Abstract

We have investigated the regulation of the S10 and spc ribosomal protein (r-protein) operons in Vibrio cholerae. Both operons are under autogenous control; they are mediated by r-proteins L4 and S8, respectively. Our results suggest that Escherichia coli-like strategies for regulating r-protein synthesis extend beyond the enteric members of the gamma subdivision of proteobacteria.

In organisms as diverse as eubacteria, archaea, protist cyanelles, chloroplasts, and mitochondria, clusters of ribosomal protein (r-protein) genes are remarkably similar in organization (10, 23, 24). In spite of this striking degree of conservation, the mechanisms behind the expression of these genes are clearly diverse, since the positions of promoters and terminators are not well conserved. For example, in Escherichia coli, 28 r-protein genes in the S10-spc-alpha cluster are organized into three transcription units (12), but the corresponding genes in Bacillus subtilis are organized into a single transcription unit (8, 11, 21).

In E. coli, most of the r-proteins are under autogenous control. That is, for a given r-protein operon, a specific r-protein has evolved to function not only as a component of the ribosome, but also as a regulatory protein responsible for coordinating expression of its operon with the availability of rRNA and other r-proteins (28). The 11-gene S10 operon of E. coli is regulated by r-protein L4, a component of the large ribosomal subunit, and encoded by the third gene of the operon. Unlike other autogenously controlled r-protein operons, which are regulated at the level of translation, the S10 operon is subject to both transcriptional and translational regulation (30). The two control mechanisms require partially overlapping but distinct determinants within the 172-base nontranslated region of the S10 mRNA (3, 19).

Previous studies have suggested that L4 proteins from species as divergent from E. coli as Bacillus stearothermophilus have maintained the determinants required for autogenous control of the S10 operon in E. coli (11, 31). However, the autogenous control mechanism itself appears not to be so well conserved. For example, examination of potential secondary structures of RNA upstream of the S10 gene in other eubacterial species suggests that only a subset of species, confined to some members of the gamma branch of proteobacteria, have the structural determinants in the S10 leader that are necessary for L4-mediated autogenous control in E. coli (reference 1 and unpublished data). Moreover, when heterologous S10 leaders which can form those critical secondary structures are introduced into E. coli, they function as regulatory targets for L4, while those that do not have the potential to form the structures found in the E. coli S10 leader do not function as regulatory elements (1, 11).

To directly address the mechanism for regulating r-protein synthesis within other eubacteria, we characterized the regulation of the S10 and spc operons in Vibrio cholerae, the most divergent of the gamma proteobacteria we suspected of using the same mechanism as E. coli (1).

Regulation of the V. cholerae S10 operon.

V. cholerae has a cluster of 11 r-protein genes that correspond in order to the 11 genes of the E. coli S10 operon (Fig. 1A). We mapped the transcription start site for this gene cluster by primer extension analysis of chromosome-derived RNA from V. cholerae strain JBK70 (ΔCTXAB::mer; a gift from J. B. Kaper, University of Maryland School of Medicine). This analysis identified an A 271 bases upstream of the S10 start codon as the first nucleotide of the transcript (data not shown). This nucleotide is almost exactly at the position of the transcription start site predicted by sequence gazing. Although the V. cholerae leader is significantly longer than the E. coli leader, the predicted secondary structure of the region containing hairpins HD, HE, and HG is remarkably similar to the E. coli structure (Fig. 1B and C) (1).

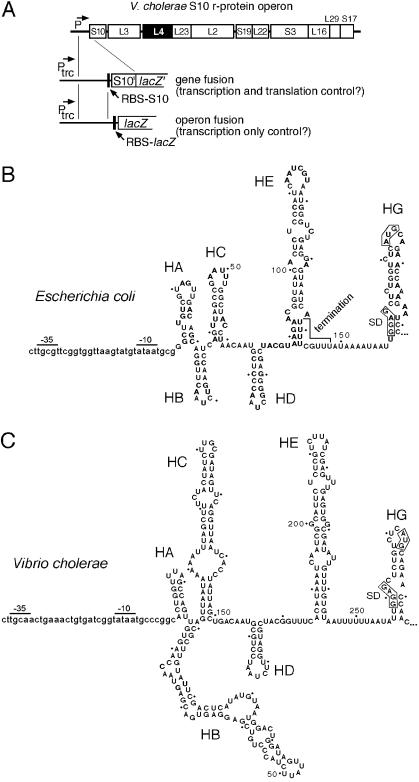

FIG. 1.

(A) Maps of the V. cholerae S10 operon and plasmids used for targets of L4-mediated regulation. The reporter gene (S10′/lacZ′ or lacZ) is expressed from the IPTG-inducible trc promoter (Ptrc). RBS-S10 and RBS-lacZ refer to the Shine-Dalgarno regions of the S10 and lacZ genes, respectively. (B and C) Promoter and leader regions of the V. cholerae and E. coli S10 operons. The secondary structures of the leaders from E. coli and V. cholerae were described previously (1). The DNA sequences upstream of the transcription start site are shown in lowercase letters, with the presumptive −35 and −10 sequences indicated. The transcribed regions are shown in uppercase letters. The boxed sequences indicate the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence and the AUG initiation codon of the S10 structural gene.

Overexpression of r-protein L4 in E. coli inhibits expression of the 11-gene S10 operon, preventing synthesis of new ribosomes and, as a result, preventing colony formation. To test for L4-mediated autogenous control in V. cholerae, we cloned the V. cholerae L4 gene under control of the arabinose promoter on plasmid pBAD18 (6). Induction of the resulting plasmid with arabinose in either V. cholerae or E. coli resulted in inhibition of growth (Fig. 2), suggesting that L4 inhibits expression of the S10 operon in V. cholerae.

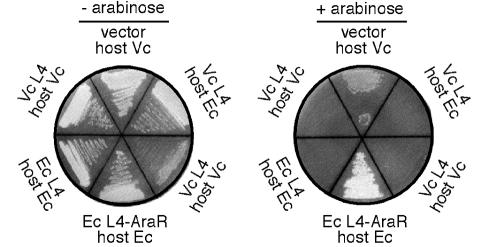

FIG. 2.

Growth of cells carrying Para-L4 plasmids. Either E. coli (Ec) or V. cholerae (Vc) host cells carrying an arabinose-inducible L4 gene from the indicated source were streaked on Luria-Bertani plates with or without arabinose and incubated at 37°C for about 24 h. E. coli L4-AraR is a regulatory-defective mutant of the E. coli L4 protein (25).

To more directly analyze the effect of excess L4 on expression of the S10 operon in V. cholerae, we tested the effect of arabinose induction of L4 on expression of an S10 leader-S10′/lacZ′ reporter construct (Fig. 1A). The V. cholerae (or E. coli) S10 leader and proximal 54 codons of the S10 gene were amplified by PCR and cloned downstream of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible Ptrc promoter, in frame with lacZ′. The resulting plasmid, a derivative of pACYC-Bsu (Fig. 1) (1, 11), is compatible with the pBAD18-L4 plasmid. The absence of a lac repressor in V. cholerae resulted in constitutive expression of the S10′/lacZ′ reporter. Although the constitutive expression did not seem to negatively affect growth, we also constructed a plasmid containing a lacIq gene in addition to the V. cholerae S10′/lacZ′ gene, making expression of the S10′/lacZ′ reporter IPTG inducible. Since these plasmids are colE1 derivatives, we transferred the PBAD-L4 operons to a compatible pACYC177 vector. Both sets of plasmids yielded essentially the same results.

We measured L4-mediated regulation by pulse-labeling exponentially growing cells carrying the S10 leader reporter and L4 source plasmids with [35S]methionine before and 10 min after addition of arabinose to induce L4 synthesis (1, 27). The autoradiogram in Fig. 3A shows that induction of L4 in V. cholerae does indeed repress expression of the S10′/β-Gal′ fusion protein. The fusion protein migrates very close to another unrelated V. cholerae protein, so quantitation in this species is less reliable than in E. coli. Nevertheless, induction of L4 in V. cholerae results in approximately fourfold inhibition. We conclude from these experiments that V. cholerae employs L4-mediated autogenous control of its S10 operon.

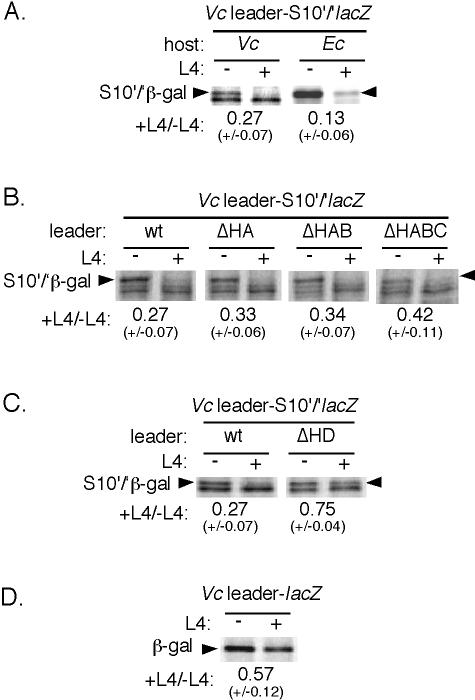

FIG. 3.

Regulation of the E. coli (Ec) and V. cholerae (Vc) S10 operons mediated by L4. E. coli or V. cholerae strains with the indicated reporter plasmids and L4 sources were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine before (−) or 10 min after (+) induction of L4 by addition of arabinose. Extracts were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis. The radioactivity in each S10′/lacZ′ or lacZ fusion protein band was normalized to the total radioactivity in the same lane. L4-mediated regulation (+L4/−L4) was expressed as the normalized radioactivity in the fusion band after L4 induction divided by the normalized radioactivity in the fusion band before L4 induction. Each experiment was performed at least four times. The standard deviations are shown in parentheses. (A) E. coli or V. cholerae cells carrying the V. cholerae leader-S10′/lacZ′ plasmid and a Para plasmid harboring the V. cholerae L4 gene. (B) V. cholerae cells carrying an S10′/lacZ′ plasmid with the wild-type (wt) V. cholerae leader or the V. cholerae leader containing a deletion of the indicated hairpins. (C) V. cholerae cells carrying an S10′/lacZ′ plasmid with either the wild-type V. cholerae leader or a V. cholerae leader with a deletion of the HD hairpin. The L4 source was V. cholerae. (D) V. cholerae cells carrying an operon fusion plasmid with the wild-type V. cholerae leader.

In E. coli, only the region downstream of hairpin HC (Fig. 1) is required for L4-mediated regulation (29). Considering that the V. cholerae S10 leader is significantly longer than the leader in E. coli, we wondered if the additional sequences are required for regulation of the V. cholerae S10 operon. To test this possibility, we systematically deleted one, two, or all three of the promoter proximal hairpins of the V. cholerae S10 leader on the pACYC S10′/lacZ′ plasmid, using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). As shown in Fig. 3B, deletions removing hairpins HA, HB, and HC in the V. cholerae S10 leader still allowed L4 inhibition of expression. That is, like in E. coli, the first three hairpins of the V. cholerae leader are not required for L4-mediated autogenous control.

Hairpin HD is required for efficient L4 control of transcription in E. coli (29) and is essential for binding of L4 to the S10 leader in vitro (20), but deletion of HD has little effect on translation (29). We deleted hairpin HD from the V. cholerae leader and observed significantly reduced inhibition of expression of the fusion protein (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that L4 regulates expression of the V. cholerae S10 operon by invoking premature termination of transcription, as in E. coli. The residual regulation in the hairpin HD deletion mutant might reflect still-intact translation control.

As a more direct test for L4-mediated transcription control in V. cholerae, we constructed a plasmid with an operon fusion placing the V. cholerae S10 leader from nucleotides 1 to 260 upstream of the complete lacZ gene, including the lac Shine-Dalgarno sequence, on plasmid pTrc99A-lacZ (Fig. 1). L4 induction resulted in about twofold reduction of lacZ expression (Fig. 3D). We conclude that the V. cholerae S10 operon is subject to L4-mediated transcription regulation.

Regulation of the spc operon of V. cholerae.

Having found that the S10 operon of V. cholerae is autogenously regulated by a process homologous to the E. coli mechanism, we wondered if other V. cholerae r-protein operons also share autogenous control mechanisms. We chose the spc operon (Fig. 4A), which in E. coli is regulated at the level of translation by the binding of r-protein S8 to a hairpin in the mRNA that includes the initiation codon of S5 (2, 5, 17). This hairpin has obvious structural similarities to the demonstrated S8 binding site in 16S rRNA (Fig. 4B) (9, 16, 18, 26). Comparison of the sequences of the spc operons showed that a hairpin similar to the S8 target hairpin of E. coli could form in V. cholerae (Fig. 4B).

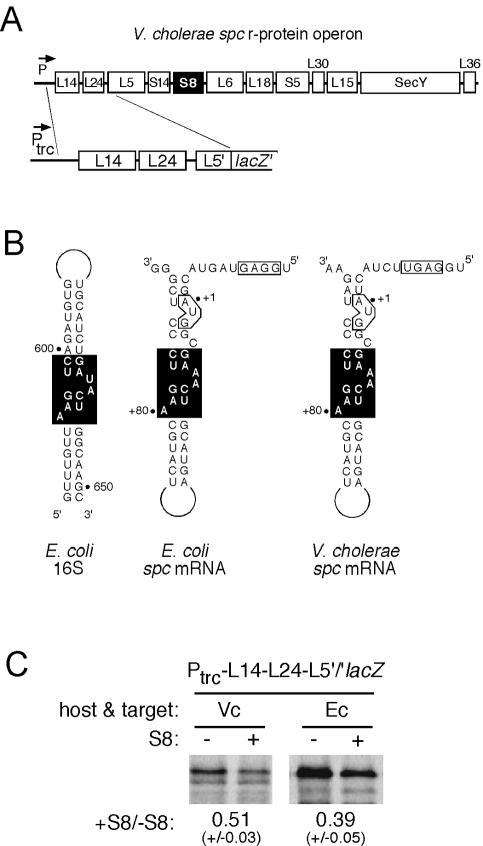

FIG. 4.

(A) Maps of the V. cholerae spc operon and the plasmid used for the target of S8-mediated regulation. The map of the spc operon is based on the genome sequence reported by Heidelberg et al. (7). (B) Secondary structures of the S8 targets in 16S rRNA and spc mRNA. The core binding regions of S8 on E. coli 16S (4, 9, 15) and on E. coli spc mRNA (5) are indicated by filled boxes. The same region is also required for S8-mediated regulation of the spc operon in E. coli (2, 26). As an analogy, the same region is indicated on the V. cholerae mRNA. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the initiation codon of the L5 gene are indicated by open boxes. (C) Regulation of the E. coli (Ec) and V. cholerae (Vc) spc operons mediated by S8. E. coli or V. cholerae strains with the indicated target reporter plasmid and S8 source were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine before (−) or 10 min after (+) induction of S8 by addition of arabinose. The radioactivity in each L5′/lacZ′ band was normalized to the total radioactivity in the same lane. S8-mediated regulation (+S8/−S8) was expressed as the normalized radioactivity in the fusion band after S8 induction divided by the normalized radioactivity in the fusion band before S8 induction. Each experiment was performed at least two times. The standard deviations are shown in parentheses.

To analyze S8-mediated regulation of the S8 operons of E. coli and V. cholerae, we inserted the proximal end of the operon, including the leader, intact genes for L14 and L24, and proximal 66 codons of L5, into pACYC-Bsu (11), resulting in the creation of an L5′/lacZ′ fusion gene (Fig. 4A). These plasmids were then introduced into E. coli and V. cholerae strains also harboring a Para-S8 plasmid, constructed by cloning the E. coli or V. cholerae S8 gene into pBAD18 (6). Pulse-labeling experiments showed that arabinose induction of S8 in E. coli results in almost threefold inhibition of fusion protein synthesis (Fig. 4C), similar to the fivefold reduction reported previously (13, 14). Induction of S8 in V. cholerae results in a twofold inhibition of L5′/β-gal′ synthesis. We conclude that the spc operon of V. cholerae is autogenously regulated by S8, presumably in a fashion similar to what has been described for E. coli.

Summary.

These and earlier studies (1) suggest that the E. coli-type mechanisms for L4-mediated regulation of the S10 operon and S8-mediated regulation of the spc operon are widespread among the gamma subdivision of the proteobacteria. However, these mechanisms are not universal to this group, since Pseudomonas aeruginosa does not utilize the E. coli-like mechanism for S10 operon control (1). Inspection of the sequence preceding the L5 gene in the spc operon of P. aeruginosa appears to be incompatible with the structure of the S8 target in the spc mRNA, suggesting that the spc operon of P. aeruginosa also does not follow the E. coli paradigm. Tchufistova et al. (22) recently reported that an E. coli-like autogenous control mechanism for regulating the S1 r-protein gene operates in a number of species of the gamma proteobacteria, but, again, not in the Pseudomonas group. Taken together, these observations suggest that autogenous regulatory mechanisms governing the expression of E. coli r-proteins evolved in a common ancestor which gave rise to some, but not all, gamma proteobacteria. The contrast between the widespread organization of the major r-protein gene cluster and the much more limited distribution of the E. coli regulatory paradigms suggests that the regulatory mechanisms developed much later than the gene cluster itself.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Kaper for the V. cholerae strain.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute for General Medical Science and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, T., P. Shen, L. Samsel, R. Liu, L. Lindahl, and J. M. Zengel. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of L4-mediated autogenous control of the S10 ribosomal protein operon. J. Bacteriol. 181:6124-6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerretti, D. P., L. C. Mattheakis, K. R. Kearney, L. Vu, and M. Nomura. 1988. Translational regulation of the spc operon in Escherichia coli: identification and structural analysis of the target site for S8 repressor protein. J. Mol. Biol. 204:309-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman, L. P., J. M. Zengel, R. H. Archer, and L. Lindahl. 1987. Autogenous control of the S10 ribosomal protein operon of Escherichia coli: genetic dissection of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:6516-6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory, R. J., and R. A. Zimmermann. 1986. Site-directed mutagenesis of the binding site for ribosomal protein S8 within 16S ribosomal RNA from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:5761-5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregory, R. R., P. B. F. Cahill, D. L. Thurlow, and R. A. Zimmermann. 1988. Interaction of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S8 with its binding sites in ribosomal RNA and messenger RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 204:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman, L.-M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkin, T. M., S. H. Moon, L. C. Mattheakis, and M. Nomura. 1989. Cloning and analysis of the spc ribosomal protein operon of Bacillus subtilis: comparison with the spc operon of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:7469-7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalurachchi, K., K. Uma, R. A. Zimmermann, and E. P. Nikonowicz. 1997. Structural features of the binding site for ribosomal protein S8 in Escherichia coli 16S rRNA defined using NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2139-2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koonin, E. V., and M. Y. Galperin. 1997. Prokaryotic genomes: the emerging paradigm of genome-based microbiology. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7:757-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, X., L. Lindahl, Y. Sha, and J. M. Zengel. 1997. Analysis of the Bacillus subtilis S10 ribosomal protein gene cluster identifies two promoters that may be responsible for transcription of the entire 15-kilobase S10-spc-α cluster. J. Bacteriol. 179:7046-7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindahl, L., F. Sor, R. H. Archer, M. Nomura, and J. M. Zengel. 1990. Transcriptional organization of the S10, spc and alpha operons of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1050:337-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattheakis, L., L. Vu, F. Sor, and M. Nomura. 1989. Retroregulation of the synthesis of ribosomal proteins L14 and L24 by feedback repressor S8 in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:448-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattheakis, L. C., and M. Nomura. 1988. Feedback regulation of the spc operon in Escherichia coli: translational coupling and mRNA processing. J. Bacteriol. 170:4484-4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moine, H., C. Cachia, E. Westhof, B. Ehresmann, and C. Ehresmann. 1997. The RNA binding site of S8 ribosomal protein of Escherichia coli: selex and hydroxyl radical probing studies. RNA 3:255-268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mougel, M., F. Eyermann, E. Westhof, P. Romby, A. Expert-Bezançon, J.-P. Ebel, B. Ehresmann, and C. Ehresmann. 1987. Binding of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S8 to 16S rRNA. A model for the interaction and the tertiary structure of the RNA binding domain. J. Mol. Biol. 198:91-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olins, P. O., and M. Nomura. 1981. Translational regulation by ribosomal protein S8 in Escherichia coli: structural homology between rRNA binding site and feedback target on mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 9:1757-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recht, M. I., and J. R. Williamson. 2001. Central domain assembly: thermodynamics and kinetics of S6 and S18 binding to an S15-RNA complex. J. Mol. Biol. 313:35-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sha, Y., L. Lindahl, and J. M. Zengel. 1995. RNA determinants required for L4-mediated attenuation control of the S10 r-protein operon of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 245:486-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stelzl, U., J. M. Zengel, M. Tovbina, M. Walker, K. H. Nierhaus, L. Lindahl, and D. J. Patel. 2003. RNA-structural mimicry in ribosomal protein L4-dependent regulation of the S10 operon. J. Biol. Chem. 278:28237-28245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suh, J. W., S. A. Boylan, S. H. Oh, and C. W. Price. 1996. Genetic and transcriptional organization of the Bacillus subtilis spc-α region. Gene 169:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tchufistova, L. S., A. V. Komarova, and I. V. Boni. 2003. A key role for the mRNA leader structure in translational control of ribosomal protein S1 synthesis in gamma-proteobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6996-7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe, H., H. Mori, T. Itoh, and T. Gojobori. 1997. Genome plasticity as a paradigm of eubacteria evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 44(Suppl. 1):S57-S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittmann-Liebold, B., A. K. E. Köpke, E. Arndt, W. Krömer, T. Hatakeyama, and H.-G. Wittmann. 1990. Sequence comparison and evolution of ribosomal proteins and their genes, p. 598-616. In W. E. Hill, A. Dahlberg, R. A. Garrett, P. B. Moore, D. Schlessinger, and J. R. Warner (ed.), The ribosome: structure, function, and evolution. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 25.Worbs, M., M. C. Wahl, L. Lindahl, and J. M. Zengel. 2002. Comparative anatomy of a regulatory ribosomal protein. Biochimie 84:731-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu, H., L. Jiang, and R. A. Zimmermann. 1994. The binding site for ribosomal protein S8 in 16S rRNA and spc mRNA from Escherichia coli: minimum structural requirements and the effects of single bulged bases on S8-RNA interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1687-1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zengel, J. M., and L. Lindahl. 2003. Assay of transcription termination by ribosomal protein L4. Methods Enzymol. 371:356-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zengel, J. M., and L. Lindahl. 1994. Diverse mechanisms for regulating ribosomal protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 47:331-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zengel, J. M., and L. Lindahl. 1996. A hairpin structure upstream of the terminator hairpin required for ribosomal protein L4-mediated attenuation control of the S10 operon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:2383-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zengel, J. M., and L. Lindahl. 1990. Ribosomal protein L4 stimulates in vitro termination of transcription at a NusA-dependent terminator in the S10 operon leader. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2675-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zengel, J. M., D. Vorozheikina, X. Li, and L. Lindahl. 1995. Regulation of the Escherichia coli S10 ribosomal protein operon by heterologous L4 ribosomal proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol. 73:1105-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]