Gender identity disorder is being given greater attention and importance by the medical profession. Although its aetiology is unclear, some evidence suggests that it has a neurobiological basis. The condition is no longer confused with sexual orientation preference and other gender related disorders. Social stigma remains, and patients need multidisciplinary assessment and care.

Terminology

The designation of sex has always been established by looking at the anatomical sex, and the term gender identity describes whether a person senses himself or herself to be masculine or feminine. Gender role describes how people publicly express themselves in their clothing, use of cosmetics, hairstyle, conversation, body language, appearance, and behaviour. Usually, gender identity and gender role are congruous, but in people with gender identity disorder, severe incongruity exists between anatomical sex and gender identity, and the person has persistent discomfort with his or her anatomical sex, usually from childhood. A sense of inappropriateness is felt in the gender role of that sex, and such people have a strong, ongoing, crossgender identification, with a desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex. Usually they have a desire for hormonal therapy and surgery to make their body as congruent as possible with the desired gender identity.

It is essential to recognise that sexual orientation—the sex someone finds erotically attractive—is distinct from gender identity and role, and it may be heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual. The proportion of heterosexual, bisexual, and gay people is no different in transgendered people than in non-transgendered people, and most studies suggest that heterosexuality occurs after surgical reassignment.

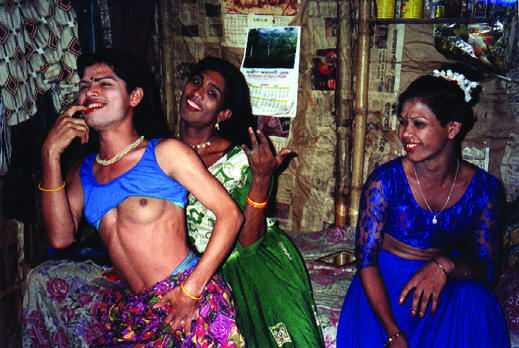

Figure 1.

These people are not transvestites or transsexuals. They are Sylhet kothis, from South Asia. Although men, they see themselves as feminine and adopt mannerisms to attract panthis—real men. Sociocultural, religious, and family pressures ensure that most kothis eventually marry and produce children, no matter how long they attempt to delay this process. This intense pressure, not surprisingly, produces a range of major psychological effects. With permission of Naz Foundation International

Aetiology

The aetiology of gender dysphoria is controversial. Some believe it reflects the physical and mental health of the mother during pregnancy, while others believe that a disturbed interaction occurs between parts of the brain and sex hormones during development of the fetus because by the sixth week of gestation, brain sex is a reality, and gender programming may have started. Other theorists have described the condition to reflect developmental problems during early life. There is an emphasis on the nurturing aspects of gender reinforcements and programming. Children may have to suppress their natural behaviours and tendencies to conform and fit in, which can cause undue distress.

Some evidence supports the idea that transsexualism is a neurodevelopmental condition during fetal growth. Several sexually dimorphic nuclei have been found in the hypothalamic area of the brain, particularly the sexually dimorphic limbic nucleus (the central subdivision of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis) that becomes fully matured in the human brain by early adulthood.

Table 1.

Intersex

| A delay in gender assignment with cosmetic surgery for intersex patients until the patient can give informed, adult consent is now generally accepted. In cases of doubt, such as intersexuality or hermaphrodism (in clinical cases, like adrenal hyperplasia or androgen resistance), however, determination of genetic sex is essential |

Zhou et al found that the biological structure in the brains of male to female transsexual people had a totally female pattern that was not attributable to sex hormone therapy. Kruijver et al later found that regardless of sexual orientation, men had almost twice as many somatostatin neurones as women. These inhibit thyroid stimulating hormone and growth hormones in the hypothalamus. The number of neurones in male to female transsexual people was similar to that in women, whereas the number of neurones in female to male transsexual people was similar to that in men. This seems to support a neurobiological basis for gender identity disorder.

This article is adapted from the second edition of the ABC of Sexual Health, which will be published later this year. A list of support networks for patients is on bmj.com

People who identify themselves with transsexualism are known as transpeople. Those who are assigned as female at birth but who sense their body sexual function as, and identify themselves as, male are known as transmen, and vice versa. Once treatment through hormonal and surgical intervention is complete, many people no longer identify themselves as trans but simply as men or women

When a predisposition for transsexualism exists, various factors, including psychosexual matters, may subsequently have a role in outcome

Hormones may influence considerably the dimorphic development at several critical times: initially during the fetal period, around the time of birth, and, most likely, after birth.

Table 2.

Possible contributors to an altered hormone environment

| • Genetic influences |

| • Medication |

| • Environmental influences |

| • Stress of or trauma to the mother during pregnancy |

Differential diagnosis

Tranvestism

In cross dressing transvestism, men find intense relief in dressing in women's clothing. In these circumstances, progression to sexual arousal and activity or an intense desire to seek sexual reassignment surgery is rare. In transvestite fetishism, the person, who is almost invariably a man, obtains sexual arousal as a consequence of dressing in women's clothing. Masturbation or other sexual activity associated with the cross dressing is not unusual, with the man later discarding the clothing, often with a degree of repulsion.

Table 3.

Case example of transvestite fetishism (from Krafft-Ebing, 1887)

| J, a young butcher, when arrested, was found to be wearing underneath his overcoat a bodice, a corset, a vest, a jacket, a collar, a jersey and a chemise, also fine stockings and garters. Since he was eleven, he was troubled by the desire to wear a chemise of his elder sister. Whenever he could do it unnoticed, he indulged in this pleasure, and since the age of puberty, the wearing of such a garment would bring on ejaculation. When he became independent, he bought chemises and other articles of female toilet. To put on such garments was the great aim of his sexual instinct and he begged the hospital physician to let him wear female attire. |

Legal issues

In the United Kingdom in 1970, a legal judgment removed the right to correct birth certificates. This meant that transpeople lost their rights to marry, foster, adopt, and receive support for domestic violence. Custodial sentencing placements also were affected.

A legal judgment from the European Court of Justice in 1998 meant that discrimination on the grounds of a person's transsexualism became illegal, and rights were put in effect by the Sex Discrimination (Gender Reassignment) Regulations that year.

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 makes provision for a person of either gender, aged at least 18, to make an application for a gender recognition certificate on the basis of living in the gender other than identified on the original birth certificate. A diagnosis of gender dysphoria and evidence of having lived in the acquired gender for at least two years will be necessary. It will not be necessary for full gender reassignment surgery to have taken place. A short certificate of birth can then be issued.

Figure 2.

Standards of care

The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association laid out internationally agreed standards of care for transgendered patients who want to change to their chosen gender. These standards outline the pathways of treatment that should be available to patients seeking help. They include the role of mental health professionals in diagnosing accurately any comorbid psychiatric conditions, confirming the gender disorder, and ensuring that patients are offered appropriate treatment. Up to 1 in 10 transpeople have problems with mental illness, genital mutilation, or suicide attempts.

Figure 3.

Transmale (left) to female (right)

Transpeople should be counselled about the range of treatment options and implications and, if necessary, should be encouraged to have psychotherapy. The professional should ascertain eligibility and readiness for progression to hormone and surgical therapy. Whenever possible, this should be done within the context of a multidisciplinary team and should take into account the needs of the individual patient rather than enforcing a rigid package of care.

Table 4.

Three requirements for hormone therapy

| • Patients have had the opportunity of further consolidation of their chosen gender identity with psychotherapy or real life experience in the preferred gender role |

| • They have made progress in mastering other identified problems that lead to improvements in or continuing stable mental health |

| • They are likely to take hormones in a responsible manner |

The real life experience can happen at a predetermined time or before starting hormonal therapy; the decision usually depends on local policy. The person must aim to maintain full time or part time employment or function as a student or in a community based volunteer activity.

Table 5.

Drugs often used in gender clinics

| Masculinisation |

|---|

| • Testosterone 250 mg intramuscularly every three weeks or transdermal patches or gels |

| Feminisation |

|---|

| Aged < 40 years |

| • Estradiol 0.5-2 mg once to three times a day to establish satisfactory serum levels |

| Aged ≥ 40 years |

| • Estradiol transdermal system 25-100 μg patch (Estraderm TTX) applied to the skin and changed twice weekly |

| In addition, for all age groups, an antiandrogen, such as cyproterone acetate 50 mg 1-2 tablets daily or spironolactone 100 mg once daily, may be necessary |

| Patients must be fully counselled about the off licence status of these drugs |

He or she must provide written documentation to prove that people other than the therapists acknowledge that the patient successfully passes and functions in the chosen gender role. People who are retired may have some problems in providing such documentation.

Clear guidelines about haematological, biochemical, and endocrinological monitoring should be given before and during treatment with hormones. When starting hormonal therapy, the desired effects and the positive and negative side effects must be outlined to the patient and appropriate consent should be obtained. It is good practice to ensure that any partner of the patient is aware of the effects of prescribed medications. Reproductive options with gamete storage should be taken into account and explicit consent obtained. Speech and language therapy and hair removal techniques should be offered at this stage.

Gender reassignment surgery

After a minimum of 12 months' supervision within the real life experience, the opportunity for surgery can be considered. As with entering hormonal therapy, criteria of eligibility and readiness need to be met. When the supervising team is convinced that these have been satisfied, a second psychiatric or medical opinion should be sought, preferably from an experienced clinician from another service. If this opinion is supportive, the patients should be referred to a specialist surgeon. Surgical options include breast surgery and genital reassignment surgery. The patient must be fully counselled about the limitations of surgery and the potential complications.

Figure 4.

Male to female surgery. With permission of David Ralph

Transmen may be offered bilateral mastectomy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and fashioning of a penis and scrotum. Possible operations for transwomen are removal of the penis and testes and fashioning a new vagina and clitoris, as well as techniques such as breast augmentation, reshaping of the nose and the cricothyroid cartilages, facial remodelling, and hair transplants. Adequate postoperative care from the surgical, hormonal, and therapeutic points of view must be provided.

Figure 5.

Female to male surgery—new penis: flaccid. With permission of David Ralph

Studies that have reported the outcome of sex reassignment surgery have found varied results. One report suggests satisfaction with the surgical results in 87% of male to female patients and 97% of female to male patients. Young age, good family and social support, and success of the surgical procedures all correlate with patients' long term satisfaction.

Supplementary Material

Kevan Wylie is consultant in sexual medicine, Porterbrook Clinic, Sheffield

The ABC of Sexual Health is edited by John Tomlinson, specialist in sexual health, Winchester, john@jptomlinson.com

Further reading and resources

- • Zhou J-N, Hofman MA, Gooren LJG, Swaab DF. A sex difference in the human brain and its relation to transsexuality. Nature 1995;378: 68-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Kruijver FPM, Zhou J-N, Pool CW, Hofman MA, Gooren LJG, Swaab DF. Male to female transsexuals have female neuron numbers in a limbic nucleus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85: 2034-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. The standards of care for gender identity disorders (sixth version). www.symposion.com/ijt/soc_2001/index.htm

- • Futterweit W. Endocrine therapy of transsexuals and potential complications of long term treatment. Arch Sex Behaviour 1998;27: 209-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Blanchard R, Steiner BW. Clinical management of gender identity disorders in children and adults. Washington: American Psychiatric Press, 1990. www.symposium.com/ijt/soc_2001/index.htm

- • Blanchard R, Federoff JP. The case for and against publicly funded transsexual surgery. Psych Rounds 2000;4: 2 [Google Scholar]

- • Nanda S. Neither man nor woman—Hijiras of India. New York: Wadsworth Publishing, 1990

- • Jaffrey Z. The invisibles—a tale of the eunuchs of India. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1997

- • Department for Constitutional Affairs. Government policy concerning transsexual people. London: DCA, 2004. http://www.dca.gov.uk/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.