influenzaeb | ||

| Rd KW20 | Capsule deficient type d derivative, sequenced strain | ATCC; 1, 18 |

| MAP9 | Rd derivative containing multiple antibiotic resistance alleles, Novr | D. McCarthy; 7, 38 |

| Rec-1 | Rd rec1 | J. Setlow; 4, 52 |

| HI1923 | Rd KW20, HI0939::SPEC Spr | This study |

| HI1924 | Rd KW20, ΔligA Spr | This study |

| HI1925 | Rd KW20, HI0365::SPEC Spr | This study |

| HI1926 | Rd KW20, ΔHI0366 Spr | This study |

| HI1942 | HI1926, pTV30 Spr Cmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | 3.9-kbp TA cloning vector, Plac lacZα Apr Kmr F1 origin, ColE1 origin | Invitrogen |

| pSPECR | pCR-Blunt containing a 1.2-kbp Spr cassette (SPEC) | 60 |

| pUC18N | pUC18 with a NotI linker added at the Hind III site | 55 |

| pSU2718 | E. coli-H. influenzae shuttle vector, lacZα, Cmr, p15a origin | 8, 37 |

| pTV05 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 2.6-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 (ORFs HI0937-HI0940) | This study |

| pTV10 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 4.0-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 (ORFs HI0364-HI0367) | This study |

| pTV15 | pTV10 with SPEC cassette cloned into SwaI site in HI0365 | This study |

| pTV16 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 1.4-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 as upstream flanking region of HI0366 | This study |

| pTV17 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 1.0-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 as downstream flanking region of HI0366 | This study |

| pTV18 | pUC18N containing the EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pTV16 and HindIII-BamHI fragment from pTV17 | This study |

| pTV19 | pTV18 with SPEC cassette cloned into the BamHI site to create a deletion of HI0366 | This study |

| pTV20 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 0.6-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 as upstream flanking region of HI1182 | This study |

| pTV21 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 0.5-kbp PCR product from Rd KW20 as downstream flanking region of HI1183 | This study |

| pTV22 | pUC18N containing the EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pTV20 and HindIII-BamHI fragment from pTV21 | This study |

| pTV23 | pTV22 with SPEC cassette cloned into BamHI site to create a deletion of HI1182/HI1183 (ligA) | This study |

| pTV24 | pTV05 with SPEC cassette cloned into SwaI site in HI0939 | This study |

| pTV29 | pCR2.1-TOPO carrying a 2.1-kbp fragment from Rd KW20 (CDS HI0365 and HI0366 and associated CRE site) | This study |

| pTV30 | Shuttle plasmid containing the HindIII-BamHI fragment from pTV29 cloned into the HindIII-BamHI site of pSU2718 | This study |

Antibiotic concentrations used for selection of E. coli: spectinomycin (Sp), 150 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 50 μg/ml; and ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg/ml.

Antibiotic concentrations used for selection of H. influenzae: spectinomycin (Sp), 200 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 2 μg/ml; and novobiocin (Nov), 2.5 μg/ml.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the Recombinant DNA/Protein Resource Facility at Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Computational analysis.

Partial annotation of incomplete genomic sequences was accomplished with Artemis 5 (50) and the BLAST algorithms (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (2, 20). The presence of export signal sequences was detected with SignalP 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-2.0/) (43). The likelihood of a signal peptide cleavage site in a particular protein was scored as a positive or negative for four different properties with the neural network model and as a secretory or nonsecretory protein with the Hidden-Markov model. Proteins scoring at least two positive results in the neural network model and identified as a probable secreted protein by the Hidden-Markov model method were classified as putative exported proteins for this study. All other DNA and protein sequence analyses were performed with the VectorNTI suite (version 8.0; Informax, Frederick, Md.).

Isolation of plasmid and chromosomal DNA.

Plasmids were purified from E. coli with the Wizard Plus miniprep kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Preparation of chromosomal DNA was accomplished with the DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) following the manufacturer's protocol for isolating DNA from gram-negative bacteria.

Transformation of plasmids.

Plasmid constructs were transferred into electrocompetent or chemically induced competent E. coli cells. Electrocompetent E. coli DH5α was produced by the method of Sharma and Schimke (53). Electroporation was performed with an Eppendorf 2510 electroporator at a setting of 17 kV/cm. Transformation with chemically competent cells was performed with commercially prepared E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) following the manufacturer's directions.

Plasmid constructs were transformed into H. influenzae by two methods. In the first method, cells were made competent by the MIV procedure, and plasmids were introduced by the method described by Poje and Redfield (44). In the second method, plasmids were introduced into H. influenzae strains by electroporation by the method of Mitchell et al. (40) with the following changes: cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4, and electroporation was performed at 14 kV/cm. Following the introduction of plasmids by either method, 2 ml of sBHI was added to the cells and the mixture was allowed to incubate for 2 h at 37°C to allow expression of the plasmid-borne antibiotic marker.

PCR protocol.

Each 50-μl reaction mixture was composed of 1× reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl [pH 8.3]), 25 pmol of each primer, 0.5 μg of template DNA, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (50 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.). Thirty cycles of PCR were performed (each cycle consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min/kbp of expected product), followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Gene expression during competence development.

The kinetics of competence induction in MIV medium and transcriptional analysis of potential CRE-controlled operons were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR). A 100-ml culture of H. influenzae Rd KW20 was grown in sBHI to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3. A control was obtained by removing a 1-ml sample and mixing the sample with 2 ml of RNAProtect (QIAGEN) to stabilize the RNA. The remainder of the culture was collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g, washed once, resuspended in 100 ml of prewarmed MIV medium, and then incubated with vigorous aeration at 37°C. One-milliliter samples for analysis of RNA profiles were taken at 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, and 160 min and mixed with 2 ml of RNAProtect. The samples were incubated for 10 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g to pellet the cells. The supernatant was aspirated, and the pellets were frozen at −20°C until they were processed. RNA from each sample was isolated with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) as directed by the manufacturer and resuspended in 30 μl of RNase-free water. Residual chromosomal DNA was removed by digestion with amplification grade DNase I (Invitrogen). The RNA samples were used to prepare cDNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 7 μl of template RNA, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 500 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 1× RT buffer, 80 mU of RNase inhibitor, a 2.5 μM concentration of random hexamers, and 25 U of MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The synthesis reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 10 min, followed by incubation at 48°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Prior to analysis, the cDNA was diluted by addition of 180 μl of RNase-free water. Q-PCR was utilized to examine transcription of 16S rRNA (normalizer), known competence-related genes (tfoX, comA, and rec-2), and possible competence-regulated genes identified in this study (HI0364, HI0366, HI0368, HI0937, HI0938, HI0939, HI0942, HI1181, and HI1182).

Q-PCR.

Gene-specific oligonucleotide primers were designed with Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Primers were tested to determine amplification specificity, efficiency, and linearity of amplification to RNA concentration as described by the manufacturer. A typical 25-μl reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 250 nM each primer, and 5 μl of cDNA sample. Quantification reactions for each gene at each time point were performed in triplicate and normalized to concurrently run 16S rRNA levels from the same sample. Relative quantification of gene expression was determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method of Livak and Schmittgen (34), where ΔΔCT = (CT, Target − CT, 16S)Time x − (CT, Target − CT, 16S)Control.

Directed mutagenesis of HI0365 and HI0939.

A 4,019-bp region of the H. influenzae Rd KW20 genome consisting of genes designated HI0364 to HI0367 was amplified by PCR with primers 0364CloneF and 0364CloneR (Table 2). The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to yield pTV10 and plated on LB agar containing ampicillin and X-Gal. Verification of the correct insert was performed by automated DNA sequencing. The EcoRV-excised spectinomycin cassette from pSPECR was successfully cloned into the unique SwaI site (located within HI0365) of pTV10 to yield pTV15. The presence of the correct construct was confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequence analysis. The mutant allele was transformed into H. influenzae Rd KW20 by the static aerobic transformation method (41). Following overnight growth, transformants were selected on sBHI containing spectinomycin. Chromosomal DNA from selected transformants was prepared, and the presence of the correct construct in the H. influenzae genome was confirmed by PCR size analysis with primers QPCR-0365-F and QPCR-0366-R2. An insertion into HI0939 was created in the same manner. A 2,614-bp region of the H. influenzae Rd KW20 genome, consisting of genes designated HI0937 to HI0940, was amplified by PCR with primers 0938CloneF and 0938CloneR and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to result in pTV05. The spectinomycin cassette from pSPECR was cloned into the unique SwaI site in pTV05 (located in HI0939) to create pTV23. Following transformation into Rd KW20, the presence of the correct insertion was verified by PCR analysis with primers QPCR-0939-F and 0938Clone-R.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences used in this study

| Primera | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| 1182-UP-A | GAATTCATCTTTGCCTGTCATC |

| 1183-UP-B | GGATCCCTAAGAATTTACGT |

| 1183-DN-A | GGATCCCCTATTTATAAATCTGAC |

| 1183-DN-B | AAGCTTCAACGTATTGCCAT |

| 1182-F | ATCTTACGTAAATTCTTAG |

| 1183-R | GTCAGATTTATAAATAGG |

| 0366-UP-A | GAATTCCGCTAGATTATGC |

| 0366-UP-B | GGATCCTTTTAATTGGGCAGGAAG |

| 0366-DN-A | GGATCCAAATCAAGTATTGGAC |

| 0366-DN-B | AAGCTTTGTAAGTGATGCGC |

| 0366-R | TTCGGCGAATTAAGTGCTAATTC |

| 0364CloneF | AAAGTCACTGTAGAACAGCCTGC |

| 0364CloneR | AATAGTTGGCTGAAAAGCTGAC |

| 0938CloneF | GATTAAATTCAGCACCTAAACAAGG |

| 0938CloneR | AAAGTGCGGTCGAAAATAGG |

| 0365-6F | CGCAAAAGAAGGACACAAAG |

| 0365-6R | CGGGATCCAATACTTGATTTGGC |

| QPCR-tfoX-F | GCTTTTGGCGAGGATTGGAT |

| QPCR-tfoX-R | TCAGCTAAAGCAACCGAAACC |

| QPCR-rec2-F | ACGCTTATCGCCACAGCAA |

| QPCR-rec2-R | AGGCACCTCTTTCGCTTTCC |

| QPCR-comA-F | GCACTTTACAAATCGGCATTCA |

| QPCR-comA-R | TGTGGCTGTTCGAGATCATCA |

| QPCR-0364-F2 | TCGAATTAAAGGCACTGGAACA |

| QPCR-0364-R2 | GGGCGGCATAGTTATCAGAATG |

| QPCR-H10365 | GGATTTAACGCGCCAACAA |

| QPCR-0366-F2 | GCGGTTATTTTCCCTTTCATTTT |

| QPCR-0366-R2 | GTTCCACACGCGCTTTAGC |

| QPCR-0368-F | CGTGCCGTTGTTGATTGTG |

| QPCR-0368-R | GGTTCGCCATATTTTTCTTGCA |

| QPCR-0937-F3 | GGATTATTGATCCGCTAGATGGTACT |

| QPCR-0937-R3 | CCCGACTTCAGTGCGATTTT |

| QPCR-0938-F | TTTGCAGTACCATTATGGAAAACC |

| QPCR-0938-R | TCTGCCCGAGCCTGAATTT |

| QPCR-0939-F | ACAAACGCAAAATCAACACATGT |

| QPCR-0939-R | GAAATCCTAATCGGCGAAGATCT |

| QPCR-0942-F | AAATTTCCTATGCCAGCCAGTTT |

| QPCR-0942-R | AAACGCCACATCATTGAATCTTT |

| QPCR-1181-F | GGCATTATTAATTTCGAATAGCTTCA |

| QPCR-1181-R | CGTTAATTCTTCTGCAAAATGCA |

| QPCR-1182-F | GGGTTGGGTAATGTCTGAAAAGTT |

| QPCR-1182-R | AATAAGCTGGCGGCGATAAA |

All custom primers used in this study were manufactured by QIAGEN (Operon), Valencia, Calif.

Directed mutagenesis of HI0366.

Directed deletion of HI0366 was performed by the method previously described by Morton et al. (42). A 1,384-bp region immediately upstream of HI0366 was amplified from the Rd KW20 genome by PCR with primers 0366-UP-A and 0366-DN-B and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create pTV16. A 934-bp region immediately downstream of HI0366 was amplified by PCR with primers 0366-DN-A and 0366-DN-B and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create pTV17. These primers were designed to include unique restriction sites to facilitate cloning and assembly of mutagenic contructs. The upstream and downstream regions were cloned into pUC18N and transformed into E. coli by electroporation, and an isolate containing a plasmid exhibiting a single band of appropriate size upon agarose gel electrophoresis was chosen and designated pTV18. The spectinomycin resistance cassette from pSPECR was inserted into pTV18 at the unique BamHI site engineered at the junction of the upstream and downstream fragments. The correct construct was verified by restriction digestion and automated DNA sequence analysis. The construct was transformed into H. influenzae Rd KW20 as described above and plated on sBHI containing spectinomycin. Resistant colonies were chosen, and an Rd KW20 mutant lacking HI0366 was verified by PCR size analysis with primers 0366-UP-A and 0366-DN-B and primers QPCR-0366-F2 and QPCR-0366-R2.

Directed mutagenesis of HI1182/HI1183 (ligA).

The open reading frames (ORFs) designated HI1182 and HI1183 in the Rd KW20 genome form a single ORF, containing a frameshift in the original sequence data, that encodes an ATP-dependent DNA ligase (LigA) (12). Deletion of HI1182/HI1183 was performed as described above for the deletion of HI0366. In short, a 629-bp region immediately upstream of the ligA gene was PCR amplified from Rd KW20 chromosomal DNA with primers 1182-UP-A and 1182-UP-B and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create pTV20. A 513-bp region downstream of ligA was PCR amplified from the Rd KW20 chromosome with primers 1183-DN-A and 1183-DN-B and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create pTV21. The upstream and downstream regions were subcloned into pUC18N to create pTV22. The spectinomycin cassette from pSPECR was cloned into the unique BamHI site engineered at the junction of the upstream and downstream fragments, resulting in pTV23. The deletion construct was transformed into H. influenzae Rd KW20 by the MIV technique and plated on sBHI containing spectinomycin. Resistant colonies were chosen, and an Rd KW20 mutant lacking HI1182/HI1183 was verified by PCR size analysis with primers 1182-UP-A and 1183-DN-B and primers 1182-F and 1183-R.

DNA binding and uptake analysis.

Radiolabeled DNA for use in assays testing the ability to bind and uptake transforming DNA was prepared by nick translation as described by Dougherty and Smith (16). To digest the 3′ termini of the DNA, 12 μg of MAP9 DNA (Novr [novobiocin resistant]) was incubated at 37°C for 25 min in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 15 U of T4 DNA polymerase (Fisher Bioreagents, Fairlawn, N.J.), 1× NEB Buffer 4 (20 mM Tris-acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol [pH 7.9]), and 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml. This was followed by the addition of dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP (final concentration of each, 100 μm) and 30 μCi of [α-32P]dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), and the reaction was incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Unincorporated label was removed from the chromosomal DNA by Sephadex G-50 column chromatography. The volume of labeled DNA mixture was adjusted to 500 μl with TE buffer (specific activity, 1.5 × 105 cpm/μg). Mutant and wild-type cultures (each, 5 ml) were made competent by incubation for 100 min in MIV medium as previously described. Prior to addition of radiolabeled DNA, 1 ml was removed to determine transformation frequency. Ten microliters of radiolabeled DNA (250 μg) was added to 1 ml of competent cells, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37°C with shaking. The samples were transferred to an ice bath and divided equally into two tubes to test DNA binding and DNA uptake. The sample for DNA binding was centrifuged and washed once with 1 ml of MIV medium and resuspended in 100 μl of MIV. The sample for DNA uptake was treated with 10 μg of DNase I for 5 min, followed by the addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 0.5 M. The cells were pelleted, washed once in MIV medium containing 0.5 M NaCl, and resuspended in 100 μl of MIV. The total cell-associated count (DNA binding proficiency) and the DNase I-resistant count (DNA uptake proficiency) were quantified with a Beckman LS 6000SC scintillation counter.

Determination of transformation frequency.

One milliliter of competent cells was incubated with 1 μg of MAP9 DNA for 15 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 1 μg of DNase I and further incubation for 5 min. Transformation efficiency was determined by the quantification method described by Jett et al. (31). Briefly, 10-μl samples from each dilution were plated in sextuplicate on square, gridded plates containing sBHI or sBHI-novobiocin. The use of novobiocin negates the need for an incubation period for development of antibiotic resistance. The frequency of transformation was determined by dividing the transformant colonies on the antibiotic plates by the viable count data from the control plates without selection. The effect of gene disruption on transformation efficiency was determined by dividing the transformation frequency of the mutant by the rate from a concurrently run Rd KW20 control. The benefit of adapting this quantification method to transformation studies is that more samples can be analyzed with far fewer plates than are required for increased statistical reliability, and the plating can be performed much faster than by traditional methods. The single downside is that the lowest transformation frequency that can be observed is 10−7. Comparison of this method to the standard protocol indicated that the transformation frequencies observed with both methods was equal for studied samples (data not shown).

Complementation of mutant strains.

To complement the transformation defect in the HI0366 mutant strain (HI1926), a plasmid was constructed that carried the HI0366 gene. A 2.1-kbp PCR product, encoding ORF HI0365 and HI0366 and associated CRE site, was amplified from Rd KW20 genomic DNA with primers 0365-6F and 0365-6R. The product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, as previously described, to create pTV29. This plasmid was digested with HindIII and BamHI, and the DNA band corresponding to the chromosomal insert was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and subcloned into HindIII-BamHI-digested pSU2718, a shuttle vector with a p15a origin of replication that allows establishment of the plasmid in H. influenzae. This construct was electroporated into E. coli DH5α, and a plasmid bearing the correct insertion was recovered and designated pTV30. This plasmid was electroporated into HI1926 to create the merodiploid strain HI1942. PCR analysis and antibiotic profiles confirmed that the original deletion was maintained in HI1942. The ability of wild-type strains Rd KW20, HI1926, and HI1942 to be transformed by MAP9 DNA to novobiocin resistance was compared by the MIV method of competence induction.

Similar methods were employed to attempt to complement the HI0939 insertion mutant. Plasmids were constructed bearing HI0938-HI0939 or HI0938-HI0941 and the associated CRE site in pSU2718. Neither MIV plasmid transformation nor electroporation was successful in establishing these plasmids in either Rd KW20 or the HI0939 mutant strain (HI1923).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the complete HI1182/HI1183 (ligA) gene has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AY662955.

RESULTS

Computer analysis of CRE regions.

Previous analysis of the Rd KW20 genomic sequence identified putative CRE sites upstream of ORFs HI0364 and HI1181 (32). It was assumed that these CREs were associated with HI0364 and HI1181 due to proximity between the CRE site and these ORFs. However, both CRE sites are located between divergently transcribed operons and could effect transformation in either direction. Additionally, MacFadyen identified a site upstream of HI0937 (suhB) in strain Rd KW20 that was categorized as a binding site for the cAMP-CRP complex (35), but this latter site displays an 85% match with the consensus CRE. Our BLAST analyses of the ORFs surrounding each of these sites indicated that the original assignments might be incorrect. The product of HI0366 showed significant homology to conserved hypothetical proteins annotated as putative fimbrial biogenesis and twitching motility proteins, suggesting that the protein is pilin related and therefore a possible competence factor. The designated subject for CRE0364 control, HI0364, encodes for a putative penicillin binding protein. While insertions in other penicillin binding proteins have been shown to have a negative effect on transformation in H. influenzae (16), presumably due to changes in cell wall structure, none of these genes have been demonstrated to be under the control of the competence regulon and none are associated with apparent CRE elements.

Examination of the ORFs that could be divergently transcribed from the putative CRE0937 also identified potential pilin-related genes. The products of the ORFs designated HI0938 to HI0941 share little homology to proteins outside of members of the Pasteurellaceae. However, characteristics of these four putative proteins are consistent with prepilin proteins: their mass is less than 20 kDa, they contain short N-terminal leader peptides with a hydrophobic stretch, and they display no sequence conservation in the C-terminal regions (10). In contrast, HI0937 shows significant homology (65% identity) to suhB from E. coli, a gene that encodes an inositol monophosphatase that also appears to participate in posttranscriptional control of gene expression (11).

Examination of the ORFs surrounding the putative CRE upstream of HI1181 indicates that HI1182/HI1183 is a candidate more likely to fall under the control of the competence regulon. HI1182/HI1183 encodes an ATP-dependent DNA ligase (LigA), whereas HI1181 encodes a phosphoheptose isomerase involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis (6, 12).

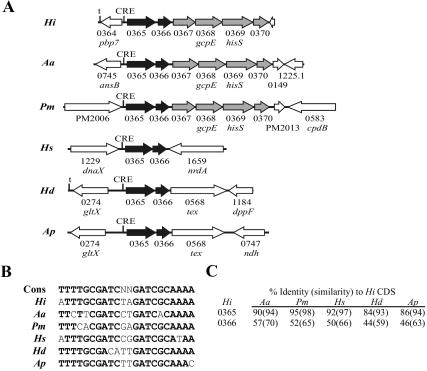

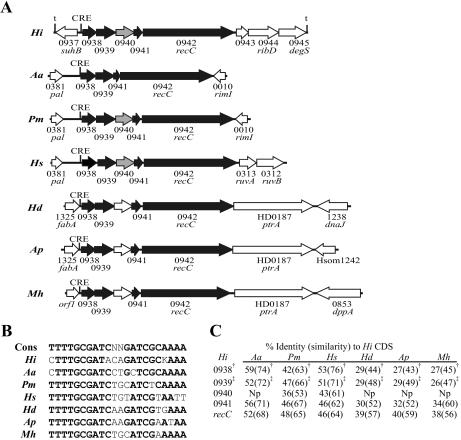

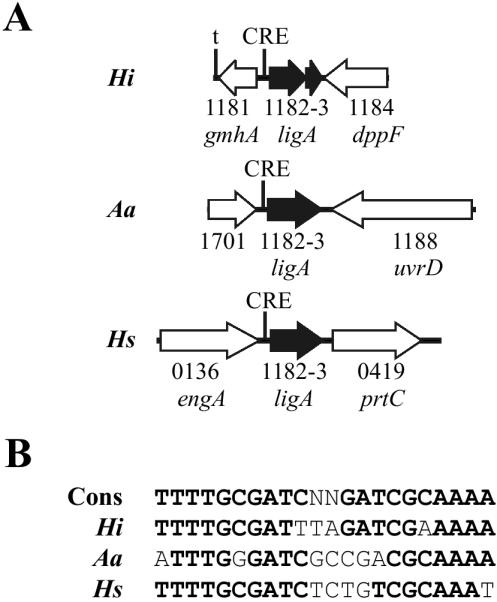

To gain further insight into the organization and potential regulon involvement of the ORFs contiguous with the three putative CRE sites discussed above, we analyzed homologous regions in the genomic sequences of the other members of the family Pasteurellaceae (Table 3). The sequence of the HI0365 and HI0366 homologs in Mannheimia haemolytica is incomplete and could not be analyzed. HI0365 and HI0366 homologs are present in the sequences from the other analyzed Pasteurellaceae and are associated with a putative CRE site immediately upstream (Fig. 2). In Haemophilus somnus, Haemophilus ducreyi, and M. haemolytica, the ORFs downstream of HI0366 in Rd KW20 are located elsewhere in the genome and do not have an associated CRE site. Only Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and M. haemolytica had HI0364 homologs, and these homologs do not have an associated CRE in either organism. The putative prepilin homologs HI0938 to HI0941 and recC were found as a unit with an associated CRE site in all the genomic sequences examined (Fig. 3). In contrast, the homolog of HI0937 in each of the organisms was located elsewhere in the genome and did not have an associated CRE in any of the family members. Besides Rd KW20, only A. actinomycetemcomitans and the H. somnus strains contained ligA (HI1182/HI1183) homologs, but a putative CRE site was located immediately upstream of the gene in these organisms (Fig. 4). HI1181 homologs existed in each of the family members but were not associated with an identifiable CRE site.

TABLE 3.

Pasteurellaceae member genomic sequences examined in this study

| Organism and status | Accession no. or progressa | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Completed | ||

| H. influenzae Rd KW20 | NC_000907 | http://www.tigr.org |

| H. ducreyi 35000HP | NC_002940 | http://www.microbial-pathogenesis.org |

| P. multocida PM70 | NC_002663 | http://www.cbc.umn.edu/ |

| In progress | ||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans HK1651 | Assembled | http://www.genome.ou.edu |

| A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 strain 4074 | 8.6× | http://www.micro-gen.ouhsc.edu |

| H. somnus 129PT | 10.7× | http://www.jgi.doe.gov |

| H. somnus 2336 | 8.2× | http://www.micro-gen.ouhsc.edu |

| M. haemolytica PHL213 | 8× | http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu |

Values indicate fold coverage of the genome at the time of the analysis. Assembled, sequence completed but no accession number available as yet.

FIG. 2.

Organization and conservation of the CRE0364 region in the family Pasteurellaceae. (A) The numbers shown correspond to the HI strain designation (e.g., HI0365) in the Rd KW20 annotation, unless otherwise indicated, and are based upon the closest homolog in the Rd KW20 sequence. Black arrows indicate genes whose location in reference to the CRE element is conserved across the family; gray arrows indicate genes with partial positional conservation; white arrows indicate genes whose association with the CRE element in Rd KW20 is not conserved in the family. (B) Comparison of the putative CRE sequences upstream of the HI0365 homolog in each organism compared to the consensus CRE sequence from Rd KW20 (Cons). Nucleotides in boldface share 100% identity with the conserved sequence. (C) Degree of similarity of genes homologous to HI0365 and HI0366 in the Pasteurellaceae. Abbreviations: Hi, H. influenzae Rd KW20; Aa, A. actinomycetemcomitans HK1651; Pm, Pasteurella multocida PM70; Hs, H. somnus strains 129PT and 2336; Hd, H. ducreyi 35000HP; Ap, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 strain 4074.

FIG. 3.

Organization and conservation of the CRE0937 region in the family Pasteurellaceae. (A) The numbers shown correspond to the HI strain designation in the Rd KW20 annotation unless otherwise indicated and are based upon the closest homolog in the Rd KW20 sequence. Black arrows indicate genes whose location in reference to the CRE element is conserved across the family. Gray arrows indicate genes with partial positional conservation. (B) Comparison of the putative CRE sequences upstream of HI0938 in each organism compared to the consensus CRE sequence from Rd KW20 (Cons). Nucleotides in boldface share 100% identity with the conserved sequence. (C) Degree of similarity of genes homologous to those of HI0938 to HI0942 in the Pasteurellaceae. † and ‡, PulG and PulJ domains, respectively, are present in the rpsblast database; Np, homolog not present or poor homology. See the legend to Fig. 2 for abbreviations used; Mh, M. haemolytica PHL213.

FIG. 4.

Organization and conservation of the CRE1181 region in the family Pasteurellaceae (A) Numbers shown correspond to the HI number in the Rd KW20 annotation unless otherwise indicated and are based upon the closest homolog in the Rd KW20 sequence. Black arrows indicate genes whose location in reference to the CRE element is conserved across the family. White arrows indicate genes whose association with the CRE element in Rd KW20 is not conserved. The A. actinomycetemcomitans and H. somnus LigA homologs demonstrated 69% identity (89% similarity) and 71% identity (85% similarity), respectively, to the Rd KW20 LigA sequence. (B) Comparison of the putative CRE sequences upstream of the ligA homolog in each organism compared to the consensus CRE sequence from Rd KW20 (Cons). Nucleotides in boldface share 100% identity with the conserved sequence. See the legend to Fig. 2 for definitions of the abbreviations used.

Q-PCR examination of gene expression during competence development.

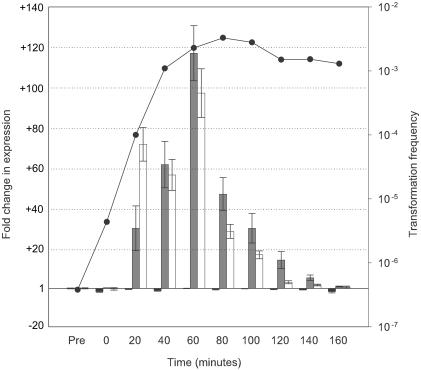

To determine if the pattern of putative CRE relationships identified in silico was biologically relevant, we examined the expression of a number of genes during the development of competence in MIV medium. Previous studies using β-galactosidase fusions demonstrated increased production of the fusion products from the CRE sites upstream of comA and rec-2 in response to competence development (26). Expression from tfoX fusions had been shown to increase during competence development (63). However, Bannister has shown that this effect appears to be mediated primarily by RNA secondary structure in the tfoX transcript (3). Our examination of the expression of comA and rec-2 by Q-PCR demonstrated that the expression of the two genes increased dramatically following transfer into MIV medium (Fig. 5). Maximal increases of 117-fold (±14) for rec-2 and 97-fold (±12) for comA were observed at 60 min into competence induction. Subsequently, expression of both genes declined to pretreatment levels at 160 min. In contrast, expression of tfoX remained relatively constant, with a maximum variation of 2.6-fold (±0.6) from pretreatment levels.

FIG. 5.

Expression profile of tfoX, rec-2, and comA during competence development. Q-PCR was employed to examine transcription of known competence genes during development of competence in MIV medium. Values represent the fold change in expression with respect to levels in the control (pretreated) sample as determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method (34). Error bars indicate the range in fold change as determined by this method. Black bars, tfoX; gray bars, rec-2; white bars, comA. CRE sites are present upstream of rec-2 and comA, and both have been shown to be dependent on tfoX for expression. The transformation frequency at each time point is indicated by the closed circles.

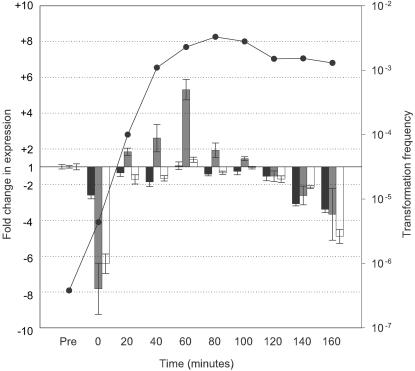

Examination of genes contiguous with CRE0364 (Fig. 6) showed that transcription of the three genes studied appeared to drop immediately upon centrifugation but recovered to near pretreatment levels at 20 min. Transcription of HI0364 (pbp-7) and HI0368 (gcpE) did not increase more than 1.1-fold (±0.2) and 1.4-fold (±0.15) over the control levels. However, expression of HI0366 reached a maximal increase of 5.3-fold (±0.6) at 60 min after transfer into MIV. The transcription levels of all three genes examined declined below pretreatment levels after 120 min in MIV. We also examined transcription of HI0365; it demonstrated the same magnitude of increase as HI0366 at 60 min, but transcript levels after 120 min fell below the linear range determined for the primers utilized (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Expression profiles of genes contiguous with CRE0364 during competence development. Q-PCR was employed to examine transcription of HI0364 (black bars), HI0366 (gray bars), and HI0368 (white bars) during competence development in MIV medium. Values represent the fold change in expression with respect to levels in the control (pretreated) sample as determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method (34). Error bars indicate the range in fold change as determined by this method. The transformation frequency at each time point is indicated by closed circles.

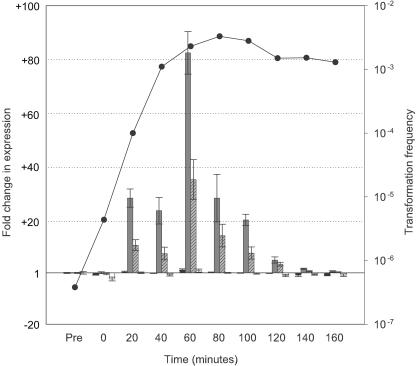

Examination of genes contiguous with CRE0937 (Fig. 7) showed a transcription profile similar to those of rec-2 and comA for HI0938 and HI0939. Maximal expression was observed at 60 min into induction with increases of 83-fold (±7.9) and 35-fold (±7.4), respectively. In contrast, expression of HI0937 (suhB) and HI0942 (recC) remained relatively steady-state and showed maximal increases of 2.1-fold (±0.4) and 1.8-fold (±0.6), respectively, following transfer into MIV.

FIG. 7.

Expression profiles of genes contiguous with CRE0937 during competence development. Q-PCR was employed to examine transcription of HI0937 (black bars), HI0938 (gray bars), HI0939 (hatched gray bars), and HI0942 (white bars) during competence development in MIV medium. Values represent the fold change in expression with respect to levels in the control (pretreated) sample as determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method (34). Error bars indicate the range in fold change as determined by this method. The transformation frequency at each time point is shown by closed circles.

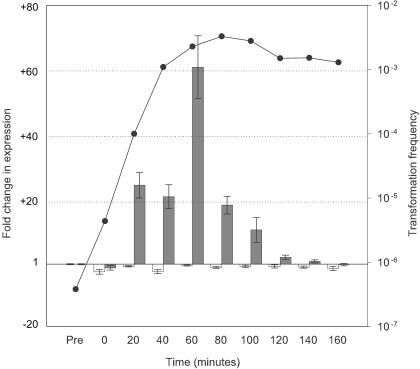

Finally, we examined expression of HI1181 (gmhA) and HI1182 (ligA), transcribed divergently from CRE1181 (Fig. 8). Transcription of ligA demonstrated a pattern similar to those of rec-2 and comA, showing a maximal 61-fold (±10) increase at 60 min after transfer into MIV. Transcription of gmhA decreased 3.3-fold (±0.7) upon transfer into MIV and remained below the pretreatment level in the remainder of the samples.

FIG. 8.

Expression profiles of genes contiguous with CRE1181 during competence development. Q-PCR was employed to examine transcription of HI1181 (white bars) and HI1182 (gray bars) during competence development in MIV medium. Values represent the fold change in expression with respect to levels in the control (pretreated) sample as determined by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method (34). Error bars indicate the range in fold change determined by this method. The transformation frequency at each time point is shown by closed circles.

Characterization of transformation phenotypes.

Our analysis of MIV-dependent transcription of genes contiguous to CRE0364, CRE0937, and CRE1181 indicated that several new genes may be members of the competence regulon. To determine the involvement of these genes in transformation, we created mutants in HI0365, HI0366, HI0939, and ligA. Transformation frequencies in MIV medium and DNA binding and uptake abilities of these mutant strains were compared to the those of the wild-type strain (Table 4). The HI0365 mutant strain HI1925 was as proficient as the wild type in both transformation to novobiocin resistance and uptake and binding of labeled MAP9 DNA. In contrast, the HI0366 mutant strain HI1926 was severely impaired in the ability to transform (<10−7 transformants/ml) and to uptake (0.3% of wild-type levels) DNA but demonstrated only a moderate decrease in DNA binding (28% of the wild type). The HI0939 mutant (strain HI1923) was also deficient in transformation (<10−7 transformants/ml), binding (1.1%), and uptake (0.08%). The ligA mutant (strain HI1924) demonstrated only a fivefold decrease in transformation frequency and near-wild-type levels of binding and uptake (84 and 92%, respectively).

TABLE 4.

Examination of transformation efficiency, DNA uptake and binding of wild-type and mutant H. influenzae Rd KW20

| Strain (medium) | Genotype | Transformation frequencya | DNA bindingb | DNA uptakeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rd KW20 (MIV) | Wild type | 1.0 × 10−3 | 100 | 100 |

| Rd KW20 (sBHI) | Wild type | <1.0 × 10−7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Rec-1 | rec-1 | <1.0 × 10−7 | 102.3 | 91.9 |

| HI1925 | HI0365::SPEC | 1.0 × 10−3 | 107.2 | 110.8 |

| HI1926 | ΔHI0366 | <1.0 × 10−7 | 28.3 | 0.3 |

| HI1923 | HI0939::SPEC | <1.0 × 10−7 | 1.1 | 0.08 |

| HI1924 | ΔHI1182/HI1183 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 84.2 | 94.0 |

Values are the number of novobiocin-resistant colony-forming units divided by total colony-forming units.

Values are the number of cell-associated counts per minute for each strain are divided by cell-associated counts for Rd KW20-MIV.

Complementation of the HI0366 mutant strain HI1926.

A plasmid (pTV30) was constructed containing the CDS HI0365, HI0366, and the associated CRE site in the H. influenzae shuttle vector pSU2718. The plasmid was established by electroporation in the HI0366 deletion mutant HI1926. To assess whether the plasmid bearing HI0366 was able to complement the chromosomal deletion of the gene, Rd KW20, HI1926(ΔHI0366) and HI1942(ΔHI0366, pTV30) were subjected to the MIV method of competence induction, and their abilities to be transformed to novobiocin resistance by MAP9 DNA were compared. The establishment of pTV30 in the HI0366 mutant strain fully complemented the deletion and restored transformation to wild-type levels. This confirms that the transformation defect in HI1926 was the result of the HI0366 deletion.

DISCUSSION

Three new members of the competence regulon in H. influenzae were identified in this study through a combination of in silico, transcriptional, and mutational analyses. Conserved CRE sites were located upstream of homologs of HI0365, HI0938, and HI1182/HI1183 in the Pasteurellaceae, and transcription of these genes increased in H. influenzae Rd KW20 in response to competence induction by transfer into MIV medium. Mutational analysis confirmed that the products of HI0366 and HI0939 are involved in transformation in Rd KW20.

The products of several of the genes shown in this study to be upregulated by competence induction exhibit similarities to proteins known to be involved with the type II secreton (T2S) and type IV pili (Tfp). Together, these are designated the PSTC proteins (for pilus, secretion, twitching motility, and competence) and have been shown to be integral parts of the transformation systems of most bacteria (17). While H. influenzae does not produce Tfp, PSTC homologs have been identified in this organism and have a demonstrable role in transformation (16, 56). A model has been suggested by Chen and Dubnau in which binding and uptake are mediated by a pseudopilus structure that utilizes components of the Tfp biogenesis machinery along with competence-specific pilin-like proteins (10).

The CRE site originally associated with HI0364 actually controls the transcription of HI0365 and HI0366. Comparative analysis of this operon in other members of the family Pasteurellaceae supports this conclusion. The magnitude of change in transcription of HI0366 was not as large as observed with either rec-2 or comA. This difference might reflect the finding that transcription of this operon is higher under noncompetence-inducing conditions than in other transformation-associated operons, since this operon appears to contain a gene unrelated to transformation. Mutational analysis demonstrates that the product of HI0366, but not HI0365, appears to be involved in transformation in Rd KW20. While it might be expected that the insertion in HI0365 would have polar effects on transcription of HI0366, the insertion we created had no discernible effect on transformation efficiency or DNA binding and uptake. Nevertheless, the HI0366 deletion mutant was severely impacted in the ability to transform and uptake DNA but remained proficient in DNA binding. The phenotype displayed by the HI0366 mutant strain resembles that exhibited by the com10 mutant described by Barouki and Smith (5). Since the defective gene in that mutant has not been identified, it is plausible that HI0366 may be the gene. The predicted product of HI0366 shares weak homology to PilF from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29% identity). Mutations in pilF in P. aeruginosa result in the lack of discernible pili, abolition of twitching motility, and the accumulation of processed PilA in the membrane fraction (59). This may indicate that PilF is necessary for export or assembly of pilin subunits. Since natural transformation has not been observed in this organism, it is impossible to assess a transformation phenotype in the P. aeruginosa pilF mutant. While the similarity of the product of HI0366 to PilF would suggest a similar role in H. influenzae in which it is involved in biogenesis of a transformation pseudopilus, the phenotype displayed by the HI0366 mutant is not consistent with this view. Mutations in other PSTC homologs in H. influenzae abolish both binding and uptake of DNA (16, 56), suggesting that an intact pseudopilus structure is necessary for both binding and uptake. Since the HI0366 mutant is proficient in binding DNA, it would suggest a direct role of the protein in transferring DNA across the outer membrane, but its exact function cannot be identified at this time. We propose naming HI0366 PilF2 to recognize the similarity to P. aeruginosa PilF but to avoid confusion with the unrelated pilin biogenesis protein PilF of Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Our findings also support the inclusion of HI0938 and HI0939 as members of the competence regulon in H. influenzae. Although transcription analysis of ORFs HI0940 and HI0941 was not performed, the similarity of their predicted products to prepilin-like proteins and lack of intergenic regions between the genes suggest that these genes are also members of this operon. While the association of recC with these genes is conserved throughout the examined members of the Pasteurellaceae, Q-PCR analysis does not support the inclusion of this gene within the regulon. While RecC may be involved in recombination of transforming DNA in H. influenzae, as has been demonstrated with N. gonorrhoeae (39), its vital role in other DNA metabolic activities would make it an unlikely candidate to be under tight control of competence development. Insertional mutagenesis of HI0939 demonstrates that its product, or that of the downstream genes, has a vital role in both uptake and binding of DNA. Unfortunately, complementation of the HI0939 mutant could not be performed, as plasmid constructs bearing HI0939 could not be established in either the wild-type or mutant strains. While the translated products of these genes lack blastp matches outside of the Pasteurellaceae, BLAST searches against the conserved domain database (rpsblast) identified matches of PulG for HI0938 and PulJ for HI0939. These proteins are type IV pseudopilins that form part of the T2S system for export of proteins from the periplasm in gram-negative bacteria (46, 47). The system is believed to be composed of a pseudopilus that is related to and shares components with the Tfp biogenesis machinery. It has been proposed that this structure resembles a piston and functions to propel targeted proteins across the outer membrane in a manner similar to twitching motility in the Tfp (30). In competence, this system could function either to export the DNA binding proteins to the cell surface or to facilitate the import of bound DNA through the outer membrane. The T2S has been best described for the secretion of pullulanase in Klebsiella oxytoca (46). The H. influenzae Rd KW20 genome contains homologs to several of the pullulanase operon genes, including pulD (HI0435 comE), pulE (HI0298 pilB), pulF (HI0297 pilC), pulG (HI0938), pulJ (HI0939), and pulO (HI0296 pilD). All of these genes appear to be transcribed from CRE-controlled operons, and mutations in all of these operons result in the abolition of DNA binding and uptake in H. influenzae, indicating the importance of the T2S to transformation (16, 26, 32, 56). We propose naming HI0938 PulG and HI0939 PulJ due to their domain matches to those proteins.

The results of Q-PCR examination of ligA expression during competence development and the presence of putative CRE sites upstream of ligA homologs in A. actinomycetemcomitans and the H. somnus strains support the inclusion of ligA in the competence regulon. An earlier attempt by Preston et al. to create a mutant in HI1182 was unsuccessful (45), leading to the conclusion that this gene might be essential. Our success in deleting ligA in this study argues against the indispensability of this gene for survival. While clearly upregulated in response to competence development in Rd KW20, ligA does not appear to be indispensable to transformation. The lack of HI1182/HI1183 homologs in many members of the Pasteurellaceae is consistent with a noncritical role in transformation. It is possible that the NAD+-dependent ligase (LigN) can substitute if LigA is absent. Interestingly, LigA appears to contain a signal peptide recognition sequence that would indicate a possible periplasmic location. We found LigA homologs in several other bacterial species, including Neisseria meningiditis and Vibrio cholerae, and these homologs also contain putative signal peptides. It is difficult to conceive a function for a DNA ligase as either an exported or a periplasmic protein for DNA metabolism or for transformation.

We also show that the three examined CRE sites located between divergently transcribed operons are responsible for control of transcription in a single direction. This may have important implications, as 8 of 10 of the predicted CRE sites in the Rd KW20 sequence are located between divergently transcribed operons. In particular, CRE0439 is located between two operons in which insertions or deletions of genes within each operon have deleterious effects on transformation. Further examination of transcription from CRE0439 and the other CRE sites will answer the question of whether bidirectional control by CREs occurs or whether their frequent location between divergent operons is merely coincidental. Additionally, we show that while CRE0364 is located closer to HI0364 than to HI0365, the element actually controls transcription of the HI0365 operon alone. Thus, the proximity of a promoter element to nearby genes can be an inaccurate predictor of regulatory targeting.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the ability of comparative genomics to identify competence operons. Characterization of the three newly identified operons by Q-PCR analysis indicated regulation consistent with that of other identified competence-regulated genes. Mutational analysis of HI0366 identified a novel transformation gene, pilF2, involved in uptake but not binding of DNA in H. influenzae. Mutational analysis of HI0939 identified a new gene, pulJ, that is possibly required for DNA binding and uptake in H. influenzae. The products of pulJ and HI0938 (pulG) are related to members of the type II secreton, confirming the importance of that system in transformation in H. influenzae.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI29611 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to T.L.S, D.J.M., and P.W.W.

We thank Larissa Madore for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, H., and G. Leidy. 1951. Determination of inherited traits of Haemophilus influenzae by desoxyribonucleic acid fractions isolated from type-specific cells. J. Exp. Med. 93:345-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bannister, L. A. 2000. An RNA secondary structure regulates sxy expression and competence development in Haemophilus influenzae. Ph.D. thesis. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

- 4.Barnhart, B. J., and S. H. Cox. 1968. Radiation-sensitive and radiation-resistant mutants of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 96:280-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barouki, R., and H. O. Smith. 1986. Initial steps in Haemophilus influenzae transformation. Donor DNA binding in the com10 mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 261:8617-8623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooke, J. S., and M. A. Valvano. 1996. Molecular cloning of the Haemophilus influenzae gmhA (lpcA) gene encoding a phosphoheptose isomerase required for lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3339-3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catlin, B. W., J. W. Bendler III, and S. H. Goodgal. 1972. The type b capsulation locus of Haemophilus influenzae: map location and size. J. Gen. Microbiol. 70:411-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler, M. S. 1991. New shuttle vectors for Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli: P15A-derived plasmids replicate in H. influenzae Rd. Plasmid 25:221-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandler, M. S. 1992. The gene encoding cAMP receptor protein is required for competence development in Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1626-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, I., and D. Dubnau. 2003. DNA transport during transformation. Front. Biosci. 8:s544-s556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, L., and M. F. Roberts. 2000. Overexpression, purification, and analysis of complementation behavior of E. coli SuhB protein: comparison with bacterial and archaeal inositol monophosphatases. Biochemistry 39:4145-4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng, C., and S. Shuman. 1997. Characterization of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase encoded by Haemophilus influenzae. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1369-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifton, S. W., D. McCarthy, and B. A. Roe. 1994. Sequence of the rec-2 locus of Haemophilus influenzae: homologies to comE-ORF3 of Bacillus subtilis and msbA of Escherichia coli. Gene 146:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dargis, M., P. Gourde, D. Beauchamp, B. Foiry, M. Jacques, and F. Malouin. 1992. Modification in penicillin-binding proteins during in vivo development of genetic competence of Haemophilus influenzae is associated with a rapid change in the physiological state of cells. Infect. Immun. 60:4024-4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorocicz, I. R., P. M. Williams, and R. J. Redfield. 1993. The Haemophilus influenzae adenylate cyclase gene: cloning, sequence, and essential role in competence. J. Bacteriol. 175:7142-7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty, B. A., and H. O. Smith. 1999. Identification of Haemophilus influenzae Rd transformation genes using cassette mutagenesis. Microbiology 145:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubnau, D. 1999. DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:217-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foxwell, A. R., J. M. Kyd, and A. W. Cripps. 1998. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:294-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gish, W., and D. J. States. 1993. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat. Genet. 3:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodgal, S. H., and R. M. Herriott. 1961. Studies on transformations of Hemophilus influenzae. I. Competence. J. Gen. Physiol. 44:1201-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gromkova, R., and S. Goodgal. 1979. Transformation by plasmid and chromosomal DNAs in Haemophilus parainfluenzae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 88:1428-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gromkova, R., P. Rowji, and H. Koornhof. 1989. Induction of competence in nonencapsulated and encapsulated strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Curr. Microbiol. 19:241-245. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gromkova, R. C., T. C. Mottalini, and M. G. Dove. 1998. Genetic transformation in Haemophilus parainfluenzae clinical isolates. Curr. Microbiol. 37:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwinn, M. L., R. Ramanathan, H. O. Smith, and J.-F. Tomb. 1998. A new transformation-deficient mutant of Haemophilus influenzae Rd with normal DNA uptake. J. Bacteriol. 180:746-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwinn, M. L., A. E. Stellwagen, N. L. Craig, J.-F. Tomb, and H. O. Smith. 1997. In vitro Tn7 mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae Rd and characterization of the role of atpA in transformation. J. Bacteriol. 179:7315-7320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herriott, R. M., E. M. Meyer, and M. Vogt. 1970. Defined nongrowth media for stage II development of competence in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 101:517-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herriott, R. M., E. Y. Meyer, M. Vogt, and M. Modan. 1970. Defined medium for growth of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 101:513-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiltke, T. J., A. T. Schiffmacher, A. J. Dagonese, S. Sethi, and T. F. Murphy. 2003. Horizontal transfer of the gene encoding outer membrane protein P2 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Infect. Dis. 188:114-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobbs, M., and J. S. Mattick. 1993. Common components in the assembly of type 4 fimbriae, DNA transfer systems, filamentous phage and protein-secretion apparatus: a general system for the formation of surface-associated protein complexes. Mol. Microbiol. 10:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jett, B. D., K. L. Hatter, M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1997. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. BioTechniques 23:648-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karudapuram, S., and G. J. Barcak. 1997. The Haemophilus influenzae dprABC genes constitute a competence-inducible operon that requires the product of the tfoX (sxy) gene for transcriptional activation. J. Bacteriol. 179:4815-4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karudapuram, S., X. Zhao, and G. J. Barcak. 1995. DNA sequence and characterization of Haemophilus influenzae dprA+, a gene required for chromosomal but not plasmid DNA transformation. J. Bacteriol. 177:3235-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacFadyen, L. P. 2000. Regulation of competence development in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Theor. Biol. 207:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacFadyen, L. P., D. Chen, H. C. Vo, D. Liao, R. Sinotte, and R. J. Redfield. 2001. Competence development by Haemophilus influenzae is regulated by the availability of nucleic acid precursors. Mol. Microbiol. 40:700-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez, E., B. Bartolome, and F. de la Cruz. 1988. pACYC184-derived cloning vectors containing the multiple cloning site and lacZ alpha reporter gene of pUC8/9 and pUC18/19 plasmids. Gene 68:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy, D. 1989. Cloning of the rec-2 locus of Haemophilus influenzae. Gene 75:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehr, I. J., and H. S. Seifert. 1998. Differential roles of homologous recombination pathways in Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin antigenic variation, DNA transformation and DNA repair. Mol. Microbiol. 30:697-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell, M. A., K. Skowronek, L. Kauc, and S. H. Goodgal. 1991. Electroporation of Haemophilus influenzae is effective for transformation of plasmid but not chromosomal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:3625-3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morton, D. J., L. O. Bakaletz, J. A. Jurcisek, T. M. VanWagoner, T. W. Seale, P. W. Whitby, and T. L. Stull. Reduced severity of middle ear infection caused by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lacking the hemoglobin/hemoglobin-haptoglobin binding proteins (Hgp) in a chinchilla model of otitis media. Microb. Pathog. 36:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Morton, D. J., P. W. Whitby, H. Jin, Z. Ren, and T. L. Stull. 1999. Effect of multiple mutations in the hemoglobin- and hemoglobin- haptoglobin-binding proteins, HgpA, HgpB, and HgpC, of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect. Immun. 67:2729-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. Von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poje, G., and R. J. Redfield. 2003. Transformation of Haemophilus influenzae. Methods Mol. Med. 71:57-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston, A., D. Maskell, A. Johnson, and E. R. Moxon. 1996. Altered lipopolysaccharide characteristic of the I69 phenotype in Haemophilus influenzae results from mutations in a novel gene, isn. J. Bacteriol. 178:396-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pugsley, A. P. 1993. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:50-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pugsley, A. P., O. Francetic, O. M. Possot, N. Sauvonnet, and K. R. Hardie. 1997. Recent progress and future directions in studies of the main terminal branch of the general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria—a review. Gene 192:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranhand, J. M., and H. C. Lichstein. 1969. Effect of selected antibiotics and other inhibitors on competence development in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 55:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redfield, R. J. 1991. sxy-1, a Haemophilus influenzae mutation causing greatly enhanced spontaneous competence. J. Bacteriol. 173:5612-5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M. A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sethi, S., and T. F. Murphy. 2001. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2000: a state-of-the-art review. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:336-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Setlow, J. K., M. E. Boling, K. L. Beattie, and R. F. Kimball. 1972. A complex of recombination and repair genes in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Mol. Biol. 68:361-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma, R. C., and R. T. Schimke. 1996. Preparation of electrocompetent E. coli using salt-free growth medium. BioTechniques 20:42-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer, H. T., and R. M. Herriott. 1965. Development of competence of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 90:911-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tartof, K. D., and C. A. Hobbs. 1988. New cloning vectors and techniques for easy and rapid restriction mapping. Gene 67:169-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomb, J. F., H. el-Hajj, and H. O. Smith. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of a cluster of genes involved in the transformation of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Gene 104:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turk, D. C. 1984. The pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Med. Microbiol. 18:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, Y., S. D. Goodman, R. J. Redfield, and C. Chen. 2002. Natural transformation and DNA uptake signal sequences in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Bacteriol. 184:3442-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watson, A. A., R. A. Alm, and J. S. Mattick. 1996. Identification of a gene, pilF, required for type 4 fimbrial biogenesis and twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 180:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitby, P. W., D. J. Morton, and T. L. Stull. 1998. Construction of antibiotic resistance cassettes with multiple paired restriction sites for insertional mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 158:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams, P. M., L. A. Bannister, and R. J. Redfield. 1994. The Haemophilus influenzae sxy-1 mutation is in a newly identified gene essential for competence. J. Bacteriol. 176:6789-6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wise, E. M., Jr., S. P. Alexander, and M. Powers. 1973. Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate as a regulator of bacterial transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70:471-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zulty, J. J., and G. J. Barcak. 1995. Identification of a DNA transformation gene required for com101A+ expression and supertransformer phenotype in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3616-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]