Abstract

We describe fieldwork in which we studied hospital ICU physicians and their strategies and documentation aids for composing patient progress notes. We then present a clinical documentation prototype, activeNotes, that supports the creation of these notes, using techniques designed based on our fieldwork. ActiveNotes integrates automated, context-sensitive patient data retrieval, and user control of automated data updates and alerts via tagging, into the documentation process. We performed a qualitative study of activeNotes with 15 physicians at the hospital to explore the utility of our information retrieval and tagging techniques. The physicians indicated their desire to use tags for a number of purposes, some of them extensions to what we intended, and others new to us and unexplored in other systems of which we are aware. We discuss the physicians’ responses to our prototype and distill several of their proposed uses of tags: to assist in note content management, communication with other clinicians, and care delivery.

Keywords: Medical note creation, tags, clinical notes, clinical documentation, medical user interfaces

ACM Classification Keywords: H5.2 [Information Interfaces]: User Interfaces, Input; I.3.6 [Methodology and techniques]: Interaction Techniques

INTRODUCTION

A patient progress note is a clinical document, written by a hospital physician, describing a patient’s status and the physician’s assessments and care plan for the patient. An attending physician, who has primary responsibility for the patient’s care, composes a daily note for each of their patients. These notes are referred to by other clinicians as care is transferred or shared, and are included in the official medical record for legal and billing purposes.

Creating a progress note requires a physician to gather, review, and comment on previous and current patient data such as lab results, information from medical rounds, medications, procedures, and tests to determine patient health, as well as select relevant information to put into the current note. Current Electronic Medical Record (EMR) systems [33] include facilities for creating and managing progress notes; however, the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) physicians that we studied do not use the documentation features of these systems, for reasons we mention below. They gather patient data through oral briefings by residents, fellows, nurses and data queries on EMR systems, but then use other tools to note patient progress. They use generic document processing systems, such as Microsoft Word, to insert relevant patient data into a progress note, and use at least one additional documentation aid (paper, self-developed software, or self-designed macros), to assist them in tracking and noting progress.

To understand more about how these physicians compose and use progress notes, and how EMR system design can evolve to accommodate their process, we engaged them in a multi-phase design exploration. First, we conducted fieldwork in two ICUs at New York Presbyterian Hospital (NYPH). Our fieldwork revealed that the clinical information retrieval (IR) capabilities of the EMR systems in use allow access to comprehensive clinical information, but do not adequately allow physicians to automate and customize data retrieval and note management preferences. The systems also do not adequately support task-switching between information searches and free-text editing. Thus, in our design, we focused primarily on techniques to support input and management of electronic progress note content.

Based on our fieldwork, we developed a study prototype, activeNotes, to use as a tool to gain insight into the note creation process. ActiveNotes introduces activeTags to support user control of updates to patient information inserted into a note. We also explored the specification of user-customized alerts associated with these updates.

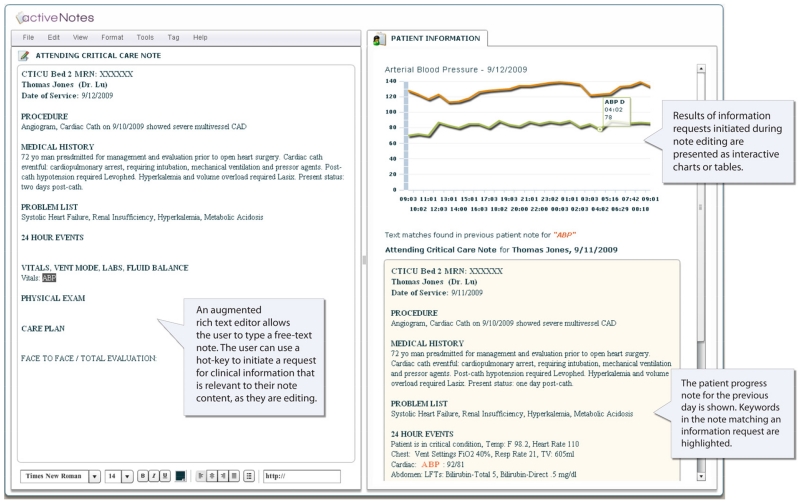

ActiveNotes is an integrated environment that offers physicians two side-by-side views (Figure 1): an editable note view and a patient information view in which the system displays results from data queries. As a note is edited, activeNotes dynamically interprets new content created by the physician in the context of the existing note to detect potential information requests. If requested via a hot-key, the system automatically formulates queries for retrieving information from multiple data sources. The physician can review and insert the retrieved data in real-time, as well as associate with note content an activeTag that will control subsequent updates to that data. Each activeTag links the tagged content with the automatically-generated queries and data actions for retrieval, updates, and alerts. The physician can configure the actions of an activeTag to obtain the updated values at specified times, and have these updates automatically reflected in the note, as well as evaluated against user-specified alert mechanisms.

Figure 1. activeNotes screen.

In the following sections, we first describe related work and contrast it with our approach. We then present insights about physicians’ workflows and current processes for note creation gained from observations, semi-structured interviews, and a survey conducted in two NYPH ICUs. Next, we describe the activeNotes prototype and how it incorporates physician customization of patient information retrieval into the note creation process using interaction artifacts we call activeTags, to manage progress note content. We then present findings and feedback from a qualitative study of the prototype conducted at NYPH with 15 physicians. We describe how physicians applied activeTags and suggested desired uses of tags when used in conjunction with IR: to manage note content, specify IR preferences, communicate with other clinicians, and organize aspects of patient care. We conclude with a discussion of future work.

The observations, interviews, prototype, and feedback sessions we describe are components in a single design exploration. Our primary contribution is the use of these study components to understand the roles of tagging and IR in progress note documentation in two ICUs.

RELATED WORK

We planned our fieldwork based on previous approaches to studying clinician interactions with information artifacts in hospitals [25,32,40]. Literature on modeling workflows and information processes in clinical settings [3,14,20,23] helped us understand how progress note creation and use fits into the complex workflow of the physicians we studied, and where the best opportunities to design interventions lie. Studies of personal note-taking [34] were also helpful in understanding physicians’ use of short, informal personal notes.

The design of activeNotes is motivated by previous work on ICU practice [20], which explores the importance of patient progress notes and the need for computer-assisted support for their creation. Our work is also informed by studies of research prototypes and systems [13,15,37], and commercially-available systems (e.g., [7,21,35]), all of which currently use form- or template-based user interfaces for note creation, configurable at the administration level rather than the user level. Users of these systems cannot view data in the context of the note they are creating without switching views, unless they use a form-based UI, and cannot automate IR tasks. One commercial system is an exception [26], and supports free-text entry and user-defined templates, but does not allow physicians to customize updates to note content, and forces entry of certain note content in the process of free-text note editing. One research prototype [13] for note creation assists physicians in automating IR for managing note content, but does not retrieve lab values and vitals, or allow the user to review several related data items before selecting data for insertion.

Research focusing on specific considerations for supporting patient progress note input (e.g., [30,38]) motivates the need for computer-assisted support for patient information retrieval, integrated into the note creation process, as well as interaction techniques to support updates to notes.

Much work in medical informatics and applied computing has focused on designing systems to extend clinical information availability for mobile contexts (e.g., [2,22]) and for rich content types [6,18]. Recent HCI work has also focused on rich presentation and interaction techniques for viewing and browsing patient data (e.g., [12,24,36]) and novel interactive visualization techniques have been designed to assist ICU physicians in viewing multidimensional clinical data [4]. However, there is little research on how to design tools that enable physicians to flexibly specify management rules and annotations for information updates and progress note content management.

A related application that supports note-taking and sense-making of medical information is Entity Workspace [5]. It allows users to discover high-level information from structured content (e.g., question answering) and to search, read, and create notes in a single environment. It provides automatic highlighting of terms, techniques for importing text from documents into a note, and support for annotating and organizing information in a note. While we also create an integrated environment for searching documents and creating content, we focus primarily on supporting specific queries to retrieve relevant information from dynamic data sources and previous patient notes.

Our design prototype, activeNotes, offers activeTags for updating data and alerts. The term “tag” is often applied to annotations attached by a user to an item [1,9,29]. While we are inspired by and support these types of tags in our prototype, we further extend the idea to dynamic data entries. ActiveTags for these entries serve as identifiers of the data and as placeholders [17, 29] that reflect the ultimate values of the data, and are associated with a set of rules to control how the data entries are reflected in a document. Extending a number of ideas explored in the hypertext literature [10,11], we provide users with mechanisms to manage how dynamic source content is reflected in the new document. However, activeTags go several steps further: they contain source content that is determined by interpreting a user’s information request automatically, based on an analysis of note content, as well as queries for searching for patient data from multiple sources, also determined automatically.

Previous tag facilities include Smart Tags (in Microsoft Office), which can automatically recognize common entity types such as a person’s name or address, and supports type-specific actions to perform common tasks (e.g., add a name to an Outlook address book) [17]. A Smart Tag can also be preconfigured to link to content (e.g., a legal clause) in a content management system, such that changes to text in document content will be dynamically populated via the linked content tag. ActiveTags differ from Smart Tags in three ways. First, upon creation of an activeTag, our system interprets its associated content in the context of other text in the document to formulate queries on source content. For example, if the query needs identifying patient data, it will obtain it automatically from other sections of the note. Second, activeTags allows users to determine what to tag and offers control of update and alert mechanisms for managing the tagged content. Third, rather than linking to a specific single source, activeTags are associated with one or more queries, such that the content linked to by an activeTag is not a document, single entry in a database, or action, but a set of queries that may be used to retrieve results according to user-specified, data-aware, rules.

Our use of activeTags to assist note creation is also inspired by the work of Hsieh et al. [16]. They introduce tags in instant messaging (IM) that alter the behavior of the tagged items (messages) to facilitate near-synchronous communication in IM clients. Senders can tag their IM messages to trigger different types of support on the receiver’s side for different types of tasks (e.g., tasks that do not require immediate attention, or tasks that have deadlines).

NOTE CREATION IN THE ICU

We observed the workflow, environment and note creation strategies of six physicians (two attending physicians and four residents) over an elapsed time period of six months in the NYPH Cardiothoracic ICU (CTICU). We conducted a written survey of eight attending physicians in the CTICU and NYPH Surgical ICU (SICU), including the two attending physicians observed earlier (for a total of 12 observed and/or surveyed). We also conducted semi-structured interviews with all 12 physicians at NYPH.

The note creation process includes the formulation of assessments and care plans for the patient. Physicians gather factual information from multiple sources such as the EMR systems, the patient database, printed lab reports, prior patient notes, and oral presentations or written records of residents and fellows. We found that much of the note creation process in the ICU occurred in the context of collaborative group discussion and question-answering, often during a process called ‘medical rounds.’ As previous work on information seeking in ICUs suggests [27,28], during these collaborative discussions, physicians asked several types of questions to determine a patient’s status and plan their care. Some answers can be found in clinical data sources, but many include experiential or organizational information, gained through discussion with other clinicians and their own observations. We found that physicians logged these comments and observations as they arose in the context of group conversation and patient care, at the patient’s bedside, and preferred to create their own note structure and type freely during this process. While they also document clinical patient data found in the EMR system, they do not want to be hindered by structure or additional task-switching during rounds, so they perform data lookups separately, noting placeholders for information during the composition process. Gaps in resident reports, as well as the lack of data availability on the devices used during rounds, account for most of these placeholders. Physicians estimated that, typically, 25-50% of the information they requested from residents during rounds is not known or noted by a resident, even if it is in the database, requiring that this information be looked up after rounds and documented.

We further studied clinical information needs during note creation, and found that they are dynamic and context-sensitive, as they depend on patient status and content that has already been entered in the patient note. For example, below the heading “Abdomen” in a note section entitled “24 Hour Events”, physicians may need lab results for the past 24 hours related to the patient’s liver function. In contrast, below the same heading “Abdomen” in the “Physical Exam” section of a different note, physicians may need information about whether bowel sounds were present for the patient during the most recent physical exam.

Attending Physician Survey

We conducted a survey to learn more about the current note creation process, including individual mechanical processes for composing notes, challenges involved in creating and updating note content related to the information systems and applications currently in use, and the frequency with which notes are updated and referred to throughout the day. We asked physicians to answer questions about their experiences composing the Attending Critical Care Note (the progress note that is submitted to the medical record).

Among the eight attending physicians surveyed, four have worked in an ICU for less than three years, one for five years, and three for more than 20 years. They estimated that their typical day in an ICU lasts around 9–12 hours, during which they reported spending 2.5–8 (mean = 5) hours on medical rounds for patient care. Each physician estimates writing 10–18 (mean = 16) notes per day. Six create 80–90% of note content during medical rounds, while two create their notes after rounds, relying on their memory.

Five of the six attending physicians who compose patient notes during medical rounds at the patients’ bedsides use a laptop computer and a document processing application such as Microsoft Word. One physician handwrites patient notes during rounds and types them into a computer later. All physicians surveyed consider the task of collecting relevant and correct patient data the greatest challenge in composing an Attending Critical Care Note. They admitted spending considerable time navigating through previous notes to locate relevant patient information, especially notes written by other physicians. Most of this time is spent visually searching through documents to find pieces of information relevant to their current information need.

A patient note is usually not inserted into the patient record immediately after it is created. The physicians estimated that up to eight hours could elapse between the point at which the note is created and the time it is submitted to the record, during which they continue monitoring patient status. Throughout the day, the physicians keep track of patient information, such as lab results, vital signs, and ventilator settings, to analyze a trend of measurements, detect abnormalities, and adjust assessments and plans for patient care accordingly. While the attending physicians all agree that patient notes should be updated to reflect the above changes, they have different opinions on when the updates should be performed. Two physicians think notes should be updated immediately when new information becomes available; two would like to update notes periodically, and four consider it sufficient to perform updates once before notes are submitted to the patients’ medical records.

When asked how convenient it is to make updates to an Attending Critical Care Note directly using current systems, six of the eight physicians said that it was either somewhat inconvenient or very inconvenient. Follow-up by residents is the primary source of the updated information, updates are typically delivered verbally, and the physicians have to manually edit each note once they obtain these updates.

The surveys also revealed that physicians have rejected rigid template or form-based UIs for creating notes that impose a strict document structure, because the structure often conflicts with their mental model of the patient’s current status. They have also rejected systems that require heavy task switching between IR and text editing. Other key problems related to keeping note content up-to-date and complete were identified:

Physicians often rely on their own memory, or a jotted reminder, to update the note with any missing data that becomes available after the note is created. Such a list varies from patient to patient.

If new data becomes available, updates to the note require that a physician repeat the manual data retrieval and insertion process described earlier.

It is time consuming to locate in the patient note related content pieces that require updating and to replace them one by one with the updated values.

Tools to enable monitoring preferences for specific information and define criteria for physician notification about data availability are limited in the current EMR systems.

Physician-Designed Interventions

Each physician surveyed keeps an informal, shared, note, accessible on the NYPH intranet, to log observations and patient information. This informal note is entered and accessed via a web form, consisting of four large text boxes, without labels, designed by the physician coauthor of this paper. Physicians use this unstructured form as an easy way to communicate information among care team members, separating information to match a care situation, a process that does not always conform to structured headings. They refer to this form as the “cheat sheet” because it allows them to write their thoughts along with patient data that is relevant to patient care throughout the day, in a manner that does not require adherence to a specific structure. Physicians create their own structure for the patient using the free-text areas, and this varies from patient to patient.

Some physicians also frequently print their own note templates to informally log data and aspects related to care delivery on paper, writing on the paper throughout the day. They sort through the information and choose items to insert into the Attending Critical Care Note, from the paper, at the end of their work day. One also programmed a macro in Microsoft Word to help him with auto-completion of his most frequently used terms in a note.

ACTIVENOTES

ActiveNotes is a study prototype that queries data from a composite, anonymized, patient profile created from the hospital database. Our goal in designing this study prototype was to adopt a realistic data schema, with comprehensive patient data for a sample patient to provide as much authenticity as possible on which to base responses, while maintaining the design flexibility required to conduct a formative study. We note that further research is needed to extend our design to comply with relevant standards, requirements for hospital billing, and thorough provisions for patient safety. We implemented activeNotes using a combination of Adobe Flash with Adobe Flex 3 for the UI and Java for the back-end.

Design Process

Following our initial field work, we analyzed findings from our observations, our interviews with physicians, the data types in the EMR systems, and approximately fifty previous printed progress notes. Based on this work, we formulated the following design goals:

Allow free-text note entry with context-sensitive support for IR via information requests, initiated in the editor.

Allow the user to specify a data request for all labs related to a particular organ system or function through high level terms (e.g., all lab work related to heart function with a request for “cardiac” or “chest”).

Allow data displayed in result sets to be inserted in the note with minimal keystrokes or mouse clicks.

Provide annotations of automatically inserted data items and data review capabilities for verifying note content before note submission.

Provide customizable support for managing note content, according to user-defined settings. For example, allow users to group note entries under a category of their choosing, and perform subsequent data look-ups for all items in a category.

Provide support for reviewing updates to data included in a note and viewing the history of noted data.

Display the progress note for the patient from the previous day, and highlight items in the previous note that are relevant to an information request to facilitate analysis of changes.

We also iterated through sketches of proposed note editing UIs with two collaborating physicians, who helped us to identify clinical vocabulary requirements, and usage examples for our design prototype.

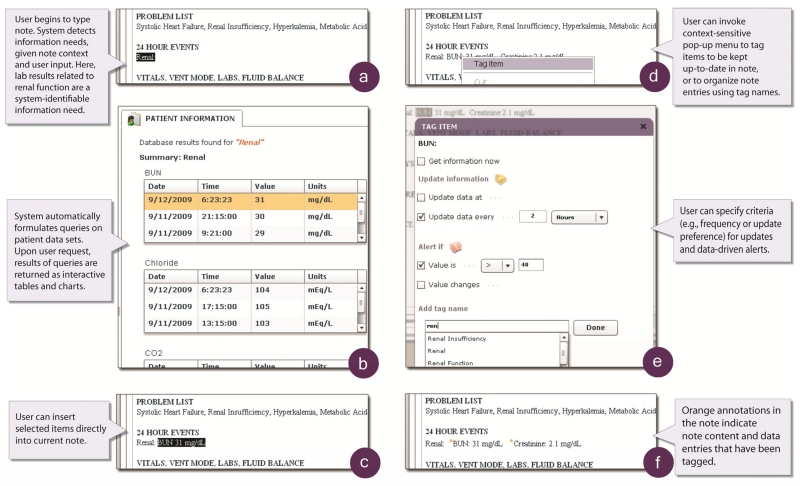

The activeNotes UI includes two main interaction areas: the Note Area on the left, entitled “Attending Critical Care Note” (Figures 1, 2a,c,d,f) and the Results Area on the right entitled “Patient Information” (Figures 1, 2b). The note area is an augmented rich text editor. A user can type her note as she normally would, and at any time during note editing, can signal the system (by pressing Ctrl-Space) to retrieve the needed patient information based on the content inserted into the note thus far.

Figure 2. ActiveNotes user performs a data query and inserts the query result, then tags the query with an activeTag.

Data Retrieval

Data retrieval in activeNotes is supported by the recognition of text in the context of the note entered in the note view (Figure 2a). When requested, the system looks at text that the user has just typed, highlights the last term that it recognizes as an information request, and automatically formulates queries to retrieve information relevant to the request from appropriate data sources. The system adopts an existing natural language input processing algorithm [19, 39] to analyze existing note text to build appropriate queries. For example, a physician wanting to check on lab results related to the patient’s renal function (in this context, how well the kidneys are filtering blood) can type “renal” in the note and press Ctrl-Space to request relevant data (Figure 2a). The system detects the information request and formulates database queries to retrieve the values of relevant data items such as the patient’s Blood Urea Nitrogen, or BUN level (how much broken-down protein still exists in the kidneys to indicate how well they are filtering this protein) and Creatinine level (small molecules of creatine waste, also filtered by the kidneys) (Figure 2b). Occurrences of this information in the previous day’s patient note are also highlighted to speed reference to relevant content in that note. A user can click a data point in a chart or in a row of a result table to indicate her wish to have the corresponding result automatically inserted into the current note.

Each information request is interpreted in the context of the existing note so that relevant information (e.g., patient identity, date, time, or organ system under review) can be embedded by activeNotes in the automatically-generated queries. Users can request a single piece of information (e.g., heart rate), or multiple pieces of related information at once (e.g., ventilator settings, or information at the organ system level such as renal). Retrieved information is placed in the patient information view and can be automatically inserted into the note (Figure 2c). In this way, note-driven retrieval allows users to dynamically gather data while entering free-text and without leaving the current UI or losing control over content, format, or structure.

ActiveTags

An activeTag is an annotation that is attached to a content fragment and associated with data actions (retrieval, updates, and alerts) that act upon that content. Users can attach activeTags to data-related note content to indicate their wishes to obtain live updates, or to receive alerts when the automatically updated content meets certain criteria (e.g., exceeds a threshold). Users can also use activeTags to request automated updates for patient data that was not available when initially requested. This way, users can avoid forgetting to revisit a patient note to fill in missing data.

To associate an activeTag with some content in the note, a user can click anywhere within the word to have it selected and highlighted, and right-click to bring up the context-sensitive tag menu (Figure 2d).

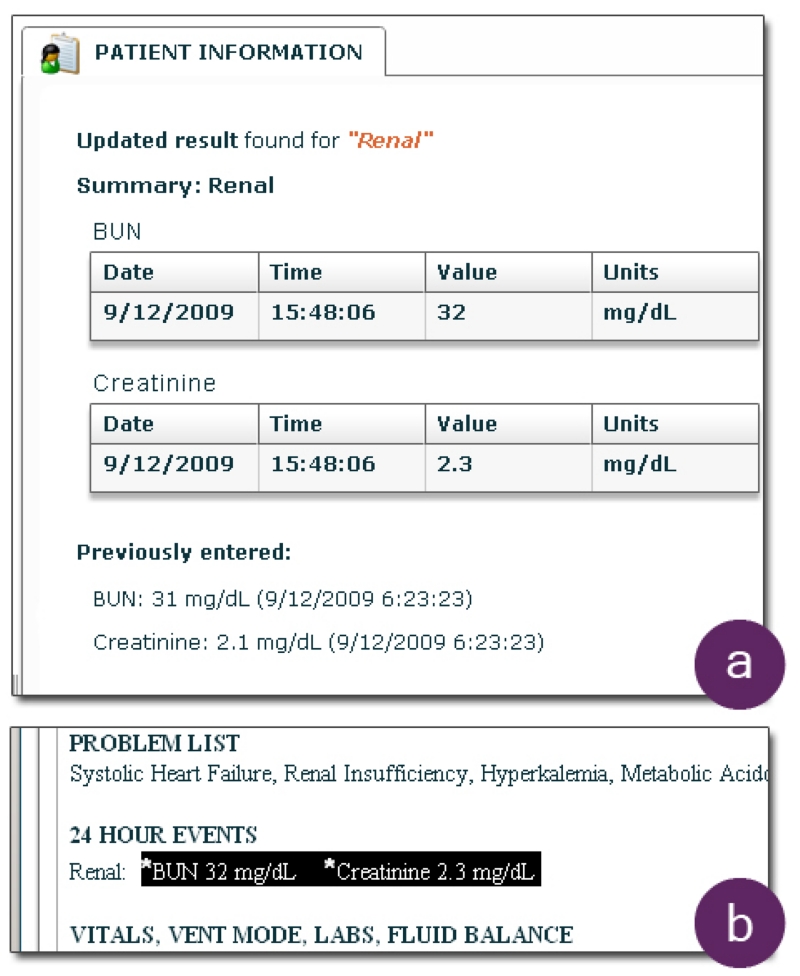

Users can configure an activeTag by choosing among different options for when and how to perform updates. For example, a user can request that an update be run immediately, at a specific time, or on a specified schedule (Figure 2e). Users can specify through preference options whether or not the originally inserted value should be automatically replaced with the updated value (Figure 3a–b).

Figure 3. An update is displayed and reflected in note content.

In addition to update options, users can request that an alert be generated if user-specified criteria are met. Users can choose to receive alerts (by email or SMS message) when the updated value goes above or below a threshold value, and/or when the updated value increases or decreases by a specified amount relative to the original value.

Physicians can also use activeTags to create labels that are meaningful to them, to organize content across patient notes, without setting data retrieval preferences. At any time, a user can choose to view and manage all the activeTags organized by labels, or based on user-specified update or alert options (e.g., times or frequencies of updates, and types of alerts). Users can also use activeTags to track the value of a data item over time.

The numeric data items retrieved from the database are presented in interactive charts or tables whose format is determined by the amount of data retrieved and user-set preferences. The previous patient note is also displayed with the matched keywords highlighted. The user can click on the data she deems relevant to the note, causing it to be inserted into the note automatically at the position where she issued the information request.

In developing our study prototype, we implemented support for note updates using activeTags; however, we did not actually deliver alerts that were specified using the activeTag menu, since we performed the study for a fictional patient.

We presented activeTags to physicians as a tool to assist in managing note content by attaching annotations to note content, and specifying automatic update and alert criteria with patient information retrieval. We designed these based on their use of personal notes to assist them in recalling note updates. However, our motivation in introducing these tags was also to understand how physicians appropriated and desired to use the tagging functionality in the context of editing progress notes.

Automation

An important design choice in creating our prototype included the decision to enable automatical updates to note data. Indeed, values that are populated or updated automatically should be reviewed for accuracy, and consistency of values with written statements on progress should be reviewed. However, the requirement that updates be edited manually is burdensome in both cognition and time, and the current preferred documentation method relies heavily on manual entry due to the flexibility it affords for commenting in free-text, introducing several hazards [38]. As Embi et al. [8] point out, different approaches to reviewing and inserting note content will result in different cognitive behaviors, potential hazards, and impact on workflow. To address this in our design, all tagged values are annotated in the note (Figure 2f) and updated values are also annotated in the note and complemented with a history of the updated value shown in the right-hand pane (Figure 3b). Users can view updates without automatically updating note content.

QUALITATIVE STUDY OF ACTIVENOTES

We conducted a qualitative study with 15 (11 male, 4 female) physicians at NYPH, all between 29–55 years old; 11 are attending physicians, and four are residents with one to four months of experience in an ICU.

Environment

Working within the realities of a hospital ICU posed challenges for the design of our study. Physicians were often on call, and a request for even 30 minutes of their time is a lot. Thus, we planned a training session, task, and survey that could be completed in at most 30 minutes. Since we were at risk of interruptions from cell phones and pagers, we opted for qualitative feedback during and after use of the system.

Method

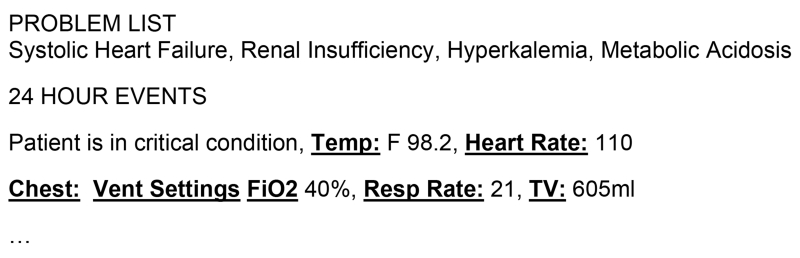

Both the training and study task were performed using a laptop computer we provided with a mouse that could optionally be used instead of the built-in trackpad or track-point. The task involved first reading a scenario setting the background information on our fictional patient, and two Attending Critical Care Notes for this patient from the previous day. Of the two Attending Critical Care Notes provided for training purposes, one resembled a standard note in a patient medical record, with no additional annotations. The other was annotated to include underlined and bolded terms. These annotated terms denoted words the system had recognized and used to retrieve patient data results (Figure 4). After a participant read the patient scenario, the study coordinator introduced activeNotes, comparing and contrasting it with word processing applications familiar to the participant, and described the features with examples.

Figure 4. A fragment of the annotated note used for training.

Training included using three sample terms for which the system formulated queries and provided results. Results were presented in the right hand panel of the application, with highlighted occurrences of the keyword in the previous patient note, and other data query results. Thus, the participant could also use the information request utility to navigate the previous Attending Critical Care Note, as well as view results from the patient database.

In the examples, the study coordinator demonstrated the difference between an information request to the system on a specific item like “BUN” included as one item in a “Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP)” and a higher-level request, such as “BMP”. With the latter, the system returned multiple lab results for the patient, including BUN. The third example was an information request for the less specific term, “Renal”. Results here included tables of data items that would be noted when evaluating the patient’s renal function, such as BUN, Creatinine, CO2, Albumin, and amounts of urine expelled. In all cases, the previous day’s note was displayed with the corresponding terms highlighted. The physicians were shown how to insert data by clicking on the results, and how to tag note content to set automatic updates and create personalized data alerts. Participants then practiced a few data look-ups and note insertions.

After practicing, we asked them to continue completing the progress note for this patient, allowing them to use the system without intervention. Three sections of the note were pre-filled-in to provide some context. Physicians were asked to focus on one of the following empty sections: “24 Hour Events” or “Vitals, Vent Mode, Labs and Medications”. We asked each participant to use a “think-aloud” protocol and comment on their experience obtaining, inserting, and managing data related to their information needs.

Since we had sample data for labs, vital signs, blood gases and ventilator settings, we instructed them to assume that any information they could not look up was unchanged from the previous day (noted in the background information we provided). They were allowed to refer to the annotated note for examples, as well as enter any terms for information they wished to request, even if those terms were not listed as examples on their reference sheet. After they completed a note section, we asked each participant qualitative questions to structure their feedback, including “What is the greatest benefit of the system?”, “What is a major drawback of the system?”, and “In your opinion, would physicians use this? If so, why? If not, why not?”

FEEDBACK AND DISCUSSION

One goal in studying physician use of our prototype was to understand how ICU physicians might manage progress note content given techniques to perform context-sensitive retrieval of patient data during note editing. A second goal was to understand how ICU physicians might use tagging in conjunction with IR. Comments from physicians describing their experiences are outlined below.

Comments on experience using activeNotes for editing

Physicians were uniformly positive in their desire to use activeNotes to compose patient progress notes. Several volunteered that it was an improvement over the current method for retrieving and noting patient information. Spontaneous comments included that from P15, “this is head and shoulders above what we’re using now” and P5, “this is a heck of a lot better than anything else I’ve used.” One physician believed that typing any part of the note is an administrative task and that any system that required typing was unusable, and did not complete the study task.

With regard to favorite features, half the participants explicitly mentioned the ability to tag items for updating and/or alerting as the key feature they would keep. Most others also mentioned the importance of tagging for updates or alerts at other points in the survey. Opinions varied as to whether updates or alerts were the more important form of tagging. In all, using tags to set up either updates, alerts, or both were considered important by 13 of the 15 participants. Of the two who did not consider tags to be important, one (P9) was the physician who would not complete the study task. The other (P6) was not interested in using activeTags for their proposed use, but mentioned that he would like to place orders for medications and tests, and set up alerts for the purpose of being notified when a “tagged task” was completed (e.g., after the results of a test he ordered are in the database).

When asked to describe the greatest benefit of our system, physicians offered phrases like “[it is] easier to stay organized about following up on things” and “I like being able to see yesterday’s note like that”. Benefits frequently named included those related to time savings, efficiency, ease of inserting items into the note, and ease of updating the note. Physicians felt the facility with which they could include “fresh” information might result in higher quality notes. For example, P3 said, “What I like about this is that every note that is composed is ‘fresh’. I can bring in today’s information easily without having to retype so many things, so I don’t worry about copying something and not updating it, but I can also write comments and put things exactly where I want them in the note... When we do include one from the results, it has a value and a unit, and this is good because, we’re told not to write things like, ‘insulin 10 u’. I think this is a good mix. A system like this makes more sense than the alternatives now.”

Major drawbacks cited included a concern that it might take long to learn what keywords the system recognized. While we had prepared a study vocabulary based on an analysis of previous notes, we found that a few physicians used CTRL-Space after information headings that made sense, but for which we did not have entries in our dictionary.

Use of activeTags

During the study, physicians applied activeTags and suggested desired uses of these tags for note editing. Below we outline these uses and offer several illustrative comments.

Grouping items for data retrieval

We found that several physicians wanted to tag a number of patient data items using a single heading, then specify update and alert criteria for all data items associated with the tag. For example, P13 said, “I want to tag a few different things that I look at, like the blood cell count and the platelet count, with the same tag. Then set up updates for that tag name to see both things get updated together.”

Sharing information with other members of the care team

Physicians mentioned their desire to share tagged data with other care team members, through alerts to those team members, and annotations to the “next person who has to read this”. P5 said, “Alerts would be really great if I could not only set one up for myself, but for the resident, as a way to remind them to follow up on this thing.”

Organizing note content

Physicians commented that they would use tags to “rank items in terms of importance” and “separate informal notes” from formal note content during note editing of the Attending Critical Care Note. P4 commented, “Note completion is not a learning task about the patient’s condition— it’s figuring out what needs to be said about this patient based on what is going on with him or her, and this would help me to better identify that.”

Assisting in recalling items related to care delivery

Many physicians commented that they would like to use the tags to note tasks that are related to care delivery. P15 said, “Take cultures, for example. I might only tag culture results for an alert. But this is something I would definitely use. Cultures take three days and it could be easy to forget by then that they need to check for them. But these are absolutely crucial to the diagnosis of infectious diseases. ” P1 said, “I’d probably tag everything, because I like to stay on top of things in whatever way I can”. Other uses in this category include ‘tracking’ things that specifically need to be communicated verbally to other care team members, not to share the note content directly, but as P11 stated, “to note to myself to ask someone about this thing”.

Creating reusable note templates

One surprising finding was an inclination expressed by physicians to try to use our system to create templates. We had avoided a template-based GUI, based on initial physician comments, instead offering editable sections in a rich text editor to match the flexible UI of the word processing applications to which the physicians were accustomed. When introduced to the automated IR capability and activeTags, half the attending physicians studied expressed a desire to use our system to create their own templates.

These physicians mentioned that they would create sample notes with information requests as “placeholders”. The information requests would be applied to specific problems, or problem combinations. They would apply the sample notes to a patient based on problems that the patient was experiencing, and then visit each information request, setting up updates to reuse the note the next day with the most up-to-date values already inserted. P1 described how tags could help him reuse his own format: “My notes are in my own format, so I can easily recognize them. I want to create that format myself. I want to be able to do things smoothly, and decide when I put in values that I think are important, not be told what to put in and in what order.” P14 mentioned a similar use, “Patients have different profiles. For a problem, I’d probably set up a data profile, then set updates according to how important it is to monitor each, for a certain problem. This is the way I’d use updates.” This feedback points to a promising direction for future work that includes the design of technologies to enable ICU physicians to customize and personalize the UI of the information systems and documentation tools they use.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

In this paper, we described a design exploration focused on techniques to support data input and management of electronic progress note content. Our design exploration included observations, structured and semi-structured interviews, design and implementation of the activeNotes hi-fi prototype, and feedback gathered in a qualitative study with 15 ICU physicians to understand the role of tagging and IR when used with progress note documentation.

In designing activeNotes, we focused on the integration of automated, context-sensitive patient data retrieval into a note editing environment. The system automatically recognizes information requests specified in free-text in a patient progress note, interprets new note input in the context of the existing note, formulates corresponding queries, and retrieves relevant information. We introduced activeTags to explore user specification of automated updates and alerts for patient data in a note.

Feedback from our qualitative study suggests that the IR and tagging techniques were well-received. Throughout our study, physicians also proposed several uses of tags in conjunction with IR: to manage note content, specify IR preferences, communicate with other clinicians, and organize aspects of patient care. This feedback suggests several promising directions for future work related to in-depth explorations of clinical information content management and sharing among care team members. We hope to explore, in a follow-up study, whether tagging with context-sensitive information retrieval can also assist ICU physicians in the coordination of care activities, shared goals, and patient handoff.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lena Mamykina, Kathy McKeown, Peter Stetson, and Michelle Zhou for helpful discussions. We thank our study participants for their time and feedback. This work was funded in part by IBM Research under the Open Collaboration Research program.

Footnotes

General Terms

Human Factors

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames M, Naaman M. Why we tag: Motivations for annotation in mobile and online media. Proc. CHI. 2007:971–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancona M, Dodero G, Minuto F, Guida M, Gianuzzi V. Mobile computing in a hospital: The WARD-IN-HAND project. Proc. ACM Symp Applied Comp. 2000;2:554–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash JS, Gorman PN, Lavelle M, Lyman J, Delcambre LM, Maier D, Bowers S, Weaver M. Bundles: Meeting clinical information needs. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Jul;89(3):294–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bade R, Schlechtweg S, Miksch S. Connecting time-oriented data and information to a coherent interactive visualization. Proc. CHI. 2004:105–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billman D, Bier E. Medical sensemaking with entity workspace. Proc. CHI. 2007:229–32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebadollahi S, Coden AR, Tanenblatt MA, Chang S, Syeda-Mahmood T, Amir A. Concept-based electronic health records: opportunities and challenges. Proc ACM Multimedia. 2006:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eclipsys http://www.eclipsys.com/

- 8.Embi PJ, Yackel TR, Logan JR, Bowen JL, Cooney TG, Gorman PN. Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: Perceptions of faculty and resident physicians. JAMIA. 2004;11(9):300–9. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flickr http://www.flickr.com/

- 10.Frisse M, Cousins S, Hassan S. WALT: A research environment for medical hypertext. Proc. Hypertext. 1991:389–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golovchinsky G. What the query told the link: The integration of hypertext and information retrieval. Proc. Hypertext. 1997:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gresh D, Rabenhorst D, Shabo A, Slavin S. PRIMA: A case study of using information visualization techniques for patient record analysis. Proc. Visualization. 2002:509–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas J, Bright T, Bakken S, Stetson P, Johnson SB. Clinician perceptions of the usability of eNote. Proc. AMIA Symp. 2005:973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho D, et al. “Front-stage” and “back-stage” information. Proc. CHI EA. 2008:3033–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hripcsak G, Cimino J, Sengupta S. WebCIS: Large scale deployment of a web-based clinical information system. Proc. AMIA Symp. 1999:804–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh G, Lai J, Hudson S, Kraut R. Using tags to assist near-synchronous communication. Proc. CHI. 2008:223–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes G, Carr L. Microsoft smart tags: Support, ignore or condemn them? Proc. Hypertext. 2002:80–1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SB, Bakken S, Dine D, Hyun S, Mendonça E, Morrison F, Bright T, Van Vleck T, Wrenn J, Stetson P. An electronic health record based on structured narrative. JAMIA. 2008;15:54–64. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J, Zhou M. An interactive, smart notepad for context-sensitive information seeking. Proc. IUI. 2009:127–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra S, Jordan D, Shortliffe E, Patel V. Workflow modeling in critical care: Piecing together your own puzzle. J Biomed Info. 2007;40(2):81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Microsoft Amalga http://www.microsoft.com/amalga/

- 22.Müller M, Frankewitsch T, Ganslandt T, Bürkle T, Prokosch H. The clinical document architecture (CDA) enables electronic medical records to wireless mobile computing. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107(2):1448–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne T, Graham G. Managing the life cycle of electronic clinical documents. JAMIA. 2006;13:438–44. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaisant C, Mushlin R, Snyder A, Li J, Heller D, Shneiderman B. LifeLines: Using visualization to enhance navigation and analysis of patient records. Proc. CHI. 1996:221–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope C. Conducting ethnography in medical settings. Medical Education. 2005;39(12):1180–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Practice Partner http://www.practicepartner.com.

- 27.Reddy M, Pratt W, Dourish P, Shabot MM. Asking questions: Information needs in a surgical intensive care unit. Proc. AMIA. 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy M, Dourish P. A finger on the pulse: Temporal rhythms and information seeking in medical work. Proc. CSCW. 20022002:344–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhodes B, Starner T. Remembrance agent: A continuously running information retrieval system. Proc. Conf. Pract. App Intell. Agents. 1996:487–495. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbloom S, Grande J, Geissbuhler A, Miller R. Experience in implementing inpatient clinical note capture via a provider order entry system. JAMIA. 2004;11(4):310–15. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos-Neto E, Condon D, Andrade N, Iamnitchi A, Ripeanu M. Individual and social behavior in tagging systems. Proc. Hypertext. 2009:183–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang C, Carpendale S. An observational study on information flow during nurses’ shift work. Proc. CHI. 2007:219–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang PH, editor. Key capabilities of an electronic health record system. Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; Washington DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Kleek MG, Bernstein M, Panovich K, Vargas GG, Karger DR, Schraefel M. Note to self: Examining personal information keeping in a lightweight note-taking tool. Proc. CHI. 2009:1477–80. [Google Scholar]

- 35.VISICU eICU® eCareManager. http://www.visicu.com/products/evantagesystem.html.

- 36.Wang TD, Plaisant C, Quinn AJ, Stanchak R, Murphy S, Shneiderman B. Aligning temporal data by sentinel events: discovering patterns in electronic health records. Proc. CHI. 2008:457–66. [Google Scholar]

- 37.WebCIS https://webcis.nyp.org/

- 38.Weir C, Hurdle J, Felgar M, Hoffman J, Roth B, Nebeker J. Direct text entry in electronic progress notes. An evaluation of input errors. Methods Inf Med. 2003;42(1):61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou MX, Houck K, Pan S, Shaw J, Aggarwal V, Wen Z. Enabling context-sensitive information seeking. Proc. IUI. 2006:112–123. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou X, Ackerman MS, Zheng K. I just don’t know why it’s gone: Maintaining informal information use in inpatient care. Proc. CHI. 2009:2061–70. [Google Scholar]