Abstract

Despite recent advancements in large-scale phospho-proteomics, methods to quantify kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry of protein substrates are lacking. We developed a method to quantify kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry by combining the reverse in-gel kinase assay (RIKA) with high resolution LC-MS. Beginning with predetermined ratios of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated Protein Kinase CK2 (CK2) substrate molecules, we employed 18O-ATP as the phosphate donor in a RIKA, then quantified the ratio of 18O-versus 16O-labeled tryptic phosphopeptide using high mass accuracy MS. We demonstrate that the phosphorylation stoichiometry determined by this method across a broad percent phosphorylation range correlated extremely well with the predicted value (correlation coefficient =0.99). This approach provides a quantitative alternative to antibody-based methods of determining the extent of phosphorylation of a substrate pool.

Keywords: Phosphorylation Stoichiometry, Kinase specific, Stable Isotope Labeling, Kinase Substrates

INTRODUCTION

Reversible protein phosphorylation regulates essentially all cellular activities. Aberrant protein phosphorylation is an etiological factor in a wide array of diseases, including cancer1, diabetes2, and Alzheimer’s3. Given the broad impact of protein phosphorylation on cellular biology and organismal health, understanding how protein phosphorylation is regulated and the consequences of gain and loss of phosphoryl moieties from proteins is of primary importance. Advances in instrumentation, particularly in mass spectrometry, coupled with high throughput approaches have recently yielded large datasets cataloging tens of thousands of protein phosphorylation sites in multiple organisms4–6. While these studies are seminal in terms of data collection, our understanding of protein phosphorylation regulation remains largely one-dimensional.

Phosphoproteomics encompasses a highly complex, multi-dimensional network7,8,9, with kinases and phosphatases occupying primary nodal positions. Protein kinases and their substrates form the basic units of interaction in this network. The network is further connected hierarchically through the phosphorylation of kinases by upstream activating kinases10. It is through this network that cellular signals are received, and responses executed, rapidly and accurately. Despite the acquisition of large phosphopeptide datasets, detailed knowledge of the connections that constitute the phosphoproteomic network is rudimentary, since kinase-substrate relationships for nearly all kinases have been only partially described, if at all11, despite the fact that technical advances have been made in methods to discern kinase-substrate relationships 12–18.

With recent advances in mass spectrometry, both small19–21 and large-scale measurement of general phosphorylation stoichiometry is now readily achievable22–24. However, these studies do not broadly reveal kinase-substrate relationships. A method to measure kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry would be highly useful as a basic research tool and to monitor changes in phosphorylation in patient samples. Here, we report a new application of the Reverse In-gel Kinase Assay (RIKA) to advance the technology toward this goal.

The RIKA was first developed to profile substrates of any kinase that can be refolded to a catalytically active state after denaturing gel electrophoresis25. The kinase is polymerized into the gel then refolded together with resolved proteins. This gel-based approach has been demonstrated to be superior to solution-based strategies since it essentially eliminates the confounding effects of kinases, phosphatases, and ATPases present in complex protein extracts. RIKAs have been successfully developed for six different serine-threonine kinases. While not applicable to all kinases (i.e. multi-subunit enzymes) the data published to date bode well for its utility to profile physiological substrates of many. To address the accuracy of the RIKA, we previously demonstrated using a Protein Kinase CK2 (CK2)-specific inhibitor that 97% of CK2 substrates detected in a RIKA became hypo-phosphorylated after 30 minutes of inhibitor exposure in live cells, while Protein Kinase A substrates were unchanged25. We also showed that the RIKA can be employed to measure dynamic changes in kinase substrate phosphorylation, however, the approach was cumbersome and required the use of ionizing radioisotopes26.

In this report, using Protein Kinase CK2 (CK2) as a paradigm, we describe a new approach to determine kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry of mono-phosphorylated peptides across a wide dynamic range. Using high mass accuracy mass spectrometry coupled with stable isotope labeling in RIKAs, we demonstrate that it is feasible to accurately measure phosphorylation stoichiometries. This work establishes a new approach for determining the phosphorylation status of a kinase substrate pool that obviates the need for anti-phosphosite antibodies.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Measuring 18O:16O phosphorylation ratio by LC-MS

Separations were performed on a custom-built LC system using two Agilent series 1260 LC pumps (Santa Clara, CA), a PAL auto-sampler (Leap Technologies, Carrboro, NC), and automated using custom software27. Reversed-phase analytical columns were prepared in-house by slurry packing 3 μm Jupiter C18 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) into a 60 cm long, 75 μm i.d. and 360 μm o.d. fused silica capillary (Polymicro technologies, Phoenix, AZ). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solution A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solution B) pumped at ~300 nL/min with a gradient profile as follows (minute: percentage of solution B): 0:5%, 2:8%, 20:12%, 75:30%, 97:45%, 100:95%. Sample loading was achieved using Valco valves (Valco Instruments Co., Houston, TX) with a 5 μL sample loop.

Mass spectra were acquired on a Thermo Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) equipped with subamibient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) source. The SPIN source consists of a dual ion funnel interface with a chemically etched ESI emitter positioned at the entrance of the high pressure ion funnel inside the first vacuum region of the instrument as described in detail previously28,29. The instrument was operated in ultra-high resolution mode (~75,000) with a full scan m/z range of 400–2000. Each spectrum was averaged across the LC eluting peak corresponding to each specific phosphopeptide pair. Peak height in the spectrum was used for peak intensity comparison. Due to a significant 6 Da mass shift and sufficiently high MS resolution, the contribution of isotopic overlap between 18O and 16O for 3+ phosphopeptide to each mono isotope peak intensity should be negligible. Three micro scans were used to average each spectrum. The AGC was set for high dynamic range with a maximum ion injection time of 100 ms. The 18O:16O phosphorylation ratio was determined by the corresponding peak intensity ratio obtained from the average mass spectrum across the analyte peak in extracted ion chromatogram.

Measuring telomerase binding protein (TEBP) phosphorylation efficiency by LC-MS

Tryptic peptides of TEBP extracted from the RIKA gels were analzyed on a Synapt G2S HDMS system coupled with a nanoAcquity UPLC system under the control of MassLynx software (Waters). The tryptic peptides were trapped and desalted on-line by using a nanoACQUITY BEH C18 trapping column (Waters). Desalted peptides were separated on a nanoACQUITY UPLC analytical column (BEH130 C18, 1.7 μm, 75 μm x 150 mm, Waters) by a 180 min linear acetonitrile gradient (3 – 43%) with 0.1 % formic acid at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The eluent was directed into the ion source of the coupled Synapt G2S HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters). Mass spectra were acquired in the MSE mode over the m/z range of 50–2000. During data acquisition, the collision cell energy alternated between low energy (4 eV) and elevated energy setting (energy ramped from 19 to 45 eV). The scan time was 0.6 s in both acquisition modes (1.3 s total duty cycle). In this configuration, the spectra of all peptide precursor ions (MS1) and corresponding fragmentation product ions (MS2) were acquired in parallel. Other mass spectrometer parameters were as follows: electrospray ionization positive (ESI+) mode, capillary voltage 3.5 kV, sampling cone voltage 26 V, source temperature 80°C. For mass accuracy reference, leucine-enkephalin was infused through the reference fluidics system of the Synapt G2S and sampled every 30 s as the lock mass.

Raw data were loaded into ProteinLynx Global Server (Waters), and peaks were resolved via Apex3D and Peptide3D algorithms using a low energy threshold at 250 counts, an elevated energy threshold at 100 counts, and an intensity threshold of precursor/fragment ion cluster at 750 counts. The precursor ions from the low-energy scan and corresponding fragment ions from the elevated-energy scan were aligned by the retention time profile of each ion. Peptides were identified by the ion accounting algorithm searching against TEBP and its decoy sequence using the following parameters: precursor tolerance 5 ppm, fragment tolerance 13 ppm, minimum 3 fragment ion matches per peptide, maximum 2 missed tryptic cleavages, variable methionine oxidation (+15.9949), enriched phosphorylation (STY) and a maximum false discovery rate at 1 %. To determine the extent of phosphorylation of TEBP, raw spectra were de-convoluted and de-isotoped as described30 to facilitate the calculation.

RESULTS

Using stable isotope labeling in RIKA to measure kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry

To facilitate using RIKA as a tool to measure kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry, we employed γ-18O-ATP31 as the phosphate donor. In a RIKA, the unoccupied fraction of protein phosphoacceptor sites is labeled in a manner termed back phosphorylation. Back phosphorylation is a classical method for measuring phosphorylation using γ-32P-ATP in an in vitro kinase reaction with a partially purified substrate 32. In a RIKA, the back phosphorylation with γ-18O-ATP occurs in-gel after resolution by PAGE in a kinase-laden gel. To illustrate, consider an example where nine molecules of a substrate are present in the gel, and where six were already naturally phosphorylated with 16O-phosphate when extracted (Figure 1, upper panel). In that case, only the three remaining molecules could potentially be labeled in the RIKA. If γ-18O-ATP is used as the phosphate donor in the RIKA, and complete phosphorylation is achieved, those three molecules would become labeled with 18O-phosphate. After the substrates in the gel are trypsin-digested and analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry, the ratio of 16O-phosphate labeled peptide and 18O-phosphate labeled peptide would be 6:3. The original phosphorylation stoichiometry can then be determined as 16O-phosphate/16O-phosphate+18O-phosphate, 6/(6+3) = 66.7%.

Figure 1. Measurement of kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry.

Circles represent protein molecules that are substrates of a given kinase. Top left: Of nine substrate molecules six are shown as phosphorylated (red,16P). After phosphorylation to completion in a RIKA, the remaining three substrate molecules become labeled with 18O-phosphate (Top right, 18P). Phosphopeptides enriched after tryptic digestion are analyzed by LC-MS. The ratio of 16O-phosphorylated peptide to 18O-phosphorylated peptide is 6:3, from which the absolute phosphorylation stoichiometry is calculated to be: [6/(6+3)]*100%=66.7%. Bottom left: When the kinase activity is partially inhibited, two more substrate molecules in the pool of nine are not phosphorylated. In this case, the measured 16O:18O ratio would be 4:5; and phosphorylation stoichiometry = 44.4%.

Determining the phosphorylation stoichiometry of specific proteins under conditions where kinase activity is targeted by an inhibitor could provide key insights into inhibitor efficacy and substrate responsiveness. For example, if kinase activity within the cells is inhibited (Figure 1, lower panel), and the number of phosphorylated molecules of a particular substrate decreases in vivo from six to four, the 16O:18O ratio in a stable-isotope RIKA would change from 6:3 to 4:5, reflecting a change in phosphorylation stoichiometry from 67% to 44%. This change, together with fact that the substrate is directly phosphorylated by the kinase in RIKA, would strongly indicate that this substrate is an in vivo substrate of the kinase targeted by the inhibitor33. Such a subtle change would be difficult to quantify using a conventional phospho-specific/total antibody approach, but could be both biologically and clinically significant.

Determining the accuracy of 16O-phosphate:18O-phosphate ratio quantification using high-resolution LC-MS

To demonstrate the accuracy of measuring the 16O-phosphate:18O-phosphate ratio of a phosphopeptide using high-resolution LC-MS, we created a series of samples with known ratios by first phosphorylating telomerase binding protein (TEBP) in vitro using CK2 in the presence of either 16O-ATP or γ-18O-ATP. Near complete phosphorylation of TEBP was achieved as evidenced by the lack of back phosphorylation of TEBP in a subsequent CK2 RIKA (Figure S1, supporting information). 16O- and 18O-labeled TEBP was then mixed in known ratios to create a series of samples containing 100%, 80%, 20% and 0% 16O-phosphorylated TEBP. Phosphorylated TEBP was resolved on a conventional SDS-PAGE gel, excised, and digested with trypsin. Extracted peptides were then analyzed by high resolution LC/MS.

Two TEBP tryptic phosphopeptides were detected, singly phosphorylated AA108–122 (DWEDDSpDEDMSNFDR), and doubly phosphorylated AA123–155 (FSEMMNNMGGDEDVDLPEVDGADDDSpQDSpDDEK). Singly phosphorylated AA108–122 eluted in a single peak in which the 2+ and 3+ ions were detected and the 16O:18O peak ratio was readily quantifiable. Doubly phosphorylated AA123–155 failed to elute in a single peak during reverse-phase LC, precluding quantification, and was not considered further. It is not clear if this reflects a general property of doubly phosphorylated peptides or whether it is unique to TEBP AA123–155. The MS spectra obtained for the singly phosphorylated AA108–122 3+ ion for the samples containing 80% and 20% 16O-phosphorylated TEBP are shown in Figure 2, and spectra for additional samples are shown in Figure S2 (supporting information). Table S1 (supporting information) summarizes the observed relative abundance ratios for the 16O and 18O phosphorylated peptide for both charge states. In all cases, the relative abundances of the 16O and 18O peaks for the 2+ and 3+ ions were nearly identical, suggesting a high degree of precision. For the charge 3+ ion, when the 16O percentage was fixed at 100%, the 16O-phosphate-labeled peptide was assigned a relative abundance of 100. Although no 18O-labeled TEBP was experimentally added to this sample, 18O-phosphorylated peptide was detected, at a relative abundance of 0.2. It is likely that this small amount of 18O-phosphorylated peptide arises from naturally existing 18O, which accounts for 0.2% of total oxygen.

Figure 2. Measuring 18O:16O phosphorylation ratio by LC-MS.

Representative LC-MS spectrum measuring 16O:18O phosphorylation ratio for peptide 108–122 DWEDDSDE (Sp) DEDMSNFDR from TEBP. This ion is 3+ charged, with a m/z value of 652.55 for the 16O-phosphorylated form, and a m/z value of 654.55 for the 18O-phosphorylated form. A. Spectrum for a premixed 8:2 ratio. The measured ratio is 100:21; and the expected value is 100:25. B. Spectrum for 2:8 ratio. The measured value is 31.5:100, and the expected value is 25:100. Arrows, phosphorylated ion peaks. Relative abundance values are indicated in parentheses.

Generating a sample with 0% 16O-phosphorylated TEBP presents a technical challenge due to the presence of 16O contamination in commercial preparations of 18O-ATP. Currently available production methods yield 18O-ATP with purity in the range of 97%. Thus, a TEBP sample phosphorylated to completion in the presence of 97% pure 18O-ATP should yield an AA108–122 peptide with a maximum of 3% of 16O-phosphorylation. When the sample containing 0% 16O-phosphorylated peptide was analyzed, the percentage was observed to be 0.8%, which was in the expected range. In the samples containing 80% and 20% 16O-phosphorylated TEBP, the relative abundance matched well with the expected value after adjusting for γ-18O-ATP purity (see Table 1 legend for purity adjustment calculation). The data shown in Figure 2 and Table S1 (supporting information), demonstrate that the 16O:18O phosphorylation ratio for the singly phosphorylated TEBP peptide can be reliably measured and quantified.

Table 1. Expected versus measured values of 16O and 18O-labeled phosphorylation stoichiometry standards determined by RIKA and LC/MS.

The LC-MS data for a range of stoichiometries for the AA108–122 peptide are summarized. The expected stoichiometry values were adjusted to account for 18O-ATP purity (assuming the 3% impurity is 16O-ATP) and are shown in parentheses. Purity adjustment is performed using the following logic: when the expected stoichiometry is a, the adjusted value will be a+(1-a)*(100%-percent 18O-ATP purity). In this case, the purity of 18O-ATP was 97%. The measured stoichiometry is determined from the relative abundance of the 16O and 18O-phosphorylated peptide for both the 2+ and 3+ charges states observed from the mass spectrum. When the ratio of 16O-phosphorylated peptide to 18O-phosphorylated peptide is X, the stoichiometry is derived as 100%* X/(1+X). Measured stoichiometry calibrated to account for the completeness of phosphorylation in RIKA was presented in the parenthesis in the same column. Calibration is performed using the following logic: When the abundance for 16O-phosphorylated peptide is a, and the 18O-phosphorylated abundance is b, the calibrated stoichiometry is a/(a+b/95%). 95% represents the completeness of phosphorylation in the CK2 RIKA. The average value between the two charge states and the percent error for the measured value relative to the expected value after adjusting for γ-18O-ATP purity are indicated.

| 3+ | 2.2 | 100 | 2.2% (2.0%) | |

| Ave | 2.5 | 100 | 2.5% (2.3%) | |

| Err | 16.7% (23.3%) | |||

| 10% (12.7%) | 2+ | 19.2 | 100 | 16.1% (15.4%) |

| 3+ | 18.0 | 100 | 15.3% (14.6%) | |

| Ave | 18.6 | 100 | 15.7% (15.0%) | |

| Err | 23.6% (18.1%) | |||

| 20% (22.4%) | 2+ | 35.8 | 100 | 26.4% (25.4%) |

| 3+ | 36.5 | 100 | 26.7% (25.8%) | |

| Ave | 36.2 | 100 | 26.6% (25.6%) | |

| Err | 18.8% (12.5%) | |||

| 40% (41.8%) | 2+ | 93.2 | 100 | 48.2% (47.0%) |

| 3+ | 93.0 | 100 | 48.2% (47.0%) | |

| Ave | 93.1 | 100 | 48.2% (47.0%) | |

| Err | 15.3% (12.4%) | |||

| 50% (51.5%) | 2+ | 100 | 73.5 | 57.6% (56.4%) |

| 3+ | 100 | 72.5 | 58.0% (56.7%) | |

| Ave | 100 | 73.0 | 57.8% (56.6%) | |

| Err | 12.2% (9.5%) | |||

| 60% (61.2%) | 2+ | 100 | 47.2 | 67.9% (66.8%) |

| 3+ | 100 | 48.2 | 67.5% (66.3%) | |

| Ave | 100 | 47.7 | 67.7% (66.5%) | |

| Err | 10.6% (8.7%) | |||

| 80% (80.6%) | 2+ | 100 | 15.0 | 87.0% (86.4%) |

| 3+ | 100 | 15.8 | 86.4% (85.7%) | |

| Ave | 100 | 15.4 | 86.7% (86.1%) | |

| Err | 7.5% (6.8%) | |||

| 90% (90.3%) | 2+ | 100 | 6.9 | 93.5% (93.2%) |

| 3+ | 100 | 6.2 | 94.2% (93.9%) | |

| Ave | 100 | 6.6 | 93.9% (93.6%) | |

| Err | 3.9% (3.7%) | |||

| 100% | 2+ | 100 | 0 | 100% (100%) |

| 3+ | 100 | 0 | 100% (100%) | |

| Ave | 100 | 0 | 100% (100%) | |

| Err | 0% (0%) |

Kinase substrates are quantitatively phosphorylated in RIKA

Having demonstrated that accurate LC/MS quantification of 16O:18O-phosphate ratio after conventional in vitro phosphorylation is possible, we sought to determine if the same could be achieved for a substrate in a RIKA gel. To be capable of quantifying phosphorylation stoichiometry using the RIKA approach, nearly quantitative phosphorylation in a RIKA gel is required. To demonstrate that TEBP can be phosphorylated to near completion in a RIKA, we performed assay with a gel containing 20 μg/ml CK2 and in the presence of 50 μM ATP (Figure 3A, left panel). A mock RIKA with 20 μg/ml CK2 in the gel but no ATP in the reaction buffer was carried out in parallel. After two hours incubation in reaction buffer, the gels were stained with Coomassie blue to stop the reaction. The TEBP band was excised and dispersed into polyacrylamide particles (diameter <0.1 mm) using a hand-held rotor-stator homogenizer. TEBP was extracted and analyzed in a second RIKA using γ-32P-ATP as the phosphate donor. If TEBP is completely phosphorylated in a RIKA gel, then it should not become isotopically labeled by back phosphorylation in a second RIKA since all of the phosphoacceptor sites will already be occupied. In contrast, the phosphoacceptor sites in TEBP from the mock RIKA (no ATP) will be unoccupied, and thus can be robustly back phosphorylated in the second RIKA. The data shown in Figure 3A (Figure 3A, right panel) demonstrate that, as expected, the TEBP extracted from the mock (no ATP) gel became robustly labeled in the subsequent RIKA, whereas the TEBP extracted from the RIKA gel with 50 μM ATP did not. To facilitate comparison of signal intensities generated from the non-phosphorylated (control) and phosphorylated TEBP in the second RIKA, a tenfold-dilution of each was analyzed in parallel with undiluted samples. The signal generated from the undiluted phosphorylated sample was considerably lower than a 10-fold dilution of the control, indicating that the reaction was >90% complete.

Figure 3. CK2 substrates are quantitatively phosphorylated in RIKA.

A. TEBP is phosphorylated close to completion in RIKA. ~10 μg recombinant TEBP was analyzed in a CK2 RIKA (20 μg/ml in gel, 50 μM 16O-ATP in reaction buffer) (left panel). A control gel without ATP was analyzed in parallel (not shown). To determine the extent of TEBP phosphorylation, the Coomassie blue-stained TEBP band was excised and homogenized. TEBP was extracted and analyzed in a second RIKA (right panel) with 32P-ATP as the phosphate donor. A 10-fold dilution of extracted TEBP was included to facilitate evaluation of phosphorylation efficiency. Lanes 1&2, 3&4, 5&6, and 7&8 are technical replicates. B&C. Measuring the efficiency of phosphorylation of TEBP in RIKA by using label-free LC-MS. B. The spectrum and intensities of the precursor ions for the reference peptide (gray), and for the non-phosphorylated peptide (blue) in the control gel. Raw spectra were de-convoluted and de-isotoped as described in the experimental section. C. The intensities of the precursor ions for the reference peptide (gray), the non-phosphorylated peptide (blue), and the phosphorylated peptide in the experimental gel.

To further confirm that nearly complete phosphorylation of TEBP was achieved in CK2 RIKA, we quantified the percentage of phosphorylation of peptide DWEDDSDEDMSNFDR by using LC-MS (Table S2, supporting information, and Figure 3B&C) in a label-free manner34. TEBP from experimental RIKA and control gels was excised, trypsin digested, and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. An internal peptide, DVNVNFEK, which is not phosphorylated by CK2, was used for normalization. Five precursor ions were detected for peptide DWEDDSDEDMSNFDR. Due to oxidation on the methionine, two precursor ions were detected for the non-phosphorylated peptide (oxidized and non-oxidized). The major CK2 phosphorylation site in this peptide is the first serine residue (Figure 3C, peaks 3 and 97.2 % intensity of peak 4). The second serine residue in this peptide was also detected to be phosphorylated with very low stoichiometry, accounting for ~1% of the total phosphorylated peptide (Figure 3C, peak 5, and 2.8 % intensity of peak 4). The results demonstrated that 88.4% (Table S2, supporting information) of the dominantly phosphopeptide was phosphorylated, slightly lower than that measured by RIKA (Figure 3A). Interference from methionine oxidation is likely to contribute to the small difference in these measurements. To demonstrate that complete substrate phosphorylation in a RIKA is not unique to recombinant TEBP, recombinant purine rich element binding protein B (PURB) was phosphorylated in a CK2 RIKA and analyzed by LC/MS as described above for TEBP. The non-phosphorylated form of the target peptide was not detected (Figure S3, supporting information) demonstrating complete phosphorylation.

To measure the degree of phosphorylation completeness across a broad spectrum of substrates in a CK2 RIKA, a fractionated HeLa extract was analyzed in a two-stage RIKA. The first stage RIKA was performed in the presence of excess cold ATP. Using γ-32P-O-ATP in the second stage RIKA permitted quantification of the extent of back phosphorylation, which reflects the amount of substrate that failed to become phosphorylated in the first stage RIKA. As shown in Figure S4, (Figure S4, supporting information), minimal back phosphorylation was observed, strongly suggesting that the nearly all substrates in the HeLa extract were phosphorylated to near completion in the first stage RIKA. To demonstrate that efficient phosphorylation in a RIKA is not a feature unique to CK2, a fractionated K652 whole cell lysate was analyzed in a two-stage PIM1 kinase RIKA. The data shown in Figure S5 (Figure S5, supporting information) demonstrate that PIM1 substrates are also phosphorylated to near completion in a RIKA.

The phosphorylation efficiency in the kinase reaction of a RIKA will clearly impact the accuracy of phosphorylation stoichiometry measurements. To predict the measurement error rate created by incomplete phosphorylation in a RIKA, we calculated theoretical measured values for different stoichiometries under various phosphorylation efficiencies (Table S3, supporting information). For a given phosphorylation efficiency, the error rate increases as the substrate phosphorylation stoichiometry decreases. Based on the well-established Krebs and Beavo criteria35,36, we anticipate that true physiological substrates will be robustly phosphorylated by a given kinase. Krebs and Beavo suggested that bona fide kinase substrates should be essentially completely phosphorylated in vitro. This criterion has been substantiated in extensive analyses with many kinases and substrates33,37,38. The fact that a substantial proportion of endogenous proteins have phosphorylation stoichiometries >90% in both yeast22 and human23 cells also suggests that bona fide kinase substrates are capable of being phosphorylated to near completion. We have observed that substrates of multiple kinases, including CK2 and Pim1 can be phosphorylated to near completion in RIKAs (Figures S4 and S5, supporting information). For each kinase, it will likely be necessary to optimize in-gel kinase activity and ATP concentration to achieve the highest possible phosphorylation efficiency.

To further explore parameters affecting phosphorylation efficiency we performed a series of assays varying the CK2 concentration in the gel, and the ATP concentration in the kinase reaction buffer. When the CK2 concentration in the gel was relatively high (100 μg/ml), a relatively low ATP level (2 μM) was sufficient to support ~90% phosphorylation efficiency of TEBP (Figure S6, supporting information). In contrast, when the CK2 concentration was relatively low (20 μg/ml), this level of efficiency was achieved only when the ATP concentration was 10 μM or above (Figure S6, supporting information). To ensure complete phosphorylation, 20 μg/ml CK2 and 100 μM ATP in the reaction buffer were chosen as standard reaction conditions.

Determining accuracy of phosphorylation stoichiometry quantification using the RIKA

After confirming that 16O:18:O ratio can be accurately measured, and that nearly complete phosphorylation of substrates is achievable in a RIKA, we sought to determine whether kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry could be accurately quantified using this approach. We created a series of substrate samples with known phosphorylation stoichiometry by mixing CK2-phosphorylated, and non-phosphorylated TEBP. To generate these standards, TEBP was exhaustively phosphorylated with CK2 in the presence of excess γ-16O-ATP. A parallel mock reaction was also set up with no ATP. We determined the completeness of the in vitro kinase assay by analyzing both the experimental reaction and the mock reaction in a CK2 RIKA using γ-32P-ATP as phosphate donor. By comparing signal intensities among undiluted and 10-fold diluted samples, we determined that the labeling efficiency was approximately 90% (Figure S7A, supporting information). Based on these results, we created a series of samples with known phosphorylation stoichiometry by mixing experimental kinase assay products with mock in vitro kinase assay products such that the final contribution of phosphorylated TEBP would be 0%, 10%, 20%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 80%, and 90%.

To analyze this series of samples with known stoichiometry, the mixtures were processed in a CK2 RIKA reaction following the standard optimized CK2 RIKA reaction conditions with γ-18O-ATP as the phosphate donor. After overnight incubation, the reaction was stopped by staining with Coomassie blue (Figure S7B, supporting information). To determine the completeness of the reactions, bands containing TEBP from the 0% phosphorylation stoichiometry sample were excised from the gel, homogenized, extracted, and analyzed in a second CK2 RIKA with γ-32P-ATP as the phosphate donor. Comparison of signal intensities generated from 10-fold, 50-fold, and undiluted samples demonstrated that the phosphorylation efficiency in RIKA was >90% (Figure S7C, supporting information). This high phosphorylation efficiency bodes well for the accurate measurement of phosphorylation stoichiometry in this system.

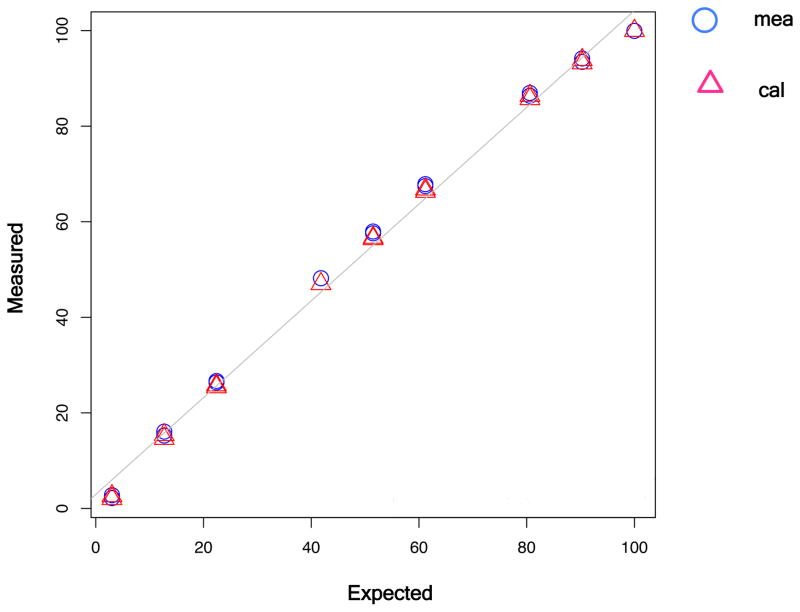

To quantify the stoichiometry using high resolution LC-MS, TEBP from the phosphorylation standard series was excised from a RIKA gel and digested with trypsin. Phosphorylated peptides were enriched using Fe3+-IMAC chromatography and analyzed by high-resolution LC-MS. The data for quantification of the 2+ and 3+ ions of AA108–122 from the stoichiometry standard series are summarized in Table 1, and the observed mass spectra for all samples are shown in Figure S8 (Figure S8, supporting information). The measured stoichiometry correlated well to the expected values with remarkable accuracy across the entire range (0%–90%) of phosphorylation stoichiometry (Figure 4). Deviation from expected values correlated inversely with phosphorylation stoichiometry. Maximal deviation (23%) was observed in the 0% phosphorylation sample, which was expected to yield a measured value of 3% due to the fact that the 18O-ATP is only 97% pure. The measured value in that sample was 2.3%. In contrast, the 90% expected sample (90.3% after adjusting for 18O-ATP purity) yielded a measured value to 93.6, a 6.6% deviation from expected. The correlation coefficient across all stoichiometries measured was >0.99 (Figure 4). These data demonstrate that this RIKA-based method can reliably detect a 10% increase in kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry across a wide dynamic range (10% to 90% phosphorylation) with an error rate of 4 to 20%. The robust performance of this approach is due in part to the fact that it measures both a phosphorylated and previously non-phosphorylated peptide simultaneously in one ratio. Currently, two other methods are available to measure large-scale general phosphorylation stoichiometry. One involves peptide dephosphorylation with phosphatase followed by chemical labeling with stable isotope. This method has a limited dynamic range, given that it only measures change in the non-phosphorylated portion of the peptide pool22. A second method involves the use of metabolic labeling with stable isotope and measuring the ratios of phosphorylated, non-phosphorylated, and total peptides23. Errors in any of the three values may significantly impact accuracy.

Figure 4. CK2-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry can be accurately quantified.

Stoichiometry values obtained by quantitative MS were plotted against expected values (after adjustment for 18O-ATP purity) for the TEBP stoichiometry standards. Values with (triangles), and without (circles) calibration (cal) for RIKA efficiency are shown. In both cases, measured values matched well with the expected values with correlation coefficients of 0.997 (measured) and 0.998 (calibrated).

With the exception of the 0% phosphorylation condition, we observed that the measured CK2-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry was slightly higher than expected. One possible reason is that the phosphorylation reaction was not driven to completion. It is also possible that spontaneous conversion of 18O-phoshorylated peptide to 16O-phosphorylated peptide due to oxygen exchange may be a contributing factor. It has been reported that this conversion occurs at a considerable rate at the presence of beta glycerol phosphate in in vitro kinase reactions31. This conversion was also observed in reaction conditions that are similar to that in a cell in the presence of a complex milieu of enzymes and metabolites39. We did not observe obvious conversion under standard RIKA conditions, which is in agreement with the results from previous studies in simple aqueous environments31,40.

Conclusions

The ability to rapidly quantify kinase-specific phosphopeptide stoichiometry would provide a powerful tool to determine the functional consequences of dynamic changes in phosphorylation in cells. Accurate measurement of phosphorylation stoichiometry for protein kinase substrates would also provide critically needed pharmacodynamic biomarkers41–43 for the burgeoning number of kinase inhibitors in the drug development pipeline1,44,45. Ideally, these biomarkers would be direct physiological substrates of the drug-targeted kinase that would respond to the presence of the inhibitor. We describe here proof-of-concept for a novel approach to accurately quantify kinase-specific phosphorylation stoichiometry using a model substrate. The utility of this system is dependent upon recovering kinase activity after in-gel refolding, and on the ability of the kinase to efficiently phosphorylate its substrates. To date, we have already demonstrated that both of these criteria can be readily achieved by a diverse set of serine-threonine kinases including CK2, PKA, ERK2, Aurora A, and GSK3β25,46,47. With the exception of a limited number of kinases that require multiple subunits to be active, for example, cyclin-dependent, and membrane localized kinases, most kinases would be expected to function in a RIKA. Further development of this approach may permit simultaneous measurement of phosphorylation stoichiometry for multiple substrates in complex protein extracts, leading to the identification of pharmacodynamic biomarkers of clinically relevant kinase inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants R21CA155568 (Innovative Molecular Analysis Technologies Program) and R21CA199042 to C.J.B. from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Work related to the SPIN-MS sample analysis was supported by the NIH National Cancer Institute (R21CA155568) as well as the General Medical Sciences (FM103491-12), and by the Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research Genome Sciences Program under the Pan-omics project. SPIN-MS data were collected at the Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory, a U. S. Department of Energy (DOE) national scientific user facility located at PNNL in Richland, Washington. PNNL is a multiprogramming national laboratory operated by Battelle for the DOE under contract DE-AC05-76RLO01830.

Footnotes

Data showing the accuracy of phosphorylation stoichiometry measurement and a theoretical consideration of the effects of catalytic efficiency on that value, data showing that substrates are phosphorylated nearly to completion in RIKAs.

References

- 1.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prada PO, Saad MJ. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:751–763. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.802768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tell V, Hilgeroth A. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:189. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Haas W, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. Cell. 2010;143:1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok J, Zhu X, Snyder M. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8:775–786. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu J, Rho HS, Newman RH, Hwang W, Neiswinger J, Zhu H, Zhang J, Qian J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1844:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu J, Rho HS, Newman RH, Zhang J, Zhu H, Qian J. Bioinformatics. 2013;30:141–142. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman RH, Hu J, Rho HS, Xie Z, Woodard C, Neiswinger J, Cooper C, Shirley M, Clark HM, Hu S, Hwang W, Jeong JS, Wu G, Lin J, Gao X, Ni Q, Goel R, Xia S, Ji H, Dalby KN, Birnbaum MJ, Cole PA, Knapp S, Ryazanov AG, Zack DJ, Blackshaw S, Pawson T, Gingras AC, Desiderio S, Pandey A, Turk BE, Zhang J, Zhu H, Qian J. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:655. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson SA, Hunter T. Nat Methods. 2005;2:17–25. doi: 10.1038/nmeth731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen P, Knebel A. Biochem J. 2006;393:1–6. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah K, Shokat KM. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;233:253–271. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-397-6:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue L, Arrington JV, Tao WA. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1355:263–273. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3049-4_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amano M, Hamaguchi T, Shohag MH, Kozawa K, Kato K, Zhang X, Yura Y, Matsuura Y, Kataoka C, Nishioka T, Kaibuchi K. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:895–912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok J, Im H, Snyder M. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1820–1827. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson SM, White FM. Sci Signal. 2012;5:pl3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bian Y, Ye M, Wang C, Cheng K, Song C, Dong M, Pan Y, Qin H, Zou H. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3460. doi: 10.1038/srep03460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin LL, Tong J, Prakash A, Peterman SM, St-Germain JR, Taylor P, Trudel S, Moran MF. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2752–2761. doi: 10.1021/pr100024a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson H, Eyers CE, Eyers PA, Beynon RJ, Gaskell SJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:2211–2220. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu R, Haas W, Dephoure N, Huttlin EL, Zhai B, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. Nat Methods. 2011;8:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen JV, Vermeulen M, Santamaria A, Kumar C, Miller ML, Jensen LJ, Gnad F, Cox J, Jensen TS, Nigg EA, Brunak S, Mann M. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai CF, Wang YT, Yen HY, Tsou CC, Ku WC, Lin PY, Chen HY, Nesvizhskii AI, Ishihama Y, Chen YJ. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6622. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Guan B, Srivastava MK, Padmanabhan A, Hampton BS, Bieberich CJ. Nat Methods. 2007;4:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Rao V, Jin J, Guan B, Anderes KL, Bieberich CJ. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:3637–3649. doi: 10.1021/pr3000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livesay EA, Tang K, Taylor BK, Buschbach MA, Hopkins DF, LaMarche BL, Zhao R, Shen Y, Orton DJ, Moore RJ, Kelly RT, Udseth HR, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2008;80:294–302. doi: 10.1021/ac701727r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page JS, Tang K, Kelly RT, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1800–1805. doi: 10.1021/ac702354b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marginean I, Page JS, Tolmachev AV, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 2012;82:9344–9349. doi: 10.1021/ac1019123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wehofsky M, Hoffmann R. J Mass Spectrom. 2002;37:223–229. doi: 10.1002/jms.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, Meng Z, Jobson AG, Pommier Y, Veenstra TD. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7603–7610. doi: 10.1021/ac071584r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mundina-Weilenmann C, Chang CF, Gutierrez LM, Hosey MM. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4067–4073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berwick DC, Tavare JM. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong JW, Cagney G. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:273–283. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-444-9_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rider MH, Waelkens E, Derua R, Vertommen D. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2009;115:298–310. doi: 10.3109/13813450903338108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krebs EG, Beavo JA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:923–959. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.004423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dephoure N, Gould KL, Gygi SP, Kellogg DR. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:535–542. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wegener AD, Jones LR. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1834–1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molden RC, Goya J, Khan Z, Garcia BA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:1106–1118. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.036145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phelan VV, Du Y, McLean JA, Bachmann BO. Chem Biol. 2009;16:473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarker D, Pacey S, Workman P. Biomark Med. 2007;1:399–417. doi: 10.2217/17520363.1.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarker D, Workman P. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;96:213–268. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)96008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoelder S, Clarke PA, Workman P. Mol Oncol. 2012;6:155–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu P, Nielsen TE, Clausen MH. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:422–439. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross S, Rahal R, Stransky N, Lengauer C, Hoeflich KP. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1780–1789. doi: 10.1172/JCI76094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padmanabhan A, Li X, Bieberich CJ. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:14158–14169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.432377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toughiri R, Li X, Du Q, Bieberich CJ. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:823–830. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.