Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to prove that administrating L. reuteri probiotics can increase the level of BD-2 saliva and BD-2 expression in the epithelial parotid glands of Wistar rats.

Materials and Methods:

Experimental design in this study was randomized control group post test only. Twenty-four white male Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain rats were divided into four groups. The negative control group included rats not induced by S. mutans whereas the positive control group included rats induced by S. mutans. The two treatment groups are as follows: treatment 1 (T1), the group that is induced for 14 days by L. reuteri and 7 days by S. mutans and treatment 2 (T2), the group which is induced simultaneously by S. mutans and L. reuteri for 14 days. L. reuteri culture at a concentration of 108 colony-forming unit/ml and S. mutans culture at a concentration of 1010 are induced in the oral cavity of the Wistar rats. The Elisa technique is used to examine the salivary level of BD-2, whereas the immunohistochemical technique is used to examine the BD-2 expression in the epithelial salivary glands.

Results:

The study shows the increasing levels of BD-2 and BD-2 expression in the epithelial parotid glands after the administration of L. reuteri probiotics. Besides, there is a relationship between the increasing expression of BD-2 in the epithelial parotid glands with the decreasing amount of S. mutans.

Conclusion:

Giving L. reuteri probiotic scan increases the level of saliva of BD-2 and the expression of BD-2 in the parotid glands.

Keywords: Beta defensin-2, caries, Lactobacillus reuteri probiotics, Streptococcus mutans

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is a problem that is commonly found in the oral cavity, especially in children. The United States Surgeon General's publication in May 2000 described that dental caries is a chronic disease in childhood.[1] Based on the Basic Health Research (Riskesdas) in 2007 released by the Ministry of Health, 76% of children in East Java experienced dental caries, whereas in the Department of Health (Dinkes) of Surabaya, 4359 students among 61,214 students have oral cavities.[2,3]

Even though the prevention of dental caries has been done, there is no effective way to control it in children. Etiology of dental caries was very multifactorial. The etiology of dental caries was multifactorial. There are three main factors that cause dental caries, carbohydrate diet (especially sucrose), Streptococcus mutans infection, and specific response from the host (innate immunity).[4] Innate immunity in the oral cavity is the part of immune system that serves as a front-line defense against pathogens. One of the innate immunities that has an important contribution to keep the body balance is antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). AMP that was first identified in oral cavity epithelium is beta defensins (BDs). These peptides have a wide range of antimicrobial activity capable of against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as against fungi and viruses.[5]

One of the caries prevention approaches that has been focused on recently is probiotics consumption. According to the WHO, probiotics are living microorganisms which will give benefits for health when consumed in sufficient amount.[6] Probiotics are commensal bacteria, and it is an excellent inducer for BD-2 in oral cavity epithelial cells.[7] The aims of this research were to determine the effects of Lactobacillus reuteri probiotics induction on BD-2 level on saliva and its expression in parotid gland epithelial cells to reduce S. mutans as the cause of dental caries.

MATERIALS AND METODS

Research design and animal model

Ethical clearance of this research was obtained from the Commission of Ethical Feasibility of Health Research, Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Airlangga. Experimental design in this study was randomized control group post test only. Wistar Rats are used as animal models in caries research.[8] Twenty-four male white rats (Rattus norvegicus Wistar strain) were divided into four groups: Negative control group, positive control group, treatment group 1 (T1), and treatment group 2 (T2). Negative control group was not induced either with S. mutans or L. reuteri and positive control group was induced with S. mutans for 14 days. T1 was induced with L. reuteri for 14 days and S. mutans for 7 days, whereas T2 was induced with S. mutans and L. reuteri simultaneously for 14 days. The analysis unit in this study was saliva and parotid gland epithelial cells tissue. L. reuteri concentration that has been used as inducer was 4 × 108 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml[9] while the concentration of S. mutans was 1010 CFU/ml.[10] On the 15th day, rats' saliva was taken before they were dissected. Rats' saliva production was stimulated by the administration of 1 cc of ketamine HCl (100 mg/cc) and 1 cc of diazepam (Sutezolid) (5 mg/cc) that were injected intramuscularly through the thigh.[11] Saliva was taken with micropipette after 2–3 of stimulation and then placed into Eppendorf column for about 100 μl. Centrifugation was done at 6000 rpm for 10 min at 40°C, and supernatants were collected with micropipette and then stored at −80°C–800°C of temperature for Elisa preparation.

Elisa procedures were then conducted based on manual kit RnD system. Then, 20 μl of saliva samples were added with 80 μl blocking buffer (0.20% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA), put into microplate polycarbonate previously been coated with Ab capturing of anti BD-2 rat monoclonal antibody (Santa-Cruz), and then incubated at 4°C for 24 h. After that, it was washed three times with wash solution (0.15 M NaCl + 0.05% Triton X-100 + 0.02 g NaN3 in 1 L of distilled water). Next, it was added with Ab detection (secondary Ab) labeled with biotin and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. It was then washed three times with wash solution. Afterward, each well was added with 100 μl of Ab detection (anti-BD-2) labeled with horseradish peroxidase and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. It was then washed three times with wash solution. Next, it was added with 50 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate, then incubated at room temperature for 40 min, and stopped by adding 1 N H2 SO4. The results of optical density were read by using microplate reader (Bio-Rad Model 680) at 450 nm wavelength.

The parotid glands were taken out and prepared on paraffin blocks for immunohistochemistry. ANOVA/SPSS (Developed by IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) test was conducted to determine the differences between BD-2 saliva level and BD-2 expression in parotid gland epithelial cells among the groups.

The preparation of Lactobacillus reuteri suspension

L. reuteri ProDentis starter contained in tablet x (DSM 17938 + ATCC PTA 5289) was cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C anaerobically in the gas-generating kit (Oxoid). Bacteria cell mass will appear as white sediment in the tube. Bacteria were then cultured into MRS medium agar (DeMan-Rogosa-Sharpe; Merck GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) by streak method and incubated for 2 × 24 h at 37°C. Bacterial single-cell colony was taken and reincubated into BHI medium for 24 h at 37°C to obtain OD = 108 cfu/ml (λ = 625) nm.[12]

The preparation of Streptococcus mutans suspension

S. mutans serotype c was cultured from freeze-dried stock. Bacterial colony was taken with inoculating loop, cultured into BHI broth, and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The cultured bacteria were streaked into blood agar medium and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Bacterial single-cell colony was taken and reincubated into BHI medium for 24 h at 37°C to obtain OD = 1010 cfu/ml (λ = 625) nm.[12]

Examination of beta defensin-2 expressions

Observation of BD-2 expression using immunohistochemistry and immunohistochemical staining was done based on previous research.[13,14]

RESULTS

Beta defensin-2 levels in rats' saliva

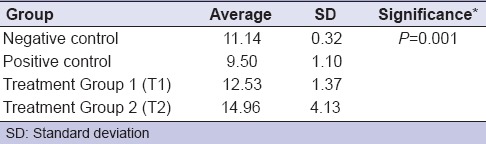

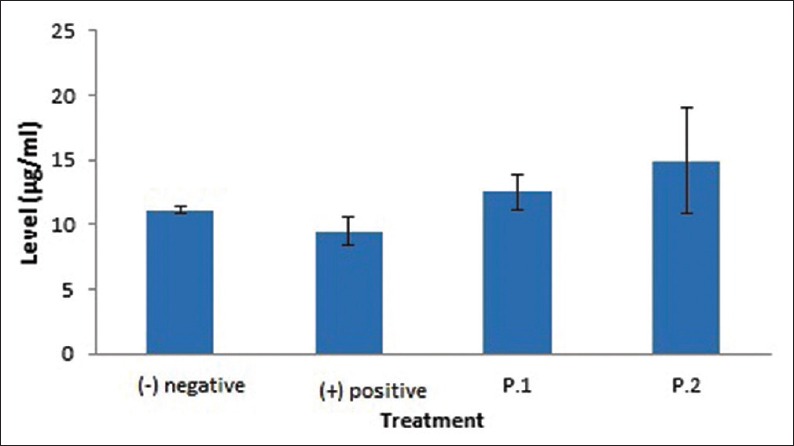

Elisa test was conducted to determine the levels of BD-2 in saliva after L. reuteri probiotics induction [Table 1]. The levels of BD-2 in the Wistar rats saliva among the treatment groups are significantly different (P = 0.00). BD-2 level in saliva of positive control group (induced by S. mutans) decreased compared to negative control group (11.14–9.50). Otherwise, BD-2 level in the saliva of the second group (T2) (induced with L. reuteri and S. mutans for 14 days) increased compared to T1 (12.53–14.96) [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Beta defensin-2 levels in saliva of Wistar rats in each treatment group

Figure 1.

Mean values and standard deviations of beta defensin-2 levels in the saliva of Wistar rats after being induced with Lactobacillus reuteri probiotics in each treatment group

Beta defensin-2 expression in parotid gland epithelial cells

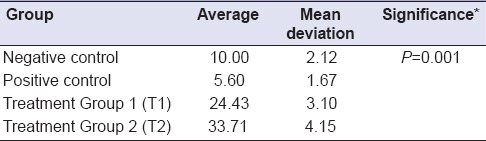

The examination was conducted through immunohistochemistry method. The distribution of BD-2-expressing cells in parotid gland cells in each group after L. reuteri probiotics induction is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Beta defensin-2 expression in parotid gland epithelial cells

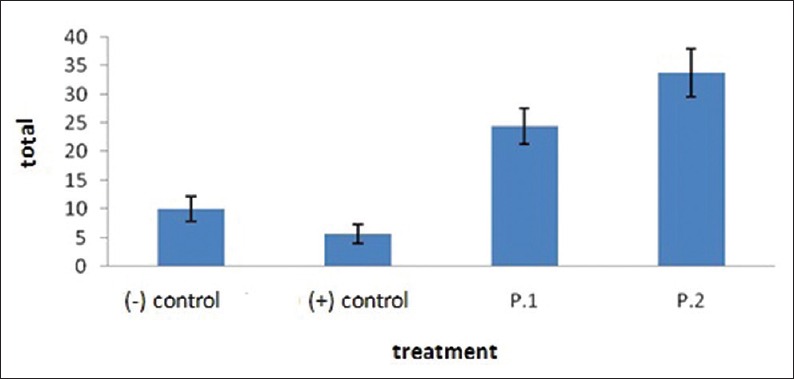

BD-2 expression in parotid gland epithelial cells was significantly different among the treatment groups (P = 0.001). Average BD-2 expression of negative control group decreased compared to positive control group (10.00–5.60) whereas this expression in T2 increased when compared to T1 (24.43–33.71) [Figure 1].

DISCUSSION

BDs play an important role in the oral cavity; they are the first defense against bacterial infection. BDs consist of AMPs in the form of small cations. There are three BDs; BD-1, BD-2, and BD-3. They can be detected in salivary glands, gingival, tongue, and buccal mucosa. BDs have a bactericidal activity that can damage bacterial cell membranes. Expressions of BD-2 and BD-3 in oral mucosal epithelial cells are influenced by the existence of bacterial components or inflammatory mediators. Two main species of bacteria that cause dental caries are S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus, which are sensitive to BD-2.[15] Induction of L. reuteri into oral cavity increased the expression of BD-2. It reduces the number of S. mutans bacterial population related to dental caries.

BDs expression in salivary glands is a defense mechanism in the oral cavity against infection. BD-2 is a potent antimicrobial peptide effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria, including Gram–positive bacteria, Gram–negative bacteria and fungi. S. mutans, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and Porphyromonas gingivalis are bacteria sensitive to BD-2 and are the members of periodontal bacteria.[16]

The average concentration of defensins in epithelial cells reached 10–100 μg/ml. Peptides' distribution was not equal, so the local concentrations become higher.[17] Table 1 shows that the lowest concentration of BD-2 saliva was in the positive control group. The host will utilize BD-2 against S. mutans as the cause of caries infection. The average BD-2 level examined with Elisa of the positive control group was 9.50 μg/ml. This is the lowest concentration needed for activation. This is the lowest concentration needed for activaton, because defensin will be active on 1-10 μg/ml.[18] Almost all BDs in the oral cavity are expressed by keratinocytes inside the mouth and ductal cells of salivary glands. It supports this study results as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 which indicate that the highest expression of BD-2 occurred in Group 2. The highest levels of BD-2 also occurred in Group 2 [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Most of the proteins in saliva are produced by salivary gland acini cells. BD secreted from salivary ducts may attack bacteria, viruses, and fungi locally.[19]

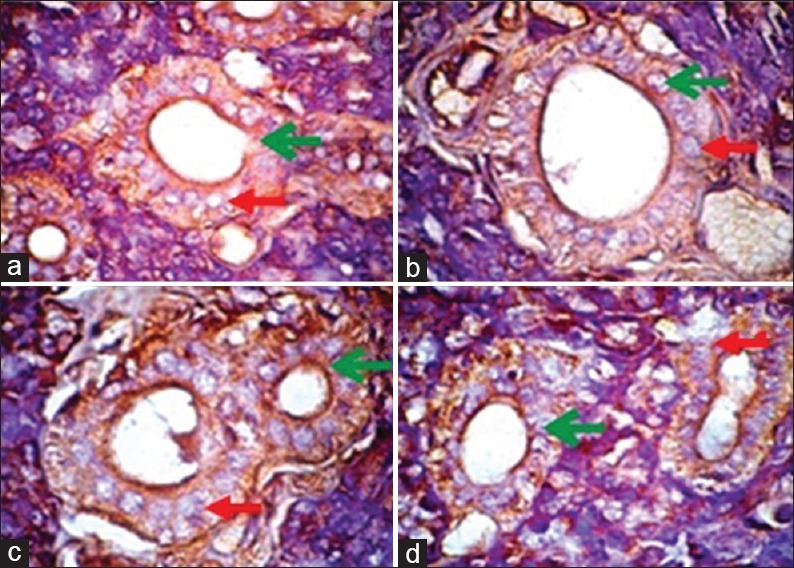

Figure 2.

The mean and standard deviations of number of cells of beta defensin-2 expression in the epithelial parotid glands after each group is being induced by Lactobacillus reuteri probiotics

This study proved that L. reuteri administration can increase BD-2 expression in epithelial parotid gland [Table 2 and Figure 2]. Parotid gland epithelial cells protect the host not only by providing a physical barrier but also through innate immune responses in the form of antimicrobial peptides.

Table 2 and Figure 2 show that the number of BD-2 expressions in positive control groups is the lowest compared to the other groups. The positive control group is the only group that was induced with S. mutans. It can be explained that S. mutans was not able to induce BD-2 expression in parotid gland epithelial cells. The research conducted by Schlee et al. showed that Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 strain can induce BD-2 expression, while the other forty E. coli isolates cannot induce it. Isolation and purification results of flagellin protein in E. coli Nissle 1917 were able to induce BD-2 expressions, while flagellin-deficient mutants of these bacteria were not able to induce defensins. Flagellin is an MAMP-determining factor in E. coli Nissle 1917 probiotic which can remarkably stimulate BD-2 expression.[20]

The induction of L. reuteri probiotics for 14 days with a concentration of 4 × 108 CFU/ml can increase the expression of BD-2 significantly (P = 0.001) [Table 2 and Figures 2, 3]. It indicates that BD-2 expression in epithelial cells of the parotid gland in Group 2 (T2) shows the highest BD-2 expression compared to the other groups. This can be expected that active molecules on L. reuteri cell wall and peptidoglycan will activate NOD-2 receptors in the cytoplasm. The signaling activation through Nod2 pathway involves RICK adapter proteins. The signaling activation through Nod2 pathway involves RICK adapter protein and will be activated to phosphorylate IKK complex. Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) in inactive form will bound to IκBa protein inhibitor in the cytoplasm. The stimuli will induce phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of IκB proteins which will lead to NF-κB translocation into the nucleus cores, and then NF-κB becomes active. The stimuli will induce phosphorylation, ubiquitination and degradation of IKB protein which will lead to NF-kB translocation into the nucleus cores, and then NF-kB becomes active to stimulate the target genes.[21]

Figure 3.

Results of immunohistochemical examination showing beta defensin-2 expression in the epithelial parotid gland in each group magnified (×1000). Green arrow showing cells expressing beta defensin-2. Red arrow showing cells that do not express beta defensin-2. Description: (a) Negative control, (b) positive control, (c) treatment Group 1 (P. 1), (d) treatment Group 2 (P. 2)

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that the induction of L. reuteri probiotics can increase BD-2 level in saliva and its expression in parotid gland epithelial cells.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge with gratitude to the support of Airlangga University Rector for research funding managed by Community Research and Service Institute, Airlangga University, as an Excellent Research Institution of Higher Education No. 965/UN3/2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shifa S, Muthu MS, Amarlal D, Rathna Prabhu V. Quantitative assessment of IgA levels in the unstimulated whole saliva of caries-free and caries-active children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2008;26:158–61. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.44031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Report. Basic Health Research. Jakarta: Research and Development Agency, Ministry of Health of Indonesian Republic; 2007. p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basic Health Research of East Java Province. Jakarta: Research and Development Agency, Ministry of Health of Indonesian Republic; 2007. p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tao R, Richard J, Jurevic, Kimberly K, Coulton Salivary antimicrobial peptide expression and dental caries experience in children. Ant Agent and Chem. 2005;49:3883–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3883-3888.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale BA, Fredericks LP. Antimicrobial peptides in the oral environment: Expression and function in health and disease. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2005;7:119–33. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale BA, Tao R, Kimball JR, Jurevic RJ. Oral antimicrobial peptides and biological control of caries. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl 1):S13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace TC, Guarner F, Madsen K, Cabana MD, Gibson G, Hentges E, et al. Human gut microbita and its relationship to health and disease. Nutrition Reviews Vol. 2011;69:392–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamont RJ, Burne RA, Lantz MS, Leblanc DJ. The Oral Environment-Oral Microbiology and The Immune response. American Society for Microbiology Press; 2006. pp. 201–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valeur N, Engel P, Carbajal N, Connolly E, Ladefoged K. Colonization and immunomodulation by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1176–81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1176-1181.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ooshima T, Sumi N, Izumitani A, Sobue S. Effect of inoculum size and frequency on the establishment of Streptococcus mutans in the oral cavities of experimental animals. J Dent Res. 1988;67:964–8. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670061501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gresz V, Tae-Hwan K, Hong G, Agre P, Steward MC, King LS, et al. Immunolocalization of AQP-5 in Rat Parotid and Submandibular Salivary Glands After Stimulation of Secretion in vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointes Liver Physiol. 2004;287:151–G161. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00480.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton S. Measurement of microbial cells by optical density. J Validation Technol. 2011;17:46–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soini Y, Pääkkö P, Lehto VP. Histopathological evaluation of apoptosis in cancer. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1041–53. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pizem J, Cor A. Detection of apoptosis cells in tumour paraffin sections. Radiol Oncol. 2003;37:225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura E, Eto A, Kato M, Hashizume S, Imai S, Nisizawa T, et al. Oral streptococci exhibit diverse susceptibility to human beta-defensin-2: Antimicrobial effects of hBD-2 on oral streptococci. Curr Microbiol. 2004;48:85–7. doi: 10.1007/s00284-003-4108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin C, Dang HN, Gazor F, Huang GT. Mouse salivary glands and human β-defensin-2 as a study model for antimicrobial gene therapy: Technical considerations. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28:352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz T. Defensins: Antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh D, Porter E, Shen B, Lee SK, Wilk D, Drazba J, et al. Paneth cell trypsin is the processing enzyme for human defensin-5. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:583–90. doi: 10.1038/ni797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abiko Y, Nishimura M, Kaku T. Defensins in saliva and the salivary glands. Med Electron Microsc. 2003;36:247–52. doi: 10.1007/s00795-003-0225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, Oelschlaeger TA, Stange EF, Fellermann K. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01563-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uehara A, Takada H. Synergism between TLRs and NOD1/2 in oral epithelial cells. J Dent Res. 2008;87:682–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]