Abstract

The transcription factor E2A can promote precursor B cell expansion, promote G1 cell cycle progression, and induce the expressions of multiple G1-phase cyclins. To better understand the mechanism by which E2A induces these cyclins, we characterized the relationship between E2A and the cyclin D3 gene promoter. E2A transactivated the 1-kb promoter of cyclin D3, which contains two E boxes. However, deletion of the E boxes did not disrupt the transactivation by E2A, raising the possibility of indirect activation via another transcription factor or binding of E2A to non-E-box DNA elements. To distinguish between these two possibilities, promoter occupancy was examined using the DamID approach. A fusion construct composed of E2A and the Escherichia coli DNA adenosine methyltransferase (E47Dam) was subcloned in lentivirus vectors and used to transduce precursor B-cell and myeloid progenitor cell lines. In both cell types, specific adenosine methylation was identified at the cyclin D3 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis confirmed the DamID findings and localized the binding to within 1 kb of the two E boxes. The methylation by E47Dam was not disrupted by mutations in the E2A portion that block DNA binding. We conclude that E2A can be recruited to the cyclin D3 promoter independently of E boxes or E2A DNA binding activity.

E2A is essential to normal B-cell development. B cells, even at the earliest detectable precursor-B-cell developmental stage, do not develop in mice that lack E2A (2, 68). Heterozygote murine fetuses that express only one copy of E2A have half the number of B cells, suggesting that the level of E2A may dictate the number of B cells (68). E2A function is intrinsic to B cells, since transfer of E2A null bone marrow cells into wild-type mice fails to rescue B-cell development while ectopic expression of E2A in E2A null mice rescues B-cell development (67).

E2A is frequently mutated in precursor-B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common neoplasm in childhood (65). Approximately 6% of pediatric ALLs have chromosomal translocations involving the E2A gene (29). These translocations represent the second-most-frequent translocation in ALL and are almost always associated with ALL of precursor-B-cell origin. The most common E2A translocation, t(1;19), is associated with poor response to older standard risk ALL therapies. Even with the current ALL therapies, the t(1:19) translocation is sufficient to decrease the prognosis from low risk (>90% 4-year event-free survival) to standard risk (approximately 80% 4-year event-free survival).

Normal E2A regulates cell cycle progression, an important contributor of cell accumulation that is frequently disrupted during carcinogenesis. Hence, mutations in E2A may contribute to abnormal B-cell accumulation by disrupting normal regulation of cell cycle progression by E2A. The nature of this regulation is unclear. Numerous studies support the current model that E2A inhibits cell cycle progression (19, 40, 41). However, other studies are inconsistent with the current model and demonstrate that E2A does not inhibit and can even promote cell cycle progression (12, 24, 39, 66). E2A is a transcription factor and most likely functions by inducing the expression of its target genes. Identification of E2A target genes and understanding the mechanism of their induction by E2A are increasing our understanding of the normal function of E2A and its role in leukemogenesis.

One group of candidate target genes inhibits G1 progression and includes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs) p21, INK4A, and INK4B. CDKIs are induced by E2A in 293T cells (39, 42). In non-B cells, p21, INK4A, and INK4B are each capable of arresting G1 progression (8, 35, 44, 59). The regulation of the CDKIs appears dependent on the E boxes in their promoter regions.

We have identified another group of candidate target genes that promotes G1 progression and that includes the G1-phase cyclins cyclin D3, cyclin D2, and cyclin A (66). Each of the three cyclins can promote G1 progression in fibroblasts, T-cell lines, or myeloid cell lines (1, 3, 5, 23, 26, 38, 43). The mechanism of regulation of these genes by E2A is not known, but we hypothesize that E2A induces the expression of these cyclins via the multiple E boxes present in the promoters. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by characterizing the relationship between E2A and cyclin D3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The plasmids pMD-VSV-G and delta 8.2 (34), SV/E2-5 (10), and (523)4 luciferase reporter (7) have been previously described (66). The TK-Renilla luciferase plasmid was purchased from Promega (Madison, Wis.). The cyclin D3 and delta D3 luciferase reporter plasmids were engineered by replacing the artificial E-box enhancer of the (523)4 luciferase reporter with a PCR-amplified portion of the cyclin D3 promoter/enhancer region. The bp −1 to −1017 portion (D3) was amplified from K562 genomic DNA, using the primers 5′-AGATCTCACAGAGTCTGTGCAAGAAAC-3′ and 5′-TCGAACGGGGCAGCGAAAGGCAGGGC-3′. The bp −1 to −608 bp portion (delta D3) was amplified using the primers 5′-AGATCTCACAGAGTCTGTGCAAGAAAC-3′ and 5′-AGATCTCCTCGGTTTCCGAGTTTTCGT-3′. The dam construct (57) was generously provided by Bas van Steensel (Netherlands Cancer Institute). The dam insert was ligated in frame to the E47 splice form of E2A to generate the fusion construct E47Dam. Dam and E47Dam were subcloned into the multicloning site of a lentivirus vector that weakly expresses its transgene off the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat. This vector was engineered by deleting the internal cytomegalovirus promoter/enhancer of pHR′CMVGFP (9) using standard cloning techniques. E47Dam was mutated to E47Dam(9,15) by site-directed mutagenesis. using the primers 5′-GGACCGGGAGGGAGGCATGGCCAATAACG-3′, 5′-CGTTATTGGCCATGCCTCCCTCCCGGTCC, 5′-CGCGGGAGCGGGTGAAGGTGCGGGATATTAAC-3′, and 5′-GTTAATATCCCGCACCTTCACCCGCTCCCGCG-3′.

Tissue culture and cells.

K562, K562E47R, Nalm6, and 293T cells were cultured in RPMI or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in 5% CO2, as previously described (66). Tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was used at a concentration of 1 uM.

Luciferase assay.

293T cells were transiently transfected using calcium phosphate precipitate as previously described (66). K562 cells were transiently lipofected using 1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-3-dimethyl-hydroxy ethyl ammonium bromide and cholesterol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) following the manufacture's protocol. Briefly, 0.5 ml of Opti-MEM medium, 12 μl of 1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-3-dimethyl-hydroxy ethyl ammonium bromide and cholesterol, and 4 μg of total DNA were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and added to 2 million cells. After 5 h, 2 ml of 10% RPMI medium were added. The cells were harvested 2 days posttransfection and analyzed using the Dual Luciferase Assay kit from Promega (Madison, Wis.) following the manufacturer's protocol. All luciferase assays were performed at least three times in duplicate.

DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA purification columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.), using the manufacturer's protocol. DNA was quantified by UV absorption spectrophotometry and by ethidium bromide binding.

PCR.

Five nanograms of genomic DNA was amplified in 50 μl for 30 cycles using 0.5 U of Amplitaq Gold (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.), 0.5 uM (each) primer, and PCR parameters that consisted of denaturing at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and elongating at 72°C for 30 s.

LM-PCR.

Adenosine-methylated genomic DNA was identified by combining procedures for DamID and representation difference analysis (28). Two micrograms of genomic DNA were cut with DpnI and blunt-end ligated to a linker oligonucleotide by using T4 DNA ligase. Nested PCR was performed by amplifying 0.2 μg of linker-ligated genomic DNA for 20 cycles with an outer genomic specific primer and LMP-T0. LMP-T0 hybridizes to the outer portion of the linker oligonucleotide. One-tenth of the resulting reaction was amplified for another 20 cycles using an inner genomic specific primer and LMP-T2. LMP-T2 hybridizes to the inner portion of the linker oligonucleotide and to the half-DpnI site of the DpnI-cut genome. The requirement for the half-DpnI site decreases the amplification of linker oligonucleotides ligated to randomly sheared genomic DNA. In some cases, ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) was performed using a TaqMan-based quantitative PCR (qLM-PCR), GeneAmp 5700, 0.2 μg of linker-ligated genomic DNA, inner genomic specific primer, LMP-T2, and a TaqMan probe with 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein and 3′-6-carboxy-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylrhodamine. The data were analyzed by using the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. The sequences of the oligonucleotides are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used for linker ligation, PCR, nested LM-PCR, and qLM-PCR

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence(s) |

|---|---|

| Linker primers | |

| Linker oligonucleotide | GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC, GAATTCAGATC |

| LMP-T0 | GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGA |

| LMP-T2 | GTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTCTC |

| PCR primer sets | |

| IgH enhancer | GGATCCGGCCCCGATGCGGGACTGCG, ATTCTGATAGAGTGGCCTTCAGGATCC |

| D3+5K | AGCTCACAGAGCTGCTGGCAG, GGCAAGAAAAGAACCCCTAGG |

| D3+10k | CCCTTTCTTCCGTGCCTCTGG, ACTGTCGTGTGAGTTGGAAAC |

| HPRT | CTGCTTCTCCTCAGCTTCA, GACGTAAAGCCGAACCCGGGAAACT |

| GAPDH | CAGTCCTGGGAACCAGCACCG, GTCTTCACCTGGCAGCGCAAA |

| Nested LM-PCRa | |

| IgH enhancer | TTTAAAAATGAATGCAGTTTAGAA, CAGTTTAGAAGTTGATATGCTGTTTGC |

| D3+0K LM-PCR | CACAGAGTCTGTGCAAGAAAC, CCTCGGTTTCCGAGTTTTCGT |

| D3+5K LM-PCR | GGCAAGAAAAGAACCCCTAGG, CAGTGCCCTTCACCCCAGCCAAGATAC |

| D3+10K LM-PCR | ACTGTCGTGTGAGTTGGAAAC, CCCCCGCTTAACTCCCACTAGGATTTT |

| HPRT | CTGCTTCTCCTCAGCTTCA, GCCCTCAGGCGAACCTCTCGGCTTT |

| GAPDH | GTCTTCACCTGGCAGCGCAAA, AGAAGATGCGGCTGACTGTCGAACAGG |

| qLM-PCRb | |

| D3+0K | AATGCAGATTCTGATTCAGGTTAGG, CCTGAGAGTCTGCATTTCTAACCAGC |

| D3+5K | AGGCTCAGGGCATAGCACTACT, CTGGGCAGCAGCCTCTCCATTCA |

| D3+10K | CAAGAAGGCCCTTTTCAAACC, ATTCTCCCACCTTTGAACCAGGC |

| CD19 | TGCCACGCTGTTTTATTTTCAT, TCATTTCCCGTGGTAGTGAGAGCTGG |

| IgH enhancer | TCAGCCTCGCCTTATTTTAGAAA, TCTACTGAGCAAAACAACACCTGGACAATTTG |

First sequence is that of outer primer used with LMP-T0; second sequence is that of inner primer used with LMP-T2.

First sequence is that of primer used with LMP-T2; second is that of TaqMan probe.

Positive controls for LM-PCR and qLM-PCR were generated by PCR amplifying K562 genomic DNA, subcloning the PCR product, and amplifying the plasmids in the Dam+ DH5α Escherichia coli. The methylated plasmids were isolated by CsCl gradient, sequence verified, and used as methylated positive controls.

Generation of virus and transduction.

Retroviruses were generated as previously described (9). Briefly, lentivirus vector, expression plasmid for vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein, and helper plasmid delta 8.2 were transiently cotransfected by calcium precipitate into 293T cells, and the culture medium was harvested 48 to 72 h posttransfection. Cells were transduced by spinoculation using 1 million cells, 1 ml of virus supernatant, and 8 μg of polybrene (Sigma)/ml.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression was detected on a FACSTAR, and the data were analyzed using Cell-Quest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) as previously described (66).

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting was performed as previously described (66), using antibodies to E47 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) and estrogen receptor (Ab-11, Lab Vision Corporation, Fremont, Calif.). Briefly, cells were lysed in 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 60 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Protein was quantified using a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Twenty micrograms of protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose by electroblotting.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis (ChIP).

Assays were performed as described previously (15). Briefly, 108 cells were cross-linked in 0.4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 0.125 M glycine. Chromatin was fragmented by sonication to an average size of 500 bp, precleared with irrelevant antibodies, and immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of the anti-estrogen receptor antibody or 10 μg of control mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) prebound to protein G beads. After seven washes, bound proteins were eluted with 100 mM NaHCO3-1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Cross-links were reversed at 65°C for 4 h and protein was digested with proteinase K (0.3 mg/ml) for 2 h at 45°C. DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR (SYBR Green; Applied Biosystems). To normalize for slight variations in chromatin preparations, a standard curve of nonimmunoprecipitated DNA and immunoprecipitated chromatin was compared to this standard. Primer sequences were as follows: −0.3 K, AGTTTCTCCGTCCACAGTTTCTCC, CATGGCCTCACCTTGTTAAGTTGC; E boxes, AGCAAGAAGGCCAGCTTCCCAAT and AAACTCGGAAACCGAGGCAACTGT; +1 K, TTGCTTTCCCGAGCCCTAATCG and AGAGAGTGTCCTTGGTCCCGTTT; +5 K, TAAAGTAGTGCTATGCCCTGAGCC and CCAAGGTTGTGAAACCAGGACTTG; +10 K, TTCAGCAACGTCATCTCG and TTTGCCTCTAACCTGAAGGAACGC; and IgH intronic enhancer, TCACTTCTGGTTGTGAAGAGGTGG and GTTTCGGTCAGCCTCGCCTTATTT.

RESULTS

Transactivation of the cyclin D3 promoter by E2A.

We have previously shown that cyclin D3 transcript and protein levels are induced by E2A in hematopoietic cells; furthermore, the increased transcript expression does not require new protein synthesis, suggesting that cyclin D3 is a direct target of E2A (66). To better characterize the mechanism by which E2A induces cyclin D3, we examined the promoter region of the cyclin D3. The human cyclin D3 promoter has been characterized in proliferating vascular smooth muscle (6). In these cells, the sequences 1 to 1,017 bp upstream of the cyclin D3 transcription start point conferred constitutive activity in a luciferase reporter plasmid. We hypothesized that the 1-kb cyclin D3 promoter is responsible for the E2A-mediated induction of cyclin D3 transcripts. To test this, the 1,017 bp of the cyclin D3 promoter/enhancer (D3) were PCR amplified from human genomic DNA, verified by sequencing, and subcloned into a luciferase reporter plasmid (Fig. 1A).

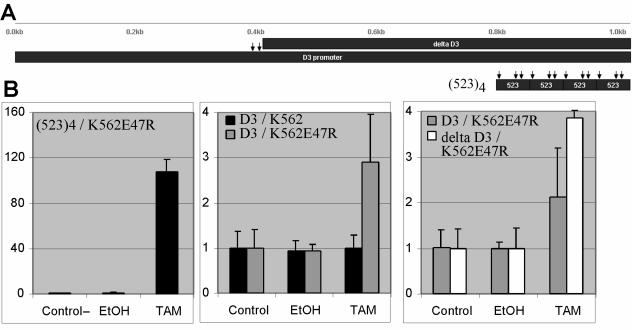

FIG. 1.

E2A transactivates the cyclin D3 promoter, independently of the E boxes. (A) Representation of the 1,017-bp and 614 upstream regions of cyclin D3 (D3 and delta D3) and the artificial multimerized E boxes from the IgH intronic enhancer [(523)4]. Arrows point to the E boxes. (B) K562E47R cells with tamoxifen-inducible E2A activity were lipofected with (523)4, D3, or delta D3 reporter plasmid, treated with ethanol (EtOH) or tamoxifen (TAM), and assayed by dual-luciferase assay. D3 reporter plasmid was also analyzed in K562 cells without E2A activity. The y axis represents n-fold activation after normalization for cotransfected Renilla luciferase activity.

The D3 reporter was analyzed in the K562E47R cells that we have described previously (66). K562E47R is a stable line of the progenitor myeloid cell K562 that expresses E47R, a fusion protein of E47 (a major transcript of E2A) and the hormone-binding domain of the estrogen receptor. The activity of E47R is induced by the small molecule tamoxifen. This cell line has the advantages of little to no basal level of E2A activity and can be readily transfected, two features currently lacking in human precursor-B-cell lines. To confirm that E2A activity is induced with tamoxifen in K562E47R cells, these cells were studied by transient-transfection assays by using an artificial (523)4 reporter plasmid that contains multiple E boxes upstream of the luciferase gene (Fig. 1A). The (523)4 luciferase reporter is specific for active homodimers of E47 that are restricted to B cells or to non-B cells expressing ectopic E47 (47, 50, 61). Transfected cells were split into control and sample wells, insuring equal transfection between control and sample wells. The transfected cells were treated with 10−6 M tamoxifen or 0.1% ethanol for 2 days and analyzed by dual-luciferase assay with the luciferase activities normalized to cotransfected Renilla luciferase activities (Fig. 1B). Without tamoxifen, the reporter activity was near background levels, indicating low to absent basal activity of E47R. With tamoxifen, luciferase activity increased more than 70-fold, demonstrating that K562E47R cells have inducible E2A activity. In contrast, tamoxifen did not induce E2A activity in the parental K562 cells (data not shown).

Next, the K562E47R cells were transiently transfected with the D3 reporter plasmid, treated with tamoxifen, and analyzed by dual-luciferase assay. The reporter activity increased with tamoxifen (Fig. 1B, middle panel). In contrast, no increase was seen in control K562E47R cells without tamoxifen and in parental K562 cells with tamoxifen treatment. These findings indicated the presence of E2A-responsive elements within the cyclin D3 gene.

The cyclin D3 promoter/enhancer contains two E boxes at positions −624 and −614 relative to the transcriptional start site. To determine the importance of these sites to transactivation by E2A, the sequences 1 to 608 bp upstream of the cyclin D3 transcription start point were PCR amplified (delta D3), verified by sequencing, and subcloned into a luciferase reporter plasmid (Fig. 1A). This delta D3 reporter was analyzed by dual-luciferase assay in K562E47R cells. Despite the lack of E boxes in the delta D3 reporter, luciferase activity was induced to an extent similar to that seen in the D3 reporter (Fig. 1B, right panel).

In vivo occupancy of the cyclin D3 promoter by E2A.

The transactivation of the delta D3 reporter by E2A suggests that either E2A interacts with cryptic sites in the cyclin D3 promoter that do not have the consensus E-box sequences or E2A induces cyclin D3 indirectly via induction of another transcription factor. To differentiate between these possibilities, we examined whether E2A binds the chromatin-embedded cyclin D3 gene, using the DamID technique. In this technique, a fusion protein composed of a DNA binding protein and the E. coli DNA adenosine methyltransferase (Dam) is engineered and expressed in cells (57). High expression of Dam methylates 50% of all GATC sites (62), but at low expression, the Dam portion of the fusion protein methylates GATC sites within 2 to 5 kb of the DNA sites recognized by the DNA binding portion. Within 4 to 10 kb of DNA that flanks a binding site, 15 to 39 GATC sites would be expected. The methylated but not the unmethylated GATC sequence is recognized by the endonuclease DpnI. This approach has the advantage of a low background because endogenous Dam activity is absent in eukaryotic cells.

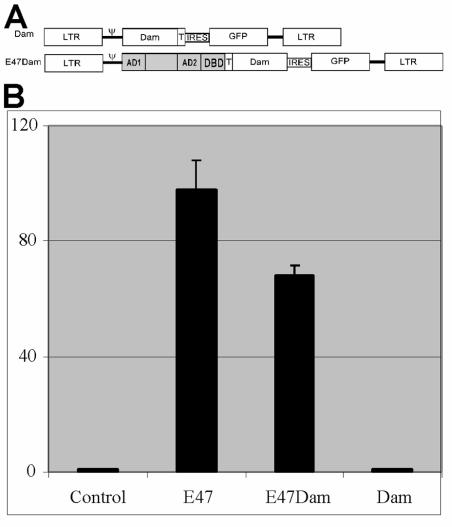

The Dam construct was ligated in frame to the E47 splice form of E2A to generate the fusion transcript E47Dam. Both E47Dam and control Dam constructs were subcloned into a lentiviral vector that lacks strong enhancers/promoters (Fig. 2A) and thus weakly expresses its transgene. The construct was analyzed to determine if E47 and Dam activities were preserved in the E47Dam fusion protein. E47Dam transactivated the (523)4 luciferase reporter in a transient-transfection assay, indicating that the E2A activity and thus the DNA binding activity were preserved in the fusion protein (Fig. 2B). The Dam methylase activity of E47Dam was measured using a ligation-mediated PCR assay (LM-PCR).

FIG. 2.

Lentivirus E47Dam fusion construct retains E2A activity. (A) Representation of E47Dam and Dam constructs. LTR, long terminal repeats; ψ, viral packaging signal; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; GFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; AD1, AD2, and DBD, transcription activation domains 1 and 2, and DNA binding domain of E47, respectively; Dam, DNA adenosine methyltransferase; T, c-myc tag. (B) 293T cells were transfected with (523)4 plasmid reporter and E47, E47Dam, or Dam and then analyzed by dual-luciferase assay.

Since LM-PCR for DamID has not been reported, we detail the specificity and sensitivity of this assay. A 661-bp IgH intronic enhancer, a known direct target gene of E2A (17), was PCR amplified and used as an unmethylated negative control. The same sequence was subcloned into a plasmid and amplified in Dam+ E. coli. The Dam-modified insert was isolated and used as a methylated positive control. The PCR product and plasmid insert were cut with DpnI, blunt end ligated to linker oligonucleotides, PCR amplified, and analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3A). The methylated insert but not the unmethylated PCR product was cut by DpnI (upper gel) and was amplified using primers that hybridize to IgH and to the ligated linker oligonucleotides (middle gel). Unmethylated and hence uncut IgH enhancer was PCR amplified by using primers for the original 661-bp IgH enhancer (lower gel). A PCR product was seen even in the DpnI-cut positive control (rightmost lane), probably representing incomplete DpnI cutting of the methylated plasmid insert.

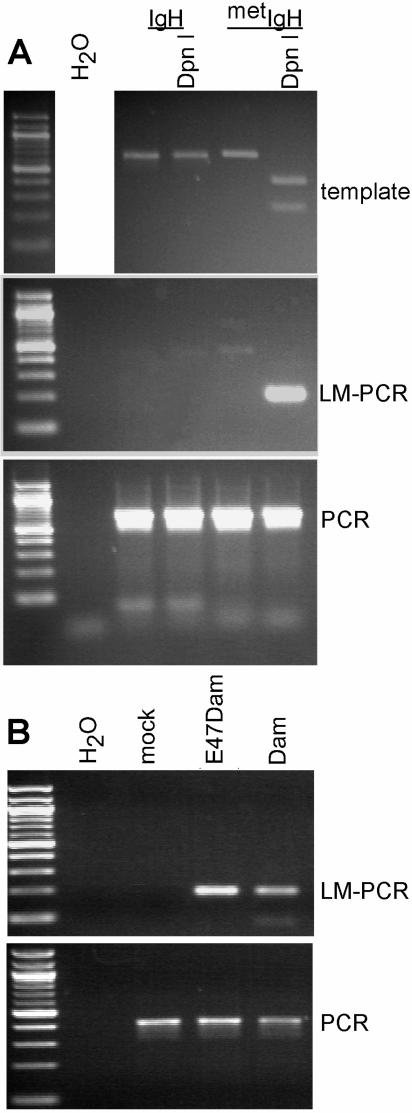

FIG. 3.

The LM-PCR assay is a specific and sensitive assay for adenosine-methylated DpnI sites. (A) Cloned IgH enhancer and adenosine-methylated IgH (metIgH) inserts were cut with DpnI and then analyzed by LM-PCR or PCR using primers for the IgH enhancer. The DpnI-cut inserts, LM-PCR products, and PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (top, middle, and bottom panels, respectively). (B). E47Dam and Dam were expressed in 293T by transient transfection, and their genomic DNA was analyzed by PCR and LM-PCR assays for the IgH enhancer.

To demonstrate the methylase activities of the Dam and E47Dam constructs, they were transiently transfected into the human embryonic kidney cell line 293T, which expresses transfected expression constructs at high levels. LM-PCR analysis of the genomic DNA demonstrated that both constructs methylated the IgH enhancer locus (Fig. 3B), an expected finding since high expression of Dam methylates most Dam sequences (62). These findings demonstrate that the Dam portion of E47Dam is active, human 293T cells have no endogenous adenosine methylase activity similar to that of other eukaryotic cells (25, 62), and the LM-PCR assay is highly specific for Dam-methylated sites.

The sensitivity of the LM-PCR assay was determined by spiking human genomic DNA with the positive control IgH enhancer plasmid at 0.0, 0.063, 0.13, 0.25, 0.50, and 1.00 copies per cell. If both alleles in a cell are methylated by E47Dam, then these copy numbers represent methylation in 0, 3.2, 6.5, 13, 25, and 50% of the cells. The spiked DNA was cut with DpnI, ligated with linker oligonucleotides, and PCR amplified using seminested primers. The LM-PCR assay detected methylation in as few as 3.2% of the cells (Fig. 4B), a percentage of cells that is routinely transduced with our lentivirus vectors, thus allowing direct analysis of the transduced cells without selection.

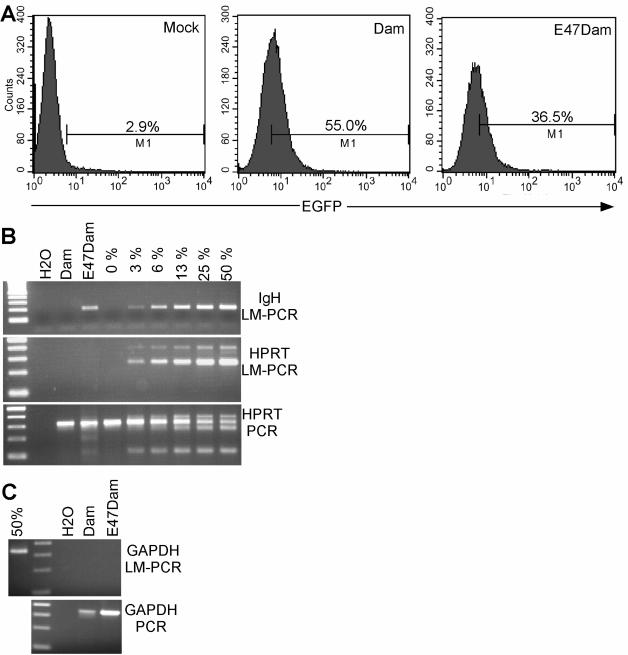

FIG. 4.

E47Dam but not Dam methylates the endogenous IgH loci, an E2A target site. (A) The precursor B-cell line Nalm6 was transduced with lentiviruses that weakly coexpress EGFP and Dam or E47Dam. After 6 days, the cells were analyzed for EGFP expression using flow cytometry. (B and C) Genomic DNAs were isolated from the transduced cells and analyzed by LM-PCR for IgH enhancer, HPRT promoter, and GAPDH promoter. A semiquantitative standard curve was generated using Nalm6 genomic DNA that was spiked with 0 to 50% methylated IgH enhancer or HPRT promoter insert. For GAPDH, only the DNA spiked with 50% methylated GAPDH promoter was analyzed as a positive control. Fifty percent represented the addition of methylated enhancer/promoter that would be equivalent to 50% of the endogenous enhancer/promoter in the genomic DNA sample. The genomic DNA that was cut with DpnI and ligated to linker oligonucleotides was also analyzed by PCR for HPRT promoter or GAPDH sequences.

Lentiviruses that weakly express E47Dam or Dam were used to transduce Nalm6 cells. Nalm6 cells were chosen for this analysis because they are precursor B cells that express active E2A and likely have E2A target genes in open chromatin configuration, allowing ready access for the transduced Dam constructs. Flow cytometry for EGFP demonstrated that approximately 35 to 55% of the cells were transduced with E47Dam and Dam (Fig. 4A). The purposely low level of expression of EGFP with fluorescent overlap of EGFP− and EGFP+ cells precludes accurate assessment of the percentage of transduced cells. Seven days posttransduction, the genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed by LM-PCR using specific primers against the IgH intronic enhancer. LM-PCR analysis showed methylation of the endogenous IgH intronic enhancer locus with E47Dam but not with Dam (Fig. 4B). In contrast, E47Dam did not methylate the promoter of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), a known nontarget of E2A (56). Regular PCR amplification of the HPRT promoter, post-DpnI digestion, and linker oligonucleotide ligation demonstrated equal amounts of product among the E47Dam- and Dam-modified genomic DNA. Similar findings were seen with another nontarget of E2A, the promoter region of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Fig. 4C). Additional PCR bands were seen in samples spiked with a higher concentration of methylated HPRT and most likely represented competitive PCR between unmethylated and methylated HPRT. The additional bands were not seen if PCR amplification was performed prior to DpnI digestion and linker oligonucleotide ligation (data not shown). These findings indicate that the E47 portion of E47Dam directed the Dam portion to E2A binding sites. Identical findings were seen when another precursor-B-cell line, 697, was transduced with E47Dam or Dam (data not shown).

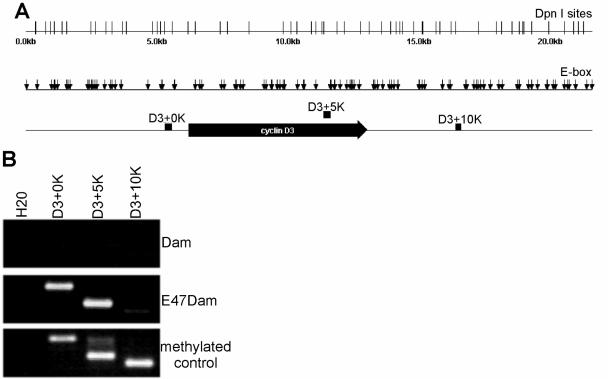

The same genomic DNA was then analyzed by LM-PCR using primers for the cyclin D3 gene that amplified sequences at 0 kb (D3+0K), 5 kb (D3+5K), and 10 kb (D3+10K) downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 5A). E47Dam methylated at D3+0K and D3+5K but only very weakly at D3+10K, suggesting that E47 bound around D3+0K or D3+5K or both (Fig. 5B). DNA binding/Dam fusion proteins can adenosine methylate as far as 5 kb from the binding site, but the degree of methylation decreases with increased distance (57). Since the methylation decreased with increased distance from the binding site, quantification of the methylation should identify the binding site within 5 kb. For example, if methylation at D3+0K was greater than that at D3+5K, then E47 likely bound around the promoter of cyclin D3, with methylation of 5K as a bystander effect.

FIG. 5.

E47Dam methylates the cyclin D3 gene. (A) Representation of the 23-kb genome sequences that encompass the cyclin D3 gene with predicted DpnI sites (vertical line) and E boxes (small vertical arrow). The large horizontal arrow indicates the transcribed portion of the cyclin D3 gene. D3+0K, D3+5K, and D3+10K are sequences amplified by LM-PCR primers that hybridize to sequences 0, 5, and 10 kb downstream of the cyclin D3 promoter. (B) Genomic DNAs were isolated from cells transduced with Dam or E47Dam and then analyzed by LM-PCR. Methylated controls were Nalm6 genomic DNA spiked with methylated cyclin D3 inserts that encompassed the sequences 0, 5, and 10 kb downstream of the cyclin D3 promoter. The added methylated inserts represented approximately 50% of the endogenous sequences.

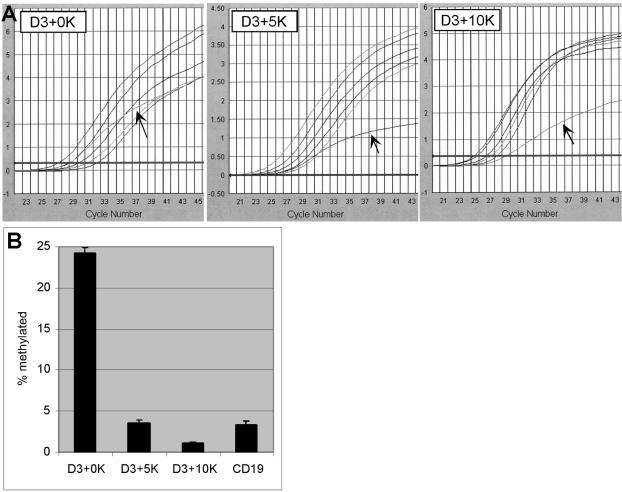

To more accurately measure the methylation of the genomic DNA, real-time or quantitative LM-PCR (qLM-PCR) was used to analyze methylation at the cyclin D3 locus (Fig. 6). Standard curves for different percentages of methylation at D3+0K, D3+5K, and D3+10K sequences were generated by spiking known amounts of methylated sequences to genomic DNA. The spiked DNA was cut with DpnI, ligated with linker oligonucleotides, and analyzed by real-time PCR. The percentage of methylated sequence at the D3+0K by real-time PCR (24%) correlated well with the expected percentage based on the percentage of cells that expressed E47Dam by flow cytometry (35%). The methylations at D3+5K and D3+10K were approximately 4 and 1%, respectively. The highest level of methylation occurred at the D3+0K sequences, suggesting that the E2A binding site is likely at this site or further upstream. Furthermore, the methylation at the promoter of CD19, a known non-target gene of E2A (17), was approximately 3% (Fig. 6B), supporting the premise that E47Dam selectively methylates E2A binding sites and cyclin D3 is a direct target gene of E2A.

FIG. 6.

E47Dam methylates the cyclin D3 promoter preferentially over more distal sites and the CD19 promoter. (A) Genomic DNAs isolated from E47Dam-transduced Nalm6 cells were analyzed using a TaqMan-based qLM-PCR. The y axis represents fluorescent signal intensity. Arrows point to the kinetic curves from E47Dam-transduced cells. The remaining five curves represent Nalm6 genomic DNA spiked with 3, 6, 13, 25, and 50% methylated inserts that were used to generate a standard curve. (B) The standard curves were used to estimate the percentages of methylation at different genomic loci. CD19, LM-PCR analysis of the promoter regions of CD19, a known B-cell-specific gene that is not regulated by E2A.

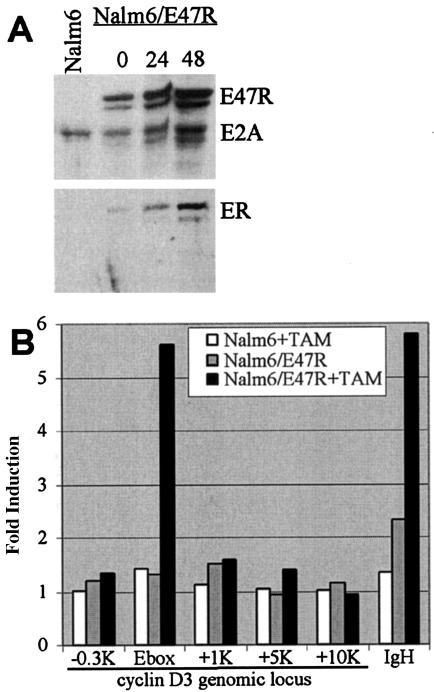

The direct binding of E2A to the cyclin D3 promoter was independently confirmed by ChIP using a monoclonal antibody against the estrogen receptor portion of E47R. In contrast to DamID analysis, ChIP requires uniform expression of E2A at sufficient levels to compete with the endogenous E2A for the target sites. To fulfill these criteria, we transduced Nalm6 cells with a high-expression E47R lentivirus vector and isolated the transduced cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting for green fluorescent protein-positive cells. The resulting stable cell line (Nalm6/E47R) was analyzed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). Nalm6/E47R cells expressed E47R to levels similar to those with the endogenous E2A. The antibody against estrogen receptor was immunoreactive specifically to a single band present in Nalm6/E47R but not the parental Nalm6 cells. Addition of tamoxifen increased the expression of cyclin D3 but not β-actin in Nalm6/E47R cells (data not shown), similar to that seen in K562/E47R and 697/E47 cells (66). Nalm6/E47R cells were lightly fixed, their chromatin was sheared, the E2A-bound DNA complex was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against the estrogen receptor, and the DNA was isolated. Quantitative PCR of the isolated DNA showed specific increased amplification localized to the two E boxes of the cyclin D3 promoter (Fig. 7B), strongly suggesting that cyclin D3 is a direct target of E2A.

FIG. 7.

ChIP analysis confirms that E2A binds the two E boxes in the cyclin D3 promoter. (A) The expressions of endogenous E2A and transduced E47R in Nalm6/E47R were analyzed by Western blot analysis, using antibodies against E47. The blot was stripped and reprobed, using antibodies against estrogen receptor (ER). (B) Chromatin from Nalm6 and Nalm6/E47R cells with and without tamoxifen were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to estrogen receptor and analyzed by quantitative PCR using primers that span the 2 E boxes (Ebox) in the promoter of cyclin D3. Flanking regions upstream (−0.3K) and downstream (+1K, +5K, and +10K) relative to the E boxes were also analyzed. The IgH intronic enhancer served as the internal positive control. The results represent the signal from anti-ER immunoprecipitated DNA divided by the signal from nonspecific IgG-immunoprecipitated DNA and were the averages of two independent analyses.

E2A can occupy its target sites without direct DNA binding.

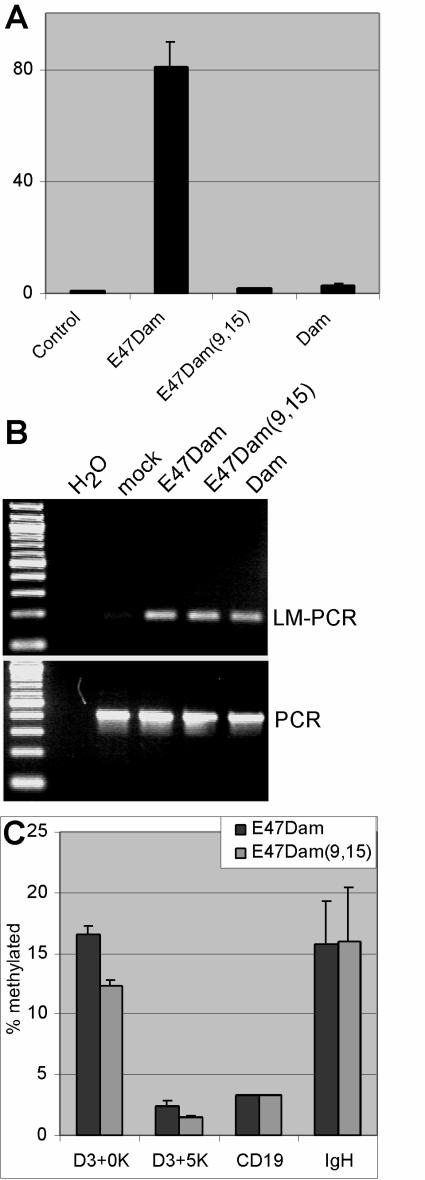

Although the E47Dam studies indicate that E2A binds the cyclin D3 gene, the promoter studies indicate that the induction of the cyclin D3 promoter does not depend on the E boxes. At least two models can potentially explain these somewhat contradictory results. One explanation is that E2A can regulate the cyclin D3 gene both indirectly via another factor and directly by binding other E boxes that are not present in the 1-kb promoter/enhancer region. The other is that E2A can bind the cyclin D3 promoter in an E-box-independent manner. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we engineered an E47Dam construct with mutations in the DNA binding domain and analyzed its activity in methylating the cyclin D3 promoter.

E47Dam was subjected to site-directed mutagenesis to convert the amino acids RR at positions 550 and 551 and R at position 563 in the DNA binding domain of E47 to GG and K, respectively. These two mutations are known to completely block DNA binding (58). The mutated E47Dam construct, designated E47Dam(9,15), had no E2A activity in a dual-luciferase assay using the (523)4 reporter (Fig. 8A), consistent with a lack of DNA binding by the mutated fusion protein. Transfection of E47Dam and E47Dam(9,15) constructs into 293T cells resulted in similar levels of protein expressions by Western blot analysis (data not shown). E47Dam(9,15) was expressed at high levels in 293T cells, and the genomic IgH intronic enhancer loci were analyzed by LM-PCR. The IgH enhancer locus was methylated (Fig. 8B), indicating that the C-terminal Dam portion of the mutated fusion protein retained its activity.

FIG. 8.

Mutations in the DNA binding domain (9,15) of E47Dam cause severe loss of transactivation activity but not methylation of the cyclin D3 gene. (A) 293T cells were transfected with (523)4 plasmid reporter and E47Dam, E47Dam(9,15), or Dam and then analyzed by dual-luciferase assay. (B) Genomic DNA was isolated from the transfected cells and then analyzed by LM-PCR or PCR for the IgH enhancer. (C) Nalm6 cells were transduced with lentiviruses that express E47Dam or E47Dam(9,15). Genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed by LM-PCR using real-time PCR. The percentages of methylation at different cyclin D3 loci were extrapolated from standard curves generated by using genomic DNA spiked with methylated inserts.

Next, lentiviruses encoding E47Dam(9,15) and E47FDam were used to transduce Nalm6 cells. Approximately 10 to 20% of the cells were transduced by flow cytometry for EGFP expression (data not shown). qLM-PCR analysis at the cyclin D3 loci demonstrated that E47Dam(9,15) methylated the cyclin D3 gene at D3+0K and D3+5K at levels similar to those seen with E47Dam (Fig. 8C), indicating that E47 without DNA binding activity can occupy the cyclin D3 promoter. The cyclin D3 promoter was methylated to the same level as the IgH intronic enhancer. Surprisingly, the IgH enhancer was equally methylated by E47FDam(9,15), suggesting that E2A can be recruited to multiple target genes independently of its E-box binding activity.

DISCUSSION

Normal E2A regulates cell cycle progression, an important contributor of cell accumulation that is frequently disrupted during carcinogenesis. Numerous studies support the current model that E2A inhibits cell cycle progression and functions as a tumor suppressor (19, 40, 41). Consistent with this model, E2A induces the expression of the CDKIs p21, INK4A, and INK4B (39, 42) that inhibit G1 cell cycle progression. However, other studies are inconsistent with the current model and demonstrate that E2A does not inhibit and can even promote cell cycle progression (12, 24, 39, 66). In support of these findings, we have previously identified cyclin D3, cyclin D2, and cyclin A as additional potential target genes of E2A (66) that can promote G1 cell cycle progression. The induction of both cyclins and CDKIs could explain the complicated and sometimes contradictory relationship between E2A and G1 progression.

This relationship would be better understood with further characterization of the mechanisms by which E2A induces CDKIs and cyclins. Toward this goal, we examined the mechanism by which E2A regulates the transcript levels of cyclin D3. Our initial working model predicted that E2A induced the expression of cyclin D3 via the two E boxes in the promoter. We found that E2A transactivated the 1-kb promoter region of cyclin D3, but the transactivation did not require the E boxes. Using the DamID approach, we demonstrated that E2A is bound at the chromatin-embedded cyclin D3 gene, but the binding did not require the DNA binding activity of E2A.

Cyclin D3 gene as a target gene of E2A and implications for oncogenesis.

The transactivation of cyclin D3 reporter and DNA binding at the cyclin D3 genomic locus by E2A strongly support our hypothesis that the cyclin D3 gene is a target gene of E2A. Although our studies were restricted to cultured cell lines, it is likely that the regulation of cyclin D3 by E2A applies to primary B cells. In normal lymph nodes, the highest expression levels for both E2A (48) and cyclin D3 (55) are seen within the rapidly proliferating germinal centers of a reactive lymph node.

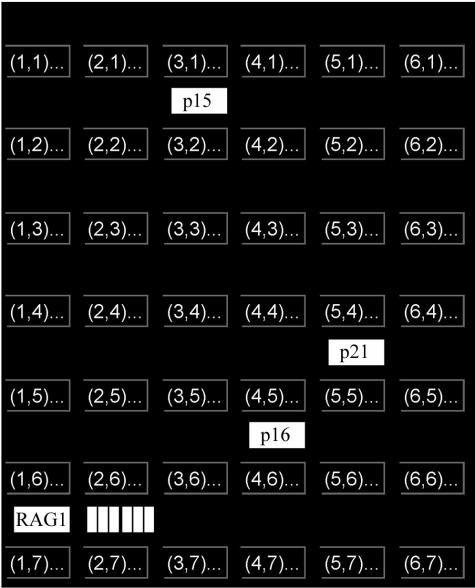

The expression of E2A is also correlated with cyclin D3 in primary precursor B cells. As an independent approach to identifying target genes of E2A, we analyzed the published transcript microarray results of primary precursor B leukemic cells (64) by using self-organizing map (SOM) analysis of GeneSpring analysis program (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, Calif.). In this clustering technique, genes with similar expression patterns are grouped together, and the groups are arranged in two dimensions (54). Groups with similar expression patterns are arranged closer together. If E2A activity correlates with E2A transcript levels, then the transcript levels of E2A and its target genes will correlate. Leukemic cells with low E2A will have low expression of target genes, while those with high E2A will have high expression of target genes. The 24,406 probes for the transcripts in primary precursor B lymphoblastic leukemia can be self-organized into a map of seven by six groups (Fig. 9). The three probes for E2A were clustered in a group (region 2,7) of 3,833 probes. A larger SOM with seven by seven groups placed the three probes for E2A into three different, although closely arranged and hence related, groups (data not shown). In the SOM of seven by six groups, the probes for the known target genes encoding IgH, TdT, lambda 5, cyclin D2, cyclin D3, and cyclin A clustered with those for E2A (region 2,7); the probe RAG-1 clustered in the adjacent region, 1,7 (348 probes), supporting the validity of using SOM to identify potential E2A target genes. The clustering of RAG-1 in a region adjacent to E2A may be related to the finding that E2A does not appear to occupy the RAG-1 promoter but does occupy a nearby RAG-2 enhancer (17, 20). The probes for p21, INK4A, and INK4B were clustered in regions distant from those of E2A, suggesting either that these genes are not true target genes of E2A or that the regulation of these genes by E2A is disrupted during leukemogenesis. We favor the latter because of the high incidence of deletion and promoter hypermethylation associated with these genes in pediatric ALLs (32, 45). EBF and VpreB could not be analyzed because they were not represented in the microarray chip. These findings suggest that in leukemic B cells, E2A expression is correlated with those of cyclins but not CDKIs, resulting in a net effect of E2A promoting cell proliferation. If true, then E2A may function as an oncogene rather than a tumor suppressor.

FIG. 9.

Known E2A target genes cluster together in a SOM cluster analysis of transcripts in primary human precursor B leukemic cells: SOM of seven by six groups with known E2A target genes. Region 2,7 contained probes for E2A and its target genes, those encoding IgH, lambda 5, TdT, cyclin D2, cyclin D3, and cyclin A. p16, INK4A; p15, INK4B.

In addition to promoting G1 cell cycle progression, cyclin D3 has additional properties not found in the related isoforms cyclin D2 and cyclin D1. Cyclin D3 is the major isoform of cyclin D expressed in most neoplastic precursor and mature human B cells (11, 14, 53, 55). Mature large-B-cell lymphomas overexpress cyclin D3 transcripts (52). In 10% of these lymphomas and recurrently in multiple myeloma, the overexpression is the result of the chromosomal translocation t(6;14), which juxtaposes the cyclin D3 gene and the IgH enhancer (4, 49, 52). Thus, overexpression of cyclin D3 transcripts is an important oncogenic event in B-cell neoplasms and further raises the possibility that E2A can function as an oncogene.

If E2A is already expressed in B cells and can induce cyclin D3, why do neoplastic B cells frequently contain t(6;14), which leads to cyclin D3 overexpression? This inconsistency could be explained by two potential nonexclusive explanations. First, E2A activation of cyclin D3 is dependent on necessary cofactors, and these factors are not present in plasma cells. For example, plasma cells do not express EBF (18), a transcription factor that cooperates with E2A to activate many B-cell-specific genes (16, 37, 46, 51). It is possible that in the absence of EBF, E2A cannot induce the expression of cyclin D3. Alternatively, E2A protein is not expressed or is not active in normal plasma cells but is aberrantly activated in plasma cell neoplasm and cell lines. Our preliminary studies suggest that E2A protein is low level to absent in normal plasma cells (data not shown), supporting the second explanation. This does raise some interesting and testable predictions. First, translation of E2A transcripts or protein stability of E2A protein is decreased in plasma cells compared to the level in lymphocytes. The decreased expression of E2A protein is disrupted in some plasma cell neoplasms. Finally, B-cell neoplasms with t(6;14) do not have to express high levels of E2A, while B cells neoplasms without t(6;14) would be expected to have high expression levels of E2A to induce cyclin D3 transcripts.

Our hypothesis of decreased expression of the E2A protein in plasma cells does appear to contradict the findings that E2A transcript message is expressed uniformly throughout normal human mature B cells to plasma cell differentiation (31) and E2A protein is expressed ubiquitously in different B-cell lines from early immature precursor cells to late plasma cell lines (21). The contradictory differences in E2A protein expression in plasma cells may reflect the difference between postmitotic normal plasma cells and proliferating plasma cell lines. The contradictory differences in E2A transcript expression in normal plasma cells may reflect change in transcript levels during isolation of plasma cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting or decreased translation of E2A transcripts in plasma cells. In situ hybridization for E2A transcripts and flow cytometry for E2A protein should provide further insight into the role of E2A in late B cells and plasma cells.

DamId as an approach to identifying target genes.

DamID has been used to identify target genes in yeast and Drosophila. We provide the first evidence that DamID can be applied to mammalian/human cells. This approach has advantages over the other two main techniques, ChIP and PinPoint, for identifying chromatin-embedded DNA targets. ChIP requires many cells and highly specific antibodies. Antibodies may no longer be a significant issue for E2A, since ChIP assays for E2A have been recently reported using monoclonal antibodies against E2A or directed against an epitope-tagged E2A (17, 20, 56). The Pinpoint technique, which utilizes fusion constructs between a DNA endonuclease and a transcription factor (27), introduces DNA nicks that are likely to generate a DNA damage-and-repair response. In contrast, Dam in transgenic Drosophila had little effect on development (62). The utilization of LM-PCR permits analysis of a heterogeneous population of cells in which only a subpopulation expresses the fusion construct and is amenable for analysis of primary human cells, which are often available in small numbers. Our studies indicate that LM-PCR can be performed with less than 2 μg of genomic DNA with only 3% of the cells expressing the Dam fusion protein. E47Dam selectively methylated at the promoter region of cyclin D3 despite the large number of consensus E boxes throughout the cyclin D3 gene (Fig. 5A), indicating that only a subset of E boxes are actually occupied by E2A. Similar selective occupancy of a subset of potential consensus sites has been noted for the zinc finger GATA-1 transcription factor (22).

One limitation of our analysis is the difficulty in determining the percentage of transduced cells that express the DamID constructs, despite their coexpression of EGFP as an internal ribosomal entry site transcript. This is because DamID constructs and hence EGFP expression must be expressed at low levels to suppress nonspecific methylation. The transfection efficiency could be potentially quantified by quantitative PCR for viral integration. But this approach is subject to the number of viral integration in each cell, and thus, the number of integrations may not correlate with the number of transduced cells. Without an accurate percentage of transduced cells, we cannot be certain if the altered methylation resulting from mutations in the constructs reflects differences in DNA occupancies or differences in transduction efficiencies. We favor the latter, since the estimated EGFP expression correlates well with the level of methylation.

A more conclusive study would require dual promoter retrovirus vectors that express EGFP off a strong promoter and the DamID construct off a weak promoter. Alternatively, the Dam portion could be mutated to decrease its inherent binding activity but retain its methylation activity. DamID using this mutated Dam may provide more specific and localized methylation even at high levels of expression.

E2A occupies the cyclin D3 and IgH loci despite loss of DNA binding.

Our studies demonstrate that the E2A-Dam fusion protein can occupy the cyclin D3 promoter and IgH intronic enhancer despite mutations that block DNA binding and decrease the transactivation of an E2A reporter to the basal level. Although we cannot completely exclude some weak binding of the mutated E2A-Dam protein to E2A target sites, we think it unlikely, since the methylation was not significantly altered compared to a more than 97% decrease in the transactivation activity. These findings also argue against DNA binding of E2A to a cryptic non-E-box site and suggest that E2A can be recruited to its target genes independently of its DNA binding. A likely possibility is that E2A forms a complex containing other DNA binding factors that recognizes the cyclin D3 promoter and IgH enhancer. This would be reminiscent of the interaction of MEF2 and MyoD, which permits cooperative activation of gene expression via DNA binding by only one of the factors (33). An important implication of this possibility is that the oncogenic E2A fusion proteins or E2A-Id heterodimers without E-box binding activity may still occupy a subset of E2A target genes if they can form a complex with other DNA binding factors.

The effect of the nonbinding E2A on the transcription of its target genes is an important issue that we have not addressed. Nonbinding E2A can or cannot induce the transcription of its target genes. We predict that both possibilities are likely and gene dependent, because studies of the transcription factor c-myc demonstrated that DNA occupancy does not necessarily lead to transcription regulation (13, 36). The exact relationship between E2A, mutated E2A, and transcription will require a more-extensive survey of the E2A target genes, a survey that is readily amenable to the combined techniques of DamID and genomic microarray analysis.

Finally, the identities of the potential E2A-interacting DNA binding factors at the cyclin D3 promoter are not known. Potential candidates are SP1 (60), AP2 (63), and E2F1 (30), which have been identified as transactivating and binding the cyclin D3 promoter. None of these factors has been shown to cooperate with E2A. EBF is also a potential candidate because it has been shown to cooperate with E2A (16, 37, 51) to induce multiple target genes. Preliminary studies suggest that EBF can transactivate the cyclin D3 reporter. Future studies to identify the critical domains of E2A that recruit it to the cyclin D3 promoter, the interacting DNA binding factors, and the effect on cyclin D3 expression will increase our understanding of the relationship among E2A, its oncogenic forms, and cell cycle regulation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando, K., F. Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista, and J. D. Griffin. 1993. Regulation of G1/S transition by cyclins D2 and D3 in hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9571-9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain, G., E. C. Maandag, D. J. Izon, D. Amsen, A. M. Kruisbeek, B. C. Weintraub, I. Krop, M. S. Schlissel, A. J. Feeney, and M. van Roon. 1994. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell 79:885-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartkova, J., J. Lukas, M. Strauss, and J. Bartek. 1998. Cyclin D3: requirement for G1/S transition and high abundance in quiescent tissues suggest a dual role in proliferation and differentiation. Oncogene 17:1027-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergsagel, P. L., and W. M. Kuehl. 2001. Chromosome translocations in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 20:5611-5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boonen, G. J., B. A. van Oirschot, A. van Diepen, W. J. Mackus, L. F. Verdonck, G. Rijksen, and R. H. Medema. 1999. Cyclin D3 regulates proliferation and apoptosis of leukemic T cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34676-34682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks, A. R., D. Shiffman, C. S. Chan, E. E. Brooks, and P. G. Milner. 1996. Functional analysis of the human cyclin D2 and cyclin D3 promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9090-9099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter, R. S., P. Ordentlich, and T. Kadesch. 1997. Selective utilization of basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper proteins at the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:18-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, M. W., E. Barr, M. M. Lu, K. Barton, and J. M. Leiden. 1995. Adenovirus-mediated over-expression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty. J. Clin. Investig. 96:2260-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, J. K., N. Hoang, A. M. Vilardi, P. Conrad, S. G. Emerson, and A. M. Gewirtz. 2001. Hybrid HIV/MSCV LTR enhances transgene expression of lentiviral vectors in human CD34(+) hematopoietic cells. Stem Cells 19:236-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi, J. K., C. P. Shen, H. S. Radomska, L. A. Eckhardt, and T. Kadesch. 1996. E47 activates the Ig-heavy chain and TdT loci in non-B cells. EMBO J. 15:5014-5021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker, T., F. Schneller, S. Hipp, C. Miething, T. Jahn, J. Duyster, and C. Peschel. 2002. Cell cycle progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is controlled by cyclin D2, cyclin D3, cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) 4 and the cdk inhibitor p27. Leukemia 16:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel, I., and C. Murre. 1999. Ectopic expression of E47 or E12 promotes the death of E2A-deficient lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:996-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez, P. C., S. R. Frank, L. Wang, M. Schroeder, S. Liu, J. Greene, A. Cocito, and B. Amati. 2003. Genomic targets of the human c-Myc protein. Genes Dev. 17:1115-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filipits, M., U. Jaeger, G. Pohl, T. Stranzl, I. Simonitsch, A. Kaider, C. Skrabs, and R. Pirker. 2002. Cyclin D3 is a predictive and prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 8:729-733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsberg, E. C., K. M. Downs, H. M. Christensen, H. Im, P. A. Nuzzi, and E. H. Bresnick. 2000. Developmentally dynamic histone acetylation pattern of a tissue-specific chromatin domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14494-14499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gisler, R., and M. Sigvardsson. 2002. The human V-preB promoter is a target for coordinated activation by early B cell factor and E47. J. Immunol. 168:5130-5138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenbaum, S., and Y. Zhuang. 2002. Identification of E2A target genes in B lymphocyte development by using a gene tagging-based chromatin immunoprecipitation system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15030-15035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagman, J., A. Travis, and R. Grosschedl. 1991. A novel lineage-specific nuclear factor regulates mb-1 gene transcription at the early stages of B cell differentiation. EMBO J. 10:3409-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herblot, S., P. D. Aplan, and T. Hoang. 2002. Gradient of E2A activity in B-cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:886-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu, L. Y., J. Lauring, H. E. Liang, S. Greenbaum, D. Cado, Y. Zhuang, and M. S. Schlissel. 2003. A conserved transcriptional enhancer regulates RAG gene expression in developing B cells. Immunity 19:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs, Y., C. Vierra, and C. Nelson. 1993. E2A expression, nuclear localization, and in vivo formation of DNA- and non-DNA-binding species during B-cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7321-7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, K. D., J. A. Grass, M. E. Boyer, C. M. Kiekhaefer, G. A. Blobel, M. J. Weiss, and E. H. Bresnick. 2002. Cooperative activities of hematopoietic regulators recruit RNA polymerase II to a tissue-specific chromatin domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11760-11765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato, J. Y., and C. J. Sherr. 1993. Inhibition of granulocyte differentiation by G1 cyclins D2 and D3 but not D1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11513-11517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kee, B. L., R. R. Rivera, and C. Murre. 2001. Id3 inhibits B lymphocyte progenitor growth and survival in response to TGF-beta. Nat. Immunol. 2:242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kladde, M. P., and R. T. Simpson. 1994. Positioned nucleosomes inhibit Dam methylation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1361-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudsen, K. E., A. F. Fribourg, M. W. Strobeck, J. M. Blanchard, and E. S. Knudsen. 1999. Cyclin A is a functional target of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein-mediated cell cycle arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27632-27641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, J. S., C. H. Lee, and J. H. Chung. 1998. Studying the recruitment of Sp1 to the beta-globin promoter with an in vivo method: protein position identification with nuclease tail (PIN*POINT). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:969-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lisitsyn, N., and M. Wigler. 1993. Cloning the differences between two complex genomes. Science 259:946-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Look, A. T. 1997. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science 278:1059-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, Y., J. Yuan, M. Huang, R. Jove, and W. D. Cress. 2003. Regulation of the cyclin D3 promoter by E2F1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16770-16776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmoud, M. S., N. Huang, M. Nobuyoshi, I. A. Lisukov, H. Tanaka, and M. M. Kawano. 1996. Altered expression of Pax-5 gene in human myeloma cells. Blood 87:4311-4315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloney, K. W., L. McGavran, L. F. Odom, and S. P. Hunger. 1998. Different patterns of homozygous p16INK4A and p15INK4B deletions in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias containing distinct E2A translocations. Leukemia 12:1417-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molkentin, J. D., B. L. Black, J. F. Martin, and E. N. Olson. 1995. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell 83:1125-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okamoto, A., D. J. Demetrick, E. A. Spillare, K. Hagiwara, S. P. Hussain, W. P. Bennett, K. Forrester, B. Gerwin, M. Serrano, D. H. Beach, et al. 1994. Mutations and altered expression of p16INK4 in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11045-11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orian, A., B. Van Steensel, J. Delrow, H. J. Bussemaker, L. Li, T. Sawado, E. Williams, L. W. Loo, S. M. Cowley, C. Yost, S. Pierce, B. A. Edgar, S. M. Parkhurst, and R. N. Eisenman. 2003. Genomic binding by the Drosophila Myc, Max, Mad/Mnt transcription factor network. Genes Dev. 17:1101-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Riordan, M., and R. Grosschedl. 1999. Coordinate regulation of B cell differentiation by the transcription factors EBF and E2A. Immunity 11:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pagano, M., R. Pepperkok, F. Verde, W. Ansorge, and G. Draetta. 1992. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 11:961-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagliuca, A., P. Gallo, P. De Luca, and L. Lania. 2000. Class A helix-loop-helix proteins are positive regulators of several cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors' promoter activity and negatively affect cell growth. Cancer Res. 60:1376-1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park, S. T., G. P. Nolan, and X. H. Sun. 1999. Growth inhibition and apoptosis due to restoration of E2A activity in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J. Exp. Med. 189:501-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peverali, F. A., T. Ramqvist, R. Saffrich, R. Pepperkok, M. V. Barone, and L. Philipson. 1994. Regulation of G1 progression by E2A and Id helix-loop-helix proteins. EMBO J. 13:4291-4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prabhu, S., A. Ignatova, S. T. Park, and X. H. Sun. 1997. Regulation of the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 by E2A and Id proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5888-5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quelle, D. E., R. A. Ashmun, S. A. Shurtleff, J. Y. Kato, D. Bar-Sagi, M. F. Roussel, and C. J. Sherr. 1993. Overexpression of mouse D-type cyclins accelerates G1 phase in rodent fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 7:1559-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynisdottir, I., K. Polyak, A. Iavarone, and J. Massague. 1995. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-beta. Genes Dev. 9:1831-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roman-Gomez, J., J. A. Castillejo, A. Jimenez, M. G. Gonzalez, F. Moreno, C. Rodriguez Mdel, M. Barrios, J. Maldonado, and A. Torres. 2002. 5′ CpG island hypermethylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the p21(CIP1/WAF1/SDI1) gene and confers poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 99:2291-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romanow, W. J., A. W. Langerak, P. Goebel, I. L. Wolvers-Tettero, J. J. van Dongen, A. J. Feeney, and C. Murre. 2000. E2A and EBF act in synergy with the V(D)J recombinase to generate a diverse immunoglobulin repertoire in nonlymphoid cells. Mol. Cell 5:343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruezinsky, D., H. Beckmann, and T. Kadesch. 1991. Modulation of the IgH enhancer's cell type specificity through a genetic switch. Genes Dev. 5:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rutherford, M. N., and D. P. LeBrun. 1998. Restricted expression of E2A protein in primary human tissues correlates with proliferation and differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 153:165-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaughnessy, J., Jr., A. Gabrea, Y. Qi, L. Brents, F. Zhan, E. Tian, J. Sawyer, B. Barlogie, P. L. Bergsagel, and M. Kuehl. 2001. Cyclin D3 at 6p21 is dysregulated by recurrent chromosomal translocations to immunoglobulin loci in multiple myeloma. Blood 98:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen, C. P., and T. Kadesch. 1995. B-cell-specific DNA binding by an E47 homodimer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4518-4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigvardsson, M., M. O'Riordan, and R. Grosschedl. 1997. EBF and E47 collaborate to induce expression of the endogenous immunoglobulin surrogate light chain genes. Immunity 7:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonoki, T., L. Harder, D. E. Horsman, L. Karran, I. Taniguchi, T. G. Willis, S. Gesk, D. Steinemann, E. Zucca, B. Schlegelberger, F. Sole, A. J. Mungall, R. D. Gascoyne, R. Siebert, and M. J. Dyer. 2001. Cyclin D3 is a target gene of t(6;14)(p21.1;q32.3) of mature B-cell malignancies. Blood 98:2837-2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki, R., H. Kuroda, H. Komatsu, Y. Hosokawa, Y. Kagami, M. Ogura, S. Nakamura, Y. Kodera, Y. Morishima, R. Ueda, and M. Seto. 1999. Selective usage of D-type cyclins in lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia 13:1335-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tamayo, P., D. Slonim, J. Mesirov, Q. Zhu, S. Kitareewan, E. Dmitrovsky, E. S. Lander, and T. R. Golub. 1999. Interpreting patterns of gene expression with self-organizing maps: methods and application to hematopoietic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2907-2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teramoto, N., K. Pokrovskaja, L. Szekely, A. Polack, T. Yoshino, T. Akagi, and G. Klein. 1999. Expression of cyclin D2 and D3 in lymphoid lesions. Int. J. Cancer 81:543-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tremblay, M., S. Herblot, E. Lecuyer, and T. Hoang. 2003. Regulation of pTα gene expression by a dosage of E2A, HEB, and SCL. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12680-12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Steensel, B., and S. Henikoff. 2000. Identification of in vivo DNA targets of chromatin proteins using tethered dam methyltransferase. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:424-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voronova, A., and D. Baltimore. 1990. Mutations that disrupt DNA binding and dimer formation in the E47 helix-loop-helix protein map to distinct domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4722-4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waldman, T., K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1995. p21 is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 55:5187-5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, Z., Y. Zhang, J. Lu, S. Sun, and K. Ravid. 1999. Mpl ligand enhances the transcription of the cyclin D3 gene: a potential role for Sp1 transcription factor. Blood 93:4208-4221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weintraub, H., T. Genetta, and T. Kadesch. 1994. Tissue-specific gene activation by MyoD: determination of specificity by cis-acting repression elements. Genes Dev. 8:2203-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wines, D. R., P. B. Talbert, D. V. Clark, and S. Henikoff. 1996. Introduction of a DNA methyltransferase into Drosophila to probe chromatin structure in vivo. Chromosoma 104:332-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang, M., H. Nomura, Y. Hu, S. Kaneko, H. Kaneko, M. Tanaka, and K. Nakashima. 1998. Prolactin-induced expression of TATA-less cyclin D3 gene is mediated by Sp1 and AP2. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 44:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeoh, E. J., M. E. Ross, S. A. Shurtleff, W. K. Williams, D. Patel, R. Mahfouz, F. G. Behm, S. C. Raimondi, M. V. Relling, A. Patel, C. Cheng, D. Campana, D. Wilkins, X. Zhou, J. Li, H. Liu, C. H. Pui, W. E. Evans, C. Naeve, L. Wong, and J. R. Downing. 2002. Classification, subtype discovery, and prediction of outcome in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Cancer Cell 1:133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Young, J. L., and R. W. Miller. 1975. Incidence of malignant tumors in U.S. children. J. Pediatr. 86:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao, F., A. Vilardi, R. J. Neely, and J. K. Choi. 2001. Promotion of cell cycle progression by basic helix-loop-helix E2A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6346-6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhuang, Y., P. Cheng, and H. Weintraub. 1996. B-lymphocyte development is regulated by the combined dosage of three basic helix-loop-helix genes, E2A, E2-2, and HEB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2898-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhuang, Y., P. Soriano, and H. Weintraub. 1994. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell 79:875-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]