Abstract

Hydrogenovibrio marinus strain MH-110, an obligately lithoautotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, fixes CO2 by the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle. Strain MH-110 possesses three different sets of genes for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO): CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2, which belong to form I (L8S8), and CbbM, which belongs to form II (Lx). In this paper, we report that the genes for CbbLS-1 (cbbLS-1) and CbbM (cbbM) are both followed by the cbbQO genes and preceded by the cbbR genes encoding LysR-type regulators. In contrast, the gene for CbbLS-2 (cbbLS-2) is followed by genes encoding carboxysome shell peptides. We also characterized the three RubisCOs in vivo by examining their expression profiles in environments with different CO2 availabilities. Immunoblot analyses revealed that when strain MH-110 was cultivated in 15% CO2, only the form II RubisCO, CbbM, was expressed. When strain MH-110 was cultivated in 2% CO2, CbbLS-1 was expressed in addition to CbbM. In the 0.15% CO2 culture, the expression of CbbM decreased and that of CbbLS-1 disappeared, and CbbLS-2 was expressed. In the atmospheric CO2 concentration of approximately 0.03%, all three RubisCOs were expressed. Transcriptional analyses of mRNA by reverse transcription-PCR showed that the regulation was at the transcriptional level. Electron microscopic observation of MH-110 cells revealed the formation of carboxysomes in the 0.15% CO2 concentration. The results obtained here indicate that strain MH-110 adapts well to various CO2 concentrations by using different types of RubisCO enzymes.

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO;EC 4.1.1.39) is a key enzyme in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle. RubisCO for the CBB cycle is typically categorized into two forms. Form I RubisCO, the most common form, consists of eight large and eight small subunits in a hexadecameric (L8S8) structure. This form is widely distributed in CO2-fixing organisms, including all higher plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and many autotrophic bacteria. Form II RubisCO, on the other hand, consists of only large subunits (Lx), the number of which differs among organisms. Although this form, first found in Rhodospirillum rubrum (31, 42), is more widespread among species than was originally thought, its existence is limited to autotrophic bacteria. In addition to these traditional form I and form II enzymes, two novel types, form III and form IV RubisCO, have been revealed by the complete genome sequences of some archaea and bacteria (1, 12, 17, 47). Even though these two forms have not been shown to be a part of the CBB cycle, form III and form IV RubisCOs are fairly well established now.

RubisCO for the CBB cycle catalyzes two different reactions: CO2 fixation, in which CO2 interacts with enzyme-bound ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) to produce 2 molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA), and O2 fixation, in which O2 interacts with enzyme-bound RuBP to produce 1 molecule each of PGA and 2-phosphoglycolate (PG). A RubisCO enzyme's efficiency is usually measured by the specificity factor (τ), which is the ratio of the rate constants for both CO2 and O2 fixation (29). The higher a RubisCO's τ value is, the better the RubisCO can discern CO2 from O2. This endows it with highly efficient CO2 fixation and thus allows it to adjust to a lower CO2 concentration. The τ value is generally over 80 for form I RubisCO in higher plants, between 25 and 75 for form I RubisCO in bacteria, and under 20 for form II RubisCO (24, 40).

Some bacteria have been found to possess more than one set of RubisCO genes. Ralstonia eutropha (26) and Chromatium vinosum (45) have two sets of genes that encode form I enzymes, while Halothiobacillus neapolitanus (formerly Thiobacillus neapolitanus) (38), Thiomonas intermedia (formerly Thiobacillus intermedius) (41), Thiobacillus denitrificans (11), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (14), and Rhodobacter capsulatus (15, 35) have genes for both form I and form II enzymes. Moreover, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (formerly Thiobacillus ferrooxidans) (23) and Hydrogenovibrio marinus (34, 48) have three different sets of RubisCO genes, two of which encode form I enzymes while the third encodes a form II enzyme.

Previous studies indicated that the expression of both forms of RubisCO is correlated with CO2 concentration. In R. sphaeroides, synthesis of both form I and form II RubisCOs was augmented when the bacterium was moved from heterotrophic (malate as a carbon source) to autotrophic (H2 with 1.5% CO2) growth conditions. But the promotion of form I RubisCO synthesis is higher than that of form II. Probably the form I enzyme must be expressed in a low-CO2 concentration to support growth (25). In H. neapolitanus, both form I and form II RubisCOs were synthesized when the organism was cultured in air supplemented with 5% CO2, but when it was cultured in air alone, the expression of form I RubisCO increased and that of form II decreased (4). The disruption of a form I RubisCO gene results in the promotion of form II RubisCO gene expression, but the mutant is unable to grow in atmospheric CO2 concentrations (4).

In autotrophic bacteria, a RubisCO gene, whether it encodes a form I or a form II enzyme, is generally clustered with CBB cycle-related genes, such as cbbP, the gene for phosphoribulokinase, and cbbF, the gene for fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (13, 22, 30). In some cases, the RubisCO genes are clustered with the genes for carboxysome shell peptides. A carboxysome is a polyhedral organelle in which RubisCOs are sequestered, and it plays an important role in CO2 fixation (37, 39). This gene organization has been examined in thiobacilli (5). In many cases, the regulatory gene cbbR is located upstream of the RubisCO gene in the opposite orientation (40). cbbR encodes a LysR-type transcriptional regulator that induces the transcription of the RubisCO gene and other cbb genes.

H. marinus strain MH-110 is an obligately lithoautotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a marine environment (32, 33). As stated above, this organism possesses three different sets of RubisCO genes: cbbLS-1 and cbbLS-2 encode the form I enzymes CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2, respectively, and cbbM encodes the form II enzyme CbbM. Until now, CbbM was purified from H. marinus, while CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2 were purified by using the heterologous expression system of E. coli (6, 21). It has been revealed that each of the three RubisCOs has different properties in vitro. The specificity factors (τ) of CbbLS-1, CbbLS-2, and CbbM were determined to be 26.6, 33.1, and 14.8, respectively, suggesting that RubisCOs are adapted to different CO2 concentrations (21, 49). The structural genes of the three RubisCOs were cloned, and their nucleotide sequences were determined (34, 48). The cbbQ-type gene, which is similar to the nirQ/norQ gene of denitrifying bacteria, was found downstream of cbbM (18). However, the complete structure of each of the three RubisCO gene clusters remains to be investigated. In this study, we clarified the organization of the cbbLS-1, cbbLS-2, and cbbM gene clusters in strain MH-110 and characterized the three RubisCOs in vivo by examining their expression profiles in different CO2 concentrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

E. coli strains DH5 and JM109 were used as hosts for the Charomid 9-36 (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan) and pUC119 vectors, respectively. E. coli strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C with 50 μg of ampicillin/ml. H. marinus was cultivated under atmospheric pressure consisting of H2, O2, and CO2 (75:15:10, vol/vol/vol) at 37°C in an inorganic medium as described previously (33). For large-scale cultures, 50 ml of precultivated cells was inoculated into a 1-liter fermentor (BMJ-1; Able, Tokyo, Japan) containing 0.5 liters of medium and was cultivated at 37°C with a constant supply (gas flux, 0.5 liters/min) of a gas mixture consisting of either (i) 70% H2, 15% O2, and 15% CO2, (ii) 83% H2, 15% O2, and 2% CO2, (iii) 85% H2, 15% O2, and 0.15% CO2, or (iv) 20% H2 and 80% air (equivalent to 0.03% CO2).

Cloning and DNA sequencing.

Standard protocols were employed for DNA manipulation and cloning (36). Restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Bio (Kyoto, Japan) and Toyobo (Osaka, Japan). For Southern hybridizations, digested DNA was separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto a Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The DNA probes were nonradioactively labeled with digoxigenin. A 618-bp SphI-HindIII fragment of plasmid pJN1 (34), a 455-bp KpnI-EcoRI fragment of pJS1 (34), and a 1,375-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pYAH508 (18) were used as probes in the cloning of the downstream regions of cbbLS-1, cbbLS-2, and cbbM, respectively. A 775-bp HindIII-BamHI fragment of pCM1 (Fig. 1) was used as a probe for the cloning of the region farther downstream of cbbM. To clone the upstream regions, 776-, 893-, and 853-bp PCR fragments were used for the probes. The nucleotide sequences for PCR amplification were as follows: 5′-GCTGGATCCTACATTGGTTTTGCC-3′ and 5′-TAAGGGAATTCTAATAACAAAATCACC-3′ for cbbLS-1, 5′-CTATATCAAGGATCCAGATC-3′ and 5′-CGTTAACCACATAAGCTTCTTC-3′ for cbbLS-2, and 5′-CGAATTGGGATCCTAACTTACCC-3′ and 5′-GAAGTCATAACAAGCTTTCGCG-3′ for cbbM.

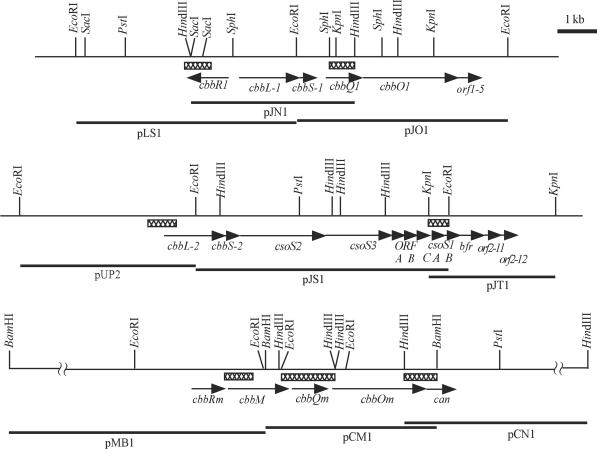

FIG. 1.

Physical maps of the RubisCO gene clusters of H. marinus. cbbL and cbbS encode large and small subunits of form I RubisCO, respectively. cbbM encodes form II RubisCO. cbbR encodes a LysR-type transcriptional regulator. cbbQ and cbbO encode proteins involved in posttranslational activation of RubisCO. cso genes encode carboxysomal proteins. bfr encodes bacterioferritin. can encodes carbonic anhydrase. Crosshatched boxes indicate positions of probes used for cloning.

DNA-DNA hybrids on the membranes were detected by a staining reaction involving nitroblue tetrazolium, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, and alkaline phosphate conjugated to anti-digoxigenin Fab fragments (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Based on the Southern blot analyses, gene libraries were constructed. Positive clones were identified by colony hybridizations with the same probes used in the Southern hybridizations. pLS1 and pJO1 carry a 5.4- and a 5.2-kb EcoRI fragment upstream and downstream of cbbLS-1, respectively. pUP2 and pJT1 carry a 4.3-kb EcoRI fragment and a 3.1-kb KpnI fragment upstream and downstream of cbbLS-2, respectively. pMB1 and pCM1 carry a 7.8- and a 4.2-kb BamHI fragment upstream and downstream of cbbM, respectively. pCN1 carries a 6.0-kb HindIII fragment farther downstream of pCM1 (Fig. 1). A Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Japan, Applied Biosystems Division) was used for dideoxy chain-termination, and an ABI PRISM model 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) was used for DNA sequence determination. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Sawady (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of CFE.

H. marinus cells cultivated in different CO2 concentrations were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in BEMD buffer (50 mM Bicine, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [pH 7.8]). The cells were disrupted by passing the suspension twice through a French pressure cell at 110 MPa. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g and 4°C for 1 h, and the supernatant was used as cell extracts (CFE). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

PAGE and Western blot analysis.

CFE were separated by 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-15% PAGE). The proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Sequi-Blot PVDF membrane; Bio-Rad) in a Trans-Blot electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad). Western blotting was performed using anti-RubisCO antibodies and, as a secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, blotting grade, affinity-purified goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H+L) (Bio-Rad). The desired proteins were detected with an HRP-1000 immunostaining kit (Konica, Tokyo, Japan). Antibodies that could specifically distinguish between CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2 were raised against synthetic oligopeptides that have sequences specific to small subunits of CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2, respectively. The sequences of oligopeptides are PSRLSDPTSRKAC for CbbS-1 and EFTADEIYDQIVC for CbbS-2. The oligopeptides and antisera were prepared by Takara Bio. The anti-CbbM antibody was generated against the purified enzyme from strain MH-110.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from bacterial cells by using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene), which is based on the acid guanidine thiocyanate phenol-chloroform extraction method. The reaction mixture for reverse transcription (RT) was prepared on a half scale of the two-step RT-PCR protocol by using the mRNA Selective PCR kit (version 1.1; Takara Bio). Two micrograms of total RNA was used for the RT reaction, which was conducted at 50°C for 15 min using synthetic oligonucleotide primers. Primers (with sequences in parentheses) were as follows: L12-RT (5′-CTGGCATGTGCCATACGTGG-3′) for cbbLS-1 and cbbLS-2 and M-RT (5′-AGTAGGTTTCATGCCGTACC-3′) for cbbM.

To amplify the cDNA produced from RNA by the RT reaction, PCR was performed according to the protocol. As a template, 5 μl of the RT product was used. The forward and reverse primers for RubisCO genes (with nucleotide sequences in parentheses) were as follows: L1-F (5′-TGGATGCCAGAGTATGAGCC-3′) and L1-R (5′-GTCACGCATGATGTCGATCC-3′) for cbbLS-1; L2-F (5′-GACACCAGACTACACTCCTC-3′) and L2-R (5′-CGAAACCTAGCGTAGAAGCG-3′) for cbbLS-2; and M-F (5′-TTCACTCGTGGTGTTGATGC-3′) and M-R (5′-CGAGCAAGCTTCATGTAGCA-3′) for cbbM.

The PCR condition was 30 cycles of amplification, each cycle consisting of a denaturing step for 1 min at 85°C, an annealing step for 1 min at 45°C, and an extension step for 2 min at 72°C. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. After being stained with ethidium bromide, the gel was exposed to a UV illuminator.

Electron microscopy.

Cells were prefixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h at room temperature. After dehydration in an ethanol series and then in propylene oxide, the cells were embedded into Quetol 812 epoxy resin (Nisshin EM, Tokyo, Japan), and the resin was polymerized at 55°C overnight. Blocks were cut into ultrathin sections with a diamond knife on a microtome. Microscopic observation was performed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM-1010; JEOL Hightech Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to the DDBJ, EMBL, and NCBI nucleotide sequence databases under accession numbers AB122069, AB122070, and AB122071.

RESULTS

Organization of the RubisCO gene clusters.

The genes for RubisCO are usually clustered with the genes for other CBB cycle enzymes in autotrophic bacteria (27). In the case of strain MH-110, cbbQm, which was identified downstream of cbbM, had been the only gene found in the flanking region of the three RubisCO genes (18). To clarify the organization of the RubisCO gene clusters, we cloned the upstream and downstream regions of each RubisCO gene and determined the nucleotide sequences of the cloned fragments (Fig. 1). cbbLS-1 is followed by the genes designated cbbQ1, cbbO1, and orf1-5. Translated sequences of cbbQ1 and cbbO1 have 74 and 38% amino acid identity with those of cbbQ and cbbO of Hydrogenophilus thermoluteolus TH-1, respectively. The cbbQ-type genes encode putative ATP-binding proteins and are similar to the norQ/nirQ-type genes (7, 50). The cbbO genes are similar to the norD genes (20, 22). The norQ/nirQ and norD genes are located in the vicinity of the genes for cytochrome bc-type nitric oxide reductase of denitrification bacteria. These genes are required for the expression of functional nitric oxide reductase or anaerobic growth by denitrification (7, 19). Preliminary experiments suggested that the cbbQ and cbbO gene products are involved in the posttranslational activation or conformational change of RubisCO, but the physiological functions of these gene products are still unclear (18, 20). orf1-5 encodes a protein of 178 amino acids that is not homologous to any protein in the protein databases. As with the RubisCO gene clusters of other autotrophic bacteria, the cbbR-type gene, encoding a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, is located upstream of cbbLS-1 in the opposite direction and is designated cbbR1. cbbLS-2 is followed by csoS2, csoS3, orfA and orfB, and csoS1C, csoS1A, and csoS1B, each of which encodes a carboxysome shell peptide. Translated sequences of the genes are 26, 44, 74, 49, 92, 88, and 90% identical to those of the corresponding genes of H. neapolitanus (2, 3, 10). These genes are followed by bfr, which encodes a putative bacterioferritin, and two unknown open reading frames (ORFs), namely, orf2-11 and orf2-12. cbbLS-2 and the genes that follow it are assembled in an operon-like structure, suggesting that carboxysomes are formed under the conditions under which CbbLS-2 is expressed. The cbbR-type gene was not found in the upstream region of cbbLS-2 (data not shown). In the downstream region of cbbM, a cbbO-type gene, which is designated cbbOm, is newly located downstream of cbbQm, thus revealing the existence of two sets of cbbQO genes in strain MH-110. Translated sequences of cbbQm and cbbOm have 69 and 32% identity with those of cbbQ1 and cbbO1, respectively. The can gene, encoding carbonic anhydrase (EC 4.2.1.1), was found downstream of cbbOm. Carbonic anhydrase catalyzes the hydration-dehydration of CO2-HCO3− and has been shown to be essential for the growth of R. eutropha at ambient CO2 concentrations (28), but its role in strain MH-110 remains to be investigated. Another cbbR gene, designated cbbRm, was found in the upstream region. This gene lies in the same orientation with cbbM, in contrast to cbbR1, which is located in the opposite orientation to cbbLS-1. CbbRm shares 32% identity with CbbR1. The other genes found in the seven cloned fragments are not likely to be involved in CO2 fixation (data not shown).

Effect of CO2 concentration on the growth of H. marinus.

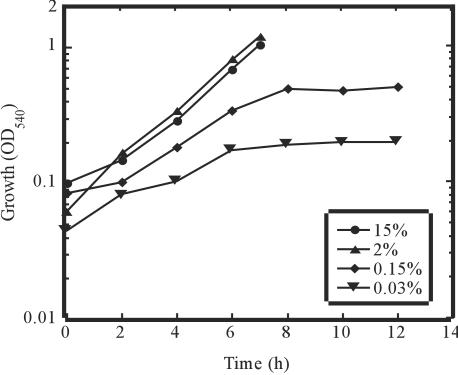

In order to determine the effect of CO2 availability on cell growth, strain MH-110 was cultivated in different CO2 concentrations: 15, 2, 0.15, and 0.03% (Fig. 2). At CO2 concentrations of 15 and 2%, strain MH-110 showed short doubling times, 2.2 and 1.9 h, respectively. This indicates an adequate CO2 supply in the medium. At a CO2 concentration of 0.15%, however, the doubling time increased to 5.1 h, making CO2 availability the limiting factor. Strain MH-110 was able to grow even at a CO2 concentration of 0.03% (in the 20% H2-80% air mixture), but the doubling time increased further, to 11.0 h, and the optical density at 540 nm reached about 0.2 at maximum.

FIG. 2.

Growth of H. marinus in a CO2 concentration of 15, 2, 0.15, or 0.03%. Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 540 nm.

Effect of CO2 concentration on expression of RubisCO enzymes.

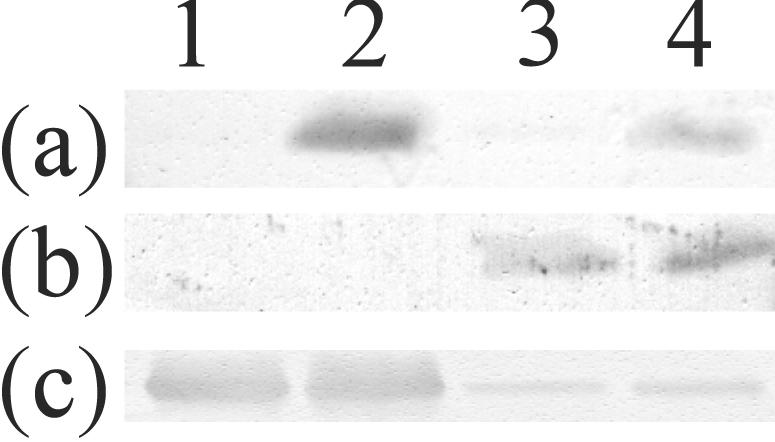

The expression patterns of the three RubisCO enzymes at the different CO2 concentrations were determined by an immunological method. Immunoblotting was performed with three different antibodies that recognize CbbLS-1, CbbLS-2, and CbbM, respectively. Since CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2 have high homology, anti-CbbLS-1 and anti-CbbLS-2 antibodies were raised against synthetic oligopeptides that have unique sequences designed from N-terminal amino acid sequences of CbbS-1 and CbbS-2, respectively. The prepared antibodies were tested for cross-reactivity between CbbLS-1 and CbbLS-2 by using recombinant enzymes expressed in E. coli cells, and no cross-reactivity was observed (data not shown). An anti-form II RubisCO antibody was raised against purified form II RubisCO from H. marinus (Fig. 3). When the bacterium was cultivated at a CO2 concentration of 15%, only the form II RubisCO, CbbM, was expressed. When cultivated at a CO2 concentration of 2%, CbbLS-1 and CbbM were expressed. In the 0.15% CO2 culture, CbbLS-2 and CbbM were expressed. In the 0.03% CO2 culture, all three RubisCOs were expressed. These results indicate different properties of the three RubisCOs in vivo.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analyses of CbbLS-1, CbbLS-2, and CbbM RubisCOs. CFE (3 μg) were resolved on an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. An anti-CbbLS-1 oligopeptide antibody (a), an anti-CbbLS-2 oligopeptide antibody (b), and an anti-form II RubisCO antibody raised against CbbM from H. marinus (c) were used. CFE were prepared from 15% (lane 1), 2% (lane 2), 0.15% (lane 3), or 0.03% (lane 4) CO2 cultures.

Effect of CO2 concentration on transcription of the RubisCO genes.

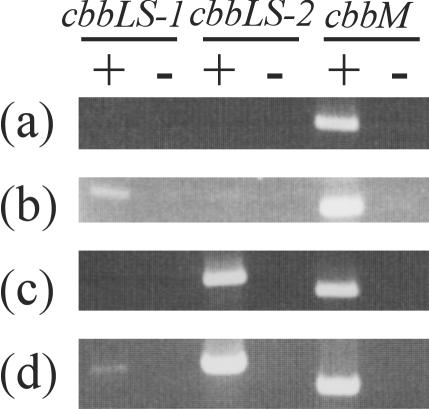

The expression pattern of RubisCO at the transcriptional level was examined by RT-PCR. Oligonucleotide primer sets constructed for PCR amplification of each RubisCO were shown not to hybridize to other RubisCO genes (data not shown). The RT-PCR results showed that only cbbM was expressed at a CO2 concentration of 15%, cbbLS-1 and cbbM were expressed at 2% CO2, cbbLS-2 and cbbM were expressed at 0.15% CO2, and all three genes were expressed at 0.03% CO2 (Fig. 4). These results were consistent with those of the immunological analyses, indicating that the expression of the three RubisCOs was regulated at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 4.

Analyses by RT-PCR of expression of the three RubisCO genes. RNA was isolated from cells grown in a CO2 concentration of 15% (a), 2% (b), 0.15% (c), or 0.03% (d). +, RT was carried out before PCR; −, PCR without the RT reaction.

Formation of carboxysomes at low CO2 concentrations.

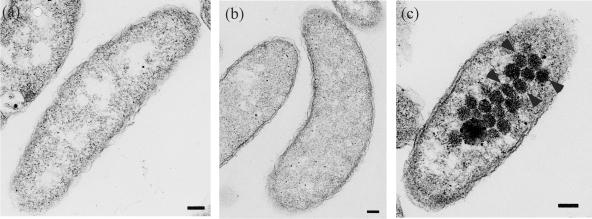

Cells that were cultivated at CO2 concentrations of 15, 2, or 0.15% were harvested for electron microscopic observations (Fig. 5). Many polyhedral particles approximately 100 nm long, showing the typical shape and approximate size of carboxysomes, were observed in cells grown at a CO2 concentration of 0.15%. They were scarcely found in cells grown at a CO2 concentration of 15 or 2%.

FIG. 5.

Electron micrographs of H. marinus grown in a CO2 concentration of 15% (a), 2% (b), or 0.15% (c). Arrowheads indicate carboxysomes. Bar, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we determined the gene organizations of the three RubisCO gene clusters of H. marinus strain MH-110. We found two sets of the cbbQO and cbbR genes in the cbbLS-1 and cbbM gene clusters, the genes for carboxysome shell peptides in the cbbLS-2 gene cluster, and the carbonic anhydrase gene in the cbbM gene cluster. Other genes found in the cloned fragments were not likely to be involved in CO2 fixation. It is worth noting that despite the high similarity of nucleotide sequences between cbbLS-1 and cbbLS-2 (34), the organization of the cbbLS-1 gene cluster is totally different from that of the cbbLS-2 gene cluster; cbbLS-1 clustered with the cbbR and cbbQO genes, and cbbLS-2 clustered with carboxysome genes in an operon-like structure. It is also interesting that cbbLS-1 and cbbM, which encode different forms of RubisCO, have similar gene clusters, with the cbbR gene upstream and the cbbQO genes downstream. This pattern of distinct RubisCO gene clusters for cbbLS-1 versus cbbLS-2 and similar clusters for cbbLS-1 and cbbM may not be the result of simple gene duplication in the ancestor of H. marinus, as suggested previously (34), or of lateral gene transfer, as proposed in the case of A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 (23). Rather, it appears that complicated phenomena of gene duplication, lateral gene transfer, and reorganization have occurred during evolution. One possible interpretation of such gene clusters is that cbbLS-1 was reproduced by gene duplication of cbbLS-2, which had been introduced by lateral gene transfer, and the gene reorganization was followed with the cbbR and cbbQO genes of the cbbM cluster, which the ancestor of strain MH-110 might have originally possessed.

RubisCO and other CBB cycle-related genes are usually clustered in various chemo- and photoautotrophic bacteria (27). Strain MH-110 is unique in that the genes for the other CBB cycle enzymes are not clustered with the RubisCO genes. This is probably related to the fact that strain MH-110 is an obligatory autotroph. In facultative autotrophs, the CBB cycle enzymes must be uniformly regulated by the availability of suitable carbon and energy sources; clustering of the genes as a single operon or a few operons might be advantageous for uniform regulation. On the other hand, the CBB cycle is constitutively active, and uniform regulation is not necessary in obligatory autotrophs. This is probably the reason why the genes for the other CBB enzymes are not cotranscribed with the RubisCO genes as an operon in strain MH-110. Another probable reason is that, because the transcription of each of the three RubisCO genes varies according to the CO2 concentration as mentioned below, cotranscription of the other cbb genes with one of the three RubisCO genes might be unsuitable for keeping the balance of total CBB cycle activity at various CO2 concentrations. In either case, analysis of the other cbb genes will be necessary in order to understand the regulation of the whole CBB cycle in strain MH-110.

Also, the three RubisCOs were characterized by examining their expression in vivo in environments with different CO2 availabilities. It has been suggested previously that, in a microbe which has genes for both form I and II RubisCOs, form II and form I enzymes are predominantly expressed at high and low CO2 concentrations, respectively (25, 40). Nevertheless, this hypothesis has not been tested in detail. This is the first report that three RubisCO enzymes of H. marinus are differentially expressed depending on the CO2 concentration, and it was revealed that expression was complexly regulated by the CO2 concentration. The expression pattern was in good accordance with the specificity factor (τ) of each RubisCO. The τ value, determined by calculating the ratio of the rate constants for both carboxylase and oxygenase reactions, indicates each RubisCO's efficiency at distinguishing between CO2 and O2 (29). A high τ value for RubisCO means that the enzyme can selectively assimilate CO2 in spite of the existence of O2, and thus it is better adjusted to a lower CO2 concentration. Under the CO2-rich condition (15%), only CbbM, which has the lowest τ value (14.8) of the three RubisCOs, was expressed in strain MH-110. Decreasing the CO2 concentration to 2% triggered the expression of CbbLS-1, which has the middle τ value (26.6) of the three. When the CO2 concentration was decreased from 2 to 0.15%, CbbLS-1 disappeared, and CbbLS-2, which has the highest τ value (33.1), took its place. Moreover, the amount of CbbM decreased at that concentration. At the extremely low CO2 concentration (0.03%), CbbLS-1 reappeared, and thus all three RubisCOs were expressed. Electron microscopic observation showed the formation of carboxysomes at the 0.15% CO2 concentration. This was the concentration at which CbbLS-2 was expressed, suggesting that the genes for CbbLS-2 and carboxysome shell peptides in the cbbLS-2 gene cluster are transcribed as an operon. CbbLS-2 is probably sequestered in carboxysomes that help the enzyme fix CO2 at low CO2 concentrations, as in the case of cyanobacteria and thiobacilli such as H. neapolitanus (37).

CbbM and CbbLS-2 turned out to be subjected to one-stage regulation by CO2. CbbM was expressed in large quantities at high CO2 concentrations, and in diminished quantities at low CO2 concentrations. The threshold was somewhere between 2 and 0.15%. CbbLS-2, on the other hand, was not expressed at high CO2 concentrations but rather was induced at low CO2 concentrations. The threshold was also somewhere between 2 and 0.15%. This fact may suggest that this organism may undergo a dynamic change of gene expression when CO2 is downshifted from 2 to 0.15%. It has been reported recently for the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 that a CO2 downshift induced changes in global gene expression and a dramatic up-regulation of genes involved in inducible CO2 and HCO3− uptake systems (46). Similar changes may occur in strain MH-110 as well. The regulation of CbbLS-1 was more complicated. It was not expressed at a CO2 concentration of 15 or 0.15% but was expressed at 2 and 0.03% CO2, suggesting that the external CO2 concentration alone did not directly regulate expression. Rather, the cytoplasmic CO2 concentration or some kinds of CBB cycle intermediates may affect the expression of CbbLS-1. It seems that cbbLS-1 is expressed when CO2 fixation activity by CbbLS-2 and/or CbbM is not enough for cell growth. To confirm the role of cbbLS-1 and to further examine the regulation of expression of the three RubisCO genes, it is necessary to knock out each RubisCO gene. A method for constructing isogenic mutants is now under way.

The RT-PCR analyses showed that the expression of the three RubisCOs was regulated at the transcriptional level. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator, cbbR, is encoded upstream of both the cbbLS-1 and cbbM genes, as in other autotrophic bacteria (40), but not upstream of cbbLS-2. Neither CbbR1 nor CbbRm is likely to sense a CO2 molecule directly, since the signal molecule for CbbR has been reported to be NADPH in Xanthobacter flavus and H. thermoluteolus, or phosphoenolpyruvate in R. eutropha (16, 43, 44). In the case of R. sphaeroides, which has two distinct cbb gene clusters, cbbI and cbbII, CbbR is not encoded in the cbbII gene cluster, but the CbbR encoded in the cbbI gene cluster regulates both of the cbb clusters (8). In addition to CbbR and RegA, the latter of which is the response regulator of the regA-regB two-component regulatory system, two unidentified proteins bind to the promoter region of cbbII in this bacterium (9). It is not certain whether CbbR1 and CbbRm regulate the cbbLS-2 gene cluster in strain MH-110. However, the CO2 concentration-responsive regulation of the three RubisCO genes should be interrelated by the action of multiple regulators, including CbbR1 and CbbRm. Future work will focus on clarification of the role of the two CbbR regulators and identification of the other regulators that control the expression of the RubisCO genes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashida, H., Y. Saito, C. Kojima, K. Kobayashi, N. Ogasawara, and A. Yokota. 2003. A functional link between RuBisCO-like protein of Bacillus and photosynthetic RuBisCO. Science 302:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, S. H., S. C. Lorbach, M. Rodriguez-Buey, D. S. Williams, H. C. Aldrich, and J. M. Shively. 1999. The correlation of the gene csoS2 of the carboxysome operon with two polypeptides of the carboxysome in Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Arch. Microbiol. 172:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, S. H., D. S. Williams, H. C. Aldrich, A. C. Gambrell, and J. M. Shively. 2000. Identification and localization of the carboxysome peptide Csos3 and its corresponding gene in Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Arch. Microbiol. 173:278-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, S. H., S. Jin, H. C. Aldrich, G. T. Howard, and J. M. Shively. 1998. Insertion mutation of the form I cbbL gene encoding ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) in Thiobacillus neapolitanus results in expression of form II RuBisCO, loss of carboxysomes, and an increased CO2 requirement for growth. J. Bacteriol. 180:4133-4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon, G. C., S. H. Baker, F. Soyer, D. R. Johnson, C. E. Bradburne, J. L. Mehlman, P. S. Davies, Q. L. Jiang, S. Heinhorst, and J. M. Shively. 2003. Organization of carboxysome genes in the thiobacilli. Curr. Microbiol. 46:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung, S. Y., T. Yaguchi, H. Nishihara, Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1993. Purification of form L2 RubisCO from a marine obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenovibrio marinus strain MH-110. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 109:49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer, A. P., J. van der Oost, W. N. Reijnders, H. V. Westerhoff, A. H. Stouthamer, and R. J. van Spanning. 1996. Mutational analysis of the nor gene cluster which encodes nitric-oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur. J. Biochem. 242:592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubbs, J. M., T. H. Bird, C. E. Bauer, and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Interaction of CbbR and RegA transcription regulators with the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cbbI promoter-operator region. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19224-19230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubbs, J. M., and F. R. Tabita. 2003. Interactions of the cbbII promoter-operator region with CbbR and RegA (PrrA) regulators indicate distinct mechanisms to control expression of the two cbb operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16443-16450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.English, R. S., S. C. Lorbach, X. Qin, and J. M. Shively. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a carboxysome shell gene from Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Mol. Microbiol. 12:647-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English, R. S., C. A. Williams, S. C. Lorbach, and J. M. Shively. 1992. Two forms of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from Thiobacillus denitrificans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 94:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezaki, S., N. Maeda, T. Kishimoto, H. Atomi, and T. Imanaka. 1999. Presence of a structurally novel type ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5078-5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson, J. L., D. L. Falcone, and F. R. Tabita. 1991. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional analysis, and expression of genes encoded within the form I CO2 fixation operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 266:14646-14653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1977. Different molecular forms of d-ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 252:943-949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1977. Isolation and preliminary characterization of two forms of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 132:818-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzeszik, C., T. Jeffke, J. Schaferjohann, B. Kusian, and B. Bowien. 2000. Phosphoenolpyruvate is a signal metabolite in transcriptional control of the cbb CO2 fixation operons in Ralstonia eutropha. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:311-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson, T. E., and F. R. Tabita. 2001. A ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO)-like protein from Chlorobium tepidum that is involved with sulfur metabolism and the response to oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4397-4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi, N. R., H. Arai, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1999. The cbbQ genes, located downstream of the form I and form II RubisCO genes, affect the activity of both RubisCOs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi, N. R., H. Arai, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1998. The nirQ gene, which is required for denitrification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can activate the RubisCO from Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1381:347-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi, N. R., H. Arai, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1997. The novel genes, cbbQ and cbbO, located downstream from the RubisCO genes of Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila, affect the conformational states and activity of RubisCO. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 241:565-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi, N. R., A. Oguni, T. Yaguchi, S. Y. Chung, H. Nishihara, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1998. Different properties of gene products of three sets ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from a marine obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenovibrio marinus strain MH-110. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 85:150-155. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi, N. R., K. Terazono, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 2000. Structure of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase gene cluster from a thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenophilus thermoluteolus, and phylogeny of the fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase encoded by cbbA in the cluster. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinhorst, S., S. H. Baker, D. R. Johnson, P. S. Davies, G. C. Cannon, and J. M. Shively. 2002. Two copies of form I RuBisCO genes in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270. Curr. Microbiol. 45:115-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan, D. B., and W. L. Ogren. 1981. Species variation in the specificity of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Nature 291:513-515. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jouanneau, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1986. Independent regulation of synthesis of form I and form II ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 165:620-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusian, B., R. Bednarski, M. Husemann, and B. Bowien. 1995. Characterization of the dupulicate ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase genes and cbb promoters of Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 177:4442-4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusian, B., and B. Bowien. 1997. Organization and regulation of cbb CO2 assimilation genes in autotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:135-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusian, B., D. Sültemeyer, and B. Bowien. 2002. Carbonic anhydrase is essential for growth of Ralstonia eutropha at ambient CO2 concentrations. J. Bacteriol. 184:5018-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laing, W. A., W. L. Ogren, and R. H. Hageman. 1974. Regulation of soybean net photosynthetic CO2 fixation by the interaction of CO2, O2, and ribulose 1,5-diphosphate carboxylase. Plant Physiol. 54:678-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijer, W. G., A. C. Arnberg, H. G. Enequist, P. Terpstra, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Dijkhuizen. 1991. Identification and organization of carbon dioxide fixation genes in Xanthobacter flavus H4-14. Mol. Gen. Genet. 225:320-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nargang, F., L. McIntosh, and C. Somerville. 1984. Nucleotide sequence of the ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase gene from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 193:220-224. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishihara, H., Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1991. Hydrogenovibrio marinus gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine obligately chemolithoautotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:130-133. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishihara, H., Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1989. Isolation of an obligately chemolithoautotrophic, halophilic and aerobic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium from a marine environment. Arch. Microbiol. 152:39-43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishihara, H., T. Yaguchi, S. Y. Chung, K. Suzuki, M. Yanagi, K. Yamasato, T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1998. Phylogenetic position of an obligately chemoautotrophic, marine hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenovibiro marinus, on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences and two form I RubisCO gene sequences. Arch. Microbiol. 169:364-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paoli, G. C., N. S. Morgan, F. R. Tabita, and J. M. Shively. 1995. Expression of the cbbLcbbS and cbbM genes and distinct organization of the cbb Calvin cycle structural genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Arch. Microbiol. 164:396-405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Shively, J. M., F. Ball, D. H. Brown, and R. E. Saunders. 1973. Functional organelles in prokaryotes: polyhedral inclusions (carboxysomes) of Thiobacillus neapolitanus. Science 182:584-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shively, J. M., W. Devore, L. Stratford, L. Porter, L. Medlin, and S. E. Stevens. 1986. Molecular evolution of the large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 37:251-257. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shively, J. M., and R. S. English. 1991. The carboxysome, a prokaryotic organelle: a mini review. Can. J. Bot. 69:957-962. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shively, J. M., G. van Keulen, and W. G. Meijer. 1998. Something from almost nothing: carbon dioxide fixation in chemoautotrophs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:191-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoner, M. T., and J. M. Shively. 1993. Cloning and expression of the d-ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase form II gene from Thiobacillus intermedius in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 107:287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabita, F. R., and B. A. McFadden. 1974. d-Ribulose-1,5-diphosphate carboxylase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Biol. Chem. 249:3459-3464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terazono, K., N. R. Hayashi, and Y. Igarashi. 2001. CbbR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator from Hydrogenophilus thermoluteolus, binds two cbb promoter regions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Keulen, G., L. Girbal, E. R. E. van den Bergh, L. Dijkhuizen, and W. G. Meijer. 1998. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator CbbR controlling autotrophic CO2 fixation by Xanthobacter flavus is an NADPH sensor. J. Bacteriol. 180:1411-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viale, A. M., H. Kobayashi, and T. Akazawa. 1989. Expressed genes for plant-type ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in the photosynthetic bacterium Chromatium vinosum, which possesses two complete sets of the genes. J. Bacteriol. 171:2391-2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, H. L., B. L. Postier, and R. L. Burnap. 2004. Alternations in global patterns of gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 in response to inorganic carbon limitation and the inactivation of ndhR, a LysR family regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 279:5739-5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson, G. M. F., J. P. Yu, and F. R. Tabita. 1999. Unusual ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase of anoxic Archaea. J. Bacteriol. 181:1569-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yaguchi, T., S. Y. Chung, Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1994. Cloning and sequence of the L2 form of RubisCO from a marine obligately autotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenovibrio marinus strain MH-110. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 58:1733-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaguchi, T., A. Oguni, N. Ouchiyama, Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1996. A non-radioisotopic anion-exchange chromatographic method to measure the CO2/O2 specificity factor for ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 60:942-944. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yokoyama, K., N. R. Hayashi, H. Arai, S. Y. Chung, Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1995. Genes encoding RubisCO in Pseudomonas hydrogenothermophila are followed by a novel cbbQ gene similar to nirQ of the denitrification gene cluster from Pseudomonas species. Gene 153:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]