Abstract

Tooth wear is a process that is usually a result of tooth to tooth and/or tooth and restoration contact. The process of wear essentially becomes accelerated by the introduction of restorations inside the oral cavity, especially in case of opposing ceramic restorations. The newest materials have vastly contributed toward the interest in esthetic dental restorations and have been extensively studied in laboratories. However, despite the recent technological advancements, there has not been a valid in vivo method of evaluation involving clinical wear caused due to ceramics upon restored teeth and natural dentition. The aim of this paper is to review the latest advancements in all-ceramic materials, and their effect on the wear of opposing dentition. The descriptive review has been written after a thorough MEDLINE/PubMed search by the authors. It is imperative that clinicians are aware of recent advancements and that they should always consider the type of ceramic restorative materials used to maintain a stable occlusal relation. The ceramic restorations should be adequately finished and polished after the chair-side adjustment process of occlusal surfaces.

Keywords: All-ceramic materials, all-ceramic restorations, surface roughness, tooth wear

INTRODUCTION

In many individuals, tooth wear is a natural unavoidable process that is usually a result of tooth to tooth and/or tooth and restoration contact. Contact usually occurs when sliding movements are taking place. The process of wear essentially becomes accelerated by the introduction of restorations inside the oral cavity,[1,2] and the rate of tooth surface loss is greater in case of opposing ceramic restorations.[3] Wear of the entire dentition is possible without the presence of any restoration, and it should always be aimed for the hardness of restorative materials and their wear behavior remains similar to that of natural enamel; otherwise, tooth surface loss [Figure 1] may lead to a variety of clinical problems including damage to the opposing enamel structure, loss of occlusal vertical dimension, problems in mastication, temporomandibular joint problems, hypersensitivity, and esthetic impairment.[4,5,6]

Figure 1.

Tooth surface loss in anterior maxilla

Based on the morphological and etiological factors, tooth wear can be classified into various types (erosion, attrition, abrasion, and abfraction).[7,8] Shellis and Addy[2] stated that tooth wear occurs due to interaction between erosion, attrition, and abrasion, whereas abfraction may potentiate the process. These mechanisms rarely act alone and always interact with each other, and this interface seems to be the major factor in occlusal and cervical wear.[9,10,11]

For many decades, ceramics have been used for esthetic restorations because of their excellent esthetic qualities and superior biocompatibility.[12] However, ceramics are brittle in nature, require careful polishing techniques and are abrasive to the opposite dentition.[13,14,15,16] There have been suggestions by authors that placement of ceramics over the occlusal surfaces should be avoided so that opposing dentition wear could be minimized.[17] For that reason, modified ceramics have been developed recently in an attempt to decrease their wear characteristics.

The newest materials have vastly contributed toward the interest in esthetic dental restorations.[17] The effects of newly introduced dental ceramics have been extensively studied in laboratories. However, laboratory studies which test the abrasion resistance could produce results that are completely different for the same materials tested in clinical studies. Despite the recent technological advancements, there has not been a valid in vivo method of evaluation involving clinical wear caused due to ceramics upon restored teeth and natural dentition.

THE RECENT ADVANCEMENTS IN CERAMICS

All-ceramic materials have superior esthetic qualities, and their appearance is very similar to natural dentition. Their brittleness is a major drawback as they tend to fracture in conditions where there are high tensile stresses. Advancements have been made to re-enforce these materials with crystalline materials.[18] The complete classification ceramics used in dentistry are outlined in Table 1.[19] A brief description of these materials is described below.

Table 1.

“Classification of All-Ceramic Material Types According to the Processing Technique”[21]

Sintered ceramics

Sintering is a process in which heat at very high temperatures is used to cause consolidation of the ceramic particles. Sintering causes a decrease in surface porosity and the bulk of ceramic during production, and the amount of porosities is directly influenced by the sintering time and temperature.[20] Porosities on the surface cause an increase in surface roughness of a ceramics and could lead to increase wear of opposing dentition.[14,20,21,22,23]

Porcelain can also be reinforced using alumina and magnesia,[24] it can be re-enforced into dental ceramics by a mechanism termed as “dispersion strengthening.”[25,26,27,28] Zirconia can be re-enforced into conventional feldspathic porcelain to achieve highest levels of strength. This mechanism of incorporating zirconia is termed as “transformation toughening.”[29,30] Zirconia stabilized with yttria has high fracture toughness, strength, and thermal shock resistance. It has decreased translucency and low fusion temperature.[31,32] Majority of zirconia re-enforced ceramics are radio-opaque, and copings are required to be veneered for better esthetic outcomes.

Glass ceramics

Restorations using glass ceramic materials are produced in a noncrystalline state which is converted into a crystalline phase by the process termed as devitrification.[33] Fabrication of restorations using glass ceramics involves the use of wax patterns made using the phosphate-bonded investment material. The burn-out process is done, and a centrifugal machine is used to cast the molten ceramic into the pattern at 1380°C. After the sprue is removed, glass is invested yet again and heated at 1075°C for a period of 6 h which leads to crystallization of glass to form “tetra-silicic fluoromica crystals.” The procedure of crystal growth and nucleation is termed as ceramming.[34,35] These crystals lead to increase in strength, abrasion resistance, fracture toughness, and chemical durability of the material.

Pressable ceramics

These ceramics involve the process of production at elevated temperatures in which sintering of the ceramic body occurs. The technique of fabrication prevents the formation of porosities and secondary crystallization which results in a restoration with superior mechanical properties.[36,37,38,39]

Until recently, Ivoclar Vivadent developed two more ceramics named as IPS e.max-Press and IPS e.max. IPS e.max-Press is processed in the laboratory with pressing equipment which provides very high accuracy of the restoration fit. The microstructure of this material can be distinguished as needle-like disilicate crystals which are embedded into a glass matrix. The flexure strength of IPS e.max-Press is more as compared to IPS Empress.[40]

Machined ceramics

The development of computer-aided design and computer-aided machining method for the fabrication of inlays, onlays, crowns, and bridges has lead us to the development of next generation of machinable ceramic material.[41,42,43,44] The crowns fabricated using these systems can be delivered to the patient in a single appointment since these are made chair-side. There are several drawbacks which include the expense of the equipment used, and also the process requires a high level of expertise.[45] If a zirconia coping is to be used, the color difference between the core of zirconia and adjacent tooth must be matched using a specific layering technique for the veneering ceramic, and appropriate shade selection technique should be practiced.[45,46,47]

CERAMICS AND TOOTH WEAR

Porcelain restorations, whether polished or not, have significant effects on opposing enamel or an opposing tooth with a restoration.[48] This is mainly due to their hardness and due to this fact; ceramic restorations are not the material of choice for anterior and posterior teeth on many occasions.[49] If the surface of a ceramic restoration is rough, there is a very high probability that it will cause excessive wear of the opposing restoration or the natural tooth.[50] When a ceramic restoration is fabricated in the dental laboratory [Figure 2], it must be polished using a specific sequence as per manufacturer's recommendation so that its surface roughness can be reduced. The restorations after laboratory polishing are subjected to glazing which produces a final smooth, hygienic surface.[20] If left unpolished and unglazed, there is a higher risk of plaque accumulation around the restoration and excessive wear of opposing dentition.[14]

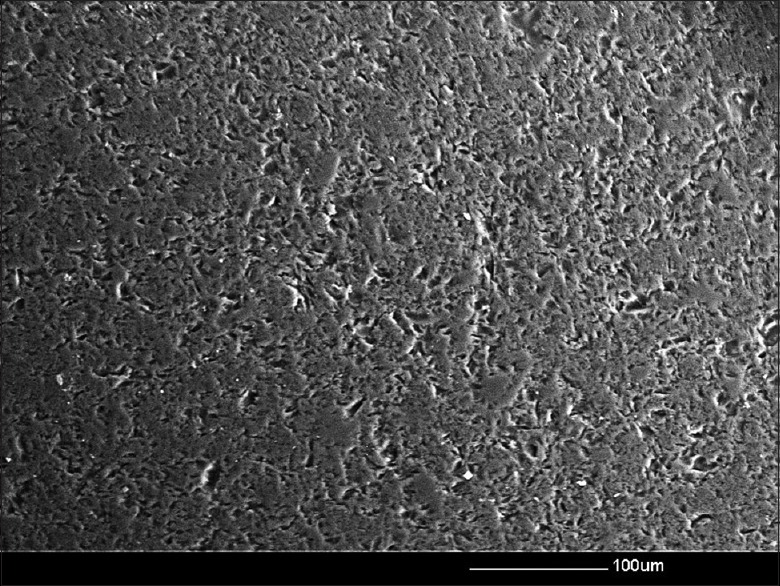

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscope image of an unglazed, unpolished ceramic surface

Jagger and Harrison[51] tested enamel wear caused by different ceramic surfaces and they came to a conclusion that there was no difference in the rate of enamel wear produced by a glazed and an unglazed surface, and it was similar and stated that the phenomenon of wear occurs by a combination of different factors which include abrasion, corrosion, adhesion, and fatigue.[1,52]

The notion that low-fusing porcelains produce lesser wear as compared to high-fusing porcelain is still debatable. Low-fusing porcelains offer a clinical advantage as their properties are much closer to that of human enamel.[53] Metzler et al.[54] investigated the effects of two low-fusing feldspathic ceramics and a traditional feldspathic ceramic on the loss of human enamel. Their results suggested that low-fusing feldspathic porcelains caused similar wear as compared to the traditional feldspathic porcelain, for all the measured periods.[55]

Porosity formation and increased the surface roughness of a ceramic [Figure 3] lead to reduce strength, poor appearance, and increased plaque accumulation.[56] The subsequent ceramic surface porosity may be exposed during wear process, and a sharp edge of the defect will be even more damaging for opposing dentition.[57,58] Higher sintering time, longer sintering temperature cycles, and particle size are three parameters which are associated with the porosity formation over ceramic surfaces.[59,60,61] Piddock[61] and Cheung and Darvell[56] stated that by increasing the sintering time, air entrapment occurs, and this leads to increased surface and subsurface porosities, and during laboratory fabrication process of ceramic crowns, the influence of mechanical vibration during manipulation of porcelain in layers has limited or no effect on the formation of porosities.[56,61]

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscope image of an abraded/adjusted ceramic surface

Dental porcelain is not only wear resistant but also exceedingly hard and abrasive against opposing dentition.[62] Porcelain is more abrasive than gold, amalgam, and composite restorative material and this is why some clinicians are reluctant to use porcelain restorations for anterior guidance.[63] While the wear characteristics of other materials may be good, they do not satisfy patient's esthetic demands. The constituents of a ceramic material also have an effect on its wear characteristics.[64] In addition, the higher the coefficient of friction between porcelain and the opposing material, the higher would be the fatigue and abrasive wear process of porcelain.[65]

The surface treatment of all-ceramic crowns may be responsible for the change in the rate of enamel wear. The adjustment, finishing, and contouring process for ceramic restorations play an important role in achieving function and optimal esthetics [Figure 4]. It is therefore important to consider various ceramic finishing and polishing systems to recreate the lost smoothness of the abraded ceramic surface to obtain maximum biocompatibility.[65,66,67] It is a well-recognized fact that improved esthetic results are achieved by polishing, and the ultimate goal of finishing and polishing ceramics is to obtain a surface that can serve as a substitute of a glazed porcelain so that wear of the opposing dentition and restoration could be reduced.[68,69,70] However, it is important to differentiate between surface integrity and a quantitative measure of surface smoothness.[71] Porcelain surface which is devoid of glaze will be virtually identical to a glazed surface in the view of surface smoothness, yet it will differ in terms of other characteristics, i.e. the wear, abrasion resistance, and stain absorption. Reglazing of a ceramic restoration may be done before its cementation in the mouth, but reglazing may not always be possible, especially once the restoration has been cemented and therefore, polishing becomes the best alternative.[72]

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscope image of an adjusted, polished surface of a ceramic

CONCLUSION

Technological advancements in dental ceramics are a fast and growing area in dental research and development. The esthetic appearance of ceramic restorations is attributable to surface texture of the restoration, which is determined by the surface finish. It is very important that clinicians are aware of recent advancements and that they should always consider the type of ceramic restorative materials used to maintain a stable occlusal relation. Further, the ceramic restorations should be adequately finished and polished after chair-side adjustment process of occlusal surfaces. Modifications of ceramic materials are recommended to produce more durable ceramic in terms of wear resistance and to minimize the undesired effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sulong MZ, Aziz RA. Wear of materials used in dentistry: A review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;63:342–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(90)90209-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shellis RP, Addy M. The interactions between attrition, abrasion and erosion in tooth wear. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;25:32–45. doi: 10.1159/000359936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiley MG. Effects of porcelain on occluding surfaces of restored teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61:133–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(89)90360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bani D, Bani T, Bergamini M. Morphologic and biochemical changes of the masseter muscles induced by occlusal wear: Studies in a rat model. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1735–44. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780111101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh WS, Delong R, Anusavice KJ. Factors affecting enamel and ceramic wear: A literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:451–9. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.123851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohlmann B, Trame JP, Dreyhaupt J, Gabbert O, Koob A, Rammelsberg P. Wear of posterior metal-free polymer crowns after 2 years. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:782–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levrini L, Di Benedetto G, Raspanti M. Dental wear: A scanning electron microscope study. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:340425. doi: 10.1155/2014/340425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanif A, Rashid H, Nasim M. Tooth surface loss revisited: Classification, etiology and management. J Res Dent. 2015;3:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huysmans MC, Chew HP, Ellwood RP. Clinical studies of dental erosion and erosive wear. Caries Res. 2011;45(Suppl 1):60–8. doi: 10.1159/000325947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitasako Y, Sasaki Y, Takagaki T, Sadr A, Tagami J. Age-specific prevalence of erosive tooth wear by acidic diet and gastroesophageal reflux in Japan. J Dent. 2015;43:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter S, Eliasson ST. Enamel erosion and mechanical tooth wear in medieval Icelanders. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74:186–93. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2015.1075586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etman MK, Woolford M, Dunne S. Quantitative measurement of tooth and ceramic wear: in vivo study. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Quinn JB, Romberg E, Arola D. On the brittleness of enamel and selected dental materials. Dent Mater. 2008;24:1477–85. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rashid H. Evaluation of the surface roughness of a standard abraded dental porcelain following different polishing techniques. J Dent Sci. 2012;7:184–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clelland NL, Agarwala V, Knobloch LA, Seghi RR. Relative wear of enamel opposing low-fusing dental porcelains. J Prosthodont. 2003;13:168–75. doi: 10.1016/S1059-941X(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passos SP, de Freitas AP, Iorgovan G, Rizkalla AS, Santos MJ, Santos Júnior GC. Enamel wear opposing different surface conditions of different CAD/CAM ceramics. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:743–51. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahalick JA, Knap FJ, Weiter EJ. Occlusal wear in prosthodontics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1971;82:154–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1971.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilathadka S, Vahalova D. Contemporary all-ceramic materials, part-1. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2007;50:101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Datla SR, Alla RK, Alluri VR, Babu J, Konakanchi A. Dental ceramics: Part II – Recent advances in dental ceramics. Am J Mater Eng Technolog. 2015;3:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rashid H. Comparing glazed and polished ceramic surfaces using confocal laser scanning microscopy. J Adv Microsc Res. 2012;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denry IL, Rosenstiel SF. In: Phase transformations in feldspathic dental porcelains. Bioceramics: Materials and Applications. Fischman G, Clare A, Hench L, editors. Westerville: The American Ceramic Society; 1995. pp. 149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guess PC, Schultheis S, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG, Ferencz JL, Silva NR. All-ceramic systems: Laboratory and clinical performance. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55:333–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fons-Font A, Solá-Ruíz MF, Granell-Ruíz M, Labaig-Rueda C, Martínez-González A. Choice of ceramic for use in treatments with porcelain laminate veneers. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly JR, Benetti P. Ceramic materials in dentistry: Historical evolution and current practice. Aust Dent J. 2011;56(Suppl 1):84–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atala MH, Gul EB. How to strengthen dental ceramics. Int J Dent Sci Res. 2015;3:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Noort R. Introduction to Dental Materials. Spain: Mosby; 1994. pp. 201–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien WJ. Magnesia ceramic jacket crowns. Dent Clin North Am. 1985;29:719–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien WJ, Groh CL, Boenke KM, Mora GP, Tien TY. The strengthening mechanism of a magnesia core ceramic. Dent Mater. 1993;9:242–5. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(93)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadaqah NR. Ceramic laminate veneers: Materials advances and selection. Open J Stomatol. 2014;4:268–79. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luthardt RG, Sandkuhl O, Reitz B. Zirconia-TZP and alumina – Advanced technologies for the manufacturing of single crowns. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 1999;7:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raut A, Rao PL, Ravindranath T. Zirconium for esthetic rehabilitation: An overview. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:140–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.79979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Part 3: Double veneer technique. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2007.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deany IL. Recent advances in ceramics for dentistry. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:134–43. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenoy A, Shenoy N. Dental ceramics: An update. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:195–203. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.73379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sukumaran VG, Bharadwaj N. Ceramics in dental applications, trends biomater. Artif Organs. 2006;20:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denry IL, Mackert JR, Jr, Holloway JA, Rosenstiel SF. Effect of cubic leucite stabilization on the flexural strength of feldspathic dental porcelain. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1928–35. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackert JR, Jr, Williams AL. Microcracks in dental porcelain and their behavior during multiple firing. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1484–90. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750070801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong JK, Luthy H, Wohlwend A, Schärer P. Heat-pressed ceramics: Technology and strength. Int J Prosthodont. 1992;5:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Höland W, Apel E, van't Hoen C, Rheinberger V. Studies of crystal phase formations in highstrength lithium disilicate glass-ceramics. J Non Cryst Solids. 2006;352:4041–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albakry M, Guazzato M, Swain MV. Influence of hot pressing on the microstructure and fracture toughness of two pressable dental glass-ceramics. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71:99–107. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fairhurst CW. Dental ceramics: The state of the science. Adv Dent Res. 1992;6:78–81. doi: 10.1177/08959374920060012101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taskonak B, Anusavice KJ, Mecholsky JJ., Jr Role of investment interaction layer on strength and toughness of ceramic laminates. Dent Mater. 2004;20:701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mörmann WH. The evolution of the CEREC system. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:7S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyazaki T, Hotta Y, Kunii J, Kuriyama S, Tamaki Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: Current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent Mater J. 2009;28:44–56. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaiyabutr Y, Kois JC, Lebeau D, Nunokawa G. Effect of abutment tooth color, cement color, and ceramic thickness on the resulting optical color of a CAD/CAM glass-ceramic lithium disilicate-reinforced crown. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;105:83–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alghazzawi TF, Lemons J, Liu PR, Essig ME, Janowski GM. Evaluation of the optical properties of CAD-CAM generated yttria-stabilized zirconia and glass-ceramic laminate veneers. J Prosthet Dent. 2012;107:300–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(12)60079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shammas M, Alla RK. Color and shade matching in dentistry, trends biomater. Artif Organs. 2011;25:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burwell J. Survey of possible wear mechanisms. Wear. 1957;1:119–41. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hmaidouch R, Weigl P. Tooth wear against ceramic crowns in posterior region: A systematic literature review. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5:183–90. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rashid H. The effect of surface roughness on ceramics used in dentistry: A review of literature. Eur J Dent. 2014;8:571–9. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.143646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jagger DC, Harrison A. An in vitro investigation into the wear effects of unglazed, glazed, and polished porcelain on human enamel. J Prosthet Dent. 1994;72:320–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(94)90347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harrison A, Lewis TT. The development of an abrasion testing machine for dental materials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1975;9:341–53. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820090309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derand P, Vereby P. Wear of low-fusing dental porcelains. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:460–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metzler KT, Woody RD, Miller AW, 3rd, Miller BH. In vitro investigation of the wear of human enamel by dental porcelain. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:356–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clelland NL, Agarwala V, Knobloch LA, Seghi RR. Relative wear of enamel opposing low-fusing dental porcelain. J Prosthodont. 2003;12:168–75. doi: 10.1016/S1059-941X(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheung KC, Darvell BW. Sintering of dental porcelain: Effect of time and temperature on appearance and porosity. Dent Mater. 2002;18:163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(01)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeLong R, Douglas WH, Sakaguchi RL, Pintado MR. The wear of dental porcelain in an artificial mouth. Dent Mater. 1986;2:214–9. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(86)80016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly JR, Campbell SD, Bowen HK. Fracture-surface analysis of dental ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;62:536–41. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(89)90075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rasmussen ST, Ngaji-Okumu W, Boenke K, O'Brien WJ. Optimum particle size distribution for reduced sintering shrinkage of a dental porcelain. Dent Mater. 1997;13:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(97)80007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anusavice KJ, Lee RB. Effect of firing temperature and water exposure on crack propagation in unglazed porcelain. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1075–81. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680060401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piddock V. Effect of alumina concentration on the thermal diffusivity of dental porcelain. J Dent. 1989;17:290–4. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(89)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monasky GE, Taylor DF. Studies on the wear of porcelain, enamel, and gold. J Prosthet Dent. 1971;25:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(71)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang L, D'Alpino PH, Lopes LG, Pereira JC. Mechanical properties of dental restorative materials: Relative contribution of laboratory tests. J Appl Oral Sci. 2003;11:162–7. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572003000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imai Y, Suzuki S, Fukushima S. Enamel wear of modified porcelains. Am J Dent. 2000;13:315–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schuh C, Kinast EJ, Mezzomo E, Kapczinski MP. Effect of glazed and polished surface finishes on the friction coefficient of two low-fusing ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Podshadley AG, Harrison JD. Rat connective tissue response to pontic materials. J Prosthet Dent. 1966;16:110–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Wahadni AM, Martin DM. An in vitro investigation into the wear effects of glazed, unglazed and refinished dental porcelain on an opposing material. J Oral Rehabil. 1999;26:538–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1999.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobi R, Shillingburg HT, Jr, Duncanson MG., Jr A comparison of the abrasiveness of six ceramic surfaces and gold. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;66:303–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90254-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pascal M, Belser U. Bonded Porcelain Restorations in the Anterior Dentition. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing 2002; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Hiyasat AS, Saunders WP, Smith GM. Three-body wear associated with three ceramics and enamel. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;82:476–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patterson CJ, McLundie AC, Stirrups DR, Taylor WG. Polishing of porcelain by using a refinishing kit. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:383–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90229-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wright MD, Masri R, Driscoll CF, Romberg E, Thompson GA, Runyan DA. Comparison of three systems for the polishing of an ultra-low fusing dental porcelain. J Prosthet Dent. 2004;92:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]