IL-6/STAT3 signaling modulates the cytokine and transcription factor pattern of Tfh cells and controls IgE secretion in vivo.

Keywords: Tfh-2, STAT3, humoral response

Abstract

Follicular helper T cells (Tfh) support high-affinity Ab production by germinal center B cells through both membrane interactions and secretion of IL-4 and -21, two major cytokines implicated in B-cell survival and Ab class switch. Tfh-2 cells recently emerged in humans as a strong IL-4 producer Tfh cell subset implicated in both autoimmune and allergic diseases. Although the molecular mechanisms governing Tfh cell differentiation from naive T cells have been widely described, much less is known about the regulation of cytokine secretion by mouse Tfh-2 cells. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the role of dendritic cell–derived IL-6 in fine-tuning cytokine secretion by Tfh cells. Our results demonstrate that priming of Th cells by IL-6-deficient antigen-presenting dendritic cells preferentially leads to accumulation of a subset of Tfh cells characterized by high expression of GATA3 and IL-4, associated with reduced production of IL-21. STAT3-deficient Tfh cells also overexpress GATA3, suggesting that early IL-6/STAT3 signaling during Tfh cell development inhibits the expression of a set of genes associated with the Th2 differentiation program. Overall, our data indicate that IL-6/STAT3 signaling restrains the expression of Th2-like genes in Tfh cells, thus contributing to the control of IgE secretion in vivo.

Introduction

Tfh cells represent a specialized Th cell subset that provides crucial signals to B lymphocytes and guides high-affinity isotype-switched Ab responses and memory B-cell development [1]. Upon infection or vaccination, T lymphocytes are first activated in the T-cell zone of the draining lymph node after encounter of their cognate antigen along with costimulatory signals provided by DCs. Tfh precursor cells then start to express the transcriptional repressor BCL6, considered to be the critical master regulator of Tfh cell development in vivo [2, 3]. Pre-Tfh cells express CXCR5 and repress expression of CCR7, allowing them to relocalize at the T–B border zone, where they receive additional signals from B cells [4]. This second wave of interactions further stabilizes the Tfh cell fate (characterized by higher expression of BCL6 and surface markers, such as CXCR5, PD1, ICOS) and results in migration toward the GC and delivery of optimal helper signals to B cells [4, 5].

Recent studies—in particular, those performed in clinical settings—have led to the recognition of functional heterogeneity among Tfh cells. In human blood, CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells represent a circulating pool of memory Tfh cells that can be distinguished based on the selective expression of chemokine receptors and cytokine profile into CXCR3+ Tfh-1, CCR6+ Tfh-17, and CXCR3− CCR6− Tfh-2 cells, among which the Tfh-2 and -17 subsets are endowed with B-cell help capacities [6]. Tfh-2 cells produce IL-4, a cytokine originally identified as a B-cell-stimulating factor with an important role in the regulation of class-switch recombination of B cells toward IgG1- and IgE-secreting plasma cells. This combined capacity to localize to GCs and produce IL-4 suggests a potential role for this T-cell subset in several important (patho)-physiologic situations, such as helminth immune response, allergy, autoimmunity, and B-cell lymphomas [6–13]. Accordingly, skewing of blood Tfh cells toward Tfh-2 cells is observed in several cancers and inflammatory diseases [7–11]. In particular, increased Tfh-2 cell proportion seems to correlate with the presence of high anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies and IgE levels in the sera of patients with active lupus [7]. Together, these data indicate that Tfh-2 cells may be involved in the progression of cancer and inflammatory diseases and point to modifications of Tfh effector molecules or Tfh subset balance as future therapeutic targets. However, Tfh cell subsets have not been studied in mice and the molecular mechanisms that fine tune the cytokine profile of Tfh cell subsets remain unclear.

IL-6 and -12 have been identified as important drivers of Tfh cell differentiation in both human and animal models [14–21]. In addition, IL-6 and -12 have been shown, by us and others, to constrain Th2 responses, thus positioning these cytokines as likely candidates in the control of Tfh-2 cell development in vivo [22–24]. By taking advantage of an immunization protocol based on antigen-loaded, BMDCs deficient in IL-6 or in the IL-12/IL-35 common p35 chain, we analyzed the potential contribution of these APC-derived cytokines in Tfh cell differentiation, with a particular focus on the Tfh-2 cell subset. Immunization of WT mice with IL-6- but not IL-12-deficient BMDCs led to increased secretion of antigen-specific IgE and to the differentiation of Th cells displaying a typical Tfh-2 profile, characterized by increased expression of IL-4 and GATA3, thus suggesting a major role for IL-6-derived APCs in the fine tuning of Tfh cell responses in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Nederland (Horst, The Netherlands). IL-6−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). STAT3flox/flox mice (on a C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Dr. Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan), CD4-CRE (C57BL/6 background) mice by Dr. Geert Van Loo (University of Gent, Gent, Belgium), and 4-get mice by Dr. Bart Lambrecht (University of Gent). STAT3flox/flox and CD4-CRE mice were bred to generate T-cell compartment-specific STAT3-deficient mice (referred as STAT3CD4−/−). IL-12p35 mice, described elsewhere [23], were back-crossed to a C57BL/6 background and kindly provided by Dr. Eric Muraille (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium).

All mice were used at 6–12 wk of age. The experiments were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines and were approved by the local ethics committee.

Differentiation of BMDCs and in vitro stimulation

Bone marrow cells were collected from naive mice and grown for 8 d in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 0.1% 2-ME, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 20 ng/ml recombinant murine GM-CSF (provided by Professor Kris Thielemans, Medical School of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel). At d 8, BMDCs were pulsed overnight with 30 μg/ml KLH (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA) in the presence of 1 μg/ml LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B5; Thermo Fisher Scientific). At d 9, the BMDCs were collected and injected into recipient mice.

Immunization and Ab detection

KLH-pulsed LPS-treated BMDCs were injected at a dose of 5 × 105 cells into the hind footpads of recipient mice. Draining popliteal lymph node cells were harvested 7 d after immunization. In some experiments, mice were immunized with 10 μg nitrophenyl-KLH (NP25-KLH; Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA, USA) or KLH with 1 mg of Imject Alum (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Serum levels of NP- or KLH- specific antibodies were determined on d 14 by ELISA, according to standard procedures. In brief, ELISA plates were coated with 5 μg/ml KLH or 2 μg/ml NP-BSA and incubated with serial dilutions of sera in duplicate wells. Bound antibodies were revealed with peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse isotype-specific rat monoclonal antibodies (IMEX; Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium) followed by the peroxidase substrate tetramethylbenzidine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A total of 2 N H2SO4 was used to quench the reaction, and ODs were quantified at 450 nm and converted to units based on a standard curve obtained from a previously available immunized serum arbitrarily defined at 1000 U/ml.

The relative affinities of NP-immune sera were calculated by comparing their binding to differently haptenized carrier proteins (heavily haptenized NP18-BSA vs. lightly haptenized NP2-BSA; Biosearch Technologies, Inc., Petaluma, CA, USA) [25]. The same serial dilutions of each serum sample were allowed to bind on NP18-BSA and NP2-BSA. The relative affinities of the anti-NP serum antibodies are expressed as a ratio of the serum volumes required to give the 50% of maximum binding on NP18-BSA divided by the volumes necessary for same binding on NP2-BSA (serum relative affinity = vol50% binding on NP18-BSA/vol50% binding on NP2-BSA).

Flow cytometry

Specific cell-surface staining was performed using a standard procedure with anti-CD4, anti-PD1 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-CXCR5 mAbs (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

For ICS, primed cells were restimulated for 4 h with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycine (250 ng/ml) (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in the presence of monensin (1:1000) (eBioscience). The cells were fixed and permeabilized with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) and stained in a 2-step procedure with APC-conjugated anti-mouse IL-4 or anti-IFN-γ (BD Bioscience) and recombinant mouse IL-21R Subunit, Human Fc Chimera (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), followed by PE-conjugated anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA).

Intracellular GATA3, FoxP3, BCL6, Ki67 (Ab from BD Bioscience), and T-bet (eBioscience) staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (FoxP3 staining set protocol; eBioscience). Cells were separated by flow cytometry with a FACS Arria (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo Software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

B-cell help

Serial dilutions of FACS-sorted Tfh cells (gate CD4+CXCR5+PD1+) were cocultured for 7 d with syngeneic B cells purified from KLH/Alum immunized mice (5 × 104 cells/well) in the presence of 10 μg/ml KLH. IgG1 and IgE antibodies in the supernatants were determined by ELISA, with rat anti-mouse isotype mAb (IgG1 detection: capture Ab loMG1.13, detection Ab loMK.1; IgE detection: capture Ab loME.3, detection Ab loME.2, all from IMEX). Purified mouse IgG1 or IgE (BD Biosciences) was used as a standard reference. Anti-mouse IL-4 mAb (clone 11B11; BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) was added (10 μg/ml) to selected cocultures.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted by using the TRIzol method (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reverse transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed by using the SYBR Green Master mix kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. Differences reaching P < 0.05 were significant.

RESULTS

IL-6-deficient BMDCs induce altered cytokine and transcription factor expression profiles in Tfh cells

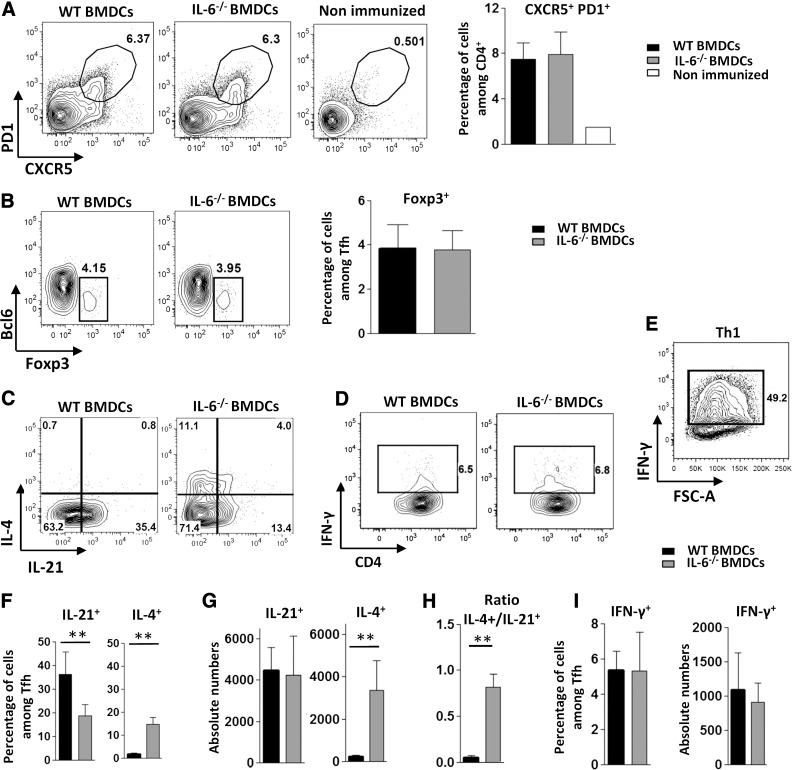

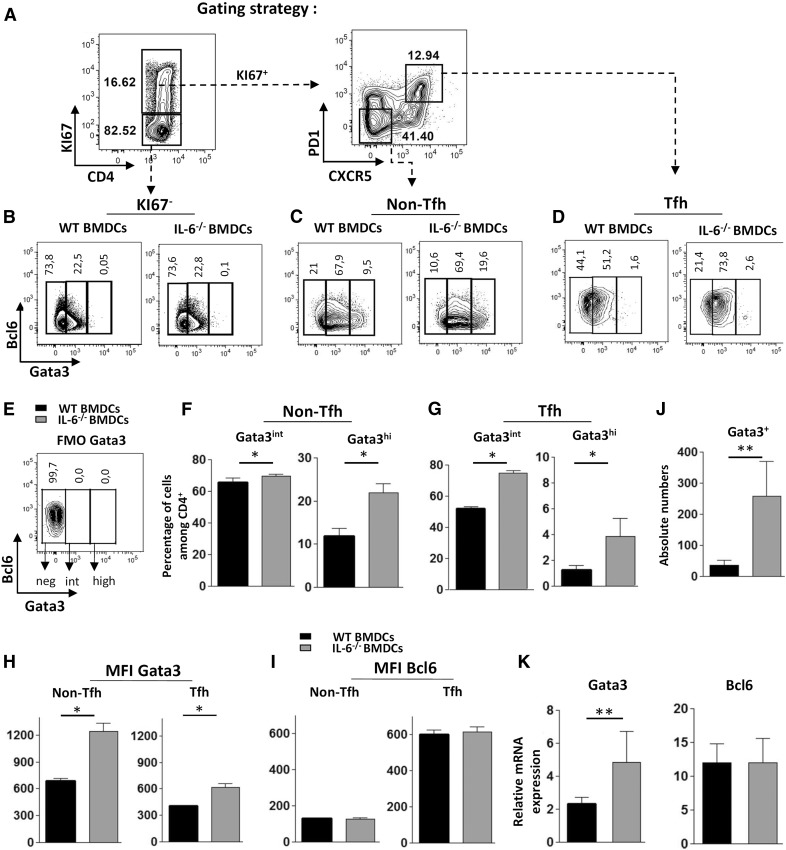

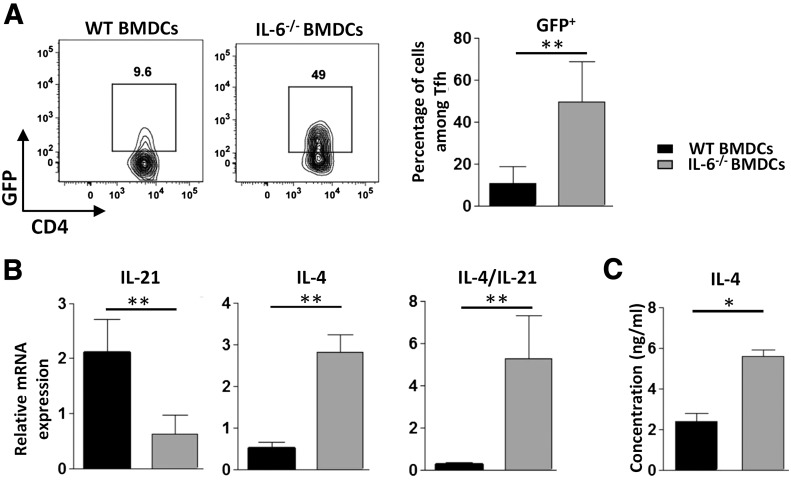

To specifically address the potential role of APC-derived IL-6 in the regulation of Tfh response, we immunized C57BL/6 mice with WT or IL-6-deficient BMDCs loaded with KLH and analyzed the CD4+ Th cell response 7 d later. IL-6-deficient BMDCs induced normal expansion of cells expressing a typical Tfh phenotype (Fig. 1A). The percentage of Foxp3+ regulatory follicular cells (Tfr) among the CXCR5+ PD1+ CD4+ T cell subset was similar in the two experimental groups (Fig. 1B). Tfh cells from antigen-loaded IL-6-KO BMDC-inoculated mice expressed optimal levels of BCL6 (see Fig. 3D, I), further indicating that IL-6 delivery at the time of the DC-T cell synapse was dispensable for the generation of Tfh cells in this experimental setting. Compared to the control condition, Tfh cells induced in the absence of DC-derived IL-6 expressed an altered cytokine pattern, characterized by reduced percentage of IL-21+ and increased proportion and absolute number of IL-4+ Tfh cells (Fig. 1C, F, G). Although the absolute number of IL-21-secreting Tfh cells was not reduced in this experiment, a stronger IL-4+/IL-21+ Tfh cell number ratio was consistently observed in mice immunized by IL-6-deficient BMDCs (Fig. 1H). Secretion of IFN-γ was not significantly affected in this experimental setting (Fig. 1D, I). Increased IL-4 production induced by DCs lacking IL-6 secretion was confirmed in IL-4-reporter mice (4-get mice, revealing IL-4 gene transcription; Fig. 2A). This altered cytokine profile was further confirmed by RT-qPCR performed on ex vivo sorted Tfh cells. In agreement with the results obtained in the 4-get model, expression of the IL-4-encoding mRNA was upregulated in Tfh cells that developed upon priming with an IL-6-deficient protocol. IL-21 mRNA expression was inhibited in this cell population, thus leading to a strong increase in the IL-4/IL-21 mRNA ratio in Tfh cells from IL-6-KO BMDC-immunized mice (Fig. 2B). Tfh cells separated by FACS were restimulated in vitro in the presence of anti-CD3 mAbs. Analysis of their culture supernatant by ELISA confirmed increased IL-4 secretion by Tfh cells from the IL-6-KO-immunized group of mice (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1. Immunization with IL-6-deficient BMDCs alters cytokine secretion by Tfh cells.

WT mice were immunized by footpad injection of 5 × 105 LPS-stimulated, KLH-pulsed BMDCs derived from WT or IL-6-KO mice. Draining LN cells were recovered on d 7 and (A, B) analyzed for Tfh cell marker expression or (C–I) stimulated with ionomycin and PMA in the presence of monensin to evaluate cytokine production by ICS. Contour plots and histograms in (A) illustrate CXCR5 and PD1 staining profiles of CD4+ live cells within an FSC-A/FSC-W gate, enabling exclusion of doublets and triplets of cells; contour plots in (B–D) represent BCL6 and Foxp3 or IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-21 staining profiles of Tfh cells (CXCR5+ PD1+) gated as indicated in (A); a positive control for IFN-γ staining (in vitro derived Th1 cells) is also included in (E); (F, G, I) Percentage and absolute number of IL-21-, IL-4- or IFN-γ-secreting Tfh cells; (H) ratio of total number of IL-4+ to IL-21+ Tfh cells. Results represent means ± sd of 5–6 individual mice and are representative of at least 10 (A) or 5 (C–I) independent experiments or are pooled from 4 independent experiments (B, n = 15). Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. **P < 0.01. See also Supplemental Fig. S1 for gating strategy and staining controls.

Figure 3. IL-6-deficient BMDCs promote expression of GATA3 in Tfh cells.

WT mice were immunized with KLH-pulsed WT or IL-6−/− BMDCs, as in Fig. 1. Seven days later, GATA3 and BCL6 expression was measured by ICS. (A) Contour plots illustrate the gating strategy to identify CD4+Ki67− and CD4+Ki67+ within viable singlet cells (left) and Tfh and non-Tfh cells among the CD4+Ki67+ gated cells (right); (B–G) contour plots and histograms represent the percentage of GATA3int and GATA3high cells in Ki67−, Ki67+ non-Tfh and Ki67+ Tfh+ gated cells; (E) FMO control for GATA3 staining; (H, I) histograms of GATA3 or BCL6 expression intensity (expressed as mean fluorescence intensity) among Tfh and non-Tfh cell subsets; (J) absolute number of GATA3+ (intermediate + high expression) Tfh cells in both experimental groups; and (K) mRNA expression levels of GATA3 and BCL6 (relative to RPL32 mRNA) in Tfh cells sorted as in Fig. 2. Results are representative of 3 (A–J) or 2 (K) independent experiments and are means ± sd of 5–6 individual mice. Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Figure 2. IL-6-secreted by BMDCs damps IL-4 mRNA expression and IL-4 secretion by Tfh cells.

(A) The 4-get mice were immunized as in Fig. 1. Contour plots and histograms represent the percentage of GFP+ cells among the gated Tfh cells; (B, C) Tfh cells from C57BL6 mice immunized with WT or IL-6−/− BMDCs were separated by FACS and tested for (B) IL-4 and -21 mRNA expression ex vivo by RT-qPCR (expression was normalized to RPL32) or (C) restimulated with plastic-coated anti-CD3 mAbs for 24 h to allow detection of IL-4 secretion by ELISA. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments and are the means ± sd of 5–6 individual mice (A, B) or means ± SD of 4 individual culture wells. Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Expression of BCL6 and GATA3 transcription factors among antigen-activated (Ki67+) Tfh cells and non-Tfh cells was then analyzed (see Fig. 3A for gating strategy). In particular, the percentage of Tfh cells expressing intermediate or high levels of GATA3 expression was estimated. In agreement with the previously established cytokine secretion pattern, these experiments revealed a significant expansion of Tfh-2 cells in mice immunized with IL-6-deficient BMDCs. Indeed, although lack of APC-derived IL-6 did not preclude expression of BCL6 expression in Tfh cells, it led to a significant increase in GATA3 expression by these CXCR5+PD1+ cells (as judged by increased percentage and absolute number of Tfh cells expressing GATA3; Fig. 3D, G, J). It is noteworthy that a small but significant percentage of Tfh cells reached high GATA3 expression level (similar to the Th2 cell expression level, see hereafter) in the IL-6-deficient BMDC experimental group (Fig. 3D and 3G, right). In agreement with our own observations [24], lack of IL-6 at antigen encounter promoted Th2 cell development, as indicated by the increased percentage of GATA3hi cells in proliferating (Ki67+), non-Tfh (CXCR5−, PD1−, and BCL6−) cells, thus identifying these cells as bona fide Th2 lymphocytes. (Fig. 3C, F). Only low levels of BCL6 and GATA3 were detectable in the Ki67− CD4+ cells, in keeping with the notion that expression of these two transcription factors requires TcR-derived signals (Fig. 3B). Increased GATA3 expression in Tfh cells of mice inoculated with IL-6-deficient BMDCs was further confirmed by mean fluorescence intensity analysis (Fig. 3H, right) and by RT-qPCR analysis of Tfh cells identified by FACS (Fig. 3K). Overall, these observations point to a role for IL-6 in restraining the development of IL-4-producing, GATA3-expressing Tfh (Tfh-2) lymphocytes upon antigen stimulation in vivo.

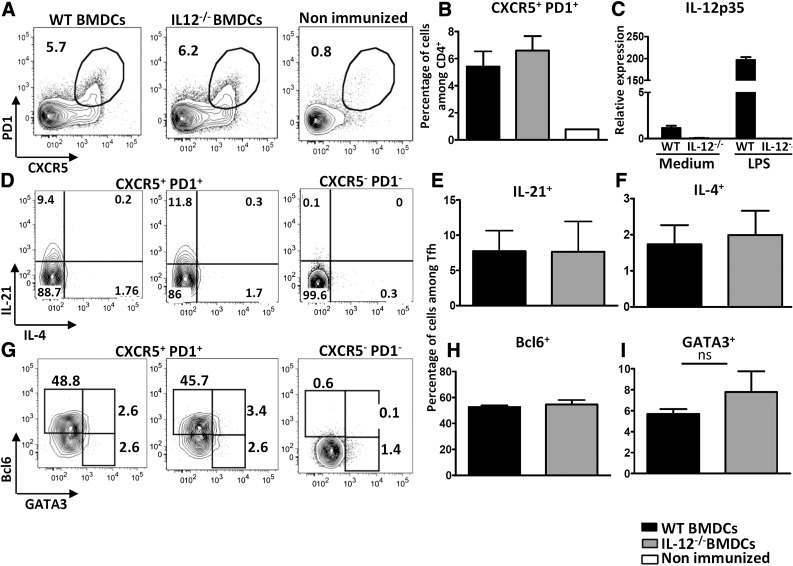

IL-12 is dispensable for induction of Tfh cells upon antigen-loaded BMDC immunization

As IL-12 has been shown to promote Tfh cell differentiation in vivo and to oppose Th2 development [21, 22], we sought to investigate whether IL-12 exerts the same effects as IL-6 on Tfh cell development. KLH-loaded, WT, or IL-12p35-deficient BMDCs were injected into C57BL6 mice, by using the same protocol as described earlier. The results clearly showed that IL-12 deficiency in APCs during T-cell priming neither precluded Tfh differentiation nor altered their IL-21/IL-4 secretion pattern (Fig. 4A–F).

Figure 4. Immunization with IL-12-deficient BMDCs does not alter Tfh cell differentiation.

WT mice were immunized with KLH-pulsed WT or IL-12p35−/− BMDCs. Draining lymph node cells were recovered on d 7 (A, B, G–I) and analyzed for Tfh cell marker and transcription factor expression or (D–F) stimulated with ionomycin and PMA in the presence of monensin to evaluate IL-4 and -21 production by ICS. Contour plots and histograms illustrate CXCR5 and PD1 staining profiles of CD4+ live singlet cells (A); BCL6, GATA3, IL-4, and IL-21 among Tfh gate (D–I); and (C) mRNA expression of IL-12p35 following a 3 h stimulation of BMDCs with 1 µg/ml LPS [expression was normalized to RPL32 and the results are presented as fold induction compared to WT nonstimulated (NS) BMDC sample set at 1]. Results are means ± sd of 5 individual mice and are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Tfh cells slightly expressed T-bet in this experimental setting and, as expected, T-bet expression was reduced in the IL-12-deficient BMDC-inoculated group (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, and in agreement with the cytokine secretion profile, GATA3 expression did not significantly increase in mice immunized with IL-12-KO BMDCs (Fig. 4G, I).

To confirm that Tfh cells may differentiate in vivo in the absence of APC-derived IL-6 and -12, we next immunized mice with antigen-loaded IL-6/IL-12 DKO BMDCs. Results in Supplemental Fig. 2B showed normal frequencies of CXCR5+ PD1+ Th in WT and DKO BMDC-inoculated groups. Similar GATA3 up-regulation was observed in Tfh cells of IL-6-KO and IL-6/IL-12-DKO groups of mice, further confirming the specificity of IL-6 in containing the magnitude of Th2 features in Tfh cells (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

APC-derived IL-6 delivery at the time of Tfh priming governs Ab isotype class switch

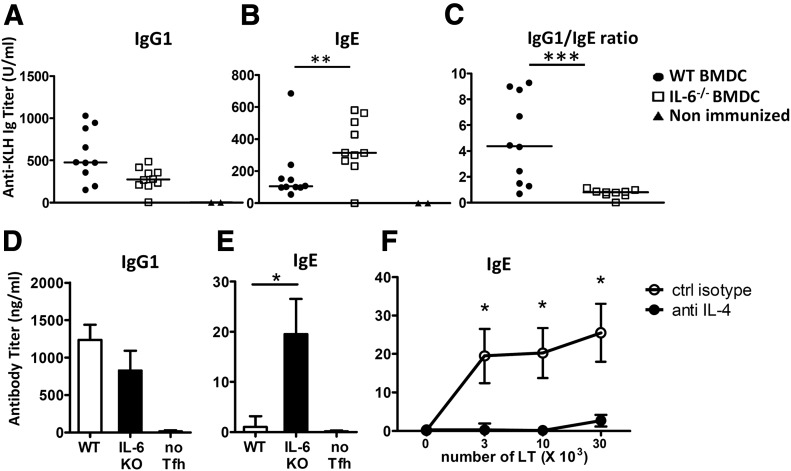

Because IL-4 and -21 exert opposite roles on IgG1 and IgE class switch, we next analyzed the humoral response of mice primed with IL-6-deficient APCs. In agreement with the cytokine profile of Tfh cells, DCs lacking IL-6 promoted increased antigen-specific IgE secretion (Fig. 5B). Although IgG1 was not significantly altered in mice immunized with IL-6-KO DCs, the mice expressed a severely decreased antigen-specific IgG1/IgE ratio (Fig. 5A, C).

Figure 5. IL-6-deficient BMDCs promote IgE secretion.

WT mice were immunized with KLH-pulsed WT or IL-6−/−BMDCs, as in Fig. 1. (A–C) Sera were tested on d 14 for KLH-specific IgG1 (A) and IgE (B) contents; (C) relative levels of IgG1 to IgE NP-specific antibodies for each mouse. Results are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n = 10). (D–F) Tfh cells (gate CD4+CXCR5+PD1+) were separated by FACS and cultured for 7 d with purified syngeneic B cells purified from KLH/Alum immunized mice (5 × 104 cells/well) and 10 μg/ml KLH. Histograms in (D, E) represent IgG1 and IgE secretion by B cells cultured alone or with 3 × 104 Tfh cells purified from WT or IL-6−/− BMDC inoculated mice; (F) IgE secretion by B cells cultured with KLH and Tfh cells from IL-6−/− BMDC mice in the presence or absence or anti-IL-4 mAbs. Results are expressed as means ± sd of 4 individual culture wells and are representative of 2 independent experiments. Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To further evaluate whether Tfh-2 cells primed in the absence of IL-6 were intrinsically able to promote IgE secretion by B cells, we used FACS to separate Tfh cells from control and IL-6-KO BMDC-immunized mice and cultured them in the presence of purified B lymphocytes and KLH. Control Tfh cells induced IgG1 secretion by activated B cells and barely detectable IgE secretion. In accordance with the in vivo data, Tfh cells primed in the absence of DC-derived IL-6 induced IgE secretion in vitro, whereas IgG1 production was slightly decreased (Fig. 5D, E). It is noteworthy that Tfh-induced IgE secretion was completely inhibited by the addition of anti-IL-4 Ab in the T–B coculture medium (Fig. 5F). The collective results suggest that IL-6 provided by APCs during in vivo priming affects the humoral response by restraining the development of Tfh-2 lymphocytes.

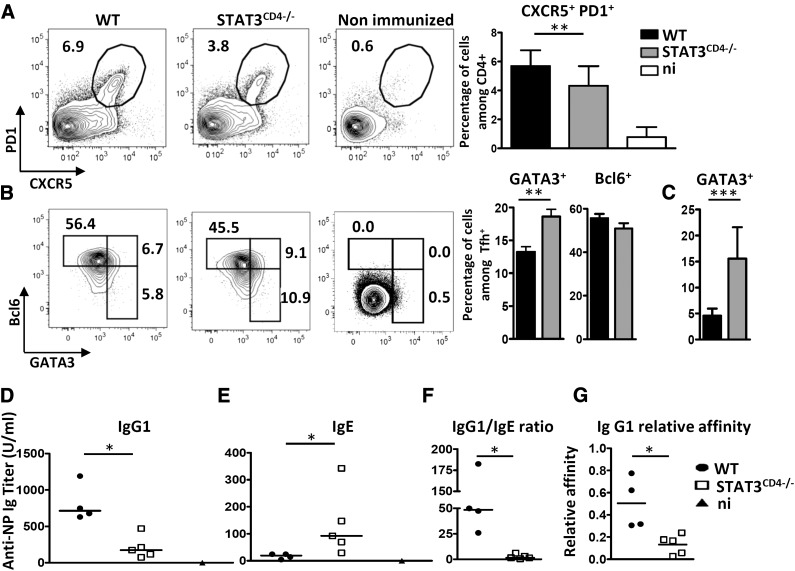

STAT3 signaling restricts GATA3 expression in Tfh cells and regulates the capacity of Tfh cells to provide B-cell help in vivo

Because STAT3 is the major signaling pathway activated by IL-6 [26], we investigated the influence of this transcription factor on the expression of GATA3 in Tfh cells. We immunized WT and STAT3fl/fl/CD4-CRE (referred to as STAT3CD4−/−) mice with antigen (KLH or NP-KLH) formulated with the pro-Th2 Alum adjuvant. STAT3CD4−/− mice displayed a mild, but significant, reduction in number of Tfh cells (Fig. 6A). Total percentages of Ki67+ Th cells were similar or even increased in STAT3CD4−/− mice, thus suggesting that the reduction in the number of Tfh cells did not result from general attenuation of Th cell response toward the antigen/Alum formulation (data not shown). Intracellular transcription factor staining revealed that STAT3 deficiency resulted in up-regulation of GATA3 expression by Tfh cells, associated with normal levels of BCL6 expression (Fig. 6B). Increased GATA3 expression in the Tfh cell compartment of STAT3CD4−/− mice was observed similarly when these mice were immunized with antigen-pulsed WT BMDCs (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Immunization of STAT3CD4−/− mice results in higher expression of GATA3 in Tfh cells and altered IgG1 and IgE isotype secretion.

STAT3fl/fl and STAT3fl/fl CD4-CRE mice were immunized with NP-KLH in Alum. Draining lymph nodes were analyzed on d 7 for Tfh cells (CXCR5+PD1+) among viable CD4+ cells (A) and GATA3/BCL6 expression among Tfh cells (B). (C) Percentage of GATA3+ cells among Tfh cells in STAT3fl/fl and STAT3fl/fl CD4-CRE mice immunized with KLH-pulsed WT-BMDCs as in Fig. 3. (D–G) Individual sera from mice in (A) were tested on d 14 for NP-specific IgG1 (D) and IgE (E) contents; (F) relative levels of IgG1 to IgE NP-specific antibodies for each mouse; (G) sera from (D) were tested for NP affinity. Relative affinities are expressed as the ratio of 50% binding on NP18- and NP2-BSA. Results in (A, B) are pooled from 2 to 5 independent experiments (n = 23, A; n = 11, B) or are representative of 3 independent experiments (C–G). n.i., nonimmunized. Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for 2-tailed data. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

In keeping with these data, STAT3CD4−/− mice displayed reduced NP-specific IgG1 response, and enhanced NP-specific IgE production when compared to control mice (Fig. 6D–F). Moreover, mice with T cells lacking STAT3 expression did not show the secretion of high-affinity NP-specific IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 6G), suggesting that STAT3-signaling constrains Tfh-2 cell subset development and controls both the isotype switch and affinity maturation processes induced by Tfh cells.

DISCUSSION

Although Tfh-2 subsets have been widely described in humans, little is known about their putative relatives in mice. In particular, the stimuli that specifically drive Tfh-2 cell subset differentiation are still ill defined, thus precluding preclinical studies.

In our study, priming of Th cells in the absence of DC-secreted IL-6 preferentially led to accumulation of a subset of Tfh cells expressing higher amounts of GATA3, associated with increased secretion of IL-4, therefore indicating that Tfh cells expressing features of Tfh-2 cells can be induced in mice and that IL-6 is a key factor restraining Tfh-2 cell subset development in vivo.

Although Tfh differentiation is clearly a multifactorial process implying several cytokines and transcription factors [27–29], a major role for IL-6 in driving Tfh differentiation has been emphasized in several publications [14, 15, 17, 18, 30–33], together with the identification of potential cellular sources of this cytokine in vivo [17, 18, 34]. However, IL-6 was found dispensable for early Tfh generation in some studies [14, 30, 35]. Our study demonstrated that the early (concomitant with antigen presentation) provision of IL-6 signals is dispensable for expansion of antigen-specific Tfh cells (defined as CD4+CXCR5+PD1+), but imprints Tfh subset cell fate by down-regulating key Tfh-2 cell features, such as GATA3 and IL-4 expression. Thus, our study may help in reconciling previous apparently contradictory results in which IL-6 was found dispensable for adequate Tfh generation by assuming that, depending on the cell type and timing of delivery, IL-6 may either promote Tfh cell generation or constrain IL-4 secretion, thereby specifically fine tuning Tfh subset development.

Beside its role on Tfh cell function, IL-6 has been shown to impede Th2 proinflammatory responses in vivo through both Treg-dependent and independent mechanisms [24, 36]. In our study, we showed that IL-6 secreting DCs down-regulated IL-4 secretion and GATA3 expression without significantly affecting Tfr (Fig. 1) or Treg (data not shown) cell differentiation. Thus, although the functional suppressive activity of Tfr cells was not evaluated in this study, our results are best explained by assuming that IL-6 signaling induces a Tfh cell autonomous down-regulation of GATA3 expression, thereby restraining development of Tfh-2 features. In keeping with this assumption, STAT3 signaling is essential for controlling GATA3 expression in Tfh cells (Fig. 6 and [37]).

Our data showing a normal level of BCL6 expression in WT and STAT3-deficient Tfh cells contrasts with recent work suggesting a BCL6-repressing role for STAT3 in Tfh cells [37]. The reason for this discrepancy remains unresolved at this time, but may be related to distinct antigen formulations between the two studies. In particular, use of a pro-Th2 adjuvant (Alum) in the present study may have favored expression of GATA3, a known BCL6 antagonist [38, 39]. In this setting, the early upregulation of GATA3 expression in STAT3-deficient mice may have precluded BCL6 up-regulation. The present findings are in agreement with our own previous observations demonstrating that STAT3-defiency in Th2 cells is associated with an increased GATA3/BCL6 expression ratio [40].

Finally, the isotypic profile appears to be under the influence of the cytokine cocktail produced by the Tfh cells. Based on the well-known capacities of IL-4 and -21 to promote and oppose the IgE class switch, respectively [41, 42], we speculate that the IL-6/STAT3 axis plays an important role in limiting the secretion of IgE antibodies by fine tuning the cytokine secretion pattern of Tfh cells during T–B interaction. Note that the immune alterations observed in mice lacking STAT3 expression appear to be more severe when compared to the immune response induced in WT mice by IL-6-deficient APCs. Indeed, whereas both groups were characterized by enhanced IgE secretion, STAT3-deficient mice displayed a strongly reduced IgG1 response, further characterized by a lack of affinity maturation. We believe that additional contribution of host-derived IL-6 and -21 may partially compensate for the lack of APC-derived IL-6 in WT mice, enabling sufficient STAT3 signaling in these mice to allow Tfh cell help for IgG1 secretion. In any event, our study confirmed the important role of IL-6 and STAT3 in precluding Tfh cells to acquire Tfh-2-like properties.

In conclusion, the present study revealed a more complete picture of how DC-driven IL-6 production may affect the outcome of Tfh cell development and function. We believe that the capacity to modulate IL-6/STAT3 signaling in vivo may provide novel clues for the development of long-term humoral immunity in response to vaccines and pave the way to innovative treatments of allergic diseases.

AUTHORSHIP

M.H. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.A., S.D., and D.D. performed the experiments; F.A. and O.L. contributed to the study’s conception, design, and data analyses and wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The Belgian Program in Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Initiated by the Belgian State, Prime Minister’s office, Science Policy Programming; by a Research Concerted Action of the Communauté Française de Belgique; by a grant from the Fonds Jean Brachet; and research credit from the National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS), Belgium. F.A. is a Research Associate at the FNRS. D.D. was recipient of a research fellowship from the FNRS/Télévie and from the Fond David et Alice Van Buuren, Belgium. M.H. was supported by a Belgian FRIA fellowship. The authors thank Caroline Abdelaziz and Véronique Dissy for animal care and for technical support and Kris Thielemans (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) for generously providing the recombinant GM-CSF.

Glossary

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- Bcl

B-cell lymphoma

- BMDC

bone marrow–derived dendritic cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- DKO

double knockout

- Foxp

Forkhead box protein

- GATA

GATA binding protein

- GC

germinal center

- ICS

intracellular cytokine staining

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- KO

knockout

- NP

4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl

- PD1

programmed cell death 1

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- T-bet

T-box expressed in T-cells

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- Tfh

T follicular helper cell

- TL

T lymphocyte

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 1

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crotty S. (2011) Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 621–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston R. J., Poholek A. C., DiToro D., Yusuf I., Eto D., Barnett B., Dent A. L., Craft J., Crotty S. (2009) Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science 325, 1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nurieva R. I., Chung Y., Martinez G. J., Yang X. O., Tanaka S., Matskevitch T. D., Wang Y. H., Dong C. (2009) Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science 325, 1001–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi Y. S., Kageyama R., Eto D., Escobar T. C., Johnston R. J., Monticelli L., Lao C., Crotty S. (2011) ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity 34, 932–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumjohann D., Okada T., Ansel K. M. (2011) Cutting edge: distinct waves of BCL6 expression during T follicular helper cell development. J. Immunol. 187, 2089–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita R., Schmitt N., Bentebibel S. E., Ranganathan R., Bourdery L., Zurawski G., Foucat E., Dullaers M., Oh S., Sabzghabaei N., Lavecchio E. M., Punaro M., Pascual V., Banchereau J., Ueno H. (2011) Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 34, 108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Coz C., Joublin A., Pasquali J.-L., Korganow A.-S., Dumortier H., Monneaux F. (2013) Circulating TFH subset distribution is strongly affected in lupus patients with an active disease. PLoS One 8, e75319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arroyo-Villa I., Bautista-Caro M.-B., Balsa A., Aguado-Acín P., Bonilla-Hernán M.-G., Plasencia C., Villalba A., Nuño L., Puig-Kröger A., Martín-Mola E., Miranda-Carús M. E. (2014) Constitutively altered frequencies of circulating follicullar helper T cell counterparts and their subsets in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amé-Thomas P., Hoeller S., Artchounin C., Misiak J., Braza M. S., Jean R., Le Priol J., Monvoisin C., Martin N., Gaulard P., Tarte K. (2015) CD10 delineates a subset of human IL-4 producing follicular helper T cells involved in the survival of follicular lymphoma B cells. Blood 125, 2381–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha Z., Zang Y., Guo H., Rechlic J. R., Olasnova L. M., Gu H., Tu X., Song H., Qian B. (2013) Association of peripheral CD4+ CXCR5+ T cells with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Tumour Biol. 34, 3579–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cha Z., Guo H., Tu X., Zang Y., Gu H., Song H., Qian B. (2014) Alterations of circulating follicular helper T cells and interleukin 21 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Tumour Biol. 35, 7541–7546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamekura R., Shigehara K., Miyajima S., Jitsukawa S., Kawata K., Yamashita K., Nagaya T., Kumagai A., Sato A., Matsumiya H., Ogasawara N., Seki N., Takano K., Kokai Y., Takahashi H., Himi T., Ichimiya S. (2015) Alteration of circulating type 2 follicular helper T cells and regulatory B cells underlies the comorbid association of allergic rhinitis with bronchial asthma. Clin. Immunol. 158, 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueno H., Banchereau J., Vinuesa C. G. (2015) Pathophysiology of T follicular helper cells in humans and mice. Nat. Immunol. 16, 142–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harker J. A., Lewis G. M., Mack L., Zuniga E. I. (2011) Late interleukin-6 escalates T follicular helper cell responses and controls a chronic viral infection. Science 334, 825–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopf M., Herren S., Wiles M. V., Pepys M. B., Kosco-Vilbois M. H. (1998) Interleukin 6 influences germinal center development and antibody production via a contribution of C3 complement component. J. Exp. Med. 188, 1895–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dienz O., Eaton S. M., Bond J. P., Neveu W., Moquin D., Noubade R., Briso E. M., Charland C., Leonard W. J., Ciliberto G., Teuscher C., Haynes L., Rincon M. (2009) The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakarov S., Fazilleau N. (2014) Monocyte-derived dendritic cells promote T follicular helper cell differentiation. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 590–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavele K.-M., Merry E., Ehrenstein M. R. (2015) Cutting edge: circulating plasmablasts induce the differentiation of human T follicular helper cells via IL-6 production. J. Immunol. 194, 2482–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt N., Bustamante J., Bourdery L., Bentebibel S. E., Boisson-Dupuis S., Hamlin F., Tran M. V., Blankenship D., Pascual V., Savino D. A., Banchereau J., Casanova J. L., Ueno H. (2013) IL-12 receptor β1 deficiency alters in vivo T follicular helper cell response in humans. Blood 121, 3375–3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma C. S., Suryani S., Avery D. T., Chan A., Nanan R., Santner-Nanan B., Deenick E. K., Tangye S. G. (2009) Early commitment of naïve human CD4(+) T cells to the T follicular helper (T(FH)) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol. Cell Biol. 87, 590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayamada S., Kanno Y., Takahashi H., Jankovic D., Lu K. T., Johnson T. A., Sun H. W., Vahedi G., Hakim O., Handon R., Schwartzberg P. L., Hager G. L., O’Shea J. J. (2011) Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity 35, 919–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coomes S. M., Pelly V. S., Kannan Y., Okoye I. S., Czieso S., Entwistle L. J., Perez-Lloret J., Nikolov N., Potocnik A. J., Biró J., Langhorne J., Wilson M. S. (2015) IFNγ and IL-12 restrict Th2 responses during helminth/plasmodium co-infection and promote IFNγ from Th2 cells. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattner F., Magram J., Ferrante J., Launois P., Di Padova K., Behin R., Gately M. K., Louis J. A., Alber G. (1996) Genetically resistant mice lacking interleukin-12 are susceptible to infection with Leishmania major and mount a polarized Th2 cell response. Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer A., Debuisson D., Denanglaire S., Eddahri F., Fievez L., Hercor M., Triffaux E., Moser M., Bureau F., Leo O., Andris F. (2014) Antigen presenting cell-derived IL-6 restricts Th2-cell differentiation. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 3252–3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eddahri F., Oldenhove G., Denanglaire S., Urbain J., Leo O., Andris F. (2006) CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control the magnitude of T-dependent humoral immune responses to exogenous antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda K., Kaisho T., Yoshida N., Takeda J., Kishimoto T., Akira S. (1998) Stat3 activation is responsible for IL-6-dependent T cell proliferation through preventing apoptosis: generation and characterization of T cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 161, 4652–4660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crotty S. (2012) The 1-1-1 fallacy. Immunol. Rev. 247, 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi H., Chen X., Chu C., Lu P., Xu H., Yan J. (2014) Follicular T-helper cells: controlled localization and cellular interactions. Immunol. Cell Biol. 92, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crotty S. (2014) T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 41, 529–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nish S. A., Schenten D., Wunderlich F. T., Pope S. D., Gao Y., Hoshi N., Yu S., Yan X., Lee H. K., Pasman L., Brodsky I., Yordy B., Zhao H., Brüning J., Medzhitov R. (2014) T cell-intrinsic role of IL-6 signaling in primary and memory responses. eLife 3, e01949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y. S., Eto D., Yang J. A., Lao C., Crotty S. (2013) Cutting edge: STAT1 is required for IL-6-mediated Bcl6 induction for early follicular helper cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 190, 3049–3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurieva R. I., Chung Y., Hwang D., Yang X. O., Kang H. S., Ma L., Wang Y. H., Watowich S. S., Jetten A. M., Tian Q., Dong C. (2008) Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity 29, 138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eddahri F., Denanglaire S., Bureau F., Spolski R., Leonard W. J., Leo O., Andris F. (2009) Interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling regulates the ability of naive T cells to acquire B-cell help capacities. Blood 113, 2426–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y., El Shikh M. E. M., El Sayed R. M., Best A. M., Szakal A. K., Tew J. G. (2009) IL-6 produced by immune complex-activated follicular dendritic cells promotes germinal center reactions, IgG responses and somatic hypermutation. Int. Immunol. 21, 745–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poholek A. C., Hansen K., Hernandez S. G., Eto D., Chandele A., Weinstein J. S., Dong X., Odegard J. M., Kaech S. M., Dent A. L., Crotty S., Craft J. (2010) In vivo regulation of Bcl6 and T follicular helper cell development. J. Immunol. 185, 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith K. A., Maizels R. M. (2014) IL-6 controls susceptibility to helminth infection by impeding Th2 responsiveness and altering the Treg phenotype in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu H., Xu L.-L., Teuscher P., Liu H., Kaplan M. H., Dent A. L. (2015) An inhibitory role for the transcription factor Stat3 in controlling IL-4 and Bcl6 expression in follicular helper T cells. J. Immunol. 195, 2080–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusam S., Toney L. M., Sato H., Dent A. L. (2003) Inhibition of Th2 differentiation and GATA-3 expression by BCL-6. J. Immunol. 170, 2435–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawant D. V., Sehra S., Nguyen E. T., Jadhav R., Englert K., Shinnakasu R., Hangoc G., Broxmeyer H. E., Nakayama T., Perumal N. B., Kaplan M. H., Dent A. L. (2012) Bcl6 controls the Th2 inflammatory activity of regulatory T cells by repressing Gata3 function. J. Immunol. 189, 4759–4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mari N., Hercor M., Denanglaire S., Leo O., Andris F. (2013) The capacity of Th2 lymphocytes to deliver B-cell help requires expression of the transcription factor STAT3. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 1489–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suto A., Nakajima H., Hirose K., Suzuki K., Kagami S., Seto Y., Hoshimoto A., Saito Y., Foster D. C., Iwamoto I. (2002) Interleukin 21 prevents antigen-induced IgE production by inhibiting germ line C(epsilon) transcription of IL-4-stimulated B cells. Blood 100, 4565–4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozaki K., Spolski R., Feng C. G., Qi C.-F., Cheng J., Sher A., Morse H. C. III, Liu C., Schwartzberg P. L., Leonard W. J. (2002) A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production. Science 298, 1630–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]