Abstract

Objective

Describe patterns of palliative care service consultation among a sample of ICU patients at high risk of dying.

Background

Patients receiving mechanical ventilation (MV) face threats to comfort, social connectedness and dignity due to pain, heavy sedation and physical restraint. Palliative care consultation services may mitigate poor outcomes.

Methods

From a dataset of 1440 ICU patients with ≥2 days of MV and ≥12 hours of sustained wakefulness, we identified those at high risk of dying and/or who died and assessed patterns of sub-specialty consultation.

Results

About half (773/1440[54%]) were at high risk of dying or died, 73(9.4%) of whom received palliative care consultation. On average, referral occurred after 62% of the ICU stay had elapsed. Primary reason for consult was clarification of goals of care (52/73[72.2%]).

Conclusions

Among MV ICU patients at high risk of dying, palliative care service consultation occurs late and infrequently, suggesting a role for earlier palliative care.

Introduction

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), especially those receiving mechanical ventilation (MV), face multiple threats to their comfort,1–6 their dignity,7, 8 and their ability to interact with and experience the presence of loved ones.9, 10 ICU patients who require MV >48 hours are at high risk of mortality,11 and the longer the duration of MV required, the greater the risk of in-hospital and one year mortality.12 Given that approximately 20% of US patients die having received ICU services, and the ICU remains the most common hospital setting wherein death occurs,13 the quality of dying is reflected in the extent to which patient comfort, dignity and social connectedness are impacted by ICU care practices.14, 15

Palliative care is a sub-specialty and an interdisciplinary approach to care that is focused on pain and symptom management; psychological and spiritual support; elicitation of patient values and preferences; communication about prognosis and treatment options; and alignment of treatment with goals of care for seriously-ill patients and their families.16, 17 The use of palliative care consultation services has been shown to improve patient outcomes related to quality of dying.18, 19 However, there is considerable variability in the types of services available20 as well as the timing, duration and mode of palliative care service delivery among ICU patients and across ICU units.

Provision of palliative care is recommended for all ICU patients, 21, 22 and is particularly applicable for patients who are at high risk of dying, as they and their families are highly likely to have unmet palliative care needs.23 Over the last 10 years there has been a steady increase in the establishment of sub-specialty palliative care programs and the availability of palliative care services to hospitalized patients.24 However, it is unclear if these services are reaching those patients and families with unmet palliative care needs. Most studies of palliative care consultation are limited to a single patient population, such as those with heart failure or metastatic disease.25 The current study provided the unique opportunity to explore patterns of palliative care consultation in a large sample of patients from six specialty ICUs, who were at high risk of dying and/or who died.

Methods

Overview

This expanded secondary analysis used a retrospective cohort design to study patients with ≥2 days of MV and ≥12 hours of sustained wakefulness admitted to six specialty ICUs within two tertiary-care sites from August, 2009 through July, 2011. The original sample and most outcome measures were drawn from a parent study testing the effectiveness of a unit-level multi-component communication intervention (see Parent Study, below). For the current study, we identified the sub-sample of patients who may have been dying (see Sample, below) and abstracted additional information regarding palliative care consultation from electronic medical records (EMR) of study subjects. The (name deleted for blinded review) IRB reviewed and approved the study.

Parent Study and Setting

The parent study collected outcome data on multiple measures of patient-centered care quality for a sample of 1440 randomly selected patients with ≥ 2 consecutive calendar days of MV and ≥12 hours of sustained wakefulness (during MV) from six ICUs (transplant, neuro-trauma, neurological, general trauma, cardiovascular and general medical) in two tertiary care hospitals belonging to a single health system located in the Mid-Atlantic region. Sustained wakefulness was defined by nursing documentation of being alert, arousable, anxious, or awake and/or one of the following: a best motor response score of 6 (obeys verbal commands) on the Glasgow Coma Scale; a score of 1–3 on the Modified Ramsay Scale, a score of ≥3 on the Riker Sedation Agitation Scale; or nursing documentation of communication with clinicians using head nods, gestures, or other non-vocal methods. The rationale for restricting the sample to ≥ 2 days of MV and ≥12 hours of sustained wakefulness while receiving MV during the ICU stay was to identify patients who could potentially benefit from the intervention, which provided bedside nurses with education, tools and hands-on troubleshooting related to communication with MV ICU patients. Details of the study design, methods and results of the parent study have been reported by (source deleted for blinded review).26

The parent study dataset included demographic and clinical characteristics as well as daily measures of pain, heavy sedation, and restraint use for the ICU stay, up to 28 days, and the incidence of ICU-acquired pressure ulcer over the ICU stay. Data on eligibility, demographic and clinical characteristics, and outcome measures were collected from the electronic health record by trained abstractors. A full description of the development and testing of the data collection tool and procedures was reported by (author name deleted for blinded review) and colleagues (in press).

Sample

Prior studies have used severity of illness scoring (APACHE II27) to identify ICU patients at high risk of dying. Similarly, we identified the patients at high risk dying using their APACHE III score,28 selecting a threshold score of ≥63. APACHE III scores range from 0 to 180, with higher values representing a higher risk of not surviving the ICU stay. Our threshold of ≥ 63 corresponds to a 24.7% predicted mortality, a similar value to that used by other studies of patients at high risk of dying. The rationale for including patients at high risk for dying who did not, in retrospect, actually die, was to address the clinical uncertainty associated with identifying patients who may be dying.29 We also included patients whose admission APACHE was <63 but who died during the ICU, as they also experienced ICU care (such as mechanical ventilation) that is potentially burdensome.

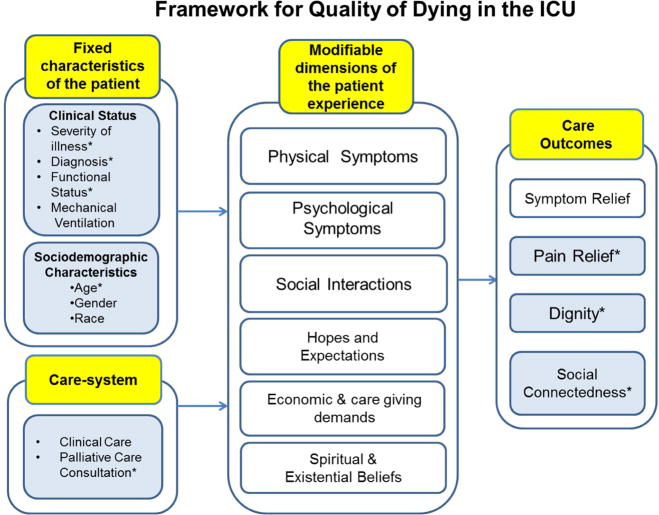

In a prior study of this cohort of patients at high risk of dying and/or who died (source deleted for blinded review), we showed a high prevalence of poor outcomes on measures of patient-centered care quality. The prior study was based on a theoretical framework adapted from Emanuel and Emanuel30 that considers the impact of patient characteristics and care system factors on modifiable dimensions of the patient experience (e.g., physical and psychological symptoms, social interactions) to produce care outcomes germane to those at high risk of dying (Figure 1). The care outcomes of interest to the study included pain relief, social connectedness, and dignity. Pain relief was measured by evaluating the frequency and intensity of pain as it is captured in the ongoing pain assessments documented in the EMR. Additionally, the occurrence of ICU acquired pressure ulcers, a source of ongoing pain and discomfort,5 was evaluated to capture an additional source for potential unrelieved pain. Social connectedness is dependent on a patient’s capacity to engage in social interactions, and derive comfort from the presence of others. Time spent under heavy sedation, a factor limiting social connectedness, reflects the degree to which social connectedness limited. Dignity has been defined as having self-esteem, respect, well-being, and pride.31–33 It is a self-defined concept and is dependent upon how one believes he or she is perceived (and treated) by others. Any care modality which decreases an individual’s sense of self-esteem and pride and conveys that he or she is not respected, serves to erode dignity. The psychological effects of being restrained are overwhelmingly negative, and the practice of restraint use has a profound effect on patients’ dignity.7, 8, 34 Time spent in physical restraint reveals the extent to which dignity was threatened.

Figure 1.

Adapted Theoretical Framework for Quality of Dying in the ICU

adapted from: Emanuel, E. J. & Emanuel, L. J. (1998) The promise of a good death. Lancet, 351, Sll21–Sll29

(Blue shading and an asterisk in the model denote those constructs measured in the study.)

Patients in this group of those at high risk of dying and/or who died experienced on average: 40% of days with some unrelieved pain; a mean highest daily pain score of 6.8 (1–10); 40.8% of days in restraint; and 35% of the ICU stay in a state of heavy sedation. In addition, 12.3 % developed a pressure ulcer, Stage II or greater, during their ICU stay. These outcomes are directly reflective of their quality of dying and demonstrate a need for palliative care services for this group.

Palliative Care Consultation Data Collection

Both hospital sites had a palliative care service available for consultation; however, the composition and the model of service delivery differed. Hospital A had a well-established, physician-led program consisting of palliative care physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), social workers, and a psychologist. Spiritual care was provided via the hospital pastoral care staff, who coordinated with the palliative care service team. Consultation was obtained via a formal medical order entered into the EMR. While any clinician could suggest a palliative care consultation, a medical order was necessary to obtain one. The palliative care service at Hospital B, during the study interval, was primarily nurse-led and consisted of nurses with specialized training in delivery of palliative care services, some of whom had advanced nursing degrees. The palliative care nurses coordinated with hospital social workers and pastoral care staff, but did not have dedicated social workers or psychologists on the team. Referrals to the palliative care service were made by physicians as well as other staff. Per hospital protocol, a formal medical order was required; however, the order was often entered into the EMR after the first consultation visit was made. The difference in the respective palliative care programs was due to the fact that Hospital B had recently merged with the health system; available services were historically different based on differing missions and leadership prior to the merger.

We abstracted data on palliative care consultation for our sample via EMR review. We determined if the patient had received a palliative care consultation using a review of medical orders and palliative care service consultation notes. Once we determined the patient had a palliative care consultation, we collected information regarding the referring physician; timing and duration of the consultation services within the ICU stay; and the palliative care team members who provided services (physician, nurse, social worker, and pastoral care). In terms of evaluating social work and pastoral care visits among palliative care service recipients at hospital B (where there were not dedicated palliative care team social workers or pastoral care providers), we counted visits by a social worker or pastoral care provider as palliative care service-related if the provider’s note included discussion with palliative care service nurse, attendance at family meetings convened by the palliative care service nurse, or discussion with the patient/family about end-of-life concerns or issues.

A trained student research assistant, along with the investigator (JBS) abstracted the data from the EMR. To evaluate the reliability of data collected, 10% of cases were co-abstracted for reliability of palliative care consult identification, and all cases with an identified palliative care service consultation were dually abstracted by the research assistant and the investigator. Analysis of inter-rater reliability (IRR) showed 98.6% agreement on palliative care consultation identification.

Analysis

We conducted data analysis using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (version 22.0, IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY), and set the level of significance at p <.05. We used descriptive and group comparative analyses to evaluate demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample and compare palliative care recipients and non-recipients. We used descriptive statistics to summarize characteristics of the palliative care consultation (reason(s) for consult, referring physician specialty/role, timing and duration of consultation, and palliative care provider roles).

Results

Prevalence and Patterns of Palliative Care Consultation

About half (773/1440 [52%]) of the patients from the parent sample were at high risk of dying and/or did not survive the hospitalization. Of those 773 patients, 721 had an admission APACHEIII score ≥63 (178 of whom died) and 52 did not survive hospitalization although they had an admission APACHE III score < 63. Of these 773 patients, 73 (9.4%) received a palliative care consultation during the ICU stay. Older age and longer ICU stay were associated with higher likelihood of palliative care consultation services among sample patients (t= −4.95, p<.001 and t= −2.48, p=.013, respectively). Not surprisingly, palliative care consultation was more frequent for those who actually died (33/230 than those who survived the hospitalization (14.2% vs. 7.2%, p=.001). No differences in ICU unit, gender, race or admitting severity of illness score were observed between palliative care consultation recipients and non-recipients. Demographic and clinical characteristics of palliative care consultation recipients and non-recipients in our sample are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of ICU Patients at High Risk of Dying and/or Died, by Receipt of Palliative Care Consultation

| Palliative Care Consult (n=73) | No Palliative Care Consult (n=700) | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mean±SD(min-max) | t | |||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 72.72±12.88(34–98) | 64.70±16.06(18–97) | −4.95 | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| APACHE III Score | 85.85±25.78(15–172) | 84.65±22.65(23–191) | −0.43 | .670 |

|

| ||||

| ICU Days* M(SD) | 13.77±7.26(4–28) | 11.56±7.23(2–28) | −2.48 | .013 |

|

| ||||

| n(%) | Χ2 | |||

|

| ||||

| Female | 40(10.5) | 342(89.5) | 0.93 | .334 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White (n=689) | 64(9.3) | 625(90.7) | 1.70 | .472 |

| Black/AA (n=74) | 9(12.2) | 65(87.8) | ||

| Other/Unknown (n=10) | 0 | 10(100) | ||

|

| ||||

| Non-survivors (n=230) | 34(14.8) | 196(85.2) | 10.91 | .001 |

|

| ||||

| Unit n(%) | ||||

| Transplant (n=168) | 10(6.0) | 158(94.0) | 10.92 | .053 |

| Neuro-trauma (n=99) | 6(6.1) | 93(93.9) | ||

| Neuro ICU (n=90) | 11(12.2) | 79(87.8) | ||

| Trauma (n=97) | 11(11.3) | 86(88.7) | ||

| Cardiovascular (n=154) | 11(7.1) | 143(92.9) | ||

| Medical (n=165) | 24(14.5) | 141(85.5) | ||

The most frequent reason listed for palliative care consultation was clarification of goals of care (71%), followed by hospice evaluation/discharge planning (27.9%) and pain/symptom management (17.9%). The referring physician was usually the attending (57.5%). The specialty or service of the referring physician was most commonly Critical Care Medicine (41%). A complete listing of reasons for consultation and referring physician specialty and role is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons for Consult and Referring Physician Specialty and Role

| Reason for Consult n(%)* | (n=73) |

|---|---|

| Pain and Symptom Management | 12(16.5) |

|

| |

| Clarification of Goals of Care | 52(71.2) |

|

| |

| Family Support | 6(8.2) |

|

| |

| Hospice Evaluation/Discharge Planning | 13(27.9) |

|

| |

| Unknown | 5(6.8) |

|

| |

| Other n(%) | |

| Per Family Request | 4(5.5) |

| Per ICU Request | 2(2.7) |

| Per Care Management/Social Work Request | 3(4.1) |

| Continuity of Care after ICU D/C | 2(2.7) |

|

| |

| Specialty or Service of Referring Physician n(%) | |

|

| |

| Critical Care Medicine (CCM) | 30(41.1) |

| Transplant | 1(1.4) |

| General Surgery/Trauma | 2(2.7) |

| General Surgery | 4(5.5) |

| Neurology | 9(12.3) |

| Neurosurgery | 2(2.7) |

| General Medicine | 3(4.1) |

| Nephrology | 1(1.4) |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 1(1.4) |

| Unknown | 20(27.4) |

|

| |

| Role of Referring Physician n(%) | |

|

| |

| Attending | 42(57.5) |

| Surgeon, non-attending | 1(1.4) |

| Physician, non-attending | 9(12.3) |

| Resident | 3(4.2) |

| Unknown | 21(28.8) |

Sum is >100% as multiple reasons for consult could be chosen.

In terms of timing and duration of the palliative care consultation among the EOL cohort, we found that patients were in the ICU for an average of nearly 9 days (62% of the total ICU stay) before receiving a palliative care consultation; and the mean duration of services was 4.6 days. Of the 73 patients receiving palliative care services, 13 (18%) had services initiated the day prior to death or discharge/transfer from ICU and 16 (21.9%) began receiving services on the day of death or discharge/transfer from the ICU. Complete statistics on timing and duration of palliative care consultation services are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Timing and Duration of Palliative Care Consultation (PCC)

| Interval (n=73) | Mean±SD(min-max) |

|---|---|

| Days elapsed to PCC | 8.89±6.02(0–26) |

| Proportion of ICU Stay* with PCC | .62±.27(0–.96) |

| Duration of PCC Services (days) | 4.64±4.11(1–20) |

| Proportion of ICU Stay* with PCC | .36±.26(.04–1.0) |

2–28 days

Patients (from both Hospital A and Hospital B) who received palliative care consultation services (N=73) received an average of 3.6 visits during the duration of consultation, most of which were from the physician (Hospital A) or palliative care service nurse (Hospital B). (At Hospital A, one patient was seen by a palliative care NP while the remainder were seen by one of the palliative care MDs. At Hospital B all of the visits were performed by the palliative care nurse as that facility did not have palliative care physicians on service.) Nearly 40% of patients received social work services and approximately 30% received services from a pastoral care provider; among palliative care service recipients, none had documentation of services from the palliative care team psychologist. Details of the number and multidisciplinary composition of palliative care provider visits are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Number and Multidisciplinary Composition of PCC* Service Visits

| Visits among PCC* recipients (n=73) | Mean±SD(min-max) |

|---|---|

| Total PCC* service visits | 3.6±2.5(1–14) |

|

| |

| Mean visits per day during consultation | 1.1±.76(.14–5.0) |

|

| |

| Diversity of PCC* Services | |

| Physician Visits | 1.26±1.56(0–6) |

| NP** Visits | .03±0.16(0–1) |

| Social Worker Visits | .60±0.92(0–4) |

| Pastoral Care Visits | .48±0.88(0–5) |

| Palliative Care Nurse Visits*** | 1.2±1.93(0–9) |

|

| |

| Patients receiving services in addition to those of MD/NP/RN | n(%) |

| Social Work | 29(39.7) |

| Pastoral Care | 23(31.5) |

| Psychology | 0 |

Palliative Care Consultation

Nurse Practitioner Visits (Hospital A)

Palliative Care Nurse Visits (Hospital B)

Discussion

This study provides insight into patterns of palliative care consultation service referral and delivery in a large sample of potentially dying and non-surviving patients from a variety of specialty ICU units and for whom we have over 15,000 patient days of care quality outcome data. Patients in our sample had a high prevalence of pain, heavy sedation, restraint and ICU-acquired pressure ulcers. And while this study did not attempt to capture information about primary (non-consultative) palliative care efforts, we observed a very low rate of referral to the sub-specialty palliative care service, with consultation typically occurring late in the course of the ICU stay. Other studies of palliative care referral patterns in hospitalized patients show similarly low rates of consultation among patients at high risk of dying or with unmet palliative care needs. Greener and colleagues report an overall palliative care consultation rate of 6% among hospitalized heart failure patients; and although they did not report the consultation rate for those in ICU, they did report a significantly greater odds of consultation (OR= 2.5) for those who had an ICU stay.25 Baldwin and colleagues, in a study of 288 older adult ICU survivors, reported that 88% of patients had at least one palliative care need, while only 6 (2.6%) had received a palliative care consultation while hospitalized.35

Efforts by individuals engaged in research, practice, and quality improvement 22, 36, 37 are ongoing to transform care for ICU patients, making it more patient-centered. However, in our findings, the majority of palliative care consultations were not made to directly address the burden of ICU care, but to clarify goals of care. This is reflective of what Bishop and colleagues describe as a “bifurcated” model, where patients traverse one of two mutually exclusive tracks, either the “cure” track or the “care” track.38 This pattern persists even though risk of dying can be known with some accuracy. In our study, the APACHE III score at 24 hours after ICU admission was a fairly good predictor of high risk of dying. (Only 52 of the 230 non-survivors in our sample fell below the APACHE-III threshold for high risk of dying.) Our findings suggest it is possible to identify a priori many of those individuals who face a high risk of having unmet palliative care needs or experiencing poor quality of dying, providing an opportunity for intervention.

Receipt of palliative care is the established standard for all ICU patients, 22, 39 and is of particular importance to patients at high risk of dying, along with their family members. Screening for unmet palliative care needs is one means of reaching this goal; however, using current screening tools and triggers, Hua and colleagues estimate conservatively, that 1 in 7 ICU patients would meet criteria for a palliative care consultation. Therefore, providing sub-specialty palliative care for those meeting criteria is simply not feasible given the current availability of specialty palliative care providers, and future needs for specialty palliative care providers will far outstrip the supply.40 Furthermore, a recent trial that utilized palliative care providers to conduct family meetings for ICU patients with chronic critical illness did not result in improved outcomes for family members.41 Strategies which seek to improve ICU care through the integration of palliative care principles and practices into the culture of care within the ICU have been recommended.16 Integrating palliative care strategies into the routine bedside care provided by nurses, physicians and other allied health professionals has the potential to benefit a greater number of patients and reach them earlier in the ICU stay. Such an approach may be the most feasible and effective means to address unmet palliative care needs for this patient population and to positively impact the quality of dying for those that do not survive hospitalization.

We must acknowledge several limitations to this study. Data on patient outcomes were abstracted from clinical documentation, the validity and reliability of which cannot be absolutely determined. The models of palliative care service delivery differed between the two clinical sites, and over the course of data collection, each site experienced programmatic changes in the palliative care program. (For example, the health system formed a system-wide institute in 2011 to increase the capacity of health system hospitals to provide high-quality palliative care through education and expertise and support.) Furthermore, this secondary analysis did not capture palliative care that was provided by non-specialists in the course of everyday care. In addition, both clinical sites were part of the same health system, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, because the parent study excluded patients who did not have sustained wakefulness during mechanical ventilation, this is a biased sample and may limit the generalizability of findings to all patients who may be dying.

These findings demonstrate the low frequency and late timing of sub-specialty palliative care consultation in a large, clinically diverse sample of ICU patients who were at high risk of dying or who died. Furthermore, the findings suggest a low rate of consultation for psychological support, pain and symptom management, or spiritual support. Given that the prevalence of pain and other distressing symptoms is known to be high for this population, new care delivery models are needed to bring the full array of palliative care practices to these patients, earlier in the course of the ICU stay.

Highlights.

We described patterns of palliative care consultation among critically ill ICU patients who were at high risk of dying and/or who died

Subspecialty palliative care consultations were late and infrequent

The majority of consultations were made for clarification of goals of care

New paradigms are needed to deliver timely palliative care to more patients

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Elise Gamertsfelder, BSN, RN for her assistance in abstracting medical record data for this project.

Funding: This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, INQRI grant [#66633,2009]; the Mayday Fund [2011]; and the National Institutes of Health [F31NR014078, 2013].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bergbom-Engberg I, Haljamae H. Assessment of patients’ experience of discomforts during respirator therapy. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1068–1072. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198910000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puntillo KA, Arai SR, Cohen NH, et al. Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2155–2160. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f267ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puntillo KA, Morris AB, Thompson CL, Stanik-Hutt JR, White CA, Wild LR. Pain behaviors observed during six common procedures: Results from Thunder Project II. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:421–427. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000108875.35298.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotondi A, Chelluri L, Sirio C, et al. Patients’ recollection of stressful experiences while receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:746–752. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorecki C, Closs SJ, Nixon J, Briggs M. Patient-reported pressure ulcer pain: A mixed-methods systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:443–459. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f267ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van de Leur J, van der Schans C, Loef B, Deelman B, Geertzen J, Zwaveling J. Discomfort and factual recollection in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2004;8:R467–R473. doi: 10.1186/cc2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strumpf NE, Evans LK. Physical Restraint of the Hospitalized Elderly: Perceptions Of Patients and Nurses. Nurs Res. 1988;37:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan-Marx E. Psychological responses to physical restraint use in older adults. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1995;33:20–25. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19950601-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cutler LR, Hayter M, Ryan T. A critical review and synthesis of qualitative research on patient experiences of critical illness. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuelson KA. Unpleasant and pleasant memories of intensive care in adult mechanically ventilated patients—Findings from 250 interviews. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27(2):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:61–69. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098029.65347.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox C, Carson S, Lindquist J, et al. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R9. doi: 10.1186/cc5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook D, Rocker G. Dying with Dignity in the Intensive Care Unit. NEJM. 2014;370:2506–2514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Herting JR, Engelberg RA. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2418–2428. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Consensus for Quality Palliative Care. National Consesus Project for Quality Palliative Care. 3. Pittsburgh PA: 2013. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):593–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, et al. Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliat Med. 2010;24(2):154–65. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, Morrison RS. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. Palliat Med. 2008;11(8):1094–102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the ICU: The nurse in a leading role. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13:89–94. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318203d9ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Position Statement on Access to Palliative Care in Critical Care Settings: A Call to Action. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angus DC, Truog RD. Toward better icu use at the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315:255–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palliative Care Services. Solutions for Better Patient Care and Today’s Health Care Delivery Challenges. Chicago: Health Research & Educational Trust; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greener DT, Quill T, Amir O, Szydlowski J, Gramling RE. Palliative care referral among patients hospitalized with advanced heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1115–1120. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Source deleted for blinded review.

- 27.Knaus W, Draper E, Wagner D, Zimmerman J. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: A study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292:2765–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. The promise of a good death. The Lancet. 1998;351:SII21–SII29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet. 360:2026–2030. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruenewald DA, White EJ. The illness experience of older adults near the end of life: A systematic review. Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;24:163–180. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall S, Chochinov H, Harding R, Murray S, Richardson A, Higginson I. A Phase II randomised controlled trial assessing the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for older people in care homes: Study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans LK, Strumpf NE. Myths about elder restraint. Image J Nurs Sch. 1990;22:124–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin MR, Wunsch H, Reyfman PA, et al. High burden of palliative needs among older intensive care unit survivors transferred to post-acute care facilities. a single-center study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:458–465. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201303-039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson JE, Bassett R, Boss RD, et al. Models for structuring a clinical initiative to enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: a report from the IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU) Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1765–1772. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8ad23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AHRQ Care and Communication Quality Measures. Vol 2014:AHRQ Care and Communication Quality Measures.

- 38.Bishop JP, Perry JE, Hine A. Efficient, compassionate, and fractured: Contemporary care in the ICU. Hastings Cent Rep. 2014;44:35–43. doi: 10.1002/hast.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.IOM. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the need for palliative care Consultation across United States intensive care units using a trigger-based model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;189(4):428–36. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. Effect of palliative care–led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:51–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]