Abstract

The purpose of the study was to test a novel treatment that carbodiimide-derivatized-hyaluronic acid-lubricin (cd-HA-lubricin) combined cell-based therapy in an immobilized flexor tendon repair in a canine model. Seventy-eight flexor tendons from 39 dogs were transected. One tendon was treated with cd-HA-lubricin plus an interpositional graft of 8 × 105 BMSCs and GDF-5. The other tendon was repaired without treatment. After 21 day of immobilization, 19 dogs were sacrificed; the remaining 20 dogs underwent a 21-day rehabilitation protocol before euthanasia. The work of flexion, tendon gliding resistance, and adhesion score in treated tendons were significantly less than the untreated tendons (p < 0.05). The failure strength of the untreated tendons was higher than the treated tendons at 21 and 42 days (p < 0.05). However, there is no significant difference in stiffness between two groups at day 42. Histologic analysis of treated tendons showed a smooth surface and viable transplanted cells 42 days after the repair, whereas untreated tendons showed severe adhesion formation around the repair site. The combination of lubricant and cell treatment resulted in significantly improved digit function, reduced adhesion formation. This novel treatment can address the unmet needs of patients who are unable to commence an early mobilization protocol after flexor tendon repair.

Keywords: bone marrow stromal cells, flexor tendon, hyaluronic acid, immobilization, lubricin, tendon repair

Flexor tendon injury is one of the most common hand traumas.1,2 The standard of care is primary repair immediately after tendon injury and then early mobilization to reduce postoperative adhesions, the most common complication that hinders hand function.2–4 However, prompt rehabilitation may not always be possible, because of associated injuries that require postoperative immobilization, such as fractures, vascular, and nerve injuries, or because of the patient’s inability to cooperate with the mobilization protocol, as may occur in children or in adults with mental impairment due to injury or disease.5–9 In such circumstances, the immobilization phase must be prolonged, which often results in poor tendon function or necessitates a second surgery for tenolysis.4,9,10 A treatment that allows an extended initial period of tendon immobilization while minimizing adhesion formation could have significant clinical importance.

Recent experimental studies have shown that adhesion formation is significantly decreased if the repaired tendon is chemically treated with biolubricant compounds, such as hyaluronic acid and lubricin, both of which occur naturally in synovial fluid.11,12 This potential strategy to reduce adhesion formation after tendon repair may also provide an effective treatment for patients who undergo flexor tendon repair but require postoperative immobilization.

In addition to adhesion prevention, intrinsic healing is another challenge after flexor tendon laceration, because these tendons are both hypovascular and hypocellular.13,14 The capacity for intrinsic healing becomes even more critical when extrinsic healing sources are blocked to prevent adhesion formation.11,12 Finally, immobilization itself can impair intrinsic healing, because the pumping of synovial fluid around the tendon is an important source of tendon nutrition, and this source is thus much reduced when the tendon is immobilized.15

Recently, we have explored cell-based therapy, using an interpositional graft of GDF-5 stimulated autologous bone marrow stromal cells to enhance tendon healing, with encouraging results.12,16,17 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of tendon surface modification in combination with cell-based therapy on flexor tendon repair in the clinically relevant scenario of delayed rehabilitation, using a canine in vivo model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Study Overview

We placed 39 mixed-breed dogs into 2 survival groups: 21 days (n = 19) and 42 days (n = 20). Bone marrow was aspirated from both tibias of each dog 3 weeks before tendon surgery. The operated paw was chosen randomly and the second and fifth digits of the selected paw had tendon surgery as described below. At the time of surgery, one digit was randomly selected for the experimental treatment and the other tendon was repaired without any additional treatment. The wrist of the operated paw was immobilized with a Kirschner wire (K-wire) and protected with a custom sling for 21 days. Dogs in the 21-day group were sacrificed before K-wire removal. Dogs in the 42-day group had the K-wire removed under anesthesia on day 21 and then started synergistic wrist and digit motion therapy,18 which continued until sacrifice on day 42. Treated and untreated digits of twelve 42-day animals and eleven 21-day animals were assessed for digit work of flexion, adhesion score, tendon gliding resistance, and tendon failure strength. Six treated and untreated tendons in each group were tested for expression of genes involved in tendon healing and growth by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and two treated and untreated samples in each group were examined histologically.

Fabrication of the Cell-Seeded Gel

Tibial bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were prepared using an established protocol.16 A collagen gel was made with 1 ml PureCol bovine dermal collagen (Inamed Corp., Fremont, CA) that was mixed with 1.5 ml of minimal essential medium (pH 7.4), 6 µl of 1.75 M NaOH, and 0.5 ml distilled H2O. This solution was combined with 3 ml MEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and 2% antibiotics. A 200-µl aliquot of the mixed solution was added to each well of a 48-well dish and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. A 100-µl aliquot of the cell suspension, containing 2 × 105 cells, and recombinant human growth and differentiation factor 5 (rhGDF-5; 100 ng/ml; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were then added to the gels, thus each gel patch contained 30 ng of GDF-5 (200 µl gel + 100 µl cell mixture). Gels were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 1 day for further gelation, after which they were used for the experimental treatment.

Surgical Procedure and Postoperative Care

The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendons were sharply transected at the zone II-D level19 and repaired with a modified Pennington technique using a 4-0 FiberWire suture (Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) reinforced with a running suture of 6-0 Prolene (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ).20 The cell-seeded gel patch after contraction was about 1 mm in diameter. The tendon selected for treatment had four cell-seeded gels (a total of 8 × 105 cells) inserted between the cut tendon ends (two around core suture and two in between) after core suture placement and before tying the suture with a two-strand overhand locking knot.21 After completion of the repair, the treated tendon surface was coated with carbodiimide-derivatized hyaluronic acid, gelatin, and bovine lubricin (cd-HA-lubricin), using a formula previously reported.11 After tendon repair, a radial neurectomy was performed at the proximal humerus level to paralyze the elbow and wrist extensors and thus preclude weight-bearing on that limb.22 The operated wrist was immobilized in 90° of flexion with a threaded, 1.6-mm diameter K-wire passing from the distal radius to the proximal third metacarpal bone. After surgery, dogs were dressed in custom jackets that immobilized the operated paw in front of the chest. On postoperative day 21, 19 dogs were euthanized. The remaining 20 dogs underwent K-wire removal and started wrist and digit synergistic therapy for 21 additional days; they were euthanized on postoperative day 42.

Biomechanical Evaluation

Immediately after the dogs were sacrificed, the paws were tested for digit work of flexion, which was then normalized by digit joint motion (nWOF), using a well-established protocol.23 After nWOF testing, the digits were carefully exposed at the repair site and adhesions were scored using four categories: none, mild, moderate, or severe, according to previously established criteria.18 After adhesion evaluation, the repaired tendons were isolated, and gliding resistance was measured between the repaired tendon and its proximal pulley, also as previously described.24 Finally, the mechanical strength of the repaired tendon was measured. An additional eight canine FDP tendons from the contralateral, unoperated paws were lacerated and repaired with the same technique to provide baseline (time zero) data.

Gene Expression by RT-PCR

Expression of genes encoding type I collagen, type III collagen, tenomodulin, fibronectin, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) was analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR.25 These gene products are involved in tenogenesis: type I and III collagens are structural products needed for tendon healing,26 tenomodulin is a tenocyte-specific marker,27 and fibronectin and TGF-β are biomarkers for cellular activity associated with wound healing.28 Briefly, a 20-mm segment of the repaired tendon, centered on the repair site, was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after harvesting and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. RNA was purified with miRNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and analyzed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using random primers with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche) was used for RT-PCR. The target sequences and a constitutively expressed housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH),29 were amplified simultaneously using the primer sequences reported in previous studies.25,30

Cell Tracking and Histology

Two tendons in each group were used for tracking BMSC viability, 21 or 42 days after the repair, based on our previous protocol.17 Briefly, BMSCs were labeled with Vybrant DiI cell-labeling solution (Molecular Probes, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions before seeding into the gels. Gels with labeled cells were placed between the cut tendon ends during repair, as described previously.12 Tendons were harvested immediately after sacrifice. Tendons were observed with a confocal microscope (LSM510; Zeiss). After cell retention was evaluated, the tendons were fixed with a 10% formalin solution, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 7-µm-thick slices. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and qualitatively observed using light microscopy.

Statistical Analysis

Incidence of gap formation and repair rupture, as well as adhesion scores, was analyzed with the Fisher exact test. Quantitative data (normalized work of flexion, gliding resistance, repair strength, gene expression) are presented as mean (SD). Treated and untreated tendons were analyzed with a paired t test at each time point because different digits within a single paw were assessed. One-way analysis of variance was used to test differences among the two time points because comparisons were made among different dogs. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Inc.).

RESULTS

In treated tendon groups, two repaired tendons in the 21-day group had gap formation, and 2 in the 42-day group ruptured. In untreated groups, three repaired tendons in the 21-day group had gap formation and no ruptures were observed at either time point. The Fisher test did not show any significant difference in gap or rupture rate among groups (Table 1). Gross observation in treated tendons revealed less adhesion formation, with smoother tendon surfaces compared to the untreated repaired tendons in both the 21- and 42-day groups (Fig. 1). Adhesion scores are shown in Table 2; the total number of tendons with adhesions was significantly higher in the untreated group than the treated group at both time points (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Repaired Tendon Gap Formation and Rupture in Each Group

| Untreated Tendon, No. | Treated Tendon, No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | 21 d (n = 19) |

42 d (n = 20) |

21 d (n = 19) |

42 d (n = 20) |

| Gap | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Rupture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Figure 1.

Gross observation after dissection of the repaired tendon. Treated repairs showed smooth tendon surfaces without adhesion at days 21 (A) and 42 (C). Untreated repairs showed adhesions (arrows) around the repair site at days 21 (B) and 42 (D).

Table 2.

Repaired Tendon Adhesion in Each Group

| Untreated Tendon, No. (%) | Treated Tendon, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion Score | 21 d (n = 19) | 42 d (n = 20) | 21 d (n = 19) | 42 d (n = 18*) |

| None | 9 (47) | 2 (10) | 17 (89) | 10 (56) |

| Mild | 4 (21) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 6 (33) |

| Moderate | 6 (32) | 13 (65) | 1 (5) | 2 (11) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

2 ruptured tendons in this group were excluded for adhesion evaluation.

The nWOF of treated tendons was significantly lower than that of the untreated tendons at both 21 and 42 days (Fig. 2A; p < 0.05). In addition, nWOF significantly increased with time in the untreated tendons (p < 0.05), but not in the treated tendons. The gliding resistance was significantly lower in treated tendons than untreated tendons at both 21 and 42 days (p < 0.05; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Normalized work of flexion (A) and repaired tendon gliding resistance (B) studies showed improved digit function and gliding ability in treated tendons. Groups with different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

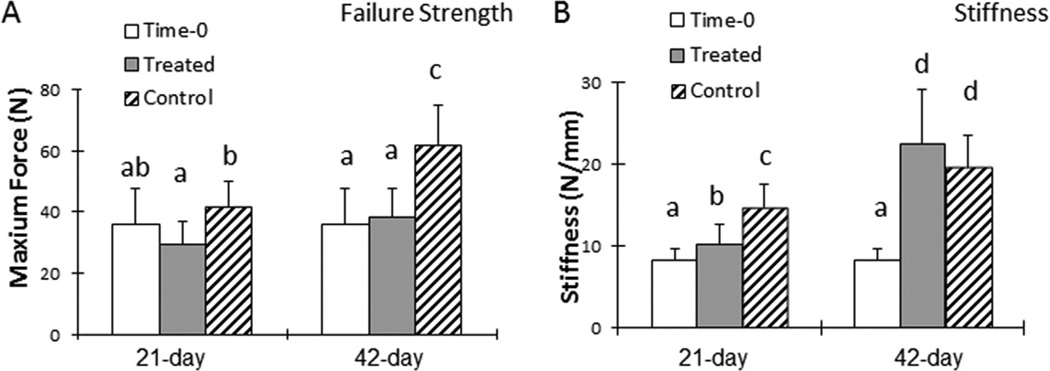

The failure strength of untreated tendons was significantly higher than that of treated tendons at both 21 and 42 days (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Failure strength was not significantly different between the repaired tendons at time zero and the treated tendons at either days 21 or 42. Tendon stiffness was significantly higher in untreated tendons than treated tendons at day 21 (p < 0.05), but no differences were observed by day 42 (Fig. 3B). The stiffness of both treated and untreated tendons at days 21 and 42 was significantly higher than the repaired tendons at time 0 (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Maximum failure strength of repaired tendons was lower in treated tendons versus untreated tendons (A); this difference might be attributable to excessive adhesions in untreated tendons. However, stiffness was similar between treated and untreated repaired tendons on postoperative day 42 (B). Groups with different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05), for example, a < b < c < d.

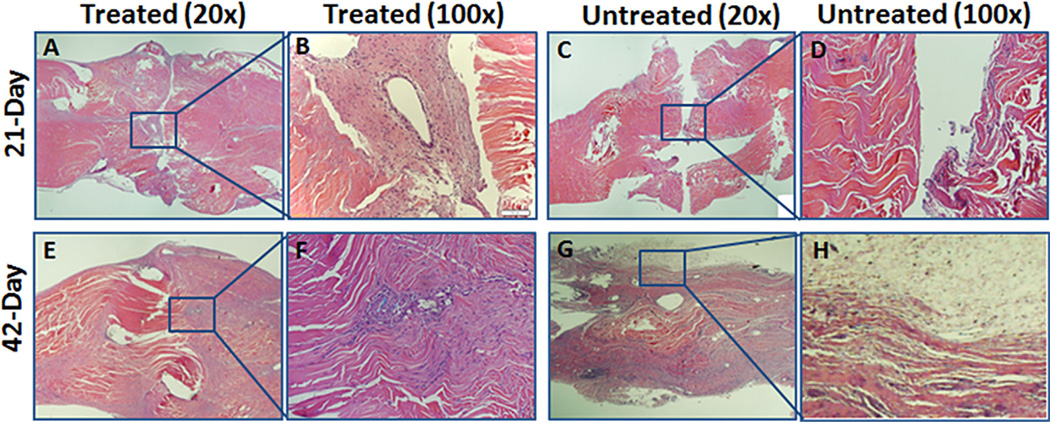

There was no significant difference in gene expression for type I collagen, type III collagen, tenomodulin, fibronectin, or TGF-β when comparing treated and untreated tendons at either time point. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a gap between the repaired tendon ends in both treated and untreated tendons at 21 days. The treated tendon at 21 days showed the cell-gel structure with many cells around the suture (Fig. 4A and B), whereas fewer cells were seen at the repair site in the untreated group (Fig. 4C and D). At 42 days, both the treated and untreated tendons evaluated by histology appeared to heal without a gap at the repair site; however, treated tendons showed a smooth surface without extrinsic adhesions (Fig. 4E and F), while untreated tendons showed severe adhesions around the repair site (Fig. 4G and H). With confocal microscopy, transplanted cells (indicated by red fluorescence) were observed around the repair site in treated tendons at 21 and 42 days (Fig. 5). No red fluorescence was seen in the untreated tendons.

Figure 4.

Histology (hematoxylin and eosin) showed a viable cell-seeded patch on postoperative day 21 at the lacerated tendon ends (A and B), but acellular features at the repair site were noted in untreated tendons (C and D). After 42 days, lacerated tendon ends were fused in treated and untreated tendons (E and G). Treated tendons had a smooth surface at the repair site (E and F), but untreated tendons had abundant adhesions at the repair site surface (G and H).

Figure 5.

Transplanted cells labeled with Vybrant DiI cell tracking solution (red fluorescence) were observed at the repair site of the treated tendons (A, 21 days; C, 42 days). Untreated tendons were negative for fluorescence under confocal microcopy (B and D).

DISCUSSION

For more than a century, flexor tendon injures and their treatment have been considered an important research topic in both clinical and experimental settings because of the high complication rate after surgical repair.31–34 The two major complications after repair are postoperative adhesions and failure of the repair, and preventing these complications is a key step toward improving functional outcomes.35

Three fundamental biomechanical factors affecting clinical outcomes have been identified: repair strength, repair gliding ability, and postoperative rehabilitation.36–38 Balancing these factors is challenging and critical. Rehabilitation that begins early and encourages tendon gliding is essential to a good function result.18,39 The repair must be strong enough to overcome forces applied to the tendon during rehabilitation, thereby avoiding gap or rupture. In addition, the repaired surface must be smooth enough to allow gliding during rehabilitation, thereby eliminating adhesion formation. To meet these two requirements, and thus enable successful rehabilitation, modern repair techniques have attempted to match high repair strength with low gliding resistance,20,40–42 but with limited success, due to weakness at the suture-tendon interface and roughness of the repair site.43,44 Surface modification with lubricating molecules can help to improve repair gliding ability and prevent adhesions,45,46 but this encouraging finding is tempered somewhat by an associated problem of delayed tendon healing.11 Recently, cell-based therapy to enhance tendon intrinsic healing has been added to this model, with promising results.12

Two major clinical factors influence decisions regarding surgical procedures and postsurgical care after flexor tendon injury: one is the patient’s ability to cooperate with postoperative rehabilitation and the other is the nature of the tendon injury and any associated conditions that may interfere with that rehabilitation as well. In clinical scenarios where the repaired tendon must be immobilized postoperatively for reasons either related to patient ability to cooperate or to the nature of the injury, outcomes are predictably poor. To address the challenges of these relevant and important clinical scenarios, we assessed immobilized flexor tendon repairs after surface modification treatment with cd-HA-lubricin plus a GDF-5 stimulated BMSC autograft. Our findings showed that this combination treatment effectively decreased adhesions and improved digit function after 21 days of immobilization. Although failure strength was lower in treated tendons, the stiffness was significantly higher in the treated tendons than the repaired tendons at time 0, indicating that at least some healing had taken place. Histologically, the cell-gel structure was visible at day 21 but had fused with the tendon by day 42. Although untreated repaired tendons had also healed after 42 days, severe adhesions were evident. The abundant adhesions might have contributed to the increased strength of the repaired tendon, but this enhancement would be clinically negated by the impaired tendon motion that would result. Transplanted cells were still viable 42 days after surgery. No differences were observed between treated and untreated tendons in the expression of genes associated with tenogenesis and wound healing, but this may be attributable to the relatively long period after cell transplantation and the mixed population of transplanted cells and local host tenocytes which contributed the RNA for the analysis.

The concept of using GDF-5 was that the GDF-5 would aid in the differentiation of the grafted cells, and not that it would have an effect on the host tendon, as noted also in our previous work.17 However, since we did not study the effect of the cells and GDF-5 independently, we do not know the effect of the GDF-5 alone. Although the failure strength of repaired tendon was still lower in treated tendons compared to the control, the tendon gap and rupture rate was the same between two groups. We believe this clinically relevant observation is more important, and could reflect, for example, enhanced collagen maturation and crosslinking in the treated tendons, which could be due either to the cells, the GDF-5, or both. Unfortunately, in the study design we had not included a measure of collagen crosslinking.

We acknowledge several limitations in the current study. First, neither the surface treatment nor the cell-seeded patch was studied independently. However, a previous report on surface treatment alone showed impaired tendon healing.11 Therefore, the combination of surface and cell treatment was applied as a package, with the intent of improving tendon function and healing. Second, the effect of transplanted cell number was not studied due to limit animal number for this study, and also the viable transplanted cells were not quantified, since only two samples from each group were evaluated with confocal microscopy. Third, we did not normalize the failure strength with the cross-sectional area of the repaired tendon. Therefore, we could not draw definitive conclusions about healing quality, especially for repairs with extensive adhesions. However, because the dogs were all of similar size and weight, it is likely that such differences would be small, and not affect the overall meaning of the results we observed. Finally, the GDF-5 releasing profile was not studied. However, the purpose of using of GDF-5 was to stimulate tenogenic differentiation of the transplanted cells within the gel patch rather than releasing out of the patch to affect the local environment.

In conclusion, the combination of BMSCs, GDF-5, and cd-HA-lubricin treatment for flexor tendons that are immobilized after surgical repair results in significantly reduced adhesion formation and satisfactory tendon healing. Such treatment has clinical relevance because it may address the unmet needs of patients who are unable to commence an early mobilization protocol after flexor tendon repair.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIH/NIAMS; Grant number: AR44391.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Project completion: CZ, YO, HS, RLR, ART, and PCA. Data analysis: CZ, YO, HS, RLR, ART, GJ, SLM, KNA, and PCA. Manuscript writing: CZ, YO, HS, RLR, ART, GJ, SLM, KNA, and PCA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chesney A, Chauhan A, Kattan A, et al. Systematic review of flexor tendon rehabilitation protocols in zone II of the hand. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1583–1592. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d28e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vucekovich K, Gallardo G, Fiala K. Rehabilitation after flexor tendon repair, reconstruction, and tenolysis. Hand Clin. 2005;21:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strickland JW. Results of flexor tendon surgery in zone II. Hand Clin. 1985;1:167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foucher G, Lenoble E, Ben Youssef K, et al. A postoperative regime after digital flexor tenolysis. A series of 72 patients. J Hand Surg Eur. 1993;18:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90192-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vahvanen V, Gripenberg L, Nuutinen P. Flexor tendon injury of the hand in children. A long-term follow-up study of 84 patients. Scand J Reconstr Surg. 1981;15:43–48. doi: 10.3109/02844318109103410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickland JW, Glogovac SV. Digital function following flexor tendon repair in Zone II: a comparison of immobilization and controlled passive motion techniques. J Hand Surg. 1980;5:537–543. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grobbelaar AO, Hudson DA. Flexor tendon injuries in children. J Hand Surg. 1994;19:696–698. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato H, Minami A, Suenaga N, et al. Long-term results after primary repairs of zone 2 flexor tendon lacerations in children younger than age 6 years. J Ped Orthop. 2002;22:732–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez JD, Stern PJ. Complex injuries including flexor tendon disruption. Hand Clin. 2005;21:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strickland JW. Flexor tendon injuries. Part 5. Flexor tenolysis, rehabilitation and results. Orthop Rev. 1987;16:137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao C, Sun Y-L, Kirk RL, et al. Effects of a lubricin-containing compound on the results of flexor tendon repair in a canine model in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1453–1461. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, Ozasa Y, Reisdorf RL, et al. CORR(R) ORS Richard A. Brand award for outstanding orthopaedic research: engineering flexor tendon repair with lubricant, cells, and cytokines in a canine model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2569–2578. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manske PR, Lesker PA. Flexor tendon nutrition. Hand Clin. 1985;1:13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tozer S, Duprez D. Tendon and ligament: development, repair and disease. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today. 2005;75:226–236. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manske PR, Lesker PA. Nutrient pathways of flexor tendons in primates. J Hand Surg. 1982;7:436–444. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao C, Chieh H-F, Bakri K, et al. The effects of bone marrow stromal cell transplants on tendon healing in vitro. Med Eng Phys. 2009;31:1271–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi M, Zhao C, An KN, et al. The effects of growth and differentiation factor 5 on bone marrow stromal cell transplants in an in vitro tendon healing model. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36:271–279. doi: 10.1177/1753193410394521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao C, Amadio PC, Momose T, et al. Effect of synergistic wrist motion on adhesion formation after repair of partial flexor digitorum profundus tendon lacerations in a canine model in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84-A:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amadio PC, Berglund LJ, An KN. Biochemically discrete zones of canine flexor tendon: evaluation of properties with a new photographic method. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:198–204. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka T, Amadio PC, Zhao C, et al. Gliding characteristics and gap formation for locking and grasping tendon repairs: a biomechanical study in a human cadaver model. J Hand Surg. 2004;29:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao C, Hsu CC, Moriya T, et al. Beyond the square knot: a novel knotting technique for surgical use. J Bone Joint Surg. 2013;5:1020–1027. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop AT, Cooney WP, 3rd, Wood MB. Treatment of partial flexor tendon lacerations: the effect of tenorrhaphy and early protected mobilization. J Trauma. 1986;26:301–312. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao C, Amadio PC, Paillard P, et al. Digital resistance and tendon strength during the first week after flexor digitorum profundus tendon repair in a canine model in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86-A:320–327. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An KN, Berglund L, Uchiyama S, et al. Measurement of friction between pulley and flexor tendon. Biomed Sci Instrum. 1993;29:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omae H, Zhao C, Sun YL, et al. The effect of tissue culture on suture holding strength and degradation in canine tendon. J Hand Surg Eur. 2009;34:643–650. doi: 10.1177/1753193409104564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oshiro W, Lou J, Xing X, et al. Flexor tendon healing in the rat: a histologic and gene expression study. J Hand Surg. 2003;28:814–823. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(03)00366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shukunami C, Takimoto A, Oro M, et al. Scleraxis positively regulates the expression of tenomodulin, a differentiation marker of tenocytes. Dev Biol. 2006;298:234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molloy T, Wang Y, Murrell G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med. 2003;33:381–394. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Thoreson A, Cha S, et al. Temporal response of canine flexor tendon to limb suspension. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1762–1768. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00051.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omae H, Steinmann SP, Zhao C, et al. Biomechanical effect of rotator cuff augmentation with an acellular dermal matrix graft: a cadaver study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012;27:789–792. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason M, Allen H. The rate of healing of tendons. An experimental study of tensile strength. Ann Surg. 1941;113:424–459. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194103000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinert HE. Should an incompletely severed tendon be sutured? Commentary. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57:236. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197602000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silfverskiold KL, May EJ, Oden A. Factors affecting results after flexor tendon repair in zone II: a multivariate prospective analysis. J Hand Surg. 1993;18:654–662. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(93)90312-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Putter CE, Selles RW, Polinder S, et al. Economic impact of hand and wrist injuries: health-care costs and productivity costs in a population-based study. J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94:e56. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang JB. Clinical outcomes associated with flexor tendon repair. Hand Clin. 2005;21:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strickland JW. Development of flexor tendon surgery: twenty-five years of progress. J Hand Surg. 2000;25:214–235. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.jhsu25a0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uchiyama S, Amadio PC, Coert JH, et al. Gliding resistance of extrasynovial and intrasynovial tendons through the A2 pulley. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79:219–224. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooney WP, Lin GT, An KN. Improved tendon excursion following flexor tendon repair. J Hand Ther. 1989;2:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelberman RH, Nunley JA, 2nd, Osterman AL, et al. Influences of the protected passive mobilization interval on flexor tendon healing. A prospective randomized clinical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991:189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savage R. In vitro studies of a new method of flexor tendon repair. J Hand Surg. 1985;10:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(85)90001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H. Double loop locking suture. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15:953–958. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90022-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dinopoulos HT, Boyer MI, Burns ME, et al. The resistance of a four- and eight-strand suture technique to gap formation during tensile testing: an experimental study of repaired canine flexor tendons after 10 days of in vivo healing. J Hand Surg. 2000;25:489–498. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao C, Sun Y-L, Zobitz ME, et al. Enhancing the strength of the tendon-suture interface using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride and cyanoacrylate. J Hand Surg (Am) 2007;32:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao C, Amadio PC, Momose T, et al. The effect of suture technique on adhesion formation after flexor tendon repair for partial lacerations in a canine model. J Trauma. 2001;51:917–921. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang C, Amadio PC, Sun YL, et al. Tendon surface modification by chemically modified HA coating after flexor digitorum profundus tendon repair. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;68:15–20. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taguchi M, Sun YL, Zhao C, et al. Lubricin surface modification improves tendon gliding after tendon repair in a canine model in vitro. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:257–263. doi: 10.1002/jor.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]