Abstract

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a lung disorder which was first described in 1958 by Rosen et al. and is indeed rare disease with a prevalence of 0.1 per 100,000 individuals. PAP is characterized by abnormal accumulation of pulmonary surfactant in the alveolar space, which impairs gas exchange leading to a severe hypoxemia. Pulmonary surfactant is an insoluble proteinaceous material that is rich in lipids and stains positive with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS). The most common type of PAP is the so‐called autoimmune or idiopathic type. It has been hypothesized that deficiency in granulocyte macrophage–colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), as a result of the anti‐GM‐CSF antibody production, is strongly related to impaired surfactant recycling that leads to the accumulation of surfactant in the alveolar space. Its clinical course is variable from spontaneous remission in the best case scenario, going through the entire spectrum of disease severity, towards fatal respiratory failure. Whole lung lavage has been the gold standard therapy in PAP until the advent of GM‐CSF. Although the first case was reported to be idiopathic, subsequent analysis revealed that Pneumocystis jirovecii, silica, and other inhalational toxins were able to trigger this reaction. In this study, we report the case of a 52‐year‐old man who developed PAP syndrome after a 2‐year exposure to silica dust. Our review of the world literature that includes 363 cases reported until now, reflects the evolution of science and technology in determining different aetiologies and diagnostic tests that lead to an improved perspective in the life of these patients.

Keywords: granulocyte macrophage—colony stimulating factor, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

Introduction

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) was first described in 1958 by Rosen et al. as an infrequently seen disorder in which an amorphous, insoluble, lipoproteinaceous material tends to accumulate in the alveolar spaces, causing impairment of gas exchange 1. Although the first reported cases were felt to be idiopathic, there have been subsequent reports suggesting that PAP could be a secondary phenomenon, resulting from exposure to silica, silicates, aluminium, fibreglass particles, and infectious agents such as Pneumocystis jirovecii, Nocardia, and mycobacteria, as well as associated with haematological malignancies. We report the case of a man who developed PAP syndrome following a 2‐year exposure to silica dust and subsequently reviewed the world literature where 363 cases were found.

Case Report

A 52‐year‐old white male with a 60 pack‐year history of cigarette smoking presented with progressive dyspnoea on exertion for 18 months. He had worked in an environment where other workers were placing tiles and cutting floors, without wearing a mask. He had a long‐standing cough with whitish sputum production, but denied fever, chills, weight loss, night sweats, and other symptoms.

Physical examination revealed a mildly dyspnoeic patient with normal vital signs; heart auscultation was normal; bibasilar fine late inspiratory rales involving half the way up in both lung fields were heard. Laboratory analyses showed haemoglobin (Hb) 17 g/dL, white blood cells (WBC) 8.700/mm3, and routine chemistry results including liver function tests were normal. Arterial blood gases: PaO2, 76 mmHg; PaCO2, 35 mmHg; and pH, 7.44. Pulmonary function tests revealed FVC: 4.69 L (89% of predicted), FEV1 3.73 L (92%), FEV1/FVC 80%, TLC 5.76 L (78%), and DLCO 16.8 mL/min/mmHg (54%). Chest radiograph revealed bilateral alveolar infiltrates (Fig. 1). Fiberoptic bronchoscopy failed to reveal any endobronchial lesion but yielded biopsies disclosing alveoli filled with periodic acid of Schiff (PAS)‐positive lipoproteinaceous material and refringent particles compatible with silicates, and negative cultures (Fig. 2A, B). A therapeutic whole lung lavage (WLL) was carried out, resulting is an immediate improvement in symptoms as well as in gas exchange.

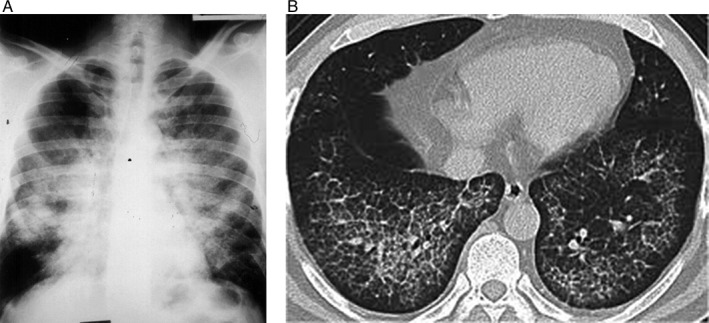

Figure 1.

(A) Chest X‐ray and (B) computerized tomography of the chest disclosing bilateral alveolar infiltrates in butterfly distribution, sparing the costophrenic angles characteristic of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.

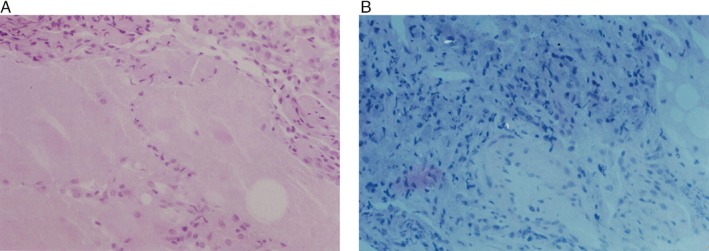

Figure 2.

(A) High power view of an H&E stain of lung biopsy revealing alveoli filled with periodic acid–Schiff‐positive proteinaceous material. (B) Polarized light microscopy showing birefringent particles compatible with silicate deposits in the pulmonary interstitium.

Discussion

This case supports the hypothesis that PAP should not be considered idiopathic until we exclude all the occupational aetiologies. Indeed, the relationship between the occupational exposure and the pulmonary reaction is evident in this patient. The intra‐alveolar accumulation of PAS‐positive material designated as PAP, has been reported to occur occasionally in workers exposed to high concentrations of fine particulate silica. This condition was first reported in 1969 by Buechner et al. 2.

When humans and animals inhale high concentrations of silica over a short period of time, the lining cells of the airways are damaged and a lipid‐rich protein exudate accumulates, obliterating the air spaces. These events are followed by type II pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and increased production of phospholipid. In an experimental model, production of dipalmitoyl lecithin increased threefold, while the elimination of the material decreased. Under these circumstances, phagocytosis and the removal of particles were impaired 3, 4. Rats exposed to high concentration of quartz dust developed alveolar proteinosis with some foci of desquamative pneumonitis and there was a great deal of aggregated silica in that proteinaceous material 5. Since 1980 there have been several cases published in the English literature of PAP with silicosis and we think that some cases could have been assumed to be idiopathic PAP 6. This case report of silica dust exposure coexisting with PAP, and the experimental finding that inhaled fine silica dust in animals can cause a similar disease 7, support the hypothesis that inhaled dust is responsible for the development of PAP, which may not be just a rare idiopathic disease entity, but perhaps a mere, somewhat uncommon pulmonary reaction to a noxious agent. Abraham and McEven, using scanning electron microscopy, demonstrated the presence of inorganic particulates in histological specimens from patients previously diagnosed with PAP 8, and they also found that the count of birefringent particles was significantly higher in patients with PAP than in control history and accumulation of inorganic particles in the gas spaces of the lungs. Therefore, it is possible that PAP has multiple causes and that inhaled dusts is one of them.

A literature review was done using Medline. Three hundred and sixty‐three cases were obtained in 36 manuscripts. The chart was arranged chronologically and contained the number of cases per study, the average age in each study, the type of PAP, the way the diagnosis was made, the treatment given, and the survival.

Table 1 shows the compilation of 363 chronologically arranged cases worldwide from 1988 to 2014. The age at the diagnosis varied from 1 to 79 years. PAP was classified into three groups regarding the aetiology: autoimmune or idiopathic (293 cases of 352 classifiable cases, which represents 83% of the cases), secondary (56 of the 352, which stands for 16% of the classifiable cases), and congenital (only 3 cases reported as such, which comprise 1% of the total). Twelve cases of 363 were not classifiable. PAP was diagnosed on the basis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), or open lung biopsy (OLB). Until year 2006, WLL was the only treatment for PAP and the survival was almost 100%. In 2006, oncology researchers discovered serendipitously that knockout mice deprived of granulocyte macrophage–colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) gene or receptor developed full blown PAP, which was ameliorated by the administration of GM‐CSF. Thereafter it was conceptualized that GM‐CSF plays an important role in the homeostasis of surfactant production in the alveolar milieu, and then the usefulness of administering GM‐CSF to improve this condition was readily acknowledged. Subsequently, a dual therapy consistent in administration of GM‐CSF and WLL was established.

Table 1.

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis world literature review.

| Reference no. | Year | N | Ave. age | Autoimmune or idiopathic | Secondary | Congenital | Contrib. factors | Diagnostic method | Treatment | Survival % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bracci 9 | 1988 | 1 | 49 | 1 | OLB | BAL | 100 | |||

| Lopez 10 | 1991 | 2 | 37 | 2 | OLB | SR | 100 | |||

| Chaudhuri 11 | 1996 | 1 | 26 | 1 | TB | BAL/OLB | Anti‐TB treatment | 100 | ||

| Kim 12 | 1999 | 12 | TBLB |

9 WLL 3 Untreated |

75 | |||||

| Kokturk 13 | 2000 | 1 | 37 | 1 | TBB/BAL | WLL | 100 | |||

| Wali 14 | 2000 | 1 | 29 | 1 | TBB | WLL | 100 | |||

| Barraclough 15 | 2001 | 1 | 34 | 1 | TBB | GM‐CSF | 100 | |||

| Beccaria 16 | 2004 | 21 | 21 |

4 TBB 10 OLB |

WLL | 100 | ||||

| Kattan 17 | 2004 | 1 | 1 | WLL | ||||||

| ker 18 | 2004 | 1 | 51 | 1 | TBB | WLL | 100 | |||

| Kotov 19 | 2006 | 1 | 25 | 1 | PJP | BAL | BAL | 100 | ||

| Indira 20 | 2006 | 1 | 53 | DM | OLB | WLL | 100 | |||

| Thomson 21 | 2006 | 4 | 27 | 4 | OLB |

1 SR 3 WLL |

100 | |||

| Tazawa 22 | 2006 | 35 | 35 | Autoimmune | 25 GM‐CSF | 100 | ||||

| Froudarakis 23 | 2006 | 1 | 13 | 1 | BAL | WLL | 100 | |||

| Wylam 24 | 2006 | 12 | 43 | 12 | 11 GM‐CSF | 93 | ||||

| Ceruti 25 | 2007 | 1 | 10 | 1 | LPI | BAL | WLL | 100 | ||

| Borie 26 | 2009 | 1 | 41 | 1 | TBB | Rituximab | 100 | |||

| Ryushi 27 | 2010 | 50 | 50 | 35 GM‐CSF | ||||||

| Hodges 28 | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Hepatosplenomegaly | BAL | 100 | |||

| Byun 29 | 2010 | 38 | 38 | TBB/BAL | WLL | 97 | ||||

| Ahmed 30 | 2010 | 8 | 2 | 8 | OLB | WLL/GM‐CSF | 25 | |||

| Tekgul [ 31 ] | 2011 | 1 | 46 | 1 | TB | TBB | Anti‐TB treatment | 100 | ||

| Moreland 32 | 2011 | 1 | 59 | 1 | Exposure to cotton | TBB | WLL | 100 | ||

| Yaqub 33 | 2011 | 39 | 39 | BAL | WLL/Mycophenolate | 100 | ||||

| Bonella 34 | 2011 | 70 | 64 | 6 | CML | BAL‐TBB | WLL | |||

| Tejwani 35 | 2011 | 1 | 1 | HIV | TBB | WLL | 100 | |||

| Canellas 36 | 2012 | 1 | 21 | 1 | TBB | SR | 100 | |||

| Khan 37 | 2012 | 5 | 37 | 4 | 1 |

4 OLB 1 TBB |

2 WLL/GM‐CSF 1 TMP/SMX 1 GM‐CSF |

100 | ||

| Shende 38 | 2013 | 1 | 58 | 1 | HTN, old TB | WLL/GM‐CSF | 100 | |||

| Hammami 39 | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | BAL | WLL | 0 | |||

| Main 40 | 2013 | 1 | 79 | 1 | CLL, PNA | TBB | WLL | 100 | ||

| Bansal 41 | 2013 | 1 | 54 | TBB | WLL/GM‐CSF | 100 | ||||

| Rojanapremsuk 42 | 2013 | 1 | 47 | 1 | PNA, sinusitis | TBB/BAL | Refused treatment | |||

| Ishii 43 | 2014 | 31 | 50 | 31 | MDS | TBB/OLB | ||||

| Fijotek 44 | 2014 | 17 | 13 | 4 | BAL/TBB | WLL in 75% | 94 | |||

| Totals | 363 | 293 | 56 | 3 |

BAL, broncho‐alveolar lavage; CML, chronic myloid leukaemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; GM‐CSF, granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor; HTN, hypertension; OLB, open lung biopsy; partial LL, partial lung lavage; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; PJP, pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia; PNA, pneumonia; SR, spontaneous remission; TB, tuberculosis; TBB, transbronchial biopsy; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfametoxazole; WLL, whole lung lavage.

WLL had been the standard of therapy since the report by Ramirez 45 and consequently we managed this reported patient using that intervention. The patient was placed under general anaesthesia, and a double lumen endotracheal tube was inserted; the dependent lung was placed down, a bronchoscope was inserted and after wedging it in a distant airway, we started lavage by instilling normal saline and then suctioning intermittently. Initially we obtained a lavageate that was markedly creamy due to the high lipoproteinaceous content and subsequently it became clear. Approximately 20 L had to be suctioned to get to this point. A week later, we performed WLL of the second lung.

The double lumen endotracheal tube is a key factor because we can **obturate and ventilate one lung and work in the other one. Most of the experts use the “eyeball technique” to estimate how much of lavage is sufficient. The frequency of lavage has to be individualized.

After the advent of GM‐CSF it became a major contributing factor because it was recognized that its deficiency or absence would lead to a significant accumulation of surfactant in the alveolar space. The management of PAP changed forever after this because it became customary to first try GM‐CSF and use WLL only for the therapeutic failure of GM‐CSF. GM‐CSF has been used via inhalational, systemic, or subcutaneous delivery with comparable results.

Finally, it is of utmost importance to analyse and improve the environment of patients. Avoidance of exposure to triggering agents such as silica, mould, or any infective or toxic material is the cornerstone of management of secondary type PAP.

Disclosure Statements

No conflict of interest declared.

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Huaringa, A.J. and Francis, W.H. (2016) Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a case report and world literature review. Respirology Case Reports, 4 (6), e00201. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.201.

Associate Editor: Fraser Brims

References

- 1. Rosen S, Castleman B, and Liebow A 1958. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 258:1123–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buechner H, and Ansary A 1969. Acute Silico‐proteinosis. Dis. Chest. 55:274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silicosis and Silicate Disease Committee 1988. Disease associated with exposure to silica and non‐fibrous silicate minerals. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 112:673–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heppleston A 1979. Silica and asbestos: contrast in tissue response. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 330:725–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gross P, and de Trebille R 1968. Alveolar proteinosis: its experimental production in rodents. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 86:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubin E, Weisbrod G, Sanders D. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Radiology 1980; 135:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heppleston A, Wright N, and Stewart J 1970. Experimental alveolar lipo‐proteinosis following the inhalation of silica. J. Pathol. 101:293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abraham JL, and McEuen D 1986. Inorganic particulates associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Appl. Pathol. 4(3):138–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bracci L 1988. Role of physical therapy in management of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a case report. Phys. Ther. 68:686–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martfnez‐Lopez MA, Cerezo G, Villasante C, et al. 1991. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: prolonged spontaneous remission in two patients. Eur. Respir. J. 4:377–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaudhuri R, Prabhudesai P, Vaideeswan P, et al. 1996. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis with pulmonary tuberculosis. Ind. J. Tub. 43:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim G, Lee S, Lee H, et al. 1999. The clinical characteristics of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: experience at Seoul National University Hospital, and review of the literature. J. Korean Med. Sci. 14:159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kokturk N, Oğuzülgen İ, Haluk T, et al. 2000. A case report: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Turk. Respir. J. 1:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wali SO, Samman YS, Altaf F, et al. 2000. Primary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a case report and a review of the literature. Ann. Saudi Med. 20:3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barraclough RM, and Gillies AJ 2001. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a complete response to GM‐CSF therapy. Thorax 56:664–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beccaria M., Luisetti M., Rodi G., et al. . Long‐term durable benefit after whole lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2004; 23:526–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abdulhakiem K, Prakash SB, and Ifthikar HM 2004. Congenital alveolar proteinosis. Saudi Med. J. 25(10):1474–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ker JM 2004. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis—a case report and review. SA J. Radiol. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kotov PV, and Shidham VB 2006. Alveolar proteinosis in a patient recovering from Pneumocystis cariniiinfection: a case report with a review of literature. CytoJournal 3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumari I, Rajesh V, Darsana V, et al. 2007. Whole lung lavage: the salvage therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Indian J. Chest Dis. Allied Sci. 49:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomson JC, Kishima M, Gomes MU, et al. 2006. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: four cases. J. Bras. Pneumol 32(3):261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tazawa R, Nakata K, Inoue Y, et al. 2006. Granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor inhalation therapy for patients with idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a pilot study; and long‐term treatment with aerosolized granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor: a case report. Respirology 41:S61–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marios E, Koutsopoulosb A, Helen P, et al. 2007. Total lung lavage by awake flexible fiberopticbronchoscope in a 13‐year‐old girl with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Respir. Med. 101:366–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wylam ME, Ten R, Prakash UBS, et al. 2006. Aerosol granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur. Respir. J. 27:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ceruti M, Rodi G, Giulia MS, et al. 2007. Successful whole lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis secondary to lysinuric protein intolerance: a case report. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Borie R, Debray MP, Laine C, et al. 2009. Rituximab therapy in autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur. Respir. J. 33:1503–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rushi T, Inoue Y, Arai T, et al. 2010. Aerosol GM‐CSF therapy of PAP. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181:1345–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hodges O, Zar HJ, Mamathuba R, et al. 2010. Bilateral partial lung lavage in an infant with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Br. J. Anaesth. 104(2):228–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Byun MK, Kim DS, Kim YW, et al. 2010. Clinical features and outcomes of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Korean population. J. Korean Med. Sci. 25:393–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tabatabaei S, Karimi A, Tabatabaei R, et al. 2010. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in children: a case series. J. Res. Med. Sci. 15:120–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tekgül S, Bilaceroglu S, Ozkaya S, et al. 2012. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and superinfection with pulmonary tuberculosis in a case. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 5:25e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moreland A, Kijsirichareanchai K, Alalawi R, et al. 2011. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in a man with prolonged cotton dust exposure. Respir. Med. CME 4:121–123. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yaqub Sabeen, Harkins Michelle S.. A 39 year old female with progressive dyspnea, dry cough and hypoxia: a case report. Southwest J. Pulm. Crit. Care. 2011; 3:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bonella F, Ohshimo S, Miaotian C, et al. 2013. Serum KL‐6 is a predictor of outcome in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tejwani D, Delacruz AE, Niazi M, et al. 2011. Unsuspected pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 5:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Canellas R, Daniel K, Henrique P, et al. 2012. Spontaneous regression of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Radiol. Bras. 45(5):294–296. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khan A, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. 2012. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in North India. Indian J. Chest Dis. Allied Sci. 54:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shende RP, Sampat BK, Prabhudesai P, et al. 2013. Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J. Assoc. Physicians India 61:209–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hammami S., Harrathi K, Lajmi K, et al. Congenital pulmonary alveolar proteinosis Case Rep. Pediatr. doi: 10.1155/2013/764216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Main S, Somani V, Molyneux A, et al. 2013. Unsuspected pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in a patient with a slow resolving pneumonia: a case report. Respir. Med. Case Reports. 10:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bansal A, and Sikri V 2013. A case of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis treated with whole lung lavage. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 17(5):314–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rojanapremsuk T, Arroyo JE, and Zepeda MR 2013. Case report and review of alveolar proteinosis. Lab Med. 44(2):147. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ishii H, Seymour JF, Tazawa R, et al. 2014. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis complicating myelodysplastic syndrome results in worsening of prognosis: a retrospective cohort study in Japan. BMC Pulm. Med. 14:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fijołek J, Wiatr E, Radzikowska E, et al. 2014. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis during a 30‐year observation. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 82:206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramirez J, Nyka W, McLaughlin J 1963. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: diagnostic technics and observations. N. Engl. J. Med. 268:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prakash U, Barhan S, Carpenter H, et al. 1987. Pulmonary alveolar phospholipoproteinosis: experience with 34 cases and a review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 62:499–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]