Abstract

The phosphorylated form of NRI is the transcriptional activator of nitrogen-regulated genes in Escherichia coli. NRI∼P displays a slow autophosphatase activity and is rapidly dephosphorylated by the complex of the NRII and PII signal transduction proteins. Here we describe the isolation of two mutations, causing the alterations ΔD10 and K104Q in the receiver domain of NRI, that were selected as conferring resistance to dephosphorylation by the NRII-PII complex. The mutations, which alter highly conserved residues near the D54 site of phosphorylation in the NRI receiver domain, resulted in elevated expression of nitrogen-regulated genes under nitrogen-rich conditions. The altered NRI receiver domains were phosphorylated by NRII in vitro but were defective in dephosphorylation. The ΔD10 receiver domain retained normal autophosphatase activity but was resistant to dephosphorylation by the NRII-PII complex. The K104Q receiver domain lacked both the autophosphatase activity and the ability to be dephosphorylated by the NRII-PII complex. The properties of these altered proteins are consistent with the hypothesis that the NRII-PII complex is not a true phosphatase but rather collaborates with NRI≈P to bring about its dephosphorylation.

The NRII-NRI (NtrB-NtrC) two-component signal transduction system controls expression of the Ntr regulon in response to cellular nitrogen status in Escherichia coli (reviewed in reference 30). The response regulator, NRI, consists of an N-terminal receiver domain, a central ATP-binding AAA+ domain that cleaves ATP and uses this energy to activate transcription by σ54 RNA polymerase, and a C-terminal DNA-binding module that directs the protein to the enhancer sequences from which it acts (23; reviewed in reference 30). NRI is regulated by the reversible phosphorylation of its N-terminal receiver domain (21, 31). Unphosphorylated NRI is dimeric; phosphorylation results in oligomerization of AAA+ domains to form a heptamer (23). Heptameric NRI∼P has ATPase activity and the ability to activate transcription (36).

There are two known routes leading to the phosphorylation (activation) of NRI and two known routes leading to its dephosphorylation (inactivation). One mechanism of phosphorylation is autophosphorylation of NRI with small-molecule phosphodonors. For example, phosphoramidate, carbamyl phosphate, and acetyl phosphate can serve as substrates for the autophosphorylation and activation of NRI in vitro, and acetyl phosphate appears to phosphorylate and activate NRI in vivo (12). Thus, NRI is able to catalyze its own phosphorylation, consistent with earlier results with the related CheY protein (24). Also, NRI can become phosphorylated by transfer of the phosphoryl group from the “transmitter” protein NRII. For this, NRII binds ATP and phosphorylates itself on its highly conserved active-site histidine (His 139), common to two-component systems transmitter proteins, and these phosphoryl groups are transferred to NRI (29, 47). By analogy to CheY, it is likely that NRI catalyzes its own phosphorylation in this reaction as well, with the autophosphorylated NRII serving as the substrate (15). Thus, NRI may be thought of as a “protein phosphatase whose transient covalent intermediate activates transcription” (38). The site of NRI-regulatory phosphorylation is the highly conserved aspartate residue at position 54 within its receiver domain (38).

NRI∼P has a fairly slow “autophosphatase” activity that results in dephosphorylation with a half-life of the phosphoryl groups of about 3.5 to 5 min at 37°C and pH 7.5 (16, 19-21, 47). The autophosphatase activity seems to be catalyzed by NRI∼P itself; when the protein is denatured, or when Mg2+ is chelated with excess EDTA, the half-life of its phosphoaspartate moiety is increased to about 4 to 5 h. In addition to the autophosphatase activity, NRI∼P is very rapidly dephosphorylated by the complex of NRII and the PII signal transduction protein, an activity referred to as regulated phosphatase activity (21, 31). Since the binding of PII to NRII also inhibits NRII autophosphorylation (16, 17, 35), PII may be thought of as converting NRII from an NRI “kinase” to an NRI∼P “phosphatase.” PII is itself regulated by signals of nitrogen status and serves to communicate these signals to NRII (reviewed in reference 30). The kinase and phosphatase activities of the NRII-NRI system have served as a paradigm for many other two-component systems which display similar activities (reviewed in reference 48). The phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of full-length NRI and its isolated receiver domain appear to be approximately the same, and thus studies of these reactions can conveniently use the purified receiver domain (16, 17, 21).

Of the activities listed above, the NRII autophosphorylation activity is best understood. The dimeric NRII consists of three domains connected by linkers: an N-terminal PAS domain, a central dimerization and histidine phosphotransfer domain (Dhp domain or domain A), and a C-terminal ATP-binding domain (kinase domain or domain B) (16). The latter two domains form the transmitter module of NRII. Although the structure of full-length NRII has not yet been determined, the crystal structure of its C-terminal kinase domain, genetic and biochemical data for the protein, and its relatedness to proteins and domains of known structure (3, 7, 27, 29, 42, 43-45) have allowed a reasonable hypothesis for its general organization (35, 42). The autophosphorylation reaction occurs by an obligatory trans-intramolecular mechanism (32) and proceeds by an apparent half-of-the-sites mechanism due to a 70-fold difference in the equilibrium constants for the phosphorylation of the two active sites of the dimer (18). The apparent half-of-the-sites mechanism suggests that there is tight conformational coupling between the different domains of NRII. PII inhibits the autophosphorylation of NRII and activates the regulated phosphatase activity by binding to one of the two C-terminal kinase domains of the NRII dimer (33).

The PII-activated regulated phosphatase activity of NRII is not the reversal of the phosphotransfer activity and seems to be an activity of NRII that PII elicits. The kcat for the regulated phosphatase seems to be about an order of magnitude higher than the kcat for the autophosphorylation reaction (35), and early studies of the regulated phosphatase activity revealed that the phosphoryl groups are released as Pi (21). In the absence of NRII, preparations of the PII protein do not display detectable NRI∼P phosphatase activity. A mutant form of NRII in which the active-site histidine was converted to asparagine (H139N) failed to become phosphorylated when incubated with ATP but could bring about the dephosphorylation of NRI≈P (16, 19). This “basal” phosphatase activity was fairly slow but, like the wild-type regulated phosphatase activity, was stimulated by ATP or noncleavable ATP analogues (16, 19, 21). In the presence of PII and ATP, NRII-H139N brought about the rapid dephosphorylation of NRI∼P (16, 19). This suggests that the active-site histidine is not directly required for the regulated phosphatase activity. Certain fragments of NRII displayed very weak phosphatase activity that was not further stimulated by PII. The smallest common element of these fragments displaying weak phosphatase activity was the Dhp domain itself (16, 21).

Mutations in all domains of NRII can reduce the regulated phosphatase activity of NRII, suggesting that a particular conformation of the protein is required (2, 34). The N-terminal (PAS) domains of the dimer are clearly required, as the purified transmitter module (Dhp plus kinase domains) of NRII displays negligible phosphatase activity in the presence of PII (16). Deletion of the PAS domains also dramatically reduces the asymmetry of autophosphorylation, suggesting that conformational coupling in the molecule is relaxed (16). Numerous mutations in the Dhp domain near the active-site histidine 139 and in the linker region connecting the PAS and Dhp domains reduce the regulated phosphatase activity to various extents (2, 34). Finally, two different surfaces of the kinase domain are revealed by clusters of mutations that block the phosphatase activity (34). One of the kinase domain clusters maps to the ATP lid, while the other identifies a unique β-strand element and adjacent hydrophobic patch on the other side of the domain that probably constitutes the PII-binding site (34, 42).

Studies of purified singly and doubly mutant proteins and heterodimers containing combinations of mutations has provided a clue as to how the domains of NRII collaborate in the regulated phosphatase activity. These studies suggested that PII binds to its site on one of the kinase domains and brings about a global conformational change in NRII that causes the Dhp domain from the PII-bound subunit to collaborate with the ATP lid of the opposing subunit in the dimer to bring about the rapid dephosphorylation of NRI∼P (35). If this hypothesis is correct, then PII plays no direct catalytic role in the regulated phosphatase activity.

One method to obtain mutations affecting the regulated phosphatase activity is to select for spontaneous suppressors of a glnD::Tn10 mutation that result in high expression of nitrogen-regulated genes (2, 10, 34). The glnD mutation prevents the uridylylation of PII, so that the concentration of the active form of PII is greatly increased (5) and the regulated phosphatase activity is elevated, even at nitrogen-limiting conditions. The elevated phosphatase activity prevents the accumulation of NRI∼P and thus blocks expression of the Ntr regulon. Spontaneous extragenic suppressors can be obtained by demanding growth on an Ntr nitrogen source such as arginine (39). Pleiotropic mutations affecting all Ntr genes can be identified by including in the starting strain a lacZ reporter gene fusion to an unselected Ntr promoter and checking the suppressed strains for expression of the reporter on nitrogen-rich medium containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (34). Furthermore, very high expression of the Ntr regulon leads to nac-mediated inhibition of cell growth, since the Ntr-controlled Nac protein represses the synthesis of serine, glycine, and one-carbon units from glucose (8). Mutants can be screened for this growth inhibition mediated by high nac expression by testing cell growth on appropriately supplemented or unsupplemented minimal medium.

The selection and screen described above was previously exploited to obtain mutations that dramatically reduced the regulated phosphatase activity (2, 34). Mutations altering NRII were identified from the zoo by identifying strains in which suppression of glnD was lost upon introduction of a multicopy plasmid encoding wild-type NRII (2, 34). Similarly, mutations affecting PII were identified in the zoo by identifying mutants in which suppression is lost upon introduction of a plasmid overexpressing wild-type PII (2, 34). It should be noted that for certain mutations altering NRII, introduction of either of the NRII- or PII-encoding plasmid eliminated suppression (2, 34). For other mutants, suppression was eliminated by the plasmid overexpressing wild-type NRII, but DNA sequencing revealed that the strains did not contain a mutation in glnL. Here, we report on two such mutations that dramatically reduced the regulated phosphatase activity in vivo and in vitro by altering the receiver domain of NRI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteriological techniques.

The Escherichia coli strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Growth media were described previously (8, 34). Transformation of strains with plasmid DNA, preparation of phage P1 vir lysates, and generalized transductions were performed by standard techniques (40). DNA sequencing was performed by the University of Michigan DNA sequencing core facility. The PCR and sequencing primers were described previously (2, 34). β-Galactosidase assays were performed by the method of Miller (40), with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and chloroform to disrupt the cells, and the results are presented in Miller units.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid name | Relevant genotype | Construction, reference, or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| YMC10φ | Wild type, trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 4 |

| Dφ | glnD99::Tn10 trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 4 |

| Nφ | nac::CamrtrpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 8 |

| BKgφ | ΔglnB ΩGmrΔ glnK1 trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 8 |

| BKgNφ | ΔglnB ΩGmrΔ glnK1 nac::CamrtrpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 8 |

| YMC21Kφ | ΔglnALG trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 4 |

| AP1076 YMC21NKφ | ΔglnALG nac::CamrtrpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | This study |

| LPφ | ΔglnL2001 Δpta-ackA. . .zej::Tn10 trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | 4 |

| LG[glnAp2φ] | ΔglnLG trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnAp2-lac] | This study |

| AP1323 LGP[glnAp2φ] | ΔglnLG Δpta-ackA. . .zej::Tn10 trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnAp2-lac] | LG[glnAp2φ] × LPφ P1vir |

| AP1006 DG(K104Q)φ | glnD99::Tn10 glnG (K104Q) trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | Dφ→Gargtrp+ (34) |

| AP1018 DG(ΔAsp10)φ | glnD99::Tn10 glnG (ΔAsp10) trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | Dφ→Gargtrp+ (34) |

| AP1316 G(K104Q)φ | glnG (K104Q) trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | YMC21Kφ × AP1006 P1vir |

| AP1318 G(ΔAsp10)φ | glnG (ΔAsp10) trpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | YMC21Kφ × AP1018 P1vir |

| AP1308 G(K104Q)Nφ | glnG (K104Q) nac::CamrtrpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | AP1076 × AP1006 P1vir |

| AP1310 G(ΔAsp10)Nφ | glnG (ΔAsp10) nac::CamrtrpDC700::putPA1303[Kanr CamsglnKp-lac] | AP1076 × AP1018 P1vir |

| BL21 (DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm(DE3) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR322 | Medium-copy-number cloning vector, Ampr Tetr | Cloning vector |

| pACYC184 | Low-copy-number cloning vector, Camr Tetr | Cloning vector |

| pACYC184-glnL | glnLp and glnL in pACYC184, Camr Tets | 3 |

| pAP169 pgln31wt | glnG in pBR322, Ampr Tets | This study |

| pAP171 pgln31ΔAsp10 | glnG (ΔAsp10) in pBR322, Ampr Tets | This study |

| pAP170 pgln31K104Q | glnG (K104Q) in pBR322, Ampr Tets | This study |

| pET21a | High-copy-number protein expression vector, Ampr | Novagen |

| pAP161 pET21a/NRI-N | Overexpression of NRI-N (1-124)-His6, Ampr | This study |

| pAP162 pET21a/NRI-N (ΔAsp10) | Overexpression of ΔAsp10 NRI-N (1-124)-His6, Ampr | This study |

| pAP163 pET21a/NRI-N (K104Q) | overexpression of K104Q NRI-N (1-124)-His6, Ampr | This study |

Plasmid constructions.

DNA manipulations were done by standard techniques (26). Plasmids for low-level expression of NRI were designed to be similar to the pgln31 plasmid (6) and were constructed as follows. The ≈2-kbp DNA fragment extending from the unique SalI restriction enzyme site in glnL to a point approximately 150 bp past the end of the glnG stop codon was PCR amplified from genomic DNA of the appropriate strain with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). Genomic DNA was prepared with the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's directions. The PCR primers used were pgln31us (5′-CGAAATCTGGTCGACCGTCTGTTGGGG-3′) and pgln31ds (5′-AATTACTGGAATTCTGCGCCACTCGATACCAG-3′), which added an EcoRI restriction enzyme site after the glnG gene. To create plasmids pAP169 and pAP170 (Table 1), the PCR products were digested with SalI and EcoRI and ligated into similarly digested pBR322. Since the ΔAsp10 mutation creates a new SalI site in glnG, plasmid pAP171 (Table 1) was constructed by a three-way ligation of the SalI-EcoRI pBR322 fragment with the SalI-SalI and SalI-EcoRI fragments resulting from SalI and EcoRI digestion of the PCR product.

Plasmids for overexpression of the N-terminal receiver domain of NRI (amino acids 1 to 124) with a C-terminal (His)6 tag were constructed as follows. The DNA region of interest was PCR amplified from genomic DNA with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). The upstream PCR primer NRI-Nus (5′-AACGCAGTCATATGCAACGAGGGATAGTCTGG-3) added an NdeI restriction enzyme site overlapping the glnG ATG start codon. The downstream PCR primer NRI-Nds (5′-GGTTACTGCTCGAGTTCCTGGTAATGACTGATAGC-3′) added an XhoI restriction site after codon 124. The PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into similarly digested pET21a. The resulting plasmids, pAP161, pAP162, and pAP163 (Table 1), encode the N-terminal receiver domain of NRI with the additional sequence Leu-Glu-(His)6 at the C terminus. All plasmids constructed in this work were sequenced over the entire insert region to ensure that the proper sequence was present.

Purified proteins.

The preparations of PII, NRII, MBP-CT111 (amino acids 111 to 349 of NRII fused to the C terminus of maltose-binding protein[MBP]), MBP-CT126 (amino acids 126 to 349 of NRII fused to MBP), and NRII (S227R/Y302N) used in this work were described previously (16, 20, 33-35). His6-tagged wild-type NRI-N, ΔAsp10 NRI-N, and K104Q NRI-N were purified as follows. Strain E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with the appropriate plasmid, with selection for ampicillin resistance. A 350-ml LB-ampicillin seed culture was grown at 30°C overnight. The next morning, the seed culture was used to inoculate 3.5 liters of LB-ampicillin medium. The cells were grown to mid-log phase at 37°C, and protein expression was induced for 4 h by addition of 0.4 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the cell paste was stored at −80°C. Overexpression of the proteins was sufficient to allow the course of the purification to be followed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). All steps of the protein purification were carried out at 4°C and were the same for the wild-type, ΔAsp10, and K104Q proteins.

The cell paste was resuspended in TGK buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 200 mM KCl] plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and sonicated to break open cells. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatant was loaded directly on a 25-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) column equilibrated in the same buffer. The column was washed with TGK buffer plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and eluted with a linear gradient of TGK buffer plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol to TGK buffer plus 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol plus 250 mM imidazole. Peak fractions containing NRI-N were pooled, and solid ammonium sulfate was added to 55% saturation. The precipitated NRI-N was collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended in TGD buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol]. The resulting solution was loaded on a 500-ml Sephadex G-75 (Pharmacia) gel filtration column equilibrated in TGK buffer plus 1 mM dithiothreitol. The column was eluted in the same buffer. Peak fractions containing NRI-N were pooled, and solid ammonium sulfate was added to 55% saturation. The precipitated NRI-N was collected by centrifugation, resuspended in TGD buffer, dialyzed against storage buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol], and stored as aliquots at −80°C. The proteins were >95% pure as judged by visualization of Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Typical yields were ≈150 mg of protein from 3.85 liters of starting culture. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (9) and are stated in terms of the trimer for PII, the dimer for NRII, and the monomer for NRI-N. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was done by standard techniques (41).

Preparation of 32P-labeled NRI-N∼P, phosphatase assay, and kinase assay.

The MBP-CT111 protein, consisting of maltose-binding protein fused to the transmitter module of NRII, was used as the kinase for phosphorylating NRI-N (35). The MBP-CT111 protein lacks phosphatase activity, even in the presence of excess PII (16, 19). A reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP, 50 μM NRI-N, and 0.50 μM MBP-CT111 was incubated at room temperature (≈22°C) for 1 h to permit phosphorylation of the NRI-N. The reaction mixture was passed over a PD10 desalting column (Amersham-Pharmacia) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-10% (vol/vol) glycerol-100 mM KCl-2 mM EDTA-1 mM dithiothreitol to separate the NRI-N from nucleotides and Mg2+. The peak fractions containing [32P]NRI-N∼P were stored at −20°C until use. This method does not separate the phosphorylated NRI-N from unphosphorylated NRI-N or MBP-CT111.

Phosphatase assays were done as described previously (35). The data were fit to an exponential equation to determine rates of dephosphorylation. The equation t1/2 = ln 2/k, where k is the rate of dephosphorylation, provided the half-life value. The phosphorylation of the NRI-N proteins was assayed as described previously (31, 34, 35, 47) by measuring the incorporation of 32P into trichloroacetic acid-precipitable material. The stability of phosphoryl groups in an acid or base was determined as follows. A phosphorylation assay similar to the one shown in Fig. 3 was conducted, and aliquots of the reaction mixtures were spotted onto nitrocellulose filters in duplicate. One set of filters was washed in 5% trichloroacetic acid (pH ≈1 to 2) for 70 min, and the other was washed in 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH ≈11 to 12) for 70 min. The 32P-labeled phosphate remaining in the denatured NRI-N proteins was determined by liquid scintillation counting of the dried filters.

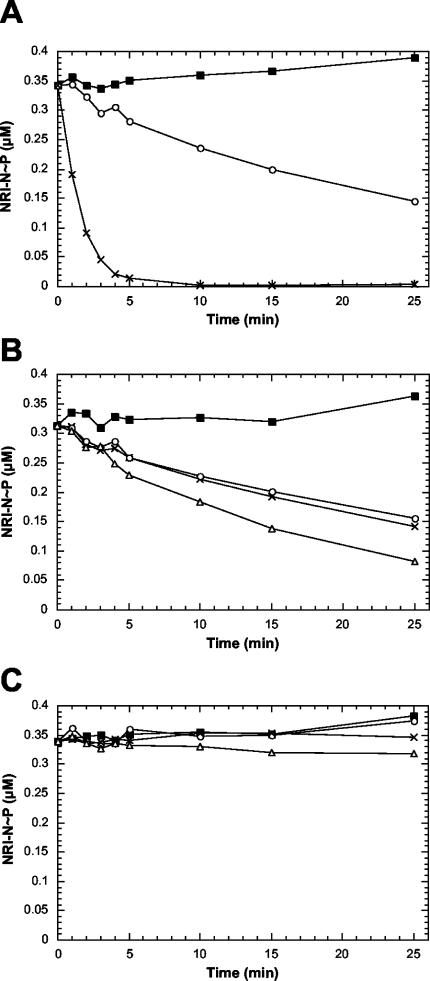

FIG. 3.

Phosphorylation of the wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins by NRII in the absence and presence of PII. Wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins were assayed for their ability to be phosphorylated in the presence of NRII and dephosphorylated in the presence of NRII and PII. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C and contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mg of bovine serum albumin v, 50 μM 2-ketoglutarate, 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP, 0.3 μM NRII, and 30 μM wild-type or altered NRI-N protein in the absence or presence of 0.3 μM PII. At the indicated times, aliquots of the reaction mixtures were removed and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: ○, wild-type NRI-N, no PII; •, wild-type NRI-N, + PII; Δ, ΔAsp10 NRI-N, no PII; ▴, ΔAsp10 NRI-N, + PII; □, K104Q NRI-N, no PII; ▪, K104Q NRI-N, + PII.

RESULTS

Identification of spontaneous extragenic suppressors of glnD99::Tn10 that map to glnG and encode altered NRI proteins.

Mutation of glnD results in an increase in the concentration of the unmodified form of PII, which interacts with NRII to bring about regulated phosphatase activity. The elevated phosphatase activity in a glnD mutant prevents activation of the Ntr regulon and the utilization of certain poor nitrogen sources as the sole source of nitrogen. In a previous study, we isolated numerous spontaneous suppressors of glnD that restored the ability to use arginine as the sole nitrogen source (34). Two suppressed strains were particularly interesting, as they showed dramatically elevated Ntr gene expression on nitrogen-rich medium, and suppression was eliminated by introduction of a multicopy plasmid expressing wild-type NRII, yet the strains did not contain a mutation in glnL (34). One of the mutant strains, AP1006, displayed very poor growth on nitrogen-rich minimal medium that was eliminated upon supplementation of the medium with amino acids, similar to the growth properties displayed by Ntr constitutive strains that highly express Nac. The other mutant, AP1018, grew only slightly worse than the wild type on nitrogen-rich minimal medium lacking amino acid supplementation.

We determined the DNA sequences of the glnL and glnG genes of strains AP1006 and AP1018 and observed that each of the strains contained a wild-type glnL allele and a mutant glnG allele. Strain AP1018 contained a deletion of codon 10 (GAT) of glnG, resulting in the deletion of aspartate 10 of the protein. Strain AP1006 contained a single base alteration (AAA → CAA) in codon 104 of glnG, resulting in the conversion of lysine 104 to glutamine. These mutations altered highly conserved residues within the receiver domain of NRI that are close to the active-site aspartate 54 (14). For convenience, we will refer to the mutant alleles by the alterations that they caused.

To facilitate in vivo analysis of the mutant glnG alleles, we built strains containing the mutant alleles, a wild-type glnD gene, and a single-copy glnKp-lacZYA fusion (referred to as Gφ strains, Table 1). We also built an isogenic set of strains containing in addition a null mutation in nac (referred to as GNφ strains, Table 1). Comparison of the growth of the isogenic nac+ and nac strains on nitrogen-rich minimal medium gives an indication of the degree of expression of the Ntr regulon. One of the mutant glnG alleles, encoding K104Q, resulted in dramatic nac-dependent growth inhibition on nitrogen-rich minimal medium (Fig. 1). The other mutant glnG allele, encoding ΔD10, caused a much weaker nac-dependent growth inhibition (data not shown), suggesting that higher Ntr expression resulted from the K104Q mutation than from the ΔD10 mutation.

FIG. 1.

Poor growth phenotype imparted by the glnG K104Q allele. The strains were grown on solid glucose-ammonia-glutamine-tryptophan minimal medium for 42 h at 37°C. The strains were as follows, with the relevant genotype given in brackets: 1, YMC10φ [wild type]; 2, BKgφ [ΔglnB ΩGmr ΔglnK1]; 3, G(K104Q)φ [glnG (K104Q)]; 4, Nφ [nac::Camr]; 5, BKgNφ [ΔglnB ΩGmr ΔglnK1 nac::Camr]; 6, G(K104Q)Nφ [glnG (K104Q) nac::Camr].

The GNφ strains, which displayed normal growth on minimal medium, were used to measure the regulation of the Ntr-controlled glnK promoter (Table 2). In the wild-type strain as well as in a nac mutant, the glnK promoter was inactive when cells were grown on nitrogen-rich medium containing both ammonia and glutamine as nitrogen sources and partially active when the cells were grown on nitrogen-limiting medium with glutamine as the sole nitrogen source (Table 2), as expected (4, 8). In contrast, very high expression of the glnK promoter was obtained in cells that lacked both PII and the PII paralogue GlnK and thus lacked the ability to activate the phosphatase activity, as expected (4, 8) (Table 1). Interestingly, in this strain the presence of ammonia consistently resulted in lower expression of the glnK promoter than was observed in the absence of ammonia (≈30% lower). This difference is currently unexplained and may be due to reduced acetyl phosphate accumulation in the presence of ammonia (4, 12). Both of the glnG mutations (ΔD10 and K104Q) resulted in dramatically elevated expression of the glnK promoter on medium containing ammonia (Table 2). The K104Q mutation resulted in glnK promoter expression that was about 69% of the level seen in cells lacking the regulated phosphatase, while the ΔD10 mutation resulted in glnK promoter expression that was about 23% that seen in cells lacking the regulated phosphatase activity. Both mutations also resulted in elevated glnK promoter activity, relative to the wild type, on nitrogen-limiting medium, although again the effects of the K104Q mutation were more dramatic (Table 2). These results are consistent with the observation that the K104Q mutation but not the ΔD10 mutation resulted in nac-mediated growth inhibition on minimal medium and show that the Ntr regulon is expressed at a very high level in cells containing the K104Q mutation.

TABLE 2.

Effect of mutant glnG alleles on expression of the nitrogen-regulated glnK promoter under nitrogen-limiting and nitrogen-replete conditions

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | β-Galactosidase activityb (Miller units)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gglntrp | GNglntrp | ||

| YMC10φ | Wild type | 780 | 0 |

| Nφ | nac::camr | 670 | 0 |

| BKgNφ | ΔglnB ΩGmr ΔglnK1 nac::camr | 3,780 | 2,510 |

| G(ΔAsp10)Nφ | glnG (ΔAsp10) nac::camr | 1,120 | 580 |

| G(K104Q)Nφ | glnG (K104Q) nac::camr | 2,400 | 1,730 |

In addition to the genotypes shown, all strains contained trpDC700::putPA1303 [kanrglnKp-lac], which is a fusion of the lacZYA operon to the nitrogen-regulated glnK promoter (4).

β-Galactosidase activity values are stated in Miller units and are the averages of duplicate cultures. Results from duplicate cultures differed by <10%. Cultures were grown overnight in the indicated medium, diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.02, and grown at 37°C to an optical density of 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.6. The media used were Gglntrp, (glucose-glutamine-tryptopham) GNglntrp (glucose-ammonia-glutamine-tryptophan). Glucose was present at 0.4%, ammonia (as ammonium sulfate) and glutamine were present at 0.2%, and tryptophan was present at 0.04 mg/ml. In addition, media contained thiamine at 0.004% and kanamycin at 50 μg/ml.

Previous studies have described altered NRI proteins that activate expression of Ntr genes in the absence of phosphorylation or appear to do so because they are much more potent as transcriptional activators when phosphorylated at a low “basal” level (13, 46). To test these possibilities, we examined the activation of a single-copy glnA promoter-lacZ fusion in cells containing either a chromosomal deletion of glnL-glnG or deletions of both glnL-glnG and the pta-ackA region of the chromosome. Deletion of glnL-glnG eliminates both NRII and NRI, while deletion of the pta-ackA region of the chromosome eliminates the capacity to form acetyl phosphate. The ability of the wild-type glnG allele and the K104Q and ΔD10 mutant glnG alleles to bring about activation of the glnA promoter was assessed by introducing the glnG alleles on multicopy plasmids that program low expression of the protein, as described in Materials and Methods.

We observed that the wild-type glnG allele behaved as expected (12); it was able to activate the glnA promoter in cells lacking NRII, but only if the capacity to make acetyl phosphate was present (data not shown). In contrast, both mutant glnG alleles (K104Q and ΔD10) were unable to drive glnA promoter expression in cells lacking NRII even when the capacity to form acetyl phosphate was present (data not shown). Introduction of a compatible low-copy-number plasmid that expressed wild-type NRII restored the ability of the mutant glnG alleles to drive glnA promoter expression (data not shown). These results suggested that the altered NRI proteins required phosphorylation for activity in intact cells and furthermore that they were defective in using acetyl phosphate as a source of phosphoryl groups and thus required NRII for activity.

Properties of the purified K104Q and ΔD10 receiver domains.

We constructed plasmids that overexpressed the wild-type, ΔD10, and K104Q N-terminal receiver domains [NRI-N, amino acids 1 to 124 with a C-terminal (His)6 tag], and purified these domains to greater than 95% purity. All three versions of the receiver domain eluted from a gel filtration column at a volume indicating that they were monomeric (data not shown).

To directly assess the autophosphatase activities of the receiver domains and their ability to be dephosphorylated by the NRII-PII complex, we used a previously described assay (16, 19, 34). We phosphorylated the receiver domains with a fusion protein consisting of MBP linked to the transmitter module of NRII (MBP-CT111). Previous studies with this fusion protein indicated that it was able to phosphorylate NRI-N but lacked phosphatase activity even in the presence of excess PII (16, 19). After labeling of the receiver domains, the phosphoryl groups were stabilized with EDTA, and labeled ATP and Mg2+ were removed with a short gel filtration column. The stability of the phosphorylated receiver domains was then determined directly under various conditions.

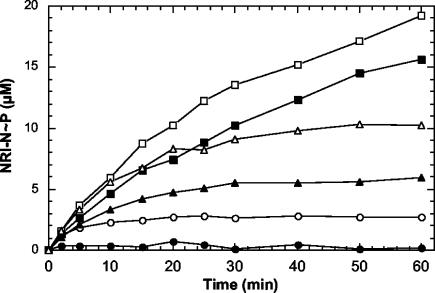

For all three phosphorylated receiver domains, the phosphoryl groups were stable over the time course of our experiments in the absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 2). Upon addition of excess Mg2+, the wild-type and ΔD10 receiver domains displayed similar autophosphatase activities, while the K104Q receiver domain seemed to completely lack the autophosphatase activity (Fig. 2). The autophosphatase activity of the wild-type and ΔD10 receiver domains measured here (t1/2 of ≈20 min at 25°C) was slightly slower than observed in previous studies, which may reflect our use of a slightly longer receiver domain (residues 1 to 124).

FIG.2.

Dephosphorylation of phosphorylated wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins. The stability of the phosphorylated wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins was examined in the presence of magnesium or in the presence of magnesium, PII, and NRII. The 32P-labeled NRI-N≈P substrates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The dephosphorylation reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C and contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, 0.3 mg of bovine serum albumin, 0.5 mM AMP-PNP, 50 μM 2-ketoglutarate, and 0.49 μM [32P]NRI-N≈P with the following additions: (▪) buffer; (○) 10 mM MgCl2; (×) 10 mM MgCl2, 2 μM PII, and 15 nM NRII; and (Δ) 10 mM MgCl2, 2 μM PII, and 150 nM NRII. At the indicated times, aliquots of the reaction mixtures were removed and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Wild-type NRI-N≈P; (B) ΔAsp10 NRI-N≈P; (C) K104Q NRI-N≈P.

To assay the regulated phosphatase activity, we examined the effect of adding PII in excess and a low concentration of NRII (15 nM) under conditions in which PII is very effective in stimulating the dephosphorylation of NRI-N∼P and the autophosphorylation of NRII cannot occur. The wild-type receiver domain was rapidly dephosphorylated under these conditions (Fig. 2A), as expected. In contrast, the ΔD10 receiver domain was dephosphorylated at a rate similar to that observed in the absence of NRII, that is, it was resistant to the regulated phosphatase activity (Fig. 2B). When the concentration of NRII was raised 10-fold (to 150 nM), the rate of dephosphorylation of the ΔD10 receiver was increased slightly, suggesting that it retained a residual ability to be dephosphorylated by the NRII-PII complex (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the K104Q receiver domain appeared to be completely resistant to dephosphorylation by the NRII-PII complex (Fig. 2C). These results show that the K104Q alteration eliminated both the autophosphatase activity and the regulated phosphatase activity, while the ΔD10 alteration had little effect on the autophosphatase activity but effectively blocked the regulated phosphatase activity.

To assess the phosphorylation of the receiver domains by NRII, we used a method described previously (16, 31, 35). The receiver domain, in excess, was phosphorylated by NRII (with and without PII) in the presence of labeled ATP. In this assay, the final steady-state level of NRI-N phosphorylation reflects the balance between its phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (16). In reaction mixtures containing 30 μM wild-type NRI-N, 0.3 μM NRII, and no PII, approximately 7% of the available NRI-N was phosphorylated at the steady state (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, when PII was added to 0.3 μM, a barely detectable level of wild-type NRI-N phosphorylation was observed, as expected (Fig. 3). This is because under the conditions used, PII both inhibits the autophosphorylation of NRII and activates the regulated phosphatase activity (17).

Under the same experimental conditions, approximately 33% of the ΔD10 NRI-N protein was phosphorylated at the steady state in the absence of PII, while a somewhat lower level of phosphorylation was obtained in the presence of PII (Fig. 3). For the K104Q NRI-N protein, a steady-state level of phosphorylation was not yet attained after 1 h, at which point approximately 63% of the total K104Q NRI-N was phosphorylated in the absence of PII. In the presence of PII, the K104Q phosphorylation level was decreased slightly (Fig. 3). Since both of these mutant proteins were resistant to the regulated phosphatase activity in the direct assay (Fig. 2), the reduced steady-state levels of phosphorylation observed in the presence of PII may reflect the effect of PII in reducing NRII autophosphorylation. The ΔD10 and K104Q receiver domains did not seem to have any defect in their ability to accept phosphoryl groups from NRII (Fig. 3). Note that even in the presence of PII, the steady-state levels of phosphorylation of the altered receiver domains were significantly higher than that of the wild type in the absence of PII, consistent with the phenotypes of the mutant strains. Curiously, the phosphorylation of the K104Q protein appeared to be biphasic, with an initial rate sustained for about 30 min and a slower rate thereafter. This is hardly discernible in Fig. 3, but the phenomenon was more pronounced when a higher NRII concentration was used and when the assay was conducted at 37°C instead of 25°C (data not shown).

The altered NRI-N proteins are probably phosphorylated on aspartate. For all three versions of the receiver domain, the phosphoryl groups were stable in an acid environment and highly unstable in a basic environment (Materials and Methods), as expected (data not shown).

NRII exhibits significant basal phosphatase activity in the absence of PII.

The results in Fig. 3 showed that the ΔD10 NRI-N protein exhibited a higher level of phosphorylation than did wild-type NRI-N when they were phosphorylated by NRII in the absence of PII. Since the ΔD10 receiver domain displayed normal autophosphatase activity (Fig. 2), we considered the possibilities that wild-type NRII exhibited significant PII-independent basal phosphatase activity and that the resistance of the ΔD10 receiver domain to this activity contributed to its elevated phosphorylation. A previous study with purified components demonstrated that a mutant form of NRII, NRII-I141V, exhibited weak PII-independent basal phosphatase activity in a dephosphorylation assay similar to the one described here (16, 35), Also, NRII-H139N displays weak phosphatase activity in the absence of PII that is greatly activated by PII (16).

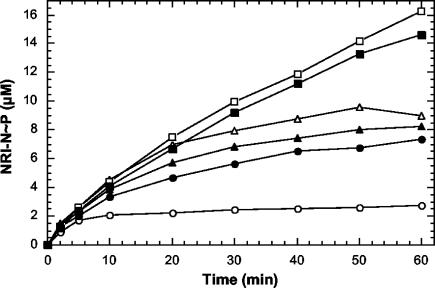

To test whether wild-type NRII had significant basal phosphatase activity in the absence of PII, we compared the ability of wild-type NRII and the doubly mutant NRII-S227R/Y302N to phosphorylate the wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins. The NRII-S227R/Y302N protein contains amino acid substitutions that alter the binding of PII (S227R) and the ATP lid (Y302N) of NRII, both of which are required for PII-activated phosphatase activity. A previous study showed that this protein completely lacked phosphatase activity (35). Also, compared to wild-type NRII, NRII-S227R/Y302N phosphorylated wild-type NRI-N to a higher extent (35); in that report, we referred to this ability as elevated kinase activity.

Consistent with our previous results, we observed elevated phosphorylation of wild-type NRI-N in the presence of NRII-S227R/Y302N (Fig. 4). In contrast, the altered NRI-N proteins appeared to be resistant to the elevated kinase activity of NRII-S227R/Y302N; that is, they were phosphorylated to similar extents by wild-type NRII and NRII-S227R/Y302N (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the elevated kinase activity of NRII-S227R/Y302N was really a lack of basal phosphatase activity. Moreover, the results suggest that NRII exhibited PII-independent basal phosphatase activity and that resistance of the altered NRI-N proteins to this activity contributed to their elevated phosphorylation in the experiments shown in Fig. 3. In additional experiments, we observed that two different phosphatase-deficient NRII proteins, MBP-CT111 and MBP-CT126 (16, 20), were both capable of phosphorylating wild-type NRI-N to approximately the same level as ΔD10 NRI-N (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation assay comparing the ability of wild-type NRII and a phosphatase-deficient NRII protein to phosphorylate the wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins. Wild-type and altered NRI-N proteins were assayed for their ability to be phosphorylated in the presence of wild-type NRII or NRII (S227R/Y302N). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C and contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP, 0.3 μM wild-type NRII or NRII (S227R/Y302N), and 30 μM wild-type or altered NRI-N protein. At the indicated times, aliquots of the reaction mixtures were removed and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: ○, wild-type NRI-N with wild-type NRII; •, wild-type NRI-N with NRII (S227R/Y302N); Δ, ΔAsp10 NRI-N with wild-type NRII; ▴, ΔAsp10 NRI-N with NRII (S227R/Y302N); □, K104Q NRI-N with wild-type NRII; ▪, K104Q NRI-N with NRII (S227R/Y302N).

DISCUSSION

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that the regulated phosphatase activity of NRII is not a distinct phosphatase activity but rather reflects collaboration of the NRII-PII complex with NRI∼P to bring about its dephosphorylation. The K104 residue is necessary for both autophosphatase and regulated phosphatase activities, perhaps because it plays a role in the structure of the phosphorylated receiver that is essential for both activities. Conversely, the D10 residue may be involved in the process by which the NRII-PII complex activates the autophosphatase activity or may be required for the binding of the PII-NRII complex to NRI∼P. The structural data for NRI-N and other receiver proteins discussed below renders this hypothesis feasible; however, alternative hypotheses have not been excluded. For example, the K104Q mutation may simultaneously eliminate the autophosphatase activity and the ability of NRI-N∼P to bind to the NRII-PII complex. To resolve this issue, it will be necessary to determine whether the phosphorylated K104Q and ΔD10 proteins are able to bind normally to the NRII-PII complex.

In a previous study, site-specific mutagenesis was used to alter lysine 104 to arginine in NRI, and the effects of the K104R substitution were assessed in intact cells (28). The K104R mutation resulted in normal expression of glnA on nitrogen-limiting medium and elevated expression of the glnA relative to the wild type in cells containing the glnD mutation (28). Although different methods were used in the earlier study (28) and our study, it seems that the K104R alteration is similar to but less severe than the K104Q alteration. The K104R protein was not examined in vitro, so direct comparisons with the K104Q protein are not possible. The phenotype resulting from the K104R alteration and prior work with CheY (see below) led to the suggestion that it was defective in dephosphorylation (28).

A CheY mutant containing a substitution of the analogous lysine residue, K109R, has been described (25). This mutation had no effect on the phosphorylation of CheY and reduced CheY∼P autophosphatase activity about fivefold. The K109R alteration also rendered CheY∼P resistant to dephosphorylation by the CheZ phosphatase (25). Its effect was similar to but less dramatic than the effect of the K104Q alteration in NRI. However, the CheY K109R protein was inactive in cells, showing that the conserved lysine in CheY is required for occupation of the active conformation that interacts with the flagellar motor (25). In contrast, the K104Q alteration in NRI was selected for its ability to activate the Ntr regulon, so we may assume that this alteration in NRI does not prevent occupation of the active conformation upon phosphorylation.

The receiver domain is a (β/α)5 structure, with a highly conserved active site consisting of residues in the loops at the C-terminal end of the β strands. The structures of the nonphosphorylated forms of several receiver domains have been determined, and several approaches have been used to obtain structural information on the phosphorylated forms of the proteins (discussed in reference 11). For example, phosphorylated receiver domains that have been depleted of metal, phosphonocysteine-containing receiver domains, and receiver domains that contain a BeF3− complex at the active site have been studied. The active site in the phosphorylated receiver consists of residues D11, D12, K104, T82, and the phosphorylated D54 (with the NRI numbering, as in reference 14). Mg2+ is chelated by D11 and D12, K104 forms a salt bridge with the phosphoryl group (or BeF3− in the NRI structure) (14), and T62 forms a hydrogen bond to the phosphoryl (BeF3−) group.

Some information is available as to how the phosphorylation of the receiver domain propagates a signal (reference 11 and citations therein). For NRI, the conformational change occurring upon phosphorylation is somewhat more extensive than for the other receiver domains studied so far. Repositioning of T82 leads to an alteration in α4, which moves Y101 from one hydrophobic pocket to another, a process referred to as T/Y switching (11). The receiver domain is structurally related to the haloacid dehalogenase superfamily, which includes P-type ATPases (11). The haloacid dehalogenase superfamily members are also phosphorylated on an aspartate residue, have conserved lysine and threonine residues arranged as in the receiver proteins, and show similar roles for these residues in the structures of their BeF3− complexes. Like the receiver proteins, the phosphoaspartate in these proteins is frequently highly unstable (i.e., they have autophosphatase activity).

Wemmer and colleagues proposed that residue H84 acts as a base to activate a water molecule that attacks the phosphoryl group (14). They note that not only is the residue suitably positioned, but receivers with high autophosphatase activity have histidine at this position, while receivers with reduced autophosphatase activity contain residues unable to act as base at this position. In contrast, the K104 residue is thought to form a salt bridge with the phosphoryl group, which should stabilize the phosphoryl group. The mechanism by which alteration of this residue further stabilizes the phosphoryl group is not obvious, and clearly structural information on the K104Q mutant would be highly desirable. There was no assignment for the K104 residue in the high-resolution BeF3− NRI-N nuclear magnetic resonance structure (14), so its position and role in NRI-N can be further defined in additional experiments.

How does the dephosphorylation reaction occur? A likely scenario is that an activated water molecule in the active site attacks the phosphoryl group. Stock and colleagues used 18O incorporation studies and other methods to show that 18O is not associated with the CheY protein after hydrolysis, effectively excluding another possible mechanism (49). In the case of the chemotaxis system, the CheZ phosphatase acts by a mechanism that is intermediate between allosteric activation and direct catalysis (51). The 2.9-Å crystal structure of the CheZ-CheY(BeF3−) complex shows that CheZ inserts Q147 into the active site of CheY, where it interacts with and positions CheY residue N59, which in turn is thought to activate a water molecule for attack on the phosphoryl group. In addition, CheZ D143 interacts with CheY K109. Thus, CheZ contributes to and reorganizes the active site in a way that favors hydrolysis of the phosphoryl group (51).

As noted in reference 51, the mechanism of CheZ-mediated dephosphorylation is reminiscent of the eukaryotic GAP signal transduction proteins that stimulate the GTPase activity of Ras by contributing an arginine side chain to the active site with a role similar to that of CheZ Q147. Furthermore, as noted in reference 51, the complex of CheZ and CheY is reminiscent of the Spo0B-Spo0F complex, mediating phosphotransfer in the phosphorelay system controlling sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (50). Structural information for the Spo0B protein (45, 50) and the EnvZ transmitter protein Dhp domain (44) suggests that the Spo0B-Spo0F interaction should be highly similar to the two-component systems' transmitter-receiver interaction. Based on these results from related systems, it is tempting to speculate that in the NRI∼P-NRII interaction, the Dhp domain of NRII may act in a similar fashion to CheZ to position a residue of NRI that activates a water molecule at the active site while at the same time interacting with and repositioning K104.

If the above hypothesis is true, then the role of PII in regulated phosphatase activity is to control the conformation of NRII so that the Dhp domain may adopt the conformation that brings about dephosphorylation of NRI-N∼P. It is intriguing that CheZ has a bipartite interaction with CheY (51) and that, in NRII, both the Dhp domain and the opposing ATP lid are required for potent phosphatase activity (35). PII binding to one of the C-terminal domains of NRII may orient these two surfaces (ATP lid and Dhp) for productive interaction with NRI-N∼P. The observations here and previously that various versions of NRII have basal “phosphatase” activity in the absence of PII are consistent with the hypothesis that PII plays no direct role in catalysis and show that NRII can occasionally occupy the active conformation in the absence of PII.

The role of the D10 residue is unresolved, and analogous alterations in other receivers have not been described. In NRI-N, the residues at positions 10 to 13 are all aspartates. Sequence alignments of the receiver proteins suggest that residues D10 and D11 correspond to the highly conserved aspartates found in other receiver proteins, which chelate Mg2+. However, structural information indicated that, in the receiver domain of NRI, residues D11 and D12 form part of the active site and chelate Mg2+ (14). Given its proximity to residues D11 and D12, deletion of D10 could alter metal binding. However, the ΔD10 protein was readily phosphorylated and had normal autophosphatase activity, suggesting that the active site was not greatly perturbed. The alteration of site D11 in NRI (28) and sites analogous to D11 and D12 in the CheY protein (25) resulted in a quite different phenotype; the altered proteins were dramatically defective in phosphorylation in vitro and inactive in vivo. The ΔD10 alteration may block the binding of the PII-NRII complex or may render this binding ineffective by moving the target or otherwise preventing the interactions in the active site needed for the activation of water.

Since numerous two-component system transmitter proteins display “phosphatase” activity (reviewed in reference 48), it is reasonable to speculate that this common activity proceeds by a similar mechanism. Thus, it seems likely that the “phosphatase” activity of the two-component systems' transmitter proteins is not an independent activity but reflects collaboration between the transmitter and phosphorylated receiver proteins. It is ironic that neither of the two activities initially attributed to the transmitter protein, kinase and phosphatase activities (31), are independent activities in the classical sense. Instead, the receiver catalyzes its own phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, and the transmitter protein serves as the substrate in the former case and as an activator in the latter case.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM59637.

We thank Boris Magasanik for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson, M. R., T. A. Blauwkamp, V. Bondarenko, V. Studitsky, and A. J. Ninfa. 2002. Activation of the glnA, glnK, and nac promoters as Escherichia coli undergoes the transition from nitrogen-excess growth to nitrogen starvation. J. Bacteriol. 184:5358-5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, M. R., and A. J. Ninfa. 1992. Characterization of Escherichia coli mutations affecting nitrogen regulation. J. Bacteriol. 174:4538-4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson, M. R., and A. J. Ninfa. 1993. Mutational analysis of the bacterial signal-transducing protein kinase/phosphatase nitrogen regulator II (NRII or NtrB). J. Bacteriol. 175:7016-7023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson, M. R., and A. J. Ninfa. 1998. Role of the GlnK signal transduction protein in the regulation of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 29:431-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson, M. R., E. S. Kamberov, R. L. Weiss, and A. J. Ninfa. 1994. Reversible uridylylation of the Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein regulates its ability to stimulate the dephosphorylation of the transcription factor Nitrogen Regulator I (NRI or NtrC). J. Biol. Chem. 269:28288-28293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backman, K., Y.-M. Chen, S. Ueno-Nishio, and B. Magasanik. 1983. The product of glnL is not essential for the regulation of bacterial nitrogen assimilation. J. Bacteriol. 154:516-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilwes, A. M., L. A. Alex, B. R. Crane, and M. I. Simon. 1999. Structure of CheA, a signal transducing histidine kinase. Cell 96:131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blauwkamp, T. A., and A. J. Ninfa. 2002. Nac-mediated repression of the serA promoter of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:351-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein using the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bueno, R., G. Pahel, and B. Magasanik. 1985. Role of glnB and glnD gene products in the regulation of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 164:816-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho, H. S., J. G. Pelton, D. Yan, S. Kustu, and D. E. Wemmer. 2001. Phosphoaspartates in bacterial signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:679-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, J., M. R. Atkinson, W. McCleary, J. B. Stock, B. L. Wanner, and A. J. Ninfa. 1992. Role of phosphorylated metabolic intermediates in the regulation of glutamine synthetase synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174:6061-6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flashner, Y., D. S. Weiss, J. Keener, and S. Kustu. 1995. Constitutive forms of the enhancer-binding protein NtrC: evidence that essential oligomerization determinants lie in the central activation domain. J. Mol. Biol. 249:700-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings, C. A., S.-Y. Lee, H. S. Cho, D. Yan, S. Kustu, and D. E. Wemmer. 2003. High-resolution solution structure of the beryllofluoride-activated NtrC receiver domain. Biochemistry 42:9081-9090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess, J. F., R. B. Bourret, and M. I. Simon. 1988. Histidine phosphorylation and phosphoryl group transfer in bacterial chemotaxis. Nature 336:139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang, P., M. R. Atkinson, C. Srisawat, Q. Sun, and A. J. Ninfa. 2000. Functional dissection of the dimerization and enzymatic activities of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II and their regulation by the PII protein. Biochemistry 39:13433-13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, P., and A. J. Ninfa. 1999. Regulation of the autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli NRII by the PII signal transduction protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:1906-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang, P., and A. J. Ninfa. 2000. Asymmetry in the autophosphorylation of the two-component systems transmitter protein NRII (NtrB) of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 39:5058-5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamberov, E. S., M. R. Atkinson, P. Chandran, and A. J. Ninfa. 1994. Effect of mutations in Escherichia coli glnL (ntrB), encoding nitrogen regulator II (NRII or NtrB), on the phosphatase activity involved in bacterial nitrogen regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28294-28299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamberov, E. S., M. R. Atkinson, P. Chandran, J. Feng, and A. J. Ninfa. 1994. Signal transduction components controlling bacterial nitrogen assimilation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 40:175-191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keener, J., and S. Kustu. 1988. Protein kinase and phosphoprotein phosphatase activities of nitrogen regulatory proteins NTRB and NTRC of enteric bacteria: Roles of the conserved amino-terminal domain of NTRC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:4976-4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer, G., and V. Weiss. 1999. Functional dissection of the transmitter module of the histidine kinase NtrB in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:604-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, S.-Y., A. De La Torre, D. Yan, S. Kustu, B. T. Nixon, and D. E. Wemmer. 2003. Regulation of the transcriptional; activator NtrC1: structural studies of the regulatory and AAA+ ATPase domains. Genes Dev. 17:2552-2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukat, G. S., W. R. McCleary, A. M. Stock, and J. B. Stock. 1992. Phosphorylation of bacterial response regulator proteins by low molecular weight phospho-donors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:718-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukat, G. S., B. H. Lee, J. M. Mottonen, A. M. Stock, and J. B. Stock. 1991. Roles of highly conserved aspartate and lysine residues in the response regulator of bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8348-8354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Marina, A., C. Mott, A. Auyzenberg, W. A. Hendrickson, and C. D. Waldburger. 2001. Structural and mutational analysis of the PhoQ histidine kinase catalytic domain: insight into the reaction mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 276:41182-41190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore, J. B., S.-P. Shiau, and L. J. Reitzer. 1993. Alterations of highly conserved residues in the regulatory domain of nitrogen regulator I (NtrC) of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:2692-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ninfa, A. J., and R. L. Bennett. 1991. Identification of the site of autophosphorylation of the bacterial protein kinase/phosphatase NRII. J. Biol. Chem. 266:6888-6893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ninfa, A. J., P. Jiang, M. R. Atkinson, and J. A. Peliska. 2000. Integration of antagonistic signals in the regulation of bacterial nitrogen assimilation. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 36:32-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ninfa, A. J., and B. Magasanik. 1986. Covalent modification of the glnG product, NRI, by the glnL product, NRII, regulates the transcription of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:5909-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ninfa, E. G., M. R. Atkinson, E. S. Kamberov, and A. J. Ninfa. 1993. Mechanism of autophosphorylation of Escherichia coli nitrogen regulator II (NRII or NtrB): trans-phosphorylation between subunits. J. Bacteriol. 175:7024-7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pioszak, A. A., P. Jiang, and A. J. Ninfa. 2000. The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein regulates the activities of the two-component system transmitter protein NRII by direct interaction with the kinase domain of the transmitter module. Biochemistry 39:13450-13461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pioszak, A. A., and A. J. Ninfa. 2003. Genetic and biochemical analysis of phosphatase activity of Escherichia coli NRII (NtrB) and its regulation by the PII signal transduction protein. J. Bacteriol. 185:1299-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pioszak, A. A., and A. J. Ninfa. 2003. Mechanism of the PII-activated phosphatase activity of Escherichia coli NRII (NtrB): how the different domains of NRII collaboreate to act as a phosphatase. Biochemistry 42:8885-8899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popham, D. L., D. Szeto, J. Keener, and S. Kustu. 1989. Function of a bacterial activator protein that binds to transcriptional enhancers. Science 243:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saiki, R. K. 1990. Amplification of genomic DNA. p. 13-20 In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sinsky, and T. J. White (ed.) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 38.Sanders, D. A., B. L. Gillece-Castro, A. L. Burlingame, and D. E. Koshland, Jr. 1992. Phosphorylation site of NtrC, a protein phosphatase whose covalent intermediate activates transcription. J. Bacteriol. 174:5117-5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider, B. L., A. K. Kiupakis, and L. J. Reitzer. 1998. Arginine catabolism and the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:4278-4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Smith, B. J. 1984. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of proteins, p. 41-56. In J. M. Walker (ed.), Methods in molecular biology, vol. 1: proteins. Humana Press, Clifton, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song, Y., D. Peisach, A. A. Pioszak, and A. J. Ninfa. 2004. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of the two-component systems transmitter protein NRII (NtrB), regulator of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 43:6670-6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka, T., S. K. Saha, C. Timomori, R. Ishima, D. Liu, K. I. Tong, H. Park, R. Dutta, L. Qin, M. B. Swindells, T. Yamazaki, A., M. Ono, M. Kainosho, M. Inouye, and M. Ikura. 1998. NMR structure of the histidine kinase domain of the E. coli osmosensor EnvZ. Nature 396:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomomori, C., T. Tanaka, R. Dutta, H. Park, S. K. Saha, Y. Zhu, R. Ishima, D. Liu, K. I. Tong, H. Kurokawa, H. Qian, M. Inouye, and M. Ikura. 1999. Solution structure of the homodimeric core domain of Escherichia coli histidine kinase EnvZ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:729-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varughese, K. I., Madhusudan, X. Z. Zhou, J. M. Whiteley, and J. A. Hoch. 1998. Formation of a novel four helix bundle and molecular recognition sites by dimeriozation of a response regulator phosphotransferase. Mol. Cell 2:485-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weglensky, P., A. J. Ninfa, S. Ueno-Nishio, and B. Magasanik. 1989. Mutations in the glnG gene of Escherichia coli resulting in increased activity of nitrogen regulator I. J. Bacteriol. 171:4479-4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss, V., and B. Magasanik. 1988. Phosphorylation of nitrogen regulator I (NRI) of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8519-8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West, A. H., and A. M. Stock. 2001. Histidine kinase and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:369-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolanin, P. M., D. J. Webre, and J. B. Stock. 2003. Mechanism of phosphatase activity in the chemotaxis response regulator CheY. Biochemistry 42:14075-14082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zapf, J., U. Sen, Madhusudan, J. A. Hoch, and K. I. Varughese. 2000. A transient interaction between two phosphorelay proteins trapped in a crystal lattice reveals the mechanism of molecular recognition and phosphotransfer in signal transduction. Structure 6:851-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao, R., E. J. Collins, R. B. Bourret, and R. E. Silversmith. 2002. Structure and catalytic mechanism of the E. coli chemotaxis phosphatase CheZ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:570-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]