Abstract

Bacillus subtilis contains three proteins of the signal recognition particle-GTPase family known as Ffh, FtsY, and FlhF. Here we show that FlhF is dispensable for protein secretion, unlike Ffh and FtsY. Although flhF is located in the fla/che operon, B. subtilis 168 flhF mutant cells assemble flagella and are motile.

In eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and archaea, a large number of proteins is transported across membranes in order to fulfill their biological function. Complex and well-organized protein transport systems have evolved for membrane translocation of these proteins. Most proteins that play a role outside the cytoplasm contain a signal peptide, which directs the (pre)protein to its final destination (2, 23, 28, 29). Chaperones and targeting factors recognize this signal peptide and keep preproteins in an export-competent state before targeting to the translocation machinery in the membrane. The major machinery for protein transport is the Sec translocase, which handles preproteins in an unfolded state (7).

On the basis of proteomic studies, it has been proposed that the majority of secretory proteins of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis are targeted to the Sec translocase by the so-called signal recognition particle (SRP) (9). This SRP seems to be involved in preprotein targeting to membranes of organisms belonging to all three domains of life. The B. subtilis SRP complex consists of the Ffh (Fifty-four homolog) protein (10), a small cytoplasmic RNA (scRNA) (15, 16), and a histone-like protein (HBsu) (17). Preprotein targeting by this SRP complex presumably involves the presence of the SRP receptor-like protein FtsY (18). Both Ffh and FtsY belong to the widely conserved family of SRP-GTPases (8). Interestingly, B. subtilis and several other bacterial species (but not Escherichia coli) contain a third gene encoding a protein belonging to the SRP-GTPase family. In B. subtilis, this paralogue of Ffh and FtsY was named FlhF (flagellum-associated protein) because it appeared to be required for the flagellar assembly and motility of this bacterium (5). Specifically, the B. subtilis FlhF protein has 46% identical residues and conservative replacements in a stretch of 175 residues with B. subtilis Ffh and 37% identical residues and conservative replacements in a stretch of 318 residues with B. subtilis FtsY. As shown by sequence alignments and domain searches, FlhF contains the conserved N and G domains of the SRP-like GTPases (Fig. 1). However, it lacks the so-called M domain typical for the C termini of Ffh-like proteins and contains a basic B domain instead of the acidic A domain of FtsY-like proteins of bacteria and yeasts. Notably, the mammalian SRP receptor SRα contains a more basic N-terminal domain, like FlhF of B. subtilis. Consistent with its proposed function, the flhF gene is located within the che/fla operon, which encodes the majority of the chemotaxis and flagellar proteins (11). Pandza and coworkers (20) showed that the FlhF homologue of Pseudomonas putida has a role in polar flagellar placement and in induction of the general stress response.

FIG. 1.

Conserved domains in proteins of the SRP-GTPase family. The SRP-GTPase family members of yeast (SRP54, SRα), E. coli (P48, FtsY_Ec), and B. subtilis (Ffh, FlhF, FtsY_Bs) are represented schematically. Different domains that can be distinguished are the acidic A domain; the basic B domain, the conserved N domain, the M domain involved in RNA and preprotein binding, and the GTP-binding G domain. The five conserved boxes, G1 to G5, in the G domain, as defined by Eichler and Moll (8), are shown.

On the basis of the similarity between FlhF and Ffh/FtsY, Carpenter et al. (5) proposed that FlhF might be involved in protein secretion. Notably, however, FlhF is dispensable for growth and viability, whereas Ffh and FtsY are essential, like the key components SecA, SecY, and SecE of the Sec translocase (12). This raised the questions of whether and, if so, to what extent FlhF is involved in protein secretion.

Construction of a B. subtilis 168 flhF mutant.

Since all of our previous studies on protein secretion by B. subtilis were performed with sequenced strain 168 (13), a B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat mutant strain was constructed by transforming B. subtilis 168 with chromosomal DNA of flhF mutant strain OI2735, which was constructed by Carpenter et al. (5) (Table 1). B. subtilis 168 was transformed as previously described (22). Chloramphenicol-resistant transformants were screened by PCR with primers cat1 (5′-GAT TTA GAC AAT TGG AAG) and cat2 (5′-GAC AAT TCC TGA ATA GAG) to show the presence of the cat gene (data not shown). PCR was carried out with the Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche) as described previously (26).

TABLE 1.

Plasmid and bacterial strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Relevant propertiesa | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pKTH10 | Encodes α-amylase AmyQ of B. amyloliquefaciens, 6.8 kb; Kmr | 19 |

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | 13 |

| OI2735 | flhF::cat Cmr | 5 |

| 168 flhF::cat | Like 168; flhF::cat Cmr | This paper |

| BFA2616 | Like 168; ylxH::pMutin2 Emr | 12 |

| BFA2616 flhF::cat | Like BFA2616; flhF::cat Cmr Emr | This paper |

| DB430 | Like 168; nprE aprE bpf isp1 | 6 |

| DB430 flhF::cat | Like DB430; flhF::cat Cmr | This paper |

Kmr, kanamycin resistance (20 μg/ml); Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance (5 μg/ml); Emr, erythromycin resistance (2 μg/ml).

FlhF is not required for protein secretion by B. subtilis strains 168 and DB430.

To investigate the involvement of FlhF in protein secretion, the composition of the extracellular proteome of B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat was analyzed and compared to that of parental strain 168. In addition, similar experiments were performed with protease-deficient strain DB430 and a DB430 flhF::cat derivative that was obtained by transformation of strain DB430 with chromosomal DNA of strain OI2735. For analysis of their extracellular proteomes, all strains were grown at 37°C under vigorous agitation in rich medium. After 1 h of postexponential growth, cells were separated from the growth medium by centrifugation and proteins secreted into the growth medium were concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. The resulting samples were used for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and protein spots were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and/or N-terminal sequencing as previously described (1). After dual-channel imaging to visualize possible changes in the extracellular protein composition, no major differences were observed between the extracellular proteomes of the flhF::cat mutants and the respective parental strains, 168 and DB430 (Fig. 2A). Under the conditions tested, some fluctuation in the levels of prophage-encoded proteins XkdK, XkdG, XkdM, and YolA was observed in the growth media of flhF mutant strains, as well as in the media of parental strains 168 and DB430 (Fig. 2B). Most likely, this reflects fluctuations in the expression of genes located on the PBSX prophage (xkdK, xkdG, and xkdM) and the SPβ prophage (yolA). Unexpectedly, the extracellular accumulation of proteins known to be required for cell motility, such as FlgK (flagellar hook-associated protein 1), FliD (flagellar hook-associated protein 2), and the flagellin Hag, was not affected by the absence of FlhF.

FIG. 2.

Extracellular proteome of B. subtilis flhF::cat. The extracellular proteins of the flhF::cat mutant strains and the respective parental strains 168 and DB430 were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, after which dual-channel fluorescence imaging was used to visualize possible changes in extracellular protein composition (3). Protein spots identified by mass spectrometry and/or N-terminal sequencing are indicated. Green protein spots are predominantly present in the image of the extracellular proteins of the parental strain, red protein spots are predominantly present in the image of the extracellular proteins of the flhF mutant strain, and yellow protein spots are present in similar amounts in both images. (A) Extracellular proteomes of B. subtilis DB430 and DB430 flhF::cat. (B) Variable extracellular levels of prophage-encoded proteins YolA, XkdM, XkdG, and XkdK (top to bottom).

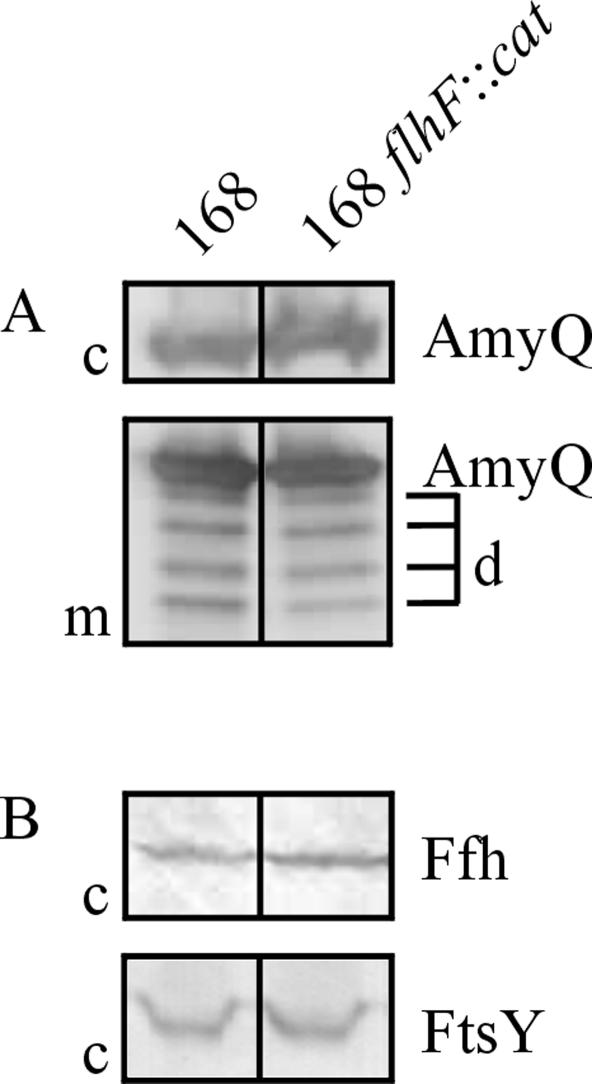

It was previously shown that the absence of some components of the Sec machinery of B. subtilis, such as SecDF (4) and SecG (27), has no detectable effect on protein secretion unless the secretion machinery is challenged with overproduced secretory proteins. For example, this was shown by high-level expression of the α-amylase AmyQ of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (4) with plasmid pKTH10 (Table 1). To study the importance of FlhF for AmyQ secretion at high levels, the flhF mutant strain and parental strain 168 were transformed with pKTH10. After overnight growth in TY medium (1% Bacto Tryptone, 0.5% Bacto Yeast Extract, 1% NaCl) supplemented with kanamycin, cells and medium fractions were separated by centrifugation (2 min, 16,000 × g, room temperature). Next, protein samples for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were prepared as described previously (25). After separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a Protran nitrocellulose transfer membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) as described by Kyhse-Andersen (14). AmyQ was visualized with specific antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugates (BioSource International). As shown in Fig. 3A, disruption of the flhF gene affects neither the amounts of AmyQ secreted into the growth medium nor the amounts of AmyQ present in the cells. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that FlhF is dispensable for protein secretion, even when the secretion machinery of B. subtilis is challenged by the high-level production of a secretory protein.

FIG. 3.

Absence of FlhF has no impact on secretion of AmyQ and cellular levels of Ffh and FtsY. The secretion of overproduced AmyQ (A) and the intracellular levels of Ffh and FtsY (B) were analyzed by Western blotting with cellular (c) and/or growth medium (m) fractions of B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat and parental strain 168. d, degradation products of AmyQ.

Since FlhF is a paralogue of Ffh and FtsY, it is conceivable that the B. subtilis cell can suppress the effects of the absence of FlhF by production of Ffh or FtsY at increased levels. To study possible changes in the levels of Ffh and FtsY in the absence of FlhF, Western blotting experiments were performed. For this purpose, overnight cultures of B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat and parental strain 168 were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05 and grown until 1 h after the transition between exponential and postexponential growth. Subsequently, cells were collected by centrifugation and prepared for Western blotting as indicated above. Ffh and FtsY were visualized with specific antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (BioSource International) and a standard nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside reaction (21). The results demonstrate that the intracellular levels of Ffh and FtsY are not affected by disruption of the flhF gene (Fig. 3B). Consequently, it can be concluded that B. subtilis cells do not compensate for the absence of FlhF by upregulation of the production of Ffh and/or FtsY. However, complementation of the flhF mutation by the production of Ffh and/or FtsY at normal levels cannot be ruled out.

FlhF has a minor role in the motility of strain 168.

As the flhF mutation in B. subtilis OI2735 was shown to result in nonmotility, we verified whether the same would be true for cells of B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat by using a motility plate assay. B. subtilis cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in TY medium. Next, the optical density at 600 nm was measured and adjusted to 1.0 with fresh TY medium. Subsequently, an aliquot of 2 μl was spotted onto TY plates containing 0.27% agar (supplemented with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG] when appropriate). Finally, after incubation for 12 h at 37°C, the swarming distances of the different strains were compared (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the report of Carpenter et al. (5), B. subtilis flhF mutant strain OI2735 is nonmotile. Remarkably, however, disruption of the flhF gene in B. subtilis 168 has no effect on cell motility (Fig. 4A). Moreover, scanning electron microscopy shows that B. subtilis 168 flhF::cat produces apparently intact flagella (data not shown). These observations imply that there are substantial differences in the genetic backgrounds of the two flhF mutant strains. To investigate whether genes downstream of flhF might be involved in this phenomenon, the motility of B. subtilis 168 with an integrated copy of the pMutin2 plasmid in the ylxH gene (strain BFA2616; Fig. 4B) was tested. As shown in Fig. 4A, the motility of strain BFA2616 was significantly reduced compared to that of B. subtilis 168. However, induction of the transcription of genes downstream of ylxH by activation of the pMutin2-derived Pspac promoter with IPTG resulted in less severely impaired motility of the cells. This shows that the YlxH protein has a role in cell motility. In addition to YlxH, proteins encoded by genes downstream of the ylxH gene are required for motility. To further investigate a possible role of FlhF in this process, the BFA2616 flhF::cat double mutant was constructed by transformation of strain BFA2616 with chromosomal DNA of strain OI2735. Irrespective of the presence of IPTG to induce transcription of genes downstream of ylxH, the motility of cells of the double-mutant strain was more severely affected than that of strain BFA2616 cells. It has to be noted, however, that upon incubation of the swarming plates for 24 h some motility of the BFA2616 flhF::cat double mutant was observed when it was grown in the presence of IPTG. In contrast, strain OI2735 displayed no motility at all. The fact that the flhF single mutation had no effect on motility while the combined flhF and ylxH mutations affected motility more severely than the ylxH single mutation indicates that the functions of FlhF and YlxH overlap at least partly. In this respect, it is interesting that YlxH has a putative nucleotide binding site, like FlhF. If FlhF and YlxH act cooperatively, the function of FlhF can be taken over by YlxH in flhF mutant cells, but the opposite seems not to occur. Remarkably, integration of the pMutin plasmid into the ylxH gene appears to result in a polar effect on the expression of downstream genes, while there is no evidence for polar effects upon integration of the cat gene into flhF. Nevertheless, transcriptome analyses with B. subtilis strain 168, as documented on the JAFAN website (http://bacillus.genome.jp/), show that the expression profiles of flhF and ylxH, as well as the surrounding genes, are highly similar under the 10 different growth conditions tested. This strongly suggests that these genes are part of one operon or regulon. Moreover, studies by West and coworkers (30) support the idea that the expression of flhF and ylxH is controlled by one promoter. Taken together, our observations demonstrate that FlhF has a minor role in the motility of B. subtilis 168 cells. It is not clear why disruption of flhF in strain OI2735 results in a complete block of motility (5).

FIG. 4.

Motility assays. (A) Comparison of the motilities of B. subtilis strains 168, OI2735, 168 flhF::cat, BFA2616 (grown in the absence or presence of 1 mM IPTG), and BFA2616 flhF::cat (grown in the absence or presence of 1 mM IPTG) after 12 h of incubation on 0.27% agar plates at 37°C. (B) Schematic representation of ylxH gene disruption by pMutin2 via Campbell-type integration. lacI, E. coli lacI gene; ori pBR322, origin of replication of plasmid pBR322; ApR, ampicillin resistance marker; EmR, erythromycin resistance marker; t1t2, transcriptional terminators on pMutin2; Pspac, IPTG-dependent promoter; Pfla/che, promoter of the fla/che operon; ylxH′, 3′-truncated ylxH gene; ′ylxH, 5′-truncated ylxH gene; flhF, flhF gene; cheB, cheB gene.

In conclusion, our combined proteomic and biochemical analyses of sequenced B. subtilis strain 168 demonstrate that FlhF, the third SRP-GTPase of this organism, is dispensable for protein secretion and has a minor role in cell motility. It remains to be investigated whether FlhF has a role in the biogenesis of membrane proteins, as shown for its homologues Ffh and FtsY in E. coli (24) and proposed for gram-positive bacteria (28).

Acknowledgments

We thank George Ordal for providing B. subtilis strain OI2735 and Marc Kolkman from Genencor International for providing anti-Ffh and anti-FtsY antibodies. Jan Jongbloed, Joen Luirink, Rob Meima, and Bauke Oudega are thanked for helpful discussions.

G.Z. and W.J.Q. were supported by the Stichting Technische Wetenschappen (BVI.4837), H.W. and J.M.V.D. were supported by the CEU (BIO4-CT98-0250, QLK3-CT-1999-00413, and QLK3-CT-1999-00917), and H.A. and M.H. were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft, Forschung und Technologie, and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antelmann, H., H. Tjalsma, B. Voigt, S. Ohlmeier, S. Bron, J. M. van Dijl, and M. Hecker. 2001. A proteomic view on genome-based signal peptide predictions. Genome Res. 11:1484-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blobel, G., and B. Dobberstein. 1975. Transfer to proteins across membranes. II. Reconstitution of functional rough microsomes from heterologous components. J. Cell Biol. 67:852-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum, H., H. Beier, and H. J. Gross. 1987. Improved silver staining of plant- proteins, RNA and DNA polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8:93-99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolhuis, A., C. P. Broekhuizen, A. Sorokin, M. L. van Roosmalen, G. Venema, S. Bron, W. J. Quax, J. M. van Dijl. 1998. SecDF of Bacillus subtilis, a molecular Siamese twin required for the efficient secretion of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21217-21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter, P. B., D. W. Hanlon, and G. W. Ordal. 1992. flhF, a Bacillus subtilis flagellar gene that encodes a putative GTP-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2705-2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doi, R. H., S. L. Wong, and F. Kawamura. 1986. Potential use of Bacillus subtilis for secretion and production of foreign proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 4:232-235. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen, A. J., E. H. Manting, and C. van der Does. 2001. The structural basis of protein targeting and translocation in bacteria. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichler, J., and R. Moll. 2001. The signal recognition particle of Archaea. Trends Microbiol. 9:130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose, I., K. Sano, I. Shioda, M. Kumano, K. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 2000. Proteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis extracellular proteins: a two-dimensional protein electrophoretic study. Microbiology 146:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honda, K., K. Nakamura, M. Nishiguchi, and K. Yamane. 1993. Cloning and characterization of a Bacillus subtilis gene encoding a homolog of the 54-kilodalton subunit of mammalian signal recognition particle and Escherichia coli Ffh. J. Bacteriol. 175:4885-4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirsch, M. L., P. B. Carpenter, and G. W. Ordal. 1994. A putative ATP-binding protein from the che/fla locus of Bacillus subtilis. DNA Sequence 4:271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi, K., S. D. Ehrlich, A. Albertini, G. Amati, K. K. Andersen, M. Arnaud, K. Asai, S. Ashikaga, S. Aymerich, P. Bessieres, F. Boland, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, K. Bunai, J. Chapuis, L. C. Christiansen, A. Danchin, M. Debarbouille, E. Dervyn, E. Deuerling, K. Devine, S. K. Devine, O. Dreesen, J. Errington, S. Fillinger, et al. 2003. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4678-4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, A. Danchin, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyhse-Andersen, J. 1984. Electroblotting of multiple gels: a simple apparatus without buffer tank for rapid transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide to nitrocellulose. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 10:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura, K., Y. Imai, A. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 1992. Small cytoplasmic RNA of Bacillus subtilis: functional relationship with human signal recognition particle 7S RNA and Escherichia coli 4.5S RNA. J. Bacteriol. 174:2185-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura, K., M. Nishiguchi, K. Honda, and K. Yamane. 1994. The Bacillus subtilis SRP54 homologue, Ffh, has an intrinsic GTPase activity and forms a ribonucleoprotein complex with small cytoplasmic RNA in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199:1394-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura, K., S. Yahagi, R. Yamazaki, and K. Yamane. 1999. Bacillus subtilis histone-like protein, HBsu, is an integral component of a SRP-like particle that can bind the Alu domain of small cytoplasmic RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13569-13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura, A., H. Kakeshita, K. Honda, H. Takamatsu, K. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 1995. srb: a Bacillus subtilis gene encoding a homologue of the alpha-subunit of the mammalian signal recognition particle receptor. DNA Res. 2:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palva, I. 1982. Molecular cloning of α-amylase gene from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and its expression in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 19:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandza, S., M. Baetens, C. H. Park, T. Au, M. Keyhan, and A. Matin. 2000. The G-protein FlhF has a role in polar flagellar placement and general stress response induction in Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 36:414-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Tjalsma, H., A. Bolhuis, M. L. van Roosmalen, T. Wiegert, W. Schumann, C. P. Broekhuizen, W. J. Quax, G. Venema, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 1998. Functional analysis of the secretory precursor processing machinery of Bacillus subtilis: identification of a eubacterial homolog of archaeal and eukaryotic signal peptidases. Genes Dev. 12:2318-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tjalsma, H., A. Bolhuis, J. D. H. Jongbloed, S. Bron, and J. M. van Dijl. 2000. Signal peptide-dependent protein transport in Bacillus subtilis: a genome-based survey of the secretome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:515-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valent, Q. A., J. W. de Gier, G. von Heijne, D. A. Kendall, C. M. ten Hagen-Jongman, B. Oudega, and J. Luirink. 1997. Nascent membrane and presecretory proteins synthesized in Escherichia coli associate with signal recognition particle and trigger factor. Mol. Microbiol. 25:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dijl, J. M., A. de Jong, H. Smith, S. Bron, and G. Venema. 1991. Non-functional expression of Escherichia coli signal peptidase I in Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2073-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dijl, J. M., A. de Jong, G. Venema, and S. Bron. 1995. Identification of the potential active site of the signal peptidase SipS of Bacillus subtilis: structural and functional similarities with LexA-like proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3611-3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Wely, K. H. M., J. Swaving, C. P. Broekhuizen, M. Rose, W. J. Quax, and A. J. M. Driessen. 1999. Functional identification of the product of the Bacillus subtilis yvaL gene as a SecG homologue. J. Bacteriol. 181:1786-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Wely, K. H., J. Swaving, R. Freudl, and A. J. Driessen. 2001. Translocation of proteins across the cell envelope of gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:437-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Heijne, G. 1998. Life and death of a signal peptide. Nature 396:111-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West, J. T., W. Estacio, and L. Márquez-Magaña. 2000. Relative roles of the fla/che PA, PD-3, and PsigD promoters in regulating motility and sigD expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4841-4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]