Abstract

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in vertebrate early development and morphogenesis. Duplin (axis duplication inhibitor) interacts with β-catenin and prevents its binding to Tcf, thereby inhibiting downstream Wnt signaling. Here we show that Duplin is expressed predominantly from early- to mid-stage mouse embryogenesis, and we describe the generation of mice deficient in Duplin. Duplin−/− embryos manifest growth retardation from embryonic day 5.5 (E5.5) and developmental arrest accompanied by massive apoptosis at E7.5. The mutant embryos develop into an egg cylinder but do not form a primitive streak or mesoderm. Expression of β-catenin target genes, including those for T (brachyury), Axin2, and cyclin D1, was not increased in Duplin−/− embryos, suggesting that the developmental defect is not simply attributable to upregulation of Wnt signaling caused by the lack of this inhibitor. These results suggest that Duplin plays an indispensable role, likely by a mechanism independent of inhibition of Wnt signaling, in mouse embryonic growth and differentiation at an early developmental stage.

Wnt proteins constitute a large family of cysteine-rich secreted ligands that control development in organisms ranging from nematodes to mammals (46). The intracellular signaling pathway triggered by Wnt is also evolutionarily conserved and regulates cellular proliferation and differentiation (5, 35, 46). In the absence of Wnt, casein kinase Iα (CKIα) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) target cytoplasmic β-catenin for degradation (19, 27, 50). Axin forms a complex with GSK-3β, CKIα, β-catenin, and the adenomatous polyposis coli protein, and it stimulates the CKIα-dependent and GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation of β-catenin (12, 19, 22, 24, 27). Phosphorylated β-catenin in turn forms a complex with Fbw1 (also known as β-TrCP/FWD1), a member of the F-box protein family, resulting in the degradation of β-catenin by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (25).

The binding of Wnt to its cell surface receptor, consisting of Frizzled, as well as lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) 5 and LRP6, triggers the accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm as a result of the inhibition by Dvl of β-catenin phosphorylation. The accumulated β-catenin is then translocated to the nucleus, where it binds to the transcription factor T-cell factor, or Tcf (also known as lymphoid-enhancer factor, or Lef), and thereby induces the expression of various genes (5, 18, 35). Several proteins in the nucleus that bind to Tcf regulate the formation of the β-catenin-Tcf-DNA complex. β-Catenin signaling is thus regulated in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

Groucho binds to Tcf and represses the expression of Tcf target genes (8). Drosophila CREB-binding protein interacts with Drosophila Tcf and reduces its affinity for Armadillo (Drosophila β-catenin) (43), but mammalian CREB-binding protein and the related protein p300 act synergistically with β-catenin to activate gene expression (16, 41). COOH-terminal binding protein also binds to Tcf and inhibits its transactivation activity (6). NEMO-like kinase associates directly with and phosphorylates Tcf, resulting in inhibition of the binding of the β-catenin-Tcf complex to DNA (20). Pontin52 and Reptin52, both of which are transcription factors that bind directly to β-catenin and the TATA-binding protein, also inhibit the transactivation activity of the β-catenin-Tcf complex (2, 3). In addition, XSox17 (Sox) binds to β-catenin and inhibits the induction of gene expression by the β-catenin-Tcf complex (51). Inhibitor of β-catenin and Tcf-4 (ICAT) binds to β-catenin, inhibits formation of the β-catenin-Tcf-DNA complex, and thereby negatively regulates Wnt signaling (40). Wnt signaling through Tcf thus appears to be inhibited by several mechanisms at the level of the β-catenin-Tcf complex in the nucleus.

Duplin (axis duplication inhibitor) was identified by yeast two-hybrid screening of a rat brain cDNA library with the PDZ domain of Dvl-1 as the bait (34). Duplin is a protein of 749 amino acids whose COOH-terminal region (residues 482 to 749) contains several clusters of basic residues and a nuclear localization signal. Duplin does not form a complex with Dvl in COS cells, but it binds directly to the region of β-catenin that includes the Armadillo repeats, resulting in inhibition of the interaction of β-catenin with Tcf-4. Although overexpression of Duplin does not inhibit Wnt-3a-dependent accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm, it does block the activation of Tcf-4 by Wnt-3a. Dorsal injection of Duplin mRNA into Xenopus embryos results in loss of the head, as well as inhibition of the expression of siamois, whose product mediates the effects of the Wnt signaling pathway on axis formation. Furthermore, Duplin inhibits Wnt-8-dependent or β-catenin-dependent formation of a secondary dorsal axis in Xenopus. It also inhibits siamois-dependent axis duplication and blocks the Wnt signaling pathway at an additional point downstream by affecting the expression of β-catenin target genes (26). The physiological function of Duplin has remained largely unclear, however.

To examine the biological importance of Duplin in mammalian development, we disrupted the corresponding gene by homologous recombination in the mouse. The development of Duplin-deficient animals was arrested at gastrulation, with the embryos manifesting massive apoptosis. Unexpectedly, the expression of β-catenin target genes was not increased in the mutant embryos, suggesting that the lack of Duplin did not result in the constitutive activation of Wnt signaling during embryogenesis. Our data suggest that Duplin is indispensable for normal mouse development probably as a result of its function independent of inhibition of Wnt signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunoblot analysis.

Embryonic stem (ES) cells and embryos from embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) to birth were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described previously (13) with polyclonal antibodies to Duplin and a monoclonal antibody to α-tubulin (TU-01; Zymed).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and then exposed to H2O2. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (45). Duplin riboprobes (sense and antisense) corresponding to the entire open reading frame of the cDNA were synthesized with a DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche). Embryos were examined with a dissection microscope.

Construction of a targeting vector and generation of Duplin−/− mice.

Cloned DNA corresponding to the Duplin locus was isolated from a 129/Sv mouse genomic library (Stratagene). The targeting vector was constructed by replacing a 13-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment of genomic DNA containing all Duplin exons with a PGK-lox-neo-poly(A) cassette. The vector thus contained 6.5- and 1.2-kb regions of homology located 5′ and 3′, respectively, relative to the neomycin resistance gene (neo). A PGK-tk-poly(A) cassette was ligated at the 5′ end of the targeting construct. The maintenance, transfection, and selection of ES cells were performed as described previously (31). The recombination event was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with a 0.5-kb PstI-XbaI fragment of genomic DNA that flanked the 3′ homology region as the probe (see Fig. 2A). The expected sizes of hybridizing fragments after digestion with BglII and EcoRV were 5.4 and 8.0 kb for the wild-type and mutant Duplin alleles, respectively. Mutant ES cells were microinjected into C57BL/6 mouse blastocysts, and the resulting male chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 females. Germ line transmission of the mutant allele was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Heterozygous offspring were intercrossed to produce homozygous mutant animals. For genotyping of embryos, DNA was extracted from whole embryos at E3.5 to E9.5 or from corresponding embryonic tissue removed from sections on microscope slides; the extracted DNA was then analyzed by the nested PCR with the primers PJL (5′-TGCTAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGACTG-3′), MN5 (5′-TATAGATTTCCTGTTTGATTTTCC-3′), RV1 (5′-AACTCCGTAACCATTTGTCTATTC-3′), KN11 (5′-ATGCTCCAGACTGCCTTGGGAAAA-3′), MN11 (5′-AAAGAATCACACTAGATCTAATCC-3′), and RV2 (5′-GAAACAATGTAAAACAGGCAAATG-3′). The present study conformed with the guidelines of Kyushu University for the care and use of laboratory animals.

FIG. 2.

Gene targeting of the mouse Duplin locus. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type Duplin allele, the targeting vector, and the mutant allele after homologous recombination. A 13-kb genomic fragment including all exons of Duplin was replaced by a loxP-neo cassette. Exons and the probe used for hybridization are denoted by open and filled boxes, respectively. Restriction sites: B, BamHI; B2, BglII; E5, EcoRV; H3, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI; X, XbaI. (B) Southern blot analysis with the probe shown in panel A of tail genomic DNA from the offspring of heterozygote crosses after digestion with BglII and EcoRV. The 5.4- and 8.0-kb bands corresponding to the wild-type and mutant alleles, respectively, are indicated.

Histopathology and immunostaining.

Embryos within their deciduae were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, embedded in paraffin, sectioned with a cryostat at a thickness of 3 μm, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Immunostaining was performed as described with a monoclonal antibody to β-catenin (C19220; Transduction Laboratories), polyclonal antibodies to brachyury (N-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), conductin/Axin2 (S-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin D1 (553; MBL), cyclin D2 (M-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or cyclin D3 (C-16; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immune complexes were detected with a HistoMouse-Plus kit (Zymed) or with biotinylated secondary antibodies (1/400 dilution), an ABC kit (Vector), and diaminobenzidine (Sigma). Sections were examined with a differential interference contrast microscope.

Culture of preimplantation embryos.

Heterozygous male and female mutant mice were bred to obtain wild-type (Duplin+/+), heterozygous (Duplin+/−), and homozygous mutant (Duplin−/−) embryos. The morning of the day on which a vaginal plug was detected was designated E0.5. Embryos at E3.5 were collected by flushing oviducts or the uterus with HEPES-buffered medium 2 (M2; Sigma). Blastocysts were cultured for 6 days in tissue culture dishes containing cES medium without leukemia inhibitory factor (Chemicon), and outgrowths were inspected daily and photographed to monitor their development.

Detection of apoptosis.

For the TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) assay, paraffin-embedded sections were treated with H2O2, permeabilized for 15 min at 37°C with proteinase K (20 μg/ml; Sigma), and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Gibco) and biotinylated dUTP (Boehringer). Labeled DNA was visualized with an ABC kit and diaminobenzidine. Sections were examined with a differential interference contrast microscope. Sections first treated with DNase (Wako) were used as a positive control. For a negative control, the transferase was omitted from the reaction mixture.

RESULTS

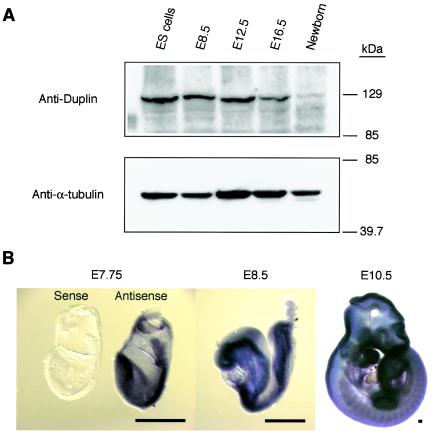

We first examined the expression of Duplin during mouse development by immunoblot analysis. Duplin was abundant both in ES cells (equivalent to E3.5) and in embryos at E8.5 and E12.5, but its expression was reduced at E16.5 and virtually undetectable in newborns (Fig. 1A). Duplin was also expressed in various adult mouse tissues at low levels (data not shown). The expression of Duplin during early mouse development was also examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Duplin mRNA was detected throughout embryos from E7.5 to E9.5 but was localized predominantly in the brains, faces, branchial arches, limb buds, and tail buds of embryos at E10.5 (Fig. 1B, and data not shown). These results suggest that Duplin function is largely restricted to the early to middle stage of mouse embryonic development.

FIG. 1.

Duplin expression during mouse development. (A) Immunoblot analysis of Duplin expression in wild-type ES cells (equivalent to E3.5), embryos (E8.5, E12.5, and E16.5), and newborn animals. The expression of α-tubulin was examined as a loading control. (B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of wild-type embryos at E7.75, E8.5, and E10.5 with a Duplin antisense riboprobe. The result of a control experiment with a sense riboprobe is shown for an E7.75 embryo. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Mouse Duplin is located on chromosome 14, spans ∼13 kb, and consists of nine exons (Fig. 2A). The binding site for β-catenin is encoded by exons 5 to 9. Mouse Duplin cDNA contains an open reading frame of 2,256 bp and shares 96 and 91% sequence identity with the corresponding rat and human cDNAs, respectively. To elucidate the function of Duplin during mouse development, we generated mice deficient in this protein by gene targeting. The targeting construct for the disruption of mouse Duplin was designed to delete all exons of the gene (Fig. 2A). ES cells were transfected with the linearized targeting vector, and recombinant clones were selected and injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Chimeric males that transmitted the mutant allele to the germ line were mated with C57BL/6 females, and the resulting heterozygotes were intercrossed to yield homozygous mutant mice. However, Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from 3-week-old mice revealed the absence of animals homozygous for the mutation (Fig. 2B). To date, no homozygous mutants have been detected among 88 newborn animals from heterozygote crosses, whereas heterozygous offspring appeared normal and fertile. To determine the time at which the Duplin mutation becomes lethal, we examined embryos from Duplin+/− intercrosses at various developmental stages. Most Duplin−/− embryos had been resorbed by E9.5; they were still recoverable at E8.5 (Table 1), however, although their growth appeared arrested (see Fig. 3).

TABLE 1.

Genotype of embryos from Duplin heterozygous intercrossesa

| Embryonic day | No. of animals of genotype:

|

Total no. of animals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− (no. abnormal) | ||

| E3.5 | 31 | 53 | 20 (0) | 104 |

| E5.5 | 1 | 3 | 1 (1) | 5 |

| E6.0 | 4 | 7 | 6 (6) | 17 |

| E6.5 | 8 | 21 | 2 (2) | 31 |

| E7.5 | 14 | 25 | 7 (7) | 46 |

| E8.5 | 3 | 3 | 1 (1) | 7 |

| E9.5 | 4 | 9 | 0 (0) | 13 |

| Newborn | 34 | 54 | 0 (0) | 88 |

Embryos from heterozygous intercrosses were dissected from sections under a microscope and genotyped according to the nested PCR strategy.

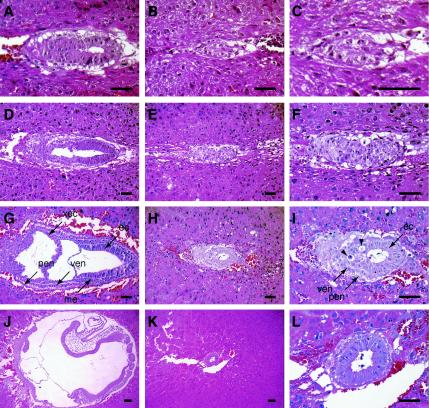

FIG. 3.

Histopathology of Duplin−/− embryos. The development of Duplin+/+ (A, D, G, and J) and Duplin−/− (B, E, H, and K) embryos is shown at E5.5, E6.5, E7.5, and E8.5, respectively. Higher-magnification views of the Duplin−/− embryos are also shown (C, F, I, and L). Arrowheads in panel I indicate apoptotic cells with condensed nuclei. Abbreviations: ec, ectoderm; me, mesoderm; pen, parietal endoderm; ven, visceral endoderm; xec, extraembryonic ectoderm. Scale bars, 100 μm.

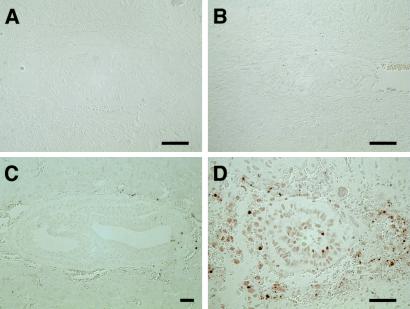

In contrast to wild-type embryos (Fig. 3A, D, G, and J), the growth of Duplin−/− embryos appeared retarded as early as E5.5 (Fig. 3B and C) and almost arrested after E6.5 (Fig. 3E, F, H, I, K, and L), although the wild type and the homozygous mutant appeared to be indistinguishable at the blastocyst stage (E3.5) (data not shown). Duplin−/− embryos developed into an egg cylinder consisting of two layers of tissue, ectoderm and visceral endoderm, at E7.5 (Fig. 3H and I), but formation of the primitive streak and mesoderm was not observed. Cells with condensed nuclei (Fig. 3I) and cells positive for TUNEL staining (Fig. 4D) were apparent in the ectoderm-like layer of Duplin−/− embryos at E7.5. Wild-type embryos at this stage contained few TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, we performed TUNEL assay in the wild type and in homozygous mutants at E6.0 when the first morphological changes can be detected (Fig. 4A and B). However, we failed to detect TUNEL-positive cells at this stage in the wild-type and mutant embryos (Fig. 4A and B), suggesting that the pronounced apoptosis apparent in Duplin−/− E7.5 embryos is a secondary effect of the developmental arrest.

FIG. 4.

Pronounced apoptosis in early Duplin−/− embryos. Sections of Duplin+/+ (A and C) and Duplin−/− (B and D) embryos at E6.0 (A and B) and E7.5 (C and D) were subjected to the TUNEL assay. Scale bars, 100 μm.

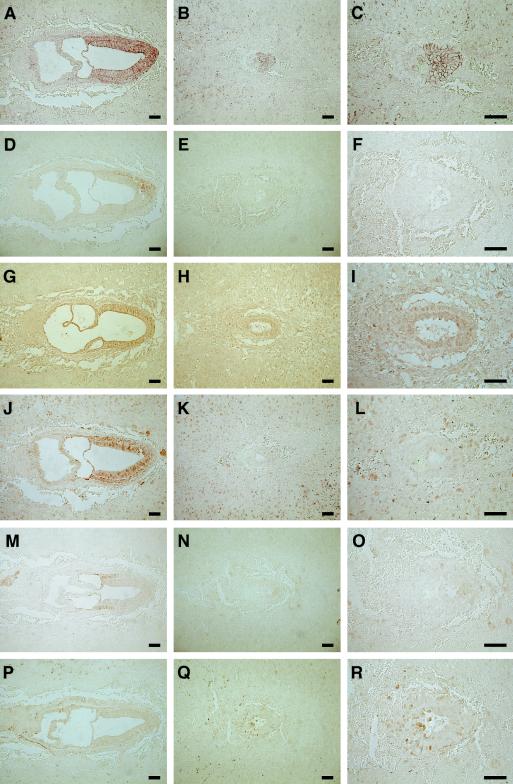

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that β-catenin was expressed predominantly at the intercellular adhesive surface in tissues of both wild-type and mutant embryos at E7.5 (Fig. 5A to C). We also examined the expression of the products of target genes of Wnt-β-catenin signaling, including T (brachyury), Axin2 (also known as Conductin or Axil), and D-type cyclins (D1, D2, and D3), by immunohistochemistry at E7.5. Brachyury is a transcription factor that contains a T box and regulates the balance between mesodermal and neural cell fates in the primitive streak during gastrulation and anteroposterior axis development (48). Brachyury was not detected in Duplin−/− embryos, whereas it was expressed in the primitive streak of wild-type embryos (Fig. 5D to F). Axin2 is a direct target and a major negative regulator of Wnt signaling pathway, which promotes the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin (4, 21, 29, 49). Axin2 was expressed in ectodermal and mesodermal cells in the wild-type embryos, whereas it was expressed in the ectoderm-like layer of Duplin−/− embryos (Fig. 5G to I). In wild-type embryos, cyclin D1 was expressed predominantly in ectodermal and mesodermal cells (Fig. 5J), whereas the expression of cyclin D2 was restricted to the mesoderm (Fig. 5M) and cyclin D3 expression was not detected in embryonic tissue but was apparent in the ectoplacental cone and extraembryonic endoderm (Fig. 5P). In contrast, none of the three D-type cyclins was detected in embryonic tissue of Duplin−/− mutants (Fig. 5K, L, N, O, Q, and R), although a low level of cyclin D3 expression was apparent in the ectoplacental cone and extraembryonic endoderm. The expression of downstream effectors of Wnt-β-catenin signaling was thus not increased, as might have been expected, in the absence of the inhibitor Duplin.

FIG. 5.

Reduced expression of the products of β-catenin target genes in Duplin−/− embryos. Sections of Duplin+/+ (A, D, G, J, M, and P) and Duplin−/− (B, E, H, K, N, and Q) embryos at E7.5 were subjected to immunohistochemistry with antibodies to β-catenin (A and B), to brachyury (D and E), to Axin2 (G and H), to cyclin D1 (J and K), to cyclin D2 (M and N), or to cyclin D3 (P and Q). Higher-magnification views of the Duplin−/− embryo sections are also shown (C, F, I, L, O, and R). Scale bars, 100 μm.

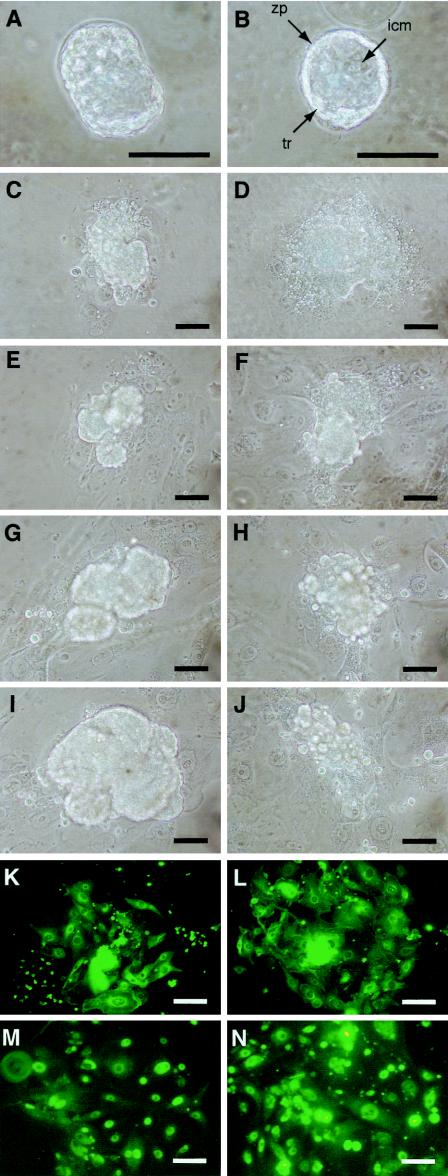

To assess directly the growth capability of Duplin−/− embryos, we collected E3.5 blastocysts from heterozygote intercrosses and cultured them individually in vitro for 6 days, during which time they formed outgrowths. Both Duplin+/+ and Duplin−/− blastocysts hatched, attached to the culture dish, and produced apparently normal trophoblast giant cells (Fig. 6), suggesting that Duplin−/− blastocysts can implant in the uterus. However, the inner cell mass of Duplin−/− embryos developed poorly and formed colonies incompletely after 4 to 5 days of culture (equivalent to E7.5 to E8.5) (Fig. 6F and H); it had collapsed and disappeared after 6 days of culture (equivalent to E9.5) (Fig. 6J), whereas the inner cell mass of Duplin+/+ blastocysts appeared to grow normally. This developmental phenotype of Duplin−/− embryos in vitro is consistent with that of mutant postimplantation embryos in vivo.

FIG. 6.

Defective outgrowth of Duplin−/− blastocysts in vitro. (A to J) Blastocysts from heterozygote intercrosses were cultured for 6 days. The development of Duplin+/+ (A, C, E, G, and I) and Duplin−/− (B, D, F, H, and J) blastocysts was examined at E5.5 (A and B), E6.5 (C and D), E7.5 (E and F), E8.5 (G and H), and E9.5 (I and J). (K to N) Outgrown Duplin+/+ (K and M) and Duplin−/− (L and N) blastocysts at E9.5 were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with antibodiesto β-catenin (K and L) or to cyclin D1 (M and N). Abbreviations: icm, inner cell mass; tr, trophoectoderm; zp, zona pellucida. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Immunostaining for β-catenin showed that this protein was localized to the perinuclear region and cytoplasm of trophoectodermal epithelial cells in both Duplin−/− and wild-type embryos after 6 days in culture (Fig. 6K and L). Furthermore, immunostaining for cyclin D1 revealed that this protein was largely restricted to the nucleus of trophoectodermal epithelial cells of both wild-type and Duplin−/− embryos at this time (Fig. 6M and N). These results also support the notion that the lack of Duplin does not simply result in abnormal activation of the Wnt signaling pathway.

DISCUSSION

Although several proteins that participate in the Wnt signaling pathway have been identified, the precise roles of these molecules in mammalian embryogenesis have remained unclear. Biochemical and genetic studies in Xenopus have shown that Duplin represses β-catenin-mediated transactivation and inhibits the Wnt signaling pathway. We thus expected that Wnt-β-catenin signaling would be constitutively activated in mice lacking Duplin, resulting in a phenotype characterized by developmental abnormality or carcinogenesis. Duplin−/− mice indeed died in utero at E7.5, suggesting that Duplin is essential for gastrulation during mouse development. In contrast to our expectations, however, Wnt signaling was not activated in the Duplin-deficient embryos, and these animals manifested massive apoptosis at death. Our data suggest two possibilities: (i) Duplin might not contribute to the Wnt signaling pathway but rather to some other functions or (ii) Duplin might function in both the Wnt signaling pathway and other ways, but the lack of the latter function results in an earlier or more severe phenotype than that of the former. Generation of conditional gene-targeted mice should provide insight into this question.

Vertebrate gastrulation begins with the formation of the primitive streak, which provides the first definition of the anteroposterior axis. Subsequently, some cells intercalate through the streak to emerge as a layer of mesoderm. Wnt signaling is important for definition of the anteroposterior axis. Inhibition of posteriorly localized Wnt signaling by anteriorly localized Wnt antagonists thus induces the formation of anterior structures, including the forebrain and heart, from neural ectoderm and mesoderm (47). Mice that lack β-catenin manifest a defect in anteroposterior axis formation at E5.5, do not form mesoderm or head structures, and show pronounced apoptosis at the time of death, which occurs at approximately E7.5 (17). These characteristics indicate that β-catenin is essential for formation of the anteroposterior axis. Of the various Wnt genes, Wnt3 is expressed earliest during development, its expression being apparent immediately before gastrulation (E6.25) in the proximal epiblast of the egg cylinder (28). Wnt3−/− mice develop a normal egg cylinder but do not form a primitive streak, mesoderm, or node. Between E6.5 and E8.5, the Wnt3−/− embryos continue to grow as an egg cylinder consisting of two layers of tissue: ectoderm and visceral endoderm. The developmental abnormalities of β-catenin-deficient embryos are apparent earlier and are more severe than those of the Wnt3−/− mutant, suggesting that another unknown Wnt protein might function earlier than does Wnt3 to establish the anteroposterior axis in mice. Alternatively, the β-catenin signaling pathway may be activated in mice by a process that does not require Wnt ligands, as is thought to be the case in amphibians (7). The phenotype of Duplin−/− mice, which do not form a primitive streak or mesoderm and arrest development at E7.5, is similar to that of β-catenin-deficient embryos, suggesting that Duplin might regulate β-catenin signaling in a Wnt-independent manner. Although β-catenin-null embryos show a defect in anteroposterior axis formation at E5.5, as visualized by marker gene expression, they are morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type embryos at this time (17). In contrast, Duplin−/− embryos already display a distinct morphology at E5.5, indicating that Duplin plays an indispensable role at a developmental stage earlier than that at which Wnt-β-catenin signaling regulates anteroposterior axis formation.

Many target genes of the Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway, including those for T (brachyury) (1, 48), Axin2 (also known as Conductin or Axil) (4, 21, 29, 49), cyclin D1 (36, 42), c-Myc (15), c-Jun, Fra-1 (30), and PPARδ (14), have been identified in mammals. In Duplin−/− mice, we expected that Wnt-β-catenin signaling would be constitutively activated, resulting in increased expression of these target genes. Previous analysis revealed that overexpression of Duplin did not affect the abundance or subcellular distribution of β-catenin (34). We also did not detect any obvious difference in the amount or subcellular localization of β-catenin between Duplin−/− and wild-type embryos, indicating that Duplin does not affect the stability or transport of β-catenin. With regard to β-catenin-mediated transactivation, expression of brachyury, Axin2, or D-type cyclins was not increased in Duplin−/− embryos at E7.5, suggesting that Duplin does not function as a negative regulator of Wnt-β-catenin signaling. The expression of brachyury, a mesodermal marker, and mesoderm formation were not observed in the mutant embryos, although it remains unclear whether these abnormalities are the cause or the result of embryonic death at this stage of development.

Axin2 and its ortholog Axin are negative regulators of the Wnt signaling pathway. During mouse embryogenesis, Axin is expressed ubiquitously, but Axin2 is expressed in a restricted pattern that overlaps with sites of Wnt signaling (21). In wild-type embryos, Axin2 was restricted to the ectoderm and the mesoderm, whereas it was expressed in the ectoderm-like layer of Duplin−/− embryos. Given that mesoderm formation is not observed in the mutant embryos, there is no substantial difference in the expression pattern between wild-type and mutant embryos. Furthermore, quantitative PCR revealed that the amount of Axin2 mRNA was not increased in Duplin−/− embryos (data not shown).

Three D-type cyclins have been identified and are expressed in different tissues in mammals (11, 37, 38). In addition to cyclin D1, cyclin D2 also controls cellular proliferation by acting downstream of Wnt-β-catenin signaling (23). Whereas the tissue-specific expression of D-type cyclins was apparent in wild-type embryos at E7.5, none of these proteins was expressed in Duplin−/− embryos at this time, suggesting that the cell cycle of individual cells was arrested and the embryos were already dead at this stage. We also did not detect the expression of cyclin D by immunohistochemistry from E5.5 to E6.5 in the mutant embryos (data not shown), suggesting that the failure to detect cyclin D was not simply the result of embryonic death.

The earlier onset, as well as the greater severity, of the developmental defect of Duplin−/− embryos compared to that of β-catenin-deficient mice suggested the possibility that Duplin might function to regulate basic cellular activities such as the cell cycle or apoptosis at an early developmental stage. Given also that Duplin−/− embryos died at E7.5 manifesting massive apoptosis, we performed TUNEL assay at earlier developmental stage, but we detected few apoptotic cells. These results suggest that apoptosis is induced after the stage when the first morphological changes can be detected. The apoptosis observed in the mutant embryos is likely the consequence of developmental arrest in Duplin−/− embryos. With regard to a link between Wnt signaling and apoptosis, cross talk between Wnt signaling and the p53 signaling pathway has been described (9, 10, 33). Overexpression of β-catenin thus resulted in accumulation of p53, whereas overexpression of p53 resulted in downregulation of β-catenin. In contrast, WISP-1 (Wnt-1-induced secreted protein), a target of Wnt-β-catenin signaling, has been shown to activate the antiapoptotic signaling pathway mediated by Akt (protein kinase B), as well as to prevent cells from p53-dependent apoptosis through inhibition of the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL (39). The phenotype of Duplin-deficient mice is more severe than that of mice lacking other regulators of apoptosis, such as caspases or members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins; the lack of these regulators often affects specific tissues at late stages of embryogenesis or even in adulthood (32, 44). What function either alone or together with defective Wnt signaling is responsible for the severe developmental abnormalities of Duplin−/− mice therefore remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Hatakeyama, T. Kamura, M. Shirane, Y. A. Minamishima, M. Yada, T. Hara, and Y. Kotake for valuable discussions and Y. Yamada and K. Shimoharada for technical assistance. We also thank A. Ohta and M. Kimura for help in preparing the manuscript.

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by the Yasuda Medical Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, S. J., J. Stappert, A. Bauer, A. Kispert, B. G. Herrmann, and R. Kemler. 2000. Brachyury is a target gene of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mech. Dev. 91:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer, A., S. Chauvet, O. Huber, F. Usseglio, U. Rothbacher, D. Aragnol, R. Kemler, and J. Pradel. 2000. Pontin52 and reptin52 function as antagonistic regulators of beta-catenin signalling activity. EMBO J. 19:6121-6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, A., O. Huber, and R. Kemler. 1998. Pontin52, an interaction partner of β-catenin, binds to the TATA box binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14787-14792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrens, J., B. A. Jerchow, M. Wurtele, J. Grimm, C. Asbrand, R. Wirtz, M. Kuhl, D. Wedlich, and W. Birchmeier. 1998. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with β-catenin, APC, and GSK3β. Science 280:596-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bienz, M., and H. Clevers. 2000. Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103:311-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brannon, M., J. D. Brown, R. Bates, D. Kimelman, and R. T. Moon. 1999. XCtBP is a XTcf-3 co-repressor with roles throughout Xenopus development. Development 126:3159-3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadigan, K. M., and R. Nusse. 1997. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 11:3286-3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavallo, R. A., R. T. Cox, M. M. Moline, J. Roose, G. A. Polevoy, H. Clevers, M. Peifer, and A. Bejsovec. 1998. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 395:604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damalas, A., A. Ben-Ze'ev, I. Simcha, M. Shtutman, J. F. Leal, J. Zhurinsky, B. Geiger, and M. Oren. 1999. Excess beta-catenin promotes accumulation of transcriptionally active p53. EMBO J. 18:3054-3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damalas, A., S. Kahan, M. Shtutman, A. Ben-Ze'ev, and M. Oren. 2001. Deregulated beta-catenin induces a p53- and ARF-dependent growth arrest and cooperates with Ras in transformation. EMBO J. 20:4912-4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantl, V., G. Stamp, A. Andrews, I. Rosewell, and C. Dickson. 1995. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev. 9:2364-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart, M. J., R. de los Santos, I. N. Albert, B. Rubinfeld, and P. Polakis. 1998. Downregulation of beta-catenin by human Axin and its association with the APC tumor suppressor, β-catenin and GSK3β. Curr. Biol. 8:573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatakeyama, S., M. Kitagawa, K. Nakayama, M. Shirane, M. Matsumoto, K. Hattori, H. Higashi, H. Nakano, K. Okumura, K. Onoe, R. A. Good, and K.-I. Nakayama. 1999. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IκBα is mediated by a ubiquitin ligase Skp1/Cul 1/F-box protein FWD1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3859-3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, T. C., T. A. Chan, B. Vogelstein, and K. W. Kinzler. 1999. PPARδ is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell 99:335-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, T. C., A. B. Sparks, C. Rago, H. Hermeking, L. Zawel, L. T. da Costa, P. J. Morin, B. Vogelstein, and K. W. Kinzler. 1998. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 281:1509-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hecht, A., K. Vleminckx, M. P. Stemmler, F. van Roy, and R. Kemler. 2000. The p300/CBP acetyltransferases function as transcriptional coactivators of β-catenin in vertebrates. EMBO J. 19:1839-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huelsken, J., R. Vogel, V. Brinkmann, B. Erdmann, C. Birchmeier, and W. Birchmeier. 2000. Requirement for β-catenin in anterior-posterior axis formation in mice. J. Cell Biol. 148:567-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurlstone, A., and H. Clevers. 2002. T-cell factors: turn-ons and turn-offs. EMBO J. 21:2303-2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda, S., S. Kishida, H. Yamamoto, H. Murai, S. Koyama, and A. Kikuchi. 1998. Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, forms a complex with GSK-3β and β-catenin and promotes GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation of β-catenin. EMBO J. 17:1371-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishitani, T., J. Ninomiya-Tsuji, S. Nagai, M. Nishita, M. Meneghini, N. Barker, M. Waterman, B. Bowerman, H. Clevers, H. Shibuya, and K. Matsumoto. 1999. The TAK1-NLK-MAPK-related pathway antagonizes signalling between β-catenin and transcription factor TCF. Nature 399:798-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jho, E. H., T. Zhang, C. Domon, C. K. Joo, J. N. Freund, and F. Costantini. 2002. Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1172-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi, A. 1999. Roles of Axin in the Wnt signalling pathway. Cell. Signal. 11:777-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kioussi, C., P. Briata, S. H. Baek, D. W. Rose, N. S. Hamblet, T. Herman, K. A. Ohgi, C. Lin, A. Gleiberman, J. Wang, V. Brault, P. Ruiz-Lozano, H. D. Nguyen, R. Kemler, C. K. Glass, A. Wynshaw-Boris, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 2002. Identification of a Wnt/Dvl/β-catenin → Pitx2 pathway mediating cell-type-specific proliferation during development. Cell 111:673-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishida, S., H. Yamamoto, S. Ikeda, M. Kishida, I. Sakamoto, S. Koyama, and A. Kikuchi. 1998. Axin, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of β-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10823-10826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitagawa, M., S. Hatakeyama, M. Shirane, M. Matsumoto, N. Ishida, K. Hattori, I. Nakamichi, A. Kikuchi, K.-I. Nakayama, and K. Nakayama. 1999. An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of β-catenin. EMBO J. 18:2401-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, M., S. Kishida, A. Fukui, T. Michiue, Y. Miyamoto, T. Okamoto, Y. Yoneda, M. Asashima, and A. Kikuchi. 2002. Nuclear localization of Duplin, a β-catenin-binding protein, is essential for its inhibitory activity on the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5816-5822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, C., Y. Li, M. Semenov, C. Han, G. H. Baeg, Y. Tan, Z. Zhang, X. Lin, and X. He. 2002. Control of β-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 108:837-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, P., M. Wakamiya, M. J. Shea, U. Albrecht, R. R. Behringer, and A. Bradley. 1999. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nat. Genet. 22:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lustig, B., B. Jerchow, M. Sachs, S. Weiler, T. Pietsch, U. Karsten, M. van de Wetering, H. Clevers, P. M. Schlag, W. Birchmeier, and J. Behrens. 2002. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1184-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann, B., M. Gelos, A. Siedow, M. L. Hanski, A. Gratchev, M. Ilyas, W. F. Bodmer, M. P. Moyer, E. O. Riecken, H. J. Buhr, and C. Hanski. 1999. Target genes of β-catenin-T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1603-1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama, K., N. Ishida, M. Shirane, A. Inomata, T. Inoue, N. Shishido, I. Horii, D. Y. Loh, and K. I. Nakayama. 1996. Mice lacking p27Kip1 display increased body size, multiple organ hyperplasia, retinal dysplasia, and pituitary tumors. Cell 85:707-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama, K. I., K. Nakayama, I. Negishi, K. Kuida, Y. Shinkai, M. C. Louie, L. E. Fields, P. J. Lucas, V. Stewart, F. W. Alt, and D. Y. Loh. 1993. Disappearance of the lymphoid system in Bcl-2 homozygous mutant chimeric mice. Science 261:1584-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadot, E., B. Geiger, M. Oren, and A. Ben-Ze'ev. 2001. Down-regulation of β-catenin by activated p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6768-6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto, I., S. Kishida, A. Fukui, M. Kishida, H. Yamamoto, S. Hino, T. Michiue, S. Takada, M. Asashima, and A. Kikuchi. 2000. A novel β-catenin-binding protein inhibits β-catenin-dependent Tcf activation and axis formation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32871-32878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidensticker, M. J., and J. Behrens. 2000. Biochemical interactions in the wnt pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1495:168-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shtutman, M., J. Zhurinsky, I. Simcha, C. Albanese, M. D'Amico, R. Pestell, and A. Ben-Ze'ev. 1999. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the β-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5522-5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sicinski, P., J. L. Donaher, Y. Geng, S. B. Parker, H. Gardner, M. Y. Park, R. L. Robker, J. S. Richards, L. K. McGinnis, J. D. Biggers, J. J. Eppig, R. T. Bronson, S. J. Elledge, and R. A. Weinberg. 1996. Cyclin D2 is an FSH-responsive gene involved in gonadal cell proliferation and oncogenesis. Nature 384:470-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sicinski, P., J. L. Donaher, S. B. Parker, T. Li, A. Fazeli, H. Gardner, S. Z. Haslam, R. T. Bronson, S. J. Elledge, and R. A. Weinberg. 1995. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell 82:621-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su, F., M. Overholtzer, D. Besser, and A. J. Levine. 2002. WISP-1 attenuates p53-mediated apoptosis in response to DNA damage through activation of the Akt kinase. Genes Dev. 16:46-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tago, K., T. Nakamura, M. Nishita, J. Hyodo, S. Nagai, Y. Murata, S. Adachi, S. Ohwada, Y. Morishita, H. Shibuya, and T. Akiyama. 2000. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by ICAT, a novel β-catenin-interacting protein. Genes Dev. 14:1741-1749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takemaru, K. I., and R. T. Moon. 2000. The transcriptional coactivator CBP interacts with β-catenin to activate gene expression. J. Cell Biol. 149:249-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tetsu, O., and F. McCormick. 1999. β-Catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature 398:422-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waltzer, L., and M. Bienz. 1998. Drosophila CBP represses the transcription factor TCF to antagonize Wingless signalling. Nature 395:521-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, J., and M. J. Lenardo. 2000. Roles of caspases in apoptosis, development, and cytokine maturation revealed by homozygous gene deficiencies. J. Cell Sci. 113:753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson, D. G., and M. A. Nieto. 1993. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol. 225:361-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wodarz, A., and R. Nusse. 1998. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14:59-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi, T. P. 2001. Heads or tails: Wnts and anterior-posterior patterning. Curr. Biol. 11:R713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi, T. P., S. Takada, Y. Yoshikawa, N. Wu, and A. P. McMahon. 1999. T (Brachyury) is a direct target of Wnt3a during paraxial mesoderm specification. Genes Dev. 13:3185-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan, D., M. Wiesmann, M. Rohan, V. Chan, A. B. Jefferson, L. Guo, D. Sakamoto, R. H. Caothien, J. H. Fuller, C. Reinhard, P. D. Garcia, F. M. Randazzo, J. Escobedo, W. J. Fantl, and L. T. Williams. 2001. Elevated expression of axin2 and hnkd mRNA provides evidence that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in human colon tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14973-14978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yost, C., M. Torres, J. R. Miller, E. Huang, D. Kimelman, and R. T. Moon. 1996. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of β-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 10:1443-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zorn, A. M., G. D. Barish, B. O. Williams, P. Lavender, M. W. Klymkowsky, and H. E. Varmus. 1999. Regulation of Wnt signaling by Sox proteins: XSox17α/β and XSox3 physically interact with β-catenin. Mol. Cell 4:487-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]