Abstract

Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) has distinct clinical characteristics in comparison to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). The genetic contribution is suggested to be more potent in EOAD. However, the frequency of causative mutations in EOAD could be variable depending on studies. Moreover, no mutation screening study has been performed yet employing large population in Korea. Previously, we reported that the rate of family history of dementia in EOAD patients was 18.7% in a nationwide hospital-based cohort study, the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of South Korea (CREDOS) study. This rate is much lower than in other countries and is even comparable to the frequency of LOAD patients in our country. To understand the genetic characteristics of EOAD in Korea, we screened the common Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mutations in the consecutive EOAD subjects from the CREDOS study from April 2012 to February 2014. We checked the sequence of APP (exons 16–17), PSEN1 (exons 3–12), and PSEN2 (exons 3–12) genes. We identified different causative or probable pathogenic AD mutations, PSEN1 T116I, PSEN1 L226F, and PSEN2 V214L, employing 24 EOAD subjects with a family history and 80 without a family history of dementia. PSEN1 T116I case demonstrated autosomal dominant trait of inheritance, with at least 11 affected individuals over 2 generations. However, there was no family history of dementia within first-degree relation in PSEN1 L226F and PSEN2 V214L cases. Approximately, 55.7% of the EOAD subjects had APOE ε4 allele, while none of the mutation-carrying subjects had the allele. The frequency of genetic mutation in this study is lower compared to the studies from other countries. The study design that was based on nationwide cohort, which minimizes selection bias, is thought to be one of the contributors to the lower frequency of genetic mutation. However, the possibility of the greater likeliness of earlier onset of sporadic AD in Korea cannot be excluded. We suggest early AD onset and not carrying APOE ε4 allele are more reliable factors for predicting an induced genetic mutation than the presence of the family history in Korean EOAD population.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mutation, presenilin, apolipoprotein-E, sequencing, early onset Alzheimer’s disease, genetics

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the devastating neurodegenerative disorders and the most frequent cause of dementia. AD is classified into late-onset AD (LOAD) and early-onset AD (EOAD) with the onset age of 65 years being the differentiating border.1 Although this partition was arbitrary having been based on the retirement age, accumulating evidence demonstrates distinct characteristics of EOAD in comparison to LOAD. The clinical progression of EOAD is more rapid, demonstrating frequent early non-amnesic deficits and intense behavioral, including psychotic, symptoms.1–4 The deterioration of functional connectivity of the neural networks is more extensive in EOAD, involving neocortex rather than being confined to medial temporal region from the earlier disease stage.5–7 Further, to the degree that EOAD affects the subjects who actively work, its social impact is more devastating, and because of this social and economic burden, EOAD needs additional attention.

The genetic contribution to AD pathogenesis is potent in EOAD. The familial occurrence is more frequent in EOAD compared to LOAD, ranging from 32% to 73.3% in referral centers.8–10 Also, the frequency of causative mutations in EOAD with autosomal dominant inheritance is much higher, although the frequency is variable between studies (from 11.8% to 71.0%).8,9,11 The rate of family history of dementia in first-degree relatives of Korean EOAD patients was similar to that of LOAD (18.7% vs 15.8%) in hospital-based cohort study.12 This rate is much lower than the incidents previously reported.11,13 The recent historical plight of Korea, including a 3-year nationwide war and sustained division of the country, is likely to confound the derivation of an accurate family history of dementia because of the lack of demographic information. To understand the genetic characteristics of EOAD in Korea, we screened the common AD mutations in EOAD subjects from the nationwide cohort, the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of South Korea (CREDOS) study.12

The aim of the current study was to estimate the frequency of causative known AD mutations in Korean EOAD patients through checking the mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes, including serially recruited 104 subjects with EOAD.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects who developed clinical symptoms of AD before 65 years of age were consecutively recruited from 8 institutes as a part of a hospital-based cohort study conducted by the CREDOS from April 2012 to February 2014. Comprehensive neurological, neuropsychological, laboratory, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluations were performed as previously described.12 All EOAD patients met the revised clinical criteria of probable AD from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA)14 at initial evaluation and follow-up. Blood samples were collected from 104 unrelated EOAD patients who gave written informed consent for this study. An attempt was made at establishing familial aggregation of pathogenic mutations in these patients with EOAD. The EOAD subjects showing pathologic mutations were investigated to determine whether or not the disease exhibited any familial aggregation. All protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of each hospital and were in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic analysiss

Genomic DNA was extracted from the leukocytes using commercially available Puregene kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The causative mutations of AD in the APP (exons 16–17), PSEN1 (exons 3–12), and PSEN2 (exons 3–12) genes along with the flanking intron sequences were screened, because the causative AD mutations are mainly located in these regions.15

Statistics

Two group comparisons between the subjects with and without a family history of dementia were performed using independent sample t-test (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS] Version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age at onset (AO) was 56.3±5.6 years. The family history of dementia was noted in 24 patients, among whom maternal history was observed in 19 (18.3%) and paternal history in 5 (4.9%) patients. There was no difference between the EOAD subjects with and without family history in terms of sex, AO, education, severity of dementia, mini-mental state examination, clinical dementia rating, and APOE genotype.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the subjects

| All (n=104) |

Family history (n=24) |

No family history (n=80) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, F | 63 (60.6%) | 17 (70.8%) | 46 (57.5%) |

| Age, years | 60±5.4 | 61.0±6.0 | 59.4±5.2 |

| Age at onset, years | 56.3±5.6 | 57.2±6.3 | 56.1±5.4 |

| Education, years | 9.0±4.5 | 9.3±4.8 | 9.0±4.5 |

| MMSE | 18±6.9 | 18.3±6.5 | 17.9±7.0 |

| CDR | 1.1±0.7 | 1.1±0.7 | 1.1±0.8 |

| CDR-SOB | 5.8±4.5 | 5.5±4.0 | 5.9±4.7 |

| APOE genotype | |||

| ε2ε3 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| ε3ε3 | 44 (42.3%) | 10 (41.7%) | 34 (42.5%) |

| ε3ε4 | 46 (44.2%) | 8 (33.3%) | 38 (47.5%) |

| ε4ε4 | 12 (11.5%) | 5 (20.8%) | 7 (8.8%) |

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Abbreviations: CDR, clinical dementia rating; CDR-SOB, clinical dementia rating-sum of boxes; F, female; MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Mutation analyses

Four AD causative mutations were identified when genetic mutations in APP (exons 16–17), PSEN1 (exons 3–12), and PSEN2 (exons 3–12) were investigated. Two mutations were noted in PSEN1 gene, T116I and L226F. Both were previously identified as causative mutations in AD in the Western countries,16,17 and another 2 were observed in PSEN2 gene, R62C and V214L (Table 2). V214L was reported as a probable pathogenic mutation in our country based on in silico analysis.18 In regards to PSEN2 R62C, there has been a report in relation to AD.19 However, its pathogenic connection with AD has been refuted by its identification in non-AD subjects.20,21 No mutations were identified in exons 16 and 17 of APP gene in our EOAD subjects.

Table 2.

The EOAD subjects with identified genetic mutations

| Mutation | Pathogenic | Sex/AO/APOE | FH | Presenting symptoms | MMSE/CDR at imaging | Imaging | CSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PSEN1 T116I |

Causative (La Bella et al17) | Female/38/ε2ε3 | Yes | Memory loss | 23/0.5 | MRI: atrophy in med T FDG-PET: ↓ met in bi T & P |

tTau/Aβ42, 4.53; pTau181/Aβ42, 0.43 |

|

PSEN1 L226F |

Causative (Zelanowski et al;16 Bagyinszky et al22) | Female/37/ε3ε3 | No | Memory loss | 21/1 | MRI: atrophy in med T & P FDG-PET: ↓ met in bi T & P |

ND |

|

PSEN2 R62C |

Unclear (Sleegers et al;21 Ertekin-Taner et al;20 Brouwers et al19) | Male/49/ε3ε3 | No | Obsessive compulsive behavior | 24/1 | MRI: diffuse atrophy SPECT: ↓ perfusion in F & T |

ND |

|

PSEN2 V214L |

Probably involved in disease (Youn et al18) | Female/54/ε3ε3 | No | Memory loss, anomia | 15/1 | MRI: atrophy in med T FDG-PET: ND |

tTau/Aβ42, 1.66; pTau181/Aβ42, 0.20 |

Abbreviations: EOAD, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease; AO, age at onset; bi, bilateral; CDR, clinical dementia rating; F, frontal; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography; FH, family history; med, medial; met, metabolism; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; ND, not done; P, parietal; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; T, temporal; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

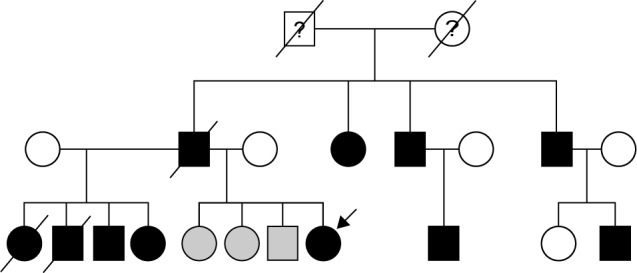

The EOAD patients with PSEN1 L226F do not have a family history of dementia. In the patient with PSEN2 V214L mutation, first-degree relatives did not have dementia, and only the grandmother was reported to have an unknown subtype of dementia at the age of 70 years. In contrast, subject with PSEN1 T116I mutation had paternal history of dementia with autosomal dominant trait (Figure 1). However, the family history for individuals of earlier generation was not available. Screening for genetic mutation in family members could be performed in PSEN1 L226F, both biological parents and 2 elderly siblings. They neither revealed clinical symptoms of dementia on evaluation nor carried the mutation at PSEN1, thus demonstrating that PSEN1 L226F in the patient is most likely from de novo mutation.22

Figure 1.

Genealogy tree of the EOAD patients with PSENl T1161 mutation. The symbols filled with black represent the patients with clinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the gray symbols correspond to the family members with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The arrow indicates the proband being studied here. The history of dementia was not available in first generation of the genealogy tree.

Abbreviation: EOAD, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The APOE genotype of the subjects was ε3ε3 in 3 subjects and ε2ε3 in 1 subject.

Discussion

In a study of 104 Korean EOAD patients, we identified 3 causative mutations by screening the genetic mutations in exons 16–17 of APP and coding regions of PSEN1 and PSEN2. This incidence was much lower compared to prior reports, where 71% (24 of 34 families with AO <61 years)11 and 54.6% (6 of 11 families with AO <65 years)9 of EOAD patients with autosomal dominant inheritance trait, and 68% of EOAD patients with a family history within first-degree relationship (21 of 31 probands with AO <61 years)23 were found to have a causative mutation in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP. A familial EOAD was defined as having one another EOAD patient within first-degree relationship with additional AD patient in this study, which is broader than the definition of autosomal dominant heritance, which requires 3 affections over 2 generations.24 Despite this, a causative mutation was found in only 1 case (4.2% of 24 familial cases). Most of the studies which reported higher frequency of genetic mutations were very likely to be influenced by the selection bias of including the subjects with genetic susceptibility.8 This recent investigation evaluating an unselected consecutive population over a 10-year period demonstrated that pathogenic mutations comprised 2 of 17 EOAD (11.8%, AO <65 years) cases with autosomal dominant inheritance.8 The Iberian African study recruited a larger number of unrelated EOAD patients regardless of family history from 9 different institutions (AO <65 years) and demonstrated a mutation frequency (6 of 74 familial EOAD patients) of 8.1%,10 in which the definition of family history was the same as ours. The frequency of genetic mutation from the recent unbiased screening studies is much closer to ours than the previously reported statistics. This study was conducted as a nationwide cohort study, and we tried to recruit every EOAD subject willing to give their consent and who met our inclusion criteria from April 2012 to February 2014. We believe that this approach minimizes the selection bias and is helpful in estimating the frequency of genetic mutation in the Korean EOAD population, and by extension in clinical practice.

There have been a few Asian studies on genetic screening of AD mutations. In a Japanese study, among 45 familial AD and 29 sporadic EOAD (AO <60 years) cases, 3 causative mutations were identified in EOAD patients (AO, 40–55 years) from 3 families (PSEN1 772A>G and PSEN1 1158C>A) and 1 sporadic case (PSEN2 1262C>T).25 A Chinese group screened AD mutations employing 54 familial EOAD (AO <65 years) cases from 32 families.26 Four PSEN1 (p.A434T, p.I167del, p.F105C, and p.L248P) mutations in 4, and 1 APP (p.V717I) mutation in 2 unrelated families were identified (AO, 33–50 years). All the recognized causative mutations were different from those observed in our study. An exact comparison of those results with ours is inappropriate due to the different design of the study. However, in terms of the frequency of mutation, our result of 1 in 24 familial EOAD cases is somewhat lower than the other Asian studies, while 2 in 80 EOAD cases without a family history of dementia is comparable.

There were only a few Korean studies on genetic screening or case reports of AD mutations. In 1996, Hong et al published a case report on PSEN1 H163R in a Korean family with EOAD, which is a quite common causative mutation for AD.27 In 2008, Park et al published a genetic screening study, but they employed only 6 EOAD patients. PSEN1 G206S and M233T and APP V715M causative mutations were found in 3 unrelated patients including 1 without family history.28 In 2010, Kim et al published a study on PSEN1 M139I in a family with EOAD.29 In 2012, a novel mutation, PSEN1 H163P, was reported in a probably de novo case of AD, which was suggested as a probable pathogenic variant associated with EOAD.30 The first PSEN2 mutation in Korea, PSEN2 V214L, was discovered in 2014, which was suggested to be involved in AD or another type of dementia due to three-dimensional (3D) modeling.18 Based on these studies, the authors raised the importance of genetic mutation screening in the Korean EOAD populations. We have, however, found 3 probable causative mutations among the 104 EOAD subjects. Thus, the specificity of presently available genetic screening technique in assessing EOAD patients is diminished. Hence, genetic screening techniques including more delicate guidelines are needed. Although we could not compute the statistical significance because of the small number of mutation cases, a positive family history seems not to be critical in predicting the presence of AD causative mutation in the Korean EOAD patients. We found 2 patients without an overt family history of a first-degree relative having had a genetic mutation, PSEN1 L226F and PSEN2 V214L, while only 1 patient in a familial case did note a recent Korean history, which impairs the precise tracking of family history of dementia. Instead, earlier AO was thought to be a more consistent factor in determining the necessity of checking genetic AD mutations in Korean EOAD patients. An AO of 58 years had been suggested as a cutoff point for genetic analysis based on Western data.9,23 AO was 31, 35, and 34 years in EOAD subjects with genetic mutation, and 62- and 55-year-old patients with AO did not carry causative mutations in a prior Korean study.28 Similarly, AO was 38, 37, and 54 years in our EOAD patients with causative mutation. Although we cannot provide the valuable cutoff age for genetic study in our population due to the low frequency of mutation, the AO threshold should be lower than in the Western countries.

Our prior cohort analysis demonstrated higher frequency of APOE ε4 allele in EOAD patients than in LOAD patients, since its occurrence was 49.3% vs 40.8%, respectively.12 Consistent with this finding, a Chinese study identified that 55.7% of the EOAD subjects had APOE ε4 allele. This was much higher than the reported allele frequency of APOE ε4 in EOAD patients from other countries.9,26 In contrast, none of the EOAD patients who were positive for causative mutation carried APOE ε4. These findings are consistent with prior reports demonstrating that the EOAD subjects carrying causative AD mutations are less likely to carry APOE ε4 allele.9,11 Taken together, not carrying APOE ε4 allele is suggested to be another factor to consider in the genetic mutation screening of EOAD. Additionally, the possibility is raised that EOAD in Korea is more likely to be an earlier manifestation of sporadic AD, based on the more prevalent APOE ε4 allele carriership in addition to the lower frequency of genetic mutation.31,32

We cannot exclude the likelihood that the protocol of genetic screening in this study might impair the additional detection of AD genetic mutations. The targeted sequencing of APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes including the sites with frequent AD causative mutations has been employed in prior genetic screening studies in EOAD. However, a recent study performing exome sequencing revealed that novel mutation is present in APP outside the common mutation sites.31 In the current study, we targeted part of APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 where most of the causative mutations were identified, which might miss the rare mutation of AD outside these regions, exons 10 and 12 of PSEN1 and exon 9 of PSEN2.33,34 Moreover, we could not check the copy number of APP, which might not detect genomic APP duplication.35 Thus, further study to perform exome sequencing may be helpful, since several additional genes were confirmed or suggested to be involved in AD progression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identified the 3 definitely or probably pathogenic AD mutations, PSEN1 T116I, PSEN1 L226F, and PSEN2 V214L, employing 24 EOAD patients with a family history and 80 without a family history of dementia. The frequency of such mutations was lower compared to the results reported from other countries. The study design having been based on a nationwide cohort minimizes the selection bias, thereby leading to a lower frequency of genetic mutation. However, the greater possibility of earlier onset of sporadic AD in Korea cannot be excluded. In addition, we suggest that earlier AO in the absence of APOE ε4 allele is more valuable in estimation of the necessity of genetic mutation testing than the presence of family history in Korean EOAD patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project (HI10C2020, HI14C1942, and HI14C3331) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), Korea Ministry of Health & Welfare, and the Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean Government (MSIP; No 2014M3C7A1064752). Genetic screening has been performed by Department of Bionano Technology, Gachon University. For the current study, blood samples were collected from the patients with informed consent at Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Republic of Korea; Dong-A University Medical Center, Busan, Republic of Korea; Gachon University, Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea; Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea; Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Ilsan Hospital, National Health Insurance Corporation, Goyang, Republic of Korea; Myongii Hospital, Goyang, Republic of Korea; Inha University School of Medicine, Incheon, Republic of Korea. The Ethical Committee of the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine & Neurocognitive Behavior Center, and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital approved the current study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):793–806. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panegyres PK, Chen HY, Coalition against major diseases (CAMD) Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: a global cross-sectional analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(9):1149–1154. doi: 10.1111/ene.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panegyres PK, Chen HY. Differences between early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2013;2(4):300–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho H, Jeon S, Kang SJ, et al. Longitudinal changes of cortical thickness in early- versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(7):1921.e9–1921.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adriaanse SM, Binnewijzend MA, Ossenkoppele R, et al. Widespread disruption of functional brain organization in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavedo E, Pievani M, Boccardi M, et al. Medial temporal atrophy in early and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(9):2004–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gour N, Felician O, Didic M, et al. Functional connectivity changes differ in early and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(7):2978–2994. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarmolowicz AI, Chen HY, Panegyres PK. The patterns of inheritance in early-onset dementia: Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;30(3):299–306. doi: 10.1177/1533317514545825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lleó A, Blesa R, Blesa R, et al. Frequency of mutations in the presenilin and amyloid precursor protein genes in early-onset Alzheimer disease in Spain. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1759–1763. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerreiro RJ, Baquero M, Blesa R, et al. Genetic screening of Alzheimer’s disease genes in Iberian and African samples yields novel mutations in presenilins and APP. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(5):725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(3):664–670. doi: 10.1086/302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park HK, Choi SH, Park SA, et al. Cognitive profiles and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Korean early-onset Alzheimer’s disease patients: a CREDOS study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(2):661–673. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Duijn CM, De Knijff P, Cruts M, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 allele in a population-based study of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 1994;7(1):74–78. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocchi A, Pellegrini S, Siciliano G, Murri L. Causative and susceptibility genes for Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Brain Res Bulletin. 2003;61(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zekanowski C, Golan MP, Krzyśko KA, et al. Novel presenilin 1 gene mutations connected with frontotemporal dementia-like clinical phenotype: genetic and bioinformatic assessment. Exp Neurol. 2006;200(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Bella V, Liguori M, Cittadella R, et al. A novel mutation (Thr116Ile) in the presenilin 1 gene in a patient with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11(8):521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Youn YC, Bagyinszky E, Kim H, Choi BO, An SS, Kim S. Probable novel PSEN2 Val214Leu mutation in Alzheimer’s disease supported by structural prediction. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Ann Med. 2008;40(8):562–583. doi: 10.1080/07853890802186905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ertekin-Taner N, Younkin LH, Yager DM, et al. Plasma amyloid beta protein is elevated in late-onset Alzheimer disease families. Neurology. 2008;70(8):596–606. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000278386.00035.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sleegers K, Roks G, Theuns J, et al. Familial clustering and genetic risk for dementia in a genetically isolated Dutch population. Brain. 2004;127(7):1641–1649. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagyinszky E, Park SA, Kim HJ, Choi SH, An SS, Kim SY. PSEN1 L226F mutation in a patient with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Korea. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1433–1440. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S111821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen JC, Beck JA, Campbell TA, et al. Early onset familial Alzheimer’s disease: mutation frequency in 31 families. Neurology. 2003;60(9):235–239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000042088.22694.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman JS, Younkin LH, Yager DM, et al. Comparison of family histories in FTLD subtypes and related tauopathies. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1817–1819. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187068.92184.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yagi R, Miyamoto R, Morino H, et al. Detecting gene mutations in Japanese Alzheimer’s patients by semiconductor sequencing. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(7):1780.e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao B, Tang B, Liu X, et al. Mutational analysis in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease in Mainland China. Neurobiol Aging. 1957;35(8):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong KS, Kim SP, Na DL, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of a pedigree of a thirty-six-year-old familial Alzheimer’s disease patient. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(12):1172–1176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HK, Na DL, Lee JH, Kim JW, Ki CS. Identification of PSEN1 and APP gene mutations in Korean patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(2):213–217. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Kim HY, Ki CS, Kim SH. Presenilin 1 gene mutation (M139I) in a patient with an early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: clinical characteristics and genetic identification. Neurol Sci. 2010;31(6):781–783. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Bagyinszky E, Chang YH, et al. A novel PSEN1 H163P mutation in a patient with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: clinical, neuroimaging, and neuropathological findings. Neurosci Lett. 2012;530(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sassi C, Guerreiro R, Gibbs R, et al. Exome sequencing identifies 2 novel presenilin 1 mutations (p.L166V and p.S230R) in British early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(10):2422.e13–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogaeva EA, Fafel KC, Song YQ, et al. Screening for PS1 mutations in a referral-based series of AD cases: 21 novel mutations. Neurology. 2001;57(4):621–525. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houlden H, Crook R, Backhovens H, et al. ApoE genotype is a risk factor in nonpresenilin early-onset Alzheimer’s disease families. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81(1):117–121. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980207)81:1<117::aid-ajmg19>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gómez-Tortosa E, Barquero S, Barón M, et al. Clinical-genetic correlations in familial Alzheimer’s disease caused by presenilin 1 mutations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(3):873–884. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, et al. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):24–26. doi: 10.1038/ng1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]