Abstract

Objectives

Cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) complex condition, which may present to any healthcare professional and at any point during the cancer journey. As such, patients may be managed by a number of specialties, resulting in inconsistent practice and suboptimal care. We describe the development of a dedicated CAT service and its evaluation.

Setting

Specialist cancer centre, district general hospital and primary care.

Participants

Patients with CAT and their referring clinicians.

Intervention

A cross specialty team developed a dedicated CAT service , including clear referral pathways, consistent access to medicines, patient's information and a specialist clinic.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The service was evaluated using a mixed-methods evaluation , including audits of clinical practice, clinical outcomes, staff surveys and qualitative interviewing of patients and healthcare professionals.

Results

Data from 457 consecutive referrals over an 18-month period were evaluated. The CAT service has led to an 88% increase in safe and consistent community prescribing of low-molecular-weight heparin, with improved access to specialist advice and information. Patients reported improved understanding of their condition, enabling better self-management as well as better access to support and information. Referring clinicians reported better care standards for their patients with improved access to expertise and appropriate management.

Conclusions

A dedicated CAT service improves overall standards of care and is viewed positively by patients and clinicians alike. Further health economic evaluation would enhance the case for establishing this as the standard model of care.

Keywords: cancer associated thrombosis, service improvement, mixed methods, quality of life, patient journey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first description of a dedicated cancer-associated thrombosis service.

It provides quantitative and qualitative evidence of improved quality of care and reduction in avoidable harm.

It provides real-world data on the scope of patients with cancer-associated thrombosis presenting to a regional cancer centre.

It offers a readily reproducible service model that can be adopted across the health system.

While the benefits of the service model are clear, it has not been subjected to formal health economic evaluation.

Introduction

The association between malignancy and thrombosis is well established; cancer accounts for 18% of all cases of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and will occur in 20% of patients with cancer.1 The management of cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) is associated with particular clinical challenges.2 Anticoagulation with warfarin is associated with an increased risk of haemorrhage and recurrent thrombosis compared to patients without cancer.3 4 Consequently, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has demonstrated greater efficacy than warfarin in the treatment of CAT and remains the anticoagulant of choice in clinical guidelines.5–8 More recently, the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have demonstrated non-inferiority to warfarin in the treatment of VTE in the general population.9–12 While they are yet to be evaluated against LMWH for the treatment of CAT, their use in the cancer setting is increasing.13

Despite a strong evidence base for best practice, adherence to clinical guidelines is variable and decision-making is inconsistent across the specialties involved in the management of CAT.14 15 This problem is compounded by a lack of clinical ownership for CAT between oncology, haematology and primary care, thereby leading problems with accessing medication, follow-up and ongoing decision-making.16 17 Furthermore, the sequelae of CAT are not limited to the physical; recent research has suggested that it confers a significant symptomatic and psychological burden on patients and is considered by some to be more distressing than cancer itself.17 18 As such, a holistic approach to CAT is essential, particularly as these patients will also have needs within the context of their cancer journey.19 A recent case series of 221 US patients suggests that a centralised approach to the care of CAT reduces treatment variation and appears to reduce VTE-related hospitalisations.20 This leads to cost savings through reduction in recurrent VTE, bleeding and hospital admissions.

We describe the development and evaluation of a dedicated CAT service within a UK regional cancer centre.

Clinical context and need for new service

The dedicated CAT service was developed in response to an audit of the management of VTE in oncology patients attending a regional cancer centre, serving a population of 1.42 million with 7000 new cancer diagnoses per annum. Several areas of unmet need and opportunities for improvement were identified, including variation in clinical management, problems in accessing LMWH in the community, increased need for support and information and the absence of consistent access to specialist advice. These are summarised in box 1.

Box 1. Challenges to the provision of high-quality cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) management.

-

Inconsistent management of CAT and adherence to guidelines

Variation in practice was observed across clinical teams with respect to the following key areas of anticoagulation:- Measurement of baseline blood tests prior to starting low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH);

- Review of full blood count at day 5 post-LMWH initiation;

- Dose reduction of dalteparin after 1 month of anticoagulation;

- Decision on whether to continue or stop anticoagulation at 6 months for patients with ongoing active cancer.

-

Variable access to LMWH

LMWH would usually be initiated within the hospital setting with the expectation that ongoing anticoagulation would be managed by the primary care/family physician. Inconsistent willingness to take on this prescribing leads to increased distress for patients and unclear pathways of access to repeat prescriptions.

-

Need for information and support

Distress associated with suboptimal communication and lack of information was identified pertaining to:- Understanding the meaning and prognosis of CAT;

- LMWH injection techniques;

- Plans for follow-up.

-

Lack of consistent specialist expertise

Twenty per cent of patients required management beyond standard weight-adjusted LMWH therapy. There was no consistent pathway or access to expert advice on managing:- Recurrent venous thromboembolism;

- Bleeding;

- Thrombocytopenia;

- Interventions (eg, biopsies) and interruption of anticoagulation;

- Inferior vena cava filters.

A multiprofessional team with representation from oncology, haematology, primary care and palliative care devised a new model of working with the intention of improving the quality of patient care and experience while reducing variation, wastage and harm.

Development of new service

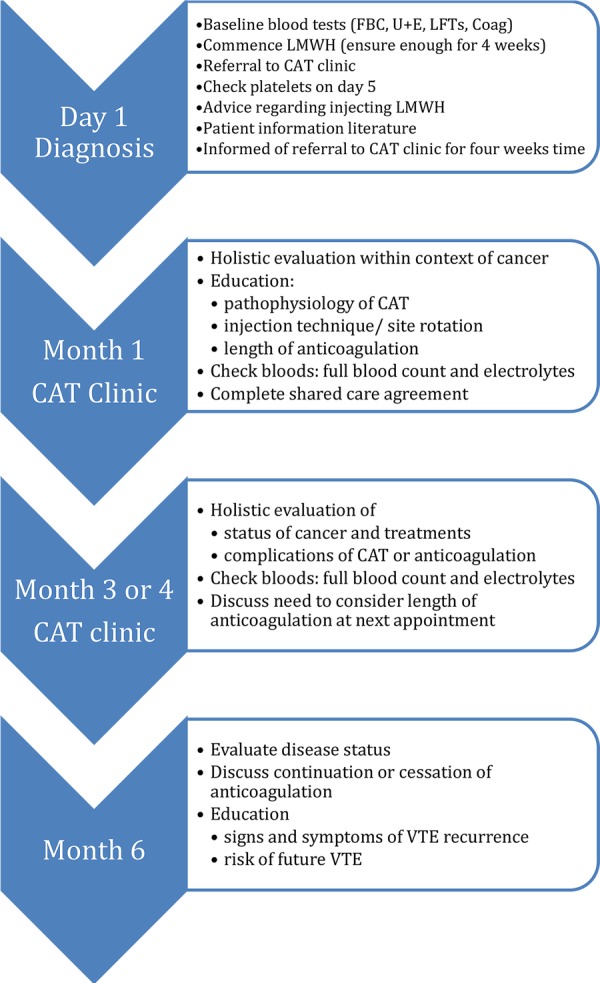

The patient journey and key components of the CAT service are summarised in figure 1. The new service was established through the implementation of four core components, described below. The service was funded through existing National Health Service resources, with no input financially or intellectually from any members of the pharmaceutical industry.

Figure 1.

Referral and management pathway for cancer-associated thrombosis. CAT, cancer-associated thrombosis; FBC, full blood count; U+E, urea and elctrolytes; LFT, liver function tests. LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin, VTE, venous thromboembolism

Shared care agreement for community prescribing of LMWH

A working group was established between clinical stakeholders within primary and secondary care to establish a shared care protocol, which would support the prescribing within primary care of LMWH for the treatment of VTE in solid tumours as per license. Once agreed, the relevant local prescribing and commissioning groups ratified this, after which details of the agreement were disseminated to all healthcare practitioners likely to be involved. Part of the prescribing agreement required primary care to sign and return the document indicating agreement to participate, thereby ensuring that the uptake of the shared care agreement was auditable.

Patient information leaflets

Two patient leaflets were designed to provide

Information about referral to the CAT clinic;

Advice on self-injecting LMWH.

The documents were developed in consultation with two patients currently being treated for CAT who offered advice regarding their preferred information needs at the time of diagnosis. Documents were then taken through local approval processes , including the patient partner group and plain English campaign (http://www.plainenglish.co.uk/).

Patient referral pathway

The patient pathway was piloted within one cancer centre and subsequently expanded to district general hospitals that fed into the tertiary centre. This was performed following a broad education programme to make clinicians aware of the new service. Referrals were made at the point of diagnosis of CAT to a dedicated CAT secretary and reviewed by the CAT clinician within 24 hours. The clinical team, responsible for the patient, did this at the time the CAT was diagnosed. A written referral would be faxed or emailed to the CAT secretary who would ensure that it was reviewed by one of the CAT clinicians (SN or NP) within 24 hours. They would decide how quickly the patient should. For the majority of patients with uncomplicated symptomatic or incidental VTE, an appointment would be sent to review within 4 weeks of diagnosis. At this time, the referring clinician would be responsible for:

Baseline blood tests: full blood count, renal and liver function and coagulation screen.

Providing 4 weeks of LMWH (patient information leaflets will be dispensed by pharmacy).

Ensuring that LMWH is administered by a trained patient/carer or domiciliary visit by the district nurse.

Check platelet count 5 days after LMWH initiated to check for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

On occasion, the clinician reviewing the referral may feel that the patient requires immediate review, for example, large volume clot burden, renal impairment and bleeding risk. For these patients, advice would be given to the referring clinician on receipt and a review arranged in the next available clinic.

Dedicated outpatient clinic

Details of issues covered in the clinic are summarised in figure 1. The first clinic appointment would occur 4 weeks post-CAT diagnosis, thereby ensuring that a review occurs at the time point for LMWH dose reduction (for centres where dalteparin was used). Practical issues that are addressed during this first appointment include reviewing injection technique, evaluation for any episodes suggestive of bleeding or recurrent CAT, and ensuring that the shared care agreement is completed. The clinician will also ensure that there is an up-to-date record of patient weight and routine bloods (full blood count and electrolytes).

At this meeting, patients would have an opportunity to discuss any aspect of their CAT management. From our experience, the following issues are of importance to them:

Why they got the CAT.

Why they are on an injectable anticoagulant and not an oral agent.

How long they should be anticoagulated.

How one evaluates whether the clot has gone.

The likelihood of clot recurrence.

Would the treatment for CAT affect their cancer treatment?

For the majority of patients with uncomplicated CAT, the management would require another appointment 2–3 months later to evaluate progress followed by an appointment after 6 months' anticoagulation. This would be the final appointment for patients who no longer have cancer, and it is essential that patients be alerted to the following:

Patients have an ongoing risk of VTE in the future.

The need for risk assessment and thromboprophylaxis at future hospital admissions.

The signs and symptoms of VTE that would warrant medical evaluation.

In those with ongoing active cancer and/or receiving chemotherapy, consideration will be made on a case-by-case basis regarding continued anticoagulation, choice of anticoagulant and the agreed prescriber.21 Follow-up will be determined according to the complexity of their case, clinical condition and access to anticoagulants.

Evaluation of service

Methods

The service was evaluated using the research question ‘What is the impact of a dedicated CAT service on the quality of patient care’ using the following ‘PICO’ (population, intervention, comparator, outcome) framework:

Population: patients with cancer diagnosed with acute VTE.

Intervention: referral to regional CAT service.

Comparator: patient data from initial audit, which established need to establish CAT service.

- Outcome: multiple outcomes, including

- Audit of the uptake of the shared care agreement;

- Patient evaluations through qualitative interviewing;

- Oncologist evaluations through qualitative interviews.

The service was evaluated through a mixed-methods approach, which comprised a prospective audit of clinical data, review of the uptake of the shared care agreement, and qualitative interviewing of referred patients and their referring clinicians following a wider clinician survey, as detailed below.

Audit data were prospectively collected to capture basic patient demographics, cancer type and details of the type of VTE diagnosed. Patients were evaluated to see whether they qualified to be managed according to the shared care agreement, which was then sent to their primary care team. Agreement to participate in the shared care agreement and hence prescribe LMWH in the community was indicated by signing and returning the document. The proportion of returned documents was compared with the proportion of patients receiving community LMWH at the time of the initial audit.

A full description of the qualitative methodology has been reported previously.19 Qualitative interviews are composed of two components: the first being interviews with CAT patients under the care of the CAT service and the second with oncologists who had referred patients. The interviewer (HP), who was from a nursing background, had no prior relationship with participants or declared clinical interest in CAT management. Data from patients were elicited on the following:

Their experience of being diagnosed with CAT

Their experience of the CAT service

How their care could be improved

Data from referring oncologists were elicited on

Their experience of managing CAT

Their views of the CAT service

How their care could be improved.

To facilitate this, questions were open-ended with the use of prompts to probe further into issues, which arose as significant or meaningful to the participant. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also taken. Interviews took ∼40 minutes each. No repeat interviews were necessary; neither did any aspects of transcripts require additional checking with participants.

Analysis

Transcripts were typed into a Word document and uploaded to NVivo V.10 computer software for data management.22 Data analysis was undertaken using a framework analysis (FA). This was considered the most appropriate analytic method to enable a deductive approach towards creating an analytic framework based on the interview schedule, while also allowing room for inductive observations. Analysis was undertaken using the five interconnected stages inherent in FA:23

Familiarisation with data

Identifying a thematic framework

Indexing the data

Charting

Mapping and interpretation.

Results

Over an 18-month period, 457 patients were seen through the CAT service of which 230 (50.4%) were male and 227 (49.6%) female. Mean ages ranged from 21 to 97 years (mean 67, median 68). Precipitants of CAT included chemotherapy (n=384; 84%), surgery (n=14; 3%), radiotherapy (n=3; 0.7%) and acute medical illness (n=3; 0.7%). Patient demographics are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Breadth of cancers reviewed with VTE

| Cancer site | Total N=457 (%) | DVT/PE (N=205/252) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung | ||

| NSCLC | 39 | 8/31 |

| SCLC | 6 | 2/4 |

| Mesothelioma | 5 | 1/4 |

| Total | 50 (11%) | 11/39 |

| Upper GI | ||

| Gastro-oesophageal | 28 | 20/18 |

| Hepatobiliary | 12 | 10/2 |

| Pancreatic | 13 | 7/6 |

| Total | 53 (11.6%) | 27/26 |

| Breast | 86 (18.8%) | 51/35 |

| Gynaecological | ||

| Ovary | 27 | 9/18 |

| Endometrium | 13 | 3/10 |

| Cervix | 4 | 2/2 |

| Vulva | 5 | 2/3 |

| Total | 49 (10.7%) | 16/33 |

| Male urological | ||

| Renal | 20 | 11(5 IVC)/10 |

| Bladder | 10 | 6/4 |

| Prostate | 36 | 20/16 |

| Genital | 5 | 3/2 |

| Total | 71 (15.5%) | 39/32 |

| Brain | 8 (1.8%) | 6/2 |

| Colorectal | ||

| Caecum | 14 | 6/8 |

| Ascending/transverse/descending colon | 40 | 13/27 |

| Sigmoid/rectum/anus | 59 | 21/38 |

| Total | 113 (24.7%) | 40/73 |

| Unknown primary | 9 (2%) | 4/5 |

| Miscellaneous | 18 (3.9%) | 10/8 |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolus; NSCLC, non small cell lung cancer, SCLC, small cell lung cancer; GI, gastrointestinal; IVC, inferior vena cava; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Of 25 eligible patients invited to participate, 20 consented (male=10, female=10). Patients were aged between 53 and 81 years old (mean 68) representing seven different primary cancers , including lung (n=4), colorectal (n=4), breast (n=4), prostate (n=2) and ovarian (n=2). Participants had been receiving LMWH for between 2 and 20 months. All 10 oncologists invited to interview agreed to participate. Their specialist clinical interests represented treatment of a breadth of primary cancers.

We present the results of the audit and interviews together. Data are presented within the context of the quality measures identified from the initial audit (box 1). These include quantitative data from the audit component and qualitative data from patient and clinician interviews.

Inconsistent management of CAT and adherence to guidelines

The initial audit of practice identified that 33 different oncologists and their respective junior medical staff were responsible for the initial and ongoing management of CAT. This resulted in marked variability of practice and suboptimal adherence to clinical guidelines, particularly with respect to correct choice of anticoagulant, duration of treatment and dose prescribing. Following the introduction of the CAT service, for consistency, two dedicated CAT clinicians undertook the management of CAT within the cancer centre.

The establishment of a clear CAT pathway and the shared care agreement ensured that blood tests for safety monitoring were appropriately requested and reviewed. By reviewing patients at 1-month post-diagnosis, all referred patients had their dalteparin dose reduced as per protocol; a further safety net of checking the shared care agreement had been completed and sent to primary care. Furthermore, the pathway ensured that a 6-month review became part of routine practice; all patients were evaluated with respect to continuing anticoagulation or stopping LMWH at this point, dependent on disease status, ongoing treatments, bleeding risk and patient preference.

Variable access to LMWH

Prior to this quality improvement initiative, over 90% of patients with CAT relied on the regional cancer centre to issue LMWH, with only 10% of eligible patients able to access the anticoagulant from their community family physician. Following the introduction of the dedicated CAT service, prescribing within the community of LMWH increased significantly. Overall, 342 (75%) of 457 new cases of CAT were eligible under the terms of the shared care agreement for LMWH prescribing by primary care. Of these, 334 (98%) cases were managed under the shared care agreement, an overall increase in community prescribing by 88%.

Need for information and support

Previous research has reported that patients felt that being given the diagnosis of CAT was often a rushed one, with insufficient information or opportunity to ask questions.19 In the current evaluation, patients felt that the information leaflets provided information and assurances:

The knowledge you get by reading the, all the different literature makes it that much reassuring you know. (Patient 06)

Patients reported being given a ‘thorough’ overview of their condition with respect to their new diagnosis of CAT.

Went right the way through of how the clots were first found, first treated and like. (Patient 02)

Interviewees reported the depth of information given was appropriate for their required level of understanding:

I think they told me what I could understand … I don't need… graphic details and chemical things. As long as they tell me…they think that's what caused it. That's the treatment we're going to give you and it should sort it out and this is what you need to look out for in the future. (Patient 06)

Those requiring more information felt able to ask questions, thereby addressing any other concerns.

Treats you as a person, not a number…any questions you want to ask he's, he's willing to ask. You know he's willing to answer. Um, no he's very very pleasant—it's a lovely clinic. (Patient 7)

Oncologists referring to the CAT clinic also reported that the service offered patients the necessary information and answers to questions as needed.

I think it's a complex field and I think we owe it to the patients to get the best information for them and there are lots of questions that are raised by patients in terms of you know why they've developed a clot, what the options are in terms of treatment and how long they need to be on treatment that I don't feel best qualified to answer. (Oncologist 1)

Lack of consistent specialist expertise

Prior to the introduction of the CAT service, advice was sought from six different haematology teams across four different health boards. Through the introduction of the CAT clinic, variation in practice was reduced by the provision of local advice from one core team. Oncologists considered that the CAT service offered consistent access to clinical opinion on complex specialist issues.

A very important resources in several respects, one is having a single point of access for patients with cancer associated thrombosis, they're often very complex patients with lots of different issues both you know physical and as you can imagine emotional, relating to cancer. (Oncologist 11)

These clinics are a little bit of a godsend in terms of being able to refer to someone for management of more complex questions in the management of people who are risk or who have had um cancer associated thromboembolic events. (Oncologist 06)

Clinicians also reported that it was challenging to keep up to date with the latest guidelines and data within a rapidly changing clinical field.

You know you're getting the right up-to-date correct management without in the middle of a busy clinic where you're thinking of lots of other issues going on you know am I doing this right? And where's the guideline on this and whatever. (Oncologist 08)

Additional benefits

Beyond demonstrating improvement in the four areas of suboptimal practice that were initially identified, additional advantages to introducing the CAT clinic were observed. The dedicated CAT clinics serve as an ideal opportunity for oncology and haematology trainees to learn about the complexities of holistic CAT management within the context of the oncology journey. It has also provided an ideal model for recruitment and follow-up of clinical trials within the field of CAT. The service has also been identified as an excellent training environment for trainee undergraduate and postgraduate medics, clinical nurse specialists and prescribing pharmacists.

Discussion

The management for CAT is becoming an ever-complex challenge, requiring consistent management, availability of information and access to specialist evaluation, when required. Suboptimal CAT management has a negative impact on patient safety, quality of life and expenditure. A dedicated CAT service goes some way to address such challenges with evidence of improvements in consistency of practice, access to specialist advice, access to anticoagulants and patient experience. The service model presented is easily replicable and provides a template for future cancer and haematology services design. To date, two similar services within the UK are being set up to manage regional CAT issues. It is important to acknowledge that this service was developed within the context of the National Health Service; a centrally government-funded UK health system. As such, the service may not be wholly transferrable across differing healthcare systems around the globe. Nevertheless, we believe that there are several transferrable principles, which could reduce variation in clinical practice, waste and harm.

There are limitations to the service model, which we plan to address over time. First, there is scope to develop a more robust level of staffing. At present, two clinicians (SN and NP) provide the main clinical input, which raises capacity issues especially during periods of leave or staff sickness. Ideally, the service would best serve patients at the point of VTE diagnosis, but current resources cannot accommodate this. Second, it could be argued that by establishing a dedicated clinic to address VTE issues, it increases the number of clinic appointments and thus burden for patients. Conversely, some patients have preferred the additional input since their fears around thrombosis recurrence were assuaged by the specialist input. Third, the financial implications of the service have not been fully evaluated. While we have seen a reduction in drug wastage and savings through reducing the dose of LMWH appropriately, the service is yet to undergo a formal health economic evaluation. This would need to consider the additional costs generated from providing staff and clinic space balanced against savings associated avoidable admissions and episodes of harm and the impact on patient quality-adjusted life years.

Finally, there is a risk that a specialist clinic could de-skill generalist oncology healthcare professionals, particularly trainees. To counter this, we have ensured that the clinic functions as a teaching clinic, which accommodates staff each week to gain exposure to the field.

There are several future challenges in optimising the quality of care for CAT patients. One key issue, which needs considering, lies with the ownership of the ‘CAT problem’. Some consider it a haematological problem, which should be managed by haematologists. However, the majority of CAT cases are uncomplicated and the management is straightforward; as with non-cancer anticoagulation that is managed in the main by non-haematology services, so too could CAT, arguably, be taken over in the primary care setting. Others may be of the view that it is an oncological problem. However, we do not ask for all patients with febrile neutropenia to be managed under the infectious disease teams, so it seems counter-intuitive that CAT, another common complication of chemotherapy, should be managed by the haematologist. We have concluded that a pragmatic approach is necessary; so long as there remains a key clinical lead, who has access to support from oncology and haematology when necessary, the specialty with ultimate responsibility is irrelevant. The most important requirement is for a multiprofessional approach delivered by an interested and motivated team that appreciates the physical and psychosocial complexities of CAT within the wider cancer context.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Annmarie Nelson at @annmarie0

Contributors: SN and AN were responsible for study conception and data analysis and wrote the first draft. NP, JS, UM and JD were responsible for data collection and contributed to the manuscript. SL and RA were responsible for data analysis and manuscript preparation. HP was responsible for qualitative interviewing and the analysis of the qualitative data.

Funding: This service evaluation was funded by Tenovus Cancer Care (Grant number: 508972): Registered charity number 1054015.

Competing interests: SN served in the advisory boards of Leo Pharma and Pfizer and in the speakers bureau for Leo Pharma and Pfizer; no honorarium was received. RA served in the advisory boards of Pfizer, Leo Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb and Bayer and in the speakers bureau for Leo Pharma, Pfizer and Bayer.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee South Central—Oxford B.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Noble S, Pasi J. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of cancer-associated thrombosis. Br J Cancer 2010;102(Suppl 1):S2–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble S. The challenges of managing cancer related venous thromboembolism in the palliative care setting. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:671–4. 10.1136/pgmj.2007.061622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Piccioli A et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood 2002;100:3484–8. 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutten BA, Prins MH, Gent M et al. Incidence of recurrent thromboembolic and bleeding complications among patients with venous thromboembolism in relation to both malignancy and achieved international normalized ratio: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3078–83. 10.1200/jco.2000.18.17.3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farge D, Debourdeau P, Beckers M et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. J Thromb Haemost 2013;11:56–70. 10.1111/jth.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2189–204. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e419S–94S. 10.1378/chest.11-2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble SI, Shelley MD, Coles B et al. Management of venous thromboembolism in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:577–84. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013;369:799–808. 10.1056/NEJMoa1302507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The EINSTEIN Investigators Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2499–510. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol 2014;1:e37–46. 10.1016/S2352-3026(14)70018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2342–52. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noble S, Matzdorff A, Maraveyas A et al. Assessing patients’ anticoagulation preferences for the treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis using conjoint methodology. Haematologica 2015;100:1486–92. 10.3324/haematol.2015.127126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahé I, Chidiac J. [Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic recurrence: disregard of treatment recommendations]. Bull Cancer 2014;101:295–301. 10.1684/bdc.2014.1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matzdorff A, Ledig B, Stuecker M et al. German hematologists/oncologists’ practice patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Oncol Res Treat 2014;37:216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheard L, Prout H, Dowding D et al. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in advanced cancer patients: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013;27:339–48. 10.1177/0269216312461678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seaman S, Nelson A, Noble S. Cancer-associated thrombosis, low-molecular-weight heparin, and the patient experience: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:453–61. 10.2147/PPA.S58595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble S, Lewis R, Whithers J et al. Long-term psychological consequences of symptomatic pulmonary embolism: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004561 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noble S, Prout H, Nelson A. Patients’ Experiences of LIving with CANcer-associated thrombosis: the PELICAN study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:337–45. 10.2147/PPA.S79373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabinovich ESS, McCrae K, Bartholomew J et al., eds. Improving outcomes and reducing costs for cancer associated thrombosis using a centralized service: the Cleveland clinic experience. ASH annual meeting. San Diego, California: American Society Haematology, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble S, Sui J. The treatment of cancer associated thrombosis: does one size fit all? Who should get LMWH/warfarin/DOACs? Thrombosis Res 2016;140(Suppl 1):S154–9. 10.1016/S0049-3848(16)30115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewins A, Silver C. Using software in qualitative research: a step-by-step guide. Los Angeles; London: SAGE, 2007:xi, 288. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]