Abstract

Although Lactococcus is one of the most extensively studied lactic acid bacteria and is the paradigm for biochemical studies of citrate metabolism, little information is available on the regulation of the citrate lyase complex. In order to fill this gap, we characterized the genes encoding the subunits of the citrate lyase of Lactococcus lactis CRL264, which are located on an 11.4-kb chromosomal DNA region. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed a cluster of eight genes in a new type of genetic organization. The citM-citCDEFXG operon (cit operon) is transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA of 8.6 kb. This operon carries a gene encoding a malic enzyme (CitM, a putative oxaloacetate decarboxylase), the structural genes coding for the citrate lyase subunits (citD, citE, and citF), and the accessory genes required for the synthesis of an active citrate lyase complex (citC, citX, and citG). We have found that the cit operon is induced by natural acidification of the medium during cell growth or by a shift to media buffered at acidic pHs. Between the citM and citC genes is a divergent open reading frame whose expression was also increased at acidic pH, which was designated citI. This inducible response to acid stress takes place at the transcriptional level and correlates with increased activity of citrate lyase. It is suggested that coordinated induction of the citrate transporter, CitP, and citrate lyase by acid stress provides a mechanism to make the cells (more) resistant to the inhibitory effects of the fermentation product (lactate) that accumulates under these conditions.

Many bacteria can utilize citrate under fermentative conditions. The citrate pathway has been extensively studied in enterobacteria (4, 26). In all known citrate fermentation pathways, after its uptake into the cell, citrate is split into acetate and oxaloacetate by the enzyme citrate lyase. In Klebsiella pneumoniae the citrate-specific fermentation genes form a cluster of two divergent operons (4, 26). This cluster includes the genes citDEF, encoding the citrate lyase subunits γ, β, and α, and the citS gene, encoding a citrate H2−/Na1+ proton motive force-dissipating transporter. Associated with this cluster, K. pneumoniae contains the oadGAB genes, encoding the biotin oxaloacetate decarboxylase, which allows growth with citrate as the sole carbon and energy source (Fig. 1). In Escherichia coli, the cit cluster includes the genes encoding citrate lyase and the CitT citrate/succinate antiporter (22) (Fig. 1). In this bacterium the citrate fermentation is dependent on the presence of an oxidable cosubstrate, due to the lack of genes encoding an oxaloacetate decarboxylase activity. Thus, citrate is converted via malate and fumarate to succinate, and the reducing equivalents required for this conversion are provided by the oxidation of glucose or glycerol (14). In both organisms, the citrate fermentation (cit) clusters are regulated by a sensor kinase, CitA, and a response regulator, CitB (4).

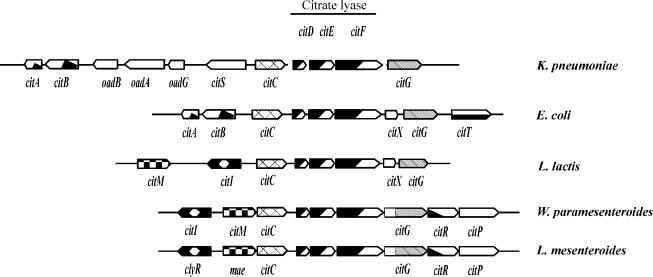

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of cit genes involved in citrate utilization in K. pneumoniae (4), E. coli (22), L. mesenteroides (2), W. paramesenteroides (20), and L. lactis IL-1403 (The Institute for Genome Research). The shaded box indicates that the organization of the citDEF genes is highly conserved in the different cit clusters.

Like in K. pneumoniae, in lactic acid bacteria the pathway involved in the conversion of citrate to pyruvate requires three specific enzymatic activities: a citrate permease, a citrate lyase, and an oxaloacetate decarboxylase (9). In several strains of Lactococcus lactis, the ability to transport citrate has been associated with an 8.0-kb family of plasmids, which carry the citQRP operon, whereas in Leuconostoc spp., the gene involved in citrate transport is linked to 23-kb plasmids (9, 19, 27). We have recently reported that in Weissella paramesenteroides J1 (previously named Leuconostoc paramesenteroides), the citP gene, encoding the citrate permease, is carried on plasmid pCitJ1 (19, 20). This gene is part of the citMCDEFGRP operon, which also encodes the α, β, and γ subunits of the citrate lyase complex (citF, citE, and citD genes, respectively) and the complementary activities required for the biosynthesis and activation of the prosthetic group (citG and citC genes) (19, 20) (Fig. 1). The expression of the plasmid-carried citMCDEFGRP operon in W. paramesenteroides J1 is induced when the cells are grown in the presence of citrate, and this induction depends on the transcriptional activator CitI (19, 20). Analogous organization and regulation have also been shown for the chromosomal cit cluster from Leuconostoc mesenteroides 195 (2) (Fig. 1).

In contrast to the case for the citrate-regulated genes from Weissella and Leuconostoc, the expression of the L. lactis citP gene is not influenced by the presence of citrate in the growth medium (15). Instead, the expression of this gene is induced at a transcriptional level by acidification of the medium (8). We have previously reported that in L. lactis the citrate fermentation pathway has an important physiological role, allowing cells to improve the cometabolism of glucose and citrate at low pH and to detoxify the lactate accumulated at the end of the exponential growth phase (17).

Although citrate lyase catalyzes the first committed step in citrate metabolism, little is known about the regulation of the genes encoding this important enzyme in L. lactis. In this paper we describe the identification of a chromosomal citM-citCDEFXG operon of L. lactis CRL264 that contains the genes encoding the three subunits of the citrate lyase and the citM gene, encoding a protein that is highly homologous to malic enzymes. We also show that the expression of the citM-citCDEFXG operon as well as the citrate lyase activity is increased when cells are grown under acidic pH conditions. These results suggest that in L. lactis the pH-controlled transcriptional regulation of the citrate fermentation pathway has evolved as a mechanism of resistance to acidic pH conditions. In addition, we provide information suggesting that CitI could be involved in the regulation of the citM-citCDEFXG and citQRP operons in L. lactis CRL264.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. L. lactis strains were grown at 30°C in a pH-controlled fermentor in M17 broth containing 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (M17G) at pH 7.0 or 5.0. The fermentor (Bioflo110 fermentor bioreactor; New Brunswick Scientific). The pH was continuously monitored and kept constant with 1 M NaOH solution. Alternatively, cells of L. lactis were grown in batch culture at 30°C without shaking in M17G adjusted to pH 7.0 or pH 5.0 with HCl (8). To analyze the induction of the cit operon expression by citrate, M17G medium was supplemented with 1% sodium citrate (M17GC). Cells of L. lactis were grown under stress conditions (300 mM NaCl, 1 mM H2O2, or 37°C) in M17G at an initial pH of 7.0. E. coli was grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (24). Erythromycin (1 μg/ml, for L. lactis) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml, for E. coli) was added to the medium when necessary.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this work

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Characteristics, genotype, or sequencea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| L. lactis subsp. lactis strains | ||

| CRL264 | Lac+ Pro+ Cit+; harboring pCit264 | 27 |

| IL-1403 | Trp+; plasmid free | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pL1 | 1.2-kb PCR amplification fragment containing citE and 5′ end of citF from L. lactis CRL264 cloned in pUC19 vector | This work |

| pL2 | 5.3-kb HindIII fragment containing citI, citCDE, and 5′ end of citF cloned in pBScSK(−) vector | This work |

| pL5 | 2.5-kb EcoRI fragment containing citX, citG, and 3′ end of citF cloned in the pUC18 vector | This work |

| pGEMT264 | 1.4-kb PCR amplification product corresponding to citM gene cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector | This work |

| pHPB21 | pAK80-derived plasmid containing the lacLM genes under control of the 2.5-kb cit promoter region from L. lactis CRL264 | This work |

| pHPB22 | pAK80-derived plasmid containing the lacLM genes under control of the 0.4-kb cit promoter region from L. lactis CRL264 | This work |

| pHPB11 | pAK80-derived plasmid containing the lacLM genes under control of the P1 and P2 promoters of the citQRP operon from L. lactis CRL264 | This work |

| pHPB41 | pAK80-derived plasmid containing the lacLM genes under control of the PcitI promoter of the citI gene from L. lactis CRL264 | This work |

| pHPB42 | pAK80-derived plasmid containing the lacLM genes under control of the putative PcitC from L. lactis CRL264 | This work |

| pFS21 | 8-kb pCit264 plasmid cloned in the EcoRI site of pUC18 vector | 27 |

| pAK80 | Promoter selection vector containing the promotorless L. mesenteroides β-galactosidase (lacL and lacM) genes | 10 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| CL1 | 5′-TTTAGATCTAACNATGATGTTYGTNCCNGG-3′ | This work |

| CL2 | 5′-ACCAGATCTAGTDATRTTNGTNACNACNCC-3′ | This work |

| MAE264U | 5′-AGGAAAGAGGATCCATGGTTGATTTTAATAAAG-3′ | This work |

| MAE264L2 | 5′-TCCAAGCTTTGAAAAACTTGCTGG-3′ | This work |

| PCIT264O | 5′-TAATTAAGCTTCCTTTGGACTATTCTG-3′ | This work |

| P264U2 | 5′-ATGTAGAGAAGCTTCAAAAAAATAATGCACTCC-3′ | This work |

| P264L | 5′-TCGGATCCTTGTGTATTTGCGTTTAGC-3′ | This work |

| RegIU | 5′-CCACTGCAGATCAAATCCATTC-3′ | This work |

| RegCL | 5′-GCAAGTCTGCAGGTATTTTAT | This work |

| CitI264U | 5′-AACTGCAGCTTTCTATGTTACAACTCTGC-3′ | This work |

| RI264L | 5′-AAACATTCAAATGCAAATCC-3′ | This work |

| RI264U | 5′-AAATCTTGTGCCAAATTGG-3′ | This work |

| pMM264 | 5′-AATATCCAATACACCTGTGTG-3′ | This work |

The restriction sites included in the oligonucleotides are underlined.

Construction of plasmids.

In order to clone the citrate lyase genes, degenerate oligonucleotide primers (CL1 and CL2 [Table 1]) designed from the amino acid sequences of the α and β subunits of the citrate lyase of L. mesenteroides (2) were used for PCR amplification from genomic DNA from L. lactis CRL264. The 1.2-kb amplification product containing the 5′ ends of the citE and citF genes was purified, digested with BglII, and cloned into the BamHI site of pUC19 vector to give the plasmid pL1 (Fig. 2; Table 1). This fragment was used as a probe in a Southern blot experiment, and a 5.3-kb HindIII fragment of chromosomal DNA was identified and cloned into pBScSK(−) to give the pL2 plasmid (Fig. 2; Table 1). With the 298-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pL2 as a probe, a 2.5-kb EcoRI fragment of genomic DNA was identified in Southern blot experiment and cloned into pUC18 to give pL5 (Fig. 2; Table 1). E. coli harboring the pL2 and pL5 plasmids was screened by colony hybridization with the 1.2-kb PCR product from pL1 and the 298-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pL2, respectively, as probes. When the L. lactis IL-1403 genome sequence was available (3), we used the annotated sequence to design oligonucleotide primers for cloning the remaining cit region of L. lactis CRL264. The pGEMT264 plasmid was constructed by cloning a 1.4-kb fragment including the citM gene and 3′ adjacent region into pGEM-T Easy vector (Fig. 2; Table 1). This fragment was obtained by PCR amplification with the MAE264U (nucleotides [nt] +24 to +56 from the transcriptional start site) and MAE264L2 (complementary to nt +1443 to +1420 from the transcriptional start site) (Table 1) primers. To construct the pHPB21 plasmid, a 2.7-kb DNA fragment containing the 5′ end of the citM gene and the 2.5-kb upstream region of that gene was amplified by using the primers PCIT264O (nt −2478 to −2451 from the transcriptional start site) and P264L (complementary to nt +220 to +194 from the transcriptional start site) (Table 1). This product was purified, digested with HindIII and BamHI, and cloned in the pAK80 vector (10). The 570-bp PCR product obtained by using the oligonucleotides P264U2 (nt −348 to −316 from the transcriptional start site) and P264L was digested with HindIII and BamHI and cloned in the pAK80 vector to construct the pHPB22 plasmid. The 864-bp amplification product containing the intergenic region between citC and citI was obtained employing the RegIU and RegCL primers (Fig. 2; Table 1). The DNA product was digested with PstI and cloned into the same site of the plasmid pAK80. Both orientations of the putative promoter regions, PcitI and PcitC, were isolated by restriction pattern, giving plasmids pHPB41 and pHPB42, respectively. In all cases, standard protocols were used for PCR. The reaction mixture contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, a 25 mM concentration of each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2 U of Deep Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), 20 pmol of each primer, and 50 ng of DNA in a final volume of 50 μl. Typically, samples were subjected to 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 1 min), annealing (54°C, 1 min), and extension (72°C, 1 min). An additional round of amplification (72°C, 20 min) in the presence of 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) and 25 mM dATP was performed in the case of the 1.4-kb fragment containing the citM gene in order to enhance pGEM-T Easy cloning efficiency (plasmid pGEMT264).

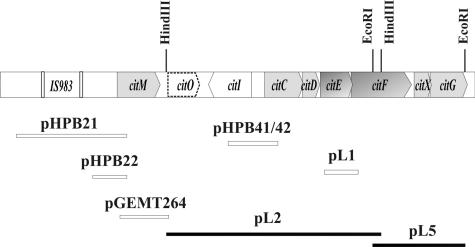

FIG. 2.

Cloning of the cit locus of L. lactis CRL264. A schematic representation of the lactococcal inserts present in the recombinant plasmids pL1, pL2, pL5, pHPB21, pHPB22, pHPB41, pHPB42, and pGEMT264 is shown. Solid bars indicate chromosomal fragments identified by colony hybridization (pL2 and pL5); open bars indicate DNA fragments obtained by PCR amplification (see details in Materials and Methods and Table 1).

To construct the pHPB11 plasmid, the 3.6-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment from pFS21 (27) containing the citQRP promoters was purified and cloned into the pAK80 vector (Table 1).

DNA analysis and manipulation.

Plasmid DNA from E. coli cells was prepared with a Wizard Plus Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega). Plasmid DNA extractions from lactic acid bacteria were done as described by O'Sullivan and Klaenhammer (21). Treatment of DNA with restriction-modification enzymes was performed as recommended by the suppliers. L. lactis transformation was performed by electroporation according to the procedure of Dornan and Collins (7). E. coli cells were transformed by the standard CaCl2 procedure (24).

The complete DNA sequence of the citrate cluster was determined with automated DNA sequencing instrumentation at the University of Maine DNA sequencing facility from pL1, pL2, pL5, pGEMT264, pHPB41, pHPB42, pHPB21, and pHPB22 (Fig. 2; Table 1).

β-galactosidase assay.

The β-galactosidase activity was measured as described by Israelsen et al. (10).

Citrate lyase activity assay.

To determine citrate lyase activity, lactococcal cultures were grown in M17G at either pH 7.0 or 5.0 to an absorbance of 0.3 at 660 nm. Cells were harvested and resuspended in ice-cold 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) supplemented with 3 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride protease inhibitor (Sigma). Total protein extracts were prepared by passing cells three times through a French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 25 min. Citrate lyase activity was determined from samples of these extracts containing 100 or 50 μg of total soluble proteins at 25°C in a coupled spectrophotometric assay with malate and lactate dehydrogenases as described by Bekal-Si Ali et al. (2). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as 1 pmol of citrate converted to acetate and oxaloacetate per min per μg of total protein.

RNA isolation and analysis.

For Northern blot and primer extension analysis, RNA was isolated by the method described by Raya et al. (23). The RNAs were checked for their integrity and yield of the rRNAs in all samples. The patterns of the rRNAs were similar in all preparations. Total RNA concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometry and by gel quantification with Gel Doc 1000 (Bio-Rad). Primer extension analysis was performed as previously described (13). The primer used for detection of the start sites of the cit operon and citI were pMM264 and RI264U, respectively (Table 1). One picomole of the primer was annealed to 15 μg of RNA. Primer extension reactions were performed by incubation of the annealing mixture with 20 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) at 42°C for 60 min. Determination of the sizes of the reaction products was carried out in 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea. Extension products were detected by autoradiography on Kodak X-Omat S film.

For Northern blot analysis, samples containing 10 μg of total RNA were separated in a 1% agarose gel. Transfer of nucleic acids to nitrocellulose membranes and hybridization with radioactive probes were performed as previously described (13). The single-stranded probes used were synthesized as follows. The 1,170-bp BamHI fragment from pGEMT264 containing the citM gene and the 1,200-bp SalI fragment from pL2 containing the 3′ end of citE and the 5′ region from citF were gel purified and α-32P labeled in one strand by using a Sequenase kit (Promega). Primer MAE264L2 and T3 reverse primer were then used to give probes I and II, respectively (Fig. 3; Table 1). The 1,086-bp fragment containing the citI gene was obtained by PCR amplification with CitI264U and RI264L (Table 1). The fragment was purified and α-32P labeled in one strand by using the CitI264U oligonucleotide to give probe III (see Fig. 7). The reaction mixture included 0.02 pmol of DNA; 0.3 pmol of oligonucleotide; 0.3 mM (each) dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 0.7 μM unlabeled dATP; and 1 μl of [α-32P]dATP. mRNA molecular sizes were estimated by using 0.28- to 6.58-kb RNA markers (Promega).

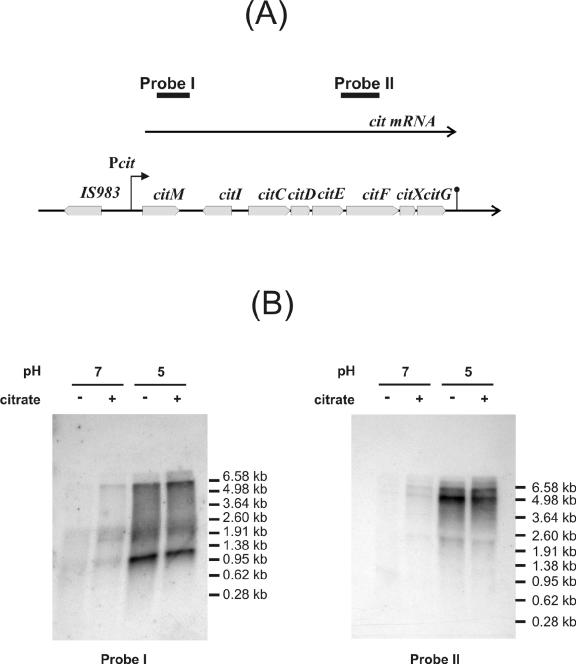

FIG. 3.

Organization of the cit operon in L. lactis CRL264 (A) and Northern blot analysis of the cit operon (B). (A) The 11.4-kb DNA cluster encompassing eight genes involved in citrate utilization is shown at the top. Pcit, promoter of the cit operon. The secondary structure downstream from citG represents a putative Rho-independent transcriptional terminator. Probe I includes a 1.2-kb fragment of citM. Probe II includes a 1.0-kb fragment of citEF. (B) Northern blot analysis was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Strain CRL264 was grown at pH 7.0 or 5.0 in the presence or absence of citrate. mRNA molecular marker are showed on the right of each autoradiograph.

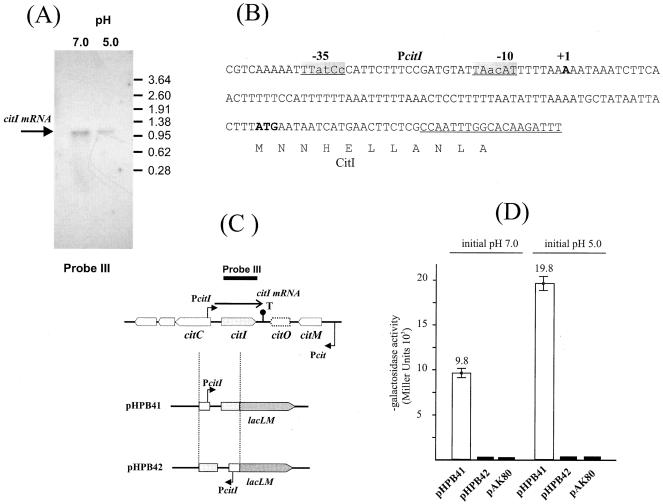

FIG. 7.

Analysis of the expression of citI in L. lactis CRL264. (A) Northern blot analysis of the citI gene. The probe (probe III) used in this experiment is indicated at the top of panel C. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the citC-citI intergenic region. −10 and −35 regions are indicated by grey boxes; +1 represents the transcription initiation site (the oligonucleotide used in the primer extension experiment is underlined). The ATG codon is in boldface. (C) Schematic representation of the pAK80-derived plasmids pHPB41 and pHPB42. Pcit and PcitI are the promoters of the citM-citCDEFXG operon and citI, respectively. T, putative Rho-independent transcriptional terminator. (D) The β-galactosidase activities of L. lactis IL-1403 cells bearing plasmids were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The initial pHs at which the cells were grown are indicated. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of L. lactis CRL264 that contains the cit region has been deposited at the GenBank database under accession no. AY268077.

RESULTS

Analysis of the chromosomal region containing the citM-citCDEFXG operon.

We determined the complete nucleotide sequence of a 11.4-kb region comprising the cit loci present in L. lactis strain CRL264 and found that the cluster containing the genes coding for citrate lyase possessed 99% of identity with the corresponding genes of L. lactis IL-1403 (3) (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1 and 2). Examination of the complete nucleotide sequence of the citrate cluster from L. lactis CRL264 revealed the presence of eight open reading frames (ORFs). On the basis of their homology with the previously characterized citrate lyase genes from enterobacteria (4, 26), six of these ORFs were identified as citC, citD, citE, citF, citX, and citG (Fig. 2). The citC gene encodes a protein of 346 amino acids that shows high homology to the acetate:SH-citrate lyase ligase, which is involved in the activation of the prosthetic group of the citrate lyase complex. The start codon of the citD gene is located 4 bp upstream of the stop codon of citC and encodes a protein of 96 amino acids (11.5 kDa). The citE gene, which starts 1 bp downstream of the stop codon of citD, encodes a protein of 304 amino acids (36.5 kDa). The start codon of the citF gene is located 23 bp upstream of the stop codon of citE, and from this DNA sequence we deduced a product of 518 amino acids (62.2 kDa). The citD, citE, and citF genes encode the three citrate lyase subunits, γ (acyl carrier protein [ACP]), β (citryl-ACP oxaloacetate lyase), and α (acetyl-ACP:citrate ACP-transferase), respectively. High homology was found between the structural subunit α, β, and γ proteins and the corresponding proteins present in others citrate-fermenting microorganisms. The citX gene starts 56 bp downstream from the stop codon of citF, and the inferred protein has 172 amino acids (20.6 kDa). Finally, the citG gene overlaps the citX coding region by 8 nt. The sequence derived from citG was 274 amino acids long (32.9 kDa). These genes encode the enzymes needed for the synthesis of the prosthetic group of the citrate lyase (CitX [apo-citrate lyase phosphoribosyl-dephospho-coenzyme A transferase] and CitG [triphosphoribosyl-dephospho-coenzyme A synthase]).

Preceding the first ATG of citC, citD, citE, citF, citX, and citG, putative ribosomal binding sites complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA from L. lactis were observed. The overlapping found between the citC-citD, citD-citE, citE-citF, and citX-citG genes suggests the existence of translational coupling for these genes.

citM should encode a 40.5-kDa polypeptide. This protein showed homology with malic enzyme, which is associated with the cit cluster in other lactic acid bacteria (Fig. 1). Downstream from citM and on the complementary strand we found an ORF (citI) encoding a protein that shows high homology to several transcriptional regulators. Among them, the proteins that had the highest homology were the cit operon activator CitI from W. paramesenteroides (20), the ClyR putative regulator from L. mesenteroides (2), and a putative CitI protein from Clostridium perfringens. Between the citM and citI genes we found a pseudogene (citO) which shows several frameshift mutations (Fig. 2). The analysis of its sequence reveals homology to the malate permease from Oenococcus oeni (GI:5870596) and Clostridiuim cellulovorans (GI:7363467). However, the frameshift mutations that accumulated during evolution indicate that citO is a nonfunctional gene. It is interesting that a full copy of the insertion element IS983 was found adjacent to the cit cluster (Fig. 2), which is a distinctive feature of L. lactis CRL264 compared with the cit cluster of L. lactis IL-1403.

The activity of citrate lyase from L. lactis CRL264 is induced by acid stress.

Previous reports indicate that in several bacteria the activity of citrate lyase is induced by the presence of citrate in the growth medium (2, 4, 20). To test whether this induction also takes place in L. lactis CRL264, citrate lyase activity in cell extracts from cultures grown in M17G or M17GC at pH 7.0 was analyzed. The citrate lyase activities observed in cultures grown in the absence or presence of citrate were 0.19 ± 0.04 and 0.22 ± 0.06 U/min · μg of protein, respectively. These results indicate that citrate is not an inducer of citrate lyase in L. lactis. Taking into account previous results demonstrating a higher citrate consumption in L. lactis cells grown under acidic conditions (17), we decided to analyze the citrate lyase activity in extracts of cells grown at neutral or acidic pH. The citrate lyase activities were 0.19 ± 0.04 and 1.22 ± 0.06 U/min · μg of protein in extracts of cells grown at pH 7.0 or 5.0, respectively. Therefore, the citrate lyase activity levels were increased about sixfold at acidic pH, as was also demonstrated for the activity of the plasmid-encoded citrate transporter CitP (8, 17).

Transcriptional analysis of the citrate cluster of L. lactis CRL264.

To study the transcriptional pattern of the cit cluster and to test whether its transcriptional activity is regulated by external pH, a Northern blot analysis was performed. Total cellular RNA was isolated from cultures of L. lactis CRL264 grown in M17G at pH 7.0 or pH 5.0 in the presence or absence of citrate. The RNA was hybridized with two α-32P-labeled single-stranded DNA probes (Fig. 3). Probe I includes a fragment of 1,170 nt covering the citM gene, and probe II corresponds to a 1,200-nt fragment including the 3′ end of citE and the 5′ region of citF. Probe I revealed the presence of an 8.6-kb mRNA and smaller RNA species. With probe II we observed at least six transcripts, the largest one having a size of 8.6 kb (Fig. 3). Considering the size of the cit gene cluster, the largest RNA specie detected (8.6 kb) with the two probes would correspond to an operon starting upstream from citM and ending downstream from citG (Fig. 3). The 3′ extreme of this transcript contains an inverted repeated sequence (cAGUucagACUGGGGAGccacuCUCCUCaAGUacGCUUUUU [underlining shows nucleotides involved in the complementary interaction; lowercase letters represent internal loops]; ΔG°, −10.1 kcal/mol) (28), which could act as a Rho-independent terminator (Fig. 3). The transcriptional pattern of the cit operon shown in Fig. 3 suggests that the 8.6-kb transcript could be subject to specific processing. Although below we demonstrate the absence of promoters upstream of citC, we cannot discard possibility of the existence of alternative promoters in other regions of the cit operon.

As shown in Fig. 3, the transcription of the cit operon was dramatically increased when the cells were grown at acidic pH. It is worth noting that the presence of 1% citrate in the growth medium did not significantly affect transcription of the cit operon compared with the induction produced by the acidification of the medium (Fig. 3). These results indicate that, similarly to the plasmid citP gene of L. lactis CRL264, transcription of the chromosomal cit cluster is induced by low pH (8).

Analysis of the promoter region and determination of the transcriptional start site of the citM-citCDEFXG operon.

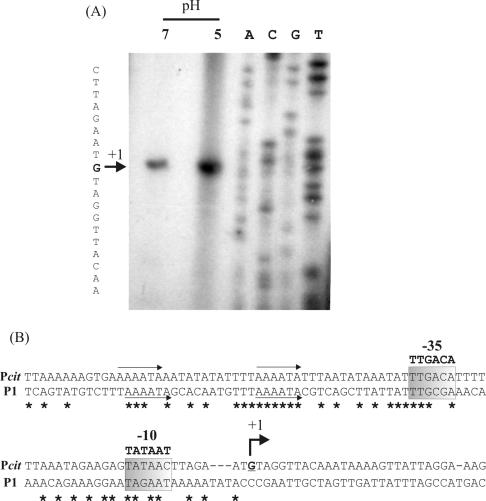

To determine if the synthesis of the 8.6-kb transcript is driven by a putative promoter located upstream from citM, the transcriptional start site of citM-citCDEFXG was determined by primer extension. Total RNA was extracted from L. lactis CRL264 cells grown in M17G at pH 7.0 or 5.0, and a primer extension assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 4A, the transcript starts with a guanosine residue located 37 bp upstream from the ATG codon of citM, and, as expected, the levels of the extended products were higher in RNA preparations from cultures grown at pH 5.0 than in those from cultures grown at pH 7.0. Analysis of this region allowed us to identify a standard promoter sequence with consensus −35 TTGACA and −10 TATAAC boxes (Fig. 4B). The presence of these −35 and −10 sequences suggests that this promoter could be recognized by the L. lactis σ39 transcription factor (1). The region upstream from the −35 box (position −35 to −94) contains an unusually high A+T content (near 95% A+T), which may contribute to the activity of the cit promoter (Pcit promoter) due to the intrinsic curvature of these A+T-rich sequences (12).

FIG. 4.

Identification of the transcriptional start site of the cit operon from L. lactis CRL264. (A) The autoradiograph shows primer extension experiments performed with total RNA extracted from cells grown in M17G medium buffered at pH 7.0 or 5.0. Lanes A, C, G, and T, sequencing ladders. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the chromosomal citM-citCDEFXG operon promoter region (Pcit) and the plasmid citQRP promoter region (P1) from L. lactis CRL264. −10 and −35 promoter elements are shaded in gray. Consensus promoter sequences recognized by the L. lactis σ39 transcription factor are indicated over these boxes. The bent arrow indicates the transcriptional start site of the citM-citCDEFXG transcript at the residue in boldface, defined as +1. Identity between the promoter regions is indicated with asterisks. Thin arrows indicate putative binding sites that are conserved in both regions.

In Fig. 4B we compare the two pH-controlled promoter regions from L. lactis strain CRL264: the chromosomal Pcit region and the previously described plasmid promoter P1, present in the citQRP operon (8). This alignment shows several A+T-rich stretches at the same positions with respect to the −35 box in both promoters, which may be involved in the regulation of these operons by external pH.

Expression of the cit operon from L. lactis is enhanced under acidic conditions.

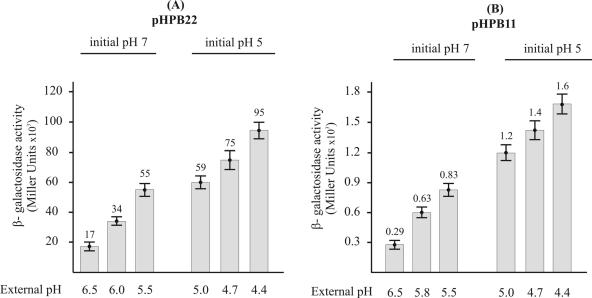

L. lactis IL-1403 harboring plasmid pHPB22 or pHPB11 was used to analyze the activity of the pH-regulated promoters Pcit and P1. Plasmids pHPB22 and pHPB11, derivatives of the pAK80 vector, contain a fusion of the lacLM reporter genes from Leuconostoc to the Pcit and P1 promoters, respectively. The β-galactosidase activities driven by each lactococcal promoter region were analyzed as a function of the external pH. To this end, cells were grown in batch culture in M17G medium at an initial pH of 5.0 or 7.0. Samples were taken at different growth stages, and the external pH was determined. As shown in Fig. 5, the β-galactosidase levels of both fusions increased about fivefold as the external pH decreased from 6.5 to 4.4. In order to analyze the influence of the growth phase of the cultures on the transcriptional activities of both promoters, we performed similar experiments in a pH-controlled fermentor. To this end, the cells were cultured at a fixed pH of 7.0 or 5.0, and samples were taken at different stages of growth until the cultures reached stationary phase. The β-galactosidase activities measured in L. lactis IL-1403(pHPB11) at a fixed pH of 5.0 at the early exponential (t1), exponential (t2), and stationary (t3) phases of growth were 1.5 × 103, 1.4 × 103, and 1.6 × 103 Miller units, respectively, while the β-galactosidase levels of this strain at pH 7.0 were 330, 305, and 215 Miller units at t1, t2, and t3, respectively. The β-galactosidase activities of strain L. (pHPB22) growing at pH 5.0 were 5.5 × 104 Miller units at t1, 6 × 104 Miller units at t2, and 5.6 × 104 Miller units at t3, while the β-galactosidase levels of this strain at pH 7.0 were 1.16 × 104 Miller units at t1, 1.3 × 104 Miller units at t2, and 1.35 × 104 Miller units at t3. These data confirm that the transcriptional induction driven from both promoters occurs at low pH independently of the growth phase.

FIG. 5.

Influence of a shift in the external pH on expression of cit-lacLM fusions. L. lactis IL-1403 containing pHPB22 (A) or pHPB11 (B) was grown in M17G adjusted to an initial pH of 7.0 or 5.0. Samples were taken at different growth stages, and the external pHs are indicated on the bottom. β-Galactosidase was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar shows the average and standard deviation of the values from at least three experiments.

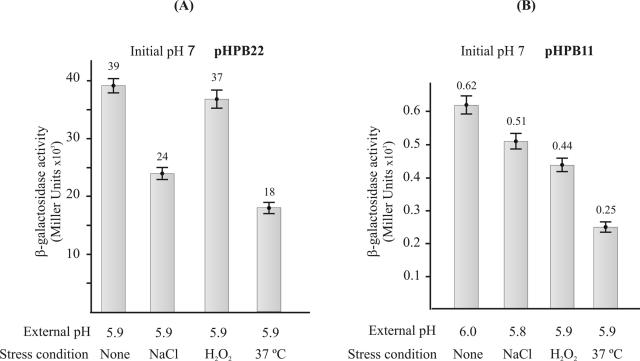

To investigate whether the response of the Pcit and P1 promoters is specific to the acidic stress, we tested the ability of several environmental stresses to induce the expression of the cit-lacLM fusions in L. lactis. We assayed the β-galactosidase activities of strains L. lactis IL-1403(pHPB22) and L. lactis IL-1403(pHPB11) upon exposure to NaCl, H2O2, and heat stress in a medium with an initial pH of 7.0. As shown in Fig. 6 none of these stress conditions induced the expression of the Pcit and P1 promoters at pH 7.0. Further, these conditions did not abolish the acid stress induction of the transcriptional fusions (data not shown). These results confirmed the specificity of the acid stress to induce transcription of two key operons involved in citrate fermentation in L. lactis CRL264.

FIG. 6.

Influence of diverse environmental stresses on expression of cit-lacLM fusions. L. lactis IL-1403 transformed with pHPB22 (A) or pHPB11 (B) was grown to an A660 of 0.7 in M17G at pH 7.0 in the presence of NaCl (300 mM), in the presence of H2O2 (1 mM), or at 37°C, and β-galactosidase activity was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 5.

To investigate whether the insertion sequence IS983, located upstream from the citM-citCDEFXG operon, had any influence on its transcription, we compared the β-galactosidase activities from cells transformed with plasmids pHPB21 (containing IS983) and pHPB22 (devoid of IS983) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). No difference in the β-galactosidase activities could be found between these two fusions when the cells were grown in M17G or M17GC under neutral or acidic conditions (data not shown). Thus, IS983 does not seem to play any role in citM-citCDEFXG transcription, as is the case for IS982 in plasmid pCit264 of L. lactis CRL264 (16).

The citI gene is transcribed as a monocistronic mRNA.

As shown in Fig. 3, the L. lactis cit operon contains citI, which displays high homology with the previously described citI gene from W. paramesenteroides strain J1, coding for a transcriptional regulator of the citMCDEFGRP operon (19, 20). However, in L. lactis, citI is oriented reverse to the cit operon (Fig. 1 and 2). To investigate the transcriptional pattern of expression of citI in L. lactis, total cellular RNA was isolated from cultures of strain CRL264 grown in M17G at pH 7.0 or 5.0. The RNA was hybridized with a single-stranded [α-32P]DNA-labeled probe corresponding to citI. As shown in Fig. 7A, a 1-kb citI mRNA could be visualized in the Northern blot experiment. The amount of mRNA detected by this technique was larger in RNA preparations from cultures grown at pH 7.0 than in those from cultures grown at pH 5.0. Thus, in contrast to the expression of the cit operon, this gene seems not to be induced by acidic pH. However, as found for the cit operon, expression of the citI gene was not influenced by addition of citrate to the growth medium (data not shown). The transcriptional start site of citI was determined by primer extension experiments from total RNA of cells of L. lactis grown in M17G at pH 7.0. The transcript starts with an adenosine residue located 117 bp upstream from the ATG of citI. The promoter is situated upstream of this sequence, with −35 (TTatCc) and −10 (TAacAT) motifs separated by a short sequence of 17 nt. These hexamers deviate three and two residues, respectively, from lactococcal consensus sequences, suggesting that the PcitI promoter could be independent of σ39, the major σ sigma factor of L. lactis (1) (Fig. 7B). A putative Rho-independent terminator sequence was found in the 3′ region of citI (cauaGAAAGAGGCauuuaaGCCUUUUUUUUcuguuau; ΔG°, −10.6 kcal/mol) (28). To test whether there are divergent promoters in the intergenic fragment located between citC and citI, we cloned this fragment in the direction of either citI or citC transcription into the pAK80 promoter probe vector, giving plasmids pHPB41 and pHPB42, respectively. The resulting plasmids contain a fusion of the lacLM reporter gene to the PcitI promoter (pHPB41) or the putative PcitC promoter (pHPB42). The β-galactosidase activities of strains bearing these plasmids were determined in cells grown in M17G medium at an initial pH of 7.0 or 5.0 (Fig. 7D). Surprisingly, the β-galactosidase activity driven by pHPB41 was twofold higher in cells growing at pH 5.0 than in cells growing at pH 7.0, showing that the PcitI promoter is induced by acidic pH. These results are in conflict with the data obtained by Northern blotting (Fig. 7A), which indicated that the citI transcript was not induced at low pH. These experiments suggest that the levels of the citI transcript are controlled in some way at a posttranscriptional level. On the other hand, when L. lactis IL-1403 was transformed with plasmid pHPB42, carrying the PcitC-lacLM fusion, the levels of β-galactosidase activity were similar to that found in lactococcal cells transformed with the pAK80 vector (Fig. 7D), indicating the absence of promoters in this region.

DISCUSSION

Three functions possibly implicated in pH homeostasis have been characterized in lactococci to date: (i) the H+-ATPase, (ii) the arginine deiminase pathway, and (iii) a glutamate decarboxylase. The H+-ATPase expels protons from the cell via ATP hydrolysis. This activity increases as the pH decreases, and it has been demonstrated that it is essential for cell viability at low pH (11, 12). The arginine deiminase pathway converts arginine to ammonia, ornithine, and CO2. Ammonia production may contribute to survival at low extracellular pH by neutralization of the medium (5, 18). Glutamate decarboxylase (GadB) converts glutamate to γ-aminobutyrate and CO2 in an H+-consuming reaction contributing to pH homeostasis (25). These three mechanisms may reduce acidification of the internal compartment and thus could be important in survival under acidic conditions. However, regulation of the expression of these pH-controlled stress response systems remains essentially unknown for lactococci. In this work, we have characterized at a molecular level a new system involved in pH homeostasis in L. lactis, the citrate fermentation pathway.

We have identified an 11.4-kb chromosomal region in L. lactis CRL264 that includes eight genes involved in the citrate fermentation pathway, organized in an operon which is transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA of approximately 8.6 kb (the cit operon). Similar large transcripts encompassing all of the genes for citrate utilization were also reported for the cit operons from W. paramesenteroides (20), L. mesenteroides (2), and K. pneumoniae (4). Several distinct smaller mRNA species were detected in addition to the full-length transcript (Fig. 3). The abundance of the smaller species indicates that they are more stable than the full-length transcript. A putative cit operon mRNA processing could explain the existence of the minor species of mRNA, as described for the cit operons present in other bacteria (2, 4, 20).

The transcriptional start point (tsp) of the citM-citCDEFXG operon was identified upstream from citM by primer extension analysis. In this region we could find −35 (TTGACA) and −10 (TATAAC) boxes, separated by 17 bp, with similarity to the sequences recognized by the L. lactis σ39 transcriptional factor (1). In addition, sequence analysis of this promoter region revealed an extremely high A+T content, which may cooperate with the activity of Pcit promoter due to the intrinsic bending of A+T sequences. However, no −10 extended motif, as described for about half of the lactococcal promoters, could be found in this operon. The alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the Pcit and P1 promoters allowed us to find direct repeats placed at the same positions from the −35 box (Fig. 4B). These direct repeats could be the binding site of a regulatory protein, suggesting a common regulatory mechanism for these two operons.

To compare the transcriptional activities of Pcit and P1, the β-galactosidase activities shown in Fig. 5 were corrected on the basis of the number of copies of each promoter in L. lactis CRL264. The number of copies of plasmid pCit264 in this strain was estimated to be about seven (10), while there is only one chromosomal copy of the citM-citCDEFXG operon in this strain. Thus, the transcriptional activity of the Pcit chromosomal promoter seems to be about fivefold higher than that of the plasmid P1 promoter.

We have evidence to prove that both plasmid operon (citQRP) encoding the citrate transporter and the chromosomal operon (citM-citCDEFXG) encoding the citrate lyase complex have similar responses to acid stress (8) (Fig. 3). In fact, the transcription of both operons is induced at acidic pH and it is not significantly influenced by the presence of citrate (Fig. 3). In agreement with this observation, the citrate lyase activity is increased in extracts obtained from cells grown at pH 5.0 compared with cells grown at pH 7.0. We have also shown that exposure to different stress conditions failed to induce the expression of the citM-citCDEFXG and citQRP operons. Moreover, the induction is independent of the growth phase, as demonstrated by experiments performed in a pH-controlled fermentor. Thus, these two key operons involved in citrate fermentation in L. lactis CRL264 are specifically induced by acidic stress.

How could the transcription of the L. lactis cit operon be regulated by pH? In this report we have shown that the activity of the citI promoter, whose putative gene product is highly homologous to the citrate-regulated CitI transcriptional activator from W. paramesenteroides, is increased twofold at acidic pH. Thus, it could be possible that when L. lactis cells detect a decrease in external pH, transcription of citI is induced, resulting in an increase in the cellular levels of CitI. If this is the case, a small increase in citI transcription could account for a larger increase in the cit mRNA detected in L. lactis under acidic conditions. The levels of citI then could be down regulated through a not-yet-identified posttranscriptional mechanism, resulting in a decrease of the cit transcript. It is worth noting that the 8.6-kb cit transcript includes a citI sequence complementary to the citI mRNA. In fact both, the mRNA sense transcript and the citI antisense transcript located in the cit operon were confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR experiments with primers CitI264U (Table 1) and CitI264L (5′-TAGGATCCTTATGAATAATCATGAACTTCTCG-3′ [the BamHI site is underlined]), respectively (data not shown). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that citI translation could also be down regulated by an antisense mechanism. Clearly, more experiments are necessary to elucidate the role, if any, of CitI in transcriptional induction of the cit operon by acidic pH.

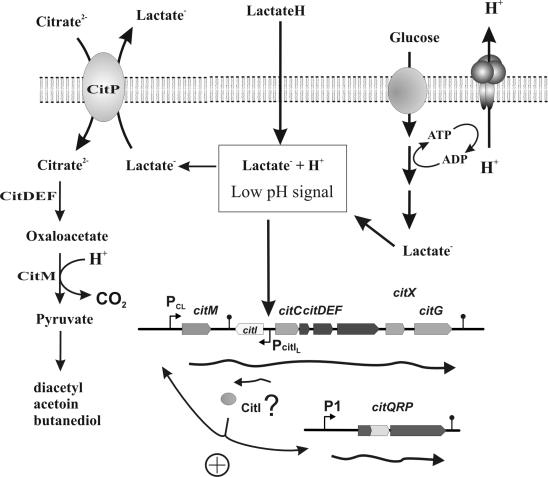

The scheme shown in Fig. 8 represents the contribution of the citrate fermentation to pH homeostasis in L. lactis. This bacterium produces lactic acid during glucose fermentation, implying that these cells are normally exposed to acid stress. At low pH, lactic acid (a weak organic acid) is not charged and can easily pass through the cell membrane in the protonated form. Inside the cell, it dissociates to the lactate1− form, producing a strong stress to the cell. As described here, when the external pH decreases to 5.0, lactococcal cells growing in M17G are able to sense the acidic stimulus and trigger the coordinated expression of the operons controlled by the P1 and Pcit promoters (Fig. 7). In the presence of citrate, the plasmid-encoded CitP permease is responsible for the specific removal of lactate from the cytosol (through the CitP citrateH2−/lactate1− antiport) (12). Cytoplasmic (chromosomally encoded) components of the citrate fermentation pathway then contribute to pH homeostasis, consuming scalar protons and generating a ΔpH (17). The pyruvate produced for the citrate fermentation is used for the production of less acidic compounds such as diacetyl and acetoin (Fig. 7). In this way L. lactis can survive at low pH during cometabolism of glucose and citrate. Thus, we propose that the pH-controlled expression of proteins required for the exchange of citrate for lactate coordinated with decarboxylation of citrate constitutes an important mechanism for acidic stress resistance in L. lactis.

FIG. 8.

Response of the cit operons to acidic stress and its contribution to pH homeostasis in L. lactis CRL264. The fermentation of glucose results in accumulation of lactic acid and acidification of the medium. Under these conditions, P1 and Pcit are activated, resulting in increased synthesis of CitP and the citrate lyase complex. The CitP transporter actively and specifically removes lactate from the cytoplasm, relieving the stress imposed by this weak acid. In addition, the increased metabolization of citrate contributes to alkalinization of the cytoplasm by enhancing the proton consumption. The regulator protein CitI could be involved in the regulation of both cit operons of L. lactis CRL264.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans Israelsen for generously providing pAK80, Mónica Arévalo and Alicia Bruzzone for technical assistance, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from Fundación Antorchas (Argentina) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina) (contract no. 01-09596-B and QLK12002-2388). M.G.M. and P.D.S. are fellows of CONICET (Argentina), and C.M. and D.D.M. are Career Investigators from the same institution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araya, T., N. Ishibashi, S. Shimamura, K. Tanaka, and H. Takahashi. 1993. Genetic and molecular analysis of the rpoD gene from Lactococcus lactis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekal-Si Ali, S., C. Diviès, and H. Prévost. 1999. Genetic organization of the citCDEF locus and identification of mae and clyR genes from Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J. Bacteriol. 181:4411-4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bott, M. 1997. Anaerobic citrate metabolism and its regulation in enterobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 167:78-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casiano-Colon, A., and R. E. Marquis. 1988. Role of the arginine deiminase system in protecting oral bacteria and an enzymatic basis for acid tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1318-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dornan, S., and M. A. Collins. 1990. High efficiency electroporation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis LM0230 with plasmid pGB301. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 11:62-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Quintáns, N., C. Magni, D. de Mendoza, and P. López. 1998. The citrate transport system of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis is induced by acid stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:850-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugenholtz, J. 1993. Citrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:165-178. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israelsen, H., S. M. Madsen, A. Vrang, E. B. Hansen, and E. Johansen. 1995. Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector, pAK80. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2540-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi, H., T. Suzuki, N. Kinoshita, and T. Unemoto. 1984. Amplification of the Streptococcus faecalis proton-translocating ATPase by a decrease in cytoplasmic pH. J. Bacteriol. 158:1157-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koebmann, B. J., D. Nilsson, O. P. Kuipers, and P. R. Jensen. 2000. The membrane-bound H+-ATPase complex is essential for growth of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4738-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez de Felipe, F., C. Magni, D. de Mendoza, and P. Lopez. 1995. Citrate utilization gene cluster of the Lactococcus lactis biovar diacetylactis: organization and regulation of expression. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:590-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lütgens, M., and G. Gottschalk. 1980. Why a co-substrate is required for anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli on citrate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magni, C., F. López de Felipe, F. Sesma, P. López, and D. de Mendoza. 1994. Citrate transport in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis. Expression of the citrate permease P. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 118:75-82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magni, C., F. L. de Felipe, P. López, and D. de Mendoza. 1996. Characterization of an insertion-like element identified in plasmid pCIT264 from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 136:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magni, C., D. de Mendoza, W. N. Konings, and J. Lolkema. 1999. Mechanism of citrate metabolism in Lactococcus lactis: resistance against lactate toxicity at low pH. J. Bacteriol. 181:1451-1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marquis, R. E., G. R. Bender, D. R. Murray, and A. Wong. 1987. Arginine deiminase system and bacterial adaptation to acid environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:198-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martín, M., M. A. Corrales, D. de Mendoza, P. López, and Ch. Magni. 1999. Cloning and molecular characterization of the citrate utilization citMCDEFGRP cluster of Leuconostoc paramesenteroides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martín, M., C. Magni, P. López, and D. de Mendoza. 2000. Transcriptional control of the citrate-inducible citMCDEFGRP operon, encoding genes involved in citrate fermentation in Leuconostoc paramesenteroides. J. Bacteriol. 182:3904-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Sullivan, D. J., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. Rapid mini-prep isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from Lactococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2730-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pos, K. M., P. Dimroth, and M. Bott. 1998. The Escherichia coli citrate carrier CitT: a member of the novel eubacterial transporter family related to the 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator from spinach chloroplasts. J. Bacteriol. 180:4160-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raya, R., J. Bardowski, P. S. Andersen, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Chopin. 1998. Multiple transcriptional control of the Lactococcus lactis trp operon. J. Bacteriol. 180:3174-3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Sanders, J. W., K. Leenhouts, J. Burghoorn, J. R. Brands, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1998. A chloride-inducible acid resistance mechanism in Lactococcus lactis and its regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider, K., C. N. Kastner, M. Meyer, M. Wessel, P. Dimroth, and M. Bott. 2002. Identification of a gene cluster in Klebsiella pneumoniae which includes citX, a gene required for biosynthesis of the citrate lyase prosthetic group. J. Bacteriol. 184:2439-2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sesma, F., D. Gardiol, A. P. Ruiz Holgado, and D. de Mendoza. 1990. Cloning of the citrate permease gene of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis and expression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2099-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuker, M., and P. Stiegler. 1981. Optimal computer folding of large RNA sequences using thermodynamics and auxiliary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 9:133-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]