Abstract

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptional regulator AlgR controls a variety of different processes, including alginate production, type IV pilus function, and virulence, indicating that AlgR plays a pivotal role in the regulation of gene expression. In order to characterize the AlgR regulon, Pseudomonas Affymetrix GeneChips were used to generate the transcriptional profiles of (i) P. aeruginosa PAO1 versus its algR mutant in mid-logarithmic phase, (ii) P. aeruginosa PAO1 versus its algR mutant in stationary growth phase, and (iii) PAO1 versus PAO1 harboring an algR overexpression plasmid. Expression analysis revealed that, during mid-logarithmic growth, AlgR activated the expression of 58 genes while it repressed the expression of 37 others, while during stationary phase, it activated expression of 45 genes and repression of 14 genes. Confirmatory experiments were performed on two genes found to be AlgR repressed (hcnA and PA1557) and one AlgR-activated operon (fimU-pilVWXY1Y2). An S1 nuclease protection assay demonstrated that AlgR repressed both known hcnA promoters in PAO1. Additionally, direct measurement of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production showed that P. aeruginosa PAO1 produced threefold-less HCN than did its algR deletion strain. AlgR also repressed transcription of two promoters of the uncharacterized open reading frame PA1557. Further, the twitching motility defect of an algR mutant was complemented by the fimTU-pilVWXY1Y2E operon, thus identifying the AlgR-controlled genes responsible for this defect in an algR mutant. This study identified four new roles for AlgR: (i) AlgR can repress gene transcription, (ii) AlgR activates the fimTU-pilVWXY1Y2E operon, (iii) AlgR regulates HCN production, and (iv) AlgR controls transcription of the putative cbb3-type cytochrome PA1557.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen capable of causing acute septicemia in patients with severe burns or severe immunodeficiency and chronic pneumonia in individuals with the genetic disease cystic fibrosis (CF) (5). The chronic pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of CF patients (24). The mucoid phenotype of P. aeruginosa, characterized by production of the exopolysaccharide alginate, is almost exclusively associated with chronic CF pneumonia (10, 15, 26, 43, 60). Alginate, composed of a linear copolymer of β-d-mannuronic and α-l-guluronic acids (17, 30, 31), confers a selective advantage on P. aeruginosa in the CF patient lung. Alginate insulates the bacterium from killing mechanisms of phagocytes such as hypochlorite (52-54) and prevents phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by neutrophils and macrophages (43). Because of the selective advantage that mucoidy confers on P. aeruginosa, the mechanism of alginate production has been studied extensively (26).

Alginate production is tightly controlled by a number of transcriptional regulators (26). One alginate regulatory system involves the MucA, MucB, MucC, and MucD proteins (6, 36, 38, 51) and their regulation of the sigma factor AlgU (AlgT) (27, 37, 61). Two studies examining clinical CF isolates from different locations found that a large percentage of the mucoid strains had mucA mutations. The first study, using CF isolates from North America and Europe, reported that 84% of mucoid isolates tested contained a mutation in mucA (7), while the second study, using CF strains isolated in Australia, found that 22 of the 50 (44%) mucoid strains tested contained mucA mutations (4). Mutations in mucA prevent MucA, an anti-sigma factor, from binding to AlgU, thus allowing AlgU to initiate transcription of algD and subsequently the alginate biosynthetic operon (36, 51). Additionally, the periplasmic protein MucB (51) is required for alginate regulation since mutations in mucB also cause the conversion of P. aeruginosa from a nonmucoid to a mucoid phenotype (35).

The transcriptional regulator AlgR is also required for alginate production (13). AlgR is a member of the LytTR family of two-component transcriptional regulators (12, 41). AlgR regulates alginate production by binding to three sites within the algD promoter, thereby activating transcription (39, 40). It has been proposed that AlgR causes a looping of the algD promoter that is required for transcriptional activation (50). Additionally, AlgR regulates alginate production through algC by binding to its promoter (62, 63). AlgC is a bifunctional enzyme with both phosphomannomutase and phosphoglucomutase activity (9) that is required not only for alginate production (62) but also for rhamnolipid production (42) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) expression (9). AlgR binds to three positions within the algC promoter region (21, 63), yet the orientation and positioning of the AlgR binding sites differ in the algC and algD promoters. The differences in orientation of the AlgR binding sites and of the AlgR binding affinities between the algC and algD promoters and their effects on the mechanism of AlgR regulation in vivo have not been clearly established.

More recent studies have indicated that AlgR regulates additional genes besides those required for alginate production. AlgR has been shown to be required for twitching motility (59), a type of surface motility utilizing type IV pili. Recently we have shown that AlgR is required for virulence in an acute septicemia mouse model. This study also demonstrated that the cellular concentrations of AlgR are critical for proper virulence since the overexpression of AlgR in PAO1 made the organism avirulent in a murine septicemia model (32). Taken together, these studies expanded AlgR's role in virulence beyond its known role as a regulator of alginate production and implied a possible role for AlgR in acute P. aeruginosa infections as well.

While algR mutations have been documented to impact the phenotypes of twitching motility and reduced virulence, the genes that AlgR regulates in these processes have not been identified. The determination of the genomic sequence of the laboratory wild-type strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 (55) facilitated the development of an Affymetrix GeneChip microarray for P. aeruginosa PAO1. In this study, we used the P. aeruginosa Affymetrix GeneChip array to examine the expression profiles of nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strains grown to mid-log and early stationary phases and used AlgR overexpression in PAO1 to identify genes regulated by AlgR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic manipulations.

P. aeruginosa strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The algR mutation in PSL317 was generated by crossover PCR deleting all but 30 bp of algR. Briefly, two initial PCRs were done, the first using the primers argHF (5′-ATATATGAGCTCGGACCTGTCCGACCTGTTCC-3′) and MR5 (5′-CGTCGTATGCATCAGCTCTGA-3′) and the second using the primers MR6 (5′-GAGCTGATGCATACGACGCAGGACATTCATAAGCTCAGC-3′) and hemCR (5′-ATATATGAGCTCGGCTGGCGTAGGTGTTCGAG-3′). The products of these reactions contain complementary sequence (the 5′ end of primer MR6 is complementary to primer MR5) that allow for their use as the template for a subsequent crossover PCR, using argHF and hemCR as the primers. This product was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and subsequently subcloned into the suicide plasmid pCVD442 (16), creating pRKO442. Plasmid pRKO442 was moved into PAO1 by triparental conjugation as previously described (28), and exconjugates were initially selected for plasmid insertion by carbenicillin resistance and then for plasmid recombination by sucrose resistance. Potential recombinants were tested by PCR using the primers argHF and hemCR, and algR deletion was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | B. Holloway |

| PSL317 | ΔalgR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCMR7 | pVDtac24 algR | 39 |

| pVDZ′2R | pVDZ′2R algR | 32 |

| pCVD442 | ori RSK mob sacB Apr | 16 |

| pRKO442 | pCVD442 ΔalgR | This study |

| pVDtac39 | IncQ/P4 mob+tac lacIq | 11 |

| pVDtacPIL | pVDtac39 fimT fimU pilV pilW pilX pilY1 pilY2 pilE | This study |

For the complementation of the twitching motility defect, a PCR fragment containing the operon fimTU-pilVWXY1Y2E was generated using the oligonucleotides fimTF (5′-ATATATGAGCTCAAGTCCCGCGACCAGTGCG-3′) and pilER (5′-ATATATGAGCTCCTGGTTCGACGGTGTGCG-3′) and the proofreading polymerase Expand HiFi (Roche). This fragment was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into pVDtac39 (11), creating the plasmid pVDtacPIL. The orientation of the insert relative to the tac promoter was determined by HindIII digest.

RNA isolation and preparation for Affymetrix GeneChip analysis.

For mid-logarithmic-phase growth experiments, five independent replicates of P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PSL317 (PAO1 ΔalgR) were grown in 100 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth in a 250-ml baffled flask vigorously shaken at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4. For the AlgR overexpression experiments, three independent replicates of PAO1 harboring the plasmid pCMR-7 were grown in the presence of 300 μg of carbenicillin/ml to an OD600 of 0.2, at which time IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The culture was then grown to an OD600 of 0.4. For the stationary-phase experiments, three independent replicates of PAO1 and PSL317 were grown in 100 ml of LB broth in a 250-ml baffled flask vigorously shaken at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6. After the cultures were chilled in a dry ice-ethanol bath to stop RNA synthesis, approximately 109 bacteria were removed (1 ml for the mid-log cultures, 0.5 ml for the stationary-phase cultures), collected by centrifugation (8,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C), resuspended in Tris-EDTA with 1 mg of lysozyme/ml, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's instructions.

The quality of the RNA was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 electrophoretic system pre- and post-DNase treatment (Fig. 1). The RNA was treated with 2 U of DNase I (Ambion) for 15 min at 37°C to remove contaminating DNA. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 25 μl of DNase stop solution (50 mM EDTA, 1.5 M sodium acetate, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate). The DNase I was removed by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. Ten micrograms of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis, fragmentation, and labeling according to the Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array expression analysis protocol. Briefly, random hexamers (Invitrogen) were added (final concentration, 25 ng/μl) to the 10 μg of total RNA along with in vitro-transcribed Bacillus subtilis control spikes (as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array expression analysis protocol). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions under the following conditions: 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 60 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 70°C for 10 min. RNA was removed by alkaline treatment and subsequent neutralization. The cDNA was purified with use of the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 40 μl of buffer EB (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5). The cDNA was fragmented by DNase I (0.6 U/μg of cDNA; Amersham) at 37°C for 10 min and then end labeled with biotin-ddUTP with use of the Enzo BioArray Terminal Labeling kit (Affymetrix) at 37°C for 60 min. Proper cDNA fragmentation and biotin labeling were determined by gel mobility shift assay with NeutrAvadin (Pierce) followed by electrophoresis through a 5% polyacrylamide gel and subsequent DNA staining with SYBR Green I (Roche).

FIG. 1.

Agilent electrophoretograms of RNA used to generate cDNA hybridized to the Affymetrix Pseudomonas GeneChips. Shown are the elctrophoretograms obtained from an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 on RNA samples for two of the three conditions examined in this study. MW, molecular size standards, in kilobases. Pre-DNase PAO1-1 SP, total RNA sample from P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown to stationary phase before treatment with DNase. PAO1-1 SP, total RNA sample from P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown to stationary phase after DNase treatment. PAO1-2 SP and PAO1-3 SP, independent replicates of total RNA from stationary-phase-grown P. aeruginosa PAO1 after DNase treatment. PSL317-1 SP, PSL317-2 SP, and PSL317-3 SP, three independent replicates of total RNA samples from P. aeruginosa PSL317 (ΔalgR) grown to stationary phase after DNase treatment. PAO1-1 ML, PAO1-2 ML, and PAO1-3 ML, total RNA samples from three independent replicates of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown to mid-logarithmic phase after DNase treatment. PAO1-1 pCMR-7, PAO1-2 pCMR-7, and PAO1-3 pCMR-7, total RNA samples from three independent replicates of P. aeruginosa PAO1 harboring the AlgR overexpression plasmid pCMR-7 grown to mid-logarithmic phase after DNase treatment.

Microarray data analysis.

Microarray data were generated using Affymetrix protocols. Absolute expression transcript levels were normalized for each chip by globally scaling all probe sets to a target signal intensity of 500. Three statistical algorithms (detection, change call, and signal log ratio) were then used to identify differential gene expression in experimental and control samples. The detection metric (presence, absence, or marginal) for a particular gene was determined using default parameters in MAS software (version 5.0; Affymetrix). Batch analysis was performed in MAS to make pairwise comparisons between individual experimental and control GeneChips in order to generate change calls and a signal log ratio for each transcript. These data were imported into Data Mining Tools (version 3.0; Affymetrix) via an Affymetrix Laboratory Information Management System. Transcripts that were absent under both control and experimental conditions were eliminated from further consideration. Statistical significance of signals between the control and experimental conditions (P < 0.05) for individual transcripts was determined using the t test. We defined a positive change call as one in which greater than 50% of the transcripts had a call of increased (I) or marginally increased (MI) for up-regulated genes and decreased (D) or marginally decreased (MD) for down-regulated genes. Finally, the mean value of the signal log ratios from each comparison file was calculated. Only those genes that met the above criteria and had a mean signal log ratio of ≥1 for up-regulated transcripts and ≤1 for down-regulated transcripts were kept in the final list of genes. Signal log ratio values were converted from log2 and expressed as fold changes. The original raw data files have been deposited in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc.-Genomax shared workspace. These files are not publicly available.

Genome searches.

The PAO1 genome sequence was obtained from the Pseudomonas Genome Project (www.pseudomonas.com) (55). Sequence data were imported into MacVector (version 7.0; Eastman Kodak) for analysis. The subsequence search of the PAO1 genome was done using the known AlgR binding sequences (CCGTTCGTC, CCGTTTGTC, CCGTTGTTC, or CCGTGCGTC), allowing up to two mismatches. Gene function information was obtained from the PseudoCap annotation project (www.pseudomonas.com).

Twitching motility assay.

Twitching motility was determined as previously described (1). Briefly, overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, PSL317 in LB medium, and PSL317(pVDtacPIL) grown in LB medium with 300 μg of carbenicillin/ml were stabbed through a twitching motility plate (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, 1% agar) supplemented with 1 mM IPTG. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h, at which time the agar was removed, the bacteria attached to the plate were stained with crystal violet, and the diameter of the zone of twitching was measured.

Western blot analysis.

P. aeruginosa strains PAO1, PSL317, and PSL317(pVDtacPIL) were grown in LB medium with aeration to mid-log phase (OD600 of 0.4). The stains were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 2 min), washed, resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl, and then lysed by sonication. Protein extracts (25 μg) were separated on a 4 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) and then electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was probed with an anti-AlgR monoclonal antibody (14), detected using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse monoclonal antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and developed using Opti-4CN (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

S1 nuclease protection assay and primer extension analysis.

The RNA for the S1 nuclease protection assay was isolated from mid-log-phase-grown PAO1 and PSL317 with the use of CsCl as previously described (37). The S1 nuclease protection assay was performed as previously described (37) with the following modifications. The hcnA 354-bp promoter region ranging from −330 to +24 (numbering relative to translational start site) was cloned into M13mp18. Single-stranded phage were isolated and used as the template for the uniformly labeled ([α-32P]dCTP) single-stranded DNA probe generated using the oligonucleotide hcnAprimext (5′-GTGTTGACGACGTTCAAGAAGGTGCAT-3′). The probe was digested using BglI and purified on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. The S1 nuclease reaction was performed as previously described (37) with the use of 50 μg of RNA from each strain. The sequencing ladder was generated using the same primer that was used to make the probe.

For the primer extension assay on the PA1557 promoter, RNA was isolated from PAO1, PSL317, and PAO1(pCMR7) grown as described above with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). The primer extension was done as previously described (18) with slight modifications. Briefly, the PA1557R′ primer (5′-GCGGACCACCTTGTAGTTATAGGCG-3′) was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP with the use of polynucleotide kinase and purified through a G-25 spin column (Amersham). The primer was hybridized to 10 μg of total RNA in hybridization buffer (0.5 M KCl, 0.24 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]), incubated at 95°C for 1 min and 55°C for 2 min, and then placed on ice for 15 min. Superscript II (Invitrogen) was added, and the primers were extended according to the manufacturer's protocol. The extension reaction mixtures were loaded next to a sequencing ladder generated using the same primer.

HCN quantification.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) produced by P. aeruginosa strains was quantified using the protocol of Gallagher and Manoil (23) with slight modifications. In brief, strains PAO1, PSL317, PAO1(pCMR7), and PSL317(pVDZ′2R) were grown on Pseudomonas isolation agar (Difco) for 24 h at 37°C and then enclosed without the lid in individual sealed plastic bags that contained 1 ml of 4 M NaOH. After 4 h of incubation, the NaOH was diluted to 0.09 M to bring it within linear range of a KCN standard curve. Then 105-μl aliquots of the samples were mixed with 350 μl of a 1:1 mixture of 0.1 M O-dinitrobenzene (ACROS) in ethylene-glycol monoethyl ether (ACROS) and 0.2 M p-nitrobenzaldehyde (ACROS) in ethylene-glycol monoethyl ether. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the OD578 was measured as previously described (23) and the HCN produced by each strain was quantified by comparison with a KCN standard curve.

RESULTS

Transcriptional profile of the AlgR regulon in P. aeruginosa PAO1 during mid-log growth phase.

We have recently shown that AlgR is essential for virulence of nonmucoid P. aeruginosa in an acute murine septicemia model (32). Since PAO1 does not produce significant amounts of alginate and since LPS was unaffected in the algR mutant strain PAO700 (algR::Gmr), the known AlgR-regulated genes, algD and algC, probably were not the reason for the differences in virulence observed between PAO1 and PAO700 (algR::Gmr). Furthermore, this study also suggested that AlgR regulates genes involved in P. aeruginosa response to oxidative stress (32). Therefore, in order to determine the extent of the AlgR regulon, we initiated a microarray study using the Affymetrix P. aeruginosa GeneChip Array. In the initial analysis, RNA was isolated from P. aeruginosa grown in LB medium to mid-logarithmic growth phase, mimicking the same conditions that were used in our previous virulence study (32). In order to identify the AlgR-regulated genes, transcripts from the wild-type strain PAO1 were compared to those of its isogenic algR in-frame deletion mutant PSL317 (ΔalgR) (see Materials and Methods). Here, AlgR activated the expression of 58 genes (Fig. 2) that fall into 16 of the functional classes used by the Pseudomonas Genome Project. Most of the AlgR-activated genes in mid-log phase (15) are categorized as hypothetical, uncharacterized, or unknown, but AlgR also activates a number of genes involved in (i) energy metabolism (11 genes), (ii) amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism (7 genes), (iii) cell wall-LPS-capsule production (6 genes), and (iv) the transport of small molecules (3 genes). These data indicate that AlgR may be required for the global expression of genes in P. aeruginosa and not just as a regulator for the specific pathways of alginate production and twitching motility.

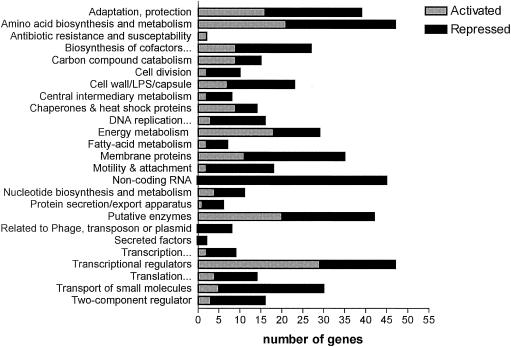

FIG. 2.

Functional classes of AlgR-regulated genes from mid-logarithmic growth phase. The genes were identified as either activated or repressed by AlgR with the use of the comparison of gene expression in PAO1 compared to PSL317 (ΔalgR) grown as described in Materials and Methods. All genes that had a significant difference in expression (P < 0.05 as determined by t test) are included. Functional classes were determined using the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com) on 14 January 2004.

A previous examination of protein expression in PAO1 and PAO700 (algR::Gmr) by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis found that 17 proteins were repressed by AlgR (32). Consistent with these results were those of the transcriptional analysis study comparing PAO1 and PSL317 (ΔalgR), whereby AlgR was found to repress expression of 37 genes during mid-logarithmic growth (Fig. 2). Two functional classes were identified as having the largest number of both AlgR-activated and AlgR-repressed genes: energy metabolism (11 activated, 5 repressed) and amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism (7 activated, 4 repressed). Table 2 includes a list of these genes that showed the highest degree of AlgR regulation, defined as greater-than-threefold activation or repression. Overall, the analysis of the microarray data suggests that AlgR is capable of affecting diverse functions in P. aeruginosa through either activation or repression.

TABLE 2.

Genes that had a greater-than-threefold AlgR activation or repression in PAO1 during mid-logarithmic growth

| PA no. | Gene name | Fold activationa | P valueb | Protein descriptionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA0141 | −4.2 | 0.049 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| PA0171 | 3.5 | 0.020 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1127 | −4.1 | 0.001 | Probable oxidoreductase | |

| PA1414 | −9.4 | 0.004 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1429 | −3.4 | 0.020 | Probable cation-transporting P-type ATPase | |

| PA1546 | hemN | −5.0 | 0.030 | Oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase |

| PA1555 | −7.4 | 0.025 | Probable cytochrome c | |

| PA1556 | −8.3 | 0.041 | Probable cytochrome c oxidase subunit | |

| PA1557 | −4.4 | 0.042 | Probable cytochrome oxidase subunit (cbb3 type) | |

| PA2119 | −7.5 | 0.019 | Alcohol dehydrogenase (Zn dependent) | |

| PA2194 | hcnB | −3.0 | 0.047 | HCN synthase HcnB |

| PA2491 | 14.3 | <0.001 | Probable oxidoreductase | |

| PA2493 | mexE | 7.5 | <0.001 | RNDd multidrug efflux membrane fusion protein MexE precursor |

| PA2494 | mexF | 17.3 | <0.001 | RND multidrug efflux transporter MexF |

| PA3278 | −8.0 | 0.030 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA3309 | −6.8 | 0.041 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| PA3458 | −3.0 | 0.022 | Probable transcriptional regulator | |

| PA3472 | 3.7 | <0.001 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA3582 | glpK | −4.0 | 0.032 | Glycerol kinase |

| PA4607 | oprG | −8.0 | 0.028 | Outer membrane protein OprG precursor |

| PA4348 | −4.4 | 0.040 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| PA4352 | −4.5 | 0.024 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| PA4354 | 6.1 | 0.026 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| PA4577 | −4.6 | 0.023 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA4613 | katB | 3.2 | 0.017 | Catalase |

| PA4916 | −3.2 | 0.048 | Probable c-type cytochrome | |

| PA5171 | arcA | −6.5 | 0.035 | Arginine deiminase |

| PA5261 | algR | 13.8 | <0.001 | Alginate biosynthesis regulatory protein AlgR |

| PA5497 | −3.2 | 0.004 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA5506 | −4.4 | 0.022 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA5507 | −5.4 | 0.006 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA5508 | −5.6 | 0.030 | Probable glutamine synthetase | |

| PA5509 | −7.3 | 0.021 | Hypothetical protein |

Fold activation was determined by comparing the transcription of PAO1 to that of its isogenic algR mutant PSL317. Five replicates of each strain were used for the comparison. Genes whose transcription was higher in PAO1 than in PSL317 were called AlgR activated and are represent by a positive fold activation value. Genes whose transcription was higher in PSL317 than in PAO1 were called AlgR repressed and are represented with a negative fold activation value. Only genes with a statistically significant difference in transcription (P < 0.05) between PAO1 and PSL317 and a greater-than-threefold AlgR activation or repression are shown.

P values were determined by Student's t test with Data Mining Tools (Affymetrix).

Protein descriptions are from the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com).

RND, resistance-nodulation-division.

Transcriptional profile of the AlgR regulon in P. aeruginosa PAO1 during stationary growth phase.

In P. aeruginosa the sigma factor RpoS has been shown to regulate a number of virulence factors in stationary phase, including two which are AlgR regulated: alginate production and type IV pili (56). With this in mind, we hypothesized that AlgR acts as a regulator not only in mid-logarithmic phase as shown in this study but also in stationary phase. We therefore compared the transcriptional profiles from PAO1 and PSL317 (ΔalgR) grown to early stationary phase in LB broth. Our analysis identified 45 genes that are activated by AlgR when P. aeruginosa enters stationary phase (Fig. 3). These genes fell into 14 functional classes with the majority (12 genes) of the genes categorized as hypothetical, followed by putative enzymes (6 genes), genes encoding putative membrane proteins (6 genes), genes involved in motility and attachment (6 genes), and genes encoding proteins for the transport of small molecules (5 genes).

FIG. 3.

Functional classes of AlgR-regulated genes from early stationary phase. The genes were identified as either activated or repressed by AlgR with use of the comparison of gene expression in PAO1 and in PSL317 (ΔalgR) grown as described in Materials and Methods. All genes that had a significant difference in expression (P < 0.05 as determined by t test) are included. Functional classes were determined using the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com) on 14 January 2004.

The analysis of PAO1 and PSL317 gene expression from stationary phase also identified 14 genes that are repressed by AlgR in early stationary phase (Fig. 3), once again indicating that AlgR activated and repressed gene expression. These genes were spread fairly evenly among eight functional classes. The genes from this study which had a greater-than-threefold activation or repression by AlgR are listed in Table 3. All but two of the most highly AlgR-regulated genes are activated by AlgR conditionally in early stationary phase. Other than algR itself, only one open reading frame (ORF), PA3472, encoding a hypothetical protein, was identified as highly AlgR regulated in both mid-logarithmic growth (Table 2) and early stationary phase (Table 3). The large number of AlgR-regulated genes that do not overlap between mid-log and stationary phases indicates that AlgR may regulate two independent sets of genes under these conditions.

TABLE 3.

Genes that had a greater-than-threefold AlgR activation or repression in PAO1 during early stationary phase

| PA no. | Gene name | Fold activationa | P valueb | Protein descriptionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA0694 | exbD2 | −4.3 | 0.030 | Transport protein ExbD |

| PA1048 | 5.0 | 0.033 | Probable outer membrane protein precursor | |

| PA1072 | braE | 3.6 | 0.05 | Branched-chain amino acid transport protein BraE |

| PA1106 | 4.5 | 0.002 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA1184 | −3.8 | 0.046 | Probable transcriptional regulator | |

| PA1355 | 4.3 | 0.040 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA2555 | 3.0 | 0.046 | Probable AMP-binding enzyme | |

| PA3472 | 3.0 | 0.025 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA3501 | 4.6 | 0.036 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA3709 | 4.2 | 0.029 | Probable major facilitator superfamily transporter | |

| PA4501 | 3.5 | 0.009 | Probable porin | |

| PA4552 | pilW | 4.9 | 0.020 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilW |

| PA4553 | pilX | 8.5 | 0.008 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilX |

| PA4554 | pilY1 | 3.4 | 0.044 | Type 4 fimbrial biogenesis protein PilY1 |

| PA5261 | algR | 16.0 | 0.016 | Alginate biosynthesis regulatory protein AlgR |

Fold activation was determined by comparing the transcription of PAO1 to its isogenic algR mutant PSL317. Three replicates of each strain were used for the comparison. Genes whose transcription was higher in PAO1 than in PSL317 were called AlgR activated and are represented by a positive fold activation value. Genes whose transcription was higher in PSL317 than in PAO1 were called AlgR repressed and are represented with a negative fold activation value. Only genes with a statistically significant difference in transcription (P < 0.05) between PAO1 and PSL317 and a greater-than-threefold AlgR activation or repression are shown.

P values were determined by Student's t test with Data Mining Tools (Affymetrix).

Protein descriptions are from the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com).

Transcriptional profile of the AlgR regulon in P. aeruginosa PAO1 overexpressing AlgR.

It is known that AlgR expression is increased during mucoid growth due to AlgU-initiated expression (37). Additionally, overexpression of algR in PAO1 (the nonmucoid background) renders PAO1 avirulent in a mouse septicemia model (32), thus indicating that the relative amounts of AlgR may be critical for gene regulation. In order to determine how these levels of AlgR affect gene expression, we compared the expression profiles of PAO1 and PAO1 overexpressing algR from the plasmid pCMR7. Our analysis indicated that overexpression of AlgR activated the expression of 312 genes and repressed the transcription of 573 genes (Fig. 4). The majority (41%) of these genes were uncharacterized or hypothetical genes. A large number of transcriptional regulators and two-component regulatory systems were identified as AlgR regulated, both activated and repressed, when AlgR was overexpressed. Thus, the large number of genes that were identified as AlgR regulated is likely in part due to indirect AlgR regulation through a second transcriptional regulator.

FIG. 4.

Functional classes of AlgR-regulated genes when AlgR was overexpressed from the plasmid pCMR7. The genes were identified as either activated or repressed by AlgR by use of the comparison of gene expression in PAO1 and in PAO1 overexpressing AlgR grown as described in Materials and Methods. All genes that had a significant difference in expression (P < 0.05 as determined by t test) are included. Functional classes were determined using the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com) on 14 January 2004.

The most highly AlgR-regulated genes were identified by combining genes whose transcription was either activated or repressed threefold by AlgR during overexpression and in mid-logarithmic or stationary phase (Table 4). Only 16 genes met these criteria (Table 4). Only one gene, PA1048, was shared between the lists of highly AlgR-regulated genes in stationary phase and during AlgR overexpression. The remaining genes were highly regulated by AlgR in mid-log growth and during AlgR overexpression. AlgR repressed the transcription of 11 genes during both mid-log growth and AlgR overexpression, indicating that the presence of AlgR may be enough to repress transcription.

TABLE 4.

Genes that had a greater-than-threefold AlgR activation or repression when AlgR was overexpressed and in either mid-log growth or early stationary phase

| PA no. | Gene name | Fold activationa

|

Protein descriptionb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-log phase | Stationary phase | Overexpression | |||

| PA1048 | 5.0 | −5.5 | Probable outer membrane protein precursor | ||

| PA1414 | −9.4 | −17.1 | Hypothetical protein | ||

| PA1546 | hemN | −5.0 | −6.7 | Oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | |

| PA1555 | −7.4 | −12.4 | Probable cytochrome c | ||

| PA1556 | −8.3 | −9.3 | Probable cytochrome c oxidase subunit | ||

| PA1557 | −4.4 | −3.0 | Probable cytochrome oxidase subunit (cbb3 type) | ||

| PA2119 | −7.5 | −4.0 | Alcohol dehydrogenase (Zn dependent) | ||

| PA2493 | mexE | 7.5 | −9.3 | RNDc multidrug efflux membrane fusion protein MexE precursor | |

| PA2494 | mexF | 17.3 | −7.6 | RND multidrug efflux transporter MexF | |

| PA3309 | −6.8 | −9.6 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| PA4067 | oprG | −8.0 | −8.9 | Outer membrane protein OprG precursor | |

| PA4348 | −4.4 | −13.3 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| PA4352 | −4.5 | −4.3 | Conserved hypothetical protein | ||

| PA4613 | katB | 3.2 | 5.0 | Catalase | |

| PA5171 | arcA | −6.5 | −10.5 | Arginine deiminase | |

| PA5261 | algR | 13.8 | 16.0 | −8.0 | Alginate biosynthesis regulatory protein AlgR |

Fold activation is defined in Table 2. The expression of all the genes listed was statistically different (P < 0.05 as determined by t test), and greater than threefold different in the mid-log phase is the comparison of transcription in mid-log-phase-grown PAO1 to that in PSL317 (ΔalgR). Stationary phase is the comparison of transcription in stationary-phase-grown PAO1 to that in PSL317 (ΔalgR). Overexpression is the comparison of transcription in mid-log-phase-grown PAO1 to that in PAO1 overexpressing AlgR from the plasmid pCMR7.

Protein descriptions were taken from the Pseudomonas Genome Project website (www.pseudomonas.com) on 14 January 2004.

RND, resistance-nodulation-division.

Identification of AlgR-regulated twitching motility genes in P. aeruginosa.

AlgR regulates twitching motility (59); however, the specific pilus gene(s) that AlgR controls has not been identified. We compared the P. aeruginosa Affymetrix GeneChip expression profiles of mid-log- and stationary-phase-grown PAO1 and PSL317 (ΔalgR) and of PAO1 and a PAO1 AlgR-overproducing strain in order to identify known pilus genes that may be AlgR regulated. Surprisingly, our initial analysis comparing PAO1 and PSL317 in the mid-log growth phase identified no known pilus genes. However, the expression profiles of PAO1 and PSL317 grown to early stationary phase did identify a single operon consisting of the genes fimU, pilV, pilW, pilX, pilY1, and pilY2 as potentially activated by AlgR (Table 5). The fold changes varied from 8.46 for pilX to 2.20 for fimU and pilV.

TABLE 5.

Known pilus genes identified as activated by AlgR

| PA no. | Gene name | Fold activation

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1/PAO1(pCMR7) (overexpressiona) | PAO1/PSL317 (stationary phaseb) | ||

| PA0395 | pilT | 1.34 | |

| PA0410 | pilI | 1.15 | |

| PA3805 | pilF | ||

| PA4527 | pilC | 2.40 | |

| PA4550 | fimU | 2.20 | |

| PA4551 | pilV | 2.20 | |

| PA4552 | pilW | 4.86 | |

| PA4553 | pilX | 8.46 | |

| PA4554 | pilY1 | 3.43 | |

| PA4555 | pilY2 | 2.22 | |

| PA5040 | pilQ | 2.38 | |

| PA5042 | pilO | 2.38 | |

| PA5043 | pilN | 1.24 | |

| PA5044 | pilM | 2.3 | |

Fold activation in PAO1 over that in PAO1(pCMR7) grown to mid-log phase as described in Materials and Methods.

Fold activation in PAO1 over that in PSL317 grown to stationary phase as described in Materials and Methods.

Since fimU, pilV, pilW, pilX, pilY1, and pilY2 were identified as among the most highly activated AlgR-regulated genes, the entire operon consisting of fimT, fimU, pilV, pilW, pilX, pilY1, pilY2, and pilE was cloned into the plasmid pVDtac39 (pVDtacPIL) and tested for its ability to complement the twitching motility defect in the algR deletion strain PSL317. PSL317 harboring the plasmid pVDtacPIL had approximately the same zone of twitching motility as did PAO1 (Fig. 5A and B). A Western blot assay to detect AlgR in PAO1, PSL317, and PSL317 harboring pVDtacPIL confirmed that the complementation of the twitching motility defect was due to the genes introduced on the plasmid and not due to an effect by AlgR (Fig. 5C). While PAO1 did produce a statistically larger twitching motility zone (Fig. 5B), the near-complete complementation of the twitching motility defect indicates that the genes included in this operon are the genes responsible for the twitching motility defect seen in an algR mutant.

FIG. 5.

Expression of fimT, fimU, pilV, pilW, pilX, pilY1, pilY2, and pilE in trans complemented the twitching motility defect in the algR mutant PSL317. (A) Representative photographs of the twitching motility of the wild-type strain PAO1, the algR mutant PSL317 (ΔalgR), and PSL317 containing the complementation plasmid pVDtacPIL showing the zone of twitching motility. (B) Quantified twitching motility zones for PAO1, PSL317, and PSL317(pVDtacPIL) (n = 5 for all strains). No twitching motility was observed for PSL317 on any replicate. Error bars represent standard errors. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. (C) Western blot analysis of AlgR production in PAO1 (lane 1), PSL317 (lane 2), and PSL317(pVDtacPIL) (lane 3). Equivalent amounts of total protein (25 μg) were separated on a 4 to 20% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were blotted and probed with an anti-AlgR monoclonal antibody (see Materials and Methods). MW, molecular weight standards (weights are given at left in thousands).

AlgR regulates HCN production in P. aeruginosa.

Since our transcriptional profiling analyses revealed that AlgR may be acting as a repressor of transcription, we chose to examine the transcription of two genes repressed by AlgR. One of the genes selected was hcnA, the first gene in the hcnABC operon that encodes the HCN synthase (29). This operon was selected for several reasons. First, Firoved and Deretic demonstrated that hcnA is activated in mucoid P. aeruginosa (19). Because AlgU increases algR expression in mucoid P. aeruginosa (37), their results may indicate that increased hcnA transcription in mucoid P. aeruginosa may be due to AlgR. Second, the transcriptional regulation of hcnA has been well studied. Two transcriptional start sites for hcnA (T1 and T2) have been identified (45) (Fig. 6B), and a number of transcription factors including ANR (29), LasR and RhlR (45) and the rsmA product (46) regulate the expression of hcnA. Third, the HCN synthase produces an assayable end product, HCN, allowing confirmation of transcriptional expression.

FIG. 6.

AlgR regulates hcnA transcription and HCN production. (A) An S1 nuclease protection analysis of hcnA promoter activity in strains PAO1 and PSL317 (ΔalgR) showing AlgR repression of the two previously identified transcriptional start sites, T1 and T2 (45). (B) The hcnA promoter sequence, highlighting the positions of the T1 and T2 transcriptional start sites, the previously identified ANR box (45), and the translational start site. Arrows indicate the positions of the previously published T1 and T2. The underlined bases indicate the mapped transcriptional start site seen in the S1 nuclease protection assay (panel A). (C) HCN production from strains PAO1, PSL317 (ΔalgR), PAO1(pCMR7) (AlgR overexpression), and PSL317(pVDZ′2R) (algR complementation) correlates with the difference in hcnA transcription. ***, P < 0.001 compared to PSL317 as determined by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test.

Analysis of our data from the Affymetrix GeneChip on PAO1 and PSL317 grown to mid-log phase indicated that AlgR repressed the transcription of the hcnABC operon by approximately threefold (hcnB = 3.0). To confirm AlgR dependence of the hcnA promoter, an S1 nuclease protection assay was performed comparing transcription in PAO1 and PSL317 (ΔalgR) grown under the same conditions that were used in the transcriptional profiling experiments. The results of the S1 nuclease protection assay show that AlgR repressed both the T1 promoter and the T2 promoter of hcnA under these growth conditions (Fig. 6A).

A quantitative HCN assay was performed on PAO1 and PSL317 to determine if the difference in transcription of the hcnABC operon corresponds to a difference in HCN production. The results of that assay demonstrated that PSL317 produced 1,479.4 μM HCN while PAO1 produced only 445.0 μM HCN, a 3.3-fold difference in HCN production. Complementation of algR in trans returned the production of HCN to near-wild-type levels (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that the differences in transcription caused by AlgR repression of both hcnA promoters result in an equivalent decrease in HCN produced by PAO1 compared to that for PSL317. Moreover, overexpression of AlgR eliminated HCN production in PAO1, indicating further that AlgR repressed hcnA expression (Fig. 6C). This series of experiments demonstrated that AlgR repressed transcription of hcnA and that mutations in algR resulted in increased HCN production in PAO1.

AlgR regulates expression of PA1557, a putative cbb3-type cytochrome.

Our transcriptional profiling analyses revealed that AlgR may be acting as a repressor. We therefore chose to examine the transcription of a second gene, PA1557, repressed by AlgR. ORF PA1557, followed by PA1556 and PA1555, comprises a putative cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase operon that shows the highest homology to the nitrogen fixation operon fixNOQP of Bradyrhizobium japonica (47). According to sequence analysis (www.pseudomonas.com) P. aeruginosa contains two operons (PA1557 to PA1555 and PA1554 to PA1552) with homology to fixNOP with both of the P. aeruginosa operons missing fixQ. It appears that only the PA1557 to PA1555 operon was AlgR regulated (Tables 2 and 4). We confirmed AlgR dependence of the uncharacterized ORF PA1557 in two different conditions, the PAO1 at mid-log growth phase and the AlgR overexpression condition. A primer extension experiment was performed to map the transcriptional start sites of PA1557, which revealed the presence of two transcriptional starts for PA1557, P1 and P2 (Fig. 7), with the P1 promoter of PA1557 appearing to be the promoter that is repressed by AlgR in both conditions. These results are in agreement with the differences in expression observed in the transcriptional profiling experiments.

FIG. 7.

The P1 promoter of PA1557 is AlgR dependent. (A) The primer extension analysis of the PA1557 promoter in PAO1, PSL317 (ΔalgR), and PAO1 overexpressing AlgR from the plasmid pCMR7 (PAO1 pCMR7) identified two promoters, P1 and P2. The GATC lanes comprise a sequencing ladder generated from the same primer that was used in the primer extension. (B) Sequence map of the PA1557 promoter indicating the positions of the P1 and P2 promoters relative to the putative translational start site (underlined) in addition to the position of two putative AlgR binding sites (ARBS-1 and ARBS-2) and a putative ANR box.

DISCUSSION

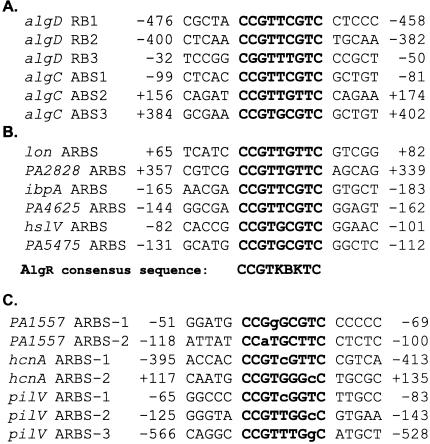

In this study we have identified four new roles for the P. aeruginosa transcriptional regulator AlgR: (i) AlgR can repress gene transcription; (ii) AlgR activates the fimTU-pilVWXY1Y2E operon, the expression of which is sufficient to correct the twitching motility defect in an algR mutant; (iii) AlgR regulates HCN production; and (iv) AlgR controls transcription of the putative cbb3-type cytochrome PA1557. Additionally, this study has given some insight into the mechanisms of AlgR regulation. AlgR regulates the transcription of the alginate genes algD and algC by directly binding to three sites within the algD promoter (39, 40) and the algC promoter (21, 63) (Fig. 8A). The position of the AlgR binding site varies greatly between the algD and algC promoters, ranging from −476 to −37 in the algD promoter and −99 to +402 in the algC promoter. An alignment of the published AlgR binding sites reveals the first base to be poorly conserved between the published sites. Removing the first base and using only the 9-bp sequences (shown in boldface in Fig. 8A) to search for putative AlgR binding sites in the promoter regions (defined as −873 to +402 relative to the translational start site) of genes found to be highly AlgR dependent (Table 4) revealed only six genes with algC or algD AlgR binding sites within their promoter (Fig. 8B). This result may indicate that (i) the AlgR binding sequence may only be partially known or (ii) the activated form of AlgR may bind to a different sequence. In support of the first possibility, AlgR has been proposed to be a member of a family of transcriptional regulators that may bind to imperfect direct repeats of the sequence pattern [TA][AC][CA]GTTN[AG][TG], suggesting that AlgR may be binding as a dimer to the promoters that it regulates (41). On the other hand, the affinity of AlgR for the algC ABS3 binding site is enhanced when AlgR is phosphorylated (61).

FIG. 8.

Alignment of AlgR binding sites of AlgR-regulated genes. (A) Alignment of the known AlgR binding sites from the algD (39, 40) and algC (21, 63) promoters. (B) Alignment of putative AlgR binding sites within the promoter regions of lon (PA1803), ibpA (PA3126), hslV (PA5053), PA2828, PA4625, and PA5475. The position of the AlgR binding site (in boldface) is relative to the putative translational start site. (C) Alignment of putative AlgR binding sites of PA1557, hcnA, and pilV promoter regions. Mismatched bases in the AlgR binding site are indicated by lowercase letters. The AlgR consensus sequence is a composite of the known AlgR binding sequences within the algD and algC genes. B, G, C, or T; K, G or T.

Three characterized genes with algD or algC consensus AlgR binding sites in their promoters that showed AlgR dependence in our transcriptional profiles were ibpA, lon, and hslV, all potentially involved in the stress response of P. aeruginosa. The AlgR regulation of these three stress response genes not only increases the global relevance of the AlgR regulon but is also in accordance with other evidence that AlgR may play a role in stress. The expression of AlgR has been shown to be activated by the extreme heat shock sigma factor AlgU (37). In Escherichia coli IbpA (along with other small heat shock proteins) works in conjunction with the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE and the GroEL-GroES systems to manage environmental stress, but IbpA appears to be dispensable (57). It is interesting that dnaK also showed a twofold repression by AlgR in the AlgR overexpression experiment, but the dnaK promoter does not contain a putative AlgR binding sequence. Since P. aeruginosa ibpA has not been characterized and has only 67% homology with E. coli ibpA, the effects of the differing primary structures on IbpA function in the stress response of P. aeruginosa are unknown. It is possible that some of the genes that showed AlgR dependence but do not have an identifiable AlgR binding site could be regulated indirectly through proteolytic degradation of a transcription factor. Consistent with the hypothesis that AlgR may regulate P. aeruginosa stress genes, we have shown previously that the algR mutant strain PAO700 (algR::Gmr) was found to be more resistant to hydrogen peroxide, myeloperoxidase, and human neutrophils (31). We discovered two potential AlgR-regulated genes, katA and katB, from our global expression analysis that may account for the resistance phenotypes observed. The transcriptional profile of AlgR-dependent genes indicated that katA was repressed 1.80-fold by AlgR while katB was activated 3.16-fold by AlgR. P. aeruginosa contains at least three catalase genes: katA, katB, and katC (33). KatA is constitutively active and provides the major catalase activity in all phases of growth (8). In addition, the expression of KatA can be induced by oxidative stress (8). The expression of KatB is low under normal growth conditions but is activated in response to oxidative stress (8). Therefore, analysis of the AlgR transcriptional profile indicates that AlgR represses the expression of KatA, the “housekeeping” and most highly expressed catalase, which may result in the algR mutant producing more catalase than the wild type does. This may be one potential explanation for the observation that PAO700 was more resistant to H2O2 than was PAO1 (32).

Interestingly, another microarray study comparing the gene expression of P. aeruginosa strains PAK and PAK algZ (fimS) also identified fimU, pilV, pilW, pilX, pilY1, pilY2, and pilE as among the most AlgZ-dependent genes (M. Wolfgang, personal communication). Mutations in either algZ-fimS or algR result in elimination of the twitching motility phenotype (59). The fimU-pilVWXY1Y2 operon does contain two putative AlgR binding sites, although neither is identical to the algC or algD consensus AlgR binding sites. One putative AlgR binding site is located 79 bp from the 3′ end of fimU, directly upstream of pilV (Fig. 8C). The studies that characterized pilV identified a strong pilV promoter along with a second, weaker pilV promoter within the coding region of fimU (2, 3). Therefore, this putative AlgR site could be in the promoter region of pilV, indicating that AlgR could directly regulate pilV expression. Since the translational starts and stops for pilV, pilW, and pilX overlap (2, 3), it is possible that all three genes are regulated by the two potentially AlgR-dependent pilV promoters. The other putative AlgR binding site is located 947 bp into the coding region of pilY1. Due to the long distance of this site from an intergenic region, the potential function of this site is unknown. The AlgR overexpression transcriptional profile also identified an additional eight known pilus genes as potentially activated by AlgR (Table 5), including nearly the entire pilMNOPQ operon (only pilP did not show differential expression). Interestingly, pilMNOPQ mutants have been described as able to produce equivalent amounts of pilin but unable to express it on the cell surface as determined by electron microscopy and phage PO4 sensitivity assays (34). This is the same phenotype reported for an algR mutant (59). However, there are no putative AlgR binding sites in or near the promoter regions of most of the genes in the pilMNOPQ operon. There is one AlgR binding site identical to the algD RB1 site within the pilQ coding region, but it is 582 bp from the 3′ end of pilQ. The lack of AlgR binding sites near the 5′ end of this operon indicates that the pilMNOPQ operon is likely indirectly AlgR regulated. None of the promoter regions of the other genes, pilT, pilI, or pilC, contains a putative AlgR binding site, again indicating indirect AlgR regulation.

Other studies have shown that P. aeruginosa produces HCN in infected burn eschar of human patients and that HCN was detectable in the viscera upon postmortem analysis (25). A more recent study has identified HCN produced by P. aeruginosa as a primary virulence factor for the paralytic killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by P. aeruginosa (23), and other studies have shown HCN to be an inhibitor of fungal growth in plant leaf and root infection (20, 58). These studies indicate that the HCN produced by P. aeruginosa may affect host cells and may be important in virulence. There are two reported promoters for the hcnA gene, T1, controlled by quorum-sensing regulators alone, and T2, which appears to rely on a synergistic action of LasR, RhlR, and ANR (45). Currently, five hcnA regulatory proteins have been identified: GacA (48), ANR (48, 64), LasR and RhlR (45), and RsmA (46). The global regulator GacA positively controls HCN synthesis as well as other secondary metabolites and exoenzymes (48). P. aeruginosa mutants with mutations in gacA or anr produce very little HCN (48, 64). LasR and RhlR are quorum-sensing regulators required for transcription of the hcnA promoter (45). RsmA (regulator of secondary metabolites) functions as a pleiotropic posttranscriptional regulator of HCN synthesis directly and also indirectly by negatively regulating the amounts of quorum sensing N-acylhomoserine lactones (44). Since our data suggest that AlgR is affecting T1 and T2 transcription, AlgR is yet another transcriptional regulator involved with hcnA expression, indicating that AlgR and LasR and/or RhlR and ANR coordinately regulate this promoter. In support of this possibility, analysis of the hcnA promoter reveals a putative AlgR binding site from −400 to −408 bp upstream of the translational start site (Fig. 8C). This site (CCGTCGTTC) differs by only one base from the ABS2 site of algC (63) (Fig. 8A and C), indicating that AlgR may bind directly to the hcnA promoter to regulate its transcription.

The promoter of PA1557 shares some very interesting features with the promoter of hcnA. The first is that both promoters contain putative AlgR binding sites (Fig. 7B and 8C). Another similarity between the two promoters is that they contain a putative ANR binding site (Fig. 6B and 7B). In addition to hcnA and PA1557, two other genes that were AlgR dependent in the transcriptional profiling analysis (Tables 2 and 4) are known to be ANR dependent. The arcDABC operon, which encodes the anaerobic arginine deiminase enzymes (22), and hemN, which encodes the oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase (49), are both ANR dependent. None of the conditions that we examined by transcriptional profiling revealed that anr was AlgR regulated. The possible mechanism of AlgR and ANR coregulation is unknown, but the number of promoters (hcnA, PA1557, arcD, and hemN) regulated by both suggests more than coincidental regulation.

The fact that only 6 out of the 53 genes that show AlgR regulation in two out of the three conditions tested possess a known AlgR binding site indicates that the mechanism of AlgR regulation is more complex than originally thought. A relatively small number of AlgR-regulated genes without AlgR binding sites would have been expected due to indirect effects through other transcriptional regulators, but those regulators would have been expected to possess AlgR binding sites. However, none of the transcriptional regulators on the list of the genes most regulated by AlgR (Table 4) contain AlgR binding sites. The Lon and HslVU proteases certainly could account for a portion of the genes indirectly regulated by AlgR, but it is unlikely that the astounding numbers of genes that show indirect AlgR dependence are through these two proteases alone. The distinct possibility exists that AlgR is capable of binding to additional sequences that have yet to be elucidated. Most of the work describing the AlgR binding site was done in vitro using AlgR purified from E. coli (39, 40) or using crude cell extracts of P. aeruginosa that overexpresses AlgR (21, 63). Therefore, the effects of posttranslational modification were not taken into account. Further studies are warranted to discern the role of AlgR posttranslational modifications and the ability of AlgR to switch from a repressor to an activator in control of P. aeruginosa gene transcription.

Acknowledgments

Microarray equipment and technical support were supplied by the GeneChip Bioinformatics core at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

The cost of the P. aeruginosa GeneChips was defrayed in part by subsidy grant no. 024 from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. This work was supported by grants LEQSF (1999-02) RD-A-42 and HEF (2000-05)-06 from the State of Louisiana-Board of Regents and in part by grant AI050812-01A2 (NIH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, R. A., and J. S. Mattick. 1997. Genes involved in the biogenesis and function of type-4 fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 192:89-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm, R. A., and J. S. Mattick. 1995. Identification of a gene, pilV, required for type 4 fimbrial biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whose product possesses a pre-pilin-like leader sequence. Mol. Microbiol. 16:485-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alm, R. A., and J. S. Mattick. 1996. Identification of two genes with prepilin-like leader sequences involved in type 4 fimbrial biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 178:3809-3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony, M., B. Rose, M. B. Pegler, M. Elkins, H. Service, K. Thamotharampillai, J. Watson, M. Robinson, P. Bye, J. Merlino, and C. Harbour. 2002. Genetic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the sputa of Australian adult cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2772-2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodey, G. P., R. Bolivar, V. Fainstein, and L. Jadeja. 1983. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5:279-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher, J. C., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, D. W. Rowen, and V. Deretic. 1997. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: role of mucC in the regulation of alginate production and stress sensitivity. Microbiology 143:3473-3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 65:3838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, S. M., M. L. Howell, M. L. Vasil, A. J. Anderson, and D. J. Hassett. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the katB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encoding a hydrogen peroxide-inducible catalase: purification of KatB, cellular localization, and demonstration that it is essential for optimal resistance to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 177:6536-6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyne, M. J., K. S. Russell, C. L. Coyle, and J. B. Goldberg. 1994. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC gene encodes phosphoglucomutase, required for the synthesis of a complete lipopolysaccharide core. J. Bacteriol. 176:3500-3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deretic, V. 1996. Molecular biology of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cyst. Fibros. Curr. Top. 3:223-244. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deretic, V., S. Chandrasekharappa, J. F. Gill, D. K. Chatterjee, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. A set of cassettes and improved vectors for genetic and biochemical characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 57:61-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deretic, V., R. Dikshit, W. M. Konyecsni, A. M. Chakrabarty, and T. K. Misra. 1989. The algR gene, which regulates mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, belongs to a class of environmentally responsive genes. J. Bacteriol. 171:1278-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deretic, V., J. F. Gill, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1987. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis: nucleotide sequence and transcriptional regulation of the algD gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:4567-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deretic, V., J. H. J. Leveau, C. D. Mohr, and N. S. Hibler. 1992. In vitro phosphorylation of AlgR, a regulator of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, by a histidine protein kinase and effects of small phospho-donor molecules. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2761-2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doggett, R. G., G. M. Harrison, R. N. Stillwell, and E. S. Wallis. 1966. An atypical Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with cystic fibrosis of the pancreas. J. Pediatr. 68:215-221. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans, L. R., and A. Linker. 1973. Production and characterization of the slime polysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 116:915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firoved, A. M., J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 2002. Global genomic analysis of AlgU (σE)-dependent promoters (sigmulon) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and implications for inflammatory processes in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 184:1057-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Firoved, A. M., and V. Deretic. 2003. Microarray analysis of global gene expression in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:1071-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaishman, M. A., Z. Eyal, A. Zilberstein, C. Voissard, and D. Haas. 1996. Suppression of Septoria tritici blotch and leaf rust of wheat by recombinant cyanide-producing strains of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 9:642-645. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiwara, S., N. A. Zielinski, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1993. Enhancer-like activity of AlgR1-binding site in alginate gene activation: positional, orientational, and sequence specificity. J. Bacteriol. 175:5452-5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galimand, M., M. Gamper, A. Zimmermann, and D. Haas. 1991. Positive FNR-like control of anaerobic arginine degradation and nitrate respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 173:1598-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallagher, L. A., and C. Manoil. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 kills Caenorhabditis elegans by cyanide poisoning. J. Bacteriol. 183:6207-6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:35-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldfarb, W. B., and H. Margraf. 1967. Cyanide production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann. Surg. 165:104-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hershberger, C. D., R. W. Ye, M. R. Parsek, Z.-D. Xie, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1995. The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative σ factor (σE). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7941-7945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konyecsni, W. M., and V. Deretic. 1988. Broad-host-range plasmid and M13 bacteriophage-derived vectors for promoter analysis in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 74:375-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laville, J., C. Blumer, C. Von Schroetter, V. Gaia, G. Defago, C. Keel, and D. Haas. 1998. Characterization of the hcnABC gene cluster encoding hydrogen cyanide synthase and anaerobic regulation by ANR in the strictly aerobic biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J. Bacteriol. 180:3187-3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linker, A., and R. S. Jones. 1966. A new polysaccharide resembling alginic acid isolated from pseudomonads. J. Biol. Chem. 241:3845-3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linker, A., and R. S. Jones. 1964. A polysaccharide resembling alginic acid from a Pseudomonas micro-organism. Nature 204:187-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lizewski, S. E., D. S. Lundberg, and M. J. Schurr. 2002. The transcriptional regulator AlgR is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 70:6083-6093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma, J. F., U. A. Ochsner, M. G. Klotz, V. K. Nanayakkara, M. L. Howell, Z. Johnson, J. E. Posey, M. L. Vasil, J. J. Monaco, and D. J. Hassett. 1999. Bacterioferritin A modulates catalase A (KatA) activity and resistance to hydrogen peroxide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181:3730-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, C., M. A. Ichou, P. Massicot, A. Goudeau, and R. Quentin. 1995. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis revealed by restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rRNA gene region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1461-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin, D. W., B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: AlgU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J. Bacteriol. 175:1153-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, M. H. Mudd, J. R. W. Govan, B. W. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1994. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to stress response. J. Bacteriol. 176:6688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Salazar, J. M., S. Moreno, R. Najera, J. C. Boucher, G. Espin, G. Soberon-Chavez, and V. Deretic. 1996. Characterization of the genes coding for the putative sigma factor AlgU and its regulators MucA, MucB, MucC, and MucD in Azotobacter vinelandii and evaluation of their roles in alginate biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1800-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohr, C. D., N. S. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1991. AlgR, a response regulator controlling mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, binds to the FUS sites of the algD promoter located unusually far upstream from the mRNA start site. J. Bacteriol. 173:5136-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr, C. D., J. H. J. Leveau, D. P. Krieg, N. S. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1992. AlgR-binding sites within the algD promoter make up a set of inverted repeats separated by a large intervening segment of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 174:6624-6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikolskaya, A. N., and M. Y. Galperin. 2002. A novel type of conserved DNA-binding domain in the transcriptional regulators of the AlgR/AgrA/LytR family. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2453-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olvera, C., J. B. Goldberg, R. Sanchez, and G. Soberon-Chavez. 1999. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC gene product participates in rhamnolipid biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pederson, S. S., N. Høiby, and F. Espersen. 1992. Role of alginate in infection with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 47:6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pessi, G., and D. Haas. 2001. Dual control of hydrogen cyanide biosynthesis by the global activator GacA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pessi, G., and D. Haas. 2000. Transcriptional control of the hydrogen cyanide biosynthetic genes hcnABC by the anaerobic regulator ANR and the quorum-sensing regulators LasR and RhlR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182:6940-6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pessi, G., F. Williams, Z. Hindle, K. Heurlier, M. T. Holden, M. Camara, D. Haas, and P. Williams. 2001. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:6676-6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preisig, O., D. Anthamatten, and H. Hennecke. 1993. Genes for a microaerobically induced oxidase complex in Bradyrhizobium japonicum are essential for a nitrogen-fixing endosymbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3309-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reimmann, C., M. Beyeler, A. Latifi, H. Winteler, M. Foglino, A. Lazdunski, and D. Haas. 1997. The global activator GacA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO positively controls the production of the autoinducer N-butyryl-homoserine lactone and the formation of the virulence factors pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase. Mol. Microbiol. 24:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rompf, A., C. Hungerer, T. Hoffmann, M. Lindenmeyer, U. Romling, U. Gross, M. O. Doss, H. Arai, Y. Igarashi, and D. Jahn. 1998. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol. Microbiol. 29:985-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schurr, M. J., D. W. Martin, M. H. Mudd, N. S. Hibler, J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 1993. The algD promoter: regulation of alginate production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 39:371-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schurr, M. J., H. Yu, J. M. Martinez-Salazar, J. C. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 1996. Control of AlgU, a member of the σE-like family of stress sigma factors, by the negative regulators MucA and MucB and Pseudomonas aeruginosa conversion to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4997-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1988. Alginate inhibition of the uptake of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by macrophages. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1993. Alginate may accumulate in cystic fibrosis lung because the enzymatic and free radical capacities of phagocytic cells are inadequate for its degradation. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 30:1021-1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simpson, J. A., S. E. Smith, and R. T. Dean. 1989. Scavenging by alginate of free radicals released by macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 6:347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suh, S. J., L. Silo-Suh, D. E. Woods, D. J. Hassett, S. E. West, and D. E. Ohman. 1999. Effect of rpoS mutation on the stress response and expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181:3890-3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas, J. G., and F. Baneyx. 1998. Roles of the Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB in thermal stress management: comparison with ClpA, ClpB, and HtpG in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 180:5165-5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voisard, C., C. Keel, D. Haas, and G. Defago. 1989. Cyanide production by Pseudomonas fluorescens helps suppress black root rot of tobacco under gnotobiotic conditions. EMBO J. 8:351-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitchurch, C. B., R. A. Alm, and J. S. Mattick. 1996. The alginate regulator AlgR and an associated sensor FimS are required for twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9839-9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu, H., J. C. Boucher, N. S. Hibler, and V. Deretic. 1996. Virulence properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lacking the extreme-stress sigma factor AlgU (σE). Infect. Immun. 64:2774-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu, H., M. J. Schurr, and V. Deretic. 1995. Functional equivalence of Escherichia coli σE and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU: E. coli rpoE restores mucoidy and reduces sensitivity to reactive oxygen intermediates in algU mutants of P. aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 177:3259-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zielinski, N. A., A. M. Chakrabarty, and A. Berry. 1991. Characterization and regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC gene encoding phosphomannomutase. J. Biol. Chem. 266:9754-9763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zielinski, N. A., R. Maharaj, S. Roychoudhury, C. E. Danganan, W. Hendrickson, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1992. Alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: environmental regulation of the algC promoter. J. Bacteriol. 174:7680-7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmermann, A., C. Reimmann, M. Galimand, and D. Haas. 1991. Anaerobic growth and cyanide synthesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa depend on anr, a regulatory gene homologous with fnr of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1483-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]