LysoPCs elicit Hck translocation, causing nPKC (PKCδ) to activate cPKC (PKCγ), which results in priming of neutrophil NADPH oxidase.

Keywords: lipid rafts, acute lung injury, WAVE

Abstract

Lysophosphatidylcholines (lysoPCs) are effective polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) priming agents implicated in transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). LysoPCs cause ligation of the G2A receptor, cytosolic Ca2+ flux, and activation of Hck. We hypothesize that lysoPCs induce Hck-dependent activation of protein kinase C (PKC), resulting in phosphorylation and membrane translocation of 47 kDa phagocyte oxidase protein (p47phox). PMNs, human or murine, were primed with lysoPCs and were smeared onto slides and examined by digital microscopy or separated into subcellular fractions or whole-cell lysates. Proteins were immunoprecipitated or separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted for proteins of interest. Wild-type (WT) and PKCγ knockout (KO) mice were used in a 2-event model of TRALI. LysoPCs induced Hck coprecipitation with PKCδ and PKCγ and the PKCδ:PKCγ complex also had a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)+ interaction with lipid rafts and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family verprolin-homologous protein 2 (WAVE2). PKCγ then coprecipitated with p47phox. Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation (IP), specific inhibitors, intracellular depletion of PKC isoforms, and PMNs from PKCγ KO mice demonstrated that Hck elicited activation/Tyr phosphorylation (Tyr311 and Tyr525) of PKCδ, which became Thr phosphorylated (Thr507). Activated PKCδ then caused activation of PKCγ, both by Tyr phosphorylation (Τyr514) and Ser phosphorylation, which induced phosphorylation and membrane translocation of p47phox. In PKCγ KO PMNs, lysoPCs induced Hck translocation but did not evidence a FRET+ interaction between PKCδ and PKCγ nor prime PMNs. In WT mice, lysoPCs served as the second event in a 2-event in vivo model of TRALI but did not induce TRALI in PKCγ KO mice. We conclude that lysoPCs prime PMNs through Hck-dependent activation of PKCδ, which stimulates PKCγ, resulting in translocation of phosphorylated p47phox.

Introduction

PMNs are critical in host defense against microbial invaders and exert their major microbicidal function in the tissues [1]. PMNs emigrate to the tissues in an orderly fashion, including selectin-mediated loose attachment or rolling, β2-integrin-mediated firm adhesion, and diapedesis through the endothelial layer, which involves platelet endothelial adhesion molecule [2–5]. Priming is an endogenous part of PMN function and changes the PMN phenotype from nonadherent to adherent and also augments release of the components of the microbicidal arsenal, both oxidative and nonoxidative, to a subsequent stimulus [6–8]. Priming agents also cause phosphorylation and translocation of specific cytosolic oxidase components: p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, Rac-2, p29phox (perioxiredoxin-6), to the membrane; however, they do not cause oxidase assembly/activation [7, 9–13]. Lastly, priming agents render the PMN functionally hyper-reactive, such that stimuli that do not induce activation of the NADPH oxidase and release of the nonoxidative components of the microbicidal arsenal in quiescent cells readily cause activation of primed cells [6, 14, 15]. In short, primed PMNs may be activated by a priming agent [14, 15].

LysoPCs are effective priming agents and are ligands for the G2A receptor, present on the PMN membrane [13, 16]. LysoPCs are mostly found as a mixture of compounds in plasma and have been implicated in TRALI, which is PMN-mediated with a 2-event pathogenesis [13, 17–19]. LysoPCs accumulate during the storage of cellular blood components, platelet concentrates, and unmodified RBC units and can cause the second event in TRALI, which is the activation of sequestered PMNs in the pulmonary microvasculature, resulting in endothelial cell damage, capillary leak, and ALI [20–23]. In addition, infusion of lysoPCs into mice with bacterial pneumonia increases survival and aids in the eradication of the bacterial pathogens [24].

LysoPCs induce rapid priming of neutrophils and cause Ser phosphorylation of p47phox and its translocation from the cytosol to the PMN membrane [13, 16]. Moreover, lysoPCs induce ligation of the G2A receptor and cause coprecipitation of G2A with clathrin and β-arrestin-1 [16]. Simultaneously lysoPCs elicit release of 2 separate G-protein subunits, Gαi and Gαq11, which cause a rapid increase in cytosolic Ca2+ [16]. The Gβγ subunits, which are released from Gαi and Gαq11, cause activation of the Src family kinase Hck, although little is known with regard to the intracellular events that result in lysoPC-induced Ser phosphorylation of and translocation of p47phox [16]. We hypothesize that lysoPCs induce Hck-dependent activation of PKC, resulting in phosphorylation of p47phox and translocation to the PMN membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals, unless otherwise indicated, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All solutions were made from sterile water, USP, purchased along with sterile 0.9% saline, USP, from Baxter Healthcare (Deerfield, NY, USA), with buffers that are pyrogen free for human intravenous administration [13, 25]. All solutions were sterile filtered with Nalgene MF75 series disposable sterilization filter units (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The Ficoll-Paque PLUS and the ECL Detection kit were purchased from GE Life Sciences (Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and the BCA Protein Assay Kit was from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Nitrocellulose membranes were obtained from Life Science Products (Frederick, CO, USA). Gö6983 and Rottlerin were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). A Leica DRM mechanized fluorescence microscope, equipped with a movable stage with a custom Zeiss 63× water-immersion lens, was purchased from Leica Microsystems (Exton, PA, USA). Four epifluorescence cubes [FITC, Cy-3, Cy-5, and AMCA (aminomethylcoumarin)] were obtained from Chroma Technology (Bellows Falls, VT, USA). A cooled CCD camera and SlideBook software for computer operation were purchased from The Cooke Corp. (Auburn Hills, MI, USA) and Intelligent Imaging Innovations (Denver, CO, USA), respectively [26]. Sotrastaurin (AEB071) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Antibodies to the PKC isoenzymes and other proteins were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA): clones C-20 and H-7 for PKCα; clones C-16 and E-3 for PKCβI; clones C-18 and F-7 for PKCβII; clones C-19 and N-16 for PKCγ; clones C-20 and G-9 for PKCδ; clones T507, Y525, Y52, and Y311 for pPKCδ; clones G-4 and H-85 for Hck; and clone Y411 for pHck. In addition, antibodies to PKC isoenzymes were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), including clones aa 302–322 and aa 681–687 for PKCγ; clones T514, T655, and T674 for pPKCγ; clone aa 577–677 for PKCδ; and clones S664 and 645 for pPKCδ. Antibodies to pPKCγ clone T514 and pPKCδ clone T505 and the secondary antibody of goat anti-rabbit were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA), along with molecular weight markers. Recombinant proteins were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences and United States Biological (Salem, MA, USA). The WT and PKCγ KO mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). A lipid rafts labeling kit was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

LysoPC preparation

LysoPCs were solubilized in 1.25%, essentially fatty acid- and globulin-free human albumin and consisted of 1-o-palmitoyl:0.8 mM, 1-o-oleoyl:0.3 mM, 1-o-stearoyl:0.3 mM, and 1-o-hexadecyl (C16) lysoPAF:0.003 mM stock, as published [13].

PMN isolation

PMNs were isolated from whole blood drawn from healthy donors under a protocol approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board at the University of Colorado Denver and used standard techniques: Dextran sedimentation, Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation, and hypotonic lysis of contaminating RBCs [20]. Cells were resuspended (2.5 × 107 cells/ml) in Krebs-Ringer phosphate with 2% dextrose, pH 7.35.

Real-time PCR for PKCγ

Total RNA was isolated from PMNs from 2 healthy donors using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and was quantified spectrophotometrically and compared with total RNA from cultured human SAECs (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA). In brief, 1 μg total RNA was used to prepare cDNA using the qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed on an iQ5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). All primer-probe gene-expression assays for real-time analyses were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (PKCγ Assay ID Hs00177010_m1, GAPDH Assay ID Hs99999905_m1). Total cDNA (2 μl) was used to assay PKCγ transcripts, and 1 μl 1:10 dilution of the cDNA was to assay for GAPDH as a housekeeping control. All products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel for further validation.

PMN subcellular fractions

Isolated PMNs (1 × 108 cells/ml) were stimulated with 4.5 or 14.5 μM lysoPCs for 0.5–5 min. The reaction was stopped with an equal volume of relaxation buffer (3.5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM NaCl, and 10 mM PIPES, pH 7.4) and then sonicated 3 times for 30 s. The lysate was centrifuged to get the postnuclear supernatant, which was loaded onto a 15–60% sucrose gradient. The gradient was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4°C. The cytosol, membrane, and granular fractions were removed, protein concentration determined by BCA, and the proteins separated by 10% SDS-PAGE with each fraction from the same number of cellular equivalents [26]. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked in BSA, and immunoblotted [26]. The subcellular fractions were immunoprecipitated for the proteins of interest [26]. To control for possible nonspecificity of the antibodies used, IPs were completed for PKCγ and PKCδ and the proteins separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and probed with multiple antibodies to PKCα, -βI, -βII, -γ, and -δ. The PKCγ IP did not demonstrate immunoreactivity with any of the other antibodies to PKC isoenzymes, and identical experiments were performed for IPs of PKCδ, which yielded identical results (Supplemental Fig. 1). When IPs were performed, they were reversed so that the protein that was probed in the IP was then immunoprecipitated, and the other protein that colocalized was probed in this IP.

PKC activity assay in PMN subcellular fractions

PKC activity kits were purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). These assays were performed on subcellular fractions in triplicate, per the manufacturer’s instructions. These assays use 96-well plates coated with a PKC pseudosubstrate. The phosphorylated pseudosubstrate is recognized by a biotinylated antibody. An HRP-labeled streptavidin detects the biotin and is quantified at 492 nm.

Digital microscopy

Isolated PMNs were incubated with albumin or lysoPCs (1.45–14.5 μM) for 1–10 min, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, smeared onto slides, washed, porated, and incubated with a primary antibody or a primary-labeled antibody, WGA, and bis-benzimide [26]. In cases where the unlabeled primary antibody was used, slides were also incubated with a labeled secondary [27]. Lipid rafts were identified by labeling with Alexa 555 CTB [28].

The PMNs were imaged at 100× (Zeiss NA1.4, working depth 2.2 μm), and the data from 3 epifluorescence channels were digitized on a cooled CCD camera at 1280 × 1024 pixels with 12-bit fidelity [26]. To ensure that the fluorescent intensity data were not saturated, the cell body and the cell membrane were selected by threshold masking on the WGA intensity and by subselection of the highest intensity edge, respectively. The individual cells were counted (submasking), each by total area and membrane area [26]. In each region, area (cellular footprint), mean intensities, and total intensities were calculated for each channel. The data for the 2 regions of interest (7 × 2) in each cell (30 PMNs/group) were loaded onto StatView software (4.5; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and analyzed by ANOVA. Translocation was derived from the total immunoreactivity intensity in the membrane relative to the total cellular intensity. Selection of the regions of interest with the intensity of WGA staining for sialo-membranes (FITC channel) removed bias in assessing the integrated intensity contained in those regions (Cy-3) [26].

PMN isolation from mice

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado Denver. WT and PKCγ KO mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and blood removed via cardiac puncture and loaded onto Histopaque gradient for separation at 700 g, 20 min. Hypotonic lysis removed RBCs, and the PMNs were resuspended at 2.5 × 107 cells/ml [29].

In vitro activation of PKC

Isolated human PMNs warmed to 37°C for 3 min; an equal volume of relaxation buffer added; the PMNs sonicated in 3, 30 s pulses, centrifuged at 2500 g for 10 min at 4°C; and the supernatant saved. After a BCA analysis was done, 25 μg protein was immunoprecipitated for PKCγ, PKCδ, or Hck overnight at 4°C. After incubation with protein A/G beads to pull down the protein, the beads were pelleted, and the immunodepleted supernatant was removed. Fifty percent (v:v) of the supernatant was used for activation assays with recombinant proteins, with active recombinant proteins added to the immunodepleted supernatant: 240 (PKCγ), 302 (PKCδ), or 196 mU (Hck), and brought to a final volume with 1× kinase reaction buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After addition of the active protein, the reaction was stopped with 4× SDS digestion buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-antibodies.

A murine model of ALI

An in vivo murine model of ALI, identical to our rat model, was completed [19]. WT and PKCγ KO mice were weighed, injected intraperitoneally with NS or LPS (Salmonella enteritides, 2 mg/kg), and incubated (2 h). Mice were anesthetized, the tail vein cannulated, and blood withdrawn, 10% of total blood volume [body weight (kg) × 70]. Mice were infused with NS or 4.5 μM lysoPCs (4 ml/h), followed by EBD (30 mg/kg), and incubated (6 h). Mice were reanesthetized, blood was drawn via cardiac puncture, and the mice were euthanized, followed by a BAL [19]. The blood and BALF were centrifuged and supernatants stored at −80°C. ALI was determined as the percentage of EBD leak from the plasma into BALF [19].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the means ± sem and were analyzed with independent or repeated-measures ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni or Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons, based on the equality of variance.

RESULTS

LysoPCs cause activation of PKC and translocation of PKCγ and PKCδ

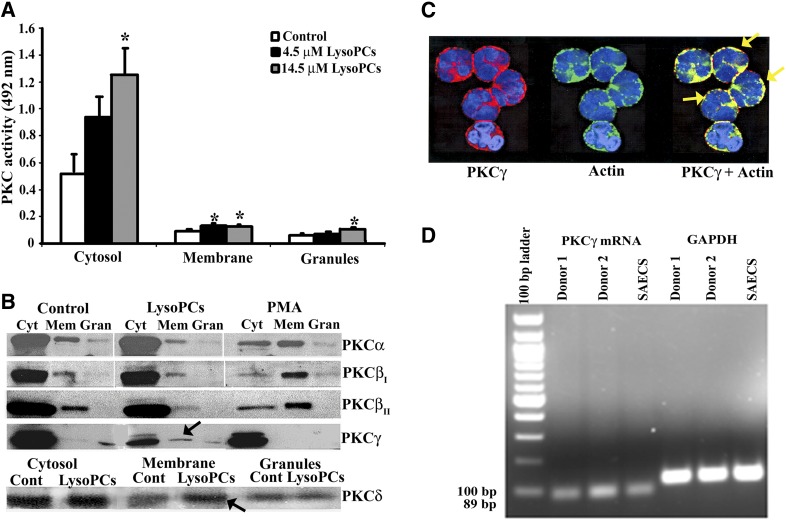

LysoPCs rapidly caused an increase in general PKC activity in the PMN membrane at concentrations of 4.5 and 14.5 μM, with the higher concentration resulting in increased PKC activity in both the cytosolic and granule fractions (Fig. 1A). The translocation of specific PKC isozymes was investigated, using antibodies to both cPKC (Ca2+ dependent)—PKCα, PKCβI, PKCβII, and PKCγ—and a nPKC (Ca2+ independent)—PKCδ (Fig. 1B). To ensure specificity of the observed immunoreactivity, divergent antibodies were used from different vendors, and positive controls were used for each PKC isozyme. The data demonstrated identical results for the different antibodies to each PKC isozyme, and the positive controls were only recognized by antibodies specific for this protein (data not shown). As a further control, when the recognized polypeptide sequence was available, it was added with the primary antibody to ensure that the immunoreactivity was specific for each PKC (data not shown). In albumin-treated controls, PKCα is mainly in the cytosol, with modest immunoreactivity present in the membrane and trace amounts in the granules (Fig. 1B). The patterns for lysoPCs were similar to controls; however, PMA induced increased PKCα in the membrane with relatively less in the cytosol, indicative of membrane translocation with trace amounts in the granule fraction. The same trend is seen with PKCβI and PKCβII, such that PMA caused membrane translocation of both of these PKC isozymes, whereas albumin and lysoPCs did not. In contrast, lysoPCs caused translocation of both PKCγ and PKCδ to the membrane with less immunoreactivity in the cytosol versus both albumin and PMA (Fig. 1B, black arrows). In short, lysoPCs (4.5 μM) caused membrane translocation of PKCγ and PKCδ (Fig. 1B). PKCγ translocation was confirmed by digital microscopy, which demonstrated lysoPC-mediated colocalization with actin at the PMN membrane (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. LysoPCs activate PKC in PMNs, specifically PKCγ and PKCδ, and PMNs contain mRNA for PKCγ.

(A) Isolated PMNs were stimulated with vehicle (albumin; white bars), 4.5 μM lysoPCs (black bars), or 14.5 μM lysoPCs (gray bars) for 1 min and separated into subcellular fractions. PKC activity was determined in the subcellular fractions by a commercial ELISA. Both 4.5 and 14.5 μM lysoPCs induced a significant (*P < 0.05) increase in PKC activity in the membrane from control, and the 14.5 μM lysoPC concentration increased PKC activity in the membrane and granules as well (*P < 0.05, n = 5 for each group). (B) In albumin-treated controls (Cont) and lysoPC-primed PMNs, PKCα is mainly in the cytosol (Cyt), with modest immunoreactivity in the membrane (Mem) and trace amounts in the granules (Gran). In contrast, PMA induced increased PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII in the membrane with relatively less in the cytosol, indicative of membrane translocation, with trace amounts in the granule fraction. In contrast, lysoPCs caused translocation of both PKCγ and PKCδ to the membrane (black arrows) with less immunoreactivity in the cytosol versus both albumin and PMA. These blots are representative of separate experiments. (C) Isolated PMNs were stimulated with lysoPCs for 1 min, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, smeared onto slides, and incubated with antibodies to PKCγ (red) and actin (green). PKCγ and actin colocalize (yellow) at the periphery of PMNs (right; yellow arrows). This micrograph is representative of 3 separate experiments. Albumin-treated control PMNs did not demonstrate a colocalization of PKCγ with actin (results not shown). (D) Total RNA was isolated from PMNs from healthy donors. An 89 bp message specific for PKCγ is present in both donors and was virtually identical to the 89 bp message for PKCγ from SAECs, the positive control. The mRNA for GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. This figure is representative of 2 separate experiments.

As human PMNs have not been reported to contain PKCγ, total RNA was isolated from human PMNs. An 89 bp mRNA transcript specific for PKCγ was present in PMNs from 2 healthy donors and was at the same migration as the PKCγ mRNA transcript from SAECs, the positive control (Fig. 1D). GAPDH was used as a loading control (Fig. 1D).

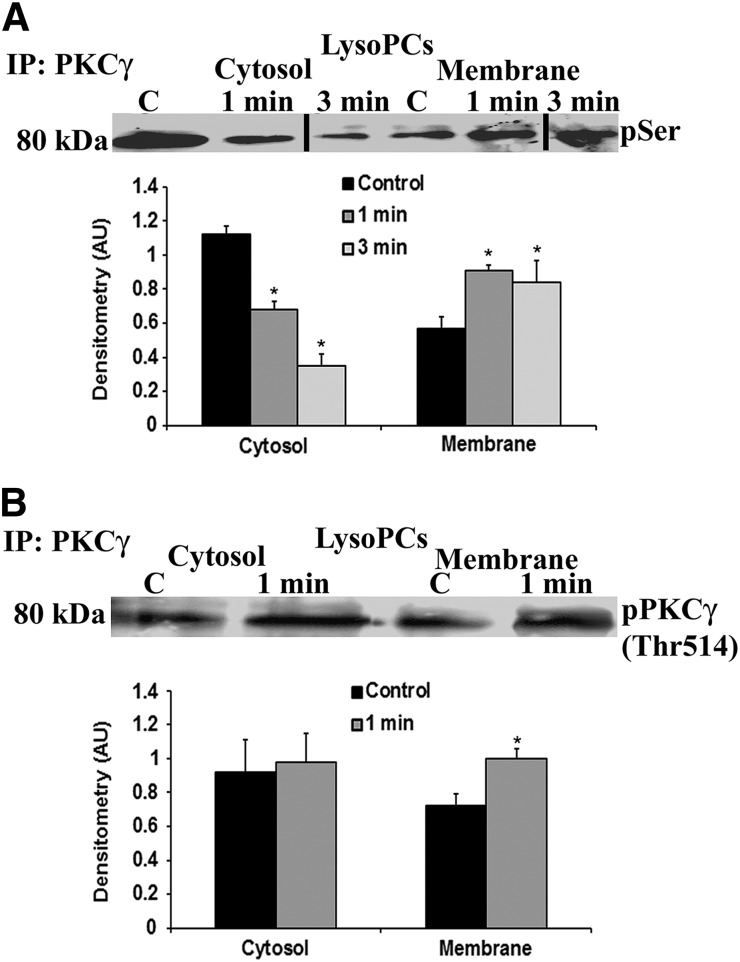

Activation of PKCγ and the association between PKCδ and PKCγ

As PKCγ requires Thr phosphorylation and Ser phosphorylation for activation, the membranes of lysoPCs primed with 4.5 μM lysoPCs for 1–5 min were immunoprecipitated for PKCγ and immunoblotted for phosphoserine or Thr pPKCγ (Tyr514; Fig. 2A and B) with a bar graph of the densitometry of the bands from 3 gels depicted below [30, 31]. LysoPCs vs. albumin-treated controls induced translocation of pPKCγ to the membrane at 1 min (Fig. 2B) and Ser-pPKCγ to the membrane at 1 and 3 min, with a bar graph of the densitometry included below (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. LysoPCs elicit membrane translocation of active pPKCγ.

(A) LysoPCs induced membrane translocation of PKCγ at 1 and 3 min. The membranes were stripped and demonstrated phosphoserine (pSer) immunoreactivity of the identical bands at 80 kDa. The bar graph represents the densitometry of 3 separate experiments [*P < 0.05 vs. albumin control (C), n = 4]. (B) LysoPC (4.5 μM)-primed PMNs evidenced increased membrane immunoreactivity of pPKCγ (Thr514) at 1 min. The bar graph is the densitometry of the immunoreactivity, which demonstrated a significant increase in lysoPC induced immunoreactivity in the membrane (*P < 0.05 vs. albumin control, n = 4).

As compared with albumin-treated controls, lysoPCs (4.5 μM) induced coprecipitation of PKCγ with PKCδ at the membrane (Fig. 3Ai), with a bar graph of the densitometry from 3 different experiments included below. lysoPCs also induced the pPKCδ to coprecipitate with PKCγ at the membrane [both Tyr (Tyr311 and Tyr525; Fig. 3Aii and iii) and Thr (Thr514) pPKCδ]; note the bar graphs of the densitometry below (Fig. 3Aiv). Importantly, pPKCδ (Tyr525) is the human equivalent of rodent Tyr pPKCδ (Tyr523). The lysoPC-mediated interaction of pPKCδ (Tyr525) with lipid rafts was confirmed by digital microscopy using fluorescently labeled CTB for imaging of lipid rafts (Fig. 3B) [28]. Identical data demonstrated that pPKCγ (Tyr514) also colocalized with lipid rafts, and IP of PKCδ from lysoPC-primed PMNs demonstrated coprecipitation of PKCγ (results not shown). Taken as a whole, both the IPs and digital microscopy demonstrated that lysoPCs caused translocation of pPKCδ and pPKCγ to the plasma membrane in a physical relationship with one another.

Figure 3. LysoPCs caused coprecipitation of PKCδ with PKCγ at the PMN membrane and a FRET+ interaction among PKCγ, PKCδ, and lipid rafts.

(Ai) LysoPCs (4.5 μM) induced coprecipitation of PKCδ with PKCγ in the membrane at 1 min. Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed for specific Tyr pPKCδs: Tyr311 and Tyr525 (ii and iii, respectively), or Thr pPKCδ: Thr507 (iv), and demonstrated that lysoPCs induced membrane translocation of active, specific Tyr and Thr/Ser pPKCδ. The bar graphs are the densitometry of the immunoblots and demonstrate a significant lysoPC-elicited increase in the immunoreactivity in the membranes (*P < 0.05 vs. albumin control, n = 4). (B) Digital microscopy demonstrated that lysoPC versus albumin-treated PMNs induced a physical FRET+ relationship (FRETc, FRET channel) between PKCδ (green) and lipid rafts (red) with maximal FRET+ intensity in the periphery, as demonstrated in pseudocolor (lower right). The red FRET+ interaction, which appears to be in the middle, is typical in PMNs because of the membrane ruffling that priming imparts. These data are representative of 4 separate experiments.

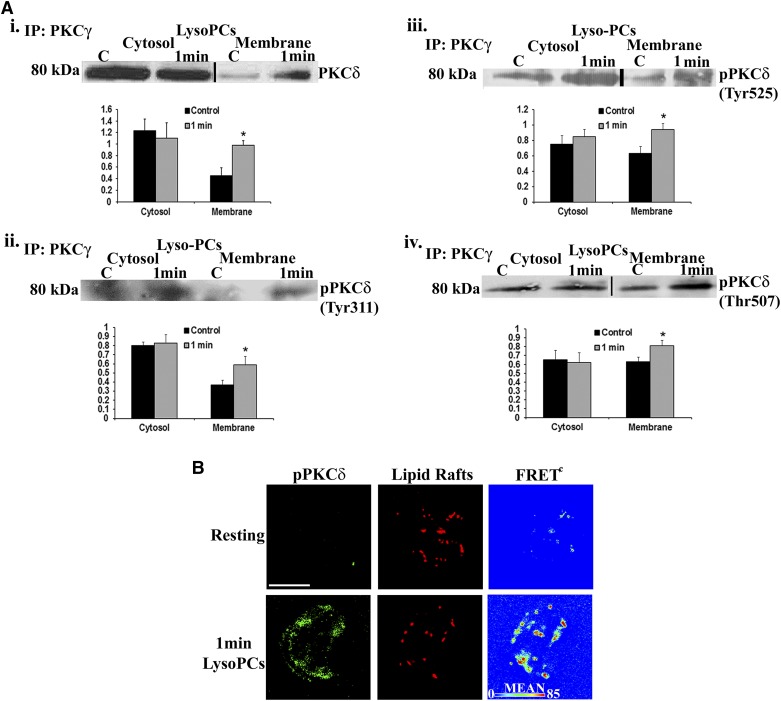

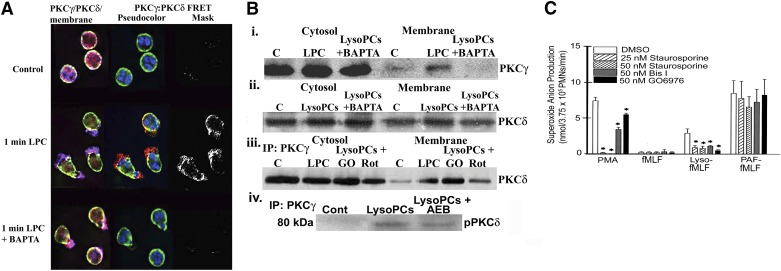

The dependence of PKCγ on PKCδ

To explore further the physical relationship of PKCδ and PKCγ, isolated PMNs were pretreated with 1 mM BAPTA-AM, or DMSO control to chelate intracellular Ca2+. Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ abrogated the FRET+ interaction between PKCγ and PKCδ (Fig. 4A), inhibited lysoPC-induced translocation of PKCγ to the membrane (Fig. 4Bi), but only partially attenuated membrane translocation of PKCδ (Fig. 4Bii). When PMNs were pretreated with DMSO (vehicle); Gö6983, a cPKC inhibitor (50 nM); Rottlerin, a nonspecific PKC antagonist (10 μM) that may inhibit PKCδ; or AEB071, a pan-PKC inhibitor that at 2 nM, will inhibit PKCδ (2 nM) but not PKCγ, both Rottlerin (10 μM) and AEB071 decreased the coprecipitation of PKCδ with PKCγ in the membrane, whereas Gö6983 had no effect (Fig. 4Biii and iv) [32–34]. Rottlerin pretreatment (10 μM) also inhibited lysoPC priming of the fMLF-activated oxidase by 100 ± 8% (P < 0.05, n = 5). Taken as a whole, the inhibitor data implicated PKCδ in the activation of PKCγ and lysoPC priming of PMNs. In addition, isolated PMNs were pretreated with other PKC inhibitors: staurosporine (25–50 nM), Bis I (50 nM), and Gö6976 (50 nM). In PMNs primed with lysoPCs and followed by fMLF activation, the PKC inhibitors significantly inhibited the oxidase response compared with DMSO controls (Fig. 4C). These data reinforce that PKCδ and PKCγ activity is required for lysoPC priming.

Figure 4. Ca2+ chelation and PKC inhibitors differentially affect lysoPC priming.

(A) Isolated PMNs were pretreated with DMSO or BAPTA-AM; primed with albumin or 4.5 μM lysoPCs; and examined by digital microscopy. The left column illustrates the colocalization of the immunoreactivities of PKCγ (blue) and PKCδ (red). The middle column demonstrates the membrane stained with WGA (green), a bis-benzimide chromatin stain (blue) to identify the nuclei, and FRET+ by pseudocolor, with red being the most intense. Albumin- treated controls contained both PKCγ and PKCδ immunoreactivities that did not have a physical relationship (top). However, lysoPCs induced a colocalization and FRET+ interaction, demonstrating an intense purple color (left column) and a yellow-red pseudocolor (middle column) between PKCγ and PKCδ, which is best visualized in the positive FRET (middle row). Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ decreased the colocalization of PKCγ with PKCδ (left column) and abrogated the FRET+ interaction of PKCγ with PKCδ (middle and right columns) but did not inhibit the translocation of PKCδ to the membrane (bottom row). LPC, lysoPC. (B) Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM inhibited membrane translocation of PKCγ immunoreactivity (i) but not PKCδ (ii). Inhibition of PKCδ with Rottlerin (Rot) but not Gö6976 (GO), a cPKC inhibitor, decreased the coprecipitation of PKCδ with PKCγ (iii). Pretreatment of PMNs with AEB071 (AEB; 2 nM), an inhibitor of PKCδ, also decreased the coprecipitation of PKCδ with PKCγ (iv). (C) PKC inhibitors staurosporine (25 and 50 nM), Bis I, and Gö6976 were able to inhibit variably PMA activation of the PMN oxidase and to abrogate almost totally lysoPC priming of the fMLF-activated respiratory burst without affecting fMLF activation or PAF priming of the fMLF-activated oxidase (*P < 0.05 vs. DMSO controls, n = 5). The microscopy and Western blots are representative of 4 disparate experiments.

Hck activates PKCδ, which activates PKCγ

LysoPCs, via the GPCR G2A, phosphorylate Hck, a Src family tyrosine kinase [16]. Digital microscopy of lysoPC-primed PMNs demonstrated that lysoPCs elicited a FRET+ physical association of pPKCγ with pHck (Tyr411) and pPKCδ with pHck, and an overlay of these two FRETs demonstrated colocalization (Fig. 5A). Therefore, lysoPCs elicited a complex containing all 3 kinases: pHck, pPKCδ, and pPKCγ. Pretreatment of PMNs with PP2, an Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibited pPKCγ and pPKCδ (Fig. 5Bi). Hck was immunoprecipitated from PMNs primed with lysoPCs (0.5–5 m) and immunoblotted for PKCδ, and the converse was also completed. LysoPCs induced coprecipitation of Hck with PKCδ from 1 to 5 m (Fig. 5Ci). PKCγ and PKCδ were also immunoprecipitated from PMNs and immunoblotted with WAVE2 and both PKCs coprecipitated with WAVE2 (Fig. 5Ciii and iv). Furthermore, pretreatment of PMNs with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein inhibited lysoPC priming of the fMLF-activated respiratory burst by 78 ± 7% (P < 0.05, n = 6 vs. the DMSO vehicle) [35].

Figure 5. Hck activates the PKCδ/PKCγ complex.

(A) PMNs were primed with albumin or with 4.5 μM lysoPCs and examined by digital microscopy using fluorescently labeled antibodies to pPKCγ (green), pHck (red), and pPKCδ (blue). In albumin-treated PMNs, there were minimal amounts of pPKCγ, pHck, and pPKCδ, which did not localize, nor did albumin induce FRET+ interactions among any of these proteins (top). LysoPC priming caused increased amounts versus albumin of intracellular pPKCγ (Thr514), pHck (Tyr411), and pPKCδ (Tyr525) immunoreactivity with colocalization of all 3 proteins (overlay; white color). LysoPCs also induced FRET+ interactions between pPKCγ and pHck (bottom left) and pPKCδ and pHck (bottom middle) and among all 3 proteins (bottom right). a.l.u.f.i., arbitrary linear units of fluorescence intensity. (B) LysoPCs caused pPKCδ (Thr525), which was partially inhibited by PP2, an Src kinase inhibitor (i). When the identical PMNs were immunoblotted for PKCγ, lysoPCs induced an increase in pPKCγ (Thr514), which was abrogated by PP2 pretreatment (ii). (C) LysoPCs induced colocalization of PKCδ with Hck (i) that initially appears at 30 s and is maximal at 5 min and active pHck (Tyr411), colocalized with PKCδ (ii). LysoPCs also caused colocalization of PKCγ and PKCδ with WAVE2 (iii and iv, respectively). The digital microscopy and immunoblots are representative of at least 4 separate experiments.

As lysoPC priming of PMNs results in the translocation and physical interaction of Hck, PKCδ, and PKCγ at the membrane, PMN cellular extracts were immunodepleted of the desired protein, an active recombinant kinase was added back, and the extracts were probed for activated kinases that were presumed to be downstream of the active recombinant kinases. Active recombinant Hck was added to PMN extracts “immunodepleted” of Hck, and this addition resulted in pPKCδ at Tyr525 at 15 s (Fig. 6A) with subsequent pPKCγ (Thr514) at 60 s. In addition, when PKCδ-immunodepleted PMN extracts were given active PKCδ, there was an increase in pPKCγ (Thr514), beginning at 30 s, with maximal pPKCγ at 60 s, which persisted for 5 min (Fig. 6B). However, when PKCγ-immunodepleted PMNs were given active PKCγ, there was no increase in pPKCδ (Fig. 6C). These data provide evidence that Hck phosphorylates PKCδ, which in turn, phosphorylates PKCγ.

Figure 6. Recombinant protein activation of PKCγ and PKCδ.

The PMN lysates were immunodepleted (ID) of PKCγ, PKCδ, or Hck IP. The immunodepleted supernatant was then subjected to an activation assay, in which the depleted active recombinant protein was added back, treated with lysoPCs for 15 s–5 min, and separated and analyzed by Western blots. In Hck immunodepleted supernatants, the active recombinant Hck caused pPKCδ (Tyr525) at 15 s (A, upper) and pPKCγ (Thr514) at 60 s (A, lower). In PKCδ immunodepleted supernatants, active recombinant PKCδ induced pPKCγ (Thr514), which was present at 30 s–5 min and maximal at 60 s (B). In contrast, in PKCγ immunodepleted lysates, active PKCγ did not cause pPKCδ (C). This figure is representative of 3 separate experiments.

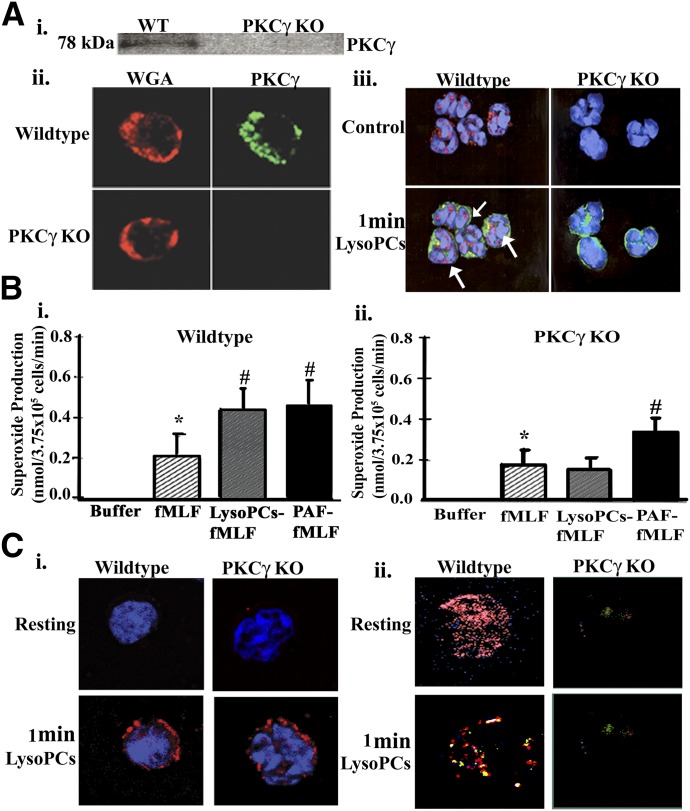

PKCγ KO mice

In isolated PMNs from both WT and PKCγ KO mice, no discernible PKCγ immunoreactivity was present in the KO mice compared with the WT, which was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 7Ai) and digital microscopy, in that both the PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice took up WGA in their membranes, and only the PMNs from WT mice had PKCγ immunoreactivity (Fig. 7Aii). When the PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice were treated for 1 min with lysoPCs, PKCγ (red) was translocated to the membrane (WGA, green) in the WT mouse PMNs, yielding a yellow color that was not present in the PKCγ KO mice (Fig. 7Aiii). As seen with human PMNs, lysoPCs significantly primed the fMLF-activated respiratory burst in PMNs from WT mice (P < 0.05, n = 5; Fig. 7Bi); however, in the PKCγ KO mice, lysoPCs did not prime the fMLF-activated respiratory burst, whereas PAF, the positive control, did (P < 0.05, n = 5; Fig. 7Bii). These data suggested that PKCγ is important in the lysoPC priming of the NADPH oxidase in murine PMNs. Furthermore, in the PMNs from both WT and PKCγ KO mice, lysoPCs elicited pHck translocation to the membrane (Fig. 7Ci). Moreover, in WT mouse PMNs, PKCγ is present (red), which overshadows the PKCδ (green), whereas in the PKCγ KO PMNs, there is only the faint green color of PKCδ (Fig. 7Cii, upper). LysoPCs induced colocalization (yellow) of PKCγ (red) and pPKCδ (green; Fig. 7Cii, lower left). No colocalization was visualized in the lysoPC-stimulated PMNs from PKCγ KO mice, which demonstrated only faint PKCδ immunoreactivity (green; Fig. 7Cii, lower right).

Figure 7. PKCγ detection in WT and PKCγ KO mice.

(Ai) There was no PKCγ present in the PMNs from the PKCγ KO mice, with PKCγ present in the WT mice. (ii) PMNs from both PKCγ KO and WT demonstrated that PKCγ immunoreactivity (green) was present in the WT mice PMNs (upper right) but not the PKCγ KO PMNs (lower right), and the membranes were stained with WGA (red; left). (iii) LysoPC (1 min) induced PKCγ translocation to the membrane with colocalization (yellow; white arrows; nuclei are stained blue with bis-benzimide), whereas the PKCγ KO mice had no PKCγ immunoreactivity. (B) PMN priming of the NADPH oxidase was measured in the isolated PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice. In the WT mice, fMLF caused significant activation of the PMN oxidase (striped bars), and both lysoPCs (gray bars) and PAF (black bars) significantly primed fMLF activation in the PMNs from WT mice (i). (ii) In the PMNs from PKCγ KO mice, fMLF also caused significant activation of the oxidase; however, lysoPCs did not prime and augment the fMLF-activated respiratory burst, but PAF did (*P < 0.05 vs. albumin-treated PMNs, #P < 0.05 vs. fMLF-activated PMNs, n = 5). (Ci) Isolated PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice were treated with albumin or 4.5 μM lysoPCs for 1 min, demonstrating Hck immunoreactivity (red). Identical PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice were treated with albumin (control) or lysoPC for 1 min, incubated with primary antibodies to PKCγ (red) or pPKCδ (green), and examined by digital microscopy (ii). There is PKCγ immunoreactivity in the PMNs from WT mice, which masks the PKCδ green immunoreactivity, and there is no PKCγ immunoreactivity with some PKCδ immunoreactivity (green) in the PMNs from the PKCγ KO mice. LysoPCs induced pPKCδ immunoreactivity (green) and colocalization of pPKCδ and PKCγ (yellow; lower left), but there is only pPKCδ immunoreactivity in lysoPC-primed PMNs from PKCγ KO mice (right). All figures are representative of 3 separate experiments.

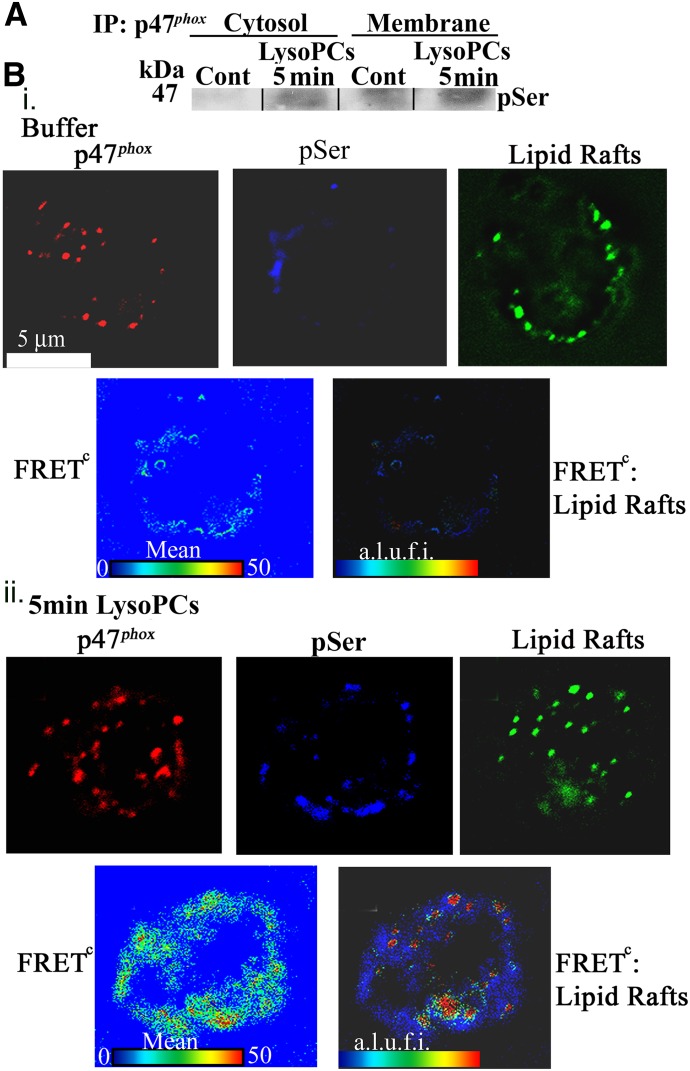

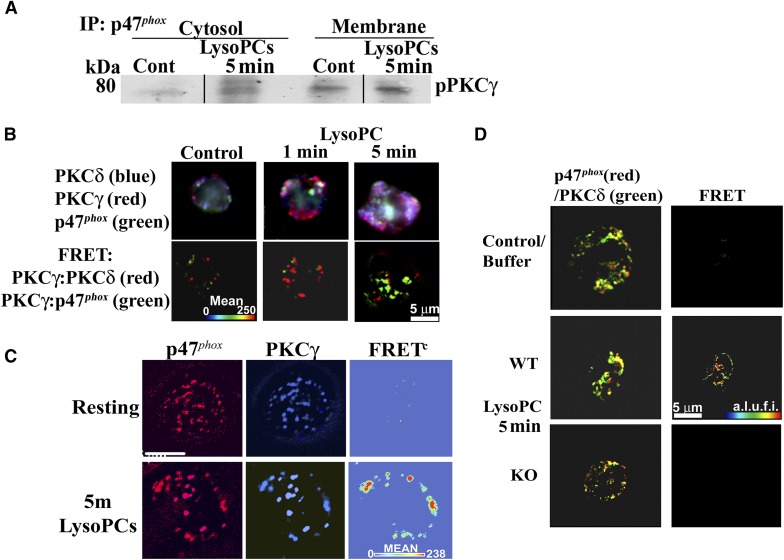

p47phox phosphorylation and translocation and PKCγ activation

LysoPCs caused the translocation of p47phox from the cytosol to the membrane at 5 min, and p47phox was phosphorylated on serine (Fig. 8A). These data were expanded by digital microscopy and demonstrated that lysoPCs, compared with albumin-treated PMNs, induced a FRET+ interaction of p47phox with phosphoserine at 5 min (Fig. 8Bi and ii, lower, blue panels), and the FRET between p47phox and phosphoserine demonstrated a FRET+ interaction at 5 min with lipid rafts, which are contiguous with the PMN membrane (Fig. 8B) [36, 37]. In addition, active, pPKCγ coprecipitated with p47phox at the PMN membrane at 5 min, providing evidence of direct pPKCγ of p47phox (Fig. 9A). To investigate the relationship further among PKCδ, PKCγ, and p47phox, a time course of the PKCδ and PKCγ interaction with p47phox was completed and demonstrated that the FRET+ interaction between PKCδ and PKCγ (green) was maximal at 1 min before the FRET+ interaction between PKCγ and p47phox (red), which occurs at 5 min (Fig. 9B) with minimal interactions between PKCδ and PKCγ and PKCγ and p47phox in albumin-treated controls (Fig. 9B). Further confirmation of the PKCγ:p47phox relationship is illustrated in Fig. 9C, demonstrating that lysoPCs induced a FRET+ interaction between and PKCγ and p47phox in the PMN membrane at 5 min, which is not present in control PMNs (Fig. 9C). In addition, in the PMNs from WT mice, lysoPCs elicited a FRET+ interaction between PKCδ and p47phox, which was not present in the albumin-treated controls nor in PMNs from the PKCγ KO mice (Fig. 9D). Importantly, there was obvious PKCδ immunoreactivity in WT and PKCγ KO animals and the lack of a FRET+ interaction in the PMNs from PKCγ KO mice confirms the need for PKCγ for lysoPC-mediated interactions among PKCδ, PKCγ, and p47phox (Fig. 9D).

Figure 8. LysoPC priming causes p47phox translocation to the membrane/lipid rafts.

(A) Isolated PMNs were treated with albumin or lysoPCs for 5 min, separated into the cytosolic and membrane fractions, immunoprecipitated for p47phox, and immunoblotted for phosphoserine. LysoPCs caused p47phox membrane translocation, demonstrated by immunoreactivity for phosphoserine compared with albumin-treated control PMNs, as well as an increase of phosphoserine in the cytosol. (Bi) PMNs were analyzed via digital microscopy using fluorescently labeled antibodies to p47phox (red), phosphoserine (blue), and lipid rafts (green). In albumin-treated PMNs, there is diffuse immunoreactivity for p47phox, with minimal cellular phosphoserine, and lipid rafts in the cellular periphery (upper). There is minimal cellular FRET positivity between p47phox and phosphoserine, as well as FRET positivity between the p47phox:phosphoserine FRET and lipid rafts (lower). (ii) In contrast, lysoPCs (5 min) caused increased cellular phosphoserine and elicited a FRET+ interaction between p47phox and phosphoserine with a positive FRET between the p47phox:phosphoserine FRET and lipid rafts. The data are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Figure 9. LysoPCs cause a physical interaction between p47phox and PKCγ, which is required for priming.

(A) Compared with albumin-treated controls, lysoPCs induced immunoreactivity for pPKCγ in the cytosol and translocation to the membrane. (B) Albumin-treated controls demonstrated immunoreactivity for PKCδ (blue), PKCγ (red), and p47phox (green; upper left) with only minimal FRET positivity (lower left). Following 1 and 5 min lysoPC priming, the immunoreactivities appear to become more intense and localize together in the PMN periphery (upper middle and right), and there is significant FRET positivity between PKCγ and PKCδ (red) and PKCγ and p47phox (green) at 1 min versus the albumin controls with more FRET positivity for PKCγ and PKCδ (red) than PKCγ and p47phox (green). At 5 min, lysoPCs induced more FRET positivity for PKCγ and p47phox (green) than for PKCγ and PKCδ (red). (C) LysoPCs induce a FRET+ interaction between PKCγ (blue) and p47phox (red) at 5 min versus albumin-treated (Resting) PMNs. In both resting (albumin-treated) PMNs and lysoPC-primed PMNs, there is positive immunoreactivity for PKCγ and p47phox; however, lysoPCs induced a FRET positivity interaction between PKCγ and p47phox at 5 min. (D) Isolated PMNs from WT and PKCγ KO mice were primed with albumin or lysoPCs, incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies to p47phox (red) or PKCδ (green), and analyzed by digital microscopy. PMNs from the WT and KO mice demonstrated immunoreactivity for PKCδ and p47phox in albumin-treated or lysoPC-primed PMNs. However, only the WT mice exhibited a positive FRET (red) between PKCδ and p47phox (middle right), whereas the PMNs from PKCγ KO mice did not. The data in this figure are representative of 3 identical experiments.

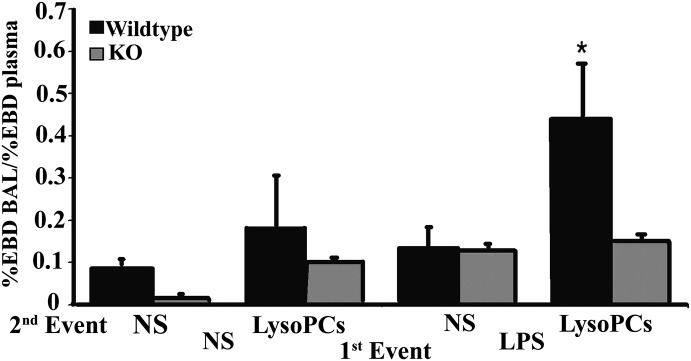

Lung injury in PKCγ KO mice

As lysoPCs induce ALI as the second event in a 2-event in vivo model, an identical murine model was used consisting of WT and PKCγ KO mice [19]. The rodents were injected intraperitoneally with NS or LPS (2 mg/kg), and the animals were incubated for 2 h and then infused via the tail vein with NS or lysoPCs (4.5 μM), followed by EBD [19]. WT mice that received LPS IP, followed by lysoPC infusion, developed significant EBD lung leak versus mice that were transfused with NS or received NS as the first event, regardless of the second (Fig. 10). However, PKCγ KO mice that received LPS, followed by the infusion of lysoPCs, did not evidence ALI (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. LysoPCs cause ALI in WT but not PKCγ KO mice.

WT and PKCγ KO mice were treated with NS or LPS by intraperitoneal injection, 2 h before being transfused by tail vein with NS or lysoPCs, followed by EBD injection. ALI was measured as the percent of EBD leak into the lungs. WT mice (black bars) given LPS, followed by lysoPC infusion, had a significant increase in lung leak compared with the WT mice treated with NS and transfused with lysoPCs or NS and WT mice treated with LPS and infused with NS (P < 0.05). The PKCγ KO mice (gray bars) did not have any significant lung leak in any group, including NS/NS, NS/lysoPC, and LPS/NS. Importantly, when the PKCγ KO mice were treated with LPS and then infused with lysoPCs, there was no increased lung leak/ALI (*P < 0.05, each bar consists of 4 mice).

DISCUSSION

LysoPCs at concentrations found in stored, cellular blood components cause activation of the Src family kinase Hck, which coprecipitates with PKCδ and PKCγ and the cytoskeletal protein WAVE2. From time courses, intracellular neutralization of specific proteins, and the use of in vitro assays and multiple inhibitors, Hck activates PKCδ via Tyr phosphorylation (Tyr311 and Tyr525), which in turn, activates PKCγ via Ser and Thr phosphorylation (Thr514). The PKCδ/PKCγ complex also coprecipitates with lipid rafts in the membrane, presumably as a result of recruitment to this compartment through lysoPC priming [38]. LysoPCs also elicited coprecipitation of PKCγ and activated PKCγ with p47phox, as well as a FRET+ physical association (5 nm distance) of PKCγ with p47phox. Such data indicate that PKCγ phosphorylates p47phox as a result of these coprecipitations and the physical interactions between enzymes and substrates [12, 26]. Some of these data were confirmed using PKCγ KO and WT mice, in which lysoPCs caused priming of WT PMNs but not PKCγ KO PMNs, and in the PKCγ KO murine PMNs, lysoPCs do not induce phosphorylation and translocation of p47phox. Furthermore, lysoPCs caused coprecipitation of Hck with PKCδ and PKCγ, but the PKCδ:PKCγ complex was not observed in the PKCγ KO PMNs. To determine if PKCγ was responsible for lysoPC-mediated changes in PMN physiology in vivo, both WT and PKCγ KO mice were used with a previously published rodent model for PMN-mediated ALI [19, 25]. In LPS-treated mice, lysoPCs elicited ALI in the WT mice but did not cause ALI in PKCγ KO mice, thereby indicating its relevance in the observed PMN priming and PMN-induced ALI in the setting of TRALI [19]. Importantly, PKCγ KO mice contain normal levels of the other PKC isoenzymes, including PKCα, -βI, -βII, and -δ, such that the observed lack of ALI could not be attributed to their absence [39, 40].

Previous data have demonstrated that lysoPCs cause activation of PKC in mast cells, platelets, and endothelial cells, and the reported data are not surprising [41–44]. Activation of PKCδ is accomplished through Tyr phosphorylation, which has been linked to Src kinases and phosphorylation of Tyr311 with a second Tyr phosphorylation, which is variable [45–50]. PKCδ has been associated with assembly of the PMN oxidase, especially with the phosphorylation of p47phox, and it contains an actin-binding domain, which may be associated with changes in actin polymerization, necessary for shape change and chemotaxis [51–54]. Thus, activation of PKCδ by Hck is plausible, as demonstrated by its physical association with PKCδ in intact PMNs, pPKCδ at Tyr311 and Tyr525 (the human equivalent of Tyr523 phosphorylation of rodent PKCδ), the ability of active recombinant Hck to cause Tyr pPKCδ, and the inhibition by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Both PP2, a selective Src kinase inhibitor, and genistein, a Tyr-kinase antagonist, inhibited lysoPC priming, with the former decreasing pPKCδ [35, 55]. Human pPKCδ at Ser662, similar to Ser664 in the rodent PKCδ, is likely a result of autophosphorylation [45, 56].

Conversely, PKCγ was reported to be limited to the CNS and then was found in the lens of the eye, in epithelial cells, in HL-60 cells, a leukemia of granulocytic origin, and in rat PMNs [57–61]. In neurons, PKCγ responds to rapid changes in cytosolic Ca2+, causes remodeling of the synaptic potential, has a role in long-term potentiation, and in some cases, is inhibitory [40, 62–68]. However, PKCγ is not required for phorbol ester stimulation of neurons and has no role in the PMA-mediated changes in the long-term potentiation of the synaptic response, even though it is the dominant PKC isoform in neurons and is not depleted following long-term phorbol ester treatment of 3T3-F422A, unlike other cPKCs [67, 69]. Moreover, PKCγ also responds to a rapid cytosolic Ca2+ flux in neurons [66]. These data parallel lysoPC priming of PMNs, which causes rapid changes in cytosolic Ca2+, Hck activation, and stimulation of PKCδ and PKCγ [13]. Conversely, PMA activation of the respiratory burst does not require changes in cytosolic Ca2+ and may occur when all cytosolic Ca2+ is buffered by BAPTA-AM, as shown. Thus, the inability of PMA to cause translocation of PKCγ is not unexpected from the data in neurons [40, 62–68].

Insulin-like growth factor 1 causes activation of PKCδ and PKCγ in colonic epithelial cells, which are not interrelated, and lysoPCs to mediate their biologic effects through activation of PKC, although these data relied on PKC antagonists [42–44, 58]. In contrast, Ca2+ chelation inhibited PKCγ activation and membrane translocation but not PKCδ. However, inhibition of PKCδ activity by 2 different inhibitors, which do not affect PKCγ at the concentrations used, decreased the translocation of PKCδ and PKCγ, indicating that PKCδ activity is required for their interaction membrane translocation. In addition, although there is significant cross-talk and plasticity of PKC signaling between the cPKC and nPKC isoforms and complexes of these 2 distinct PKC isozymes, which translocate together in many cell lines, the direct activation of PKCγ by PKCδ has not been demonstrated [54, 70–74]. There is background PKC activity in the cytosol for many of the isoenzymes investigated, which may be a result of other distinct cellular processes. The focus of this manuscript was on the PKC isoenzymes that translocated to the membrane/lipid rafts and their activation through coprecipitation and FRET+ physical interactions with specific substrates.

The coprecipitation of PKCδ and PKCγ with WAVE2 is not unexpected. WAVE2 and similar Wiskott-Aldrich proteins are scaffold proteins that regulate actin assembly in and promote polarized chemotaxis in PMNs [75–79]. LysoPCs are effective chemoattractants and rapidly cause changes in the PMN cytoskeleton and activate Hck, a Src family tyrosine kinase important for chemoattractant signaling and phosphorylation of SCAR (suppressor of cAMP receptor)/WAVE2 proteins [13, 16, 80, 81]. Moreover, the coprecipitation of PKCγ and PKCδ with lipid rafts elicited by lysoPCs is similar to that reported for FcγR activation of PMNs [38].

In previous studies, lysoPC-mediated Hck activation was the direct result of the Gβγ subunit, and Hck-mediated activation of PKCδ is novel [16]. The presence of PKCγ in human PMNs, its activation by PKCδ, and its requirement for lysoPC priming through phosphorylation and translocation of p47phox are also novel. The identification of precise signaling pathways and specific proteins may lead to novel pharmacological inhibition of the described signaling, which could inhibit TRALI, in which lysoPCs have been implicated both in in vivo models and in humans [19, 22, 23, 82, 83].

AUTHORSHIP

M.R.K. contributed to study design, performed most of the experiments, and primarily wrote the article. N.J.D.M. contributed to the microscopy design and experiments. A.B. contributed to study design. D.J.E. contributed to the study design and performed the experiments. F.G. contributed to the microscopy experiments and design. S.Y.K. contributed the microscopy experiments and the animal work. X.M. contributed to the study design and animal work. S.M. contributed to the RNA experiments and design. C.C.S. contributed to study design and writing of the article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The studies were supported by Bonfils Blood Center and Grant HL59355 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Grant GM049222 from the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Glossary

- ALI

acute lung injury

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- Bis I

bisindolylmaleimide I

- CCD

charge-coupled device

- cPKC

classical protein kinase C

- CTB

cholera toxin B

- EBD

Evans Blue dye

- fMLF

N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- KO

knockout

- lysoPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- nPKC

novel protein kinase C

- NS

normal saline

- p47phox

47 kDa phagocyte oxidase protein

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- pHck

phosphorylated Hck

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte/neutrophil

- PP2

pyrazolpyrimidine

- pPKC

phosphorylated protein kinase C

- SAEC

small airway epithelial cell

- TRALI

transfusion-related acute lung injury

- USP

U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention

- WAVE2

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family verprolin-homologous protein 2

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

- WT

wild-type mouse

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malech H. L., Gallin J. I. (1987) Current concepts: immunology. Neutrophils in human diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 317, 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlos T. M., Harlan J. M. (1994) Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood 84, 2068–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doerschuk C. M. (2001) Mechanisms of leukocyte sequestration in inflamed lungs. Microcirculation 8, 71–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granger D. N., Kubes P. (1994) The microcirculation and inflammation: modulation of leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. J. Leukoc. Biol. 55, 662–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith C. W. (2008) 3. Adhesion molecules and receptors. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121 (2 Suppl) S375–S379, quiz S414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung Y. L., Silliman C. C. (2009) The role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfus. Med. Rev. 23, 266–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheppard F. R., Kelher M. R., Moore E. E., McLaughlin N. J., Banerjee A., Silliman C. C. (2005) Structural organization of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase: phosphorylation and translocation during priming and activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78, 1025–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vercellotti G.M., Moldow C.F., Wickham N.W., Jacob H.S. (1990) Endothelial cell platelet-activating factor primes neutrophil responses: amplification of endothelial activation by neutrophil products. J. Lipid Mediat. (2 Suppl), S23–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S., Feinstein S. I., Dodia C., Sorokina E., Lien Y. C., Nguyen S., Debolt K., Speicher D., Fisher A. B. (2011) Peroxiredoxin 6 phosphorylation and subsequent phospholipase A2 activity are required for agonist-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelium and alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11696–11706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLeo F. R., Renee J., McCormick S., Nakamura M., Apicella M., Weiss J. P., Nauseef W. M. (1998) Neutrophils exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide upregulate NADPH oxidase assembly. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leavey P. J., Gonzalez-Aller C., Thurman G., Kleinberg M., Rinckel L., Ambruso D. W., Freeman S., Kuypers F. A., Ambruso D. R. (2002) A 29-kDa protein associated with p67phox expresses both peroxiredoxin and phospholipase A2 activity and enhances superoxide anion production by a cell-free system of NADPH oxidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45181–45187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin N. J., Banerjee A., Khan S. Y., Lieber J. L., Kelher M. R., Gamboni-Robertson F., Sheppard F. R., Moore E. E., Mierau G. W., Elzi D. J., Silliman C. C. (2008) Platelet-activating factor-mediated endosome formation causes membrane translocation of p67phox and p40phox that requires recruitment and activation of p38 MAPK, Rab5a, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 180, 8192–8203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silliman C. C., Elzi D. J., Ambruso D. R., Musters R. J., Hamiel C., Harbeck R. J., Paterson A. J., Bjornsen A. J., Wyman T. H., Kelher M., England K. M., McLaughlin-Malaxecheberria N., Barnett C. C., Aiboshi J., Bannerjee A. (2003) Lysophosphatidylcholines prime the NADPH oxidase and stimulate multiple neutrophil functions through changes in cytosolic calcium. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aiboshi J., Moore E. E., Ciesla D. J., Silliman C. C. (2001) Blood transfusion and the two-insult model of post-injury multiple organ failure. Shock 15, 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyman T. H., Bjornsen A. J., Elzi D. J., Smith C. W., England K. M., Kelher M., Silliman C. C. (2002) A two-insult in vitro model of PMN-mediated pulmonary endothelial damage: requirements for adherence and chemokine release. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283, C1592–C1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan S. Y., McLaughlin N. J., Kelher M. R., Eckels P., Gamboni-Robertson F., Banerjee A., Silliman C. C. (2010) Lysophosphatidylcholines activate G2A inducing G(αi)₋₁-/G(αq/)₁₁- Ca²(+) flux, G(βγ)-Hck activation and clathrin/β-arrestin-1/GRK6 recruitment in PMNs. Biochem. J. 432, 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akita H., Creer M. H., Yamada K. A., Sobel B. E., Corr P. B. (1986) Electrophysiologic effects of intracellular lysophosphoglycerides and their accumulation in cardiac lymph with myocardial ischemia in dogs. J. Clin. Invest. 78, 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azzazy H. M., Pelsers M. M., Christenson R. H. (2006) Unbound free fatty acids and heart-type fatty acid-binding protein: diagnostic assays and clinical applications. Clin. Chem. 52, 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelher M. R., Masuno T., Moore E. E., Damle S., Meng X., Song Y., Liang X., Niedzinski J., Geier S. S., Khan S. Y., Gamboni-Robertson F., Silliman C. C. (2009) Plasma from stored packed red blood cells and MHC class I antibodies causes acute lung injury in a 2-event in vivo rat model. Blood 113, 2079–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silliman C. C., Clay K. L., Thurman G. W., Johnson C. A., Ambruso D. R. (1994) Partial characterization of lipids that develop during the routine storage of blood and prime the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 124, 684–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silliman C. C., Dickey W. O., Paterson A. J., Thurman G. W., Clay K. L., Johnson C. A., Ambruso D. R. (1996) Analysis of the priming activity of lipids generated during routine storage of platelet concentrates. Transfusion 36, 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silliman C. C., Voelkel N. F., Allard J. D., Elzi D. J., Tuder R. M., Johnson J. L., Ambruso D. R. (1998) Plasma and lipids from stored packed red blood cells cause acute lung injury in an animal model. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1458–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silliman C. C., Boshkov L. K., Mehdizadehkashi Z., Elzi D. J., Dickey W. O., Podlosky L., Clarke G., Ambruso D. R. (2003) Transfusion-related acute lung injury: epidemiology and a prospective analysis of etiologic factors. Blood 101, 454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan J. J., Jung J. S., Lee J. E., Lee J., Huh S. O., Kim H. S., Jung K. C., Cho J. Y., Nam J. S., Suh H. W., Kim Y. H., Song D. K. (2004) Therapeutic effects of lysophosphatidylcholine in experimental sepsis. Nat. Med. 10, 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silliman C. C., Moore E. E., Kelher M. R., Khan S. Y., Gellar L., Elzi D. J. (2011) Identification of lipids that accumulate during the routine storage of prestorage leukoreduced red blood cells and cause acute lung injury. Transfusion 51, 2549–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaughlin N. J., Banerjee A., Kelher M. R., Gamboni-Robertson F., Hamiel C., Sheppard F. R., Moore E. E., Silliman C. C. (2006) Platelet-activating factor-induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis requires beta-arrestin-1 recruitment and activation of the p38 MAPK signalosome at the plasma membrane for actin bundle formation. J. Immunol. 176, 7039–7050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckels P. C., Banerjee A., Moore E. E., McLaughlin N. J., Gries L. M., Kelher M. R., England K. M., Gamboni-Robertson F., Khan S. Y., Silliman C. C. (2009) Amantadine inhibits platelet-activating factor induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis in human neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C886–C897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chazotte B. (2011) Fluorescent labeling of membrane lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011, pdb.prot5625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson J. L., Moore E. E., Hiester A. A., Tamura D. Y., Zallen G., Silliman C. C. (1999) Disparities in the respiratory burst between human and rat neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keranen L. M., Dutil E. M., Newton A. C. (1995) Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr. Biol. 5, 1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin D., Harris R., Stutzman R., Zampighi G. A., Davidson H., Takemoto D. J. (2007) Protein kinase C-gamma activation in the early streptozotocin diabetic rat lens. Curr. Eye Res. 32, 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gschwendt M., Müller H. J., Kielbassa K., Zang R., Kittstein W., Rincke G., Marks F. (1994) Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu D. M., Fang W. H., Narla R. K., Uckun F. M. (1999) A requirement for protein kinase C inhibition for calcium-triggered apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evenou J. P., Wagner J., Zenke G., Brinkmann V., Wagner K., Kovarik J., Welzenbach K. A., Weitz-Schmidt G., Guntermann C., Towbin H., Cottens S., Kaminski S., Letschka T., Lutz-Nicoladoni C., Gruber T., Hermann-Kleiter N., Thuille N., Baier G. (2009) The potent protein kinase C-selective inhibitor AEB071 (sotrastaurin) represents a new class of immunosuppressive agents affecting early T-cell activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330, 792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang J. L., Lee H. W., Lee H. S., Pack I. S., Chong Y., Castranova V., Koh Y. (2001) Genistein prevents nuclear factor-kappa B activation and acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 164, 2206–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown D. A., London E. (1998) Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovárová M., Tolar P., Arudchandran R., Dráberová L., Rivera J., Dráber P. (2001) Structure-function analysis of Lyn kinase association with lipid rafts and initiation of early signaling events after Fcepsilon receptor I aggregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8318–8328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao D., Segal A. W., Dekker L. V. (2003) Lipid rafts determine efficiency of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 550, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abeliovich A., Chen C., Goda Y., Silva A. J., Stevens C. F., Tonegawa S. (1993) Modified hippocampal long-term potentiation in PKC gamma-mutant mice. Cell 75, 1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narita M., Mizoguchi H., Suzuki T., Narita M., Dun N. J., Imai S., Yajima Y., Nagase H., Suzuki T., Tseng L. F. (2001) Enhanced mu-opioid responses in the spinal cord of mice lacking protein kinase Cgamma isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15409–15414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirai Y., Saito N. (2002) Activation mechanisms of protein kinase C: maturation, catalytic activation, and targeting. J. Biochem. 132, 663–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kugiyama K., Ohgushi M., Sugiyama S., Murohara T., Fukunaga K., Miyamoto E., Yasue H. (1992) Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits surface receptor-mediated intracellular signals in endothelial cells by a pathway involving protein kinase C activation. Circ. Res. 71, 1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marquardt D. L., Walker L. L. (1991) Lysophosphatidylcholine induces mast cell secretion and protein kinase C activation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 88, 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murohara T., Scalia R., Lefer A. M. (1996) Lysophosphatidylcholine promotes P-selectin expression in platelets and endothelial cells. Possible involvement of protein kinase C activation and its inhibition by nitric oxide donors. Circ. Res. 78, 780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benes C., Soltoff S. P. (2001) Modulation of PKCdelta tyrosine phosphorylation and activity in salivary and PC-12 cells by Src kinases. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C1498–C1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gschwendt M., Kielbassa K., Kittstein W., Marks F. (1994) Tyrosine phosphorylation and stimulation of protein kinase C delta from porcine spleen by src in vitro. Dependence on the activated state of protein kinase C delta. FEBS Lett. 347, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Junttila I., Bourette R. P., Rohrschneider L. R., Silvennoinen O. (2003) M-CSF induced differentiation of myeloid precursor cells involves activation of PKC-delta and expression of Pkare. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W., Mischak H., Yu J. C., Wang L. M., Mushinski J. F., Heidaran M. A., Pierce J. H. (1994) Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C-delta in response to its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2349–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumandea M. P., Rybin V. O., Hinken A. C., Wang C., Kobayashi T., Harleton E., Sievert G., Balke C. W., Feinmark S. J., Solaro R. J., Steinberg S. F. (2008) Tyrosine phosphorylation modifies protein kinase C delta-dependent phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22680–22689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu L., Brodie C., Balasubramanian S., Eckert R. L. (2008) Multiple PKCdelta tyrosine residues are required for PKCdelta-dependent activation of involucrin expression--a key role of PKCdelta-Y311. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 833–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bey E. A., Xu B., Bhattacharjee A., Oldfield C. M., Zhao X., Li Q., Subbulakshmi V., Feldman G. M., Wientjes F. B., Cathcart M. K. (2004) Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J. Immunol. 173, 5730–5738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fontayne A., Dang P. M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., El-Benna J. (2002) Phosphorylation of p47phox sites by PKC alpha, beta II, delta, and zeta: effect on binding to p22phox and on NADPH oxidase activation. Biochemistry 41, 7743–7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.López-Lluch G., Bird M. M., Canas B., Godovac-Zimmerman J., Ridley A., Segal A. W., Dekker L. V. (2001) Protein kinase C-delta C2-like domain is a binding site for actin and enables actin redistribution in neutrophils. Biochem. J. 357, 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamori T., Inanami O., Nagahata H., Kuwabara M. (2004) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates the phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase component p47(phox) by controlling cPKC/PKCdelta but not Akt. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fumagalli L., Zhang H., Baruzzi A., Lowell C. A., Berton G. (2007) The Src family kinases Hck and Fgr regulate neutrophil responses to N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. J. Immunol. 178, 3874–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gschwendt M., Kittstein W., Kielbassa K., Marks F. (1995) Protein kinase C delta accepts GTP for autophosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 206, 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abeliovich A., Paylor R., Chen C., Kim J. J., Wehner J. M., Tonegawa S. (1993) PKC gamma mutant mice exhibit mild deficits in spatial and contextual learning. Cell 75, 1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.André F., Rigot V., Remacle-Bonnet M., Luis J., Pommier G., Marvaldi J. (1999) Protein kinases C-gamma and -delta are involved in insulin-like growth factor I-induced migration of colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 116, 64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin D., Zhou J., Zelenka P. S., Takemoto D. J. (2003) Protein kinase Cgamma regulation of gap junction activity through caveolin-1-containing lipid rafts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 5259–5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aquino A., Warren B. S., Omichinski J., Hartman K. D., Glazer R. I. (1990) Protein kinase C-gamma is present in adriamycin resistant HL-60 leukemia cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 166, 723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsao L. T., Wang J. P. (1997) Translocation of protein kinase C isoforms in rat neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Angenstein F., Riedel G., Reymann K. G., Staak S. (1994) Hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo induces translocation of protein kinase C gamma. Neuroreport 5, 381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashida N., Ueyama T., Rikitake K., Shirai Y., Eto M., Kondoh T., Kohmura E., Saito N. (2008) Ca2+ oscillation induced by P2Y2 receptor activation and its regulation by a neuron-specific subtype of PKC (gammaPKC). Neurosci. Lett. 446, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baumgartner R. A., Ozawa K., Cunha-Melo J. R., Yamada K., Gusovsky F., Beaven M. A. (1994) Studies with transfected and permeabilized RBL-2H3 cells reveal unique inhibitory properties of protein kinase C gamma. Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Codazzi F., Teruel M. N., Meyer T. (2001) Control of astrocyte Ca(2+) oscillations and waves by oscillating translocation and activation of protein kinase C. Curr. Biol. 11, 1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Codazzi F., Di Cesare A., Chiulli N., Albanese A., Meyer T., Zacchetti D., Grohovaz F. (2006) Synergistic control of protein kinase Cgamma activity by ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor inputs in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 26, 3404–3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goda Y., Stevens C. F., Tonegawa S. (1996) Phorbol ester effects at hippocampal synapses act independently of the gamma isoform of PKC. Learn. Mem. 3, 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Narita M., Mizoguchi H., Khotib J., Suzuki M., Ozaki S., Yajima Y., Narita M., Tseng L. F., Suzuki T. (2002) Influence of a deletion of protein kinase C gamma isoform in the G-protein activation mediated through opioid receptor-like-1 and mu-opioid receptors in the mouse pons/medulla. Neurosci. Lett. 331, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacKenzie S., Fleming I., Houslay M. D., Anderson N. G., Kilgour E. (1997) Growth hormone and phorbol esters require specific protein kinase C isoforms to activate mitogen-activated protein kinases in 3T3-F442A cells. Biochem. J. 324, 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ariga T., Jarvis W. D., Yu R. K. (1998) Role of sphingolipid-mediated cell death in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Lipid Res. 39, 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kampfer S., Hellbert K., Villunger A., Doppler W., Baier G., Grunicke H. H., Uberall F. (1998) Transcriptional activation of c-fos by oncogenic Ha-Ras in mouse mammary epithelial cells requires the combined activities of PKC-lambda, epsilon and zeta. EMBO J. 17, 4046–4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naor Z., Harris D., Shacham S. (1998) Mechanism of GnRH receptor signaling: combinatorial cross-talk of Ca2+ and protein kinase C. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 19, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Puente L. G., He J. S., Ostergaard H. L. (2006) A novel PKC regulates ERK activation and degranulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes: Plasticity in PKC regulation of ERK. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rex E. B., Rankin M. L., Yang Y., Lu Q., Gerfen C. R., Jose P. A., Sibley D. R. (2010) Identification of RanBP 9/10 as interacting partners for protein kinase C (PKC) gamma/delta and the D1 dopamine receptor: regulation of PKC-mediated receptor phosphorylation. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ibarra N., Pollitt A., Insall R. H. (2005) Regulation of actin assembly by SCAR/WAVE proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 1243–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patel F. B., Bernadskaya Y. Y., Chen E., Jobanputra A., Pooladi Z., Freeman K. L., Gally C., Mohler W. A., Soto M. C. (2008) The WAVE/SCAR complex promotes polarized cell movements and actin enrichment in epithelia during C. elegans embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 324, 297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ura S., Pollitt A. Y., Veltman D. M., Morrice N. A., Machesky L. M., Insall R. H. (2012) Pseudopod growth and evolution during cell movement is controlled through SCAR/WAVE dephosphorylation. Curr. Biol. 22, 553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weiner O. D., Servant G., Welch M. D., Mitchison T. J., Sedat J. W., Bourne H. R. (1999) Spatial control of actin polymerization during neutrophil chemotaxis. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weiner O. D., Marganski W. A., Wu L. F., Altschuler S. J., Kirschner M. W. (2007) An actin-based wave generator organizes cell motility. PLoS Biol. 5, e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Giagulli C., Ottoboni L., Caveggion E., Rossi B., Lowell C., Constantin G., Laudanna C., Berton G. (2006) The Src family kinases Hck and Fgr are dispensable for inside-out, chemoattractant-induced signaling regulating beta 2 integrin affinity and valency in neutrophils, but are required for beta 2 integrin-mediated outside-in signaling involved in sustained adhesion. J. Immunol. 177, 604–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vincent C., Maridonneau-Parini I., Le Clainche C., Gounon P., Labrousse A. (2007) Activation of p61Hck triggers WASp- and Arp2/3-dependent actin-comet tail biogenesis and accelerates lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19565–19574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Silliman C. C., Bjornsen A. J., Wyman T. H., Kelher M., Allard J., Bieber S., Voelkel N. F. (2003) Plasma and lipids from stored platelets cause acute lung injury in an animal model. Transfusion 43, 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Silliman C. C., Khan S. Y., Ball J. B., Kelher M. R., Marschner S. (2010) Mirasol Pathogen Reduction Technology treatment does not affect acute lung injury in a two-event in vivo model caused by stored blood components. Vox Sang. 98, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.