Abstract

When grown at high light intensity, more than a quarter of the total carotenoids in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis consists of myxoxanthophyll, a polar carotenoid glycoside. The biosynthetic pathway of myxoxanthophyll is unknown but is presumed to involve a number of enzymes, including a C-3′,4′ desaturase required to add one double bond to generate 11 conjugated double bonds in the monocyclic myxoxanthophyll. A candidate for this desaturase is Slr1293, which was identified by genome similarity searching. To determine whether Slr1293 is a desaturase recognizing neurosporene and lycopene, slr1293 was expressed in Escherichia coli strains accumulating neurosporene or lycopene. Confirming such a desaturase function for Slr1293, these E. coli strains accumulated 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene and 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene, respectively. Indeed, deletion of slr1293 in Synechocystis provides further evidence that Slr1293 is a desaturase recognizing neurosporene: In the slr1293 deletion mutant, neurosporene was found to accumulate and was further processed to produce neurosporene glycoside. Neurosporene hereby becomes a primary candidate to be the branch point molecule between carotene and myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis in this cyanobacterium. The slr1293 gene was concluded to encode a C-3′,4′ desaturase that is essential for myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis, and thus it was designated as crtD. Furthermore, as Slr1293 appears to recognize neurosporene and to catalyze the first committed step on the myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway, Slr1293 plays a pivotal role in directing a portion of the precursor pool for carotenoid biosynthesis toward myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

Myxoxanthophyll [(3R, 2′S)-2′-(2,4-di-O-methyl-α-l-fucoside)-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol)] is a xanthophyll glycoside found in cyanobacteria and in some nonphotosynthetic bacteria but not in eukaryotic algae (3). It was first isolated from Oscillatoria rubrescens (15) and was proposed to be a polyhydroxy carotenoid glycoside (16). Recently, the sugar moiety of myxoxanthophyll in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was identified as dimethylated fucose, which has not been reported in carotenoid glycosides before (30). Myxoxanthophyll has a unique glycoside linkage; a hydroxy group at C-2 of the ψ end group of the carotenoid is used for the glycoside linkage. This structure is only found in myxoxanthophyll and oscillaxanthin and is limited to cyanobacteria; it has not been reported in any other bacteria or eukaryotic organisms (13, 23).

The carotenoid moiety of myxoxanthophyll, myxol (3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,1′,2′-triol), was re-ported recently in the marine bacterium P99-3 strain (previously a Flavobacterium sp.), but no carotenoid glycoside was reported in this strain and myxol was the only carotenoid that accumulated in substantial amounts (31). There is no clear evidence for how myxoxanthophyll is synthesized in cyanobacteria, although it has been proposed to start from a γ-carotene (β,ψ-carotene) molecule (30). Indeed, γ-carotene has been proposed to be an intermediate in the pathway for myxol biosynthesis in the P99-3 strain as well (31).

Myxoxanthophyll and myxol have a double bond at the C-3′,4′ position. Therefore, the biosynthetic pathway requires an enzyme that catalyzes the addition of one more double bonds between C-3 and C-4. Enzymes catalyzing a C-3′,4′ desaturation are common in organisms with C30 (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) and C40 (e.g., Rhodobacter capsulatus) carotenoids; they are known as dehydrosqualene desaturase (CrtN) and methoxyneurosporene desaturase (CrtD), respectively (1, 24). CrtN and CrtD recognize a similar region of the carotenoid molecule in spite of the difference in chain length (24). Interestingly, a bacterial CrtN was able to introduce a C-3′,4′ double bond in a hybrid C35 carotenoid pathway that was created in Escherichia coli (32). The cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 contains an open reading frame, slr1293, that is expected to encode a dehydrogenase with a conserved phytoene dehydrogenase domain. Slr1293 was annotated in ERGO (http://ergo.integratedgenomics.com/ERGO) as diapophytoene dehydrogenase (CrtN), but no experimental confirmation of such a function is available.

Other carotenoid desaturases are present as well. In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, phytoene desaturase (CrtP, Slr1254) introduces two double bonds to produce ζ-carotene (20) and has no significant similarity to other bacterial phytoene desaturases (19), which introduce three or four double bonds, producing neurosporene and lycopene, respectively (25). The cyanobacterial ζ-carotene desaturase identified in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (CrtQ, Slr0940) (5) is similar to CrtP (Slr1254) rather than bacterial phytoene desaturase (CrtI) and is restricted to the last two dehydrogenation steps (ζ-carotene to lycopene). Interestingly, the closest relative to the bacterial type desaturase (CrtI) is Slr1293.

In this work, the open reading frame slr1293 was cloned and coexpressed with the pAC-Neur and pAC-Lyc plasmids (9), which cause the accumulation of neurosporene and lycopene, respectively, in E. coli. The results of these experiments support the hypothesis that Slr1293 is a C-3′,4′ desaturase, with the enzyme apparently preferring neurosporene over lycopene. Furthermore, an slr1293 deletion mutant of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was generated to examine the function of slr1293 in its native host and to study the consequences of slr1293 deletion on myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis. The resulting mutant lacks myxoxanthophyll but contains some carotenoid glycosides with a decreased number of conjugated double bonds. We conclude that Slr1293 is indeed the C-3′,4′ desaturase required for the first committed step of myxoxanthophyll synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was cultivated on a rotary shaker at 30°C in BG-11 medium, buffered with 5 mM N-tris (hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid-NaOH (pH 8.2) and supplemented with 5 mM glucose. For growth on plates, 1.5% (wt/vol) Difco agar and 0.3% (wt/vol) sodium thiosulfate were added. For growth in liquid under light-activated heterotrophic growth conditions (2), cells were kept in complete darkness with the exception of one 15-min light period (20 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) every 24 h.

Cloning slr1293 and constructing the pΔslr1293E plasmid.

Open reading frame slr1293 of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was cloned by PCR based on the available Synechocystis genomic sequence (17). The forward primer was 5′-TGCTGTTGGAGCTCGCTCAGGG-3′, with an engineered SacI site (bold) and corresponding to bases 288884 to 288905 in CyanoBase (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano/cyano.html); the reverse primer was 5′-CATAGCTCAAGCTTATGGAAATCTC-3′, with an engineered HindIII restriction site (bold) and a sequence corresponding to CyanoBase bases 291351 to 291327 (base changes made to introduce restriction sites are italic). The PCR-amplified sequence corresponds to slr1293 with 0.4 to 0.5 kbp of flanking sequence on both sides of the open reading frame. A PCR product of the expected size (2.5 kbp) was purified and treated with restriction enzymes according to the restriction sites created on each primer. The slr1293 gene and its flanking regions were cloned into pUC19 with its SacI and HindIII sites, creating pslr1293. The slr1293 gene was deleted by restriction at the EcoRI and AvrII sites 215 bp downstream from the slr1293 start codon and 800 bp upstream from the slr1293 stop codon, respectively, and replaced by a 1.4-kb erythromycin resistance cassette from pRL425 (10) digested with EcoRI and XbaI. This created pΔslr1293E, which was used for transformation of the Synechocystis sp. to generate the Δslr1293E mutant strain.

Plasmids used for expression in E. coli.

Plasmids pAC-Lyc and pAC-Neur (9) (kindly provided by F. X. Cunningham, University of Maryland) were used to mediate the formation of lycopene (ψ,ψ-carotene) and neurosporene (7,8-dihydro-ψ,ψ-carotene), respectively, in E. coli strains BL21, JM109, and DH5α. These strains were used for introduction of slr1293 as follows. slr1293 was cloned by PCR with forward primer 5′-CCACTCCTTTTCATATGGTCCCT-3′, having an NdeI restriction site engineered at the start codon, and reverse primer 5′-CCATGAATTCCGGATCCTAGGAGTT-3′, carrying a BamHI restriction site adjacent to the stop codon. The engineered sites facilitate the cloning of slr1293 into the pET16b expression vector digested by NdeI and BamHI to create the pET16b-slr1293 plasmid. The cloned fragment was sequenced to confirm the correct sequence and orientation of the slr1293 gene. The pET16b-slr1293 plasmid was introduced into E. coli with either pAC-Lyc or pAC-Neur by electroporation, and transformants were selected for resistance to ampicillin and chloramphenicol.

Transformation and segregation analysis of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

Transformation of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was carried out as described by Vermaas et al. (33). Transformants were propagated on BG-11/agar plates supplemented with 5 mM glucose and increasing concentrations of erythromycin (5 μg/ml gradually increased to 1 mg/ml). The segregation state of the transformants was monitored by PCR with primers recognizing sequences upstream and downstream of the slr1293 coding region. Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genomic DNA used for PCR analysis of mutants was prepared as described by He et al. (14).

Extraction, separation, and analysis of carotenoids.

To analyze carotenoid production in E. coli, Luria-Bertani medium (50 ml in a 250-ml Erlenmeyer flask) containing chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml) was inoculated with 1 ml of overnight culture with cells carrying the pAC-Lyc or pAC-Neur plasmid with the pET16b-slr1293 plasmid or with the pET16b control plasmid. Cultures were grown in darkness at 28°C with shaking at 250 rpm for approximately 4 h to an optical density at 550 nm of≈0.5. Expression of slr1293 was induced with 0.5 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellets were first saponified by 6% KOH in methanol and then extracted with methanol once and then with a methanol-methyl chloride mixture (1:1, vol/vol) until the pellets were colorless. The extracts were combined, and the carotenoid pigments were eluted from the methanol-methylene chloride mixture by diethyl ether. Diethyl ether fractions were neutralized by washing with water. The diethyl ether extracts were evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen and resolubilized in methanol.

To determine the carotenoid content of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, cells were harvested by centrifugation from cultures in the exponential growth phase (optical density at 730 nm of ≈0.5). Cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried. Pigments were extracted from freeze-dried cells by three successive extractions with 100% methanol containing 0.1% NH4OH, and the extracts were combined. Carotenoid extraction was performed in darkness under N2 on ice.

For high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, carotenoid extracts from E. coli or Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen until the samples were dry. Dried samples were redissolved in a small volume of methanol containing 0.1% NH4OH and immediately subjected to HPLC on an HP-1100 with a Waters Spherisorb S5 ODS2 (4 mm by 250 mm) analytical column filled with C18 reversed-phase silica gel, with a linear 18-min gradient of ethyl acetate (0 to 95%) in acetonitrile-water-triethylamine (9:1:0.01, vol/vol/vol) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The absorption spectra of the eluted pigments were recorded continuously by an online photodiode array detector in the 280- to 665-nm range.

For mass spectroscopy analysis of carotenoids, carotenoids were separated on a semipreparative Waters Spherisorb S10 ODS2 (10 mm by 250 mm) HPLC column filled with C18 reversed-phase silica gel. For separation, a linear 18-min gradient of ethyl acetate (0 to 90%) and methyl chloride (0 to 5%) in acetonitrile-water-triethylamine (9:1:0.01, vol/vol/vol) was utilized at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. Collected xanthophyll fractions were further purified by a Waters Spherisorb S5 ODS2 (4 mm by 250 mm) analytical column with a linear 25-min gradient of ethyl acetate (0 to 60%) in acetonitrile-water-triethylamine (9:1:0.01, vol/vol/vol) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Samples were evaporated under nitrogen and analyzed immediately or stored under nitrogen at −80°C until use. Dried carotenoids were dissolved in 20 μl of methyl chloride; 10 μl was mixed with 1 μl of terthiophene (used as a matrix) dissolved in acetone, 1 μl of this mixture was spotted for mass analysis, and mass spectra were obtained by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF)-mass spectrometry (Voyager DE STR Biospectrometry Work Station). Carotenoids were identified based on their spectral properties, retention time, and molecular mass (28, 29).

RESULTS

Proteins similar to Slr1293.

Slr1293 is apparently a member of the carotenoid desaturase and isomerase family. The protein is 30% identical to CrtH (Sll0033; carotene isomerase) and 23% identical to CrtO (Slr0088; β-carotene ketolase) from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Slr1293 is similar to bacterial phytoene desaturase (CrtI) (about 20% identity with CrtIs from different bacteria). The primary sequence of Slr1293 shows 19% identity to a known C-3′,4′ desaturase (CrtD) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides (18) and 20% identity with the putative CrtD from the marine bacterium P99-3, which produces myxol (31). Orthologues of Slr1293 (47 to 67% identity) were found in all other cyanobacteria with sequenced genomes to date, including Prochlorococcus marinus MIT 9313, Synechococcus sp. strain WH 8102, Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120, Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS 101, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP 1, and Prochlorococcus marinus MED 4.

Expression analysis of slr1293 in E. coli.

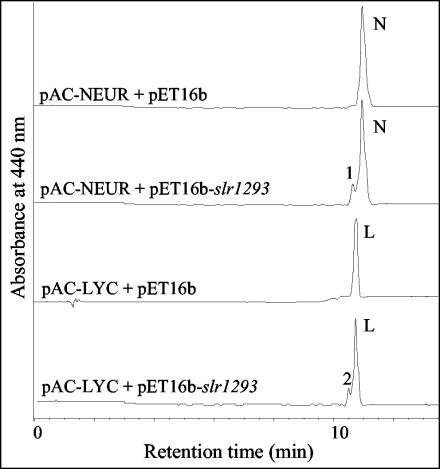

The carotenoids produced in E. coli DH5α carrying pAC-Neur (9) and pET16b-slr1293 of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 were extracted and separated with a C18 column. The carotenoid profile indicates that neurosporene was the major carotenoid accumulated due to the expression of the gene cluster in pAC-Neur (Fig. 1). However, a small band (peak 1) to the left of the neurosporene peak was found to have a large spectral shift (λmax = 450, 475, and 505 nm) versus neurosporene (λmax = 420, 441, and 470 nm) (Fig. 2A). The spectral properties of the newly formed carotenoid suggest that two additional double bonds were added to the nine conjugated double bonds of neurosporene to yield a 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene (3′,4′-didehydro-7,8-dihydro-ψ,ψ-carotene) (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 1.

HPLC analysis of carotenoid extracts from E. coli with pAC-Neur or pAC-Lyc and with pET16b-slr1293 or pET16b as a control. Pigment detection was by monitoring absorption at 440 nm. N, neurosporene; L, lycopene; 1, 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene; 2, 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene.

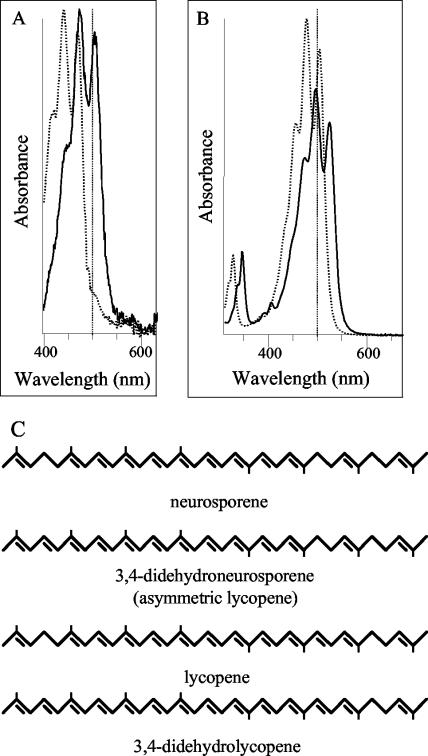

FIG. 2.

Absorption spectra of the carotenoids extracted from E. coli with plasmids pAC-Neur (A) or pAC-Lyc (B) and pET16b-slr1293. (A) Carotenoids were neurosporene (peak N in Fig. 1; dotted line; λmax = 420, 441, 470 nm; III/II = 76%) and 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene (peak 1 in Fig. 1; solid line; λmax = 450, 475, and 505 nm; III/II = 77%). (B) Carotenoids were lycopene (peak L in Fig. 1; dotted line; λmax = 440, 475, and 505 nm; III/II = 70%) and 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene (peak 2 in Fig. 1; solid line; λmax = 466, 492, and 527 nm; III/II = 60%). To simplify the interpretation of panels A and B, a vertical line has been introduced to indicate the 500-nm position in the spectra. (C) Structures of 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene and 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene interpreted to be present in E. coli carrying pAC-Neur and pET16b-slr1293 or pAC-Lyc and pET16b-slr1293, respectively.

The HPLC spectra of carotenoids from E. coli with the pAC-Lyc and pET16b-slr1293 plasmids (Fig. 1) showed a carotenoid species on the left shoulder of the lycopene peak (peak 2). This new species showed a bathochromic shift (λmax = 466, 492, and 527 nm) relative to lycopene (λmax = 450, 475, and 505 nm) (Fig. 2B). The wavelength maxima of peak 2 are suggestive of 13 conjugated double bonds (6, 29). These spectral properties suggest that compound is 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene (3′,4′-didehydro-ψ,ψ-carotene) (Fig. 2C).

Deletion of slr1293 in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803.

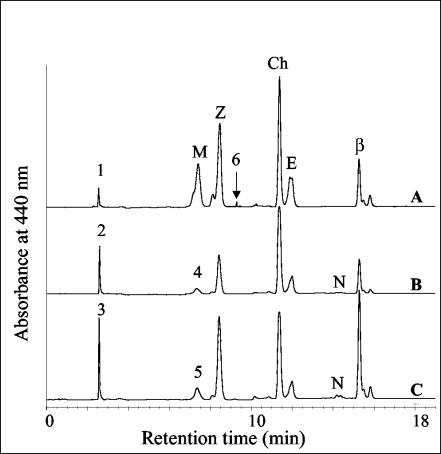

The Δslr1293E mutant strain of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was generated to study the role of Slr1293 in carotenoid biosynthesis, especially that of myxoxanthophyll. In wild-type Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, four major carotenoids, β-carotene (β,β-carotene), echinenone (β,β-carotene-4-one), zeaxanthin [(3R,3′R)-β,β-carotene-3,3′-diol], and myxoxanthophyll, accumulated in substantial amounts (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we observed a fifth species in the wild type (peak 1; Fig. 3), and the amounts of compounds with similar mobility were increased in the Δslr1293E mutant (peaks 2 and 3, Fig. 3) and other mutants that were impaired in myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis (Δsll1213Z and Δslr1125S mutants; H. Mohamed and W. Vermaas, unpublished observations).

FIG. 3.

HPLC analysis of pigment extracts from wild-type Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (A) grown at 40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 and those from the Δslr1293E mutant grown at 0.5 (B) and 40 (C) μmol photons m−2 s−1. Cultures were grown photomixotrophically; detection was at 440 nm. Known carotenoids are myxoxanthophyll (M), zeaxanthin (Z), echinenone (E), and β-carotene (β). Ch, chlorophyll. Numbered peaks correspond to unknown compounds with absorption spectra resembling those of carotenoids. Peaks 4 and 5 are new carotenoid glycosides in the Δslr1293E mutant with molecular masses different from that of myxoxanthophyll (Table 1).

The peaks were collected and subjected to mass analysis. Interestingly, the mass of the carotenoid found in peak 1 was 584 m/e (Table 1), which is identical to that of myxol. However, its spectral properties (λmax = 475 and 503 nm; III/II = 28%) (III/II refers to the ratio of the amplitude of the third and second peaks of the absorption) (29) were different from those of myxol (λmax = 450, 477, and 509 nm; III/II = 58%) (16) and show a spectrum indicating cis-isomerization contributions (7). Therefore, the carotenoid found in peak 1 is probably an isomer form of myxol. In the Δslr1293E mutant, the masses of the carotenoids in peaks 3 and 2 were higher by 2 and 4 mass units (m/e = 586 and 588; Table 1) than the myxol-like species found in the wild type (peak 1; m/e = 584). Therefore, the carotenoids in peaks 2 and 3 are related to myxol but are changed in their structure, presumably due to the lack of the Slr1293 protein.

TABLE 1.

Molecular mass of selected carotenoids accumulated in the wild type and the Δslr1293E mutant

| Peak no.a | Mass (m/e) | Matching formula | Tentative identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 584 | C40H56O3 | Myxol |

| 2 | 588 | C40H60O3 | Trihydroxy neurosporene |

| 3 | 586 | C40H58O3 | Trihydroxy lycopene |

| 4 | 737 | C45H69O8 | Neurosporene fucoside |

| 5 | |||

| Carotenoid 1 | 746 | C46H66O8 | Monomethyl carotenoid glycoside |

| Carotenoid 2 | 760 | C47H68O8 | Dimethyl carotenoid glycoside |

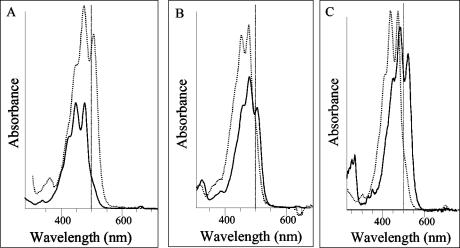

Fractionation of the major carotenoids in the Δslr1293E mutant grown at 0.5 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 3B) showed the presence of zeaxanthin, echinenone, and β-carotene. However, the compound present at the location of the myxoxanthophyll peak showed spectral properties that were different from that of myxoxanthophyll (λmax = 420, 441, and 477 nm, III/II = 98%, versus myxoxanthophyll, λmax = 453, 477, and 509 nm, III/II = 58%) (Fig. 4A). These spectral properties are indicative of nine conjugated double bonds in compound 4 of the mutant, and we interpret it to be a neurosporene derivative. Its molecular mass (m/e = 737 [H+ +736]; Table 1) is compatible with a nonmethylated neurosporene fucoside (2′-[α-l-fucoside]-1′,2′,7′,8′-tetrahydro-ψ,ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol) (calculated m/e = 736). Protonation during mass analysis may explain the difference between the recorded and calculated masses.

FIG. 4.

(A) Absorption spectra of myxoxanthophyll (dotted line; λmax = 453, 477, and 509 nm; III/II = 58%) and the carotenoid (solid line; λmax = 420, 443, and 477 nm; III/II = 98%) accumulated in peak 4 (Fig. 3B) of the Δslr1293E mutant grown at low light intensity (0.5 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). (B) Absorption spectra of the carotenoid species found in the Δslr1293E mutant grown at 40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 3C). Peak 5 (Fig. 3C) consists of at least two compounds with different spectra and masses (Table 1); a lycopene glycoside (solid line; λmax = 455, 479, and 507 nm, III/II = 18%) and an isomer (dotted line) with λmax = 443 and 469 nm. (C) Absorption spectra of carotenoid intermediates. A carotenoid with 12 conjugated double bonds (peak 6 in Fig. 3A; solid line; λmax = 307, 355, 461, 489, and 519 nm; III/II = 52%) recorded in the wild type only versus neurosporene, which was detectable in the Δslr1293E mutant (peak N in Fig. 3 B and C; dotted line; λmax = 423, 443, and 471 nm). To simplify the interpretation of this figure, a vertical line has been introduced in the spectra to indicate the 500-nm position.

However, when the mutant was grown at a light intensity of 40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, a different set of myxoxanthophyll-like carotenoids comigrating with myxoxanthophyll (peak 5 in Fig. 3C) were synthesized. Mass analysis of these carotenoids in the Δslr1293E mutant showed two different carotenoids (m/e = 746 [(3R,2′S)-2′-(2-mono-O-methyl-α-l-fucoside)-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol]) and 760 [(3R,2′S)-2′-(2,4-di-O-methyl-α-l-fucoside)-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol] (Table 1) in peak 5 that comigrated with myxoxanthophyll in the wild type. This suggests that these are myxoxanthophyll derivatives with an extra saturation. A one-step desaturation (−2 H) of these carotenoid glycosides (m/e 746 and 760) is required to produce myxol mono-[(3R,2′S)-2′-(2-mono-O-methyl-α-l-fucoside)-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,1′-diol] and dimethyl fucoside (m/e 744 and 758), respectively. Accordingly, the carotenoid glycosides synthesized at a light intensity of 40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 in the Δslr1293E mutant lack one double bond, providing additional evidence that a specific, one-step desaturase activity is missing from the mutant.

Evidence from carotenoid intermediates.

The HPLC solvent system used in this study was able to resolve potential low-abundance carotenoid biosynthesis intermediates. Among these potential intermediates was a carotenoid species (peak 6 in Fig. 3A) apparently with 12 conjugated double bonds (λmax = 307, 355, 461, 489, and 519 nm) (Fig. 4C) that accumulated in the wild type but was not found in the Δslr1293E mutant (the small HPLC peaks at a similar position in the mutant [Fig. 3B and C] are presumably due to chlorophyll degradation products, based on their absorption spectra). Conversely, in the mutant, a peak accumulated (peak N in Fig. 3B and C) that, according to its spectrum and elution profile, was neurosporene. Interestingly, in order for C40 carotenoid species to accommodate 12 conjugated double bonds, a combination of two different secondary modifications is necessary, a C-3′,4′ desaturation and a C-1′,2′ saturation leading to introduction of two OH groups. As these two modifications occur only in the myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway, this intermediate is interpreted to be in the myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway. The lack of this intermediate in the Δslr1293E mutant indicates that a C-3′,4′ desaturase is absent in the Δslr1293E mutant.

DISCUSSION

Function of Slr1293.

Comparative genomic analysis led to the hypothesis that slr1293 codes for a dehydrogenase with C-3′,4′ desaturase activity. Dehydrogenase and desaturase function is compatible with the conserved GXGXXG motif near the N terminus (20). This gene is well conserved in all cyanobacterial genomes available in the public database. Representatives of these cyanobacterial genera synthesize myxoxanthophyll, oscillaxanthin [(2R,2′R)-2,2′-di-(l-chinovosyloxy)-3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydro-1,2,1′,2′-tetrahydro-ψ,ψ-carotene-1,1′-diol] and aphanizophyll [2′-(l-chinovosyloxy)-3′,4′-didehydro-1′,2′-dihydro-β,ψ-carotene-3,4,1′-triol] carotenoids (13), all of which require a C-3′,4′ desaturation step. Indeed, the hypothesis that Slr1293 is CrtD, a C-3′,4′ desaturase on the pathway toward myxoxanthophyll, was supported by the experiments in this study, as discussed below.

As indicated in Fig. 1, introduction of slr1293 into an E. coli strain accumulating neurosporene led to the production of a new compound with red-shifted absorption (Fig. 2A). The red shift is compatible with a desaturase activity of Slr1293, leading to an increase in the number of conjugated double bonds in the carotenoid. Two desaturation sites are feasible. One is addition of a double bond at the C-7,8 position to produce lycopene. However, the spectrum of the Slr1293-catalyzed product is clearly not that of lycopene (Fig. 2A). Lycopene can be produced by a CrtQ-catalyzed reaction (11) or a four-step bacterial desaturase (12), but these two enzymes are not available in this system. The second position where a double bond may be introduced is the C-3′,4′ position, leading to an asymmetric lycopene (3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene) (Fig. 2C). The absorption fine structure of the experimentally observed compound (III/II = 82%) is in line with the notion that the carotenoid has an asymmetric distribution of the conjugated double bonds, thus increasing the absorption fine structure of the carotenoid. Therefore, we conclude that Slr1293 catalyzes desaturation at the C-3′,4′ position.

In the E. coli strain accumulating lycopene, introduction of Slr1293 again led to a new compound with a red-shifted absorption spectrum (Fig. 2B). Introduction of a double bond at the C-3′,4′ position of the carotenoid (Fig. 2C) led to 13 conjugated double bonds rather than 11, as in lycopene. This explains the shift in the absorption spectrum. As the HPLC mobility of the desaturated compound has not been altered much relative to lycopene, no hydroxy groups appear to have been introduced in the carotenoid. Therefore, we conclude that the newly formed carotenoid in Slr1293-containing E. coli accumulating lycopene is 3′,4′-didehydrolycopene, in line with our interpretation in the previous paragraph that Slr1293 possesses CrtD (C-3′,4′ desaturase) activity. However, in E. coli, neurosporene and lycopene conversion by this enzyme was only partial. This might indicate that neurosporene and lycopene are not native substrates for this enzyme and/or that the enzyme requires the presence of other subunits or cofactors for full activity. Nonetheless, the results provide strong evidence that the protein encodes a C-3′,4′ desaturase.

The slr1293 gene of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is the only gene known to date that affects the biosynthesis of the carotenoid backbone of myxoxanthophyll without affecting the other main carotenoids (β-carotene, zeaxanthin, and echinenone). Interestingly, in the Δslr1293E mutant, neurosporene accumulated to a measurable degree (Fig. 3C, peak N) and the carotenoid glycoside synthesized in the mutant had the neurosporene chromophore (λmax = 420, 443, and 477 nm; III/II = 98%; Fig. 4A) (peak 4 in Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the carotenoid in peak 2 (Fig. 3B) is suggested to be trihydroxy neurosporene based on its mass (588 versus 584 m/e for myxol in the wild type) (Table 1). The interpretation of this observation is that deletion of slr1293 results in the accumulation of neurosporene, which becomes available as a substrate for hydratases and glycosylases (e.g., CrtC and CrtX) later in the pathway. These enzymes exhibit a higher catalytic promiscuity than those located earlier in the pathway (26, 27). Therefore, neurosporene is further processed to form the polyhydroxy (m/e 588) and glycosylated (m/e 736; λmax = 420, 443, and 477 nm; III/II = 98%) forms in the Δslr1293E mutant.

In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, a glycoside with cis-isomerization (λmax = 443 and 469 nm with a III/II ratio of >100%) (Fig. 4B) that is very close to neurosporene accumulated when slr1293 had been deleted; this observation raises the possibility that a specific cis-isomer may be required for the desaturation reaction catalyzed by Slr1293. Furthermore, this isomer form may introduce structural asymmetry in the molecule, so that lycopene cyclase can recognize only one side of the carotenoid. As a result, only monocyclic carotenoids would be produced from such a cis-isomer and serve in the myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway. This provides an interesting perspective regarding the poor activity of the expressed Slr1293 protein in E. coli. The substrate of Slr1293 may be a tri-cis-isomer (6) (similar in spectrum to what is shown in Fig. 4B) that is present in the native system but not in E. coli. For example, the carotene isomerase (CrtH) (4, 22) encoded by sll0033 may have a role in providing the proper isomer required for Slr1293 and thus control the ratio of the precursors for monocyclic versus bicyclic carotenoids in this cyanobacterium.

The accumulation of a carotenoid isomer in the Δslr1293E strain together with the close similarity between Slr1293 and a carotene isomerase (CrtH) may indicate that Slr1293 is another carotene isomerase in this cyanobacterium. If this is the case, then a desaturase (such as CrtP or CrtQ) might carry out the C-3′,4′ desaturation, and Slr1293 might provide the substrate in the appropriate conformation. However, this would not explain the formation of desaturated lycopene or neurosporene upon overexpression of Slr1293 in E. coli carrying the pAC-Neur or pAC-Lyc plasmid. Moreover, heterologous expression of CrtP and CrtQ in E. coli did not show CrtD-like activity (6, 9). In addition, the activity of another carotene isomerase (Sll0033) was dispensable in the light, presumably because of photoisomerization (22). However, continuous light at 40 or 80 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 did not functionally complement Slr1293 activity in the Δslr1293E mutant (Fig. 3). Whereas Slr1293 may have an intrinsic isomerization activity to facilitate the C-3′,4′ desaturation reaction, we interpret the data presented in this paper to indicate that Slr1293 is a desaturase; Sll0033 thereby may be an isomerase that depends on desaturation and saturation for its activity.

In the Δslr1293E mutant, the sugar appears to be attached first to a myxol-type component, and subsequently methylation is carried out; intermediates with zero, one, or two methyl groups are detected (Table 1). The molecular structure of the carotenoid appears to affect the catalytic efficiency of the methyl transferase (CrtF) that is involved in methylation of the fucose group; with neurosporene as the carotenoid moiety the fucose is not methylated at a light intensity of 0.5 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, whereas fucose methylation was 50% efficient in the case of carotenoid glycosides synthesized at 40 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. Therefore, the as yet unknown myxoxanthophyll methyltransferase seems to be fairly specific with respect to the carotenoid part of myxoxanthophyll.

Myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway.

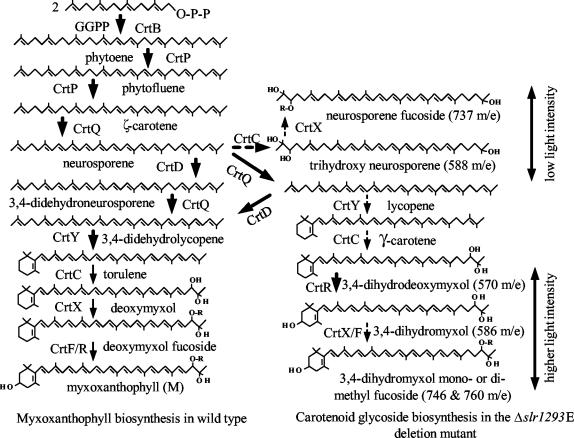

Based on the carotenoids present in the Δslr1293E mutant, a proposed pathway for myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis and for the formation of the newly formed carotenoid glycosides is illustrated in Fig. 5. Upon growth at low light intensity, accumulation of neurosporene glycoside in the Δslr1293E mutant indicates that enzymes of the myxoxanthophyll pathway can process neurosporene; a carotene hydratase (CrtC) and a glycosyl transferase (CrtX) generate the nonmethylated carotenoid glycoside (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the neurosporene derivative was not methylated; this observation suggests a specificity of the methylase for myxol-type compounds that are desaturated at the C-7,8 position.

FIG. 5.

Putative myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis pathway in the wild type (left) and alternative pathways leading to novel carotenoids in the Δslr1293E mutant (right). Compounds have been assigned based on their absorption spectra (Fig. 4), HPLC elution profile (Fig. 3), and mass analysis (Table 1). Bold arrows refer to enzymes that are known in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (CrtB, phytoene synthetase; CrtP, phytoene desaturase; CrtR, carotene hydroxylase; and CrtQ, ζ-carotene desaturase); thin arrows correspond to hypothetical steps catalyzed by enzymes that have not yet been identified in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (CrtY, lycopene cyclase; CrtC, carotene hydratase; CrtX, glycosyl transferase; and CrtF, methyl transferase); and dotted arrows indicate alternative routes for the biosynthesis of carotenoid glycosides recorded in the absence of Slr1293 (CrtD). GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate.

Based on the presence of neurosporene glycoside and trihydroxyneurosporene in the Δslr1293E mutant, neurosporene is likely to be the natural substrate for the Slr1293 protein in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, where molecules to be used for myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis branch off from the common carotenoid biosynthesis pathway. The addition of a C-3′,4′ double bond to neurosporene results in only one side being available for lycopene cyclase (8). Therefore, the cyclization product of 3′,4′-didehydroneurosporene is expected to produce only monocyclic carotenoids. Interestingly, in vitro, the C-3′,4′ desaturase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides shows a higher specificity toward neurosporene than toward lycopene and a low activity with γ-carotene as a substrate (1). Also, the γ-carotene produced in E. coli by the novel lycopene monocyclase of the P99-3 strain (31) was not desaturated to form torulene (3′,4′-didehydro-β,ψ-carotene) by a CrtD-like protein that is encoded in the carotenoid gene cluster of P99-3. Whereas this may be due to expression difficulties or to the absence of the proper isomer, a likely explanation is that γ-carotene is a poor substrate for CrtD. In the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, Slr1293 may have a regulatory role in steering early carotenoid precursors toward either myxoxanthophyll or the other carotenoid species synthesized in this cyanobacterium. The slr1293 gene is concluded to encode a C-3′,4′ desaturase that is essential for myxoxanthophyll biosynthesis, and thus it was designated crtD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, M., A. Ruther, and G. Sandmann. 1997. Purification and biochemical characterization of a hydroxyneurosporene desaturase involved in the biosynthetic pathway of the carotenoid spheroidene in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 179:7462-7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, S. L., and L. McIntosh. 1991. Light-activated heterotrophic growth of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803: a blue-light-requiring process. J. Bacteriol. 173:2761-2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, G. A. 1994. Eubacteria show their true colors: genetics of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis from microbes to plants. J. Bacteriol. 176:4795-4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitenbach, J., A. Vioque, and G. Sandmann. 2001. Gene sll0033 from Synechocystis 6803 encodes a carotene isomerase involved in the biosynthesis of all-E lycopene. Z. Naturforsch. 56c:915-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitenbach, J., B. Fernández-González, A. Vioque, and G. Sandmann. 1998. A higher-plant type ζ-carotene desaturase in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plant Mol. Biol. 36:725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitenbach, J., G. Braun, S. Steiger, and G. Sandmann. 2001. Chromatographic performance on a C30-bonded stationary phase of mono hydroxycarotenoids with variable chain length or degree of desaturation and of lycopene isomers synthesized by different carotene desaturases. J. Chromatogr. 936:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britton, G., S. Liaaen-Jensen, and H. Pfander. 1998. Carotenoids: biosynthesis and metabolism, vol. 3. Birkhauser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland.

- 8.Cunningham, F. X., and E. Gantt. 2001. One ring or two? Determination of ring number in carotenoids by lycopene epsilon-cyclases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2905-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham, F. X., Z. Sun, D. Chamovitz, J. Hirschberg, and E. Gantt. 1994. Molecular structure and enzymatic function of lycopene cyclase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC 7942. Plant Cell 6:1107-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elhai, J., and C. P. Wolk. 1988. A versatile class of positive-selection vectors based on the nonviability of palindrome-containing plasmids that allows cloning into long polylinkers. Gene 68:119-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández-González, B., G. Sandmann, and A. Vioque. 1997. A new type of asymmetrically acting β-carotene ketolase is required for the synthesis of echinenone in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9728-9733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser, P. D., N. Misawa, H. Linden, S. Yamano, K. Kobayashi, and G. Sandmann. 1992. Expression in Escherichia coli, purification and reactivation of the recombinant Erwinia uredovora phytoene desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:19891-19895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwin, T. W. 1980. The biochemistry of the carotenoids, vol. 1, plants, 2nd ed. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 14.He, Q., D. Brune, R. Nieman, and W. Vermaas. 1998. Chlorophyll a synthesis upon interruption and deletion of por coding for the light-dependent NADPH. Eur. J. Biochem. 253:161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilbron, I. M., and B. Lythgoe. 1936. The chemistry of the algae. II. The carotenoid pigments of Oscillatoria rubrescens. J. Chem. Soc. 516:1376-1380. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertzberg, S., and S. Liaaen-Jensen. 1969. The structure of myxoxanthophyll. Phytochemistry 8:1259-1280. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko, T., S. Sato, H. Kotani, A. Tanaka, E. Asamizu, Y. Nakamura, N. Miyajima, M. Hirosawa, M. Sugiura, S. Sasamoto, T. Kimura, T. Hosouchi, A. Matsuno, A. Muraki, N. Nakazaki, K. Naruo, S. Okumura, S. Shimpo, C. Takeuchi, T. Wada, A. Watanabe, M. Yamada, M. Yasuda, and S. Tabata. 1996. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 3:109-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang, H. P., R. J. Cogdell, S. Takaichi, and C. N. Hunter. 1995. Complete DNA sequence, specific Tn5 insertion map, and gene assignment of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 177:2064-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linden, H., N. Misawa, T. Saito, and G. Sandmann. 1994. A novel carotenoid biosynthesis gene coding for zeta-carotene desaturase: functional expression, sequence and phylogenetic origin. Plant Mol. Biol. 24:369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Férez, I. M., and A. Vioque. 1992. Nucleotide sequence of the phytoene desaturase gene from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and characterization of a new mutation which confers resistance to the herbicide norflurazon. Plant Mol. Biol. 18:981-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masamoto, K., O. Zsiros, and Z. Gombos. 1999. Accumulation of zeaxanthin in cytoplasmic membranes of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 grown under high light condition. J. Plant Physiol. 155:136-138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masamoto, K., H. Wada, T. Kaneko, and S. Takaichi. 2001. Identification of a gene required for cis-to-trans carotene isomerization in carotenogenesis of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 42:1398-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niggli, U., and H. Pfander. 1999. Carotenoid glycosides and glycosyl esters, p. 125-145. In R. Ikan (ed.), Naturally occurring glycosides. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom

- 24.Raisig, A., and G. Sandmann. 2001. Functional properties of diapophytoene and related desaturases of C30 and C40 carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1533:164-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandmann, G. 1994. Carotenoid biosynthesis in microorganisms and plants. Eur. J. Biochem. 223:7-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandmann, G. 2002. Combinatorial biosynthesis of carotenoids in a heterologous host: a powerful approach for the biosynthesis of novel structures. Chem. Biochem. 3:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandmann, G. 2003. Combinatorial biosynthesis of novel carotenoids in E. coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 205:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takaichi, S. 1993. Usefulness of field desorption mass spectrometry in determining molecular masses of carotenoids, natural carotenoid derivatives and their chemical derivatives. Org. Mass Spectrom. 28:785-788. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaichi, S., and K. Shimada. 1992. Characterization of carotenoids in photosynthetic bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 213:374-385. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaichi, S., T. Maoka, and K. Masamoto. 2001. Myxoxanthophyll in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is myxol 2′-dimethyl-fucoside, (3R,2′S)-myxol 2′-(2,4-di-O-methyl-l-fucoside), not rhamnoside. Plant Cell Physiol. 42:756-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teramoto, M., S. Takaichi, Y. Inomata, H. Ikenaga, and N. Misawa. 2003. Structural and functional analysis of a lycopene beta-monocyclase gene isolated from a unique marine bacterium that produces myxol. FEBS Lett. 545:120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umeno, D., and F. H. Arnold. 2003. A C35 carotenoid biosynthetic pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3573-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermaas, W. F. J., J. G. K. Williams, and C. J. Arntzen. 1987. Sequencing and modification of psbB, the gene encoding the CP-47 protein of photosystem II, in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Mol. Biol. 8:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]