Abstract

The recent discovery of reversible mRNA methylation has opened a new realm of post-transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. The identification and functional characterization of proteins that specifically recognize RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) unveiled it as a modification that cells utilize to accelerate mRNA metabolism and translation. N6-adenosine methylation directs mRNAs to distinct fates by grouping them for differential processing, translation and decay in processes such as cell differentiation, embryonic development and stress responses. Other mRNA modifications, including N1-methyladenosine (m1A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and pseudouridine, together with m6A form the epitranscriptome and collectively code a new layer of information that controls protein synthesis.

RNA from all living organisms can be post-transcriptionally modified by a collection of more than 100 distinct chemical modifications1. Among these modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) has been identified as the most abundant internal modification in eukaryotic mRNA since its discovery in the 1970s2–7. In early experiments, radioactive labelling of methylation sites in mRNAs revealed that internal regions harboured significant radioactivity2,3 in addition to 5′ caps. These internal regions were later characterized as primarily m6A; the remaining fraction included 5-methylcytosine (m5C)7,8. RNA m6A is widely conserved across plants9–12 and vertebrates2,3,13–18, and is also found in viruses19–23 as well as in single-cell organisms such as archaea24,25, bacteria26 and yeast27 (Supplementary information S1 (box)). The amount of m6A in isolated RNA is estimated to constitute 0.1–0.4% of all adenosine nucleotides in mammals18,28, 0.7–0.9% of adenine nucleotides (all within GA dinucleotides) in meiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae29, and 1–15 sites per virion RNA molecule in various viruses30. Mutation and in vitro enzymatic studies have identified a consensus motif of RRm6ACH ([G/A/U][G>A]m6AC[U>A>C])31–34. However, owing to the low abundance of m6A in mRNA and the lack of effective techniques, functional characterizations of m6A have been largely absent over the past few decades.

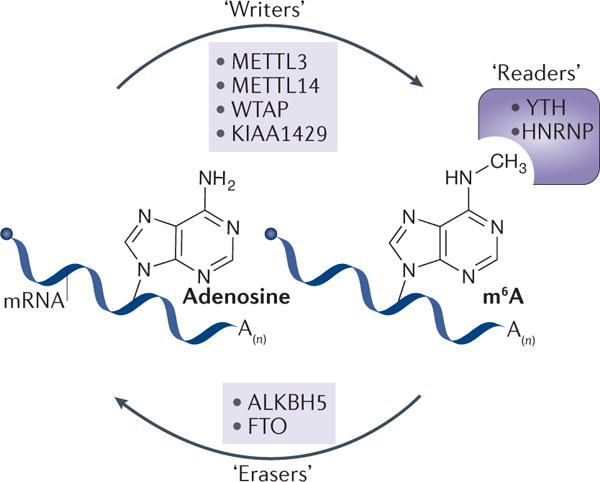

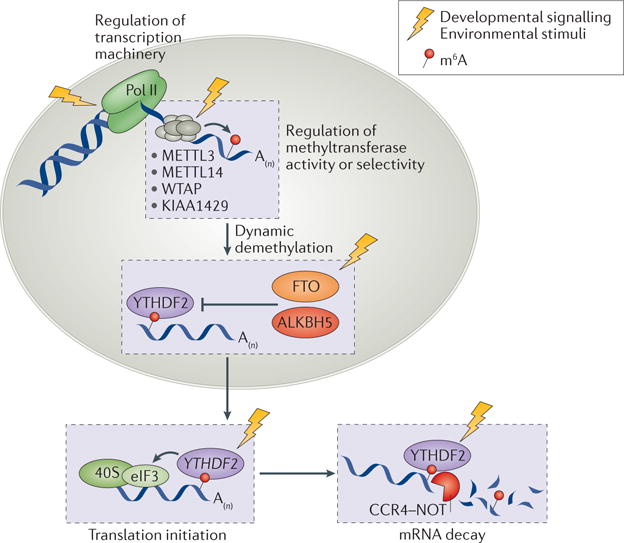

The deposition of m6A is carried out by a multicomponent methyltransferase complex that was first reported in 1994 (REF. 35). A key protein, methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), was subsequently identified as an S- adenosyl methionine-binding protein with methyltransferase capacity36. Recent studies have identified other components of the m6A methyltransferase complex in mammals, including METTL14 (REFS 37,38), Wilms tumour 1-associated protein (WTAP)37,39 and KIAA1429 (REF. 40) (FIG. 1). Homologues of human WTAP have been identified in yeast (MUM2)41 and in plants (FKBP12-interacting protein 37 (FIP37))12. In 2010, we speculated that RNA modifications such as m6A in mRNA could be dynamic and reversible42. This hypothesis was confirmed in 2011 with the discovery of the first m6A demethylase43, which rekindled interest in the biological relevance of m6A. The removal of m6A is facilitated by fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5)43,44 (FIG. 1), with each possessing distinct subcellular and tissue distributions44–48 and potentially affecting different subsets of target mRNAs. The demonstration that both these enzymes can catalyse the demethylation of m6A in mRNA43,44 provided the first evidence of reversible post-transcriptional modification in RNA transcribed by RNA polymerase II, including mRNAs and certain non-coding RNAs.

Figure 1. The writer, eraser and reader proteins of m6A.

The deposition, removal and recognition of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) are carried out by cognate factors termed writers, erasers and readers, respectively. Mammalian m6A writers function as a protein complex with four identified components so far: methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14, Wilms tumour 1-associated protein (WTAP) and KIAA1429. Two m6A erasers have been reported: fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5). The function of m6A is mediated partly by reader proteins, which have been identified in members of the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing protein and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP) protein families.

Following the use of a m6A-specific antibody to identify m6A sites in S. cerevisiae29, m6A-specific antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing to generate transcriptome-wide maps of m6A, charting the m6A epitranscriptome49,50. These studies have uncovered the presence of more than 10,000 m6A sites in over 25% of human transcripts, with enrichment in long exons, near stop codons and in 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs). 5′ UTRs and regions surrounding the start codon have also been shown to harbour varied levels of m6A in different species or cell types, or in certain growth conditions49,51,52. These observations confirmed that m6A is a prevalent modification in mRNA and confirmed its presence in the consensus sequence RRm6ACH. Many other m6A detection methods have since been developed, including advances in single-nucleotide resolution mapping and high-resolution characterization53–56 (reviewed in REFS 57,58).

Proteins that mediate the effects of m6A have also been uncovered (see below), together establishing a complex interplay among m6A deposition, removal and recognition factors (‘writers’, ‘erasers’ and ‘readers’, respectively)59. Writers and erasers determine the prevalence and distribution of m6A, whereas readers mediate m6A-dependent functions. The YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family of proteins (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3 and YTHDC1) are direct readers of m6A and have a conserved m6A-binding pocket49,60–65. In addition, the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP) proteins HNRNPA2B1 and HNRNPC selectively bind m6A-containing mRNAs66,67. HNRNPC recognizes m6A-induced changes in mRNA secondary structures67, whereas the exact mechanism for selective m6A binding by HNRNPA2B1 remains to be elucidated.

The writers, erasers and readers impart the biological functions of m6A (TABLE 1). Recent work has uncovered molecular mechanisms of m6A-dependent control of mRNA fate, along with its biological consequences. In this Review, we discuss the advances in our understanding of the biological effects of this prevalent mRNA modification. We propose a role for m6A in sorting groups of mRNAs for accelerated metabolism through the activity of reader proteins, which then affects numerous biological processes such as cell differentiation and development. Furthermore, we discuss additional mRNA chemical modifications that have potential roles in post-transcriptional gene regulation.

Table 1.

m6A regulators in humans

| Protein | Functional classification | m6A-associated biological function(s) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) | Catalytic subunit of m6A methyltransferase | Installs m6A; promotes translation independently of its catalytic activity | 36, 37, 89 |

| Methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) | A core subunit of m6A methyltransferase | A key component for m6A installation | 37 |

| Wilms tumour 1-associated protein (WTAP) | Regulatory subunit of m6A methyltransferase | Facilitates m6A installation | 37,39 |

| KIAA1429 | Regulatory subunit of m6A methyltransferase | Facilitates m6A installation | 40 |

| Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) | m6A demethylase | mRNA splicing, translation and adipogenesis | 43,52, 81,98 |

| AlkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5) | m6A demethylase | mRNA nuclear processing, mRNA export, promotes stemness phenotype of breast cancer stem cells | 44,52, 99 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1) | m6A reader | mRNA splicing, miRNA biogenesis | 66 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (HNRNPC) | m6A reader that recognizes m6A-induced structural changes | m6A structural switch, mRNA splicing | 67 |

| YTH domain-containing 1 (YTHDC1) | Direct m6A reader | mRNA splicing, transcriptional silencing | 62,63, 184 |

| YTH m6A-binding protein 1 (YTHDF1) | Direct m6A reader | Translation initiation | 60,61 |

| YTH m6A-binding protein 2 (YTHDF2) | Direct m6A reader | mRNA decay | 60 |

| YTH m6A-binding protein 3 (YTHDF3) | Direct m6A reader | Unknown | 60 |

m6A, N6-methyladenosine; YTH, YT521-B homology.

m6A modulates mRNA metabolism

N6-adenosine methylation affects almost every stage of mRNA metabolism, from processing in the nucleus to translation and decay in the cytoplasm. Two distinct modes of function have been identified for m6A readers: indirect reading and direct reading. Indirect reading involves m6A alterations to RNA secondary structures, thereby rendering the RNA accessible to a unique set of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). Direct reading involves m6A selectively binding to RBPs with diverse cellular functions (TABLE 1).

m6A alters RNA folding and structure

The methyl group at the N6 position of m6A does not change Watson–Crick A•U base pairing but weakens duplex RNA by up to 1.4 kcal per mol68. In unpaired positions, m6A stacks better than an unmodified base, thereby stabilizing surrounding RNA structures69,70 or promoting the folding of adjacent RNA sequences71. Transcriptome-wide RNA structure mapping has confirmed that methylated RNA regions prefer single-stranded structures to double-stranded structures70,72–74. In addition, a recent report revealed that m6A within coding regions could induce steric constraints that destabilize pairing between codons and tRNA anticodons, thus affecting translation dynamics75.

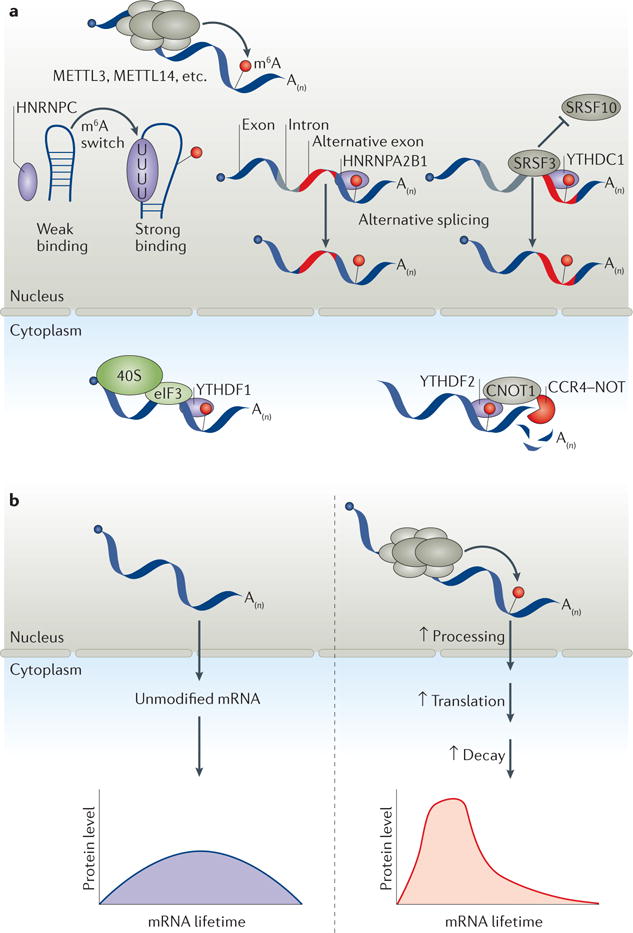

Owing to these thermodynamic effects, m6A-triggered structural remodelling may change the accessibility of RBP interaction motifs to RNA, a phenomenon termed the m6A switch67. The methylation of an RRACH motif in a stem structure in several genes, for example, in metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) and CDP-diacylglycerol synthase 2 (CDS2), causes its destabilization and the opening of the duplex. A single-stranded U-tract is then exposed, which can be recognized by HNRNPC to regulate the splicing of these transcripts67,76 (FIG. 2a). m6A switches may be widespread across the transcriptome and therefore may have profound roles in mediating interactions between RNA and RBPs67,76.

Figure 2. m6A-dependent mRNA processing promotes translation and decay, and affects splicing.

a| After being deposited by the methyltransferase core catalytic components methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and METTL14, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is recognized by various reader proteins. In the nucleus, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (HNRNPC) functions as an indirect m6A reader by binding unstructured m6A switch regions and regulating splicing, whereas YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing 1 (YTHDC1) regulates alternative splicing by binding m6A directly and recruiting the splicing factors serine and arginine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) while blocking binding by SRSF10. HNRNPA2B1 also mediates alternative splicing in a manner similar to YTHDC1. In the cytoplasm, YTHDF1 mediates translation initiation of m6A-containing transcripts by binding directly to m6A and recruiting eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3), thereby facilitating the loading of the eukaryotic small ribosomal subunit (40S). YTHDF2 promotes mRNA decay by binding to CCR4–NOT transcription complex subunit 1 (CNOT1), thereby facilitating the recruitment of the CCR4–NOT complex and inducing accelerated deadenylation. b | Methylated transcripts may be sorted by reader proteins into a fast track (right) for processing, translation and decay. This fast-tracking effectively groups transcripts with otherwise markedly different properties to ensure their timely and coordinated translation and degradation, possibly generating a sharp ‘pulse’ of gene expression to satisfy a need for translational bursts and subsequent clearance of these transcripts.

m6A affects mRNA maturation

Processing of pre-mRNA to mature mRNA consists of three main steps: 5′ capping, 3′ polyadenylation and splicing. m6A was initially proposed to function as a splicing regulator, as early studies found it to be more abundant in pre-mRNA than in mature mRNA77, with many m6A sites concentrated in introns78,79. mRNAs that undergo alternative splicing also have more METTL3-binding sites and more N6-adenosine methylation sites39,49. Writers and erasers of m6A localize predominantly in nuclear speckles39,43,44,63, which are sites of mRNA splicing and storage. PAR-CLIP (photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation) data showed that most METTL3-binding sites reside in introns39, and the depletion of Mettl3 in mouse embryonic stem cells (mouse ES cells) generally favours exon skipping and intron retention80. These results indicate that the recruitment of METTL3 to pre-mRNA is a co-transcriptional event, with methylation potentially preceding and influencing splicing. FTO also modulates alternative splicing by removing m6A around splice sites and by preventing binding of serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor 2 (SRSF2)81. m6A readers also affect splicing. YTHDC1 recruits SRSF3 while blocking binding by SRSF10, leading to exon inclusion63 (FIG. 2a). HNRNPA2B1 and HNRNPC are also active splicing regulators67,82,83. HNRNPA2B1 regulates alternative splicing events in a similar manner to METTL3 (REF. 66), as well as microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis from intronic sequences, which is a process closely coupled with splicing66,84 (Supplementary information S2 (box)).

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) is coupled to splicing of the last intron85 and associated with mRNA N6-adenosine methylation. Two-thirds of m6A sites in the last exon are found at the 3ʹ UTR, where APA sites reside56, and the knockdown of m6A writers can cause APA56. Recent studies of APA mRNA isoforms have revealed that isoforms with m6A tend to utilize proximal APA sites and have shorter 3′ UTRs compared to non-methylated isoforms86. Collectively, these results demonstrate that m6A methylation is intimately linked to early mRNA processing.

m6A enhances nuclear processing and export of mRNAs

mRNA nuclear export is a key process that connects transcription and processing in the nucleus to translation in the cytosol, and can selectively modulate gene expression87. N6-adenosine methylation was suggested to promote mRNA export: depletion of METTL3 inhibited mRNA export88, whereas depletion of ALKBH5 enhanced mRNA export to the cytoplasm44. Mechanistic details are yet to be reported, but it is conceivable that nuclear readers have an active role in this process. Facilitating mRNA export to the cytoplasm could be a major mechanism by which m6A regulates gene expression.

m6A promotes mRNA translation

Translation is promoted by N6-adenosine methylation through several mechanisms. YTHDF1 globally promotes translation of m6A-methylated mRNAs by binding m6A-modified mRNA and recruiting translation initiation factors, thereby significantly improving the efficiency of cap-dependent translation61. YTHDF1 not only couples methylated transcripts with ribosomes but also recruits the translation initiation factor complex eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) (FIG. 2a) to promote the rate-limiting step of translation. METTL3 was recently shown to function also as an m6A reader by enhancing eIF4E-dependent translation in a specific subset of mRNAs by recruiting eIF3 during translation initiation89. This effect was independent of its methyltransferase activity or the YTHDF1–eIF3 pathway89. Two recent studies have further indicated that the presence of m6A at the 5′ UTR improves cap-independent translation52,90, and eIF3 was proposed to interact with m6A and facilitate ribosome loading90. Collectively, these findings suggest several distinct mechanisms by which m6A promotes mRNA translation.

m6A marks mRNA for decay

Decay is the final step in mRNA metabolism, during which mRNA is destabilized and degraded. m6A has been linked to reduced mRNA stability, as knockdown of METTL3 and METTL14 in human and mouse cells has been shown to lead to increases in the expression of their respective target mRNAs37,38. Although most m6A sites appear to accelerate mRNA decay, the impact on the transcriptome, including both methylated and unmethylated transcripts, can be more complex. This reasoning is because many mRNAs encoding transcription repressors are target substrates of the methyltransferase complex; reduced methylation of these transcripts could cause transcription repression.

Mechanistic studies of the cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF2 (REFS 49,60) provided the first direct evidence of an m6A-dependent mRNA decay pathway60. Similar to YTHDF1, YTHDF2 is a two-domain protein: the carboxy-terminal YTH domain selectively binds methylated transcripts, whereas the amino-terminal functional domain delivers the YTHDF2-bound transcripts to cytoplasmic RNA decay machinery for dedicated degradation60. Knockdown of YTHDF2 prolonged the stability of its target mRNAs, indicating that it promotes mRNA decay of N6-adenosine methylation. YTHDF2 was shown to associate with CCR4–NOT transcription complex subunit 1 (CNOT1)60, which facilitates the recruitment of the CCR4–NOT complex and induces accelerated deadenylation of YTHDF2-bound mRNA91. The YTHDF2-dependent degradation of N6-adenosine-methylated mRNAs represents a crucial role for m6A, which is in accordance with increased gene expression observed with the knockdown of m6A writers37,38.

Additionally, the YTHDF2-bound m6A sites may also be recognized by other effectors of mRNA stability, such as ELAV-like RNA binding protein 1 (ELAV1; also known as HuR)38,92, miRNAs93 and the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family protein members TLR3 and TLR7 (REF. 94). Considering the proposed role of m6A in miRNA biogenesis (Supplementary information S2 (box)), these pathways could intersect to cooperatively control the stability of target mRNAs. The decay of methylated transcripts appears to be a major factor in promoting mouse ES cell differentiation and facilitating mouse embryogenesis80. In summary, m6A generally functions as a destabilizer of mRNAs and facilitates the degradation of methylated transcripts in various biological contexts.

m6A sorts transcripts into a fast track for mRNA metabolism

The life cycle of mRNAs is regulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory processes, including processing, export, translation and decay. Recent studies have revealed that m6A and its related factors influence each of these steps. As these processes are generally coupled, we propose that mediators of N6-adenosine methylation may work in concert to shape the methylation pattern and protein binding of specific transcripts, thereby affecting their metabolism. One example of such cooperation is the co-regulation of translation and decay by YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 of their shared targets61. Both the translation efficiency and the degradation of these mRNAs are reduced by double knockdown of YTHDF1 and YTHDF2. The combined function of the YTHDF1-dependent translation promotion and YTHDF2-dependent decay may result in a spike in protein production61 (FIG. 2b). This effect, along with other m6A-mediated effects such as accelerated export of certain methylated mRNA, suggests a critical function for m6A-based gene regulation: writers and erasers dictate the levels of target-specific m6A. In turn, readers decode these messages and may functionally sort methylated mRNAs into distinct functional groups. During cell differentiation and development, when the translation of groups of transcripts is accomplished within a short time span, methylation could sort these transcript groups into a fast track for processing, translation and decay. Methylation could be particularly beneficial in grouping and synchronizing the expression of hundreds to thousands of mRNAs that otherwise may possess markedly different properties with varied stabilities and translation efficiencies. Such a mechanism may also help in generating translation ‘pulses’ to satisfy the need for bursts of protein synthesis as well as rapid decay to regulate cell differentiation during early development (FIG. 2b).

m6A shapes cell function and identity

The molecular functions of m6A collectively translate into the control of complex cellular functions. Such controls may be required during the cellular transition between distinct states during differentiation and development, when cells rapidly replace their stage-specific transcriptomes to re-establish a new identity. m6A could be important in shaping the levels of mRNAs of various transcription factors and therefore may serve as barriers to or act as facilitators of these transitions.

m6A functions in circadian rhythm maintenance and cell cycle regulation

One of the earliest identified effects of m6A on cell function was discovered during a study of the mammalian circadian rhythm88. Maintenance of the circadian rhythm (clock) involves a negative feedback loop of gene expression, in which clock proteins downregulate the transcription of clock genes. However, only one-fifth of these rhythmic genes are driven by de novo transcription95, indicating that post-transcriptional regulation has prominent roles in circadian rhythm control. Transcripts of numerous clock genes and clock output genes are modified by N6-adenosine methylation88. METTL3 knockdown leads to reduced N6-adenosine methylation of two key clock genes, period circadian clock 2 (PER2) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like (ARNTL), which prolongs their nuclear retention and thereby the circadian period88. These results demonstrate how changes in mRNA metabolism can have prolonged effects. Similarly, the cell cycle is an oscillating process that is functionally coupled with the circadian clock96. A notable shift in cell cycle duration following perturbation of m6A in mRNAs of transcription factors was also reported in mouse ES cells97. More detailed studies are needed to fully elucidate the mechanism of cell cycle regulation by m6A.

m6A functions in cell differentiation and reprogramming

Cell differentiation is an essential process during which a cell changes its identity and specialization. N6-adenosine methylation in mRNAs affects cell differentiation and the expression of numerous transcription factors. For instance, m6A affects the differentiation of pre-adipocytes during adipogenesis81,98. FTO controls m6A levels, which in turn affects SRSF2 binding, thereby affecting the alternative splicing of numerous key genes that are required for adipogenesis81,98. ALKBH5 affects cell differentiation in human breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs)99. Exposure of BCSCs to hypoxia induces m6A demethylation by ALKBH5 of the key pluripotency factor NANOG, which increases transcript stability and promotes BCSC proliferation.

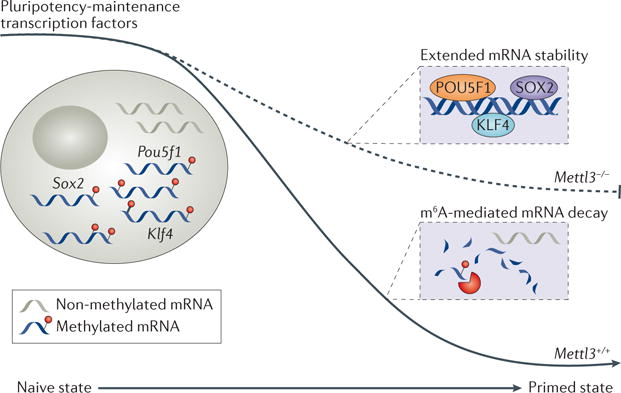

In-depth mechanistic studies carried out in mouse ES cells have demonstrated that proper differentiation requires m6A. Decreased m6A levels and reduced self-renewal of mouse ES cells were observed upon partial short hairpin RNA-mediated knockdown of Mettl3 and Mettl14 (REF. 38). By contrast, a CRISPR–Cas9 knockout of Mettl3 resulted in improved self-renewal and impaired differentiation69. Using homologous recombination to completely inactivate Mettl3, a subsequent study confirmed the crucial role of METTL3 in stem cell differentiation and detailed how m6A may drive mouse ES cells away from the pluripotent state80. Mettl3 knockout is embryonic lethal, which is probably due to the retention of pervasive NANOG expression and severely limited embryonic priming. Specifically, m6A supports the timely transition from naive pluripotency to lineage commitment, potentially by facilitating the decay of naive pluripotency-promoting transcripts80. Cell reprogramming, the reverse process of cell differentiation, was shown to be affected by METTL3 in the same study, in which the reprogramming of differentiated mouse epiblast stem cells to mouse ES cells was blocked by inactivation of Mettl3 early during development but facilitated by inactivation late during development. Zinc finger protein 217 (ZFP217) is partially responsible for stabilizing key pluripotency and reprogramming transcripts by inhibiting their METTL3-mediated methylation, thus promoting self-renewal of mouse ES cell and reprogramming of somatic cells97.

m6A facilitates cell state transitions

The collective influence of m6A affects cell function most probably through the regulation of a subset of key transcription factors that determine cell fate. N6-adenosine methylation has been found on transcripts of numerous transcription factors that control cellular state and lineage commitment. Such transcription factors include the core pluripotency factors NANOG and the so-called Yamanaka reprogramming factors100 — the transcription factors POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 (POU5F1; also known as OCT4), SOX2, MYC and Krueppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) — that are necessary and sufficient to induce the formation of pluripotent stem cells69,97,99. The cellular composition of expressed transcription factors can either maintain cell state or promote cell differentiation. By facilitating the downregulation of transcripts encoding such dominant transcription factors, the barrier to cell-state transition could be tuned by changes in mRNA m6A levels (FIG. 3). Thus, in cells in which N6-adenosine-methylated transcripts maintain pluripotency (or any other cell state), reducing m6A levels may increase the barrier for differentiation by reducing the decay and prolonging the lifetime of these mRNAs. Conversely, in cells in which methylated transcripts drive a transition to a new cell state, reducing m6A levels could promote cell differentiation, whereas increased overall methylation could induce stemness and suppress cell differentiation. Experimental results so far suggest that m6A is crucial for shaping cell states during cell differentiation and development. The effects of m6A on mammalian development and human diseases such as cancer progression and metastasis are only beginning to emerge (BOX 1).

Figure 3. m6A affects mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation.

The N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) methyltransferase METTL3 (methyltransferase-like 3) is required for the transition of mouse embryonic stem cells (mouse ES cells) from a naive to the more differentiated primed state. During this process, the key pluripotency factor transcripts POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1(Pou5f1), Krueppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) and Sox2 must be cleared. In mouse ES cells lacking Mettl3, this clearance is defective because non-methylated mRNAs are less subjected to decay, which prevents the establishment of a differentiated transcriptome required to achieve a primed mouse ES cell state.

m6A functions in stress responses

Owing to rapid response kinetics and potential for both short-term and long-term effects, the regulation of mRNA metabolism is particularly crucial under stress conditions such as extreme temperatures, deprivation of oxygen or nutrients, and exposure to toxins. Early work suggested that N6-adenosine methylation on key transcripts in budding yeast is crucial for meiosis initiation in response to nitrogen starvation74. The m6A reader protein YTHDF1 was shown to localize to stress granules along with stalled translation machinery following arsenite-induced oxidative stress, and to facilitate a post-stress recovery response by promoting translation restoration61. During the heat shock response, YTHDF2 localizes to the nucleus and promotes 5′ UTR methylation by inhibiting FTO binding. This process enables selective cap-independent translation under stress conditions despite global translation suppression52. In addition, hypoxic stress induces hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent ALKBH5 expression and subsequent removal of m6A from the transcripts encoding the pluripotency factor NANOG, leading to increased NANOG expression and BCSC proliferation99. These results indicate that the proposed m6A-mediated fast-tracking mechanism of mRNA processing could also be employed in response to various cellular stresses in addition to affecting cell state transitions.

Other mRNA modifications

Several distinct chemical modifications are abundant in many RNA species, in particular on tRNAs, for which modifications are known to affect translation101–104. Apart from the 5′ cap modifications and the 3′ poly(A) tail found on eukaryotic mRNA, coding transcripts feature several chemical modifications with emerging regulatory functions. The availability of high-throughput sequencing techniques, combined with highly sensitive mass spectrometry technology, has aided the discovery of new modifications that have potential regulatory functions.

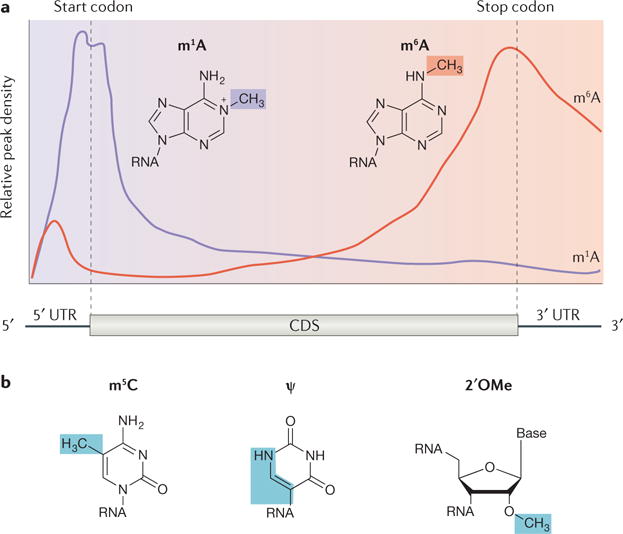

N1-methyladenosine

First discovered in total RNA samples decades ago105, N1-methyladenosine (m1A) is a modification that was previously known to regulate the structure and stability of tRNA and rRNA106,107. Recent studies have also revealed the presence of m1A in eukaryo tic mRNAs108,109. The positive charge associated with this modification could potentially augment its biological impact by strengthening RNA–protein interactions or by altering RNA secondary structures. A recent study showed that m1A disrupts RNA base-pairing and induces local RNA duplex melting110. In addition to the structural modifications induced by m1A, two recent reports have described the transcriptome-wide distributions of m1A in human and mouse cells and tissues108,109. Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing was used to map more than 7,000 m1A locations in coding and long non-coding RNAs, and a combination of immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing with the Dimroth rearrangement of m1A to m6A was used to obtain high-resolution information of RNA N1-adenosine methylation108. The other study exploited the inherent ability of m1A to stall reverse transcription and identified more than 900 m1A sites in 600 genes109. Both studies suggested that each modified transcript contains on average one m1A, in contrast to m6A-containing transcripts, which tend to be methylated in multiple sites. The distribution of m1A in mRNAs is unique in its proximity to translation starting sites and the first splice site — a pattern distinct from the 3′ UTR enrichment of m6A (FIG. 4a). The function of m1A remains unclear, although it probably promotes translation108. Future work to identify key mediators of N1-adenosine methylation as well as its biological functions will be essential to understanding this new component of the epitranscriptome.

Figure 4. m6A and other mRNA post-transcriptional modifications.

a| Qualitative distribution profiles of N1-methyladenosine (m1A; purple) and N6-methyladenosine (m6A; red) in mRNA. m1A is found primarily near translation start codons and first splice sites108, whereas m6A is primarily found in long exons and within 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs)49. b | In addition to m6A and m1A, other chemical modifications found on eukaryotic mRNA with emerging regulatory functions include 5-methylcytosine (m5C), pseudouridine (ψ) and 2′-O-methylation (2′OMe). CDS, coding DNA sequence.

5-Methylcytosine

m5C (FIG. 4b) has long been studied as an epigenetic modification in DNA. m5C is known to exist in eukaryotic mRNA at levels well below that of m6A levels8, but, until recently, its distribution and function in mRNAs have not been characterized. Adopting the bisulfite treatment that was originally developed for m5C detection in DNA, several m5C sites in tRNA and rRNA have been characterized111–113, followed by the report of high-resolution maps of m5C in mRNAs114. Following the report in yeast that tRNA methyltransferase 4 (Trm4) is a tRNA 5-cytosine methyltransferase115, tRNA aspartic acid methyltransferase 1 (also known as Dnmt2) was reported to be a tRNA m5C writer in several eukaryotic species and shown to have protective functions against stress-induced tRNA cleavage111,116–118. Another tRNA methyltransferase, NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 2 (NSUN2, a homologue of yeast Trm4)119, was reported to also methylate 5-cytosine in mRNAs and in various non-coding RNAs114,120–122. Nevertheless, biological functions of m5C in eukaryotic mRNAs remain largely elusive, although the oxidative derivatives of m5C, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-formylcytosine, have been detected in RNA from Drosophila spp. to mammalian cells and brain tissues123–126, suggesting that it is a dynamic modification with potential regulatory roles.

Pseudouridine

The most abundant modification in cellular RNA is pseudouridine (ψ)127 (FIG. 4b). Generated by the isomerization of uridine, this modified base is relatively highly abundant in rRNA and tRNA. Pseudouridine mapping has been recently accomplished at single-base resolution, identifying hundreds of sites in yeast mRNAs128,129 as well as 96 sites in mammalian mRNAs129. A chemical biology approach was used to effectively enrich for pseudouridine-containing transcripts, revealing thousands of modified sites in mammalian mRNAs130. The ability of pseudouridine to alter base-pairing interactions allows it to affect not only RNA structures but also mRNA coding131, underscoring its potential as a regulatory element. Known pseudouridine synthase enzymes have been shown to mediate isomerization in mRNA as well as tRNA, suggesting that they may serve as mRNA writer proteins132.

2′-O-methylnucleosides

2′-O-methylation (2′OMe) is a common RNA modification that resides on the 2′ hydroxyl ribose moiety of all four ribonucleosides (FIG. 4b). 2′OMe has been found in all major classes of eukaryotic RNA133–135, and its existence in human mRNA was reported at the same time that m6A was discovered2. 2′OMe can inhibit A to I RNA editing in vitro136. Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) are known to guide 2′OMe on eukaryotic rRNA137, and recent studies have suggested that certain snoRNAs may also target other RNA species such as mRNA137,138. Several methods exist for 2′OMe detection139, including PCR-based quantitative methods140,141 and a high-throughput sequencing strategy (RiboMeth-Seq)142, which have the potential to be applied to study mRNA modifications. However, the precise sites of 2′OMe in eukaryotic mRNA or its function are currently unclear.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

The main features of m6A on mRNA are its prevalence, unique distribution patterns along transcripts and dynamic nature. The biologically relevant reversibility of m6A distinguishes it from irreversible RNA cis elements. Additionally, although more than 7,000 human genes contain m6A sites (making m6A the most widespread mRNA functional element), the majority of potential m6A sites (RRACH motifs) are unmethylated, and most methylated sites are only partially (6–80%) modified67. Such sub-stoichiometry suggests that a large dynamic margin exists for m6A-based regulation across the transcriptome and that N6-adenosine methylation provides greater capacity (compared to binary regulatory elements) for fine-tuning regulatory mechanisms. The notion of incompleteness is further supported by the highly uneven distribution of m6A along transcripts and the tissue-specific m6A patterns observed in many organisms. These features indicate that for each m6A site on a given transcript the ratio between methylated and unmethylated forms can be dynamic, potentially allowing for a rapidly tuned response to various internal and external stimuli.

The effects of incomplete N6-adenosine methylation may be accomplished by numerous mechanisms, and methylation patterns of individual transcripts may function as molecular markers decoded by relevant readers. mRNA transcripts could therefore be sorted into different groups with differential downstream metabolism. This hypothesis is supported by the recent report that methylated transcript isoforms have shorter 3′ UTRs and lower stability than non-methylated transcripts86. We propose that the ‘fast-track’ group of methylated transcripts enjoys accelerated nuclear export, translation and degradation, which are facilitated by the concerted binding of m6A readers. This process means that methylated mRNAs, in particular those encoding transcription factors and regulatory proteins, can be synchronized in response to differentiation, development and other stimuli. The stimuli-triggered changes of writer and/or eraser activities may themselves be induced by transcription factors (for example, HIF-dependent ALKBH5 activity99 and ZFP217-dependent METTL3 activity97) or miRNAs (such as miRNA-dependent METTL3 activity143), suggesting a complex interplay between m6A and other regulatory pathways.

We propose two hallmarks to mRNA N6-adenosine methylation: that it serves as a marker to group and synchronize cohorts of transcripts for fast-tracking mRNA processing and metabolism; and that it considerably affects cell-state transition during cell differentiation. How selectivity and transcript grouping are achieved and how writers, erasers and readers are coordinated in response to different signalling pathways are unknown. We propose that the same stimuli and regulatory processes that tune transcription and translation may also affect these writers, erasers and readers through different forms of post-translational modifications. For example, when certain transcription factors are activated they may directly affect the accessibility and recruitment of writers. The same signalling pathway may coordinately activate or inactivate erasers and readers through direct recruitment or post-translational modifications (FIG. 5). This process could be a fundamental mechanism that mammalian cells exploit to coordinate gene expression during development. Defects in such processes may cause or contribute to human diseases. For example, various human cancers are known to have perturbations in the expression of m6A writers, erasers and readers (BOX 1). Thus, the epitranscriptome may contribute to tumorigenesis.

Figure 5. m6A synchronizes mRNA processing in response to various internal and external stimuli.

The activities of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) writers, erasers and readers may be regulated by the same signalling pathways and stimuli that tune transcription and translation, potentially through various post-translational modifications (not shown) on writers, erasers and readers. This process could constitute an additional mechanism to post-transcriptionally coordinate the expression of large groups of genes in response to internal and external stimuli, which may affect many physiological processes that require rapid responses involving multiple genes. ALKBH5, alkB homologue 5; CCR4–NOT, carbon catabolite repression 4–negative on TATA-less; eIF3, eukaryotic initiation factor 3; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; METTL, methyltransferase-like; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; WTAP, Wilms tumour 1-associated protein; YTHDF2, YT521-B homology domain-containing family protein 2.

Finally, m6A is but one of many post-transcriptional modifications in mRNA with regulatory roles that have been discovered or re-discovered in recent years. In addition to m6A, m1A, m5C, pseudouridine and 2′OMe, we suggest that additional regulatory chemical modifications may be discovered in mRNA. Each of these modifications may have a dedicated set of writers, erasers and readers, although some of them might be shared. The potential to decorate distinct parts of the pre-mRNA (5ʹ UTR, coding sequence, 3′ UTR, splice sites) could be used to modify different groups of transcripts in response to various stimuli. These mRNA chemical modifications could be regulated individually or combinatorially to affect the fate of individual mRNA species. More quantitative technologies will need to be developed to precisely map locations of these mRNA chemical modifications. Future work will also need to test and confirm the hallmarks of mRNA N6-adenosine methylation we have proposed above and to explore the effects of various mRNA modifications in biological processes such as cell differentiation and development. Further understanding is also needed in how transcript selectivity and site selectivity are achieved, how these mRNA chemical modification processes and their connections with different signalling pathways are regulated, the interplay and potential synergy between modification regulators and other cellular components, and their roles in human physiology.

Supplementary Material

Box 1. m6A-related phenotypes in various organisms.

In this Box, we summarize the reported phenotypic effects associated with N6-methyladenosine (m6A) and its regulatory factors in multicellular eukaryotes.

Plants

m6A was first found in monocot plants9–11 and subsequently in Arabidopsis thaliana, in which the writer protein MT-A70-like protein (homologue of the mammalian methyltransferase-like 3 (METLL3)) is required for embryogenesis12. Depletion of m6A during development affects normal growth patterns and apical dominance144. In A. thaliana, m6A is enriched in 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs)144 near stop codons and, uniquely, around start codons51. Genes with these unique m6A sites are enriched in plant-specific pathways involving chloroplast components51. m6A deposition is also positively correlated with the abundance of a large fraction of A. thaliana transcripts, suggesting that it has regulatory roles in plant gene expression51. Another study found that m6A patterns differ between plant organs, suggesting that m6A affects organogenesis and has cell-type specific functions145. Numerous homologues of mammalian m6A demethylases and the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain reader proteins exist in plant genomes. At least one A. thaliana alkB homologue (ALKBH) protein can catalyse m6A demethylation, which regulates floral transition and vegetative growth (G. Jia, personal communication, 2016).

Insects

Drosophila melanogaster was among the first organisms in which internal mRNA m6A was detected146. Inducer of meiosis 4 (homologue of mammalian METTL3) affects Notch signalling during egg chamber development147, and another potential component of the m6A writer complex, female lethal d (homologue of the mammalian Wilms tumour 1 associated protein (WTAP)), affects sexual determination via splicing regulation of two key genes148,149.

Fish

In zebrafish, the knockdown of mettl3 or wtap leads to several developmental defects, whereas a combined knockdown leads to increased apoptosis39. As zebrafish development requires rapid mRNA clearance during the maternal-to-zygotic transition150, an m6A-dependent mRNA degradation mechanism was proposed and shown to be crucial for zebrafish embryogenesis based on the function of Ythdf2 (B.S.Z. and C.H., unpublished observations).

Mouse

In mice, in addition to the regulation of embryonic development by METTL3 discussed in the main text, Alkbh5 knockout mice suffer from impaired spermatogenesis and male infertility44, whereas fat mass and obesity-associated protein (Fto)-deficient mice exhibit reduced body mass and early mortality45,151.

Human

m6A is linked to numerous human diseases. Several cancer types have been linked to m6A, although many of these connections are indirect152–163. More direct evidence emerged from the depletion of METTL3, which caused apoptosis and reduced invasiveness of cancer cells14,89, and from the activation of ALKBH5 by hypoxia, which caused cancer stem cell enrichment99. m6A has also been implicated in the regulation of metabolism and obesity: FTO was suggested to influence pre-adipocyte differentiation81,98,164, and SNPs in FTO associate with body mass index in human populations and the occurrence of obesity and diabetes165–169, despite a recent work arguing that the functional target of these obesity-associated SNPs is not FTO170. The connection between m6A and neuronal disorders has also been documented. For instance, dopamine signalling is dependent on FTO and on N6-adenosine methylation of key signalling transcripts46, and mutations in the prion-like domain of the reader protein heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1) are known to cause neurodegeneration through dysregulated protein polymerization171. FTO and ALKBH5 have been associated with the developments of depressive disorders172–175, and addiction, epilepsy, attention deficit disorder and other neurological disorders have also been associated with m6A regulators176–178. Reproductive disorders, viral infection, inflammation are also among the diseases influenced by m6A158,179–183. Viral RNAs carry internal m6A (Supplementary information S1 (box)), which is deposited by host enzymes and could be utilized by viruses to enhance their survival in mammalian host cells183.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited owing to space limitations. This research was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (HG008688 and GM071440 to C.H.). C.H. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). B.S.Z. is an HHMI International Student Research Fellow. I.A.R. is supported by a National Research Service Award F30GM117646 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Chicago is funded by the National Science Foundation (CHE-1048528).

Glossary

- S-Adenosyl methionine

A biochemical cofactor and methyl donor for mRNA N6-methyladenosine methylation and other methyl group transfer processes

- Epitranscriptome

The biochemical features of the transcriptome that are not genetically encoded in the ribonucleotide sequence

- m6A switch

mRNA sequence that adopts a secondary structure in dependence on N6-adenosine methylation

- Alternative polyadenylation

(APA). The alternative use of different polyadenylation sites at 3′ ends of transcripts

- CCR4–NOT complex

The complex multi-subunit carbon catabolite repression 4 (CCR4)–negative on TATA-less (NOT) is one of the major deadenylases in eukaryotic cells

- Clock output genes

A set of genes that are regulated transcriptionally by clock genes usually they control metabolic processes.

- Embryonic priming

The molecular transition of mouse embryonic stem cells from a naive cell state to a more differentiated or primed cell state, resembling transitions that occur during embryonic development in vivo

- Dimroth rearrangement

A rearrangement of 1,2,3-triazoles in which the endocyclic and exocyclic nitrogen atoms change place (here, allowing conversion of N6-methyladenosine to N1-methyladenosine in basic conditions)

- Bisulfite treatment

Treatment of nucleic acid with bisulfite to convert cytosine to uracil, leaving 5-methylcytosine unchanged and distinguishable by reverse transcription or PCR

Footnotes

References

- 1.Machnicka MA, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways — 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D262–D267. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3971–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry RP, Kelley DE. Existence of methylated messenger RNA in mouse L cells. Cell. 1974;1:37–42. References 2 and 3 present the first reports of the existence of m6A in the internal region of mRNA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavi S, Shatkin AJ. Methylated simian virus 40-specific RNA from nuclei and cytoplasm of infected BSC-1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2012–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei CM, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′-terminus of vaccinia virus messenger-RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:318–322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuichi Y, et al. Methylated, blocked 5′ termini in HeLa cell mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1904–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams JM, Cory S. Modified nucleosides and bizarre 5′-termini in mouse myeloma mRNA. Nature. 1975;255:28–33. doi: 10.1038/255028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubin DT, Taylor RH. The methylation state of poly A-containing messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975;2:1653–1668. doi: 10.1093/nar/2.10.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols JL. N 6-methyladenosine in maize poly(A)-containing RNA. Plant Sci Lett. 1979;15:357–361. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy TD, Lane BG. Wheat embryo ribonucleates. XIII Methyl-substituted nucleoside constituents and 5′-terminal dinucleotide sequences in bulk poly(AR)-rich RNA from imbibing wheat embryos. Can J Biochem. 1979;57:927–931. doi: 10.1139/o79-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haugland RA, Cline MG. Post-transcriptional modifications of oat coleoptile ribonucleic acids. 5′-Terminal capping and methylation of internal nucleosides in poly(A)-rich RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1980;104:271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong SL, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1278–1288. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz S, Horowitz A, Nilsen TW, Munns TW, Rottman FM. Mapping of N6-methyladenosine residues in bovine prolactin mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5667–5671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bokar JA. In: Fine-Tuning of RNA Functions by Modification and Editing. Grosjean H, editor. Springer Berlin; Heidelberg: 2005. pp. 141–177. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Characterization of Novikoff hepatoma messenger-RNA methylation. Fed Proc. 1975;34:628. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry RP, Kelley DE, Friderici K, Rottman F. Methylated constituents of L cell messenger-RNA — evidence for an unusual cluster at 5′ terminus. Cell. 1975;4:387–394. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry RP, Kelley DE, Friderici KH, Rottman FM. Methylated constituents of heterogeneous nuclear-RNA — presence in blocked 5′ terminal structures. Cell. 1975;6:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell. 1975;4:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimock K, Stoltzfus CM. Sequence specificity of internal methylation in B77 avian sarcoma virus RNA subunits. Biochemistry. 1977;16:471–478. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beemon K, Keith J. Localization of N6-methyladenosine in the Rous sarcoma virus genome. J Mol Biol. 1977;113:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ, Stavnezer E, Bishop JM. Blocked, methylated 5′-terminal sequence in avian sarcoma virus RNA. Nature. 1975;257:618–620. doi: 10.1038/257618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sommer S, et al. The methylation of adenovirus-specific nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3:749–765. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canaani D, Kahana C, Lavi S, Groner Y. Identification and mapping of N6-methyladenosine containing sequences in simian virus 40 RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:2879–2899. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.8.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowalak JA, Dalluge JJ, McCloskey JA, Stetter KO. The role of posttranscriptional modification in stabilization of transfer RNA from hyperthermophiles. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7869–7876. doi: 10.1021/bi00191a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grosjean H, Gupta R, Maxwell E, Archaea S. In: New Models for Prokaryotic Biology. Blum P, editor. Norfolk Caister: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng X, et al. Widespread occurrence of N6-methyladenosine in bacterial mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6557–6567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krug RM, Morgan MA, Shatkin AJ. Influenza viral mRNA contains internal N6-methyladenosine and 5′-terminal 7-methylguanosine in cap structures. J Virol. 1976;20:45–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.20.1.45-53.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rottman F, Shatkin AJ, Perry RP. Sequences containing methylated nucleotides at the 5′ termini of messenger RNAs: possible implications for processing. Cell. 1974;3:197–199. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodi Z, Button JD, Grierson D, Fray RG. Yeast targets for mRNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5327–5335. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayan P, Rottman FM. In: Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. Nord FF, editor. Vol. 65. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 255–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane SE, Beemon K. Precise localization of m6A in Rous-sarcoma virus-RNA reveals clustering of methylation sites — implications for RNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2298–2306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.9.2298. The first work reporting the consensus sequence of N6-adenosine methylation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayan P, Rottman FM. An in vitro system for accurate methylation of internal adenosine residues in messenger RNA. Science. 1988;242:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3187541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csepany T, Lin A, Baldick CJ, Jr, Beemon K. Sequence specificity of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20117–20122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narayan P, Ludwiczak RL, Goodwin EC, Rottman FM. Context effects on N6-adenosine methylation sites in prolactin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:419–426. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bokar JA, Rath-Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17697–17704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233–1247. Pinpoints METTL3 as a key catalytic component of the m6A methyltransferase complex. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JZ, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. Characterizes the m6A methyltransferase complex comprising METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP as key components. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ping XL, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz S, et al. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5′ sites. Cell Rep. 2014;8:284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwala SD, Blitzblau HG, Hochwagen A, Fink GR. RNA methylation by the MIS complex regulates a cell fate decision in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He C. Grand challenge commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:863–865. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jia GF, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. Reports the discovery of the first m6A demethylase, FTO, thereby demonstrating m6A as the first reversible RNA modification and suggesting it has biological functions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng GQ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. Reports the second mammalian m6A demethylase ALKBH5 and its involvement in mouse spermatogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerken T, et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science. 2007;318:1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1151710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hess ME, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1042–1048. doi: 10.1038/nn.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung MK, Gulati P, O’Rahilly S, Yeo GSH. FTO expression is regulated by availability of essential amino acids. Int J Obes. 2013;37:744–747. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vujovic P, et al. Fasting induced cytoplasmic Fto expression in some neurons of rat hypothalamus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. The first report of transcriptome-wide m6A distribution, identifying enrichment in long exons, near stop codons and at 3′ UTRs, and suggesting several RBPs as m6A readers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer KD, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. Together with reference 49, reports pervasive m6A sites in mammalian mRNA and non-coding RNA as a feature of the mammalian transcriptome with a unique distribution pattern within mRNAs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo GZ, et al. Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5630. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou J, et al. Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu N, et al. Probing N6-methyladenosine RNA modification status at single nucleotide resolution in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA. 2013;19:1848–1856. doi: 10.1261/rna.041178.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen K, et al. High-resolution N6-methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:1587–1590. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linder B, et al. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods. 2015;12:767–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ke SD, et al. A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3′ UTR regulation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:2037–2053. doi: 10.1101/gad.269415.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sergiev PV, et al. N6-methylated adenosine in RNA: from bacteria to humans. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:2134–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. Reports YTHDF2 as the first m6A reader and reveals that it promotes the degradation of target mRNAs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. Characterizes the second m6A reader protein, YTHDF1 and reveals that it promotes translation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu C, et al. Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:927–929. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao W, et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo S, Tong L. Molecular basis for the recognition of methylated adenines in RNA by the eukaryotic YTH domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13834–13839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412742111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu T, et al. Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2014;24:1493–1496. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alarcon CR, et al. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A -dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 2015;162:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu N, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA–protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. Reports m6A-dependent modulation of RNA secondary structures (m6A switch) and an indirect m6A reader, HNRNPC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kierzek E, Kierzek R. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4472–4480. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Batista PJ, et al. m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roost C, et al. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2107–2115. doi: 10.1021/ja513080v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El Yacoubi B, Bailly M, de Crecy-Lagard V. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:69–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spitale RC, et al. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature. 2015;519:486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wan Y, et al. Landscape and variation of RNA secondary structure across the human transcriptome. Nature. 2014;505:706–709. doi: 10.1038/nature12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwartz S, et al. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155:1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047. Reveals transcriptome-wide m6A dynamics during meiosis in yeast. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi J, et al. N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:110–115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou KI, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification in a long noncoding RNA hairpin predisposes its conformation to protein binding. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:822–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salditt-Georgieff M, et al. Methyl labeling of HeLa cell hnRNA: a comparison with mRNA. Cell. 1976;7:227–237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carroll SM, Narayan P, Rottman FM. N6-methyladenosine residues in an intron-specific region of prolactin pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4456–4465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stoltzfus CM, Dane RW. Accumulation of spliced avian retrovirus mRNA is inhibited in S-adenosylmethionine-depleted chicken embryo fibroblasts. J Virol. 1982;42:918–931. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.3.918-931.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geula S, et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. Reference 38, 69 and 80 report the effects of m6A in embryonic cell differentiation, with reference 80 providing a thorough demonstration of m6A functions under different stages of differentiation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao X, et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014;24:1403–1419. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Konig J, et al. iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alarcon CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Movassat M, Crabb T, Busch A, Shi Y, Hertel K. Coupling between alternative polyadenylation and alternative splicing is limited to terminal introns. RNA Biol. 2016;13:646–655. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1191727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Molinie B, et al. m6A -LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m6A epitranscriptome. Nat Methods. 2016;13:692–698. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wickramasinghe VO, Laskey RA. Control of mammalian gene expression by selective mRNA export. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:431–442. doi: 10.1038/nrm4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fustin JM, et al. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;155:793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.026. Reports that m6A affects mRNA nuclear processing and regulates the circadian clock. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021. Provides molecular evidence of direct regulatory roles of m6A in cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meyer KD, et al. 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Du H, et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4–NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grimson A, et al. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koike N, et al. Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals. Science. 2012;338:349–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Feillet C, van der Horst GTJ, Levi F, Rand DA, Delaunay F. Coupling between the circadian clock and cell cycle oscillators: implication for healthy cells and malignant growth. Front Neurol. 2015;6:96. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aguilo F, et al. Coordination of m6A mRNA methylation and gene transcription by ZFP217 regulates pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:689–704. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Merkestein M, et al. FTO influences adipogenesis by regulating mitotic clonal expansion. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang C, et al. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m6A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2047–E2056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602883113. Demonstrates that the m6A demethylase ALKBH5 can be tuned by an intrinsic signalling pathway and provides molecular evidence of direct regulatory roles of m6A in cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Agris PF. The importance of being modified: an unrealized code to RNA structure and function. RNA. 2015;21:552–554. doi: 10.1261/rna.050575.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Phizicky EM, Hopper AK. tRNA processing, modification, and subcellular dynamics: past, present, and future. RNA. 2015;21:483–485. doi: 10.1261/rna.049932.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gu C, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. tRNA modifications regulate translation during cellular stress. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4287–4296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wei FY, et al. Cdk5rap1-mediated 2-methylthio modification of mitochondrial tRNAs governs protein translation and contributes to myopathy in mice and humans. Cell Metab. 2015;21:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dunn DB. The occurence of 1-methyladenine in ribonucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;46:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Helm M, Giegé R, Florentz CA. Watson–Crick base-pair-disrupting methyl group (m1A9) is sufficient for cloverleaf folding of human mitochondrial tRNALys. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13338–13346. doi: 10.1021/bi991061g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sharma S, Watzinger P, Kötter P, Entian KD. Identification of a novel methyltransferase, Bmt2, responsible for the N-1-methyl-adenosine base modification of 25S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5428–5443. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dominissini D, et al. The dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature. 2016;530:441–446. doi: 10.1038/nature16998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li X, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N 1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2040. References 108 and 109 describe high-throughput methods to map the transcriptome-wide distribution of m1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhou H, et al. m1A and m1G disrupt A-RNA structure through the intrinsic instability of Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:803–810. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schaefer M, et al. RNA methylation by Dnmt2 protects transfer RNAs against stress-induced cleavage. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1590–1595. doi: 10.1101/gad.586710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schaefer M, Pollex T, Hanna K, Lyko F. RNA cytosine methylation analysis by bisulfite sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schaefer M, Hagemann S, Hanna K, Lyko F. Azacytidine inhibits RNA methylation at DNMT2 target sites in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8127–8132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Squires JE, et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5023–5033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Motorin Y, Grosjean H. Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA. 1999;5:1105–1118. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goll MG, et al. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA methyltransferase homolog Dnmt2. Science. 2006;311:395–398. doi: 10.1126/science.1120976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rai K, et al. Dnmt2 functions in the cytoplasm to promote liver, brain, and retina development in zebrafish. Genes Dev. 2007;21:261–266. doi: 10.1101/gad.1472907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jurkowski TP, et al. Human DNMT2 methylates tRNAAsp molecules using a DNA methyltransferase-like catalytic mechanism. RNA. 2008;14:1663–1670. doi: 10.1261/rna.970408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brzezicha B, et al. Identification of human tRNA:m5C methyltransferase catalysing intron-dependent m5C formation in the first position of the anticodon of the pre-tRNALeu (CAA) Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6034–6043. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hussain S, Aleksic J, Blanco S, Dietmann S, Frye M. Characterizing 5-methylcytosine in the mammalian epitranscriptome. Genome Biol. 2013;14:215. doi: 10.1186/gb4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Khoddami V, Cairns BR. Identification of direct targets and modified bases of RNA cytosine methyltransferases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:458–464. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hussain S, et al. NSun2-mediated cytosine-5 methylation of vault noncoding RNA determines its processing into regulatory small RNAs. Cell Rep. 2013;4:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Delatte B, et al. RNA biochemistry. Transcriptome-wide distribution and function of RNA hydroxymethylcytosine. Science. 2016;351:282–285. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fu L, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11582–11585. doi: 10.1021/ja505305z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang HY, Xiong J, Qi BL, Feng YQ, Yuan BF. The existence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-formylcytosine in both DNA and RNA in mammals. Chem Commun (Camb) 2016;52:737–740. doi: 10.1039/c5cc07354e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Huber SM, et al. Formation and abundance of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. Chembiochem. 2015;16:752–755. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lane BG. In: Modification and Editing of RNA. Grosjean H, Benne R, editors. American Society of Microbiology; 1998. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schwartz S, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell. 2014;159:148–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Carlile TM, et al. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature. 2014;515:143–146. doi: 10.1038/nature13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Li XY, et al. Chemical pulldown reveals dynamic pseudouridylation of the mammalian transcriptome. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:592–597. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1836. References 128–130 describe high-throughput methods to map the transcriptome-wide distribution of pseudouridylation, with references 127 and 128 reporting single-base resolution and reference 129 high sensitivity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fernandez IS, et al. Unusual base pairing during the decoding of a stop codon by the ribosome. Nature. 2013;500:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Karijolich J, Yu YT. Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation. Nature. 2011;474:395–398. doi: 10.1038/nature10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Smith JD, Dunn DB. An additional sugar component of ribonucleic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;31:573–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hall RH. Method for isolation of 2′-O-methylribonucleosides and N1-methyladenosine from ribonucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;68:278–283. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cantara WA, et al. The RNA modification database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D195–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]