Summary

A genetic etiology has been identified in 30% to 40% of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients, yet only 50% of these cases are associated with a known causative gene variant. Thus, in order to understand the pathophysiology of DCM, it is necessary to identify and characterize additional genes. In this study, whole exome sequencing in combination with segregation analysis was used to identify mutations in a novel gene, filamin C (FLNC), resulting in a cardiac-restricted DCM pathology. Here we provide functional data via zebrafish studies and protein analysis to support a model implicating FLNC haploinsufficiency as a mechanism of DCM.

Key Words: cardiovascular genetics, dilated cardiomyopathy, filamin C, heart failure, zebrafish

Abbreviations and Acronyms: DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; dpf, days post-fertilization; FLNC, filamin C; flnca, filamin Ca; flncb, filamin Cb; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; hpf, hours post-fertilization; LoF, loss-of-function; MFM, myofibrillar myopathy; MO, morpholino; RF, retrograde fraction; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; SV, stroke volume; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; WES, whole exome sequencing

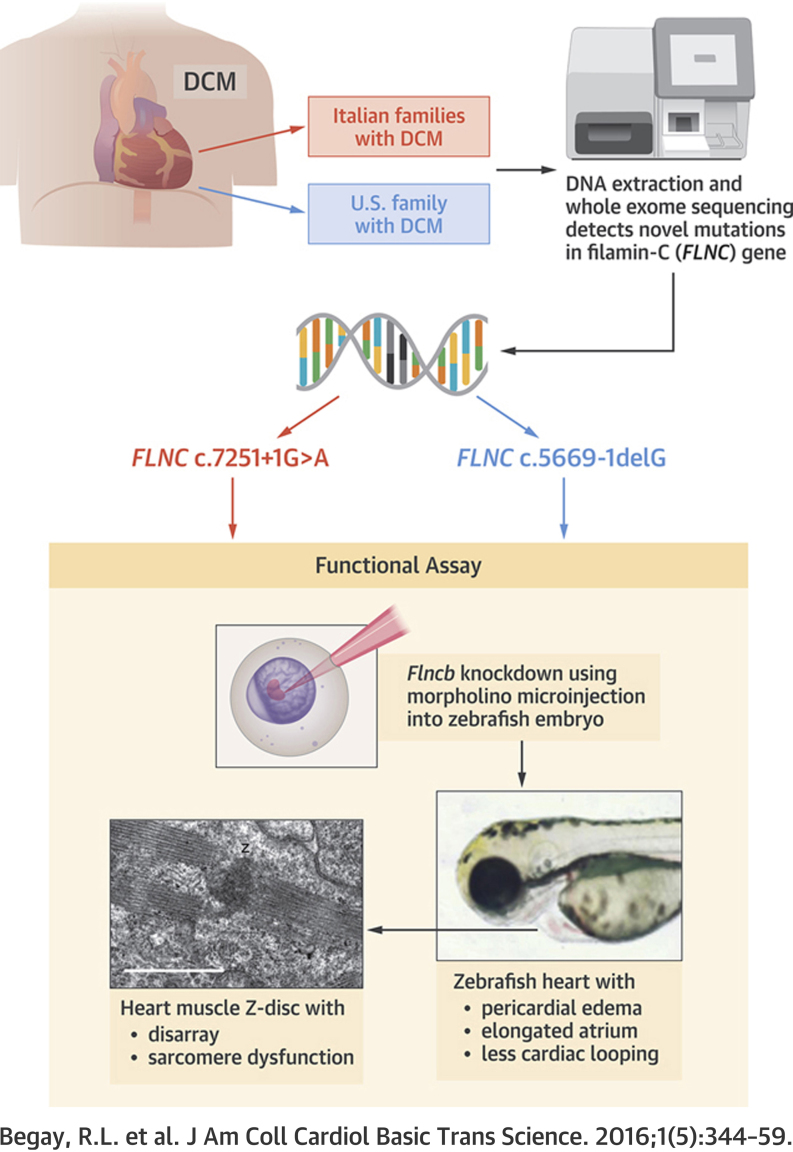

Visual Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Deoxyribonucleic acid obtained from 2 large DCM families was studied using whole-exome sequencing and cosegregation analysis resulting in the identification of a novel disease gene, FLNC. The 2 families, from the same Italian region, harbored the same FLNC splice-site mutation (FLNC c.7251+1G>A).

-

•

A third U.S. family was then identified with a novel FLNC splice-site mutation (FLNC c.5669-1delG) that leads to haploinsufficiency as shown by the FLNC Western blot analysis of the heart muscle.

-

•

The FLNC ortholog flncb morpholino was injected into zebrafish embryos, and when flncb was knocked down caused a cardiac dysfunction phenotype.

-

•

On electron microscopy, the flncb morpholino knockdown zebrafish heart showed defects within the Z-discs and sarcomere disorganization.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a severe disease of the heart muscle characterized by ventricular enlargement and systolic dysfunction leading to progressive heart failure and is among the most common causes of cardiovascular mortality 1, 2. Approximately 30% to 40% of cardiomyopathy cases are familial and attributable to genetic causes (3), and over 30 genes have been shown to cause DCM. However, approximately 50% of DCM cases have unknown causative mutations (4). This apparent gap in our understanding of the disease has prompted ongoing studies to identify additional DCM candidate genes 5, 6.

One such novel candidate gene is filamin C (FLNC), which encodes the structural protein FLNC, an actin-crosslinking protein within the sarcomere of striated muscle. FLNC is located on the chromosome region 7q32–q35 (7). Until recently, deletion/insertion frameshift, point, and nonsense FLNC mutations have only been reported in association with isolated skeletal distal and myofibrillar myopathy diagnoses 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. However, in 2014, Brodehl et al. (13), identified 2 missense variants (p.S1624L; p.I2160F) in 2 families with restrictive cardiomyopathy in the absence of skeletal muscle defects and Valdes-Mas et al. (14) identified several FLNC missense variants (plus 1 stopgain) in several familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) cases. These cardiac-specific studies support FLNC as a candidate gene causing cardiomyopathies and provide evidence that FLNC-related pathology may operate through a variety of mechanisms. The present study reports FLNC mutations in cardiac-restricted DCM, thus adding to the growing evidence supporting a role for the FLNC gene in cardiomyopathy.

In this study, we report the identification of a FLNC splicing variant by whole exome sequencing (WES) in 2 DCM families from the same geographic region of Italy. A second FLNC splicing variant was identified in a U.S. DCM family. All affected family members from each of the 3 families expressed a cardiac-restricted DCM phenotype with no evidence of skeletal muscle involvement. The pathogenic mechanism of these FLNC splicing variants is not definitively elucidated, but reduced cardiac FLNC protein levels in 1 patient is suggestive of a haploinsufficiency model. A haploinsufficiency model is supported by the morpholino (MO) knockdown of the zebrafish FLNC ortholog (flncb) leading to a cardiac-disrupted phenotype.

Methods

Study subjects

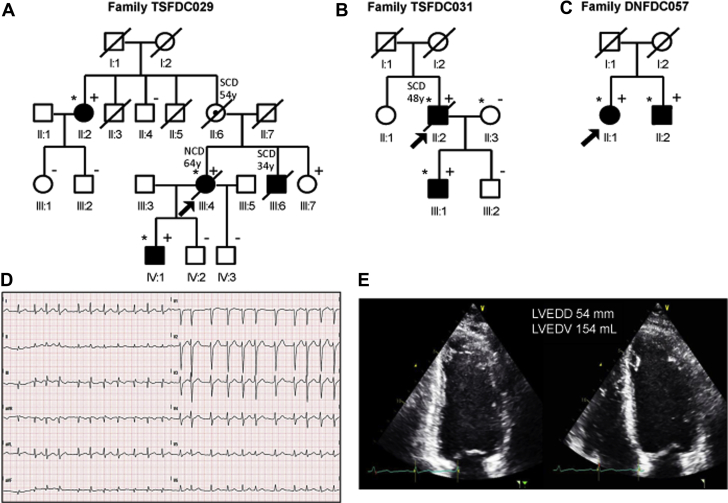

Six individuals from 2 Italian families (Figures 1A and 1B) underwent WES. Two more individuals from a U.S. family (Figure 1C) underwent genetic analysis using Illumina TruSight One Sequencing Panel (San Diego, California), which queries 4,813 genes associated with clinical phenotypes. Families were selected from the Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry, a multicenter, 3-decade-long ongoing project studying human hereditary cardiomyopathies. The diagnosis of DCM was made on the basis of the 1999 consensus criteria of the Guidelines for Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy and evaluation of all available living subjects by investigators (15).

Figure 1.

Family Pedigrees TSFDC029, TSFDC031, and DNFDC057

Squares and circles indicate male and female subjects, respectively, and shading indicates a dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype. The arrowheads indicate probands. Plus and minus signs indicate carriers (+) or noncarriers (–) of the filamin C (FLNC) variant, respectively. Individuals II:2, III:4, and IV:1 in family TSFDC029 (A); individuals II:2, II:3, and III:1 in family TSFDC031 (B); and individuals II:1 and II:2 in family DNFDC057 (C) underwent whole exome sequencing, and are indicated by an ∗. Reported ages at death are indicated. (D) Electrocardiogram of subject TSFDC031 III:1 showing atrial fibrillation, which first occurred at the age of 21 years, and (E) the 2-dimensional echocardiogram images showing a mildly enlarged left ventricle with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% (age 36 years). LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDV = left ventricular end-diastolic volume; NCD = noncardiac death; SCD = sudden cardiac death.

Clinical data collected included medical history, family history, physical examination, and medical data, including laboratory, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram diagnostics (15). Skeletal muscle development was systematically evaluated by a comprehensive physical examination and routine serum creatine kinase testing. Medical records from deceased and living subjects were reviewed when available. Criteria for the diagnosis of DCM were presence of left ventricular fractional shortening <25% and/or an ejection fraction <45%, and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter >117% of the predicted value per the Henry formula (16). Exclusion criteria included any of the following conditions: blood pressure >160/110 mm Hg; obstruction >50% of a major coronary artery branch; alcohol intake >100 g/day; persistent high-rate supraventricular arrhythmia; systemic diseases; pericardial diseases; congenital heart diseases; cor pulmonale; and myocarditis. Informed consent was obtained from all living subjects and local institutional review boards approved the protocol.

Whole exome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted, and WES was performed and analyzed using previous published methods (17). Paired-end sequencing was targeted for a depth of about 100 reads (actual coverage 20× to 64×). The referenced human genome sequence was used in the Genomic Short Read Nucleotide Alignment Program (GSNAP; version 2012-07-20, Thomas Wu/Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, California) (18). Gene lists were initially created for each individual (affected or unaffected) to capture rare heterozygous variants of cardiomyopathy genes, excluding Titin (TTN) missense variants (Supplemental Table 1). Further filtering and annotation were conducted as previously reported (17). Single nucleotide polymorphisms that occurred in <1% in the general population (on the basis of the 1,000 Genomes Project and NHLBI [National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute] GO ESP [Exome Sequencing Project] 19, 20), and were predicted to be damaging in at least 1 of the prediction algorithms, were selected to generate DCM “candidate gene” lists. Finally, Endeavour, a system biology ranking algorithm, was accessed publicly to prioritize the putative disease-causative genes 21, 22 (Supplemental Table 2). The U.S. family DNA samples underwent genetic analysis as directed by the manufacturer using the Illumina TruSight One Sequencing Panel. All candidate gene variants underwent confirmation by Sanger sequencing.

Zebrafish

Male and female wildtype zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained according to standard protocols (23). Fish were cared for in the zebrafish core aquarium at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Center in Aurora, Colorado, and at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colorado. Zebrafish experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado Denver (protocol B-748139(04)01D) in accordance with the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. The zebrafish offspring were bred according to standard protocol (23). Fish were anesthetized using tricaine methanesulfonate (3-amino benzoic acidethylester; Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) at a final concentration of 0.16% in 1 × E3 embryo medium (5 mmol/l NaCl, 0.17 mmol/l KCl, 0.33 mmol/l CaCl, 0.33 mmol/l MgSO4 in H20). Fish were staged between 48 and 72 h post-fertilization (hpf) as previously described (24).

Zebrafish microinjection

The effects of filamin Cb (flncb) knockdown were studied with a targeted MO previously described by Ruparelia et al. (25). Control fish were uninjected zebrafish embryos, 25-N+p53 MO-injected fish (25-N is a 25-base pair oligonucleotide mixture generated from random sequences), and p53 MO-injected zebrafish (26). MO were obtained from Gene Tools (Gene Tools, LLC, Philomath, Oregon) (27). p53 MO (5′-GCGCCATTGCTTTGCAAGAATTG-3′) was coinjected to reduce off-target effects (17). Then, 2 nl of control and flncb MO (250 μmol/l in 1× Danieu solution with 0.5% rhodamine dextran [Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts]) solution were microinjected into the fertilized embryo yolk at the 1 to 2 cell stage. Embryos that did not integrate rhodamine dextran into the chorion by 4 hpf were removed from further analysis. Zebrafish embryos were maintained in 1 × E3 solution at 28.9°C. MO studies were completed over a series of separate experiments and the data were combined.

Cardiac phenotypes were scored at 48 and 72 hpf, and percentage of survival was scored at 7 days post-fertilization (dpf). Positive cardiac phenotype scoring criteria were impaired contraction or ventricle collapse and enlarged atrium or abnormal blood flow, or reduced heart looping. Off-target effects included abnormal neurodevelopment and any abnormalities seen in body parts away from the heart, such as the tail. MO-injected and control embryos were treated with 0.003% (200 μmol/l) 1-phenyl 2-thiourea to inhibit pigmentation and optimize visualization of heart function (28).

cDNA and RT-PCR

Human ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from lymphoblast cells collected from affected patient III:1 and healthy patients III:2 and II:3 (family TSFDC031) and used to generate complementary DNA using Ambion kit Cat #75742 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Human FLNC expression was determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) spanning exon 43 with the following primers: F5′-CCGGCGTGCCAGCCGAGTTCAGCAT-3′ and R5′-GTGTGCTTGTCACTGTCCAGCTCA-3′. PCR conditions were 94°C for 10 min, followed by 14 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 64°C for 1 min (annealing temperature dropped 0.5°C per cycle), then 72°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 54°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 7 min.

Zebrafish RNA was extracted from control and flncb MO-injected fish at 48 hpf with Ambion kit Cat #75742, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primers located in exons flanking the MO target site for flncb were F5′-AGTAACCCCAATGCTTGTCG-3′ and R5′-TGGCTTCAACCACAAAATCA-3′. β-actin levels were used as a control value, as previously described by Ruparelia et al. (25).

Western blot

Heart tissue was obtained from the Adult Cardiac Tissue Bank maintained at University of Colorado Denver. To prepare protein lysates, frozen heart samples were homogenized with 350 μl ice cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (to generate 1 to 5 mg/ml) consisting of 150 mmol/l sodium chloride, 1.0% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate, 50 mmol/l tris pH 7.5, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich); agitated for 2 h at 4°C; diluted in 500 μl 2× Laemmli buffer containing 4% sodium dodecylsulfate, 10% 2-Mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, and 0.125 mol/l tris HCl pH 6.8; centrifuged at 10,000 revolutions/min for 5 min; and the pellet was discarded. Protein content was quantified using a Bio-Rad RC DC Protein Assay Kit (Berkeley, California). Lysates (25 μg total protein per lane) were processed as previously described (29), with the following changes: 4% to 15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast protein polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) were transferred to Immuno-Blot PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) overnight at 4°C and incubated with primary antibodies in tris-buffered saline tween-20 with 3% milk overnight at 4°C using polyclonal rabbit anti-FLNC C-terminus (HPA006135, 1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), polyclonal rabbit anti-FLNC N-terminus (ARP64454_P050, 1:1,000; Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, California), and monoclonal mouse anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase–peroxidase antibody (G9295, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich). The membrane was probed with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary anti-immunoglobulin G goat antirabbit antibody (A0545, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich) in tris-buffered saline tween-20 with 1% milk and signal visualized using WesternBright ECL HRP detection kit (Advansta, Menlo Park, California).

Zebrafish heart function analysis

The effects of MO injection on cardiac morphology were observed in transgenic Tg(myl7:GFP) embryos that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the cardiac-specific myl7 (formerly cmlc2) promoter, which enables visualization of cardiac morphology (30).

Zebrafish embryos were imaged with a high-speed camera (Photron Fastcam SA3) attached to a bright field stereomicroscope. Videos 1, 2, and 3 were acquired at 1,500 frames/s with a resolution of 1,310 pixels/mm. As previously described (31), spatiotemporal plots were extracted from video sequences and used to calculate blood velocity and the diameter of the atrioventricular junction orifice. Flow rate curves over the cardiac cycle were obtained by multiplying the instantaneous mean blood velocity by the instantaneous mean-cross-sectional atrioventricular junction orifice (assumed to be circular). Stroke volume (SV) (representing the net volume of blood pumped to the body per cardiac cycle) was found by integrating the instantaneous flow rate curve over an entire cardiac cycle. Cardiac output represents the SV times the heart rate. The retrograde (reverse) fraction or flow (RF) describes the portion of total blood that moves in the reverse direction through the atrioventricular junction over the course of 1 cardiac cycle and was calculated as a ratio of the volume of retrograde-moving blood divided by the volume of forward-moving blood 31, 32.

Transmission electron microscopy

Flncb+p53 MO-injected embryos and uninjected control embryos were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as described elsewhere (33). Silver to pale-gold sections (60 to 90 nm) were cut using a diamond knife on a Reichert Ultracut E ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany) and mounted on formvar-coated slot grids. Sections were post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed under a JEOL JEM-1400 TEM (Peabody, Massachusetts) operated at 100 kV.

Statistical analysis

In experiments determining heart rate, SV, cardiac output, and RF, normality was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Levene mean test was used to assess equal variance if data were normally distributed. If data were not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was performed without data transformation. Analysis of parametric data was performed with analysis of variance. Multiple comparisons were performed using either of the following methods: Tukey test or Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. All analyses were performed with SigmaPlot software (version 12.0, Systat Software, San Jose, California). At 72 hpf and 7 dpf, zebrafish cardiac phenotypes and survivors were analyzed using a chi-square test to detect significant differences.

Results

Whole exome sequencing

Members of family TSFDC029 were clinically characterized (Table 1), and 3 affected individuals underwent WES (Figure 1A). Upon bioinformatic filtering of identified polymorphisms, and confirmation by Sanger sequencing, an 8-candidate variant list that cosegregated in the 3 affected individuals was generated (Supplemental Table 2). Further cosegregation analysis using samples from unaffected subjects was used to exclude variants that were present in 2 or more unaffected family members. All variants were excluded except FLNC c.7251+1 G>A (NM_001458). This variant was found to be absent from the 1,000 Genomes Project, GO ESP database, and ExAC (Cambridge, Massachusetts) (34). The variant was present in all affected relatives and was missing from 3 of the 4 unaffected family members. The clinically unaffected variant carrier, individual III:7, was enrolled at age 34 years with a history of palpitations and an unremarkable echocardiogram; she declined any further clinical follow-up. Of the variants excluded because of lack of cosegregation, only ANK2 was associated with a cardiac phenotype (long QT syndrome). However, the affected family members did not show any change of QT interval.

Table 1.

Phenotype Characteristics of DCM-Affected Individuals and FLNC-Variant Carriers in Families TSFDC029, TSFDC031, and DNFDC057

| Individual |

Age at Enrollment, yrs |

Sex |

Symptoms |

Arrhythmias |

ECG |

NYHA |

LVEF (%) |

LVEDD (cm) |

FS (%) |

CK |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSFDC029 | |||||||||||

| II:2 | 62 | F | Palpitations | SVT, PVC (800/24 h), NSVT | PVC | I | 52 | 5.4; infero-basal hypokinesis | 24 | 56 | 77 yo, NYHA I, LVEF 51% |

| III:4 | 46 | F | Palpitations, SOB, chest pain |

PVC (900/24 h), NSVT | Low voltages | II | 32 | 5.5 | 20 | 32 | 59 yo, NYHA II noncardiac death |

| III:6∗ | 35 | M | Asymptomatic | — | — | I | — | — | — | — | 34 yo, SD, cardiomegaly |

| III:7 | 34 | F | Palpitations | No | Normal | I | 63 | 4.9 | 31 | 50 | — |

| IV:1 | 27 | M | Fatigue, palpitations | PAC, PVC (93/24 h) | RBBB | II | 45 | 5.3 | 26 | 80 | 41 yo, NYHA I, palpitations LVEF 52% |

| TSFDC031 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II:2 | 44 | M | SOB | 154/24 h, couplet, NSVT | Normal | II | 47 | 5.7 | 17 | 103 | 48 yo, NYHA II SD |

| III:1 | 20 | M | Pre-syncope | PAFib, SVT, SAECG | Normal | I | 45 | 55, infero-basal hypokinesis | 23 | 70 | 36 yo, NYHA I, palpitations, LVEF 40% |

| DNFDC057 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II:1 | 53 | F | Palpitations, SOB | pVT (1997) Afib | LVH | II | 10 | 5.6 | — | 106 | OHT |

| II:2 | 59 | M | DOE, fatigue | PVC | AVB1, inc. LBBB | III | 45 | 6.4 | 24 | 118 | LVEF 21% |

Dashes indicate unavailable data.

AF = atrial fibrillation; AVB = atrioventricular block; CK = creatine kinase; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; DOE = dyspnea on exertion; ECG = electrocardiogram; FLNC = filamin C; FS = fractional shortening; inc. = increase; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; NSVT = nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA = New York Heart Association functional class; OHT = orthotopic heart transplant; PAC = premature atrial contractions; PAF = paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; PVC = premature ventricular contractions; pVT = polymorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia; RBBB = right bundle branch block; SAECG = signal-averaged electrocardiography; SD = sudden unexpected death; SOB = shortness of breath; SVT = supraventricular tachycardia; yo = years old.

Individual III-6 died before enrollment; deoxyribonucleic acid was not available for genetic testing.

Family TSFDC031 (Figure 1B) also underwent WES and yielded >40 variants after bioinformatic filtering. The identical FLNC c.7251+1 G>A splicing variant was detected and no other obvious candidate DCM genes were identified. Although family structures of TSFDC029 and TSFDC031 did not allow formal haplotype analysis, we were able to analyze nearby genotypes that showed consistency with a shared ancestral haplotype.

Family DNFDC057 (Figure 1C) underwent genetic analysis by the Illumina TruSight One Sequencing Panel. A FLNC splicing variant (c.5669-1delG; NM_001458) was detected in the proband as well as affected relative II:2. This variant was found to also be unique (absent from ExAC, the 1,000 Genomes Project, and GO ESP databases).

FLNC phenotype among patients

The phenotypes of all affected DCM subjects were cardiac-isolated with no evidence of skeletal muscle disease or creatine kinase elevation (Table 1). All 3 families were characterized by a strong arrhythmogenic trait.

In family TSFDC029, individuals II:6 and III:6 died of sudden unexpected cardiac deaths at the ages of 54 and 34 years, respectively. Individual III:6 was found post-mortem to have cardiomegaly. The proband (III:4) died of noncardiac causes at age 64 years, but exhibited frequent (>40/h) and repetitive premature ventricular contractions in the absence of heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class II). A second-degree relative (II:2) and the proband’s son (IV:1) had evidence of mild DCM. As described, the proband’s sister (III:7) did not meet DCM criteria at the time of evaluation, having normal ventricular function and dimensions, but she was symptomatic for palpitations. Among family TSFDC031, the proband (II:2) had a history of well-compensated DCM and died of sudden unexpected death at the age of 48 years. His son (III:1) exhibited supraventricular arrhythmias (recurrent atrial fibrillation and atrial tachycardia) before showing DCM with mild left ventricular dysfunction (Figures 1D and 1E). Overall, the rare FLNC variant in the 2 families was 83% penetrant, with sudden death occurring before the age of 55 years in 3 of 8 known or suspected carriers (38%).

In the third family, DNFDC057, the proband (II:1) presented at the age of 46 years with polymorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and was found to have DCM with severe left ventricular dysfunction. After an initial improvement with medical therapy, she deteriorated and was transplanted at the age of 60 years. Her brother (II:2) presented at the age of 53 years with severe left ventricular dysfunction and frequent premature ventricular contractions. Cardiac function improved with medical therapy, but then progressively worsened, leading to him being listed for a left ventricular assist device.

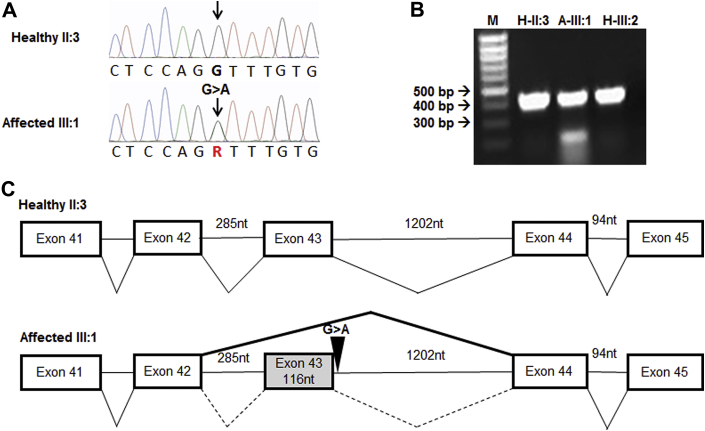

FLNC transcript characterization and western blot

The FLNC variant in families TSFDC029 and TSFDC031 results in a G>A nucleotide transition and is predicted to remove the splice donor site for intron 43 (Figures 2A and 2C). RT-PCR revealed a single 409 base pair fragment spanning exons 41 to 45 in healthy individuals (from family TSFDC031, II:3 and III:2) and an additional 293 base pair fragment in an affected subject (III:1) (Figure 2B). Sanger sequencing confirmed that this shorter product lacked exon 43, producing a frameshift, which is predicted to result in a premature truncation of the protein 21 amino acids downstream of the mutation site (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Affected Individuals Carry a Mutation at the Intronic Border of Exon 43

(A) Sanger sequenced chromatogram of healthy individual II:3 from family TSFDC031 with a normal FLNC gene and an affected individual from the same family (III:1) showing the FLNC c.7251+1 G>A variant. (B) Real-time polymerase chain reaction of ribonucleic acid isolated from lymphoblastoid human cells for exons 41 to 45 spanning probe showing presence of shortened product (missing 116 nucleotides, exon 43) in an affected patient (A-III:1) and normal product in healthy relatives (H-II:3 and H-III:2). (C) Diagram of normal (upper) and aberrant (lower) splicing; thick, solid line (lower) shows exon 43 being excluded. bp = base pair; nt = nucleotide.

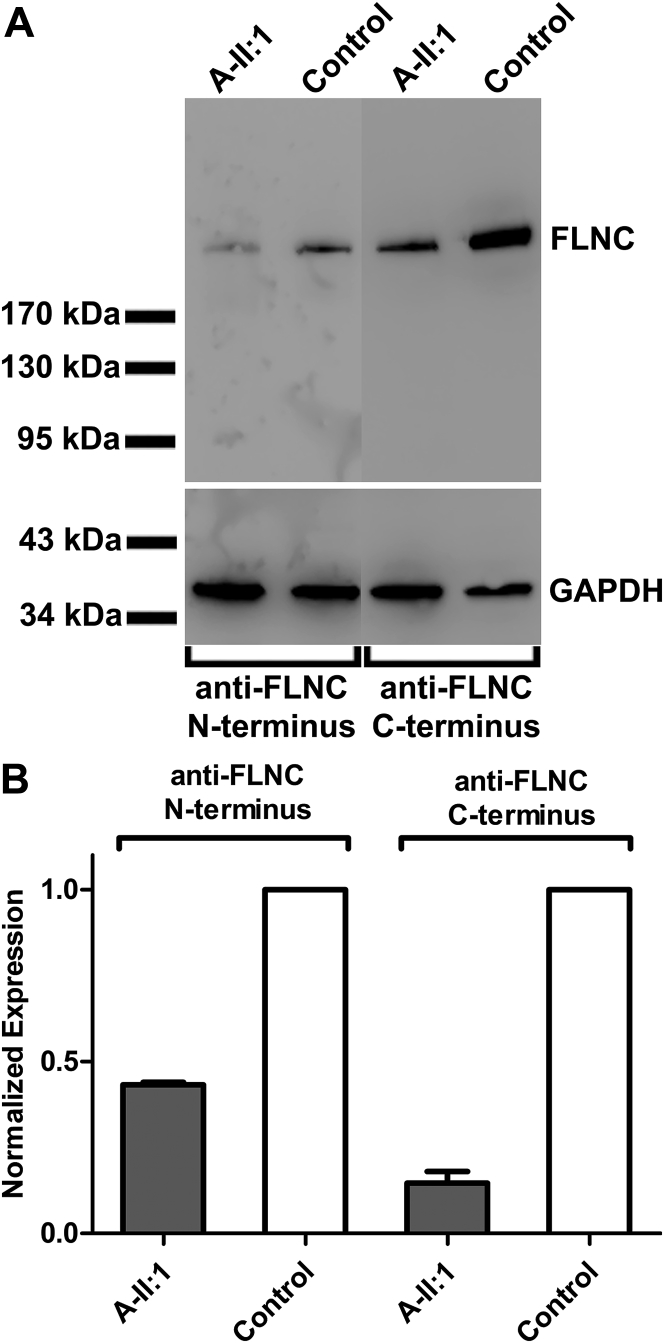

Cardiac tissue allowed for RNA and protein isolation from DNFDC057 affected proband II:1, which showed decreased FLNC RNA expression (data not shown) and reduced FLNC protein (Figures 3A and 3B) when compared with a control sample.

Figure 3.

FLNC Cardiac Protein Expression Is Decreased

(A) Western blot analysis shows decreased FLNC protein expression in affected individual II:1 (A-II:1) from family DNFDC057, and (B) analysis of densitometry of Western blots of affected subject A-II:1 relative to control subjects were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) ± SEM (n = 2).

Zebrafish flncb gene

To further characterize FLNC and its functional role in causing the DCM phenotype, we studied the zebrafish FLNC ortholog flncb. The FLNC gene is duplicated in the zebrafish genome (flnca and flncb), and the flncb gene was chosen for analysis on the basis of its greater sequence similarity to the human FLNC gene than the zebrafish ortholog flnca (25). Successful knockdown of flncb using the splice site flncb MO was confirmed by RT-PCR (Supplemental Figure 2). RT-PCR in flncb MO-injected embryos indicated a loss of normally spliced flncb messenger RNA, but detected the presence of multiple different-sized product bands consistent with abnormal splicing. Abnormal splicing in MO-injected embryos was confirmed by sequencing the most prominent band (Supplemental Figure 2, arrow).

Zebrafish cardiac phenotype

Zebrafish embryos injected with flncb MO showed more frequent cardiac phenotypes and reduced survival (Supplemental Figure 3) when compared to control embryos. Fewer than 25% of flncb MO-injected zebrafish embryos without p53 MO exhibited 1 or more of the following phenotypes: death in the central nervous system, less distinct morphology of the brain ventricles, notochord defects, and body length defects (data not shown). These phenotypes are consistent with previously described off-target defects associated with ectopic up-regulation of the p53 pathway caused by MO injection in general (35). Note that flncb is not expressed in the brain or notochord. Indeed, the incidence of these phenotypes was markedly reduced in embryos coinjected with p53 MO.

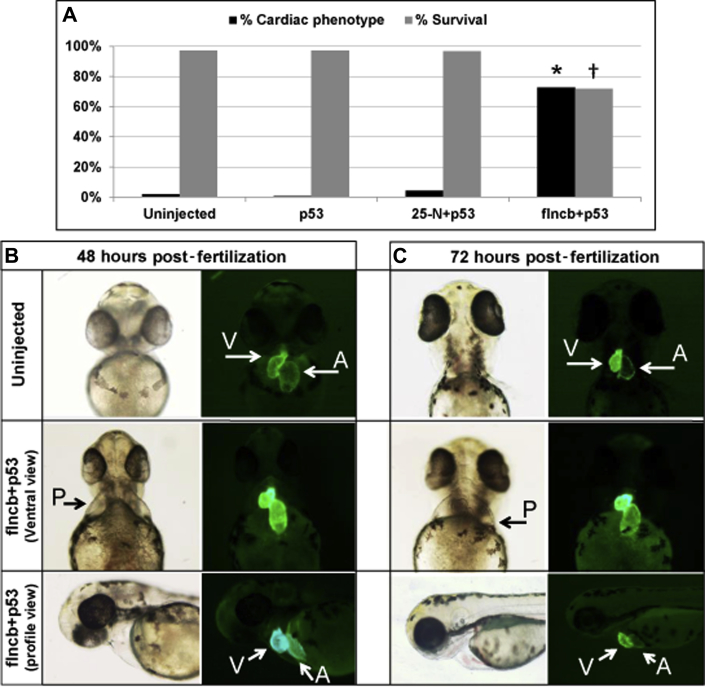

Injection of flncb+p53 MO led to a significantly greater number of embryos displaying a cardiac phenotype when compared with control embryos (uninjected, p53 MO, and scrambled 25-N+p53 MO) (percentage of embryos with a cardiac phenotype and sample size at 72 hpf: uninjected = 1.95%, n = 411; p53 control-injected embryo = 0.72%, n = 139; 25-N+p53 control-injected embryo = 4.27%, n = 351; flncb+p53 MO-injected = 72.61%, n = 241; p = 1.04 × 10-83 for comparison of uninjected versus flncb+p53 MO) (Figure 4A). In addition, survival at 7 dpf among the flncb MO-injected embryos was significantly lower than for control embryos (percentage of survival at 7 dpf relative to sample size on day 0: uninjected = 97.08%, n = 411; p53 control-injected embryo = 97.12%, n = 139; 25-N+p53 control-injected embryo = 96.58%, n = 351; flncb+p53 MO-injected embryo = 71.95%, n = 164; p = 1.65 × 10-19 for comparison of uninjected versus flncb+p53 MO) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

MO Knockdown of flncb in Zebrafish Showing a Cardiac Phenotype

(A) Black bars: percentage of surviving embryos with severe cardiac phenotype at 72 h post-fertilization (hpf) for uninjected (n = 411), p53 morpholino (MO)-injected (n = 139), 25-N+p53 control MO-injected (n = 351), and filamin Cb (flncb)+p53 MO-injected (n = 241); *p = 1.04 × 10-83 (for comparison of uninjected heart vs. flncb+p53 MO using chi-square testing). Gray bars: percentage of surviving embryos at 7 days for uninjected (n = 411), p53 MO-injected (n = 139), 25-N+p53 control MO-injected (n = 351), and flncb+p53 MO-injected (n = 164); †p = 1.65 × 10-19 (for comparison of uninjected embryo vs. flncb+p53 MO using chi-square testing). (B) Representative zebrafish heart pictures for embryo uninjected and flncb MO coinjected with p53 MO zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf. The flncb+p53 MO-injected zebrafish show cardiac phenotype (pericardial edema [P]), and GFP hearts showing less heart looping, elongated atrium, pericardial edema, and a truncated ventricle. (C) Representative zebrafish heart pictures for embryo uninjected and flncb MO coinjected with p53 MO zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf. Among the flncb+p53 MO-injected zebrafish, they show cardiac phenotype, and GFP hearts further show less heart looping, elongated atrium, pericardial edema, and a truncated ventricle.

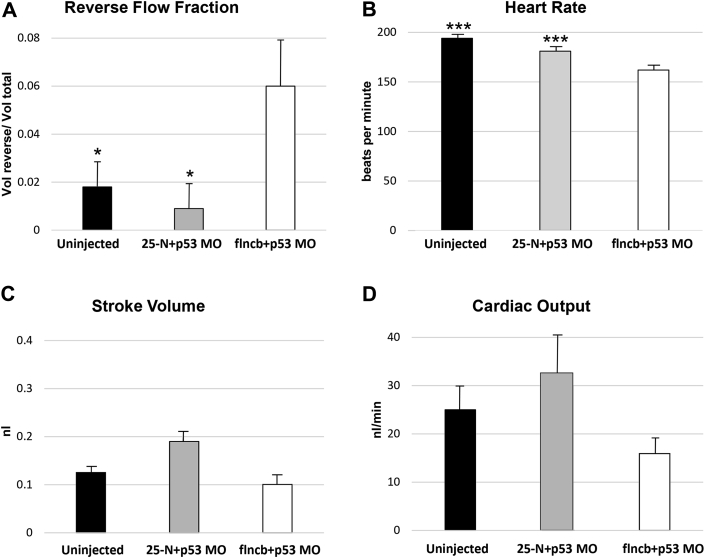

The transgenic GFP-injected flncb+p53 MO zebrafish embryos at 48 and 72 hpf demonstrated pericardial edema, dysmorphic or dilated cardiac chambers, and abnormal looping of the heart tube suggestive of systolic dysfunction (Figures 4B and 4C). By 48 hpf, 9% of flncb+p53 MO lacked circulation entirely, indicating a functional cardiac defect. The remaining 91% had varying degrees of reduced blood circulation, accompanied by an increase in retrograde blood flow and overall weaker contractility. Heart function in the latter group was assessed by video analysis (Videos 1, 2, and 3), which indicated that the mean RF was significantly increased in flncb+p53 MO embryos (0.061) relative to uninjected control embryos (0.017) and 25-N+p53 MO control embryos (0.008) (Figure 5A). RF and heart rate were normally (Gaussian) distributed according to the Shapiro-Wilk test: analysis of variance indicated a significant difference among treatments (p = 6.1 × 10-5), and post hoc Tukey test indicated that flncb+p53 MO embryos demonstrated significant differences in RF by 48 hpf relative to both uninjected embryos and 25-N+p53 MO-injected embryos (p = 0.023 and p = 0.007, respectively), whereas the 2 control embryos were not different from each other (p = 0.420). In addition, heart rate was slower in flncb+p53 MO embryos relative to both types of control embryos (Figure 5B). SV (p = 0.482) and cardiac output (p = 0.293) were not normally distributed, and in these cases, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Despite cardiac malformation and defects related to patterns of contraction, flncb+p53 MO-depleted embryos were able to maintain normal SV (Figure 5C) and normal cardiac output (Figure 5D) through the first 2 days of development.

Figure 5.

Morphological Analysis Demonstrating Impaired Cardiac Function of flncb+p53 MO-Injected Zebrafish Embryos

High-speed videos of hearts in 48 hpf embryos were analyzed using custom MATLAB software (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts) 23, 24. Embryos injected with flnc+p53 MO (n = 21) were compared with uninjected control embryos (n = 17) and control embryos injected with a scrambled MO (25-N+p53 MO; n = 11). (A) Mean reverse flow fraction (±SE) for each treatment (uninjected: 0.017, 25-N+p53 MO: 0.008, flncb+p53 MO: 0.061). Significant differences were observed for flncb+p53 MO-injected relative to control embryos by analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p = 6.1 × 10-5). Follow-up Tukey tests indicated differences between flncb+p53 MO and uninjected embryos (p = 0.023); and flncb+p53 MO compared with 25-N+p53 MO (p = 0.007), but no difference between the control embryos (p = 0.420). (B) Mean heart rate (±SE) for each treatment (uninjected: 193.5 beats/min [bpm], 25-N+p53 MO: 181.0 bpm, flncb+p53 MO: 162.0 bpm (ANOVA; p = 2.1 × 10-7). flncb+p53 MO decreased the heart rate at 48 hpf compared with both uninjected embryos and 25-N+p53 MO-injected embryos. (***p = 0.001, ***p = 0.005, respectively, by Tukey Test); heart rates of uninjected versus 25-N+p53 MO were not different (p = 0.118). (C) Mean stroke volume (±SE) for each treatment (uninjected: 0.125 nl, 25-N+p53 MO: 0.185 nl, flncb+p53 MO: 0.100 nl). No significant difference was detected between treatments (Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA on ranks; p = 0.482). (D) Mean cardiac output (±SE) for each treatment (uninjected: 24.4 nl/min, 25-N+p53 MO: 32.6 nl/min, flncb+p53 MO: 16.0 nl/min). No significant difference was detected between treatments (Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA on ranks; p = 0.293). For Videos 1, 2, and 3, please see the online version of this article. Abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Ventral view of an uninjected control zebrafish heart at 48 hours post-fertilization.

For online presentation, these supplemental videos have been reduced in resolution and modified to read at 30 frames per second.

Ventral view of a 25N-MO control zebrafish heart at 48 hours post-fertilization.

For online presentation, these supplemental videos have been reduced in resolution and modified to read at 30 frames per second.

Ventral view of a representative flncb MO zebrafish heart at 48 hours post-fertilization.

Note the increased fraction of retrograde flow through the atrioventricular junction. For online presentation, these supplemental videos have been reduced in resolution and modified to read at 30 frames per second.

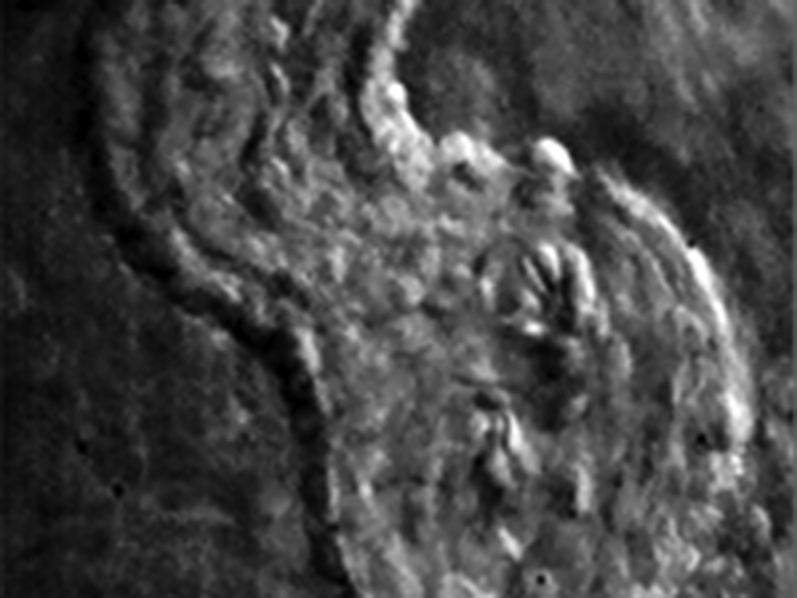

Zebrafish flncb is essential for sarcomeric organization and Z-disc stability

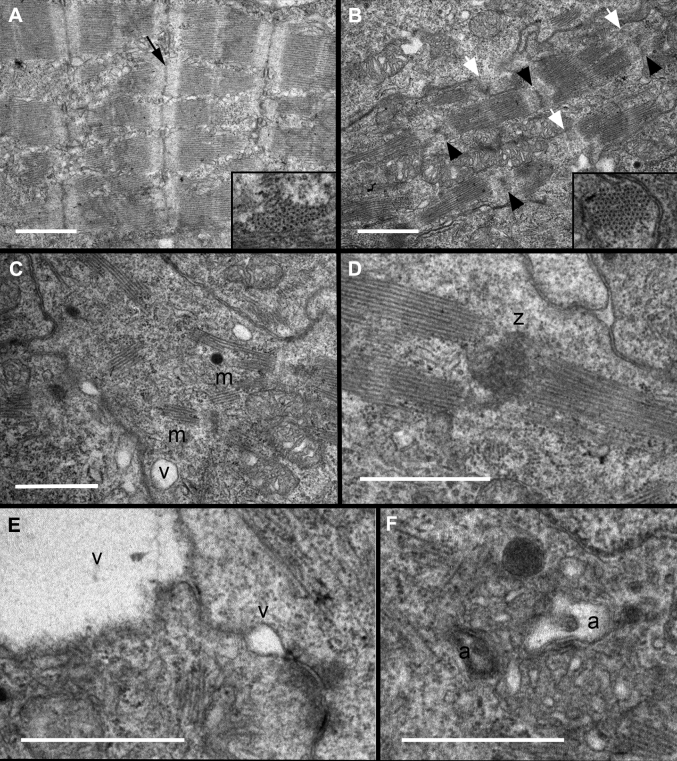

The reduced contractility observed in flncb+p53 MO-injected embryos suggests that the contractile apparatus was abnormal in these hearts. We investigated the role of flncb in sarcomere structure in transverse sections of the zebrafish embryonic ventricle (Figure 6). By 72 hpf, wild-type hearts had assembled arrays of nascent myofibrils composed of consecutive sarcomere units, joined by distinct Z-discs (Figure 6A). In contrast, flncb+p53 MO embryos showed myofibrils composed of fewer consecutive sarcomeres, or myofibrils in abnormal arrangements with Z-discs (Figures 6B to 6D). In most cases, Z-discs appeared irregular or were seemingly absent. However, cross sections revealed that the primary arrangement of thick and thin filaments into hexagonal lattices appears normal, suggesting that initial sarcomerogenesis was normal, but that myofibril growth was impaired. Flncb-depleted cardiomyocytes developed small vacuoles associated with, or near, the cell membrane. In some cases, the vacuoles were quite large (Figure 6E), suggesting that intercellular attachments had ruptured. Potential autophagic vesicles were observed in regions with highly disorganized sarcomeres (Figure 6F). Taken together, these data point to an important role for flncb in maintaining sarcomere stability and cardiomyocyte attachment as mechanical stress increases in the developing embryonic heart.

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural Analysis Indicates Deficiencies in Sarcomere Organization and Z-Disc Formation

Transmission electron micrographs of zebrafish hearts at 72 hpf indicate that (A) wild-type embryos had assembled several consecutive sarcomeres with clearly distinct Z-discs (black arrow), whereas flncb+p53 MO hearts (B to F) show evidence of disorganized ultrastructure. (B) Most Z-discs were diffusely stained, irregular in shape (black arrowheads), or seemingly absent (white arrowheads). Insets: Cross section through myofilament bundles indicated a normal primary organization of thick and thin filaments in hexagonal lattices in flncb-depleted hearts. (C) Sarcomere arrangement in myofibrils (m) was often nonconsecutive, with (D) multiple sarcomeres sometimes adjoined to a mass of Z-disc-like material (z). (E) Small vacuoles (v) were often present between or near the plasma membranes of adjacent cardiomyocytes. These vacuoles could be large, creating a gap between adjacent cells. (F) Autophagic vesicles (a) were observed. Scale bar: 1 μmol/l. Abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Discussion

This report presents 2 rare splicing variants in FLNC cosegregating in 3 families with DCM; both c.7251+1G>A and the c.5669-1delG variants were absent from all queried databases (1,000 Genomes Project, NHLBI GO ESP, and ExAC). Interestingly, c.7251+1G>A was detected in 2 Italian families that reside in the same region of Italy. This finding suggests a founder-effect that is not unprecedented in FLNC, as a W2710X FLNC variant was reported in 31 individuals of 4 German families with myofibrillar myopathy (MFM; MIM#609524) (36). Furthermore, FLNC variants have reduced penetrance, as described in familial DCM (4). FLNC variant carriers in our study showed an arrhythmogenic trait, with high incidence of sudden cardiac death. Remarkably, arrhythmias were also reported in restrictive cardiomyopathy (atrial fibrillation, conduction disease) and HCM (sudden cardiac death) associated with FLNC variants 13, 14.

FLNC is primarily expressed in striated muscle, where it clearly plays an important role on the basis of its association with myofibrillar myopathies 10, 12, 36, 37. The FLNC protein is relatively specific to skeletal and cardiac muscle, where it is has been shown to be an actin-cross-linking protein and interacts with the dystrophin-associated-glycoprotein complex, integrin, and Z-disc proteins (FATZ-1, myotilin, myopodin), suggesting its role is to provide mechanical stability within the sarcomere 37, 38.

Variants in FLNC cause MFM (MIM#609524), a disease characterized by disintegration of skeletal muscle fibers, first reported in a German family with a nonsense mutation in FLNC with autosomal dominant inheritance and presentation of limb girdle myopathy (12). Variants in FLNC leading to skeletal myopathies include protein-coding missense mutations, insertion/deletion mutations, frameshift deletions, and nonsense mutations. These mutations are distributed across the protein, including the NH3-terminal actin-binding domain (8), the central immunoglobulin-like domains 9, 10, 11, 39, and the COOH-terminal dimerization domain (12).

As has been demonstrated with other filamins (FLNA and FLNB), the phenotype displayed in affected FLNC patients varies with the position of the mutation and the functional domain affected 8, 37. The FLNC gene mutation c.5160delCfs (p.Phe1720LeufsX63) (9) has been shown to lead to nonsense-mediated decay, resulting in reduced messenger RNA levels with undetectable expression of the mutant allele and reduced protein levels as shown by staining in muscle biopsies (37). Our study demonstrated an abnormal splice product and reduced cardiac FLNC protein levels related to FLNC splicing variants. Loss-of-function (LoF) variants are uncommon in FLNC, as evidenced by data from ExAC. In over 60,000 sequenced individuals, the frequency of FLNC LoF variants is lower than expected, leading to a high probability of LoF intolerance for FLNC (40). Collectively, these data support the notion that the variants reported here affect splicing, reduce cardiac FLNC protein levels, and are likely poorly tolerated from an evolutionary perspective.

A subset of mutated FLNC myopathy patients have reported “cardiac phenotypes,” with 1 study reporting one-third of patients having overt cardiac abnormalities, including conduction blocks, tachycardia, diastolic dysfunction, and left ventricular hypertrophy (36). Recently, cases of familial HCM in the absence of muscle involvement have been reported. Valdes-Mas et al. (14) demonstrated that patients with the cardiac-restricted phenotype of HCM had FLNC mutations (8 different nonsense and missense variants in 9 families) mapping to the actin-binding and immunoglobulin-like domains, with a penetrance of >87%. As with our patients, none of the patients with HCM exhibited MFM. More recently, missense mutations (FLNC c.4871 C>T and c.6478 A>T) were found among restrictive cardiomyopathy patients who also had no evidence of skeletal muscle abnormalities (13). This provides evidence that FLNC missense mutations can also lead to disease through a variety of mechanisms. The published reports show increased recognition of FLNC importance in cardiomyopathy.

Our finding of a cardiac-restricted phenotype of DCM in 2 Italian families carrying the identical FLNC mutation in addition to a U.S. family with a different FLNC mutation further amplifies the complexity of FLNC-associated pathology and raises the question of the source of the observed clinical variability. Certainly part of this variability resides in the biochemical functions of different parts of the FLNC protein, as well as in the nature of the mutation (nonsense, missense, splicing). In the case of our patients no skeletal muscle tissue was available for analysis. However, the cardiac tissue we examined showed decreased levels of FLNC protein expression for the N- and C-terminal ends. This apparent reduction in FLNC protein from an explanted human heart harboring the c.5669-1delG splicing variant supports a haploinsufficiency model.

Previous studies may not have appreciated FLNC mutations in cardiomyopathy populations in the absence of other muscle involvement due to its absence from current clinical DCM and HCM genetic screening panels. We expect that as WES is expanded in the clinic, more “atypical” presentations of mutations in FLNC (and other genes) will be identified. Among our 3 families, in which 2 families shared 1 mutation, the FLNC variant did not cause skeletal muscle phenotype, but was associated with a high risk of arrhythmia and a risk of sudden death. The supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias occurred in spite of nonsevere left ventricular dysfunction and dilation. Our zebrafish data support this model, and functional reduction in expressed flncb caused looping and chamber morphogenesis abnormalities in the heart tube, reduced systolic function, altered patterns of embryonic blood flow, and the development of a cardiac edema phenotype. Our data show that knockdown of flncb causes a severe and irreversible cardiac phenotype that leads to increased death once embryos become dependent on their circulatory system for survival. Although it has not been absolutely proven that embryos died at 7 dpf because of cardiac insufficiency, there is a strong presumption given the demonstrated cardiac phenotype and the fact that a large majority of zebrafish with mutations in essential cardiac genes all die about 7 dpf. Before day 7, mutant embryos remain alive even when the heart is completely noncontractile, because they obtain oxygen via diffusion through their skin 41, 42.

These findings suggest that knockdown of flncb in zebrafish induces poor systolic function that is required for normal cardiac morphology and contractile behavior. There is a difference in the severity of the phenotypes, which is not unexpected because the human subjects are heterozygous and experiencing late-onset phenotype, whereas our zebrafish model depicts the consequences for embryonic, full, or strong LoF of FLNC.

To better evaluate contractile function in zebrafish embryos, we examined the ultrastructure of cardiomyocytes at 72 hpf by TEM. In contrast to the well-arranged sarcomere structures of the wild-type control hearts, flncb+p53 MO hearts showed sarcomere organization defects. In particular, most Z-discs were irregular or seemingly missing in flncb+p53 MO embryos. The Z-disc is a complex multiprotein structure that links the sarcomere, costamere, and sarcolemma within heart and skeletal muscle. Z-discs provide mechanical integrity to the sarcomere that allows it to withstand large forces associated with contraction. Moreover, the Z-disc can serve as an integrative site involved both in receiving and transmitting signals associated with biomechanical and biochemical pathways 43, 44, 45. Z-discs are required for myofibril stability 43, 46 and the presence of compromised Z-discs is often accompanied by disrupted sarcomeres (43). The cardiac ultrastructural defects in flncb+p53 MO hearts likely underlie the weaker contractility of these hearts, which would in turn impact the pattern of blood flow. The structural abnormalities in Z-discs of flncb+p53 MO hearts is particularly intriguing because mutations in several Z-disc components are known to cause DCM 47, 48, 49, 50.

The ultrastructural phenotypes observed in zebrafish flncb+p53 MO cardiomyocytes share certain commonalities with skeletal muscle phenotypes observed in knock-in mice heterozygous for a patient mimicking a FLNC mutation (51), including the dissolution of Z-discs and presence of possible autophagic vesicles. However, differences are also apparent. Z-disc streaming, the degeneration of intermittent myofibrils, and mitochondrial enlargement were not observed in zebrafish hearts at 72 hpf. However, further study is required to determine whether flncb-depletion phenotypes in cardiac versus skeletal muscle are fundamentally different. Alternatively, zebrafish hearts at later stages of development, or under stressed conditions, might show phenotypes more akin to those of the skeletal muscle of FLNC heterozygous mice. Many human MFM pathologies, including filaminopathies, exhibit cytoplasmic protein aggregates in skeletal muscle, and recent evidence indicates their presence as well in adult cardiac tissue of patients heterozygous for FLNC mutations 13, 14. Whereas our studies did not identify such aggregates in the 72 hpf zebrafish embryonic heart, a broader study should investigate aggregate-specific markers and additional ages or conditions to clarify whether and when protein aggregates appear in this model.

A recent report of Chevessier et al. (51), described Z-line lesions in a FLNC p.W2710X heterozygous mouse model, preceding the classical MFM protein aggregates that characterize the FLNC disease. Interestingly, these lesions were greatly increased in number following acute physical exercise in mice. The investigators suggested that the mutant filamin influences the mechanical stability of myofibrillar Z-discs. In this regard, in our patients there was no history of intense exercise in any of the affected individuals in the 3 pedigrees to potentially explain differences in age of onset or severity of phenotypes, and there was no association of exercise with major ventricular arrhythmic events and sudden cardiac death.

Study limitations

A limitation of the zebrafish model is that detailed phenotypic analysis in MO knockdown studies is most reliable for only the first few days of development. Although we have not examined the functional activity of proteins resulting from mis-spliced transcripts of zebrafish flncb messenger RNA, these proteins are likely to be poorly functional because they would lack major C-terminal portions of the protein, including several immunoglobulin repeat regions, both hinge regions, and the actin-binding regions (52). The current MO studies indicate an essential requirement for FLNC in the developing heart and demonstrate that its loss causes cardiac dysgenesis via effects on cardiac morphology, ultrastructure, and biomechanical dynamics (contractility and blood flow). Whereas a splice blocking MO that mimics the human allele could be generated, a careful analysis would need to be done to confirm whether the resulting zebrafish phenotypes represent strong or only partial LoF. Whereas this more subtle characterization of allelic behavior could be very interesting, a Cas9 RNA-guided CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat) genome editing approach would be strongly preferred to avoid the limitations of MO, such as dose dependency and off-target effects.

In this study, the flncb gene was selected as the initial candidate to test the hypothesis that FLNC protein is critical for cardiac development, on the basis of the 82% amino acid identity between zebrafish Flncb and human FLNC. The zebrafish genome also contains a flnca ortholog that is reported to have minimal cardiac expression (25). We have preliminary data indicating that flnca is indeed expressed in 48 hpf zebrafish hearts, and further studies will therefore be needed to generate flnca mutants and determine whether doubly mutant embryos have a stronger cardiac defect than do flncb-depleted embryos.

Cardiac tissue was unavailable from 2 of our families (TSFDC029 and TSFDC031), limiting our ability to infer mechanisms beyond the data from the affected heart studied from family DNFDC057. We predict that our reported FLNC variants alter RNA splicing, likely leading to reduced protein expression and DCM via a haploinsufficiency model. The reduced FLNC protein we report from an affected explanted heart is consistent with this model, but additional data are needed before concluding that haploinsufficiency is the principal mechanism of DCM in these families.

Conclusions

Using WES in families with previously unknown causes of DCM, we have described 2 novel splice site mutations in the FLNC gene, which cosegregated with a severe cardiac phenotype characterized by a high rate of arrhythmia and sudden death. The DCM phenotype was cardiac-restricted with no skeletal myopathy. The variants detected lead to abnormal splicing and may mediate pathogenicity via haploinsufficiency, as supported by our functional zebrafish data and Western blot analysis, suggesting that approaches to augment endogenous FLNC protein could represent a treatment strategy in these cases. Our data, together with 2 DCM population screenings 53, 54, the study of other cardiomyopathies (HCM and restrictive) 13, 14, and previous data on MFM 4, 10, 12, 36, 37, suggest that FLNC rare variants can cause a spectrum of cardiac and skeletal muscle phenotypes. Finally, studies in vivo (mice, zebrafish, and medaka fish) 25, 51, 55 further support our findings that suggest FLNC mutations can lead to sarcomeric structural changes and ultimately cause cardiac dysfunction.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: The search for genetic defects of approximately 50% of DCM cases without a known cause continues. In this study, we report that FLNC gene truncations cause DCM in 3 families and provide in vitro and in vivo supportive evidence for haploinsufficiency as the pathogenic mechanism. Our data show that FLNC variants are capable of causing a DCM phenotype without any overt skeletal muscle involvement. These data are to be interpreted in the context of previously reported FLNC myopathies that appear to be restricted largely to skeletal muscle. Concluding that FLNC variants are further capable of leading to DCM adds to the growing interest and understanding of FLNC mutations in human muscle diseases and sets the stage for further studies to determine whether up-regulation or other manipulations of the FLNC protein could be viable treatment strategies.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Although the identification of rare variants in FLNC represents an important initial step, this finding needs to be supported by further studies addressing the mechanisms by which FLNC mutations may lead to cardiomyocyte dysfunction and human cardiac disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the family members for their participation in these studies and David Bark and Alex Bulk for assistance with video recordings. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Giulia Barbati, PhD, Biostatistician of the Department of Cardiology University of Trieste, for her expert revision of the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants UL1 RR025780, UL1 TR001082, R01 HL69071, R01 116906 to Dr. Mestroni, and Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute grants K23 JL067915 and R01HL109209 to Dr. Taylor. The human cardiac tissue bank was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant UL1 TR001082. Funding was also received from CRTrieste Foundation and GENERALI Foundation to Dr. Sinagra. This work was supported in part by a Trans-Atlantic Network of Excellence grant from the Leducq Foundation (14-CVD 03). The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Appendix

References

- 1.Jefferies J.L., Towbin J.A. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2010;375:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron M.S., Olivotto I., Zenovich A.G. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2006;114:2232–2239. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershberger R.E., Cowan J., Morales A., Siegfried J.D. Progress with genetic cardiomyopathies: screening, counseling, and testing in dilated, hypertrophic, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:253–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.817346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershberger R.E., Hedges D.J., Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parks S.B., Kushner J.D., Nauman D. Lamin A/C mutation analysis in a cohort of 324 unrelated patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2008;156:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roncarati R., Viviani Anselmi C., Krawitz P. Doubly heterozygous LMNA and TTN mutations revealed by exome sequencing in a severe form of dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:1105–1111. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kley R.A., Serdaroglu-Oflazer P., Leber Y. Pathophysiology of protein aggregation and extended phenotyping in filaminopathy. Brain. 2012;135:2642–2660. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duff R.M., Tay V., Hackman P. Mutations in the N-terminal actin-binding domain of filamin C cause a distal myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guergueltcheva V., Peeters K., Baets J. Distal myopathy with upper limb predominance caused by filamin C haploinsufficiency. Neurology. 2011;77:2105–2114. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823dc51e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luan X., Hong D., Zhang W., Wang Z., Yuan Y. A novel heterozygous deletion-insertion mutation (2695-2712 del/GTTTGT ins) in exon 18 of the filamin C gene causes filaminopathy in a large Chinese family. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tasca G., Odgerel Z., Monforte M. Novel FLNC mutation in a patient with myofibrillar myopathy in combination with late-onset cerebellar ataxia. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:275–282. doi: 10.1002/mus.23349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vorgerd M., van der Ven P.F., Bruchertseifer V. A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin c causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:297–304. doi: 10.1086/431959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodehl A., Ferrier R.A., Hamilton S.J. Mutations in FLNC are associated with familial restrictive cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:269–279. doi: 10.1002/humu.22942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valdes-Mas R., Gutierrez-Fernandez A., Gomez J. Mutations in filamin C cause a new form of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5326. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestroni L., Maisch B., McKenna W.J., for the Collaborative Research Group of the European Human and Capital Mobility Project on Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy Guidelines for the study of familial dilated cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:93–102. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry W.L., Gardin J.M., Ware J.H. Echocardiographic measurements in normal subjects from infancy to old age. Circulation. 1980;62:1054–1061. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.5.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell N., Sinagra G., Jones K.L. Whole exome sequencing identifies a troponin T mutation hot spot in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu T.D., Nacu S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:873–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abecasis G.R., Auton A., Brooks L.D., for the 1,000 Genomes Project Consortium An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA. Available at: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/. Accessed November 2014.

- 21.Endeavor. Endeavour: A Web Resource for Gen Prioritization in Multiple Species. Available at: http://homes.esat.kuleuven.be/∼bioiuser/endeavour/tool/endeavourweb.php. Accessed June 2014.

- 22.Aerts S., Lambrechts D., Maity S. Gene prioritization through genomic data fusion. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:537–544. doi: 10.1038/nbt1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerfield M. 2nd edition. University of Oregon Press; Eugene, OR: 1993. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimmel C.B., Ballard W.W., Kimmel S.R., Ullmann B., Schilling T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruparelia A.A., Zhao M., Currie P.D., Bryson-Richardson R.J. Characterization and investigation of zebrafish models of filamin-related myofibrillar myopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4073–4083. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robu M.E., Larson J.D., Nasevicius A. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gene Tools. Available at: www.gene-tools.com. Accessed February 2014.

- 28.Karlsson J., von Hofsten J., Olsson P.E. Generating transparent zebrafish: a refined method to improve detection of gene expression during embryonic development. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2001;3:522–527. doi: 10.1007/s1012601-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowland T.J., Miller L.M., Blaschke A.J. Roes of integrins in human induced pluripotent stem cell growth on Matrigel and vitronectin. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1231–1240. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns C.G., Milan D.J., Grande E.J., Rottbauer W., MacRae C.A., Fishman M.C. High-throughput assay for small molecules that modulate zebrafish embryonic heart rate. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:263–264. doi: 10.1038/nchembio732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson B.M., Garrity D.M., Dasi L.P. Quantifying function in the early embryonic heart. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135:041006. doi: 10.1115/1.4023701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson B., Garrity D., Dasi L. The transitional cardiac pumping mechanics in the embryonic heart. Cardiovasc Eng Tech. 2013;4:246–255. doi: 10.1007/s13239-013-0120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebert A.M., Hume G.L., Warren K.S. Calcium extrusion is critical for cardiac morphogenesis and rhythm in embryonic zebrafish hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17705–17710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502683102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Exome Aggregation Consortium. ExAC Browser. Available at: http://exac.broadinstitute.org. Accessed February 2016.

- 35.Bill B.R., Petzold A.M., Clark K.J., Schimmenti L.A., Ekker S.C. A primer for morpholino use in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:69–77. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kley R.A., Hellenbroich Y., van der Ven P.F. Clinical and morphological phenotype of the filamin myopathy: a study of 31 German patients. Brain. 2007;130:3250–3264. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furst D.O., Goldfarb L.G., Kley R.A. Filamin C-related myopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson T.G., Chan Y.M., Hack A.A. Filamin 2 (FLN2): a muscle-specific sarcoglycan interacting protein. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:115–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shatunov A., Olive M., Odgerel Z. In-frame deletion in the seventh immunoglobulin-like repeat of filamin C in a family with myofibrillar myopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:656–663. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Exome Aggregation Consortium, Lek M, Karczewski KJ, et al. Analysis of Protein-Coding Genetic Variation in 60,706 humans. BioRxiv. Available at: http://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2015/10/30/030338. Accessed March 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Pelster B., Burggren W.W. Disruption of hemoglobin oxygen transport does not impact oxygen-dependent physiological processes in developing embryos of zebra fish (Danio rerio) Circ Res. 1996;79:358–362. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwerte T. Cardio-respiratory control during early development in the model animal zebrafish. Acta Histochem. 2009;111:230–243. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassel D., Dahme T., Erdmann J. Nexilin mutations destabilize cardiac Z-disks and lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/nm.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshijima M. Mechanical stress-strain sensors embedded in cardiac cytoskeleton: Z disk, titin, and associated structures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1313–H1325. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00816.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pyle W.G., Solaro R.J. At the crossroads of myocardial signaling: the role of Z-discs in intracellular signaling and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;94:296–305. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000116143.74830.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volkers M., Dolarabadi N., Gude N., Most P., Sussman M.A., Hassel D. Orai1 deficiency leads to heart failure and skeletal myopathy in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:287–294. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knoll R., Buyandelger B., Lab M. The sarcomeric Z-disc and Z-discopathies. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:569628. doi: 10.1155/2011/569628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morita H., Seidman J., Seidman C.E. Genetic causes of human heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:518–526. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morita H., Nagai R., Seidman J.G., Seidman C.E. Sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophy and heart failure. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grunig E., Tasman J.A., Kucherer H., Franz W., Kubler W., Katus H.A. Frequency and phenotypes of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:186–194. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chevessier F., Schuld J., Orfanos Z. Myofibrillar instability exacerbated by acute exercise in filaminopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:7207–7220. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Flier A., Sonnenberg A. Structural and functional aspects of filamins. Biochimica Biophys Acta. 2001;1538:99–117. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golbus J.R., Puckelwartz M.J., Dellefave-Castillo L. Targeted analysis of whole genome sequence data to diagnose genetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:751–759. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deo R.C., Musso G., Tasan M. Prioritizing causal disease genes using unbiased genomic features. Genome Biol. 2014;15:534. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0534-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujita M., Mitsuhashi H., Isogai S. Filamin C plays an essential role in the maintenance of the structural integrity of cardiac and skeletal muscles, revealed by the medaka mutant zacro. Dev Biol. 2012;361:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.