Abstract

Older adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) have poor survival. We examined the effectiveness of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) in adults with B-ALL age 55 years and older and explored prognostic factors associated with long-term outcomes.

Methods

Using CIBMTR registry data, we evaluated 273 patients (median age 61, range 55-72) with B-ALL with disease status in CR1 (71%), >CR2 (17%) and Primary Induction Failure (PIF)/Relapse (11%), who underwent RIC HCT between 2001-2012 using mostly unrelated donor (59%) or HLA-matched sibling (32%). Among patients with available cytogenetic data, the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+) was present in 50%.

Results

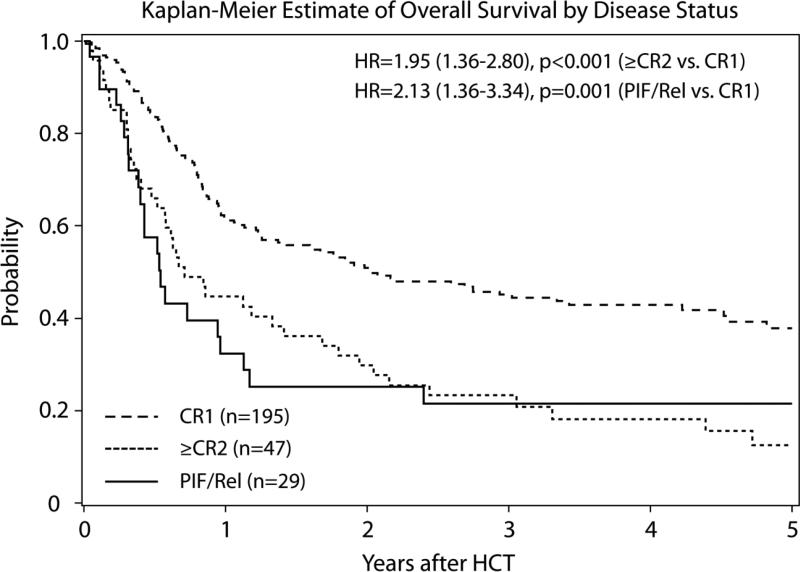

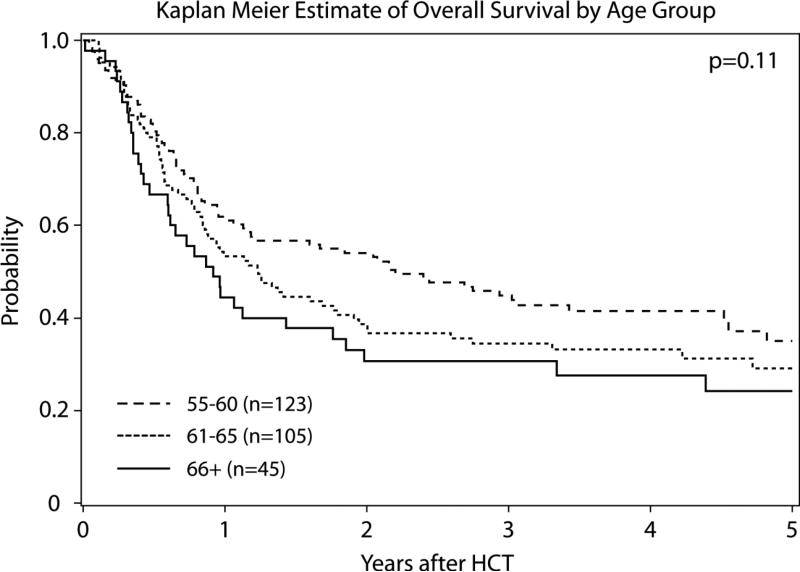

The 3-year cumulative incidences of non-relapse mortality (NRM) and relapse were 25% (95% confidence intervals (CI): 20-31%) and 47% (95% CI: 41-53%), respectively. Three-year overall survival (OS) was 38% (95% CI: 33-44%). Relapse remained the leading cause of death accounting for 49% of all deaths. In univariate analysis, 3 year risk of NRM was significantly higher with reduced Karnofsky performance status (KPS <90: 34% (95% CI: 25-43%) vs KPS ≥90 (18%; 95% CI: 12-24%, p=0.006). Mortality was increased in older adults (66+ vs. 55-60: Relative Risk (RR) 1.51 (95% CI: 1.00-2.29, p=0.05) and those with advanced disease (RR 2.13; 95% CI: 1.36-3.34, p=0.001). Survival of patients in CR1 yields 45% (95% CI: 38-52%) at 3 years and no relapse occurred after 2 years.

Conclusions

We report promising OS and acceptable NRM using RIC HCT in older patients with B-ALL. Disease status in CR1 and good performance status are associated with improved outcomes.

Keywords: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), Older adults, Reduced Intensity Conditioning (RIC), Hematopoietic Cell Transplant (HCT)

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are the largest ALL subset in which treatment advances have failed to improve outcomes.(1-3) ALL incidence is bimodal(4), it is estimated that 19% of patients diagnosed with ALL are over 55 years of age and this number will likely increase as the general population ages.(5) A recent population-based study of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data found that older adults (60 years and older) with B-ALL have 5 year survival rates of only 10% without improvements in the last 30 years.(2) Furthermore, few prospective trials enrolled patients 60 years or older and while remission rates range from 30-70%, the reported median survival varied from 9-14 months.(1, 3) Poorer outcomes among older adults can be partially explained by biological characteristics of ALL and their increased susceptibility to organ-toxicity and infections. Adverse disease characteristics such as the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+) t(9;22) increase with age where high risk cytogenetics are reported in half of adults 40 years and older.(3, 4, 6)

Recent advances in older adult B-cell ALL therapy have integrated intensive chemotherapy protocols with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) for Ph+ ALL. The inclusion of TKI therapy has led to high overall response rates allowing for more patients to proceed to allogeneic donor hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).(7-13) Allogeneic HCT has demonstrated Graft vs. Tumor effect and long term survival post HCT.(7, 14, 15) However, older age increases transplant-related mortality (TRM) among patients who receive myeloablative (MA) preparative regimens followed by HCT, mitigating a survival advantage.(16) Data from the CIBMTR indicate that 40% of adult transplants for hematologic malignancy now use reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens.(17) RIC HCT regimens allow for immune-mediated graft-versus-leukemia responses with potentially less toxicity, permitting allografts in older adults and in patients with reduced fitness or organ compromise. Criteria for decision making and recommendations regarding RIC HCT are unclear in older patients with ALL.(18) The contribution of chronologic age, treatment tolerance, comorbidities, ALL biology, and transplant procedure variables need to be studied to inform future treatment strategies. Using Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) data, we examined the transplant outcomes of patients 55 years or older who underwent RIC HCT for ALL and identified prognostic factors affecting non-relapse mortality, relapse, and overall survival.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

The CIBMTR® includes data from a voluntary working group of more than 450 transplant centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on allogeneic and autologous HCT. Participating centers are required to report all transplants consecutively; compliance is monitored by on-site audits and patients are followed longitudinally. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR's capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

The CIBMTR collects data at two levels: Transplant Essential Data (TED) level and Comprehensive Report Form (CRF) level. The TED-level data is an internationally accepted standard data set that contains a limited number of key variables for all consecutive transplant recipients. Details on CRF and TED level data collection have been previously published and are described in detail elsewhere.(19) TED and CRF level data are collected pre-transplant, 100 days and six months post-transplant, annually until year 6 post-transplant and biannually thereafter until death. Details of fungal infections, time to achievement of first complete remission (CR1), and cytogenetics were available for a nested cohort of 119 subjects with CRF reports.

Eligibility Criteria

We included all adults with B-cell ALL who were ≥55 years of age undergoing RIC HCT between 2001-2012 who had complete 100-day research form data. Patients at all disease stages CR1, CR2, and with advanced leukemia (defined as ≥CR3, primary induction failure (PIF), or relapsed disease) were included. Patients with T-cell ALL were excluded due to limited numbers (n=12). Two hundred and seventy-three cases met the selection criteria from 95 centers in 16 countries. RIC HCT regimens were defined in this protocol as containing busulfan ≤8mg/kg (orally) or ≤6.4mg/kg (intravenously), melphalan <150mg/m2, or low-dose total-body irradiation (fractionated TBI <8Gy or unfractionated TBI <5Gy).(20) All graft types were included. Donors were classified as HLA-matched sibling, HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUD), umbilical cord blood (UCB), or Other (HLA-mismatched unrelated and partially matched related).(21)

Outcomes

The primary outcome evaluated was overall survival (OS) which included death from any cause as an event. Secondary outcomes were non-relapse mortality (NRM) defined as death without evidence of leukemia recurrence and leukemia free survival (LFS) defined as the time from HCT to treatment failure (death or relapse). Leukemia relapse was defined as morphologic marrow or clinical extramedullary relapse after HCT. Acute graft versus host disease (aGVHD) was diagnosed and graded based on consensus criteria, and chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was diagnosed based on clinical criteria.(22, 23)

Statistical Methods

We describe the outcomes and important prognostic factors in adults ≥55 years with B-cell ALL utilizing retrospectively detailed information from the CIBMTR. Patient and transplant-related variables were compared using Chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the probability of OS and LFS. Cumulative incidence was used to estimate the probability of NRM, GVHD, and relapse. For GVHD and relapse, NRM was treated as a competing risk. Conversely, for NRM, relapse was treated as a competing risk. For LFS and OS patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina 2015) was used for all analyses. A univariate Cox regression analysis was carried out; despite having 300 cases, only 119 cases had complete information on cytogenetics and other covariates of importance precluding a multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

Patients, Disease, and Transplant Characteristics

We examined data on 273 patients from 95 reporting centers (Table 1). The median age was 61 years (range 55-72), and 56% had excellent performance status (KPS 90-100%). Most (n=195; 71%) patients were in CR1 and 45% of patients were <6 months from diagnosis. HCT conditioning most commonly utilized alkylating-based RIC (62% vs. 34% low dose TBI), peripheral blood stem cells (85%) T-replete grafts (69%). MUD were more common (n=104; 38%) than HLA-matched sibling donors (n=92; 34%) or UCB grafts (n=21; 8%). ‘Other’ grafts included partially matched unrelated donors (URD) (n=27), mismatched URD (n=2), matching unknown URD (n=18), and other related (includes haplo-identical) (n=9). In a nested cohort of 119 patients with detailed disease and patient characteristics, 50% had Ph+ chromosome, and 40% achieved CR1 within ≤8 weeks. Extramedullary disease at diagnosis (12%) and pre-transplant fungal infections (8%) were infrequent.

Table 1.

Patients, Disease, and Transplantation Characteristics

| Variable | Total N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients / centers | 273 / 95 | |||

| Gender | F: 141 (52) | |||

| Recipient age | Total N (%) | 55-60 | 61-65 | 66+ |

| Year of HCT | ||||

| 2001-2003 | 29 (11) | 12 (10) | 16 (15) | 1 (2) |

| 2004-2007 | 57 (21) | 28 (23) | 21 (20) | 8 (18) |

| 2008-2011 | 187 (68) | 83 (67) | 68 (65) | 36 (80) |

| Karnofsky score | ||||

| <=80 | 101 (37) | 45 (37) | 34 (32) | 22 (49) |

| 90-100 | 153 (56) | 69 (56) | 66 (63) | 18 (40) |

| Missing | 19 (7) | 9 (7) | 5 (5) | 5 (11) |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| 0 | 71 (26) | 29 (24) | 29 (28) | 13 (29) |

| 1 + | 117 (43) | 54 (44) | 39 (37) | 24 (53) |

| Earlier than 2007 | 73 (27) | 33 (27) | 33 (31) | 7 (16) |

| Missing | 12 (4) | 7 (6) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Disease status | ||||

| CR1 | 195 (71) | 92 (75) | 69 (66) | 34 (76) |

| >=CR2 | 47 (17) | 22 (18) | 19 (18) | 6 (13) |

| PIF/Rel | 29 (11) | 8 (7) | 17 (16) | 4 (9) |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Time from diagnosis to HCT | ||||

| <6 months | 123 (45) | 61 (50) | 43 (41) | 19 (42) |

| 6 - 12 months | 86 (32) | 30 (24) | 38 (36) | 18 (40) |

| >12 months | 64 (23) | 32 (26) | 24 (23) | 8 (18) |

| Median (range) | 7 (2-121) | 6 (2-85) | 7 (3-121) | 7 (4-43) |

| Conditioning regimen | ||||

| Low-dose TBI based (2Gy) | ||||

| TBI+Flu | 84 (31) | 35 (32) | 32 (29) | 17 (32) |

| TBI+other | 8 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Alkylating agent based | ||||

| Bu (≤8mg/kg po ≤6.4mg/kg IV) + Flu | 62 (23) | 27 (21) | 24 (23) | 11 (30) |

| Flu+Mel (<150mg/m2) | 80 (29) | 44 (34) | 30 (28) | 6 (16) |

| Cy+Flu | 15 (5) | 6 (5) | 7 (7) | 2 (5) |

| Other Alkylating agents | 13 (5) | 4 (3) | 5 (5) | 4 (11) |

| Other regimen | 11 (4) | 5 (4) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) |

| In-vivo T-cell depletion (ATG or campath) | ||||

| No | 189 (69) | 87 (71) | 69 (66) | 33 (73) |

| Yes | 83 (30) | 36 (29) | 35 (33) | 12 (27) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Graft type | ||||

| Bone marrow | 19 (7) | 7 (6) | 10 (10) | 2 (4) |

| Peripheral blood | 233 (85) | 105 (85) | 88 (84) | 40 (89) |

| Single UCB | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Double UCB | 17 (6) | 9 (7) | 5 (5) | 3 (7) |

| Type of donor | ||||

| Matched sibling | 92 (34) | 46 (37) | 36 (34) | 10 (22) |

| MUD | 104 (38) | 39 (32) | 41 (39) | 24 (53) |

| UCB | 21 (8) | 11 (9) | 7 (7) | 3 (7) |

| Other& | 56 (21) | 27 (22) | 21 (20) | 8 (18) |

| Prior fungal infections* | ||||

| No | 108 (91) | 47 (90) | 45 (94) | 16 (84) |

| Yes | 10 (8) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 3 (16) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Cytogenetics* | ||||

| t(9;22) present | 59 (50) | 31 (60) | 20 (42) | 8 (42) |

| t(9;22) absent | 33 (28) | 13 (25) | 14 (29) | 6 (32) |

| Missing | 27 (23) | 8 (15) | 14 (29) | 5 (26) |

| Extramedullary disease at diagnosis* | ||||

| No | 104 (87) | 46 (88) | 42 (88) | 16 (84) |

| Yes | 14 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (13) | 2 (11) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Time to achieve CR1* | ||||

| <=8 weeks | 48 (40) | 21 (40) | 21 (44) | 6 (32) |

| >8 weeks | 51 (43) | 22 (42) | 19 (40) | 10 (53) |

| N/A, CR1 not achieved | 5 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Missing | 15 (13) | 7 (13) | 6 (13) | 2 (11) |

| Median (range), weeks | 8 (2-57) | 8 (2-41) | 7 (2-57) | 11 (2-33) |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 49 (3-145) | 73 (3-145) | 61 (13-118) | 62 (20-74) |

Data limited to nested cohort of 119 subjects (55 centers)

Abbreviations: F: Female, HCT-CI: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant-Comorbidity Index, CR:Complete Remission, TBI: Total Body Irradiation, Flu: Fludarabine, Bu: Busulfaran, CsA: Cyclosporine, MTX:Methotrexate, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, MUD: matched unrelated donor, UCB: Umbilical Cord Blood, ATG: Anti-Thymocyte Globulin

mismatched unrelated donor and mismatched related(haplo=9)

Comparing three age groups (55-60 vs 61-65 vs 66+ years), disease status at HCT was similar (75% vs 66% vs 76% in CR1), but patients 66 years of age and older had worse KPS (<90%), more comorbidities, and were more likely to receive a MUD compared to younger patients (Table 1). Low-dose TBI /fludarabine conditioning regimen was common across age categories, whereas 66+ patients more often received busulfan/fludarabine. In a nested cohort of 119 patients with available cytogenetic data, Ph+ was more common in the 55-60 age group (n=31, 53%) and 80% Ph+ patients were in CR1 (n=47) compared to Ph− population. Yet other patient, disease, and transplant characteristics were similar among Ph+ and Ph− populations (Supplementary Table A).

Relapse and Non-Relapse Mortality

The cumulative incidences of relapse at 3 years was 47% (95% CI: 41% to 53%) and NRM was 25% (95% CI: 21% to 32%) (Supplementary Figure 1). Patients >66 years old had higher NRM (40%; 95%CI: 26% to 56%), while NRM was similar between patients 55-60 and 61-65 years old (23%; 22%; p=0.07; Table 2). KPS <90% led to a higher cumulative incidence of NRM; (34% (95% CI: 25% to 43%) vs. KPS ≥90%: 18% (95% CI: 12% to 24%); p=0.006). Relapse was more common in in-vivo T-cell depleted transplants 60% (95% CI: 49% to 70%); p=0.004. Three-year relapse rate tended to be lower among patients in CR1, but this did not reach statistical significance: CR1 43% (95% CI: 36% to 50%), >CR2 57% (95% CI: 43% to 71%), advanced disease 56% (95%CI 37% to 73%) (p=0.13). Type of conditioning (alkylator vs. low-dose TBI), donor source, GVHD prophylaxis, and year of HCT were not significantly associated with relapse or NRM (Table 2). In a nested cohort of 119 patients, we determined that history of prior fungal infection was associated with a 3-fold higher NRM (yes 67% (95% CI: 35% to 92%) vs. none 20% [95% CI: 13% to 28%], p=0.004}. Presence of Ph+ chromosome and delayed time to CR1 (>8 weeks) were not associated with relapse or NRM.

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidences of 3-Year Relapse and Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM)

| Relapse 3 yr | NRM 3 yr | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | N | Probability(95% CI) | p | Probability(95% CI) | p |

| Age in decades | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||

| 55-60 | 123 | 47 (38-56)% | 23 (15-31)% | ||

| 61-65 | 105 | 53 (43-62)% | 22 (14-30)% | ||

| 66+ | 45 | 33 (20-48)% | 40 (26-56)%ǂ | ||

| Karnofsky score | 0.30 | 0.006 | |||

| <=80 | 101 | 43 (33-53)% | 34 (25-43)% | ||

| 90-100 | 153 | 50 (42-58)% | 18 (12-24)% | ||

| Disease status | 0.13 | 0.72 | |||

| CR1 | 195 | 43 (36-50)% | 24 (18-30)% | ||

| >=CR2 | 47 | 57 (43-71)%ǂ | 28 (16-41)%ǂ | ||

| PIF/Rel | 29 | 56 (37-73)%ǂ | 30 (14-48)%ǂ | ||

| Conditioning regimen | 0.90 | 0.44 | |||

| Low-dose TBI based | 92 | 45 (35-55)% | 28 (19-37)% | ||

| Alkylating agent based | 170 | 48 (40-56)% | 23 (17-30)% | ||

| Other | 11 | 50 (21-79)%ǂ | 40 (13-70)%ǂ | ||

| Type of donor | 0.65 | 0.44 | |||

| Matched sib | 92 | 49 (39-60)% | 20 (12-29)% | ||

| MUD | 104 | 44 (34-53)% | 26 (18-35)% | ||

| UCB | 21 | 57 (36-77)%ǂ | 25 (9-46)%ǂ | ||

| Other& | 56 | 45 (32-58)%ǂ | 33 (21-46)%ǂ | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | 0.81 | 0.48 | |||

| CsA/tacrolimus + MTX | 104 | 48 (38-58)% | 21 (13-29)% | ||

| CsA/tacrolimus + MMF | 117 | 45 (36-54)% | 28 (20-36)% | ||

| Other | 49 | 51 (36-65)%ǂ | 25 (14-39)%ǂ | ||

| In-vivo T-cell depletion | 0.004 | 0.73 | |||

| No | 189 | 41 (34-48)% | 26 (20-32)% | ||

| Yes | 83 | 60 (49-70)%ǂ | 24 (15-34)% | ||

| Year of HCT | 0.41 | 0.99 | |||

| 2000-2006 | 73 | 51 (39-63)% | 25 (16-36)% | ||

| 2007-2012 | 200 | 45 (38-53)% | 25 (19-32)% | ||

| Prior fungal infections* | 0.21 | 0.004 | |||

| No | 107 | 54 (44-63)% | 20 (13-28)% | ||

| Yes | 10 | 33 (8-65)%ǂ | 67 (35-92)%ǂ | ||

| Cytogenetics* | 0.75 | 0.95 | |||

| t(9;22) present | 58 | 54 (41-67)% | 22 (12-34)%ǂ | ||

| t(9;22) absent | 33 | 58 (40-74)%ǂ | 23 (10-39)%ǂ | ||

| Time to achieve CR1* | 0.16 | 0.84 | |||

| <=8 weeks | 47 | 41 (28-56)% | 27 (15-41)%ǂ | ||

| >8 weeks | 51 | 60 (46-73)%ǂ | 22 (12-34)%ǂ |

Data limited to nested cohort of 119 subjects (55 centers)

Abbrevations: HCT-CI: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant-Comorbidity Index, CR: Complete Remission, TBI: Total Body Irradiation, Flu: Fludarabine, Bu: Busulfaran, CsA: Cyclosporine, MTX: Methotrexate, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, MUD: matched unrelated donor, UCB: Umbilical Cord Blood, ATG: Anti-Thymocyte Globulin

mismatched (haplo=9)

Less than 15 cases at risk at 3 years

Leukemia Free Survival and Overall Survival

LFS and OS at 3 years were 28% (95% CI: 23 to 34) and 38% (95% CI: 33 to 44), respectively (Supplementary Figure 2). Patients in CR1 at HCT had improved OS compared to higher overall mortality of patients in CR2 (RR 1.95 95% CI: 1.36 to 2.80; p=<0.001) or with advanced disease (RR 2.13 95% CI: 1.36 to 3.34; p=0.001) (Figure 1A). A univariate Cox regression model demonstrated that RIC HCT yielded similar survival rates among patients aged 55-60 and 61-65 years (RR 1.27; 95% CI: 0.92 to 1.75; p=0.15), but increased mortality in the 45 patients aged 66 years or above (RR 1.51; 95% CI: 1.00 to 2.29; p=0.05) (Figure 1B). LFS was significantly inferior in patients who were in CR2 (RR 1.75 95% CI: 1.21 to 2.54; p=0.003) or who had advanced disease (RR 1.99 95% CI: 1.33 to 2.99; p<0.001) at HCT; yet, age and KPS were not associated with LFS. Survival was not impacted by the conditioning regimen type, year of HCT, donor type, CMV matching, or type of GVHD prophylaxis (Table 3). In the nested cohort, history of fungal infections, as well as disease risk factors such as presence of Ph+ or time to CR1 were not associated with survival. The cumulative incidences of grade II-IV aGVHD, grade III-IV aGVHD, and cGVHD were similar in each of the three age groups (Supplementary Table B). The main cause of death across all age categories was disease relapse followed by infections and GVHD (Supplementary Table C).

Figure 1A.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival by disease status

Figure 1B.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival by age group

Table 3.

Univariate Cox Regression of LFS and OS

| Treatment failure (inversion of LFS) | Overall Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | N | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Age in decades | |||||

| 55-60 | 123 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 61-65 | 105 | 1.04 (0.76-1.42) | 0.80 | 1.27 (0.92-1.75) | 0.15 |

| 66+ | 45 | 1.15 (0.76-1.73) | 0.51 | 1.51 (1.00-2.29) | 0.05 |

| Karnofsky score | |||||

| <=80 | 101 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 90-100 | 153 | 0.85 (0.63-1.14) | 0.28 | 0.78 (0.57-1.07) | 0.13 |

| Disease status | |||||

| CR1 | 195 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| >=CR2 | 47 | 1.75 (1.21-2.54) | 0.003 | 1.95 (1.36-2.80) | < 0.001 |

| PIF/Rel | 29 | 1.99 (1.33-2.99) | < 0.001 | 2.13 (1.36-3.34) | 0.001 |

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| Low-dose TBI based | 92 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Alkylating agent based | 170 | 0.85 (0.63-1.14) | 0.29 | 1.08 (0.79-1.49) | 0.62 |

| Other | 11 | 1.32 (0.66-2.64) | 0.44 | 2.18 (1.11-4.27) | 0.02 |

| Type of donor | |||||

| Matched sib | 92 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| MUD | 104 | 1.02 (0.73-1.43) | 0.90 | 1.23 (0.87-1.75) | 0.24 |

| UCB | 21 | 1.39 (0.81-2.38) | 0.23 | 0.96 (0.51-1.79) | 0.89 |

| Other | 56 | 1.29 (0.87-1.92) | 0.20 | 1.43 (0.94-2.17) | 0.09 |

| CMV match | |||||

| Recipient negative | 90 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Recipient positive | 167 | 1.01 (0.74-1.36) | 0.97 | 1.09 (0.79-1.50) | 0.61 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |||||

| CsA/tacrolimus + MTX | 104 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| CsA/tacrolimus + MMF | 117 | 1.18 (0.86-1.62) | 0.30 | 1.04 (0.74-1.44) | 0.84 |

| Other | 49 | 1.14 (0.76-1.70) | 0.52 | 1.27 (0.84-1.91) | 0.26 |

| Year of HCT | |||||

| 2000-2006 | 73 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 2007-2012 | 200 | 0.83 (0.60-1.14) | 0.25 | 0.78 (0.56-1.08) | 0.13 |

| Prior fungal infection* | |||||

| No | 108 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 1.27 (0.63-2.55) | 0.50 | 1.55 (0.77-3.11) | 0.22 |

| Cytogenetics* | |||||

| t(9;22) present | 59 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| t(9;22) absent | 33 | 1.07 (0.66-1.74) | 0.77 | 1.10 (0.66-1.86) | 0.71 |

| Time to achieve CR1* | |||||

| <=8 weeks | 48 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| >8 weeks | 51 | 1.29 (0.82-2.02) | 0.27 | 1.48 (0.91-2.39) | 0.11 |

Examined in nested cohort of 119 patients

LFS: Leukemia-free survival; OS: overall survival, CI: confidence interval, HR: hazard ratio, MUD: matched unrelated donor; UCB: umbilical cord blood, CMV: cytomegalovirus, GVHD:graft-versus-host disease, HCT:hematopoietic cell transplantation, CSA: cyclosporine, MTX: methotrexate, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, CR: complete remission

RIC HCT in CR1

The subset of 195 RIC HCT recipients who were transplanted in CR1 with median age 61 years (range 55-72) had 3-year survival rates of 45% (95% CI: 38% to 52%). A univariate Cox regression model demonstrated that NRM in patients 55-60 and 61-65 years old was significantly lower (19%; 21%) compare to 41% (95% CI: 25% to 58%) in patients older than 66 years (p=0.05) yielding better survival among patients aged 55-60 compared to >66 years old (overall mortality HR 1.69; 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.76; p=0.04). Relapse was more common in in-vivo T-cell depleted transplants 56% (95% CI: 42% to 69%); p=0.004 (Supplementary Table D).

DISCUSSION

We report a large recent registry cohort of RIC HCT recipients ≥55 years old with B-cell ALL and a variety of donor sources. We report OS of 38% at 3 years and NRM of 25% for this patient population. Comparing reported outcomes in older adults with ALL undergoing transplant is difficult due to bias in age selection for RIC vs. MAC,(24, 25) differences in graft sources,(26) overlap in operational definitions for RIC vs. non-myeloablative conditioning,(27-29) and variable disease control at the time of transplant.(24) Therefore we sought to examine several prognostic factors that will aid the clinician in a decision making strategy for older adults with ALL.

One of the main findings of our study is the prognostic impact of disease status at the time of transplant on survival reflecting the recognized unfavorable biology of older adult ALL.26,27 The decision to proceed with transplant in CR1 is associated with improved survival of 45% at 3 years and long term disease control with few relapses beyond 2 years, which suggests graft-versus-leukemia effect delivered by RIC HCT. In contrast to increasing age, which was not associated with the risk of relapse, patients in CR2 or with advanced disease treated with RIC HCT as a salvage option were twice as likely to experience treatment failure across all age cohorts and disease relapse was by far the leading cause of death after HCT. These data mitigate the concern that HCT in CR1 is risky particularly for highly functional older adults, and is an opportunity for cure as others have reported.(30) Interestingly, nearly half of evaluable patients were Ph+ and HCT outcomes were quite similar in both groups. Lack of data on tyrosine-kinase inhibitors use before and after transplant limits our data interpretation, nevertheless most transplants occurred in era when TKI were largely available. Recent registry study showed that 41% of patients with Ph+ ALL undergoing RIC HCT were MRD negative pre-HCT and about a third received post-HCT TKI(10).

Nearly a quarter of older adults with ALL with intention to proceed to transplant actually undergo transplant, reflecting the heterogeneity in treating older adults with ALL and selection bias of transplant studies.(31) Importantly, we found that aging adults with B-ALL tolerate RIC with acceptable outcomes. Although we identified that aging patients have similar NRM, we also report that NRM is higher with poor performance status by univariate analysis. Notably, the observed association of older age (above 65 years) and impaired KPS limits our conclusions and signifies the need to incorporate validated prognostic tools to assess functional status prior to transplant.(32, 33) One major limitation of our study is that comorbidity data are incomplete for a third of the population and a comprehensive geriatric assessment was not performed routinely at HCT evaluation. A composite score of age and comorbidities can predict NRM and survival in HCT recipients (34) yet the interaction of age, co-existing disease and functional status are complex and dynamic. The transplant decision-making process can benefit from using validated assessment tools to predict the risk of toxicity in older adults with cancer. (32, 35-40) It is important to recognize that chronologic age should not be a deterrent for a bone marrow transplant evaluation. Full intensity conditioning has been reported to have significantly higher NRM among patients above 40 years of age thus considerably limiting the benefit of allografting; nevertheless the age in which RIC HCT should be considered for ALL is not well established.(10, 16, 41) Our data showed acceptable NRM for older ALL patients, and we hypothesize that performance status is the driving force for morbidity and mortality related to RIC transplant. While HCT in older patients with ALL is feasible and yield long-term survival, these outcomes may be improved by more careful patient selection. For example, our data albeit limited by small sample, suggest that prior fungal infection may be associated with mortality risk and could represent an additional concern prior to a planned HCT.

Alternative treatment strategies should be explored for patients in >CR2. The availability of novel and less toxic therapies and better diagnostic methods offers an opportunity to deepen remissions prior to allogeneic transplant. Whether novel therapies currently under development will provide safer, more effective treatment options for older adults with B-ALL is an important area for further study. Increased availability of the alternative donor pool (42, 43) and advances in supportive care continues to extend curative RIC HCT to selected eligible patients of all ages with acceptable organ function and performance status. Our results suggest that type of donor (matched sibling, MUD, umbilical cord blood, or mismatched donors) does not significantly influence transplant outcomes. Although the sample sizes were small, alternative graft sources may be particularly relevant for elderly adults who lack suitable HLA-matched sibling donors and deserve future studies. Consistent with others, we observed that in vivo T-cell depleted grafts were associated with more relapse, suggesting a potential approach to minimize relapse, although we are limited by small sample size and univariate analysis to imply deleterious effects on survival. Furthermore, the future transplant decision making process may also be guided by minimal residual disease (MRD) status, where it has been shown that patients with evidence of MRD who undergo transplant have longer relapse free survival, compared to non-transplant approach.(44) MRD may identify incipient relapse and permit either earlier transplant or novel therapies (45, 46) to deepen response while preparing for an allograft. Ultimately, age and conventional cytogenetics in prognostication should be supplemented for advances such as routine use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment,(32) MRD evaluation,(44) molecular analyses and/or genomic profiling.(44, 47)

In conclusion, our results provide the clinician with data to support decision making regarding the use of RIC HCT in older adults with ALL. While age should not limit access to RIC HCT, functional status should be carefully assessed and enrollment to clinical trials or alternative therapies should be sought for patients not in CR1. Clinical trials prospectively testing RIC in older adult ALL such as United Kingdom ALL XIV (UKALL14) are needed to inform on future directions in this challenging disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

CIBMTR Support List

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-15-1-0848 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Alexion; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Be the Match Foundation; *Bluebird Bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cellular Dynamics International, Inc.; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Genzyme Corporation; *Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Jeff Gordon Children's Foundation; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Merck & Co, Inc.; Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. – Japan; PCORI; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc; *Sanofi US; *Seattle Genetics; *Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick's Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; University of Minnesota; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

*Corporate Members

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional Contributing Authors:

Ibrahim Aldoss, Samer Al-Homsi, Mahmoud Aljurf, Edwin Alyea, George Ansstas, Ulrike Bacher, Karen Ballen, Fredric Baron, Amer Beitinjaneh, Claudio G. Brunstein, Michale Byrne, Jean-Yves Cahn, Mitchell Cairo, Jan Cerny, George Chen, Yi-Bin Chen, Stefan Ciurea, Edward Copelan, Corey Cutler, Zachariah DeFilipp, Abhinav Deol, Miguel Angel Diaz, Haydar Frangoul, Cesar Freytes, Manish Gandhi, Siddhartha Ganguly, Biju George, Usama Gergis, Michael Grunwald, Betty Ky Hamilton, Nancy Hardy, Shahrukh Hashmi, Mark Hertzberg, Gerhard Hildebrandt, Nasheed Hossain, William Hwang Ying Khee, Yoshi Inamoto, Madan Jagasia, Antonio Jimenez, Mark Juckett, Rammurti Kamble, Christopher Kanakry, Neena Kapoor, Partow Kebriaei, Nandita Khera, John Koreth, Mary Laughlin, Jan Liesveld, Mark Litzow, Marlise Luskin, Alan Miller, Guru Murthy, Ryotaro Nakamura, Rajneesh Nath, Maxim Norkin, Richard F. Olsson, Betul Oran, Jacob Passweg, Attaphol Pawarode, Miguel Angel Perales, Michael Pulsipher, Muthalagu Ramanathan, Walid K. Rasheed, Ran Rashef, David Rizzieri, Jacob Rowe, Ayman Saad, Bipin Savani, Gary Schiller, Sachiko Seo, Brian C. Shaffer, Melody Smith, Gerard Socie, Robert Soiffer, Robert Stuart, Jeffrey Szer, Celalettin Ustun, Geoffrey Uy, Koen Van Besien, Leo Verdonck, Ravi Vij, Edmund K. Waller, Matthew Wieduwilt, Peter Wiernik, Mona Wirk, William Allen Wood, Jean Yared, Agnes Yong

References

- 1.Rowe JM, Buck G, Burnett AK, Chopra R, Wiernik PH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, Franklin IM, Litzow MR, Ciobanu N, Prentice HG, Durrant J, Tallman MS, Goldstone AH, Ecog, Party MNALW Induction therapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of more than 1500 patients from the international ALL trial: MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2005;106:3760–3767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H. Improvement in survival in younger patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia from the 1980s to the early 21st century. Blood. 2009;113:1408–1411. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okasha D KA, Copland M, Lawrie E, McMillan A, Menne TF, et al. Fludarabine, Melphalan and Alemtuzumab Conditioned Reduced Intensity (RIC) Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Adults Aged >40 Years with De Novo Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Prospective Study from the UKALL14 Trial (ISRCTN 66541317)[abstract]. Blood. 2015:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moorman AV, Chilton L, Wilkinson J, Ensor HM, Bown N, Proctor SJ. A population-based cytogenetic study of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:206–214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program ( www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database.

- 6.Herold T, Baldus CD, Gokbuget N. Ph-like Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Older Adults. New Engl J Med. 2014;371:2235–2235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1412123#SA1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Buck G, Foroni L, Gerrard G, Litzow MR, Lazarus H, Luger SM, Marks DI, McMillan AK, Moorman AV, Patel B, Paietta E, Tallman MS, Goldstone AH. UKALLXII/ECOG2993: addition of imatinib to a standard treatment regimen enhances long-term outcomes in Philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:843–850. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-529008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassan R, Rossi G, Pogliani EM, Di Bona E, Angelucci E, Cavattoni I, Lambertenghi-Deliliers G, Mannelli F, Levis A, Ciceri F, Mattei D, Borlenghi E, Terruzzi E, Borghero C, Romani C, Spinelli O, Tosi M, Oldani E, Intermesoli T, Rambaldi A. Chemotherapy-phased imatinib pulses improve long-term outcome of adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Northern Italy Leukemia Group protocol 09/00. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3644–3652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Kim YJ, Min CK, Kim HJ, Eom KS, Kim DW, Lee JW, Min WS, Kim CC. The effect of first-line imatinib interim therapy on the outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2005;105:3449–3457. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachanova V, Marks DI, Zhang MJ, Wang H, de Lima M, Aljurf MD, Arellano M, Artz AS, Bacher U, Cahn JY, Chen YB, Copelan EA, Drobyski WR, Gale RP, Greer JP, Gupta V, Hale GA, Kebriaei P, Lazarus HM, Lewis ID, Lewis VA, Liesveld JL, Litzow MR, Loren AW, Miller AM, Norkin M, Oran B, Pidala J, Rowe JM, Savani BN, Saber W, Vij R, Waller EK, Wiernik PH, Weisdorf DJ. Ph+ ALL patients in first complete remission have similar survival after reduced intensity and myeloablative allogeneic transplantation: impact of tyrosine kinase inhibitor and minimal residual disease. Leukemia. 2014;28:658–665. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanada M, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, Akiyama H, Usui N, Yagasaki F, Kobayashi T, Ueda Y, Takeuchi M, Miyawaki S, Maruta A, Emi N, Miyazaki Y, Ohtake S, Jinnai I, Matsuo K, Naoe T, Ohno R, Japan Adult Leukemia Study G High complete remission rate and promising outcome by combination of imatinib and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a phase II study by the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:460–466. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, Beelen DW, Beck J, Stelljes M, Bornhauser M, Reichle A, Perz J, Haas R, Ganser A, Schmid M, Kanz L, Lenz G, Kaufmann M, Binckebanck A, Bruck P, Reutzel R, Gschaidmeier H, Schwartz S, Hoelzer D, Ottmann OG. Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Blood. 2006;108:1469–1477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delannoy A, Delabesse E, Lheritier V, Castaigne S, Rigal-Huguet F, Raffoux E, Garban F, Legrand O, Bologna S, Dubruille V, Turlure P, Reman O, Delain M, Isnard F, Coso D, Raby P, Buzyn A, Cailleres S, Darre S, Fohrer C, Sonet A, Bilhou-Nabera C, Bene MC, Dombret H, Berthaud P, Thomas X. Imatinib and methylprednisolone alternated with chemotherapy improve the outcome of elderly patients with Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the GRAALL AFR09 study. Leukemia. 2006;20:1526–1532. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiwaki S, Inamoto Y, Imamura M, Tsurumi H, Hatanaka K, Kawa K, Suzuki R, Miyamura K. Reduced-intensity versus conventional myeloablative conditioning for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in complete remission. Blood. 2011;117:3698–3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Chung NG, Cho BS, Eom KS, Kim YJ, Kim HJ, Min CK, Cho SG, Kim DW, Lee JW, Min WS, Park CW, Kim CC. Donor-specific differences in long-term outcomes of myeloablative transplantation in adults with Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:2110–2119. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, Tallman MS, Buck G, Fielding AK, Burnett AK, Chopra R, Wiernik PH, Foroni L, Paietta E, Litzow MR, Marks DI, Durrant J, McMillan A, Franklin IM, Luger S, Ciobanu N, Rowe JM. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111:1827–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eapen M, Logan BR, Horowitz MM, Zhong XB, Perales MA, Lee SJ, Rocha V, Soiffer RJ, Champlin RE. Bone Marrow or Peripheral Blood for Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Unrelated Donor Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:364–U203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamadani M, Craig M, Awan FT, Devine SM. How we approach patient evaluation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2010;45:1259–1268. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munker R, Wang HL, Brazauskas R, Saber W, Weisdorf DJ. Allogeneic Transplant for Acute Biphenotypic Leukemia: Characteristics and Outcome in the CIBMTR Database. Biol Blood Marrow Tr. 2015;21:S83–S83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, Apperley J, Slavin S, Pasquini M, Sandmaier BM, Barrett J, Blaise D, Lowski R, Horowitz M. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weisdorf D, Spellman S, Haagenson M, Horowitz M, Lee S, Anasetti C, Setterholm M, Drexler R, Maiers M, King R, Confer D, Klein J. Classification of HLA-matching for retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplantation: revised definitions to predict survival. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, Thomas ED. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone marrow transplantation. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, Hackman R, Tsoi MS, Storb R, Thomas ED. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. The American journal of medicine. 1980;69:204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohty M, Labopin M, Volin L, Gratwohl A, Socie G, Esteve J, Tabrizi R, Nagler A, Rocha V, Acute Leukemia Working Party of E Reduced-intensity versus conventional myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2010;116:4439–4443. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-266551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eom KS, Shin SH, Yoon JH, Yahng SA, Lee SE, Cho BS, Kim YJ, Kim HJ, Min CK, Kim DW, Lee JW, Min WS, Park CW, Lee S. Comparable long-term outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning versus myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adult high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia in complete remission. American journal of hematology. 2013;88:634–641. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanamori H, Mizuta S, Kako S, Kato H, Nishiwaki S, Imai K, Shigematsu A, Nakamae H, Tanaka M, Ikegame K, Yujiri T, Fukuda T, Minagawa K, Eto T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Morishima Y, Suzuki R, Sakamaki H, Tanaka J. Reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients aged 50 years or older with B-cell ALL in remission: a retrospective study by the Adult ALL Working Group of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2013;48:1513–1518. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Bacigalupo A, Horowitz M, Pasquini M, Sandmaier B. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:367–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacigalupo A. Second EBMT Workshop on reduced intensity allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplants (RI-HSCT). Bone marrow transplantation. 2002;29:191–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeMaistre CF, Farnia S, Crawford S, McGuirk J, Maziarz RT, Coates J, Irwin D, Martin P, Gajewski JL. Standardization of terminology for episodes of hematopoietic stem cell patient transplant care. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19:851–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forman SJ, Rowe JM. The myth of the second remission of acute leukemia in the adult. Blood. 2013;121:1077–1082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-234492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barba P, Martino R, Martinez-Cuadron D, Olga G, Esquirol A, Gil-Cortes C, Gonzalez J, Fernandez-Aviles F, Valcarcel D, Guardia R, Duarte RF, Hernandez-Rivas JM, Abella E, Montesinos P, Ribera JM. Impact of transplant eligibility and availability of a human leukocyte antigen-identical matched related donor on outcome of older patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2015;56:2812–2818. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1014365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muffly LS, Boulukos M, Swanson K, Kocherginsky M, Cerro PD, Schroeder L, Pape L, Extermann M, Van Besien K, Artz AS. Pilot study of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in allogeneic transplant: CGA captures a high prevalence of vulnerabilities in older transplant recipients. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood WA, Le-Rademacher J, Syrjala KL, Jim H, Jacobsen PB, Knight JM, Abidi MH, Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Geller NL, Rizzo JD, Fei M, Wu J, Horowitz MM, Lee SJ. Patient-reported physical functioning predicts the success of hematopoietic cell transplantation (BMT CTN 0902). Cancer. 2016;122:91–98. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorror ML, Storb RF, Sandmaier BM, Maziarz RT, Pulsipher MA, Maris MB, Bhatia S, Ostronoff F, Deeg HJ, Syrjala KL, Estey E, Maloney DG, Appelbaum FR, Martin PJ, Storer BE. Comorbidity-age index: a clinical measure of biologic age before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3249–3256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildes TM, Stirewalt DL, Medeiros B, Hurria A. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies in Older Adults: Geriatric Principles in the Transplant Clinic. J Natl Compr Canc Ne. 2014;12:128–136. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Extermann M, Falandry C, Artz A, Brain E, Colloca G, Flamaing J, Karnakis T, Kenis C, Audisio RA, Mohile S, Repetto L, Van Leeuwen B, Milisen K, Hurria A. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients With Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, Kritchevsky SB, Williamson JD, Pardee TS, Ellis LR, Powell BL. Geriatric assessment predicts survival for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:4287–4294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:1824–1831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, Magnuson A, Lowenstein L, Pandya C, O'Donovan A, Gorawara-Bhat R, Dale W. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2015;13:1120–1130. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP, Lichtman SM, Gajra A, Bhatia S, Katheria V, Klapper S, Hansen K, Ramani R, Lachs M, Wong FL, Tew WP. Predicting Chemotherapy Toxicity in Older Adults With Cancer: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marks DI, Wang T, Perez WS, Antin JH, Copelan E, Gale RP, George B, Gupta V, Halter J, Khoury HJ, Klumpp TR, Lazarus HM, Lewis VA, McCarthy P, Rizzieri DA, Sabloff M, Szer J, Tallman MS, Weisdorf DJ. The outcome of full-intensity and reduced-intensity conditioning matched sibling or unrelated donor transplantation in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2010;116:366–374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Ballanti S, Felicini R, Falcinelli F, Velardi A, Ruggeri L, Aloisi T, Saab JP, Santucci A, Perruccio K, Martelli MP, Mecucci C, Reisner Y, Martelli MF. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: A phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishiwaki S, Miyamura K, Ohashi K, Kurokawa M, Taniguchi S, Fukuda T, Ikegame K, Takahashi S, Mori T, Imai K, Iida H, Hidaka M, Sakamaki H, Morishima Y, Kato K, Suzuki R, Tanaka J, Cell JSH. Impact of a donor source on adult Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective analysis from the Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Working Group of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24:1594–1602. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhedin N, Huynh A, Maury S, Tabrizi R, Beldjord K, Asnafi V, Thomas X, Chevallier P, Nguyen S, Coiteux V, Bourhis JH, Hichri Y, Escoffre-Barbe M, Reman O, Graux C, Chalandon Y, Blaise D, Schanz U, Lheritier V, Cahn JY, Dombret H, Ifrah N, group G. Role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in adult patients with Ph-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:2486–2496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599894. quiz 2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gokbuget N, Goebeler M, Klinger M, Neumann S, Horst HA, Raff T, Viardot A, Schmid M, Stelljes M, Schaich M, Degenhard E, Kohne-Volland R, Bruggemann M, Ottmann O, Pfeifer H, Burmeister T, Nagorsen D, Schmidt M, Lutterbuese R, Reinhardt C, Baeuerle PA, Kneba M, Einsele H, Riethmuller G, Hoelzer D, Zugmaier G, Bargou RC. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, Martinelli G, Kantarjian H, Liedtke M, Stock W, Goekbuget N, Wang K, Pacagnella L, Sleight B, Vandendries E, Advani AS. Efficacy and Safety of Inotuzumab Ozogamicin (Ino) Vs Standard of Care (Soc) in Salvage 1 or 2 Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (All): An Ongoing Global Phase 3 Study. Haematologica. 2015;100:337–337. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Redefining ALL classification: toward detecting high-risk ALL and implementing precision medicine. Blood. 2015;125:3977–3987. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-580043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.