Significance

Alcohol is a widely consumed drug in western societies that can lead to addiction. A small shift in consumption can have dramatic consequences on public health. We performed the largest genome-wide association metaanalysis and replication study to date (>105,000 individuals) and identified a genetic basis for alcohol consumption during nonaddictive drinking. We found that a locus in the gene encoding β-Klotho is associated with alcohol consumption. β-Klotho is an essential receptor component for the endocrine FGFs, FGF19 and FGF21. Using mouse models and pharmacologic administration of FGF21, we show that β-Klotho in the brain controls alcohol drinking. These findings reveal a mechanism regulating alcohol consumption in humans that may be pharmacologically tractable for reducing alcohol intake.

Keywords: alcohol consumption, human, β-Klotho, FGF21, mouse model

Abstract

Excessive alcohol consumption is a major public health problem worldwide. Although drinking habits are known to be inherited, few genes have been identified that are robustly linked to alcohol drinking. We conducted a genome-wide association metaanalysis and replication study among >105,000 individuals of European ancestry and identified β-Klotho (KLB) as a locus associated with alcohol consumption (rs11940694; P = 9.2 × 10−12). β-Klotho is an obligate coreceptor for the hormone FGF21, which is secreted from the liver and implicated in macronutrient preference in humans. We show that brain-specific β-Klotho KO mice have an increased alcohol preference and that FGF21 inhibits alcohol drinking by acting on the brain. These data suggest that a liver–brain endocrine axis may play an important role in the regulation of alcohol drinking behavior and provide a unique pharmacologic target for reducing alcohol consumption.

Excessive alcohol consumption is a major public health problem worldwide, causing an estimated 3.3 million deaths in 2012 (1). Much of the behavioral research associated with alcohol has focused on alcohol-dependent patients. However, the burden of alcohol-associated disease largely reflects the amount of alcohol consumption in a population, not alcohol dependence (2). It has long been recognized that small shifts in the mean of a continuously distributed behavior, such as alcohol drinking, can have major public health benefits (3). For example, a shift from heavy to moderate drinking could have beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease risk (4).

Alcohol drinking is a heritable complex trait (5). Genetic variants in the alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family can result in alcohol intolerance caused by altering peripheral alcohol metabolism and may thus influence alcohol consumption and dependence (6). However, genetic influences on brain functions affecting drinking behavior have been more difficult to detect, because as for many complex traits, the effect of individual genes is small, and therefore, large sample sizes are required to detect the genetic signal (7).

Here, we report a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and replication study of over 100,000 individuals of European descent. We identify a gene variant in β-Klotho (KLB) that associates with alcohol consumption. β-Klotho is a single-pass transmembrane protein that complexes with FGF receptors to form cell surface receptors for the hormones FGF19 and FGF21 (8, 9). FGF19 is induced by bile acids in the small intestine to regulate bile acid homeostasis and metabolism in the liver (9). FGF21 is induced in liver and released into the blood in response to various metabolic stresses, including high-carbohydrate diets and alcohol (10–12). Notably, FGF21 was recently associated in a human GWAS study with macronutrient preference, including changes in carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake (13). Moreover, FGF21 was shown to suppress sweet and alcohol preference in mice (14, 15). Our findings suggest that the FGF21-β-Klotho signaling pathway regulates alcohol consumption in humans.

Results

Association of KLB Gene SNP rs11940694 with Alcohol Drinking in Humans.

We carried out a GWAS of quantitative data on alcohol intake in 70,460 individuals (60.9% women) of European descent from 30 cohorts. We followed up the most significantly associated SNPs (six sentinel SNPs; P < 1.0 × 10−6 from independent regions) among up to 35,438 individuals from 14 additional cohorts (SI Appendix and Dataset S1). We analyzed both continuous data on daily alcohol intake in drinkers (as grams per day; log transformed) and a dichotomous variable of heavy vs. light or no drinking (Dataset S1). Average alcohol intake in drinkers across the samples was 14.0 g/d in men and 6.0 g/d in women. We performed per-cohort sex-specific and combined sex single-SNP regression analyses under an additive genetic model and conducted metaanalyses across the sex-specific strata and cohorts using an inverse variance weighted fixed effects model.

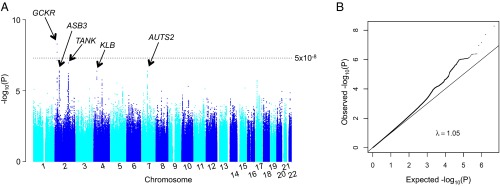

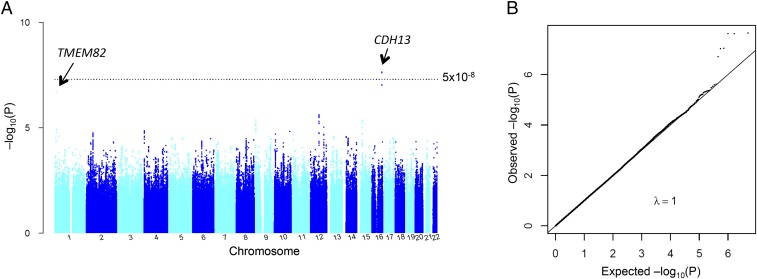

Results of the primary GWAS for log grams per day alcohol are shown in Fig. 1, Dataset S2, and Fig. S1. We identified five SNPs for replication at P < 1 × 10−6: rs11940694 in the KLB gene, rs197273 in TRAF family member-associated NF-κB (TANK), rs780094 in GCKR, rs350721 in ASB3, and rs10950202 in AUTS2 (Table 1 and Dataset S2). In addition to rs10950202 in AUTS2 (P = 2.9 × 10−7), we took forward SNP rs6943555 in AUTS2 (P = 1.4 × 10−4), which was previously reported in relation to alcohol drinking (7). In both men and women, the SNPs were all significantly associated with log grams per day alcohol at P < 0.005 (Table S1). When combining discovery and replication data, we observed genome-wide significance for SNP rs11940694 (A/G) in KLB (P = 9.2 × 10−12) (Table 1 and Fig. S1), for which the minor allele A was associated with reduced drinking. KLB is localized on human chromosome 4p14 and encodes a transmembrane protein, β-Klotho, which is an essential component of receptors for FGF19 and FGF21 (8, 9). rs197273 in the TANK gene narrowly missed reaching genome-wide significance in the combined sample (Table 1) (P = 7.4 × 10−8). In the dichotomous analysis of the primary GWAS, SNP rs12599112 in the Cadherin 13 gene and rs10927848 in the Transmembrane protein 82 gene were significant at P = 2.3 × 10−8 and P = 2.6 × 10−7, respectively (Dataset S2, Fig. S2, and Table S2), but they did not reach genome-wide significance in the combined analysis (Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide association results of log grams per day alcohol in the Alcohol Genome-Wide Association (AlcGen) and Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Plus (CHARGE+) Consortia. (A) Manhattan plot showing the significance of the association (−log10-transformed P value on the y axis) for each SNP at the chromosomal position shown on the x axis. The dotted line represents the genome-wide significance level at P = 5 × 10−8. The genes that were followed up are labeled. (B) Quantile–quantile plot comparing the expected P value on the x axis and the observed P value on the y axis (both were −log10 transformed).

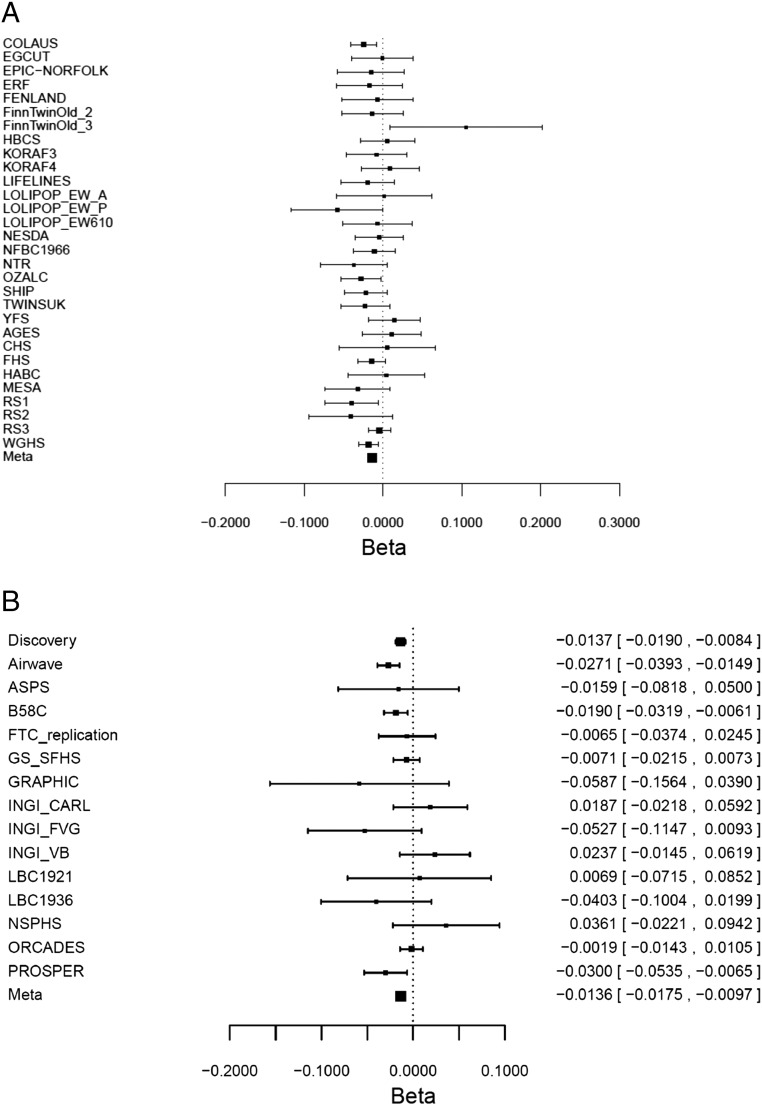

Fig. S1.

Forest plot for the association of rs11940694 in KLB with log grams per day alcohol in the discovery GWAS and replication cohorts. (A) rs11940694 in KLB in discovery GWAS cohorts. Discovery GWAS cohorts: the Alcohol Genome-Wide Association (AlcGen) Consortium: the Cohorte Lausannoise study (COLAUS), the Estonian Biobank Cohort (EGCUT), the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer–Norfolk study (EPIC-NORFOLK), the Erasmus Rucphen Family study (ERF), the Fenland study (FENLAND), the Older Finnish Twin Cohort_2 (FinnTwinOld_2), the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS), the population-based Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg F3 Study (KORAF3), the population-based Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg F4 Study (KORAF4), the LifeLines Cohort Study & Biobank (LIFELINES), the London Life Sciences Prospective Population Study (LOLIPOP_EW_A, LOLIPOP_EW_P, and LOLIPOP_EW610), the Older Finnish Twin Cohort_3 (FinnTwinOld_3), the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 (NFBC1996), the Netherlands Twin Register cohort (NTR), the Australian twin-family study of alcohol use disorder (OZALC), the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP), the TwinsUK study (TWINSUK), and the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study (YFS); and the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Plus (CHARGE+) Consortium: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik (AGES-Reykjavik) study, the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (HABC), the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), the Rotterdam Study (RS1, RS2, and RS3), and the Women's Genome Health Study (WGHS). In rs11940694, the coded allele was A, and the noncoded allele was G. The allele frequency for A was ∼0.42 in the entire sample. The beta/SE estimates were for A allele. (B) rs11940694 in KLB in discovery and replication cohorts. The coded allele was A, and the noncoded allele was G. The beta/SE estimates were for A allele.

Table 1.

Associations of SNPs with alcohol intake (log grams per day) in the GWAS analysis

| SNP | Chr | Position (hg 19) | Nearest gene | Effect/other alleles | EAF | Discovery GWAS | Replication | Combined | ||||

| Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | N | ||||||

| rs780094 | 2 | 27,741,237 | GCKR | T/C | 0.40 | −0.0155 (0.0026) | 3.6 × 10−9 | 0.0035 (0.0029) | 0.238 | −0.0102 (0.0019) | 1.6 × 10−7 | 98,679 |

| rs350721 | 2 | 52,980,427 | ASB3 | C/G | 0.18 | 0.0206 (0.0040) | 3.2 × 10−7 | −0.0000 (0.0042) | 0.994 | 0.0109 (0.0029) | 1.9 × 10−4 | 100,859 |

| rs197273 | 2 | 161,894,663 | TANK | A/G | 0.49 | −0.0141 (0.0026) | 9.8 × 10−8 | −0.0058 (0.0028) | 0.040 | −0.0103 (0.0019) | 7.4 × 10−8 | 97,631 |

| rs11940694 | 4 | 39,414,993 | KLB | A/G | 0.42 | −0.0137 (0.0027) | 3.2 × 10−7 | −0.0135 (0.0030) | 5.2 × 10−6 | −0.0136 (0.0020) | 9.2 × 10−12 | 98,477 |

| rs6943555 | 7 | 698,060,23 | AUTS2 | A/T | 0.29 | −0.0115 (0.0030) | 1.4 × 10−4 | −0.0070 (0.0033) | 0.032 | −0.0094 (0.0022) | 1.9 × 10−5 | 104,282 |

| rs10950202 | 7 | 69,930,098 | AUTS2 | G/C | 0.16 | −0.0194 (0.0038) | 2.9 × 10−7 | −0.0015 (0.0042) | 0.720 | −0.0113 (0.0028) | 5.9 × 10−5 | 105,639 |

One SNP with the smallest P value was taken forward per region. Chr, chromosome; EAF, effect allele frequency in the discovery GWAS.

Table S1.

Sex-specific associations of SNPs taken forward for replication from discovery GWAS

| Alcohol phenotype | SNP | Gene | Chr | Position | Effect allele | Other allele | Men | Women | ||||

| Effect* | SE | P value | Effect | SE | P value | |||||||

| Log g/d | rs780094 | GCKR | 2 | 27,594,741 | T | C | −0.016 | 0.004 | 2.8 × 10−4 | −0.014 | 0.003 | 2.0 × 10−5 |

| Log g/d | rs197273 | TANK | 2 | 161,602,909 | A | G | −0.018 | 0.004 | 6.5 × 10−5 | −0.010 | 0.003 | 2.1 × 10−3 |

| Log g/d | rs10950202 | AUTS2 | 7 | 69,568,034 | C | G | 0.022 | 0.006 | 5.7 × 10−4 | 0.017 | 0.005 | 5.1 × 10−4 |

| Log g/d | rs11940694 | KLB | 4 | 39,091,388 | A | G | −0.019 | 0.004 | 2.3 × 10−5 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 8.9 × 10−4 |

| Log g/d | rs350721 | ASB3 | 2 | 52,833,931 | C | G | 0.023 | 0.007 | 5.7 × 10−4 | 0.020 | 0.005 | 5.7 × 10−5 |

| Log g/d | rs6943555 | AUTS2 | 7 | 69,806,023 | A | T | −0.013 | 0.005 | 9.9 × 10−3 | −0.011 | 0.004 | 3.3 × 10−3 |

| Dichotomous | rs12599112 | CDH13 | 16 | 81,276,212 | A | C | 0.053 | 0.091 | 0.561 | −0.063 | 0.015 | 2.4 × 10−5 |

| Dichotomous | rs10927848 | TMEM82 | 1 | 15,948,493 | A | G | 0.027 | 0.036 | 0.452 | −0.023 | 0.008 | 2.5 × 10−3 |

Chr, chromosome; EAF, effect allele frequency; CDH13, Cadherin 13; TMEM82, Transmembrane protein 82.

Effect refers to beta coefficient from linear regression for log grams per day alcohol phenotype and log(odds ratio) from logistic regression for dichotomous alcohol phenotype.

Fig. S2.

Genome-wide association results of dichotomous alcohol in the Alcohol Genome-Wide Association (AlcGen) and Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiolog Plus (CHARGE+) consortia. (A) Manhattan plot showing the significance of the association (−log10-transformed P value on the y axis) for each SNP at the chromosomal position shown on the x axis. The dotted line represents the genome-wide significance level at P = 5 × 10−8. The genes that were followed up are labeled. (B) Quantile–quantile plot comparing the expected P value on the x axis and the observed P value on the y axis (both were −log10 transformed).

Table S2.

Dichotomous trait replication results

| SNP | Chr | Position (hg19) | Gene* | Discovery P | Replication P | Overall P | Overall N |

| rs12599112 | 16 | 82,718,711 | CDH13 | 2.3 × 10−8 | 0.895 | 5.0 × 10−8 | 86,213 |

| rs10927848 | 1 | 16,075,906 | TMEM82 | 2.6 × 10−7 | 0.291 | 1.9 × 10−7 | 103,219 |

Cohorts: the Airwave Health Monitoring Study (Airwave), the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study (ASPS), the British 1958 birth cohort (B58C), the Finnish Twin Cohort replication sample (FinnTwin_replication), the Genetic Regulation of Arterial Pressure of Humans in the Community Study (GRAPHIC), the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS), the INGI– Carlantino study (INGI_CARL), the INGI– Friuli Venezia Giulia study (INGI_FVG), the INGI–Val Borbera study (INGI_VB), the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921 (LBC1921), the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (LBC1936), and the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER). The most significant SNP per locus is displayed. Chr, chromosome; CDH13, Cadherin 13; TMEM82, Transmembrane protein 82.

Loci are named according to the closest gene based on the position of the most significant SNP.

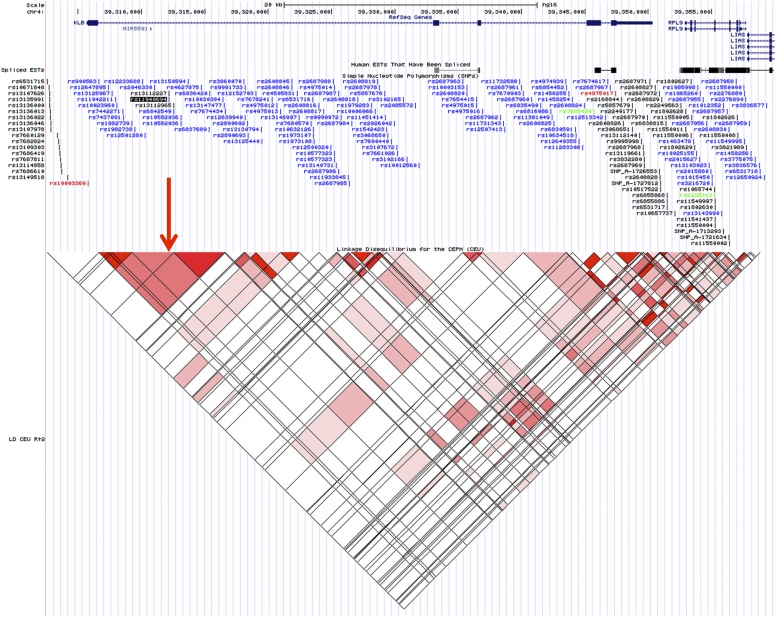

SNP rs11940694 is localized in intron 1 of the KLB gene. The local linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of the KLB gene is shown in Fig. S3. The minor allele frequencies of this SNP were generally high (between 0.37 and 0.44) in different ethnic groups (Table S3). We found no significant association of rs11940694 with gene expression in peripheral blood of 5,236 participants of the Framingham Heart Study (Tables S4 and S5) (16).

Fig. S3.

Illustration of common SNPs (minor allele frequency > 0.01) and LD structure in the genomic regions around the KLB gene. The target SNP rs11940694 is highlighted with the black background and indicated by a red arrow in the LD structure plot. LD is measured by r2, and the darker the red color, the higher the r2 value.

Table S3.

Allele frequencies of the KLB SNP rs11940694 in different ethnic groups

| Ethnicity | Sample (2N) | Major allele frequency | Minor allele frequency |

| Admixture American | 694 | A = 0.565 | G = 0.435 |

| African | 1,322 | G = 0.570 | A = 0.430 |

| East Asian | 1,008 | A = 0.541 | G = 0.459 |

| South Asian | 978 | A = 0.630 | G = 0.370 |

| European | 1,006 | G = 0.612 | A = 0.388 |

Table S4.

Gene expression in peripheral blood in the Framingham Heart Study: Demographics for gene expression analysis

| Phenotypes/covariates | Offspring cohort (examination cycle 8: 2005–2008) | Third generation cohort (examination cycle 2: 2008–2011) |

| Gene expression analysis | n = 2,222 | n = 3,014 |

| Female (%) | 1,221 (54.95) | 1,603 (53.10) |

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 66.41 (8.95) | 46.88 (8.79) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.04 (5.87) | 28.31 (5.5.30) |

BMI, body mass index.

Table S5.

Gene expression in peripheral blood in the Framingham Heart Study: Association of KLB SNP rs11940694 with gene expression

| SNP | Chr | Position | Effect allele | Beta | P value |

| rs11940694 | 4 | 39,414,993 | A | 0.00409 | 0.165 |

Chr, chromosome.

β-Klotho in the Brain Controls Alcohol Drinking in Mice.

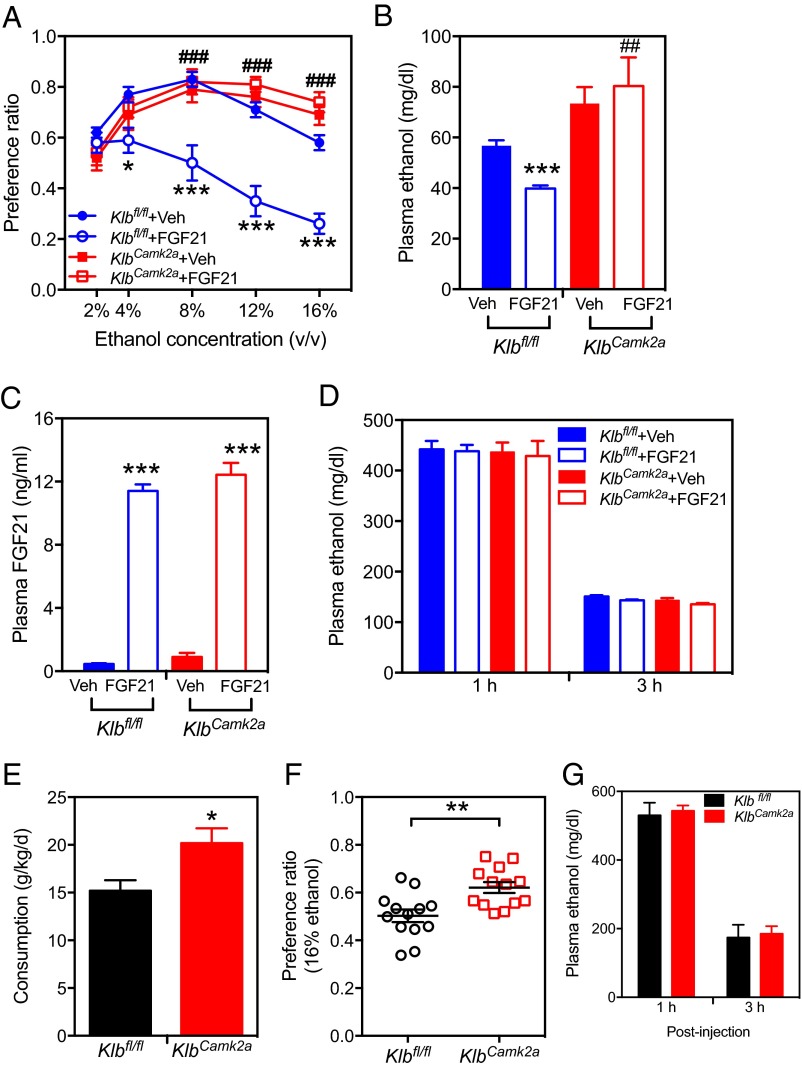

To examine whether β-Klotho affects alcohol drinking in mice and whether it does so through actions in the brain, we measured alcohol intake and the alcohol preference ratio of brain-specific β-Klotho KO (KlbCamk2a) mice and control floxed Klb (Klbfl/fl) mice. We used a voluntary two-bottle drinking assay performed with water and alcohol. Because we previously showed that FGF21-transgenic mice, which express FGF21 at pharmacologic levels, have a reduced alcohol preference (14), we performed these studies while administering either recombinant FGF21 or vehicle by osmotic minipump. Alcohol preference vs. water was significantly increased in vehicle-treated KlbCamk2a compared with Klbfl/fl mice at 16 vol % alcohol (Fig. 2A). FGF21 suppressed alcohol preference in Klbfl/fl mice but not in KlbCamk2a mice, showing that the effect of FGF21 on alcohol drinking depends on β-Klotho expressed in the brain (Fig. 2A). There was a corresponding decrease in plasma alcohol levels immediately after 16 vol % alcohol drinking, which reflects the modulation of the drinking behavior (Fig. 2B). However, plasma FGF21 levels were comparable in Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice administered recombinant FGF21 at the end of the experiment (Fig. 2C). Alcohol bioavailability was not different between FGF21-treated Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice (Fig. 2D). We have previously shown that FGF21 decreases the sucrose and saccharin preference ratio in Klbfl/fl but not KlbCamk2a mice and has no effect on the quinine preference ratio (14). To rule out a potential perturbation of our findings as a result of the experimental procedure, we independently measured preference and consumption of 16 vol % alcohol in Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice without osmotic minipump implantation. Again, KlbCamk2a mice showed significantly greater alcohol consumption and increased alcohol preference compared with Klbfl/fl mice (Fig. 2 E and F), thus replicating our findings above. Alcohol bioavailability after an i.p. injection was not different between Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice after 1 and 3 h (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

FGF21 reduces alcohol preference in mice by acting on β-Klotho in brain. (A) Alcohol preference ratios determined by two-bottle preference assays with water and the indicated ethanol concentrations for control (Klbfl/fl) and brain-specific KlbCamk2a mice administered either FGF21 (0.7 mg/kg per day) or vehicle (n = 10 per group). (B) Plasma ethanol and (C) FGF21 concentrations at the end of the 16% (vol/vol) ethanol step of the two-bottle assay. For A–C, ***P < 0.001 for Klbfl/fl + vehicle vs. Klbfl/fl + FGF21 groups; ##P < 0.01 for Klbfl/fl + FGF21 vs. KlbCamk2a + FGF21 groups as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's posttests; ###P < 0.001 for Klbfl/fl + FGF21 vs. KlbCamk2a + FGF21 groups as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's posttests. (D) Plasma ethanol concentrations 1 and 3 h after i.p. injection of 2 g/kg alcohol (n = 4 per each group). (E) Consumption of 16% (vol/vol) ethanol (grams per kilogram per day) and (F) alcohol preference ratios in two-bottle preferences assays performed with control (Klbfl/fl) and brain-specific KlbCamk2a mice. Alcohol preference was measured by volume of ethanol/total volume of fluid consumed (n = 13 per group). (G) Plasma ethanol concentrations 1 and 3 h after i.p. injection of 2 g/kg alcohol (n = 5 per group). Values are means ± SEM. For E and F, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

β-Klotho in Brain Does Not Regulate Emotional Behavior in Mice.

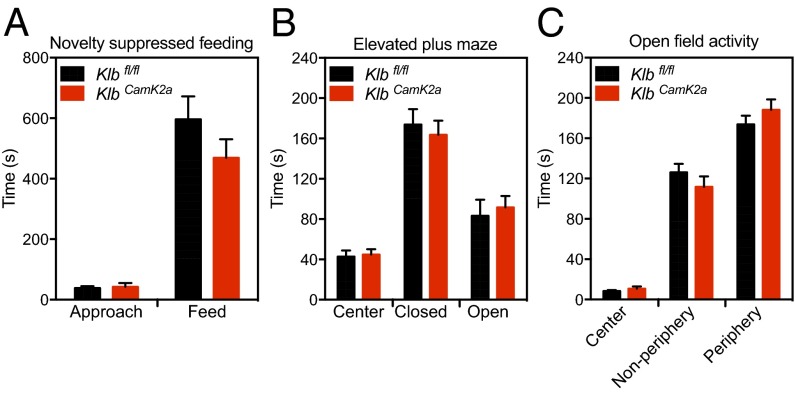

Increased alcohol drinking in humans and mice may be motivated by its reward properties or as a means to relieve anxiety and stress (17). In mice, FGF21 increases corticotropin-releasing hormone expression in hypothalamus, circulating glucocorticoid concentrations, and sympathetic outflow (18–20), which are linked to heightened anxiety. We, therefore, tested Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice in behavioral paradigms measuring anxiety, including novelty suppressed feeding (Fig. 3A), elevated plus maze (Fig. 3B), and open-field activity tests (Fig. 3C). However, we did not find differences between Klbfl/fl and KlbCamk2a mice in any of these anxiety measures or general locomotor activity. Our finding of increased alcohol preference in KlbCamk2a mice may thus be caused by alteration of alcohol-associated reward mechanisms. Although this notion is consistent with our previous results showing Klb expression in areas important for alcohol reinforcement, specifically the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area (14), additional studies will be required to determine precisely where in the brain and how β-Klotho affects alcohol drinking.

Fig. 3.

Behavior tests in brain-specific KlbCamk2a mice. Results from (A) novelty suppressed feeding, (B) elevated plus maze, and (C) open-field activity assays performed with control (Klbfl/fl) and brain-specific KlbCamk2a mice (n = 15 per each group). Values are the time (seconds) spent for each step of the assay.

Discussion

Here, we report that, in a GWAS performed in over 100,000 individuals, SNP rs11940694 in KLB associates with alcohol consumption in nonaddicts. We further show that mice lacking β-Klotho in the brain have increased alcohol consumption and are refractory to the inhibitory effect of FGF21 on alcohol consumption. These findings reveal a previously unrecognized brain pathway regulating alcohol consumption in humans that may prove pharmacologically tractable for suppressing alcohol drinking.

FGF21 is induced in liver by simple sugars through a mechanism involving the transcription factor carbohydrate response element binding protein (10, 11, 15, 21, 22). FGF21, in turn, acts on brain to suppress sweet preference (14, 15). Thus, FGF21 is part of a liver–brain feedback loop that limits the consumption of simple sugars. Notably, FGF21 is also strongly induced in liver by alcohol and contributes to alcohol-induced adipose tissue lipolysis in a mouse model of chronic binge alcohol consumption (12). Our data suggest the existence of an analogous feedback loop, wherein liver-derived FGF21 acts on brain to limit the consumption of alcohol. However, additional studies will be required to establish the existence of this FGF21 pathway in vivo.

In murine brain, there is evidence that FGF21 suppresses sweet preference through effects on the paraventricular nucleus in the hypothalamus (15). Among its actions in the hypothalamus, FGF21 induces corticotropin-releasing hormone (18, 19), which is a strong modulator of alcohol consumption (23). Notably, β-Klotho is also present in mesolimbic regions of the brain that regulate reward behavior, including the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens, and FGF21 administration reduced tissue levels of dopamine and its metabolites in the nucleus accumbens (14). Thus, FGF21 may act coordinately on multiple brain regions to regulate the consumption of both simple sugars and alcohol.

In closing, our data linking β-Klotho to alcohol consumption together with previous GWAS data linking FGF21 to macronutrient preference raise the intriguing possibility of a liver–brain endocrine axis that plays an important role in the regulation of complex adaptive behaviors, including alcohol drinking. Although our findings support an important role for the KLB gene in the regulation of alcohol drinking, we cannot rule out the possibility that KLB rs11940694 acts by affecting neighboring genes. Therefore, additional genetic and mechanistic studies are warranted. Finally, it will be important to follow-up on our findings in more severe forms of alcohol drinking, because our results suggest that this pathway could be targeted pharmacologically for reducing the desire for alcohol.

Methods

Alcohol Phenotypes.

Alcohol intake in grams of alcohol per day was estimated by each cohort based on information about drinking frequency and type of alcohol consumed. For cohorts that collected data in drinks per week, standard ethanol contents in different types of alcohol drinks were provided as guidance to convert the data to grams per week, which was further divided by seven to give intake as grams per day. Adjustment was made if cohort-specific drink sizes differed from the standard. For cohorts that collected alcohol use in grams of ethanol per week, the numbers were divided by seven directly into grams per day. Cohorts with only a categorical response to the question for drinks per week used midpoints of each category for the calculation. All nondrinkers (individuals reporting zero drinks per week) were removed from the analysis. The grams per day variable was then log10 transformed before the analysis. Sex-specific residuals were derived by regressing alcohol in log10 (grams per day) in a linear model on age, age2, weight, and if applicable, study site and principal components to account for population structure. The sex-specific residuals were pooled and used as the main phenotype for subsequent analyses.

Dichotomous alcohol phenotype was created based on categorization of the drinks per week variable. Heavy drinking was defined as ≥21 drinks per week in men or ≥14 drinks per week in women. Light (or zero) drinking was defined if male participants had ≤14 drinks per week or female participants had ≤7 drinks per week. Drinkers having >14 to <21 drinks for men or >7 to <14 drinks for women were excluded. Where information was available, current nondrinkers who were former drinkers of >14 drinks per week in men and >7 drinks per week in women as well as current nondrinkers who were former drinkers of unknown amount were excluded, whereas current nondrinkers who were former drinkers of ≤14 for men or ≤7 for women were included. Additional exclusion was made if there were missing data on alcohol consumption or the covariates.

The analyses only included participants of European origin and were performed in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Each cohort’s study protocol was reviewed and approved by their respective institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all study subjects.

Discovery GWAS in the Alcohol Genome-Wide Association (AlcGen) and Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Plus (CHARGE+) Consortia and Replication Analyses.

Genotyping methods are summarized in Dataset S1 B, C, and F. SNPs were excluded if the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P value was <1 × 10−6 or based on cohort-specific criteria, minor allele frequency (MAF) was <1%; imputation information score was <0.5; results were only available from two or fewer cohorts; or total n was <10,000. Population structure was accounted for within cohorts via principal components analysis. LD score regression (24) was conducted on the GWAS summary results to examine the degree of inflation in test statistics, and genomic control correction was considered unnecessary (λGC = 1.06 and intercept = 1.00; λ=0.99–1.06 for individual cohorts) (Dataset S1 B and C). SNPs were taken forward for replication from discovery GWASs if they passed the above criteria and had P < 1 × 10−6 [one SNP with the smallest P taken forward in each region, except for AUTS2, for which two SNPs were taken forward based on previous results (7)]. Metaanalyses were performed by METAL (25) or R (v3.2.2).

Gene Expression Profiling in the Framingham Heart Study.

In the Framingham Heart Study, gene expression profiling was undertaken for the blood samples of a total of 5,626 participants from the offspring cohort (n = 2,446) at examination 8 and the third generation cohort (n = 3,180) at examination 2. Fasting peripheral whole-blood samples (2.5 mL) were collected in PAXgene Tubes (PreAnalytiX). RNA expression profiling was conducted using the Affymetrix Human Exon Array ST 1.0 (Affymetrix, Inc.) for samples that passed RNA quality control. The expression values for ∼18,000 transcripts were obtained from the total 1.2 million core probe sets. Quality control procedures for transcripts have been described previously.

The cis-Expression Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis in the Framingham Heart Study.

To investigate possible effects of rs11940694 in KLB on gene expression, we performed cis-expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis. The SNP in KLB was used as the independent variable in association analysis with the transcript of KLB measured using whole-blood samples in the Framingham Heart Study (n = 5,236). Affymetrix Probe 2724308 was used to represent the KLB overall transcript levels. Age, sex, body mass index, batch effects, and blood cell differentials were included as covariates in the association analysis. Linear mixed model was used to account for familial correlation in association analysis.

Mouse Studies.

All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Male littermates (2–4 mo old) maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to chow diet (Harlan Teklad TD2916) were used for all experiments. The Klb gene was deleted from brain by crossing Klbfl/fl mice with Camk2a-Cre mice on a mixed C57BL/6J;129/Sv background as described (26).

Alcohol Drinking in Mice.

For voluntary two-bottle preference experiments, male mice (n = 9–13 per group) were given access to two bottles: one containing water and the other containing 2–16% (vol/vol) ethanol in water. After acclimation to the two-bottle paradigm, mice were exposed to each concentration of ethanol for 4 d. Total fluid intake (water and ethanol-containing water), food intake, and body weight were measured each day. Alcohol consumption (grams) was calculated based on EtOH density (0.789 g/mL). To obtain accurate alcohol intake that corrected for individual differences in littermate size, alcohol consumption was normalized by body weight per day for each mouse. As a measure of relative alcohol preference, the preference ratio was calculated at each alcohol concentration by dividing total consumed alcohol solution (milliliters) by total fluid volume. Two-bottle preference assays were also performed with sucrose [0.5 and 5% (wt/vol)] and quinine (2 and 20 mg/dL) solutions. For all experiments, the positions of the two bottles were changed every 2 d to exclude position effects.

Mouse Experiments with FGF21.

For FGF21 administration studies, recombinant human FGF21 protein provided by Novo Nordisk was administered at a dose of 0.7 mg/kg per day by s.c. osmotic minipumps (Alzet 1004). Mice were single caged after minipump surgery, which was conducted under isoflurane anesthesia and 24 h of buprenorphine analgesia. Mice were allowed to recover from minipump surgery for 4 d before alcohol drinking tests. After experiments, mice were killed by decapitation, and plasma was collected using EDTA or heparin after centrifugation for 15 min at 4,697 × g. Plasma FGF21 concentrations were measured using the Biovendor FGF21 ELISA Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Plasma Ethanol Concentration and Clearance.

For alcohol bioavailability tests, mice (n = 4–5 per group) were injected i.p. with alcohol (2.0 g/kg; 20% wt/vol) in saline, and tail vein blood was collected after 1 and 3 h. Plasma alcohol concentrations were measured using the EnzyChrom Ethanol Assay Kit.

Emotional Behavior in Mice.

For open-field activity assays, naïve mice were placed in an open arena (44 × 44 cm, with the center defined as the middle 14 × 14 cm and the periphery defined as the area 5 cm from the wall), and the amount of time spent in the center vs. along the walls and total distance traveled were measured. For elevated plus maze activity assays, mice were placed in the center of a plus maze with two dark enclosed arms and two open arms. Mice were allowed to move freely around the maze, and the total duration of time in each arm and the frequencies of entering both the closed and open arms were measured. For novelty suppression of feeding assays, mice fasted for 12 h were placed in a novel environment, and the time to approach and eat a known food was measured.

Statistical Analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis between the two groups was performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test using Excel or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey was done using SPSS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources and acknowledgments for contributing authors and consortia can be found in SI Appendix. Part of this work used computing resources provided by Medical Research Council-funded UK Medical Bioinformatics Partnership Programme MR/L01632X/1.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: B. Psaty serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for a clinical trial funded by the manufacturer (Zoll LifeCor) and the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access project funded by Johnson & Johnson. D.J.M. serves on the scientific advisory board of Metacrine. The other authors report no competing financial interests.

Data deposition: The database information reported in this paper has been supplied in Datasets S1 and S2. The gene expression profiling data from the Framingham study used herein are available online in dbGaP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap; accession no. phs000007). The full meta-analysis data for the continuous and dichotomous alcohol consumption traits are available online at the dbGaP CHARGE Summary site (accession no. phs000930).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1611243113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anonymous . Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. WHO; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6279):1847–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hines LM, Rimm EB. Moderate alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease: A review. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77(914):747–752. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.914.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heath AC, Meyer J, Eaves LJ, Martin NG. The inheritance of alcohol consumption patterns in a general population twin sample. I. Multidimensional scaling of quantity/frequency data. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52(4):345–352. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierut LJ, et al. ADH1B is associated with alcohol dependence and alcohol consumption in populations of European and African ancestry. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(4):445–450. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumann G, et al. Genome-wide association and genetic functional studies identify autism susceptibility candidate 2 gene (AUTS2) in the regulation of alcohol consumption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(17):7119–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017288108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen BM, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Tissue-specific actions of the metabolic hormones FGF15/19 and FGF21. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dushay JR, et al. Fructose ingestion acutely stimulates circulating FGF21 levels in humans. Mol Metab. 2014;4(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez J, Palou A, Picó C. Response to carbohydrate and fat refeeding in the expression of genes involved in nutrient partitioning and metabolism: Striking effects on fibroblast growth factor-21 induction. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5341–5350. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, et al. FGF21 mediates alcohol-induced adipose tissue lipolysis by activation of systemic release of catecholamine in mice. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(8):1481–1491. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M058610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu AY, et al. CHARGE Nutrition Working Group DietGen Consortium Novel locus including FGF21 is associated with dietary macronutrient intake. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(9):1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talukdar S, et al. FGF21 Regulates Sweet and Alcohol Preference. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Holstein-Rathlou S, et al. FGF21 mediates endocrine control of simple sugar intake and sweet taste preference by the liver. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splansky GL, et al. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study: Design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(11):1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller CP, Schumann G. Drugs as instruments: A new framework for non-addictive psychoactive drug use. Behav Brain Sci. 2011;34(6):293–310. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Q, et al. FGF21 maintains glucose homeostasis by mediating the cross talk between liver and brain during prolonged fasting. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4064–4075. doi: 10.2337/db14-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen BM, et al. FGF21 acts centrally to induce sympathetic nerve activity, energy expenditure, and weight loss. Cell Metab. 2014;20(4):670–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douris N, et al. Central fibroblast growth factor 21 browns white fat via sympathetic action in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156(7):2470–2481. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iizuka K, Takeda J, Horikawa Y. Glucose induces FGF21 mRNA expression through ChREBP activation in rat hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(17):2882–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uebanso T, et al. Paradoxical regulation of human FGF21 by both fasting and feeding signals: Is FGF21 a nutritional adaptation factor? PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilig M, Koob GF. A key role for corticotropin-releasing factor in alcohol dependence. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(8):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulik-Sullivan BK, et al. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):291–295. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: Fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bookout AL, et al. FGF21 regulates metabolism and circadian behavior by acting on the nervous system. Nat Med. 2013;19(9):1147–1152. doi: 10.1038/nm.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.