Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the views of general practitioners (GPs) about how they can provide care to homeless people (HP) and to explore which measures could influence their views.

Design

Mixed-methods design (qualitative –> quantitative (cross-sectional observational) → qualitative). Qualitative data were collected through semistructured interviews and through questionnaires with closed questions. Quantitative data were analysed with descriptive statistical analyses on SPPS; a content analysis was applied on qualitative data.

Setting

Primary care; views of urban GPs working in a deprived area in Marseille were explored by questionnaires and/or semistructured interview.

Participants

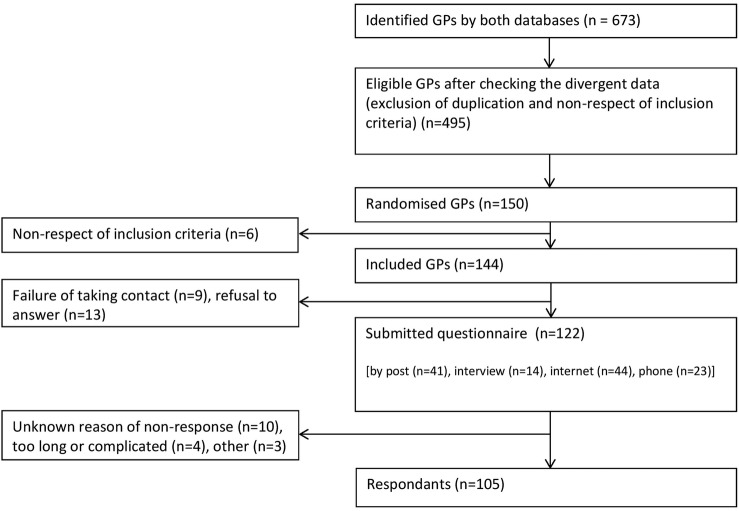

19 GPs involved in HP's healthcare were recruited for phase 1 (qualitative); for phase 2 (quantitative), 150 GPs who provide routine healthcare (‘standard’ GPs) were randomised, 144 met the inclusion criteria and 105 responded to the questionnaire; for phase 3 (qualitative), data were explored on 14 ‘standard’ GPs.

Results

In the quantitative phase, 79% of the 105 GPs already treated HP. Most of the difficulties they encountered while treating HP concerned social matters (mean level of perceived difficulties=3.95/5, IC 95 (3.74 to 4.17)), lack of medical information (mn=3.78/5, IC 95 (3.55 to 4.01)) patient's compliance (mn=3.67/5, IC 95 (3.45 to 3.89)), loneliness in practice (mn=3.45/5, IC 95 (3.18 to 3.72)) and time required for the doctor (mn=3.25, IC 95 (3 to 3.5)). From qualitative analysis we understood that maintaining a stable follow-up was a major condition for GPs to contribute effectively to the care of HP. Acting on health system organisation, developing a medical and psychosocial approach with closer relation with social workers and enhancing the collaboration between tailored and non-tailored programmes were also other key answers.

Conclusions

If we adapt the conditions of GPs practice, they could contribute to the improvement of HP's health. These results will enable the construction of a new model of primary care organisation aiming to improve access to healthcare for HP.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, general practitioners, homeless people, access to health care, mixed methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Using mixed methods permitted us to have a deeper analysis of a complex phenomenon.

We obtained a high quantitative participation rate (73%), compared with similar other studies conducted on general practitioners (GPs).

Qualitative analyses were performed by only one data coder. However, to enhance the accuracy of our interpretation process, we discussed our analysis process and conclusions with different actors (directors of this study, interviewed GPs, external actors) on critical times of the interpretation of data.

During the quantitative phase, to satisfy our operational objectives, we selected only GPs working in the poorest areas of Marseille: extrapolation of our results should be limited to GPs working in urban area, in low-income suburbs and in countries with similar social policies as in France.

Introduction

The number of homeless people (HP) increased by 50% between 2001 and 2012 in France,1 with a similar rate in Europe during the same time frame.2 In 2012, in France, almost 900 000 people lacked personal housing, and almost 3 000 000 lived under poor-quality housing conditions.3 This situation continues to affect a growing number of households and young people.4 European Federation of organisations working with the people who are homeless (FEANTSA) has recently developed a European Typology of Homelessness and housing exclusion (ETHOS), to improve the understanding and measurement of homelessness in Europe, and provide a common language for transnational exchanges on homelessness.5 This typology considers four operational categories of homelessness:

Roofless: people living rough, or in emergency accommodations;

Houseless: people living in homeless shelters or receiving longer term support (due to homeless);

Insecure: people living in insecure accommodations or under threat of eviction;

Inadequate: people living in temporary/non-conventional structures, in unfit housing or under conditions of extreme overcrowding.6

Given the increase of homelessness in the past years, improving the health and social conditions of the homeless has become a priority for European social politics;2 7 it is more important than ever to explore the effectiveness and feasibility of a scheme in which ambulatory general practitioners (GPs; family doctors) play a central role in the primary care for the homeless. Indeed, HP have complex healthcare needs, accompanied by somatic, psychiatric and social troubles.8 9 These people suffer from higher morbidity9–11 and earlier mortality compared with people with stable housing. The average age of death is between 40 and 50 years12 13 and the standardised mortality ratios in high-income countries is typically reported from 2 to 5 times the age-standardised general population.9

They face difficulties in accessing primary care14–16 and go through inadequate therapeutic itineraries, with multiple visits to emergency services.17 18 We know that GPs see a significant proportion of the homeless population: 84% of HP declared that had been consulted by a GP within a year of a study performed in France in 2001;19 a Canadian study shows that 43% of HP had a designated family doctor.20 Family doctors are generally viewed positively by precarious patients which includes HP: they build a confident relationship and are seen as a support for these patients.21 However, GPs are not identified by HP as the first person to turn to for medical assistance whenever they feel ill.22 23

The debate between developing specialised structures for HP or adapting ‘non-specialised’ general practice for HP has not yet been resolved.24 According to a recent literature review, primary healthcare programmes specifically tailored to homeless individuals might be more effective than standard primary healthcare.25 Such programmes could also yield more appropriate care and give the homeless patient a better experience in their care.26 But tailored programmes have many limitations: these programmes (particularly associative or humanitarian programmes) often have insufficient resources to meet such high-level care needs;27 furthermore, such programmes could reinforce the feeling of exclusion of the homeless, and enhance ghettoisation of their care.28

It has been described that GPs felt multiple difficulties in caring for and ensuring continuity of care for precarious or homeless patients. Most of the studies examining views of GPs in France targeted precarious patients or migrants; they mostly used a descriptive approach or targeted ‘specialised’ or ‘involved’ GPs.29–33

We made the hypotheses that, involving ‘non-specialised’ GPs could improve the health of the homeless, by permitting better access and continuity of global care and patient-centred care, if we can adapt their practice conditions for managing HP's care.

Our first objective was to analyse the views of GPs about how they can provide care to HP and to explore which measures could influence these views. Second, we aimed to:

Quantify the exposure of GPs working in a poor area restricted to homelessness,

Describe the knowledge of GPs working in a poor area about homelessness,

Identify and quantify the difficulties and barriers that GPs face in taking care of HP.

Methods

We performed an explanatory sequential study (qualitative, then quantitative, then qualitative phases), in Marseille (France), between November 2013 and March 2015.

Research by mixed methods was recently developed in the healthcare field, especially in public health and primary care.34–37 These methods involve integrating quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis in a single study of one phenomenon, in order to obtain wealth, breadth and depth in the analyses of the data collected.38 39 These approaches rely on a pragmatic worldview and are of particular interest in complex or multidisciplinary areas, like systems organisations, precariousness40 or homelessness.41 42

In the present study, qualitative and quantitative data complement each other:

Phase 1 was qualitative and aimed to get a better understanding about the way GPs care for the homeless. For this phase we recruited GPs who were involved with the homeless. Our results highlighted relevant propositions to construct a closed questionnaire for phase 2.

Phase 2 aimed to quantify exposure, knowledge, difficulties and involvement of GPs with a standard practice in the care of the homeless. We noticed divergent opinions about how much these GPs could contribute to the health of the homeless. It thus appeared relevant to understand why these GPs had divergent opinions, and why they seemed to be different from the involved GP's opinion.

That is why phase 3 aimed to characterise the views of GPs about their role in care giving to the homeless, and to explore deeper which factors could influence these views.

Last, but not least, we propose a deeper reflection by simultaneously discussing the results of both phases.

Figure 1 shows a description of our protocol, explained below.

Figure 1.

Study protocol. Orange—phase 1, violet—phase 2, green—phase 3. GP, general practitioner.

Phase 1: building hypotheses with GPs involved in care giving for HP (qualitative)

Preliminary assumptions

We aimed to explore and understand practices and knowledge of GPs who already have experience in managing care for HP. At this point, we thought that GPs could be a lever to improve the health of HP. Our questions to explore the views of doctors were built on the basis of a few elements from the literature and first exchanges with several GPs particularly involved in the care of the homeless. The researcher (who performed the interviews and analysis) had no experience in taking care of HP in France, before this phase.

Population and sampling

This phase targeted the GPs who were considered as ‘involved’ with the homeless: GPs who were working in specialised centres for HP or precarious patients, or ambulatory GPs who considered themselves involved in and/or exposed to homelessness. First the GPs were identified working in specialised care centres for precarious or HP. Three of them had already been identified by HB to be particularly involved with the homeless, who had established contact with them before the construction of this protocol. We, then, extended the sample using a ‘snowball’ method. This method is justified when we want access to a specific population that is hard to find and to maximise the chance of acceptance.43 We ensured the diversity of our sample by collecting data on age, sex, characteristics of GPs practice and patients. We stopped the inclusion when saturation of data had been reached.43 We did not perform repeat interviews. GPs were recruited from November 2013 to February 2014.

Data collection

Semistructured interviews explored views of ‘involved’ GPs about:

Health, access to healthcare and continuity of care for homeless people;

Care giving by GPs for homeless people;

Recovering medical histories and using shared electronic medical records for the HP (we did not develop this last part on this research; see online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2016-013610supp1.pdf (741.6KB, pdf)

The same investigator (principal author of this article, master thesis student and resident in general practice at this time and who was presented as such) contacted the GPs first by phone, agreed to an appointment with them and then conducted the interviews in places chosen by each GP. The interviews were conducted after two pilot tests. They were conducted face-to-face, recorded (only audio) and then fully transcribed. Field notes were made during and after the interviews, about attitudes of GPs, but not recorded information and the place of the interviews. All the interviews were anonymised as soon as they were concluded. An information letter was given to each GP and a written consent was obtained for publishing the results.

Analyses

We performed a content analysis on the transcriptions, using N-Vivo V.10. This software is useful for qualitative analyses, enabling enhanced validity and rigour in the qualitative analysis process.44 Owing to time and financial constraints, only one data coder performed the analyses (MJ), but all the steps of the coding were followed and approved by HB. We did not return the transcripts to the interviewed GPs, but we asked their opinion about our interpretation of data (during a meeting where we shared the interpretation of the first five interviews, asking for their feedback when results had been written).

Phase 2: describing views of a representative sample of ‘standard’ GPs (quantitative)

We performed a descriptive, cross-sectional study.

Population and sampling

Phase 2 targeted GPs having a standard practice of family medicine in France. They could be exposed or involved in the health of HP, or not. In order to make the script clearer, we named these GPs ‘standard GPs’. We included GPs who were working in the centre or in the northern part of Marseille (the areas which are most affected by homelessness), in private offices or health centres, working alone or in groups. Two public databases of GPs allowed us to identify all GPs who could meet the inclusion criteria. GPs with divergent information in these databases were contacted before randomisation to confirm their eligibility. We then randomised 150 GPs. They were recruited from June 2014 to July 2014.

Data collection

We relied on our results from phase 1 (especially here: thematic about the perceived difficulties), and data from the literature, to prepare the questionnaire for phase 2. We tested the questionnaire on two GPs before the real application. The questionnaire explored GPs' general characteristics, exposures, knowledge and levels of difficulties in care giving and views about how much they can contribute to the primary care of HP (see online supplementary file 1). In order to increase the response rate, we proposed four modes of answer: phone, post mail, internet (with a secured link on SurveyMonkey) or face-to-face. An information letter was given to each GP.

Analyses

We performed descriptive analyses with SPSS V.20, with means and confident intervals. Views of GPs were explored using the Likert scale. The main variable was the opinion of GPs about how much they could contribute to the care of HP.

Phase 3: exploring views of ‘standard’ GPs and understanding which conditions could influence their views (qualitative)

Preliminary assumptions

At this point we had more specific assumptions, given the results of phases 1 and 2. We aimed to get a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. We wanted to explore how the involvement and the effectiveness of GPs about taking care of HP should depend on organisational or individual factors (linked to patients and/or health professional). We expected to find solutions which could be relevant for GPs when they treat HP. The researcher had work experience in two centres for the socially deprived patients before this phase.

Population and sampling

Phase 3 targeted ‘standard’ GPs as defined before. GPs were recruited from the list of those who responded to the questionnaire in phase 2, between December 2014 and March 2015. We used a quota sampling method to have a diversity based on age, sex, type of exercise (private/employed /mixed), having a secretariat or not, working alone or with other GPs at office and exposure to HP in their practice. We stopped inclusion when saturation of data had been reached. We did not perform repeat interviews.

Data collection

We performed semistructured interviews, exploring the views of GPs about: healthcare giving to HP, barriers and difficulties in achieving their contribution (see online supplementary file 1). The same investigator (principal author of this article, doctoral student and resident in general practice at this time, and who was presented as such) contacted the GPs first by phone, agreed to an appointment with them, then conducted the interviews in places chosen by each GP. The interviews were conducted after two pilot tests. They were conducted face-to-face, recorded (only audio) and then fully transcribed. Field notes were made during and after the interviews, about the attitudes of GPs, not recorded information, and the place of the interviews. All the interviews were anonymised as soon as they were concluded. An information letter was given to each GP and a written consent was obtained for publishing the results.

Analyses

We performed an inductive thematic content analysis, using N-Vivo V.10. Owing to time and financial constraints, only one data coder performed the analyses (MJ), but all the steps of the coding were followed and approved by HB. We did not return the transcripts to the interviewed GPs (due to a confidential policy), but we returned the results when they were written, before publication.

Ethics

All the parts of this study were registered on CNIL (French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties).

Results

Phase 1: results from interviews on ‘involved GPs’

Characteristics of the sample and interview

We interviewed 19 GPs, mostly at their office (among the others, 1 was performed at the GP's residence, 1 in a public area and 2 in the public health department). We obtained data saturation on the 18th interview, confirmed by the 19th. The average duration of the interviews was 1 hour. Five GPs refused to participate (lack of concern of homelessness by two GPs and lack of time for interview by three of them). For five other GPs, we could not obtain first contact. The sample was diversified by age, sex, type of exercise and structure of the exercise. Most of them13 were either employed or had mixed practice. None of them declared receiving any patient with a high or very high social level (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ‘involved GPs’ (phase 1, n=19 GPs)

| ‘Involved’ GPs' characteristics | Effectives |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <40 | 6 |

| 40–50 | 2 |

| 50–60 | 4 |

| >60 | 7 |

| Sex category | |

| Men | 11 |

| Women | 8 |

| Current type of exercise | |

| Private | 6 |

| Employed | 10 |

| Mixed | 3 |

| Experienced structure for work* (multiple choice) | |

| Private medical office | 11 |

| Private medical office insuring a medical permanence | 3 |

| Health centre | 3 |

| Specific centres for precarious or homeless people | 10 |

| Other | 9 |

| Social level of patients seen by GPs (multiple choice) | |

| Very low | 13 |

| Low | 13 |

| Medium | 8 |

| High | 0 |

| Very high | 0 |

*Structure for work: where GPs were working or have already worked.

GP, general practitioner.

Coding tree

We developed three main categories on this phase (see online supplementary file 2):

Access and continuity of healthcare for the HP;

Sharing of medical information when having medical record of the HP;

Care for HP by GPs.

bmjopen-2016-013610supp2.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

This article discussed the main themes on this last category. The themes were derived from the data.

Three categories of difficulties identified in the care of the homeless

We identified three categories of difficulties for GPs in providing care to the homeless (table 2):

Personal difficulties, which included practical questions (money/time/reception/management of consulting) and emotional or psychological consequences for the doctors while they care for HP;

Difficulties with care management: the care management was perceived as complex and heavy. GPs explained these difficulties mostly by: multiple issues for patients, difficulties in knowing medical data and overinvestment of doctors;

Difficulties in interacting with the homeless patients (physical appearance of HP, communication and relation with the patient, comprehension of the patient).

Table 2.

Difficulties intented by ‘involved’ GPs about taking care of a homeless in general practice

| Categories of difficulties | Associated themes (arguments) | Example of verbatim transcript |

|---|---|---|

| Personal for GPs (16 GPs/108 verbatim) | Emotional/psychological (13 GPs, 43 verbatims) (Uselessness/frustration/discouragement/stress/weakening doctor status/discomfort/wearing out) |

“Being in a repeated failure without capacities to analyse this…Is hopeless. If we can make sense of it, working on it with partners, psychologist and social workers, it is a little bit different.” “They deprive doctors from their power.” “Working with homeless is a school of frustration.” |

| Practical (14 GPs, 65 verbatims) (Money/time/reception/management of consulting) |

“For a liberal doctor… it's complicated to manage. A doctor has the duty to ensure a secure place to receive other patients.” “I cannot do that in private. I cannot…in fifteen minutes.” |

|

| Care management (18GPs/60 verbatim) | Complexity (11 GPs, 30 verbatims) (Multiple issues/context of homelessness/means required) |

“It's hard to put back these patients on common primary care. Even if you open social rights for them, they require more time, in terms of understanding, or because of multiple pathologies. That's why doctors have difficulties to care for them.” |

| Importance of care management required (5 GPs, 10 verbatims) (Over investment for doctors/lack of autonomy for patient) |

“But I cannot take this patient and go with her in hospital, right?” (About a pregnant patient who need to have a follow in hospital because of risk pregnancy) | |

| Retrieving medical information (16 GPs, 20 verbatims) | “So here, this is very important, we often do not know, we know nothing.” | |

| Interaction with homeless patients (14 GPs/34 verbatim) | Physical appearance (10 GPs, 15 verbatims) | “When they can't physically be like a person who has a home, already they are seen differently.” |

| Communication/relation (8 GPs, 11 verbatims) | “When I treat a homeless person, sometimes I see from him a reaction to which I didn't expect.” “We have difficulties to communicate with these persons, because of language barrier, but also because they are big outsiders.” |

|

| Comprehension of patient (5 GPs, 8 verbatims) (Observance, different views) |

“They don't do what we want them to do…There are resistances from them, associated with social problems or…(other problems). Doctors can misinterpret that.” |

GP, general practitioner.

Personal obstacles and difficulties in healthcare management were identified by some other GPs (respectively, 18 and 16 GPs), than the difficulties in interacting with the homeless patients (14 GPs). When personal dilemmas were identified, they took an important part in the discourse of GPs (108 verbatims), showing that it had important consequences on their view about how they treated the HP. Issues about managing social problems of the patients (social rights, life context and social condition, social rehabilitation) weren't identified as a category of difficulties during the analysis of the involved GPs' speech. This was expressed by the GPs as a limitation for the HP to have access to healthcare, or staying in a stable follow-up relationship.

All GPs spoke of their limitations and about how to correctly manage HP. They described these limitations mostly as experts rather than express their difficulties. Here, the first argument concerned limitations about coordination and follow-up (limitations due to the life context of homeless patients, unstable follow-up relationship, inappropriate answers of ‘standard’ GPs, difficulties to identify supports as specialised centres, limitations of relation between outpatient care and institutional care, lack of information about the medical history of the homeless patients, limitations due to their private practice or common law system). Eight GPs expressed that a proper follow-up was most of the time impossible for chronic diseases.

Strengths of GPs and conditions to improve access and continuity of care for the homeless

GPs as one of the solutions to improve access and continuity of care for the homeless

We asked the involved GPs about which of the solutions could improve the access and the continuity of care for HP. Family doctors or common law system were perceived as one of the solutions by 13 GPs (on the 19 interviewed). Fifteen GPs stated that outpatient treatment could have a positive impact on HP.

They advanced three main arguments:

GPs can prevent and/or get out of precariousness:

It seemed that the contribution of GPs, as family doctors, could be really important when the patients are ‘on the top of the slide’ (as one GP expressed in the focus group performed after the first analyses). GPs are in a good position to know life context and environment of their patients, so that they are the best ones to screen vulnerability. The involved GPs mostly empowered themselves in preventing precariousness of their patients. Some expressed that GPs could help HP to get back to a social stability, to come back in the ‘system’: “I’m sure…with health, taking into account health, it can be a way to get into rehabilitation and the return to socialization” said one GP (working in ‘Permanence d'Accés aux Soins de Santé (PASS) psychiatrique’, a specialised structure for the access to care for precarious people with psychiatric troubles), “we (the GPs) are the entrance of the system…we guide into the system” said another GP (a GP who had worked as a family doctor and was involved in medical consultations for HP into an emergency accommodation).

GPs as a solution for reducing stigmatisation of HP:

Much more than a simple return to common law system, GPs explained that being received in a common medical office, or experiencing hospitality and respect in healthcare encounters, can improve the self-esteem of HP. It can become an integral part of care for HP. For example, a GP who works in a private medical office where he received some HP and also in a structure for treating patients of addictions, explained: “I think that it can be gratifying to be in a waiting room…with a mother and her baby, a little old lady and many other average persons”.

GPs are a strength for beginning and manage a stable follow-up:

GPs felt they could create trust with homeless patients. This trust, combined to positive attitudes, was perceived as a solution to create a positive therapeutic relationship. Furthermore, GPs were described as referent, who can build a solid network around the patient, which can help to provide global care. GPs explained that these elements could permit a better use of care and a more stable follow-up relation for HP. However, they recalled the limits of the management of HP's healthcare for succeeding in the private activity.

A significant proportion of GPs (7 out of 19) spontaneously expressed that working with HP had a favourable impact on them too. It could be for some of them a necessary activity, for others a type of care that suited them better, a challenge they took pleasure to meet, a better relationship or a sense of accomplishment.

Some adaptations are necessary when taking care of HP

Two major adaptations appeared necessary to succeed in improving access and continuity of primary care for HP:

First, a necessary adaptation for GPs to take care of HP:

All the ‘involved’ GPs (19 GPs) explained in many fields how they must adapt their practice, behaviour or care setup if they want to be efficient in receiving and treating HP. We identified four categories of adaptation. Three of them reflected the difficulties identified by GPs:

Practical setup (19 GPs, 29 verbatim): by proposing an immediate response with no appointment for consultations, using a secretary at office, or practising the ‘third-party payment’ (which means that GPs are directly paid by insurance so that patients need not pay for the consultation);

Interaction with homeless patients (19 GPs, 175 verbatim): by adapting GP's behaviour when treating HP (showing respect and empathy, building a trusting relationship…), understanding differences in behaviour of homeless patients or taming the patient;

Management of care (19 GPs, 175 verbatim): by adapting the objectives of care, or adapting the practice to homeless patient life, with an active outreach strategy (‘going to’ the patient).

The fourth category concerned learning about specificities of precariousness or homelessness (6 GPs, 12 verbatim).

- Second, the importance of a global, medicopsychosocial, management:

In the discussions with 15 GPs, social issues were more important than medical questions when they treated homeless patients, so that the social management became caring for the homeless. Furthermore, 14 GPs explained how the social workers played an important role, to ensure access to healthcare, but also to treat other social problems of the homeless (food, housing). Furthermore, the importance of a multidisciplinary care management was expressed by 13 GPs. They explained here interest of working with a team of different professionals, including street teams, social workers and psychologists. Eight GPs expressed the need to build a network throughout the city to connect professionals who practice with homeless.

Phase 2: results from ‘standard’ GPs who worked in area concerned by homelessness

Characteristics of the sample

Among the 150 doctors randomised, 6 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and 38 did not respond to the questionnaire. One hundred and five questionnaires were usable; hence, the response rate was 73% (figure 2). Most of the included GPs were older than 50 years (72%), and were men (74%). Only 9% of them had an employed or mixed practice. Our sample was of a similar age and structure of practice profile to the 2014 average mix of GPs working in medical private office or health centres in France.45 However, there were fewer women (26%) in our sample in comparison to the average (35.4%) (p=0.04; table 3).

Figure 2.

Flow chart (‘standard GPs’, phase 2). GP, general practitioner.

Table 3.

Characteristics of GPs who responded to the questionnaire and comparison with French GPs (phase 2 )

| GPs included (n=105) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPs’ characteristics | French GPs in 2014 (medical private office and health centre)* | Effectives (%) | p Value |

| Age (years) | |||

| < 40 | 9397 (14.0%) | 12 (11.4%) | 0.73 |

| 40–50 | 12418 (18.5%) | 17 (16.2%) | |

| 50–60 | 25121 (37.5%) | 41 (39.0%) | |

| >60 | 20000 (29.9%) | 35 (33.3%) | |

| Sex category | |||

| Men | 43209 (64.5%) | 78 (74.3%) | 0.04 |

| Women | 23727 (35.4%) | 27 (25.7%) | |

| Type of exercise | |||

| Private | – | 96 (91.4%) | |

| Employed/mixed | 9 (8.6%) | ||

| Structure for the exercise | |||

| Medical private office | 64302 (96.1%) | 103 (98.1%) | 0.28 |

| Health centre | 2634 (3.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | |

| Number of years passed in the structure | |||

| <5 | – | 10 (9.5%) | |

| 5–10 | 14 (13.3%) | ||

| >10 | 81 (77.1%) | ||

| Number of GPs in the structure | |||

| Individual exercise | 30869 (46.1%) | 45 (42.9%) | 0.56 |

| Grouped exercise | 36067 (53.9%) | 60 (57.1%) | |

| Secretariat | |||

| No | – | 61 (58.1%) | |

| Yes | 44 (41.9%) | ||

| Number of patient seen by day | |||

| <20 | – | 30 (28.6%) | |

| 20–30 | 43 (40.9%) | ||

| >30 | 32 (30.5%) | ||

| Medium social level of patients currently seen | |||

| 1 (very low) | – | 7 (6.7%) | |

| 2 (low) | 26 (25.0%) | ||

| 3 (middle) | 65 (62.5%) | ||

| 4 (high) | 6 (5.8%) | ||

| 5 (very high) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

*Data concerning exercise of French GPs on 1 January 2014 (DREES).45

GP, general practitioner.

Exposure and knowledge of ‘standard’ GPs about precarious patients

A large majority of the GPs (79%) declared having already received a homeless at office (table 4). These GPs received very few HP (almost never or few often for 79.2% of them). If they were mostly exposed to moderate homelessness (insecure or inadequate housing for 62.8% of the GPs), a significant proportion of them (37.1%) were more likely to also receive roofless or houseless patients.

Table 4.

Exposition and knowledge of ‘standard’ GPs about homelessness

| All GPs (n=105) | Effectives (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you already received a homeless at office? | |

| Yes | 83 (79.0%) |

| No | 19 (18.1%) |

| Don't know | 3 (2.9%) |

| GPs who have already received a homeless and responded part 2 of the questionnaire (n=82) | Effectives (%) |

| How often do you receive homeless people? | |

| 1 (almost never) | 37 (45.1%) |

| 2 | 28 (34.1%) |

| 3 | 11 (13.4%) |

| 4 | 3 (3.7%) |

| 5 (daily) | 3 (3.7%) |

| Which categories of homeless patient do you receive more often? | |

| Roofless | 4 (5.7%) |

| Houseless | 22 (31.4%) |

| Insecure | 33 (47.1%) |

| Inadequate | 11 (15.7%) |

| Have you already attended a formation about precariousness? | |

| Yes | 5 (6.1%) |

| Non | 77 (93.9%) |

| Do you know the EPICES* score or other tools to measure precariousness? | |

| Yes | 1 (1.2%) |

| No | 81 (98.8%) |

| Are you aware of any accommodation for homeless people in Marseille? | |

| Yes | 56 (68.3%) |

| No | 26 (31.7%) |

| Do you know what is a PASS†? | |

| Yes | 23 (72.0%) |

| No | 59 (28.0%) |

| What is the telephone number of SIAO‡? | |

| Correct answer | 35 (43.2%) |

| Wrong or unknown answer | 46 (56.8%) |

*EPICES score is a valid screening tool for precariousness, which explore various dimension of precariousness by 11 questions and can be used in general practice.46 47

†PASS is a social or medicosocial centres developed in order to facilitate access to care for socially deprived persons. These centres offer free medical aid for primary care and social support for these people in public hospital.

‡SIAO is an integrated area-based service for the reception and orientation of people facing homelessness. They were created in France in each department with the France's national strategy 2009–2012.

EPICES, Evaluation de la Précarité et des Inégalités Sociales de Santé dans les Centres d'Examen de Santé;GP, general practitioner; PASS, Permanence d'Accés aux Soins de Santé; SIAO, Service Intégré Accueil Orientation.

Few GPs (6.1%) underwent a specific training about precariousness. Most of the ‘standard’ GPs had a low level of knowledge about homelessness and precariousness: only 1.2% of the sampled GPs knew the EPICES (Evaluation de la Précarité et des Inégalités Sociales de Santé dans les Centres d'Examen de Santé) score, which is a standard score in France for screening precariousness in general practice,46 47 28% of GPs knew the PASS system, which is the institutional system to ensure medical care and social help for people with no access to care in France; and 43% of GPs knew the telephone number for emergency housing service (Service Intégré Accueil Orientation; table 4).

Difficulties perceived by GPs in caring for HP

Social management when caring for HP emerged as the greatest difficulty for ‘standard’ GPs when treating the homeless (mean=3.95/5±0.98, on a Likert scale between 1 (no difficulty) and 5 (very high difficulties; table 5). Other significant difficulties were related to (in decreasing order): retrieving medical information (mean=3.78/5±1.05), management of patient's compliance (mean=3.67/5±0.99), loneliness in practice (mean=3.45/5±1.22) and excessive time necessary for consultation (mean=3.25/5±1.12; table 5).

Table 5.

Quantification of the levels of difficulties felt on Likert scale by ‘standard’ GPs who have already received homeless patients, when they take care of these patients (n=82 GPs)

| Difficulties | Mean* | SD | IC 95 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical | |||

| Time necessary | 3.25 | 1.12 | (3.00 to 3.50) |

| Patient's reception | 2.60 | 1.29 | (2.31 to 2.88) |

| Financial (volunteer work) | 2.19 | 1.25 | (1.91 to 2.46) |

| Care management | |||

| Complexity | 3.00 | 1.17 | (2.74 to 3.26) |

| Retrieving medical information | 3.78 | 1.05 | (3.55 to 4.01) |

| Social management | 3.95 | 0.98 | (3.74 to 4.17) |

| Interaction with patients | |||

| Patient's compliance | 3.67 | 0.99 | (3.45 to 3.89) |

| Patient's behaviour | 2.78 | 1.21 | (2.51 to 3.05) |

| Patient's physical appearance | 2.74 | 1.28 | (2.46 to 3.02) |

| Emotional | |||

| Frustration of GPs | 2.80 | 1.17 | (2.55 to 3.06) |

| Depreciation of GPs | 1.69 | 1.00 | (1.46 to 1.91) |

| Loneliness in practice | 3.45 | 1.22 | (3.18 to 3.72) |

*Mean of GPs’ answers on Likert scale (between 1=none and 5=very high difficulties).

GP, general practitioner.

Divergent answers regarding how GPs could contribute to the care of HP

Views of GPs about how much they could contribute to the HP care were divergent, with a mean of 3.05/5±1.04 on Likert scale (between 1 for ‘not at all’ and 5 for ‘very much’). Some GPs gave explanations for this question: a significant part of them spoke about insufficient means, or the necessity to adapt the health system and primary healthcare organisation for permitting such a contribution for ambulatory GPs. Only two of them said that it was not a question concerning GPs or that some GPs would not accept to contribute because of their personal position.

Phase 3: explaining ‘standard’ GPs’ views about their contribution to healthcare for HP (qualitative analysis on a subsample of ‘standard’ GPs)

Characteristics of the subsample and interview

We included 14 GPs, who were differentiated by sex, age, type of practice, number of doctors in the office, secretary and having, or not, and received a homeless patient in the past. Interviews were mostly conducted at their offices (except one which was passed in a public area). The average duration of the records was 29 min. GPs who refused to participate explained that their refusal was because of lack of time for the interview. We obtained data saturation on the 13th interview, confirmed by the 14th. One GP delayed the interview and was not included because data saturation had been reached.

We identified four profiles of GPs:

GPs regularly involved in and who had an experience in the care management of homeless (two GPs): they self-reported a good knowledge of homelessness and many relations to coordinate the care of homeless patients. They recruited homeless because of this profile.

GPs who were exposed to homelessness and felt concerned about the problem (three GPs): they worked on particular deprived areas, or had mixed activities concerning homelessness or precariousness.

GPs who were not exposed to homelessness but felt concerned (four GPs): they worked on suburb(s) areas and were not exposed to the roofless. They reported that they almost never received homeless patients without explaining why.

GPs who were not exposed to homelessness and had negative views (five GPs): they worked also in suburban areas. They showed negative attitudes and views which could prevent homeless patients from consulting again these doctors.

Coding tree

We developed four main categories on this phase (see online supplementary file 2):

Health system organisation;

View of GPs about HP;

Role of GPs when caring for HP;

Care for HP by GPs.

The themes were derived from the data.

Conditions for ‘standard’ GPs to be involved in treating the homeless

The qualitative analysis showed that maintaining a stable follow-up was a major condition for GPs to contribute effectively to the care of HP (11 GPs, 26 verbatim; figure 3):

For some GPs, the presence of stable follow-up was the reason why they could contribute to the care of HP, as shown in this extract: “Yes [answering the question if GP could contribute, bring something positive to the health of homeless people], because most of the time I see, as I said, finally they come back […] They come back to see me […] they choose me as a family doctor”.

For other GPs, a stable follow-up was the most cited condition to enable participation in the care of HP: “it would be necessary to develop a kind of coercion which led them to a little loyalty. Here we can build something”.

The last GPs cited failure of follow-up to argue why they could not contribute to the care of HP.

Figure 3.

Identified factors to influence the odds of building a stable follow-up of homeless patients (interview with ‘standard’ GPs, phase 3). GP, general practitioner; HP, homeless people.

As shown in figure 3, we identified three main factors that influenced the possibility of maintaining a stable follow-up: attributes of patients, care management conducted by GPs and health system organisation.

The factors that we identified in the speech of GPs were better linked to GPs' care management and to healthcare organisation, than to homeless patients themselves.

Concerning health organisation: social management, multidisciplinary practice on a team, backing and active outreach were mentioned as conditions to enhance the follow-up of homeless patients; social issues posed the greatest barrier for these GPs (access to social rights, and housing).

Concerning GPs: geographic proximity, attitude, trust in the relationship, education on health and adaptation in the care giving by GP were mentioned as conditions that could enhance the follow-up of homeless patients; negative attitudes and lack of active outreach for the homeless patients were the most barriers to the success of follow-up identified.

Having a stable follow-up relationship seemed to enhance views and attitudes of GPs. Success of a trust-based relationship and recovering social rights were all noted as the elements of a virtuous circle created by the follow-up.

Two others conditions were identified for GPs to effectively contribute to the care of HP:

Working in close relation with social workers (9 GPs, 12 verbatim);

Adaptation of GPs with better knowledge about homelessness (3 GPs, 4 verbatim).

These conditions seemed also linked to the success or failure of a stable follow-up as shown on figure 3.

Discussion

Main result: GPs could effectively contribute to the care for HP if we adapted the conditions of their practice

In this study, almost 80% of GPs who worked in the centre or the northern part of Marseille had already been exposed to homeless patients. Analysing the three parts of this study, we showed that conditions of GP's practice were a major factor which influenced the views of GPs regarding how they could contribute to care giving for HP. Indeed, in the quantitative part, ‘standard’ GPs felt the most difficulties in the care giving for the homeless due to: social management, retrieving medical information, management of observance of homeless patient, loneliness in practice, time necessary for consultation and complexity of care management. All these items could be improved by a better organisation of primary care, coordination and organisation of general practice. A study performed in the UK in 1996 has showed similar results, of the social problems as the first ones perceived by GPs when they cared for HP (90% of GPs agreed), followed by lack of medical records, complex health problems and alcohol or substance misuse.32 We did not directly ask the ‘standard’ GPs about substance misuse during the questionnaire, but the behaviour of homeless patients was not perceived as an important difficulty. However, during the phase 3 (qualitative), when ‘standard’ GPs perceived difficulties concerning patients with problems of substance misuse, it was a strong barrier for them to accept these patients. In the qualitative analysis performed on ‘standard’ GPs, we identified that a stable follow-up relationship between homeless patients and GPs was a central condition for GPs to be pertinent and effective in the care management of the homeless. This condition seemed to be closely linked to the characteristics of the health system organisation or characteristics of GPs' activity and behaviour than the patients themselves. After analysing the discourse of ‘involved’ GPs, we found that ‘involved’ GPs viewed the follow-up as something difficult to obtain, but a responsibility and challenge for them in the care giving for the homeless. So we can expect to improve this follow-up by adapting the conditions of practice for GPs. We need more data to explore if the conditions of practice influenced GPs or if the view and positions of GPs led them to choose this specific kind of practice. It would be interesting to complete these results by a study comparing a group of employed or mixed GPs and a group of private GPs. We also have to consider the differences between social aspects experienced by GPs and HP. It has been described that being recognised as different members of social classes, or cultural differences (called by E Carde48 ‘differentiation’), can influence the difficulties or views of health professionals about taking care of patients.49 50 We asked the involved GPs why they had engaged themselves in homelessness: only two of them spoke about their social origin (worker class) or familial past (alcohol addiction of his father). They mostly expressed a personal involvement due to moral values, and/or generated by their professional career. However, we did not have more details about social origin of the GPs who were interviewed, in phase 1 or 3, or who answered the questionnaire.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

The choice of a mixed-methods design was justified here by the complex and sensitive nature of our research object. With the integration of multiple perspectives of different actors (GPs who were involved in homelessness and GPs with a standard practice) and quantitative and qualitative data collection, we aimed to provide a more complete and rich understanding of a phenomenon.36 38 51 52 Furthermore, the identification of areas of convergence or divergence among results can increase the rigour of the study and usefulness of the findings.53 Our ‘step-by-step’ process permitted to obtain a complete, rich and credible picture about the question of managing HP by GPs.54

Qualitative methods involve some subjectivity of the investigator during the analysis data process. Owing to financial and time constraints, we were unable to perform the analyses with another investigator. In order to limit the risk of irrelevant interpretations,55 the thematic coding was shared between the researcher and director of this research on each important step of its transformation; here, the use of a software (N-vivo) enhanced the rigour of the analyses.55 56 To enhance the rigour of our interpretation process, we discussed our conclusions with the participants of this research (interviewed GPs) at different times: during a meeting after the analysis of the firsts five interview for phase 1 and asking for a feedback about written results of phases 1 and 3. The reflexing process of the researcher was improved by listening to opinions and experiences of other external participants during the whole process of data collection and analyses and an involvement in a charitable association (Médecins du Monde) as a participant observation process throughout the analysis of phase 1. The intellectual effort and the multiple interpretations of actors were written as much as possible by the researcher.57 58 This progressive and interactive process has improved the method and the understanding of the results of each phase.

For the quantitative part, we chose to include GPs who worked in the suburbs which were more affected by precariousness, in order to address the problem on a concerned population and to follow a local interventional programme for the homeless in Marseille.59 The sampling process was rigourous so we can consider our sample to be representative of GPs working in the suburbs affected by precariousness. That can explain why our sample was not completely representative of French GPs: we do not want to extend these data to all GPs, but only to GPs who work in urban area and in low-income suburbs. We obtained a good level of response (74%) if we compare to similar design performed on close themes.31 32 There was no difference between respondents and non-respondents concerning work area and sex (the only data we had for non-respondents). However, we can suspect that GPs who did not answer the questionnaire had more negative views about HP and GPs role in their care. If the data collection had been diversified to improve the proportion of respondents, it could influence the response of GPs, in particular when it was conducted ‘face-to-face’. Using a standardised questionnaire and the same investigator should have reduced this limit.

Operational propositions for an efficient medical care in primary care for HP: how we can adapt the ambulatory condition of GPs' exercise

Regarding our results and data from other studies, we propose some specific solutions for GPs to improve access and continuity of care for the HP.

A grouped and multidisciplinary practice

The importance of a multidisciplinary and integrated approach (proposing, eg, housing on the same time than healthcare) for HP have already been described.25 60 Concerning specifically GPs: GPs' attitudes towards HP has been identified on a qualitative study as the major barrier to give access to primary care for HP.61 As it has been described, the behaviour of health workers with the homeless was modified when they worked in a multidisciplinary structure,62 we can expect that this kind of adaptation could be beneficial to personal experience of care management for GPs63 and enhance positive attitudes which can lead to more convenient access to care for the homeless.

Associate medical, social and psychological care, with the development of closer relations between GPs and social workers

Our study showed how social issues become a part of care when GPs have to care for HP. Other studies performed on precarious patients revealed the necessity to develop closer relationships between health workers and social workers,30 so we can expect that it is the same need when caring for homeless patients. In France, ‘microstructures’ have developed this multidisciplinary scheme, in general practice offices that integrates the presence of psychologist and social workers in a private medical office for 2 hours per week. These programmes concerned drug-addicted patients who lived in highly precarious conditions. This scheme enhanced access and continuity of care concerning prevention and chronic diseases for the patients who were included.64 65

Improving knowledge of GPs about precariousness and homelessness

In qualitative analyses, the lack of knowledge of GPs about social questions and the lack of experience of GPs in homelessness seemed to influence their behaviour and capacity to adapt their management for HP. A lack of knowledge about precariousness has already been highlighted in other French studies, where GPs identified training needs for multidisciplinary approach and social questions.31 66 67 The necessity to improve knowledge and develop training of GPs about homelessness has also been discussed by Riley et al24: for them, it is one of the major solutions (with support of primary care trusts) to make the ‘full integration of HP into mainstream primary care services’ occur. Both ‘standard’ and specialised GPs experienced difficulties when caring for the homeless, struggling to maintain a stable follow-up relationship. The ‘involved’ GPs tended to have more positive views on the homeless patients, they showed a better control of the complex situations of these patients and saw a successful follow-up relationship more as the responsibility of GPs to make it possible than as a condition for GPs to take care for HP.

Considerate non-medical time in remuneration of GPs

It is necessary to adapt the remuneration mode for private GPs, so that they consider the complexity of the care giving for homeless. This way they would be able to spend more time for active outreach, patient support, developing a care relation and coordination of care. These adaptations are described as solutions to improve the use of health system by the homeless, by enhancing care requests, providing them greater self-confidence and enhancing the trust of the homeless patients in the healthcare system.68

Develop a partnership between tailored and non-tailored systems

Lack of knowledge and difficulties for GPs to communicate with social or other specialised centres has been described in a French mixed study performed on GPs about precarious patients.31 Lester and colleagues, analysed the limits of tailored centres for the homeless, describing a similar model, which can ‘create a bridge between separation and integration, opening up access to mainstream care for the majority of HP and also providing immediate transitional primary healthcare and social care services through interested GPs’.30 As some GPs explained it in our interviews, dedicated structures, which answer to the social needs for HP, could be the first contact in care for homeless. The homeless could secondarily be sent to ‘standard’ GPs when they had recovered sufficient social rights and personal capacity to follow an adequate itinerary of care. Wright et al recall that a specialised general practice for HP is ideal to engage them in care and guide them in the ‘appropriate use of primary care’; after this, the patient can be ‘encouraged to register with a mainstream practice’. But Wright et al69 remember that ‘this switch can be difficult not only for patients but also for doctors when there is a strong personal commitment’. It is necessary to identify GPs who could engage in the care of HP, offer them training about precariousness, and foster closer collaboration their practices and those of the dedicated system. These tailored structures could also become a source for crisis management or a support for GPs who need assistance in the care managing of HP.

Conclusion

GPs could effectively contribute to the improvement of the HPs health, if organisational and material conditions of their practices were adapted properly. It is necessary to develop a grouped and multidisciplinary offering, permitting an integrated medicopsychosocial approach. These results will enable the construction of a new model of primary care organisation to improve access to healthcare for HP.

Acknowledgments

Professor Giusiano Bernard helped to elaborate the research question, and to design the study. Professor Tanti-hardouin Nicolas gave useful advices to enhance our reflection concerning homelessness. Petit Juny, Welch Adam and Popescu Diana-Elena provided writing assistance (language editing).

Footnotes

Contributors: MJ designed the study, performed data collection on the three phases (all interviews, and questionnaires), performed the analyses, drafted the article and approved the final version; DG co-directed the third part of this study, contributed to the conception of the work and interpretation of data, revised the article and approved the final version; HB directed this whole work, gave advices for designing the study and analyses, revised the article and approved the final version; RS gave advices for designing the study, revised the article and approved the final version; AL gave advices for designing the study, supported the data analyses, revised the article and approved the final version; AD participated to the building of the research question, was a support to enhance the methodology of this study (at each methodological step), gave advices concerning the data analysis process, revised the article for editing the methods and discussion about mixed methods, and approved the final version. GG contributed to the conception of the work and interpretation of data, revised the article and approved the final version; SG was the tutor of this whole work, gave advices to get research scholarship, gave advices for designing the study and analyses, revised the article and approved the final version.

Funding: Phases 1 and 2 of this work were supported by AP-HM (Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille) and ARS PACA (regional health agency of region PACA): research scholarship allocated to the principal author (MJ) to perform a public health research master during year 2013–2017 (M-2013/2014-8).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine of Aix-Marseille University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.j9q7h.

References

- 1.Yaouancq F, Lebrère A, Marpsat M et al. L'hébergement des sans-domicile en 2012. Des modes d'hebergement differents selon les situations familiales. INSEE Prem 2013;1455:4. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless . On the way home? FEANTSA monitoring report on homelessness and homeless policies in Europe. Brussels: FEANTSA, 2012:92.

- 3.Fondation Abbé Pierre. L'état du mal-logement en France, 21éme rapport annuel. 2016:388. Disponible on: http://www.fondation-abbe-pierre.fr/21e-rapport-etat-mal-logement-2016

- 4.Gueguen F, Charrier L, Cirbeau C et al. Rapport annuel du 115. Année 2012 FNARS, 2012. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Experts Contributions Consensus Conference on Homelessness. European consensus conference on homelessness. Brussels; déc 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edgar B. The ETHOS definition and classification of homelessness and housing exclusion. Eur J Homelessness 2012;6:219–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Commission. Communication from the commission Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce DP, Limbos M. Identification of cognitive impairment and mental illness in elderly homeless men: before and after access to primary health care. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:1110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014;384:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright NM, Tompkins CN. How can health services effectively meet the health needs of homeless people? Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laporte A, Chauvin P. Samenta: rapport sur la santé mentale et les addictions chez les personnes sans logement personnel d'Ile-de-France. Rapport final Observatoire du SAMU social de Paris & Inserm, 2010. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordentoft M, Wandall-Holm N. 10 year follow up study of mortality among users of hostels for homeless people in Copenhagen. BMJ 2003;327:81 10.1136/bmj.327.7406.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewett N, Hiley A, Gray J. Morbidity trends in the population of a specialised homeless primary care service. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:200–2. 10.3399/bjgp11X561203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people's perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1011–17. 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang SW, Ueng JJM, Chiu S et al. Universal health insurance and health care access for homeless persons. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1454–61. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.182022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L et al. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:71–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Power R, French R, Connelly J et al. Health, health promotion, and homelessness. BMJ 1999;318:590–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushel MB. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA 2001;285:200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De la Rochère B. La santé des sans-domicile usagers des services d'aide. INSEE Prem 2003;893:4. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C et al. Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the Street Health survey. Open Med 2011;5:e94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marron-Delabre A, Rivollier E, Bois C. [Doctor-patient relationship in situations of economic precarity: the patient's point of view]. Santé Publique 2015;27:837–40. [French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farnarier C, Fano M, Magnani C et al. Trajectoire de soins des personnes sans abri á Marseille. Rapport de recherche final. ARS-PACA/APHM/UMI 3189. p136.

- 23.Little GF, Watson DP. The homeless in the emergency department: a patient profile. J Accid Emerg Med 1996;13:415–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley AJ, Harding G, Underwood MR et al. Homelessness: a problem for primary care? Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:473–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang SW, Burns T. Health interventions for people who are homeless. Lancet 2014;384:1541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kertesz SG, Holt CL, Steward JL et al. Comparing homeless persons’ care experiences in tailored versus nontailored primary care programs. Am J Public Health 2013;103(Suppl 2):S331–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crane M, Warnes AM. Primary health care services for single homeless people: defects and opportunities. Fam Pract 2001;18:272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lester H, Wright N, Heath I. Developments in the provision of primary health care for homeless people. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:91–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Léal F, Larpin C, Bauduceau A et al. La précarité sanitaire vue par les médecins. Humanit Enjeux Prat Débats 2011. [French] http://humanitaire.revues.org/1101 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben Hammou K. Le patient précaire au cabinet de médecine générale. Le point de vue des généralistes ayant une expérience de soins auprès des populations précaires [doctoral thesis N°2014ROUEM048]. Faculté de médecine de Rouen, 2014. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flye Sainte Marie C, Querrioux I et al. [Difficulties in the management of precarious patients and precarious migrants]. Santé Publique 2015;27:679–90. [French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood N, Wilkinson C, Kumar A. Do the homeless get a fair deal from general practitioners? J R Soc Health 1997;117:292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiffou H. Diagnostic auprès des médecins généralistes du centre-ville de Marseille sur la prise en charge des patients en situation de précarité [master thesis]. Nancy, Université Henri Poincaré, 2007. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guével MR, Pommier J. [Mixed methods research in public health: issues and illustration]. Santé Publique 2012;24:23–38. [French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridde V, Haddad S. [Pragmatism and realism for public health intervention evaluation]. Rev D’épidémiol Santé Publique 2013;61(Suppl 2):S95–106. [French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisdom J, Creswell JW. Mixed methods: integrating quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis while studying patient-centered medical home models. Report No.: 13-0028-EF Agency for Healthcare REsearch and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th edn Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2014:273. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Apostolidis T. Social representations and triangulation: an application in social psychology of health. Psicol Teor E Pesqui 2006;22:211–26. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson G, Macnaughton E, Goering P. What qualitative research can contribute to a randomized controlled trial of a complex community intervention. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;45(Pt B):377–84. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meschede T, Chaganti S. Home for now: a mixed-methods evaluation of a short-term housing support program for homeless families. Eval Program Plann 2015;52:85–95. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macnaughton EL, Goering PN, Nelson GB. Exploring the value of mixed methods within the At Home/Chez Soi housing first project: a strategy to evaluate the implementation of a complex population health intervention for people with mental illness who have been homeless. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santé Publique 2012;103(7 Suppl 1):eS57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanchet A, Gotman A. L'enquête et ses méthodes: l'entretien. Paris: Armand Colin, 2005:128. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siccama CJ, Penna S. Enhancing validity of a qualitative dissertation research study by using NVivo. Qual Res J 2008;8:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nombre d'activités exercées par les médecins par spécialité, secteur d'activité, tranche d’âge et sexe. Data from year 2015. Drees. http://www.data.drees.sante.gouv.fr/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=1164.

- 46.Sass C, Guéguen R, Moulin JJ et al. [Comparison of the individual deprivation index of the French Health Examination Centres and the administrative definition of deprivation]. Santé Publique 2006;18:513–22. [French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labbe E, Blanquet M, Gerbaud L et al. A new reliable index to measure individual deprivation: the EPICES score. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:604–9. 10.1093/eurpub/cku231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carde E. Les discriminations selon l'origine dans l'accès aux soins. Santé Publique 2007;19:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:907–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotobi L. Le malade dans sa difference: les professionnels et les patients migrants a l'hopital. Hommes Migr. juin 2000;Sante, le traitement de la difference(1225).

- 51.Huberman M, Miles MB. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd edn SAGE Publications, Inc, 1994:352. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baskerville NB, Hogg W, Lemelin J. Process evaluation of a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns improving preventive care. J Fam Pract 2001;50:W242–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Driscoll DL, Appiah-Yeboah A, Salib P et al. Merging qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research: how to and why not. Ecol Environ Anthropol Univ Ga 2007;18:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flick U. Triangulation revisited: strategy of validation or alternative? J Theory Soc Behav 1992;22:175–97. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukamurera J, Lacourse F, Couturier Y. Des avancées en analyse qualitative: pour une transparence et une systématisation des pratiques. Rech Qual 2006;26:110–38. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miron JM, Dragon JF. La recherche qualitative assistée par ordinateur pour les budgets minceurs, est-ce possible. Rech Qual 2007;27:152–75. [French]. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lejeune C. Manuel d'analyse qualitative analyser sans compter ni classer. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur, 2014. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers M. Contextualizing theories and practices of bricolage research. Qual Rep 2012;17:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mannoni C. Accompagnement à l’élaboration de réponses aux problèmes d'accès aux soins et de continuité des soins pour les personnes sans-abri à Marseille, rapport final. Observatoire social de Lyon, 2011. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zlotnick C, Zerger S, Wolfe PB. Health care for the homeless: what we have learned in the past 30 years and what's next. Am J Public Health 2013;103(Suppl 2):S199–205. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lester H, Bradley CP. Barriers to primary healthcare for the homeless: the general practitioner's perspective. Eur J Gen Pract 2001;7:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woodhead EL, Sperry JA, Bower EH et al. Attitude change following a homeless clinic experience. Fam Med 2009;41:83–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Brien R, Wyke S, Guthrie B et al. An ‘endless struggle’: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses’ experiences of managing multimorbidity in socio-economically deprived areas of Scotland. Chronic Illn 2011;7:45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Di Nino F, Imbs JL, Melenotte GH et al. Dépistage et traitement des hépatites C par le réseau des microstructures médicales chez les usagers de drogues en Alsace, France, 2006–2007. BEH 2009:400–4. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Nino F, Imbs JL, Melenotte GH et al. Progression de la couverture vaccinale vis-à-vis de l'hépatite B chez les usagers de substances psychoactives suivis par le réseau des microstructures médicales d'Alsace, 2009–2010. BEH 2014;(11):192–200. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ernst S, Mériaux I. Les internes de médecine générale face aux inégalités sociales de santé: faire partie du problème ou contribuer à la solution? Connaissances et représentations des internes Marseillais de médecine générale sir les inégalités sociales de santé, les dispositifs d'accès aux soins et les personnes bénéficiaires. Etude quantitative et qualitative [doctoral thesis N°2013AIXM6053], Marseille: Aix-Marseille Université, 2013. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sallé J. Vulnérabilités, accès aux soins et santé des migrants en séjour précaire: connaissances et représentations des internes en médecine générale d'Ile-de-France [doctoral thesis N°2010PA06G004], France: Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris). UFR de médecine Pierre et Marie Curie, 2010. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rode A. Le'non-recours’ aux soins des populations précaires. Constructions et réceptions des normes [doctoral thesis N°2010GRENH016]. Université Pierre Mendès-France-Grenoble II, 2010. [French] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wright NMJ, Tompkins CNE, Oldham NS et al. Homelessness and health: what can be done in general practice? J R Soc Med 2004;97:170–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013610supp1.pdf (741.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013610supp2.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)