Significance

Intracellular membrane fusion is mediated by coupled folding and assembly of three or four soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins into a four-helix bundle. A rate-limiting step is the formation of a partial complex containing three helixes called the target (t)-SNARE complex on the target plasma membrane. The t-SNARE complex then serves as a template to guide stepwise zippering of the fourth helix, a process that is further regulated by other proteins. The synaptic t-SNARE complex readily misfolds. Consequently, its conformation, stability, and dynamics have not been well understood. Using optical tweezers and theoretical modeling, we elucidated the folding intermediates and kinetics of the t-SNARE complex and discovered a long-range conformational switch of t-SNAREs during SNARE zippering, which is essential for regulated SNARE assembly during synaptic vesicle fusion.

Keywords: t-SNARE complex, SNARE four-helix bundle, SNARE assembly, membrane fusion, optical tweezers

Abstract

Synaptic soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) couple their stepwise folding to fusion of synaptic vesicles with plasma membranes. In this process, three SNAREs assemble into a stable four-helix bundle. Arguably, the first and rate-limiting step of SNARE assembly is the formation of an activated binary target (t)-SNARE complex on the target plasma membrane, which then zippers with the vesicle (v)-SNARE on the vesicle to drive membrane fusion. However, the t-SNARE complex readily misfolds, and its structure, stability, and dynamics are elusive. Using single-molecule force spectroscopy, we modeled the synaptic t-SNARE complex as a parallel three-helix bundle with a small frayed C terminus. The helical bundle sequentially folded in an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD) separated by a central ionic layer, with total unfolding energy of ∼17 kBT, where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is 300 K. Peptide binding to the CTD activated the t-SNARE complex to initiate NTD zippering with the v-SNARE, a mechanism likely shared by the mammalian uncoordinated-18-1 protein (Munc18-1). The NTD zippering then dramatically stabilized the CTD, facilitating further SNARE zippering. The subtle bidirectional t-SNARE conformational switch was mediated by the ionic layer. Thus, the t-SNARE complex acted as a switch to enable fast and controlled SNARE zippering required for synaptic vesicle fusion and neurotransmission.

Synaptic soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) mediate fast and calcium-triggered fusion of synaptic vesicles to presynaptic plasma membranes required for neurotransmission (1). They consist of VAMP2 (vesicle associated membrane protein 2, also called synaptobrevin 2) anchored on vesicles (v-SNARE) and syntaxin and SNAP-25 (synaptosome associated protein 25) located on target plasma membranes (t-SNAREs) (2). These SNAREs contain characteristic SNARE motifs of ∼60 amino acids (3) (Fig. 1A). Syntaxin and SNAP-25 can form a 1:1 t-SNARE complex (4–6). During membrane fusion, the t- and v-SNAREs join to form an extraordinarily stable four-helix bundle (3, 7–10). In the core of the bundle are 15 layers of hydrophobic amino acids and a central ionic layer containing three glutamines and one arginine. Whereas the zippering energy and kinetics between t- and v-SNAREs have recently been measured (8, 9), the structure, stability, and dynamics of the t-SNARE complex have not been well understood.

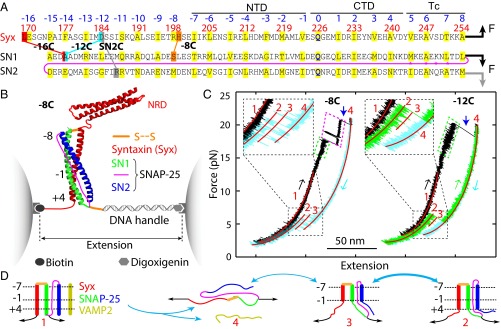

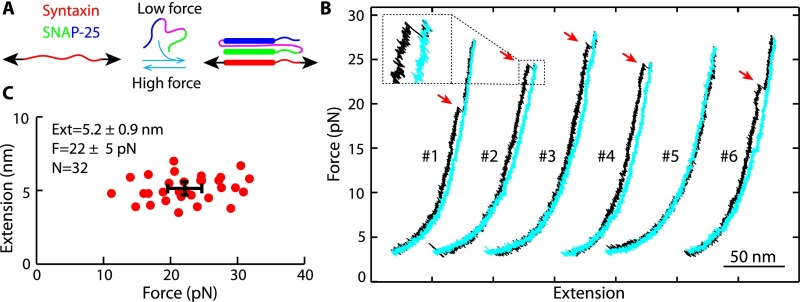

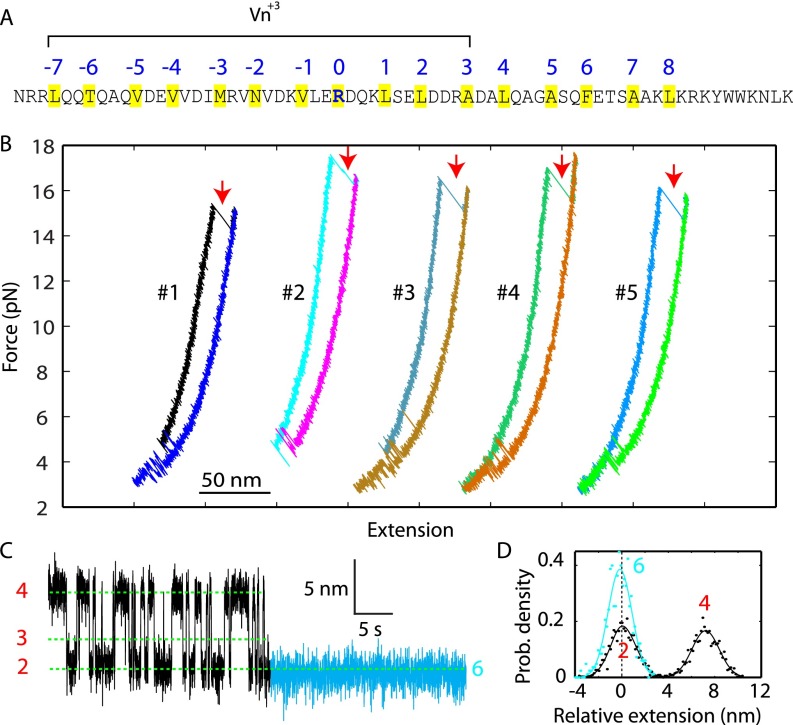

Fig. 1.

T-SNARE sequences, experimental setup, and derived folding states. (A) Amino acids of the synaptic syntaxin 1A (Syx) and SNAP-25B containing SNARE motifs. SNAP-25B consists of two SNARE motifs (SN1 and SN2) connected by a disordered linker (magenta line), with four intrinsic cysteines (marked by stars) mutated to serine. Amino acids of the hydrophobic and ionic layers in the SNARE motifs (numbered from −7 to +8) and their N-terminal extensions (numbered from −16 to −8) are highlighted in yellow. The syntaxin sequence is numbered in red. Four pairs of cross-linked amino acids are indicated by lines and labeled by their corresponding construct names and pulling sites (arrows). The t-SNARE complex contained three distinct folding domains: the NTD, the CTD, and the frayed Tc. (B) Experimental setup to pull a single t-SNARE complex (−8C) containing the NRD of syntaxin. The structure of the folded t-SNARE complex shown here was modeled based on the crystal structure of the SNARE ternary complex (3) and our single-molecule measurements. (C) FECs obtained by pulling (black and green) and relaxing (cyan) the two SNARE constructs −8C and −12C. The pulling or relaxing direction is indicated by arrows colored the same as the corresponding FECs. Blue arrows mark full disassembly of the ternary SNARE complex and accompanying dissociation of the VAMP2 molecule. Red lines are best fits of the corresponding FECs by the worm-like chain model. (D) Schematic of the SNARE transitions among four states, including the fully assembled ternary SNARE state 1, the folded t-SNARE state 2, the partially folded t-SNARE state 3, and the fully unfolded t-SNARE state 4.

The structure and dynamics of the t-SNARE complex are crucial for SNARE assembly and membrane fusion. Formation of the t-SNARE complex is likely an obligate intermediate before SNARE zippering (6, 11–14). A preformed t-SNARE complex docks the vesicles to plasma membranes (15) and boosts the speed, strength, and accuracy of SNARE zippering (5, 9, 16). Furthermore, the t-SNARE complex is an important target for proteins that regulate SNARE zippering and membrane fusion, such as Munc18-1, synaptotagmins, and complexin (8, 17–19). Finally, the t-SNARE complex shows intriguing dynamics in reconstituted membrane fusion. Peptides corresponding to the VAMP2 N-terminal domain (NTD; called Vn peptides or Vn) or C-terminal domain (CTD; called Vc) are often used to facilitate membrane fusion (6, 10, 20, 21). Tightly bound to the t-SNARE complex, they attenuate SNARE zippering (8, 22), yet surprisingly enhance the rate of membrane fusion (6, 10). The underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood, which calls for an improved understanding of the structure and dynamics of the t-SNARE complex.

Studying t-SNARE folding is challenging using ensemble-based experimental approaches, because the t-SNARE complex readily misfolds (6, 21, 23) and is highly dynamic (4). Syntaxin and SNAP-25 can efficiently form a stable parallel four-helix bundle containing two syntaxin molecules and one SNAP-25 molecule (the 2:1 complex), which inhibits SNARE zippering and membrane fusion (5, 6). In addition, it is reported that the t-SNARE complex folds into at least two alternative conformations in which either SNARE motif in SNAP-25 partially or completely dissociates from syntaxin (4). Interestingly, yeast t-SNARE homologs Sso1 and Sec9 do not misfold. Fiebig et al. (24) found that Sso1 in the t-SNARE complex is N-terminally structured but C-terminally disordered. Using optical tweezers, Ma et al. (8) and Gao et al. (9) observed that synaptic t-SNARE complexes unfold cooperatively at a high force when pulled from both ends of syntaxin, indicating a largely structured syntaxin in a stable t-SNARE complex. However, the detailed conformation of the t-SNARE complex, especially SNAP-25, and its stability and dynamics are not clear.

In this work, we measured the conformation, stability, and dynamics of a single synaptic t-SNARE complex using optical tweezers. Our single-molecule method prevented the t-SNARE complex from misfolding, thus allowing us to focus on the 1:1 complex. We found that the t-SNARE complex folded in two steps and had a frayed t-SNARE C terminus (Tc). Binding of Vn stabilized the CTD, whereas binding of Vc stabilized the NTD, structured the Tc, and promoted initial ternary SNARE zippering, potentially accounting for the positive effect of both peptides on membrane fusion.

Results

T-SNARE Constructs and Experimental Setup.

To measure the conformation and stability of the cytoplasmic t-SNARE complex, we first pulled a single t-SNARE complex at the C termini of syntaxin and the first SNARE motif in SNAP-25 (SN1) (Fig. 1 A and B). Their N termini were cross-linked by a disulfide bond formed between two cysteine residues. We chose the N-terminal cross-linking site such that it facilitated refolding of the t-SNARE complex but minimally altered its structure. We tested three cross-linking sites by substituting the corresponding amino acids with cysteine and designated the SNARE constructs as −8C, −12C, and −16C (Fig. 1A). To prevent t-SNARE misfolding and ensure correct cross-linking, we first formed the ternary SNARE complex and then removed the VAMP2 molecule by unfolding the ternary complex. The complex was attached on one end to a streptavidin-coated polystyrene bead through a biotinylated Avi-tag and on the other end to an antidigoxigenin antibody-coated polystyrene bead through a 2,260-bp DNA handle (9) (Fig. 1B). The beads were trapped in two optical traps formed by focused laser beams. By moving one optical trap relative to the other, we controlled the force applied on the SNARE complex and measured the end-to-end extension of the SNARE/DNA tether in response to the force. We recorded the force and extension at 10 kHz and used them to derive t-SNARE folding and stability.

Syntaxin and SN1 Are Largely Structured and Fold Reversibly.

We first pulled a single ternary SNARE construct −8C to a force of ∼22 pN, leading to a representative force-extension curve (FEC) shown in Fig. 1C. Below ∼15 pN, the extension increased monotonically with force, mainly due to stretching of the semiflexible DNA handle. As a result, the FEC could be fit by a worm-like chain model (25) (Fig. 1C, red curve). Above 17 pN, first fast and then slow extension flickering (Fig. 1C, regions marked by green and magenta parallelograms, respectively) appeared successively as force increased, indicating reversible folding and unfolding transitions of a SNARE C-terminal region and middle region, respectively. At ∼20 pN, an abrupt extension jump (Fig. 1C, indicated by a blue arrow) represented irreversible unfolding of the remaining N-terminal region. Pulling the molecule to above 20 pN did not cause any additional unfolding, which demonstrated that the SNARE complex had been fully unfolded (Fig. 1C, state 4). The above interpretations on SNARE transitions were confirmed by the similarities and differences in the FECs obtained by pulling the other two SNARE constructs −12C and −16C (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1).

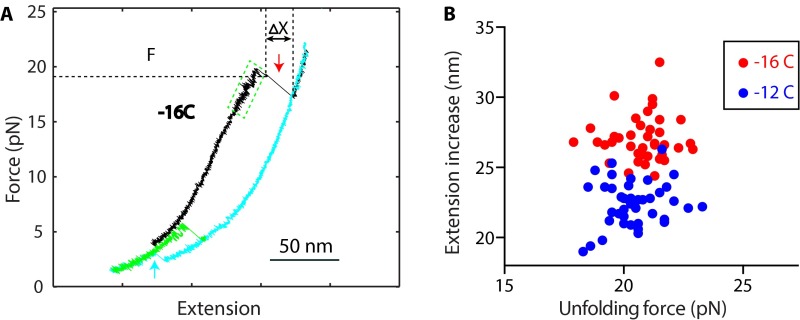

Fig. S1.

Comparison of t-SNARE folding and unfolding properties in different SNARE constructs. (A) FECs of the SNARE construct −16C. A single t-SNARE complex was first pulled to disassemble the ternary SNARE complex (black), leading to dissociation of the VAMP2 molecule (red arrow); then relaxed to a low force to detect t-SNARE refolding (cyan arrow); and finally pulled again to see t-SNARE unfolding (green). The green dashed rectangle marks the reversible folding and unfolding transition of the C-terminal region in the ternary SNARE complex. The force and extension increase (ΔX) associated with unfolding of the N-terminal region in the ternary complex are indicated. Compared with the three SNARE constructs −8C, −12C, and −16C, the FECs obtained by pulling the ternary SNARE complex are similar, especially between −12C and −16C. The construct −8C shows a unique slow MD transition (Fig. 1C), probably caused by the N-terminal cross-linking that decreases the stability of the MD. However, in all three SNARE constructs, N-terminal cross-linking did not significantly change t-SNARE folding energy and conformations of the intermediate state 3 and the folded state 2 (Table 1). (B) Comparison of the distributions of the force and extension increase associated with unfolding of the NTD of the ternary SNARE complexes in constructs −12C (Fig. 1C) and −16C. The unfolding was accompanied by complete unfolding of the t-SNARE complex and dissociation of the VAMP2 molecule. Each dot represents unfolding of one of 40 ternary SNARE complexes. An N-terminal shift of the cross-linking site between syntaxin and SNAP-25 did not significantly change the unfolding force distribution, but shifted the extension distribution to higher extension. The observations confirm that the irreversible extension jumps seen in the FECs (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A) were caused by unfolding of the SNARE NTD.

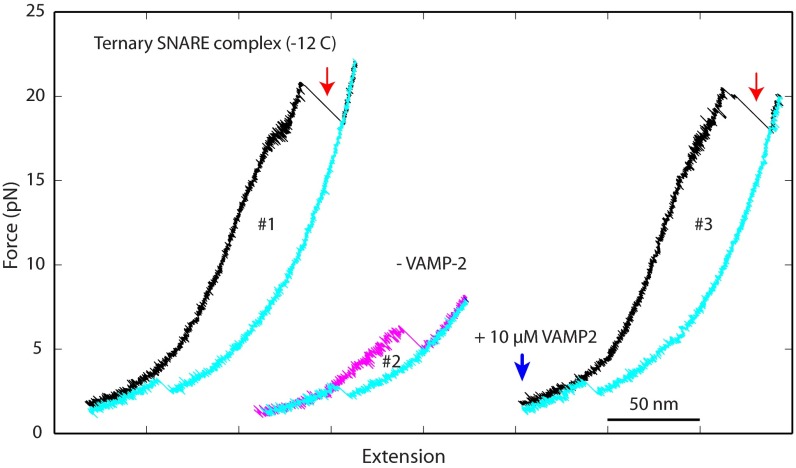

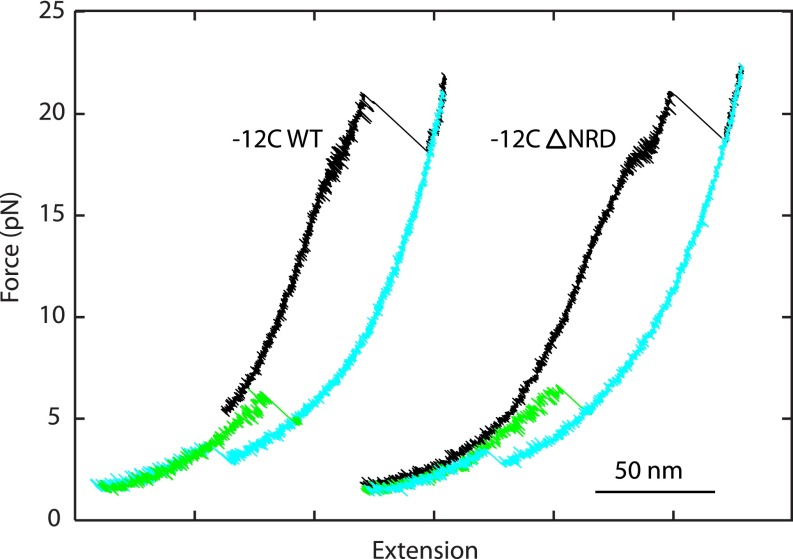

Upon relaxation, the SNARE complex in all three constructs remained unfolded at a force above ∼7 pN, but refolded below this force (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). The folding process was reversible via a transient intermediate state (Fig. 1 C and D, state 3). Interestingly, the fully refolded SNARE complex (in state 2) had an extension greater than the fully assembled ternary SNARE complex (in state 2), suggesting a partially folded t-SNARE complex. Pulling the t-SNAREs again revealed an FEC that overlapped the relaxation FEC (Fig. 1C, compare the green and cyan FECs for −12C). These observations indicate that the VAMP2 molecule dissociated from the t-SNAREs upon disassembly of the ternary complex. To confirm this interpretation, we added 10 μM VAMP2 into the solution after a single ternary SNARE complex had been disassembled and found that VAMP2 restored assembly of the ternary SNARE complex (Fig. S2). Thus, disassembly of the ternary SNARE complex led to dissociation of the VAMP2 molecule (Fig. 1D, states 1–4) and generated an unfolded t-SNARE complex that partially refolded at a low force via an intermediate state 3. In addition, the intermediate state 3 appeared to be partially zippered (Fig. 1D), because shifting the N-terminal cross-linking site away from the SNARE motifs (from −8C to −12C to −16C) changed the extension of the intermediate state relative to the extension of the unfolded t-SNARE state, but not of the folded t-SNARE state (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). Finally, we found that the N-terminal regulatory domain (NRD) of syntaxin (Fig. 1B) did not significantly affect t-SNARE folding, because the t-SNARE complex without the NRD showed an FEC identical to the FEC of the complex with the NRD (Fig. S3). This finding indicates that the NRD did not strongly interact with the SNARE motifs, consistent with our previous observation (8).

Fig. S2.

Single t-SNARE complex is generated by fully disassembling the ternary SNARE complex to dissociate the VAMP2 molecule. A t-SNARE complex in the construct −12C was consecutively pulled (black and magenta) and relaxed (cyan) for three rounds (#1–#3), with the corresponding FECs shown. The t-SNARE was first pulled in the preassembled ternary complex (#1, black), which was disassembled at ∼22 pN with dissociation of the VAMP2 molecule (marked by a red arrow). Then, the free t-SNARE complex was relaxed and folded at ∼3 pN (#1, cyan). The t-SNARE folding was confirmed by the second round of pulling and relaxation (#2), which showed typical t-SNARE unfolding and refolding signatures. We then added 10 μM VAMP2 into the solution and waited for ∼30 s to allow VAMP2 to bind the t-SNARE complex. Finally, the t-SNARE complex was pulled again, revealing unfolding signatures characteristic of the ternary SNARE complex (#3, black). This finding confirmed that the VAMP2 molecule bound to the t-SNARE complex to form the ternary SNARE complex. Relaxing the t-SNARE complex after disassembling the ternary complex again showed the typical t-SNARE refolding event (#3, cyan). For clarity, FECs in pulling rounds #2 and #3 were shifted toward higher extensions.

Fig. S3.

FECs of the SNARE complex (−12C) with (Right) or without (Left) the NRD of syntaxin. The FECs of the complexes correspond to the pulling cycle of the ternary SNARE complex (black) and the subsequent relaxation cycle of the syntaxin–SNAP-25 conjugate (cyan). After a t-SNARE complex reassembled, it was pulled again for another round to see its unfolding (green).

Structure, Stability, and Folding Dynamics of the T-SNARE Complex.

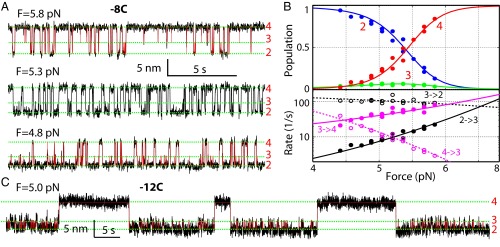

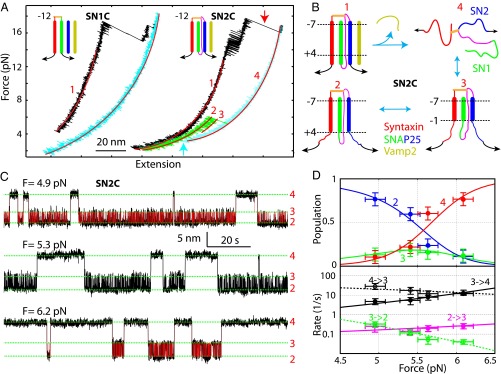

To characterize t-SNARE folding at greater spatiotemporal resolution, we held the complex at constant mean forces in the range of 4–6 pN and detected its extension flickering caused by spontaneous t-SNARE transitions. Fig. 2A shows three representative extension trajectories for construct −8C. We found that the t-SNARE complex folded and unfolded among states 2, 3, and 4 with distinct average extensions. We analyzed the extension trajectories using three-state hidden-Markov modeling (HMM) (8, 26, 27), which revealed idealized extension transitions (Fig. 2A) and best-fit model parameters, including state probabilities and transition rates (Fig. 2B). The intermediate state 3 had a population of <7% and a dwell time of 4–8 ms over the force range tested (Fig. S4). As force increased, the probabilities of the folded state 2 and the unfolded state 4 decreased and increased, respectively, and the probability of the intermediate state 3 first increased and then decreased (Fig. 2B, Top). The observation suggests that the intermediate state 3 was on-pathway for t-SNARE folding and unfolding. Indeed, the HMM shows that the rates of sequential transitions between states 4 and 3 and between states 3 and 2 were 20- to 1,000-fold greater than the rate of direct transition between states 2 and 4. Accordingly, we ignored the nonsequential transitions in our subsequent analyses (Fig. 2B, Bottom). To confirm the t-SNARE transitions further, we repeated the experiment using construct −12C (Fig. 2C). The larger loop introduced by cross-linking (Fig. 1A) dramatically slowed down the transition between states 3 and 4 (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4), as is observed in many other systems (28). Consequently, the intermediate state 3 was better resolved due to its greater lifetime (Fig. 2C). These findings confirm that the transition between states 3 and 4 was caused by the t-SNARE NTD (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the transition between states 3 and 2 was barely affected by the change in the cross-linking site, which corroborates the partially zippered intermediate state 3.

Fig. 2.

Energetics and kinetics of three-state folding of the t-SNARE complex. (A) Extension-time trajectories show reversible transitions of the t-SNARE complex (−8C) at the indicated constant mean force F. Red lines are idealized trajectories determined by HMM, and green dashed lines mark the corresponding state positions. (B) Force-dependent probabilities of three t-SNARE folding states (Top) and their associated transition rates (Bottom). Experimental measurements (symbols) were fit by a theoretical model (solid lines; Materials and Methods). (C) Extension-time trajectories of the t-SNARE complex (−12C). Idealized trajectories derived from HMM are shown as red lines.

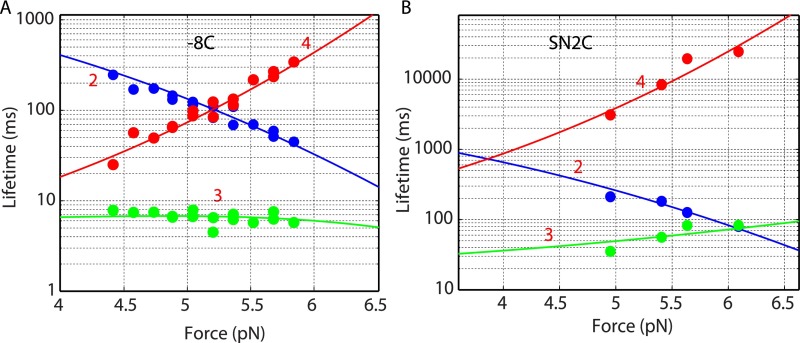

Fig. S4.

Force-dependent lifetimes of different folding states of the t-SNARE complexes −8C (A) and SN2C (B). The experimental measurements (symbols) were fit by a theoretical model (lines) (Materials and Methods). The lifetime of each state is the inverse of the sum of the rate constants for all transitions that leave the state. For example, the lifetime of the intermediate state 3 () was calculated as , where and are the rate constants of the t-SNARE complex changing from the intermediate state 3 to the folded state 2 and to state 4, respectively (Fig. 1D). Whereas is independent of the cross-linking site, decreases as the cross-linking site is shifted to the N terminus in the presence of force. Thus, the lifetime of the intermediate state 3 in construct SN2C or −12C (Fig. 2C) is greater than in construct −8C.

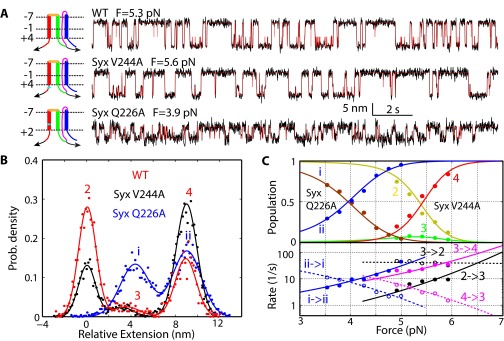

To derive the conformations and folding energies of the partially zippered state and the folded state, we simultaneously fit the measured state populations, transition rates, forces, and extension changes using a theoretical model (26). The model treated the conformations and energies of different folding states at zero force as fitting parameters and accounted for all of the experimental measurements under tension (Fig. 2B). We assumed that the three SNARE motifs synchronously zippered from the −7 layer toward the +8 layer, using the t-SNARE structure in the ternary complex as a template (3) (Materials and Methods). This assumption was tested by a series of experiments to be described below. Based on this inferred folding pathway, the positions of the partially zippered state 3 and the folded state 2 were mainly determined by their extensions relative to the extension of the unfolded state 4. The model fitting showed that the folded t-SNARE complex was largely a three-helix bundle with frayed C termini for both syntaxin and SN1. The boundary between the ordered and disordered regions lay approximately between the +4 and +5 layers (Fig. 1A and Table 1). In the partially zippered state 3, the boundary was shifted to approximately −1 layer. Thus, the t-SNARE complex folded in two steps, first in the NTD (from −7 layer to −1 layer) and then in the CTD (from 0 layer to +4 layer). The model fitting also revealed unfolding energies of 5 kBT (Boltzmann constant times temperature) for the NTD and 7 kBT for the CTD. A small barrier of 4 (±2) kBT for CTD folding suggests a lifetime range of 7–400 μs for the intermediate state 3 at zero force. We derived a simple theory to relate the unimolecular NTD folding detected by us to bimolecular association between syntaxin and SNAP-25 (Supporting Information, Fig. S5, and Table S1). The theory yielded a binding energy of 17 kBT or a dissociation constant of 41 nM and an apparent binding rate constant of 1.0 × 104 M−1⋅s−1 between syntaxin and SNAP-25 (Table 1 and Table S1). The binding affinity and rate are consistent with previous measurements of 16 nM and 0.6 × 104 M−1⋅s−1, respectively (5, 6). Our structural model for t-SNARE folding was confirmed by effects of single alanine substitutions in syntaxin, one at the ionic layer in the folded region (Syx Q226A) and the other at the +5 layer in the disordered region (Syx V244A). As was predicted by the model, the former dramatically destabilized the t-SNARE complex and the latter barely changed t-SNARE folding (Table 1 and Fig. S6). This finding also shows that the ionic layer plays an important role in stabilizing the t-SNARE complex. Finally, our model was further verified by pulling the t-SNARE complex from the N and C termini of syntaxin (Fig. S7) and the results below.

Table 1.

Domains and energies associated with t-SNARE folding

| SNARE construct | CTD | NTD | Total dissociation energy, kBT | ||

| Position, aa | Unfolding energy, kBT | Position, aa | Unfolding energy, kBT | ||

| −8C | 243 (2) | 7 (4) | 222 (1) | 5 (1) | 17 (4) |

| Syx Q226A | NA | NA | 233 (5) | 6 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Syx V244A | 243 (5) | 7 (4) | 223 (3) | 5 (2) | 17 (4) |

| SN2C | 243 (7) | 6 (3) | 222 (4) | 6 (1) | 18 (3) |

The C-terminal border of the CTD or NTD is shown by the number of the corresponding amino acid (aa) in syntaxin (Fig. 1A). The total dissociation energy in the last column was calculated as the sum of the CTD energy, the NTD energy, and the correction for the latter due to N-terminal cross-linking (Supporting Information and Table S1). Shown in parentheses is the SD. The CTD of Syx Q226A is largely disordered (Fig. S6), and thus not accessed (NA).

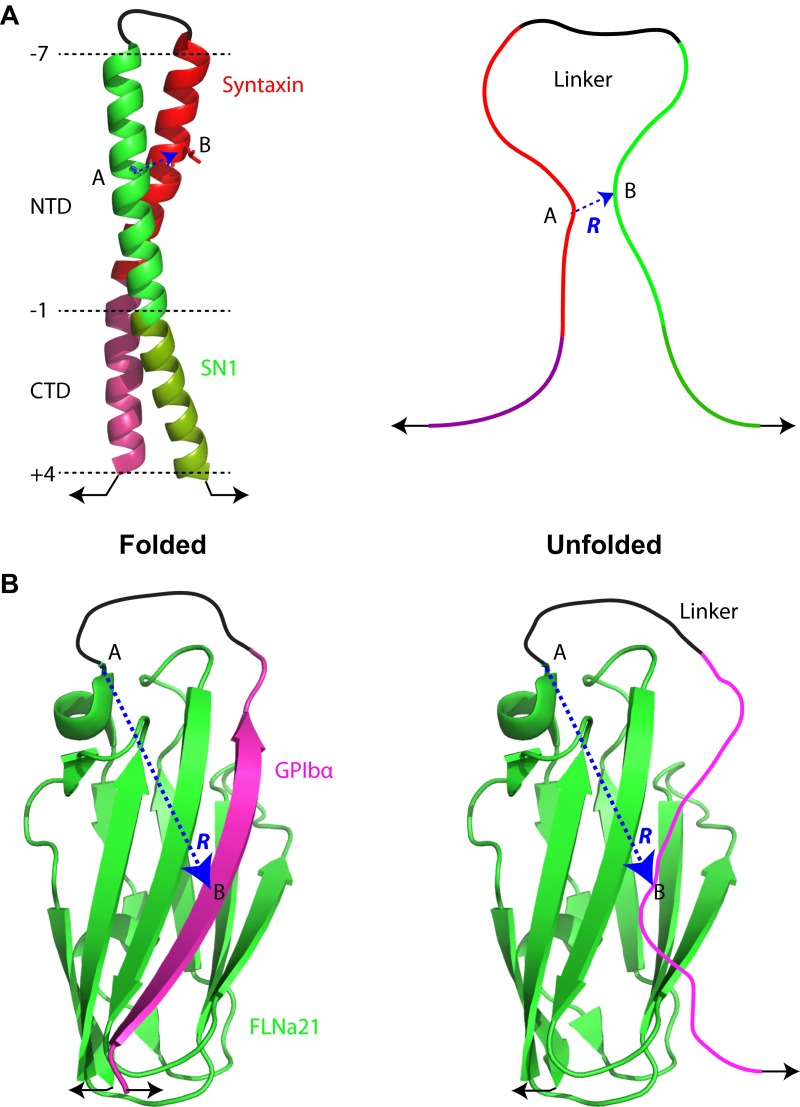

Fig. S5.

Determination of the linker and its end-to-end distance to calculate the effective concentration of the tethered proteins. (A) T-SNARE complex in the construct −8C. (Left) For clarity, the SN2 helix is omitted in the structure of the folded t-SNARE complex. The structure is modeled based on the crystal structure of the ternary SNARE complex (3) and our single-molecule measurements. (B) GPIbα–FLNa21 complex (37, 40). In both A and B, the structures show the cross-linked protein complexes in the folded and bound states (Left), and the structures model the conformations of the unbound proteins that are ready to rebind (Right). The effective concentration of the tethered SN1 or GPIbα is the local concentration of the middle amino acid of SN1 NTD or GPIBα at the same position as in the corresponding complex (position B) while anchored to the partner proteins (at position A) via the disordered polypeptide linker between the two positions. The dashed blue line indicates the end-to-end distance of the linker. The black arrows denote the pulling sites.

Table S1.

Comparison of the linker contour length (L), end-to-end distance (R), effective concentration, and energy correction

| Protein | L, aa | R, nm | Effective concentration,* mM | Measured concentration,† mM | Predicted energy correction,‡ kBT | Measured energy correction, kBT |

| GCN4 coiled-coil | 39 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 4 | 5.1 | 2.7 (0.7)§, 4.8 (0.7)¶ |

| GPIbα–FLNa21 complex | 19 | 2.0 | 11 | 9 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| −8C | 28 | 1.5 | 9.7 | 17 | 4.6 | |

| Syx Q226A | 39 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 5.1 | ||

| Syx V244A | 29 | 1.5 | 9.3 | 4.7 | ||

| −12C | 64 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 5.7 | ||

| −16C | 79 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 6.0 | ||

| SN2C | 54 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 |

Fig. S6.

Ionic layer stabilizes the t-SNARE complex, especially the CTD. (A) Extension-time trajectories of the WT t-SNARE complex (−8C) and two mutants. Both mutants contained single alanine substitutions in syntaxin in the construct −8C, one at the ionic layer and the other at the +5 layer, with the corresponding t-SNARE complexes designated as Syx Q226A and Syx V244A, respectively. The idealized trajectories (red) were determined by HMM. (Left) Conformations of the folded t-SNARE complex are depicted, in which the black arrows and cyan bars indicate the pulling direction and the point mutations, respectively. (B) Probability (Prob.) density distributions of the extensions shown in A (symbols) and their best fits by a sum of three or two Gaussian functions (lines). Note that Syx Q226A decreased both the extension change and the equilibrium force accompanying the t-SNARE transition. Moreover, the transition became two-state. (C) Force-dependent state probabilities (Top) and transition rates (Bottom) of the mutant t-SNARE complexes Syx Q226A (states labeled as i and ii) and Syx V244A (states 2–4). Results of model fitting are shown by lines, yielding the best-fit conformations exhibited in A and energies listed in Table 1.

Fig. S7.

The 1:1 t-SNARE complex mainly folds into a single conformation. (A) Schematics of the method to study t-SNARE folding by pulling the t-SNARE complex from the N and C termini of syntaxin. This pulling direction removed the constraint on t-SNARE folding due to the N-terminal cross-linking between syntaxin and SNAP-25 used in other pulling directions (Fig. 1). (B) FECs obtained by consecutively pulling (black) and relaxing (cyan) a single syntaxin molecule in the presence of 20 μM SNAP-25. The extension jumps indicated by red arrows were caused by t-SNARE unfolding. In this experiment, we first held the syntaxin molecule at a low force (<3 pN) for ∼30 s to allow SNAP-25 to bind and then pulled to unfold the resultant t-SNARE complex to detect its conformation. Finally, the unfolded syntaxin was relaxed and the above process was repeated. (C) Distribution of the forces and extension increases associated with 32 t-SNARE unfolding events, with their averages and SDs (also indicated by the error bars) shown. The average force and extension change of t-SNARE unfolding are equal to the corresponding measurements for the correctly folded t-SNARE complexes in this pulling direction, which were prepared by unzipping ternary SNARE complexes (9). In addition, the extension change is consistent with the helix-to-coil transition of the syntaxin molecule upon t-SNARE unfolding.

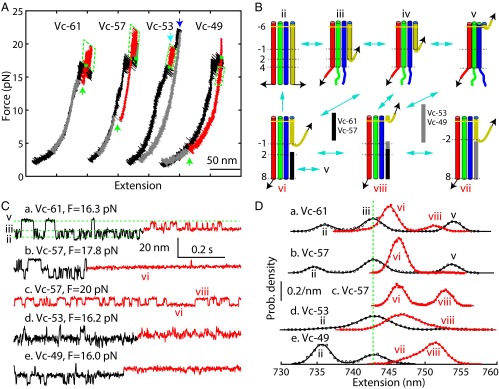

Three SNARE Motifs Fold Synchronously.

It was unclear what role the C-terminal SNARE motif of SNAP-25 (SN2) played in the t-SNARE folding. To examine the impact of SN2, we split SNAP-25 in construct −12C into SN1 and SN2 and designated the quaternary SNARE construct as SN1C (Fig. 3A). Full disassembly of the complex led to dissociation of both VAMP2 and SN2, generating a syntaxin-SN1 conjugate. Relaxing the conjugate down to around zero force, we did not observe any folding event (Fig. 3A, cyan FEC). This finding demonstrated that SN2 was essential for t-SNARE folding and that syntaxin and SN1 could not form any stable structure. The t-SNARE structure derived by us contrasts with the previous t-SNARE structures in which SN2 can partially or completely dissociate (4, 29). Note that syntaxin and SN1 can associate into a four-helix bundle with two copies of each (16, 30), which cannot form under our experimental conditions. To examine the SN2 conformation in the t-SNARE complex further, we made a t-SNARE construct designated as SN2C, in which the N terminus of SN2 was cross-linked to syntaxin at the −12 layer (Figs. 1A and 3A). We now pulled the t-SNARE complex from the C termini of SN2 and syntaxin and obtained representative FECs shown in Fig. 3A. After unfolding the ternary SNARE complex (Fig. 3A, red arrow), we relaxed the remaining t-SNAREs and saw their cooperative folding at ∼3 pN (Fig. 3A, cyan arrow). The folded t-SNARE complex (in state 2) again had an extension greater than the corresponding ternary complex, confirming a frayed SN2 in Tc (Fig. 3B). Similar to −12C, further pulling the refolded SN2C caused a reversible transition between states 2 and 3 in the force range of 4–6 pN (Fig. 3A, green FEC). We then held the t-SNARE complex at constant mean forces and detected its force-dependent three-state transitions (Fig. 3C). Like −12C, the construct that we created exhibited a slow NTD transition and a fast CTD transition. Detailed analysis (Fig. 3D) showed that the conformations and unfolding energies of the t-SNARE complex derived from pulling SN2 are close to the corresponding measurements obtained from pulling SN1 (Table 1). These comparisons revealed that the three SNARE motifs in the t-SNARE complex zippered synchronously in two steps, first in NTD and then in CTD, and were all frayed in Tc (Fig. 1D). Compared with the half-zippered or highly dynamic t-SNARE structures previously reported (4, 10), the t-SNARE structure deduced by us is significantly more ordered and stable.

Fig. 3.

Three t-SNARE helices fold synchronously. (A) FECs obtained by first pulling (black) and then relaxing (cyan) the t-SNARE constructs SN1C and SN2C. Further pulling SN2C led to the FEC shown in green. FEC regions were fit by the worm-like chain model (red lines), revealing different SNARE folding states (red numbers). (B) Schematic of the states and their transitions for SN2C. (C) Extension-time trajectories of SN2C at constant mean forces. The idealized extension transitions (red lines) were determined by three-state HMM, and the average state extensions are marked by green dashed lines. (D) Force-dependent probabilities (Top) and transition rates (Bottom) associated with the different folding states of the t-SNARE complex SN2C. Results of model fitting are shown in solid lines. Error bars indicate SDs.

Vc Binding Stabilizes the Frayed Tc.

To examine effects of Vc peptides on t-SNARE folding and ternary SNARE zippering, we tested four Vc peptides that start at different positions in the VAMP2 sequence but end at the same amino acid 96 (Fig. 4A). These peptides are designated by “Vc-” followed by their starting amino acid numbers. We first pulled the t-SNARE constructs −8C and SN2C in the presence of 10 μM Vc-61 (10). After unfolding the ternary SNARE complexes (Fig. 4B, black FECs), we first refolded the t-SNARE complexes at a low force (Fig. 4B, gray FECs) and then added Vc-61 into the solution to allow Vc-61 to bind to the t-SNARE complexes (Fig. 4B, black arrows). In subsequent pulling, the Vc-bound t-SNARE complexes showed extensions identical to the ternary SNARE complex (Fig. 4B, compare red FECs with black FECs), indicating that Vc binding induced Tc folding as in the ternary complex (Fig. 4C, state 5). The Vc-bound t-SNARE complex completely unfolded at ∼10 pN (Fig. 4B, red arrows), which suggests that Vc significantly enhanced the mechanical stability of the t-SNARE complex.

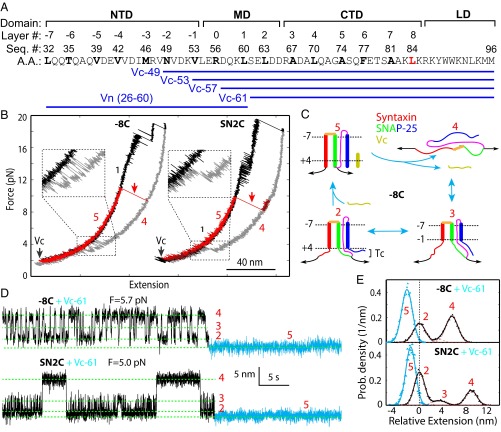

Fig. 4.

Vc peptides induce Tc folding. (A) VAMP2, Vc, and Vn sequences and ternary SNARE zippering domains, including the MD and linker domain (LD). (B) FECs of the t-SNARE complexes −8C and SN2C in the absence and presence of Vc. We first pulled to disassemble a ternary SNARE complex (black), and then relaxed the t-SNARE complex (gray), added Vc (black arrows), and finally unfolded the Vc-bound t-SNARE complex (red FECs and arrows). (C) Schematic model of Vc-induced Tc folding in −8C. (D) Extension-time trajectories of the t-SNARE complexes −8C (Top) and SN2C (Bottom) at the indicated forces in the presence 0.5 μM Vc. The Vc-bound regions are highlighted in cyan. (E) Probability density distributions of the extensions in C (symbols with corresponding colors) and their best fits by one Gaussian function or a sum of three Gaussian functions (lines). For the latter, individual Gaussian functions were plotted in red dashed lines.

To observe the Vc-induced disorder-to-helix transition in Tc further, we held the t-SNARE complex at a constant mean force in the presence of 0.5 μM Vc-61. For both constructs −8C and SN2C, we first observed reversible three-state transitions characteristic of the free t-SNARE complex (Fig. 4D, black regions). Then, the transitions stopped at a low extension, consistent with the Vc-bound t-SNARE state (Fig. 4D, cyan regions). The t-SNARE complex remained in the Vc-bound state for more than 20 min, corroborating a strong association between Vc and the t-SNARE complex. The Vc-bound state 5 in both −8C and SN2C had an extension that was 2–4 nm lower than the extension of the folded t-SNARE complex in state 2, with an average of 2.6 (±0.4) nm (Fig. 4 D and E). The extension change is consistent with folding of the whole Tc, which extends our previous observation on the Vc-induced folding in the frayed syntaxin C terminus (8).

Vn Binding Stabilizes the CTD, but Not Tc.

Li et al. (10) recently demonstrated that the t-SNARE complex prebound by Vn also greatly promotes SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. To pinpoint its underlying mechanism, we investigated the effect of Vn on t-SNARE folding (Fig. 4A). In the presence of 10 μM Vn, the t-SNARE complex initially showed the same extension as the folded t-SNARE state 2 at a low force (Fig. 5A, compare cyan and gray FECs), indicating that Vn bound to the t-SNARE complex but did not induce Tc folding (Fig. 5B, state 6). However, unlike the free t-SNARE complex, the Vn-bound t-SNARE complex remained in the folded state to a high force, typically around 13 pN. Then, the complex abruptly and completely unfolded (Figs. 5A, cyan arrows and 5B, states 6 to 4). The unfolding force of the Vn-bound t-SNARE complex approximately followed a Gaussian distribution (Fig. 5C, Top). The average unfolding force of 13.4 (±1.6) pN was significantly higher than the average equilibrium unfolding force of the t-SNARE complex alone, or ∼5.4 pN (Fig. 2B). These observations indicate that Vn greatly stabilized the t-SNARE CTD. To confirm this finding, we examined Vn binding at a constant mean force. For both −8C and SN2C, Vn binding trapped the t-SNARE complex in a low extension state (Fig. 5D, cyan regions). A comparison of the extension probability density distributions of the Vn-bound and -unbound states showed that the Vn-bound t-SNARE state 6 had an extension identical to the folded t-SNARE state 2 (Fig. 5E). The finding confirms that Vn stabilized CTD, but not Tc (Fig. 5B). Moreover, lengthening the Vn peptide to the +3 layer led to the same conclusion (Fig. S8), indicating a common role of Vn peptides in specifically stabilizing the CTD. Finally, the Vn-induced CTD stabilization is further supported by our experiments in the presence of both Vn and Vc peptides (Fig. 5 A–C). Interestingly, Tc unfolding was enough to dissociate Vc (Fig. 5B, states 7 to 6). As a result, the distribution of the force to dissociate Vc did not significantly depend on Vn (Fig. 5C, compare Middle and Bottom). Therefore, a structured Tc is required for SNARE CTD zippering. In conclusion, our results suggest that Vn binding significantly stabilized the CTD, but did not induce CTD folding, in contrast to a recent derivation (10).

Fig. 5.

Vn peptide stabilizes the CTD, but not Tc. (A) FECs obtained by pulling the t-SNARE complexes −8C and SN2C in the ternary SNARE complexes (black) in the presence of Vn (cyan) or in the presence of both Vn and Vc (red). Events of Vn dissociation, Vc dissociation, and t-SNARE refolding are indicated by cyan, red, and gray arrows, respectively. (B) Schematic model illustrates the states and transitions of the t-SNARE complex −8C in the presence of both Vn and Vc. (C) Histogram distribution of the unfolding force of the t-SNARE complex bound by Vn (Top), both Vn and Vc (Middle), or Vc only (Bottom). In the presence of both Vn and Vc, the unfolding force is associated with the first unfolding event corresponding to Vc dissociation. (D) Extension-time trajectories of the t-SNARE complexes −8C and SN2C at constant mean forces F in 0.5 μM Vn. The Vn-bound states are highlighted in cyan. (E) Probability density distributions of the extension regions in black and cyan in C (symbols) and their best fits by Gaussian functions (lines).

Fig. S8.

Vn peptide stabilizes t-SNARE CTD, but not Tc. (A) Amino acid sequences of the SNARE motif in VAMP2 and the Vn peptide (Vn+3). The hydrophobic and ionic layers are highlighted in yellow and labeled by their layer numbers. (B) FECs obtained by pulling and then relaxing a single t-SNARE complex for five rounds (#1–#5) in the presence of 10μM Vn+3. Unfolding of the Vn-bound t-SNARE complex is marked by red arrows. The average unfolding force became greater when this longer Vn peptide was used, compared with the short Vn version (Fig. 5C, Top). (C) Extension-time trajectory of the t-SNARE complex under a constant mean force of 5.0 pN. The Vn-bound region is colored in cyan. (D) Probability density distributions of the corresponding extension regions in C.

Effect of T-SNARE Conformational Switch on Ternary SNARE Zippering.

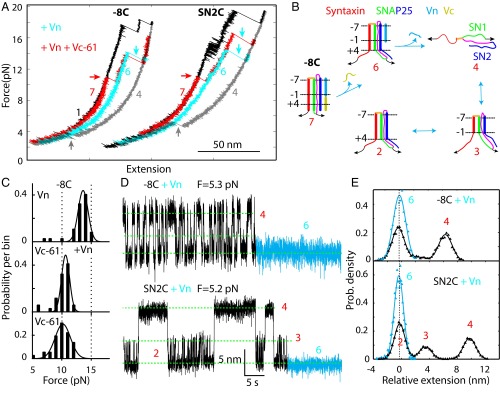

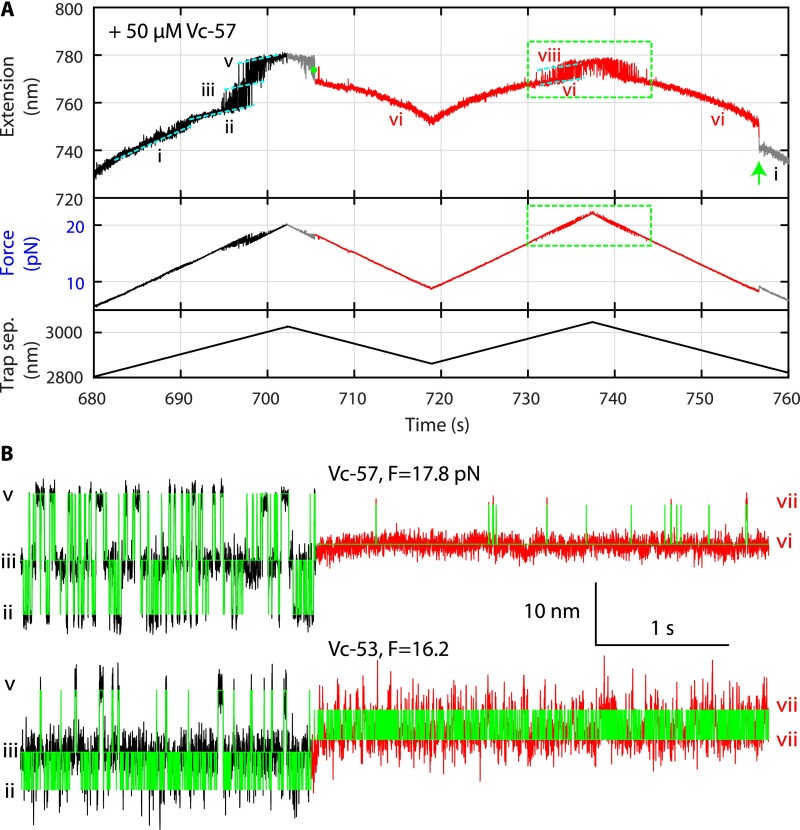

We have recently shown that the t- and v-SNAREs zipper stepwise in three distinct domains, the NTD, the middle domain (MD), and the CTD (8) (Fig. 4A), in a manner similar to stepwise t-SNARE folding reported here. In particular, the NTDs of both the ternary SNARE complex and the t-SNARE complex correspond to the same hydrophobic layers from −7 to −1. Our above Vn-binding experiment suggests that as VAMP2 zippers to MD, the t-SNARE CTD is stabilized and forms a rigid template for the v-SNARE to zipper, thereby promoting the speed and energy of SNARE zippering. This observation partly explains why Vn peptides enhance membrane fusion (10). However, it remains unclear how Vc peptides stimulate membrane fusion (6, 20), given their role in attenuating v-SNARE zippering (8). To pinpoint the effect of Vc peptides on SNARE zippering further, we repeated our SNARE zippering assay (8) in the presence of four Vc peptides with different lengths (Figs. 4A and 6A). Here, a ternary SNARE complex was cross-linked between syntaxin and VAMP2 near their −6 layers and pulled from their C termini in the presence of 50 μM Vc peptides (Fig. 6B). The FECs showed the folding states and pathways of the SNARE complex alone as previously reported (Fig. 6A and Fig. S9A, black and gray curves, and Fig. 6B, states ii–v) (8). However, the FECs also contained new features from the Vc-bound SNARE complexes (Fig. 6A and Fig. S9A, red curves). Vc binding occurred in the force range of the overlapping CTD, MD, and NTD transitions (Fig. 6A, green dots), which suggests that Vc bound to the t-SNARE complex after VAMP2 was partially or completely unzipped or destabilized by force (Fig. 6B). The bound Vc was generally displaced at a low force, as was manifested by an extension drop during relaxation (Fig. 6A, green arrows, and Fig. 6B, from state vi or vii to state ii). The Vc displacing force was stochastic and dependent on the length of the Vc peptide, with a smaller average displacing force for a longer Vc peptide (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Vc peptides enhance SNARE NTD association. (A) FECs obtained by pulling (black) and relaxing (gray) single ternary SNARE complexes in the presence of different Vc peptides. The Vc-bound SNARE states are shown in red as in C and D, with the NTD transitions marked by green dashed parallelograms. Vc peptides bound to SNARE complexes at green points and were displaced at points near green arrows. As a rare event, Vc-53 dissociated from the SNARE complex at a high force (marked by cyan arrows), followed by t-SNARE unfolding (blue arrow). The time-dependent force and extension corresponding to the FECs with Vc-57 are shown in Fig. S9A. (B) Diagram of different states and transitions involved in SNARE zippering and Vc binding, including the activated t-SNARE state viii. (C) Extension-time trajectories showing Vc binding at the indicated constant mean forces. Green dashed lines indicate the positions of different states shown in B. Extended views of two trajectories here are shown in Fig. S9B. (D) Probability density distributions of the extensions shown in C corresponding to the Vc-unbound states (black) and the Vc-bound states (red).

Fig. S9.

Vc peptides enhanced the rate of initial SNARE zippering and altered the stability of the ternary SNARE NTD. (A) Time-dependent extension, instantaneous force, and trap separation (sep.) corresponding to the FECs of the ternary SNARE complex in the presence of Vc-57 shown in Fig. 6A. Different SNARE folding states are indicated as in Fig. 6B, and the corresponding curves are colored as in Fig. 6A. The additional state i represents the fully assembled ternary SNARE complex, whereas state ii denotes the folded four-helix bundle with the linker domain unfolded (8). The intermediate state iv has a typical lifetime less than 1 ms, and thus is only clearly seen in some extension trajectories. The trap separation controlled the pulling and relaxation of the ternary SNARE complex. (B) Extended views of the extension-time trajectories shown in Fig. 6A (traces b and d) and their idealized transitions (green lines) derived by HMM. The HMM revealed the NTD folding rates in the absence and presence of Vc peptides shown in Table 2. Data in A and Fig. 6A were mean-filtered using a 5-ms time window, whereas data in B and Fig. 6C were filtered using a 1-ms time window.

Vc binding dramatically changed the energetics of ternary SNARE zippering. Because Vc binding blocked CTD and MD folding, the CTD and MD transitions were inhibited and only the two-state NTD transition remained (Fig. 6C and Fig. S9B). Vc binding changed the NTD stability in a length-dependent manner, as is indicated by changes in the equilibrium between the folded and the unfolded NTD states and their equilibrium forces (Table 2). For example, at a constant mean force of 17.8 pN (Fig. 6C, black region in trace b), the SNARE complex frequently unzipped. However, upon Vc-57 binding, the complex primarily resided in the folded NTD state Fig. 6C, red region in trace b). The equilibrium change was also demonstrated by the change in the extension probability density distribution (Fig. 6D, compare black and red curves). As a result, frequent NTD transition was only seen at a higher force near its equilibrium force of ∼20 pN (Fig. 6 C and D). In addition, Vc-57 binding did not alter the average extension change accompanying the NTD transition (Fig. 6D and Table 2), ruling out any large structural change in the NTD induced by Vc-57. These observations indicated that Vc-57 binding significantly stabilized the NTD by inducing a subtle long-range conformational change, likely helix packing, in the t-SNARE complex. In contrast, Vc-53 and Vc-49 destabilized the NTD transition (Table 2), because both peptides partially blocked NTD folding (Fig. 4A) and decreased the extension changes of NTD transitions (Fig. 6D and Table 2). Based on extensive measurements of force-dependent NTD transitions, we derived NTD unfolding energies in the presence of four Vc peptides (Table 2). Whereas Vc-61 only slightly stabilized the NTD, Vc-57 increased the NTD unfolding energy by 5 (±2) kBT, significantly stabilizing the NTD. This comparison suggests that the ionic layer mediated the Vc-induced t-SNARE conformational switch that stabilized the NTD. In contrast, Vc-53 and Vc-49 destabilized the NTD progressively, because both peptides impeded NTD zippering.

Table 2.

Properties of the SNARE NTD folding in the absence (−) and presence of Vc peptides

| Vc peptide | Equilibrium force, pN | Extension, nm | Unfolding energy, kBT | Relative folding rate |

| — | 17.2 (0.5) | 6.7 (0.4) | 24 (2) | 1 |

| Vc-61 | 18.1 (0.8) | 6.7 (0.2) | 25 (1) | 6.0 (0.1) |

| Vc-57 | 20.2 (0.3) | 6.7 (0.2) | 29 (1) | 5.8 (0.1) |

| Vc-53 | 18.0 (0.9) | 5.2 (0.2) | 19 (1) | 4.1 (0.1) |

| Vc-49 | 15.0 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.3) | 12 (1) | 1.4 (0.2) |

Vc peptides also enhanced the rate of NTD folding in a length-dependent manner (Fig. 6C, Fig. S9B, and Table 2). The NTD of the native SNARE complex slowly assembles but readily disassembles upon vesicle undocking (8, 9), limiting the overall rate of SNARE assembly and membrane fusion. Munc18-1 and other regulatory proteins enhance NTD assembly to initiate SNARE zippering (17, 31, 32). Vc-57 significantly increased the rate and stability of NTD assembly, suggesting that this peptide efficiently activated the t-SNARE complex to initiate SNARE zippering. Other Vc peptides are predicted to promote SNARE zippering in a descending efficiency order of Vc-61, Vc-53, and Vc-49, consistent with their order of potency to activate membrane fusion (20). Vc-49 has been used widely to facilitate SNARE-mediated fusion (6, 20). Our results suggest that Vc-49 significantly destabilized NTD and only slightly enhanced the rate of NTD zippering. However, Vc-49 binds to the t-SNARE complex with the highest affinity among the four Vc peptides and may additionally promote SNARE zippering and membrane fusion by stabilizing the t-SNARE complex in the 1:1 complex (6). Alternatively, Vc peptides inhibit SNARE misassembly, such as formation of antiparallel SNARE bundles, thereby indirectly promoting functional SNARE assembly and membrane fusion (19). Note that the two mechanisms of Vc-enhanced SNARE assembly are not necessarily exclusive: The increased rate or energy of NTD zippering decreases the yield of SNARE misassembly due to kinetic or thermodynamic partitioning of the two processes. We expect that the N-terminal cross-linking in our SNARE constructs did not change the relative stability and rate of NTD assembly measured by us (Table 2 and Supporting Information). Our results demonstrate that Vc peptides not only enhanced the rate of NTD zippering (33) but also could stabilize the NTD in a length-dependent manner. Interestingly, Munc18-1 stabilized Tc and NTD zippering in a manner similar to Vc-57 (8), suggesting a common mechanism to promote initial SNARE zippering and membrane fusion directly or indirectly by regulating the t-SNARE conformation.

Discussion

Using optical tweezers, we measured the folding intermediates, energies, and kinetics of the synaptic t-SNARE complex and probed its long-range conformational change during SNARE zippering using Vn and Vc peptides. We derived a structural model for the t-SNARE complex in which the three SNARE motifs formed a three-helix bundle from −7 to +4 layers and were disordered from +5 to +8 layers. Our structural derivation assumed a particular t-SNARE folding pathway (Materials and Methods) and a homogeneous worm-like chain model for the polypeptide. We verified the derived structures by measurements on the t-SNARE complexes that were not cross-linked, cross-linked at four N-terminal sites, pulled from three different sites, mutated in syntaxin, split in SNAP-25, or bound by Vn and Vc. In contrast to other t-SNARE models (4, 10), the t-SNARE structure derived by us contains a fully ordered binding site (from −4 to +3 layers) for synaptotagmin (18) and a largely ordered binding site for complexin (19, 34). T-SNARE folding was robust under our experimental conditions. Thus, our results revealed a significantly more structured and stable t-SNARE complex than previous derivations and corroborated the bidirectional t-SNARE conformational change crucial for fast and regulated SNARE zippering (4, 8, 10, 24, 33). However, we did not test t-SNARE misfolding into the 2:1 complex, which is expected to be the primary t-SNARE misfolding pathway. In addition, t-SNARE stability and dynamics may be altered by membranes (4, 35), which were absent in our experiments.

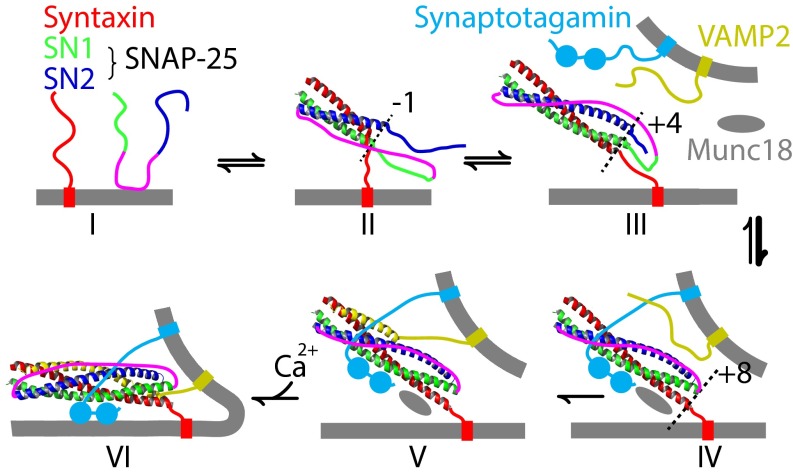

We propose a model to describe t-SNARE folding during membrane fusion (Fig. 7). First, the t-SNARE NTD slowly associates, forming the partially assembled t-SNARE complex (Fig. 7, states I–II). Subsequently, this complex spontaneously and reversibly folds into the full t-SNARE complex (Fig. 7, state III). Synaptotagmin and Munc18-1 then bind to the t-SNARE complex, docking the vesicle to the plasma membrane (14, 15, 18) (Fig. 7, state IV). Munc18-1 stabilizes the t-SNARE complex, which is required for efficient docking (15). Furthermore, Munc18-1 induces Tc folding and the NTD conformational change, activating the t-SNARE complex to initiate SNARE zippering (8, 32, 33). Note that Munc18-1 also binds to SNAREs in other modes that play crucial roles in SNARE assembly (8, 14, 31). Binding of v-SNARE NTD forms a half-zippered trans-SNARE complex, a process that is assisted by synaptotagmins, complexin, and other proteins (1, 19, 31) (Fig. 7, state V). The v-SNARE binding also stabilizes the t-SNARE CTD in the force-bearing trans-SNARE complex, which, in turn, stabilizes associations of regulatory proteins to the trans-SNARE complex. Finally, calcium triggers further zippering of v-SNARE along the stabilized t-SNARE template, leading to fast assembly of the SNARE four-helix bundle and subsequent membrane fusion (Fig. 7, state VI).

Fig. 7.

Model of t-SNARE folding and conformational changes in SNARE zippering and membrane fusion. The schematic states involved (not drawn to scale) are the monomeric t-SNAREs (I), the partially assembled t-SNARE complex (II), the folded t-SNARE complex (III), the activated t-SNARE complex (IV), the partially zippered trans-SNARE complex (V), and the zippered SNARE complex (VI).

Materials and Methods

SNARE Proteins.

The syntaxin construct comprised the cytoplasmic domain of rat syntaxin 1A (residues 1–265, with mutation C145S), a spacer sequence (GGSGNGGSGS), and a C-terminal Avi-tag (GLNDIFEAQKIEWHE). The genes corresponding to the syntaxin protein and mouse VAMP2 (residues 28–94) were cloned into the pET-SUMO vector (Thermo Fisher), whereas the SNAP-25B gene was inserted into the pET-28a vector. All proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells and purified using nickel nitrilotriacetic acid beads. The syntaxin protein was biotinylated in vitro using biotin ligase enzyme (BirA) as previously described (8, 9). The N-terminal His-tag and SUMO protein were cleaved from the purified syntaxin and VAMP2 proteins. Syntaxin, SNAP-25, and VAMP2 were mixed in a molar ratio of 1:1:2 in Hepes buffer containing 10 mM imidazole and 2 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. Ternary SNARE complexes were formed by incubating the mixture at 4 °C overnight and then purified using the N-terminal His-tag on SNAP-25.

High-Resolution Dual-Trap Optical Tweezers.

The optical tweezers were home-built as described (8). Briefly, a 1,064-nm laser beam was expanded, collimated, and split into two orthogonally polarized beams. The beams were focused by a water-immersion objective with a numerical aperture of 1.2 (Olympus) to form two optical traps. Displacements of the trapped beads were detected by back-focal plane interferometry. Optical tweezers were remotely operated through a computer interface written in LabVIEW (National Instruments).

Single-Molecule Protein Folding Experiment.

The purified SNARE complexes were cross-linked with the DNA handle as described before (9). An aliquot of the cross-linked protein/DNA conjugate was incubated with 1 μL of antidigoxigenin-coated polystyrene beads 2.17 μm in diameter (Spherotech), diluted to 1 mL of PBS, and injected into the top channel of a microfluidic chamber. Streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads 1.86 μm in diameter were injected into the bottom channel. Both top and bottom channels were connected to a central channel by capillary tubes, where both kinds of beads were trapped. A single SNARE complex was tethered between two beads by bringing them close. Data were recorded at 20 kHz, mean-filtered to 10 kHz, and stored on a hard disk. The single-molecule experiment was conducted in PBS at 23 (±1) °C. An oxygen scavenging system was added to prevent potential protein photodamage by optical traps.

Data Analysis.

Our methods are described in detail elsewhere (9, 26, 27). Briefly, the extension trajectories were analyzed by two- or three-state HMM, which yielded the probability, extension, force, lifetime, and transition rates for each state (27). To relate the experimental measurements to the conformations and energy (or the energy landscape) of the t-SNARE complex at zero force, we constructed a structural model for t-SNARE folding (26). In this model, three SNARE motifs were assumed to zipper synchronously layer by layer from the −7 layer toward the +8 layer, which established a t-SNARE folding pathway as a function of the reaction coordinate, with the contour length of the unfolded polypeptide stretched by optical tweezers. We chose the contour lengths and folding energies of the partially zippered and folded t-SNARE complexes as fitting parameters, which allowed us to calculate the total extension of the SNARE/DNA tether and the total energy of the tether and beads in optical traps. The extension and energy of the unfolded polypeptide, as well as the DNA handle, were calculated using the Marko–Siggia equation (25). The extension of the folded portion was derived from the t-SNARE structure in the ternary SNARE complex. From the calculated total energies for all states, we further evaluated the probability of each state based on the Boltzmann distribution and transition rates based on the Kramers equation. Finally, we fit the calculated state extensions, forces, probabilities, and transition rates to the corresponding experimental measurements using nonlinear least-squares fitting, which revealed the conformations and energies of different t-SNARE folding states as best-fit parameters.

Effects of Cross-Linking on the Folding or Binding Energy and Kinetics of Protein Complexes

We refer to cross-linking here as any method that links two macromolecules together via flexible linkers, including the cross-linking through disulfide bonds and fusion of two macromolecules into single polypeptides or polynucleotides. Covalent cross-linking has been used widely to study coupled folding and assembly of macromolecular complexes in both traditional experiments with an ensemble of molecules (36) and single-molecule experiments (9, 28, 37, 38). In particular, the cross-linking enables reversible folding/unfolding or binding/unbinding transitions of proteins in single-molecule manipulation experiments under equilibrium conditions, which is pivotal for measurements of the energy associated with these transitions. However, cross-linking significantly changes the kinetics of protein folding and subtly alters the folding energy (28, 36). It is generally unclear how the energy and kinetics measured in the presence of cross-linking are related to the energy and kinetics measured in its absence. Previous experiments have compared folding of the GCN4 coiled-coil with and without N-terminal cross-linking (36) and laid a framework to examine the effects of cross-linking in single-molecule manipulation experiments (28, 37). Here, we present a simple theory to quantify the effects of cross-linking on the energetics and kinetics of protein folding. We will first justify our theory using previous experimental measurements and then calculate the folding energy of the t-SNARE complex in the absence of cross-linking. To simplify our following analysis, we assume that the energetics and kinetics of the cross-linked protein complexes at zero force have already been determined (26). Our purpose here is to derive the folding or binding energy and kinetics in the absence of cross-linking and external force. We will briefly discuss the effects of cross-linking on the energetics and kinetics of protein folding in the presence of force at the end of Supporting Information.

The Linker.

The basic function of the cross-linking used in protein folding studies is to tether the two proteins together, which increases the local concentration of one protein at the other and facilitates their association or folding. To this end, the two proteins are generally cross-linked outside the regions that are involved in protein folding and binding via a flexible peptide linker. Note that the main function of the linker is to keep the two unfolded or unbound proteins in proximity. In this case, the linker needs to be better defined. We define the linker to be the disordered polypeptide between the middle amino acids of the protein domains if the domains are unfolded upon unbinding or the first structured amino acids to which the linker is attached if the domains remain structured upon unbinding (Fig. S5). For example, the NTDs of syntaxin and SN1 or SN2 are involved in the initial dimerization during t-SNARE folding, and the middle amino acids are in the hydrophobic layer −4 (i.e., syntaxin 1A L212, SNAP-25B S39 or L160) (Fig. 1A). Because both proteins are completely unfolded, the linker is the polypeptide that connects the two middle amino acids, including the cross-linking site (Fig. S5A), giving the linker length shown in Table S1 for the six t-SNARE constructs used in this study. To validate our method, we first examined the effects of cross-linking on two proteins, the GCN4 coiled-coil and α-chain of the glycoprotein Ib (GPIbα)– filamin domain 21 (FLNa21) complex, that have been studied (36, 37). We determined the linker length of the GCN4 coiled-coil in a way similar to the linker length of the t-SNARE constructs. The GPIbα–FLNa21 complex is special. Association between FLNa21 and the C-terminal peptide in GPIbα is involved in force sensing and signal transduction across plasma membranes (37). To study the interaction between the two proteins using optical tweezers, Rognoni et al. (37) fused the 13 amino acids of GPIbα to the N terminus of the isolated FLNa21 via a 6-aa glycine-serine spacer and pulled the complex from the N and C termini of the fusion protein (Fig. S5B). In this case, the linker is the 19 amino acids illustrated in Fig. S5B, including seven amino acids in GPIbα, the 6-aa spacer, and six disordered amino acids in FLNa21 (37). The contour length () of a polypeptide with amino acids is nm, in which 0.365 nm is the average contour length per amino acid (9).

Effective Protein Concentration.

Given the contour length () and the persistence length (P = 0.6 nm) of the disordered polypeptide tethering two proteins, the effective concentration of one end of the linker at the other () can be expressed as

| [S1] |

where is the distance between the two ends of the linker and is Avogadro’s number (39). Here, we have treated the linker as a Gaussian chain. We determined the distance required for protein binding based on the crystal structure of the protein complex (Fig. S5). For the coiled-coil proteins, we chose nm as the distance between the axes of two α-helices (Fig. S5A), compared with the average 1.2-nm diameter of an α-helix. For the GPIbα–FLNa21 complex, we adopted nm, as illustrated in Fig. S5B. Using Eq. S1 and these parameters, we calculated the effective concentrations of the eight cross-linked protein complexes (Table S1). The effective concentrations vary in the range of 2–11 mM. This high concentration generally cannot be achieved by directly adding proteins in the solution, necessitating the cross-linking method. For GCN4 coiled-coil and the GPIbα–FLNa21 complex, the predicted effective concentrations are remarkably close to the corresponding measured values. The consistency verifies our method of computing the effective concentration. For the same protein complex, changing the cross-linking site is equivalent to the protein titration used in a typical experiment to test binding of two proteins. Consequently, the four t-SNARE constructs used in our studies vary the effective concentration from 2.4 mM for −16C to 9.7 mM for −8C.

Binding Kinetics and Energy.

The bimolecular association rate constant in the absence of cross-linking () is related to the binding or folding rate constant () in the presence of cross-linking by the following equation:

| [S2] |

This formula is also used to derive the effective concentration listed in Table S1 as the measured effective concentration, given the measurements of and . Note that cross-linking does not change the unfolding or dissociation rate constant, as long as the cross-linking only serves as a tether and does not alter the structure of the folded proteins. In addition, cross-linking leads to an energy correction () for the dissociation energy or unfolding energy of the protein complex in the absence of cross-linking ():

| [S3] |

and

| [S4] |

where is the unfolding energy of the cross-linked protein complex and the effective concentration () has a molar unit. Because of the millimolar range of the effective concentration, Eq. S4 immediately suggests that the unfolding energy measured for the cross-linked protein complex is smaller than the bimolecular dissociation energy defined under a standard condition with 1 M concentration of the reactant, consistent with previous experimental results (36, 37). As a result, we obtained an energy correction in the range of 4.5–6 kBT, which does not significantly change with the linker length (28). The conclusion is expected, because for small , as shown by Eqs. S1 and S4. Furthermore, the energy corrections obtained for the GCN4 and the GPIbα–FLNa21 complex are close to their experimental measurements (Table S1), again verifying our theory. Using the calculated energy corrections for the t-SNARE constructs, we obtained the NTD dissociation or unfolding energy shown in Table 1.

Effects of Cross-Linking in the Presence of Force.

The above calculations show that, in the absence of force, changing the linker length does not dramatically change the effective concentration and the energy correction. As a result, the folding energy measured for the same protein complex at zero force, but with a different size of the linker, does not significantly change, a phenomenon that has widely been observed in previous studies (28). This observation can be understood from Eqs. S3 and S4: Because only weakly depends on the linker size and is a constant for a given protein complex, the unfolding energy () must also weakly depend on the linker size. The similar unfolding energies of the t-SNARE complexes in −8C and SN2C (Table 1) also suggest that the amino acids near the −8 layer (Fig. 1A) are disordered. If the amino acids near or N-terminal to the −8 layer contribute to t-SNARE folding, the unfolding energy of SN2C would be higher than the unfolding energy of −8C.

However, in the presence of a constant force (), changing the linker size dramatically changes the equilibrium folding and unfolding kinetics of the cross-linked protein complexes, as shown by our experimental results (compare Figs. 2A, 2C, and 4C; also Fig. S5) and previous results (28). This observation is expected, because protein refolding needs to shorten the linker extension against the stretching force (), leading to an increase in the energy barrier for protein folding (i.e., ). Therefore, the folding rate decreases exponentially as the linker length increases. In addition, because the unfolding rate does not change with the linker length, the equilibrium force (the force with equal folding and unfolding rates) decreases as the linker length increases (compare Fig. 2 A and C).

Acknowledgments

We thank Axel Brunger and Erdem Karatekin for discussion and Tong Shu for help. This work was supported by the NIH Grants GM093341 (to Y. Z.), GM071458 (to J.E.R.), and T32GM007223, and by the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Institute at Yale.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1605748113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Südhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: Grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323(5913):474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Söllner T, et al. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature. 1993;362(6418):318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1998;395(6700):347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weninger K, Bowen ME, Choi UB, Chu S, Brunger AT. Accessory proteins stabilize the acceptor complex for synaptobrevin, the 1:1 syntaxin/SNAP-25 complex. Structure. 2008;16(2):308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasshauer D, Margittai M. A transient N-terminal interaction of SNAP-25 and syntaxin nucleates SNARE assembly. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7613–7621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pobbati AV, Stein A, Fasshauer D. N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly promotes rapid membrane fusion. Science. 2006;313(5787):673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter AM, Wiederhold K, Bruns D, Fasshauer D, Sørensen JB. Synaptobrevin N-terminally bound to syntaxin-SNAP-25 defines the primed vesicle state in regulated exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;188(3):401–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma L, et al. Munc18-1-regulated stage-wise SNARE assembly underlying synaptic exocytosis. eLife. 2015;4:e09580. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, et al. Single reconstituted neuronal SNARE complexes zipper in three distinct stages. Science. 2012;337(6100):1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1224492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F, et al. A half-zippered SNARE complex represents a functional intermediate in membrane fusion. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(9):3456–3464. doi: 10.1021/ja410690m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber T, et al. SNAREpins: Minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92(6):759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pertsinidis A, et al. Ultrahigh-resolution imaging reveals formation of neuronal SNARE/Munc18 complexes in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(30):E2812–E2820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310654110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles MK, et al. Single secretory granules of live cells recruit syntaxin-1 and synaptosomal associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) in large copy numbers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(48):20810–20815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014840107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawidowski D, Cafiso DS. Munc18-1 and the Syntaxin-1 N terminus regulate open-closed states in a t-SNARE complex. Structure. 2016;24(3):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Wit H, et al. Synaptotagmin-1 docks secretory vesicles to syntaxin-1/SNAP-25 acceptor complexes. Cell. 2009;138(5):935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasshauer D, Eliason WK, Brünger AT, Jahn R. Identification of a minimal core of the synaptic SNARE complex sufficient for reversible assembly and disassembly. Biochemistry. 1998;37(29):10354–10362. doi: 10.1021/bi980542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen J, Tareste DC, Paumet F, Rothman JE, Melia TJ. Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell. 2007;128(1):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Q, et al. Architecture of the synaptotagmin-SNARE machinery for neuronal exocytosis. Nature. 2015;525(7567):62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature14975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi UB, Zhao M, Zhang Y, Lai Y, Brunger AT. Complexin induces a conformational change at the membrane-proximal C-terminal end of the SNARE complex. eLife. 2016;5:e16886. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melia TJ, et al. Regulation of membrane fusion by the membrane-proximal coil of the t-SNARE during zippering of SNAREpins. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(5):929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreutzberger AJB, Liang B, Kiessling V, Tamm LK. Assembly and comparison of plasma membrane SNARE acceptor complexes. Biophys J. 2016;110(10):2147–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez JM, et al. Membrane fusion intermediates via directional and full assembly of the SNARE complex. Science. 2012;336(6088):1581–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.1221976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W, Stout RF, Jr, Parpura V. Ternary SNARE complexes in parallel versus anti-parallel orientation: Examination of their disassembly using single-molecule force spectroscopy. Cell Calcium. 2012;52(3-4):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiebig KM, Rice LM, Pollock E, Brunger AT. Folding intermediates of SNARE complex assembly. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(2):117–123. doi: 10.1038/5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marko JF, Siggia ED. Stretching DNA. Macromolecules. 1995;28:8759–8770. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rebane AA, Ma L, Zhang Y. Structure-based derivation of protein folding intermediates and energies from optical tweezers. Biophys J. 2016;110(2):441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang YL, Jiao J, Rebane AA. Hidden Markov modeling with detailed balance and its application to single protein folding. Biophys J. 2016;111(10):2110–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodside MT, et al. Nanomechanical measurements of the sequence-dependent folding landscapes of single nucleic acid hairpins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(16):6190–6195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An SJ, Almers W. Tracking SNARE complex formation in live endocrine cells. Science. 2004;306(5698):1042–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.1102559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misura KMS, Gonzalez LC, Jr, May AP, Scheller RH, Weis WI. Crystal structure and biophysical properties of a complex between the N-terminal SNARE region of SNAP25 and syntaxin 1a. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(44):41301–41309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker RW, et al. A direct role for the Sec1/Munc18-family protein Vps33 as a template for SNARE assembly. Science. 2015;349(6252):1111–1114. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munch AS, et al. Extension of Helix 12 in Munc18-1 induces vesicle priming. J Neurosci. 2016;36(26):6881–6891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0007-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Tiwari N, Rothman JE, Pincet F. Kinetic barriers to SNAREpin assembly in the regulation of membrane docking/priming and fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(38):10536–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kümmel D, et al. Complexin cross-links prefusion SNAREs into a zigzag array. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(8):927–933. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su Z, Ishitsuka Y, Ha T, Shin YK. The SNARE complex from yeast is partially unstructured on the membrane. Structure. 2008;16(7):1138–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran LB, Schneider JP, Kentsis A, Reddy GA, Sosnick TR. Transition state heterogeneity in GCN4 coiled coil folding studied by using multisite mutations and crosslinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(19):10699–10704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rognoni L, Stigler J, Pelz B, Ylänne J, Rief M. Dynamic force sensing of filamin revealed in single-molecule experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(48):19679–19684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211274109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Y, Sirinakis G, Zhang Y. Highly anisotropic stability and folding kinetics of a single coiled coil protein under mechanical tension. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(32):12749–12757. doi: 10.1021/ja204005r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plischke M, Bergersen B. Equilibrium Statistical Physics. 3rd Ed World Scientific Publishing Co.; Singapore: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiema T, et al. The molecular basis of filamin binding to integrins and competition with talin. Mol Cell. 2006;21(3):337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]