Abstract

Objectives

To study the changes in prevalence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant smokers over time and legislative changes.

Design and setting

Retrospective nationwide cohort.

Participants

Our study consisted of 9627 randomly selected pregnancies from the Finnish Maternity Cohort (1987–2011), with demographic characteristics and pregnancy and perinatal data obtained from the Medical Birth Registry and early pregnancy serum samples analysed for cotinine levels. Women were categorised based on their self-reported smoking status and measured cotinine levels (with ≥4.73 ng/mL deemed high). Data were stratified to three time periods based on legislative changes in the Tobacco Act.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Prevalence of pregnant smokers and demographics, and perinatal and pregnancy outcomes of pregnant smokers over time.

Results

Overall, 71.6% of women were non-smokers, 16.2% were active cigarette smokers, 7.7% undisclosed smoking but had high cotinine levels and 4.5% were inactive cigarette smokers. The prevalence of active cigarette smokers decreased from mid-1990s onwards among women aged ≥30 years, probably due to the ban of cigarette smoking in most workplaces. We observed no changes in the prevalence of inactive smokers or women who undisclosed smoking by time or legislative changes.

Women who undisclosed smoking had similar characteristics and perinatal outcomes as inactive and active smokers. Compared with non-smokers, women who undisclosed smoking were more likely to be young, unmarried, have a socioeconomic status lower than white-collar worker and have a preterm birth.

Conclusions

Women who undisclosed smoking were very similar to pregnant cigarette smokers. We observed a reduction in the prevalence of active pregnant cigarette smokers after the ban of indoor smoking in workplaces and restaurants, mostly among women aged ≥30 years.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Pregnant smokers were identified using early pregnancy cotinine measurements with self-reports.

Our data spawn over three major changes in the Finnish Tobacco Act, allowing us to estimate the effect of stricter tobacco legislation on the prevalence of pregnant smokers.

We used only one-time cotinine measurement and were therefore not able to capture women who changed their smoking habits during pregnancy.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking has been acknowledged as a serious public health concern since the 1960s when the Surgeon General published the first report on smoking and health.1 Since then, tobacco acts have been passed in various countries in an effort to reduce health risks posed by cigarette smoking.1 Although the overall prevalence of cigarette smoking has declined,2–4 currently up to 16% of working-aged Finns smoke daily.4

Smoking has been causally linked to mortality and several common diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes.1 Smoking during pregnancy is known to be harmful to the fetal growth and development, including long-term health risks posed to the child,1 leading to an intergenerational cycle of poor health. Still, cigarette smoking remains prevalent among pregnant women, with a prevalence of 17% in Finland and 13% in the USA.3 5 Notably, the prevalence of cigarette smokers among pregnant women remains high in Finland for unknown reasons, whereas a declining prevalence has been observed in other Nordic countries.5

Previous studies have shown that up to 23% of pregnant women under-report smoking when their self-reported smoking status is compared with serum cotinine levels.6 However, there are little data showing if the prevalence of cigarette smoking, smoking non-disclosure or characteristics of women who undisclosed cigarette smoking during pregnancy has changed over time or due to changes in tobacco acts.

In this study with objectively measured tobacco exposure during pregnancy, we evaluated the effect of changes in the Finnish Tobacco Act on the prevalence and characteristics of active and non-active pregnant smokers and of women who undisclosed smoking during pregnancy.

Methods

Study population

Our retrospective cohort consisted of 9627 singleton pregnancies (1987–2011) with pregnancy and perinatal data obtained from the Finnish Medical Birth Registry (MBR) and serum samples obtained from the Finnish Maternity Cohort (FMC). The MBR, established in 1987, collects data on all pregnancies resulting in birth of live and stillborn infants with gestational age ≥22 weeks or with birth weight ≥500 g. The registry data are collected via a structured form filled by healthcare professionals by the time the infant is discharged from the delivery hospital or is 7 days old, whichever occurs first. Major changes to the structured form were implemented in 1990, 1996 and 2004. The FMC is a repository of left-over serum samples from infectious diseases screening used to screen women for hepatitis B, HIV and syphilis between 10 and 12 weeks' gestation. The samples are stored at −25°C in polypropylene cryo vials. The participation rate has been very high, more than 99%, since the establishment of the FMC in 1983. The FMC and MBR data were linked by using personal identity codes by personnel uninvolved in statistical analyses. Since 2002, the FMC contains an informed consent from the participants for the storage of the samples and their use for research. Research use of samples collected prior to 2002 is allowed under Finnish law. The study subjects were not contacted for this study.

Our final study population of 9627 singleton pregnancies (1987–2011) with serum samples obtained within a year of the index pregnancy was formed after we randomly selected 10 874 serum samples from the FMC and excluded 537 samples without data from the MBR (as pregnancies not resulting in a birth in Finland), 576 samples where the birth occurred more than a year prior or after the index pregnancy (as pregnancies without serum samples) and 134 multiple births. The final sample size was influenced by our financial and human resources.

Smoking status

In the MBR structured forms, women self-reported smoking during pregnancy as ‘non-smoking’, ‘ceased smoking during the first trimester’, ‘continued smoking after the first trimester’ or ‘not known’ since 1990. Prior to 1990, women self-reported smoking as ‘non-smoking’, ‘smoking <10 cigarettes per day’, ‘smoking >10 cigarettes per day’ or ‘unknown’. Based on these self-reports, we categorised women as non-smokers, women who ceased smoking during early pregnancy, active smokers and women with unknown smoking status during pregnancy.

We objectively measured smoking status by measuring serum cotinine levels from early pregnancy serum samples, obtained within a year of the index pregnancy (N=201; 2.1%) or during the index pregnancy (N=9425; 97.9%). Serum cotinine was measured using a commercially available quantitative immunoassay kit (STC Technologies, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA, currently: OraSure Technologies) by trained laboratory professionals. Serum cotinine concentrations ≥4.73 ng/mL were deemed high,7 and were used to classify women as smokers and non-smokers. This cut-off has been shown to have 97.5% sensitivity and 98.8% specificity to detect smokers among non-Hispanic white females.7 With this cut-off and our data of pregnant women, we detected a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 91.1%. We also studied a higher cut-off, where we deemed serum cotinine concentrations ≥10 ng/mL as high, but using this cut-off increased specificity only marginally to 92.4% and decreased sensitivity to 90.0%. Hence, we decided to use the lower and more conservative cut-off in order to retain sensitivity.

Based on the self-reported smoking status and objectively measured serum cotinine levels, women were categorised as:

Non-smokers (N=6892): women with self-report of non-smoking who had low cotinine concentrations (<4.73 ng/mL).

Women who undisclosed smoking (N=745): women with self-report of non-smoking who had high cotinine concentrations or women with unknown smoking status during pregnancy who had high cotinine concentrations (≥4.73 ng/mL).

Inactive cigarette smokers (N=431): women with self-report of active smoking who had low cotinine concentrations (<4.73 ng/mL), women who ceased smoking during pregnancy who had low cotinine concentrations (<4.73 ng/mL) or women with unknown smoking status during pregnancy and who had low cotinine concentrations (<4.73 ng/mL).

Active cigarette smokers (N=1559): women with self-report of active smoking who had high cotinine concentrations (≥4.73 ng/mL) or women who ceased smoking who had high cotinine concentrations (≥4.73 ng/mL).

Legislative changes in the Finnish Tobacco Act

We identified three major changes during the study in the Finnish Tobacco Act, passed in 1976 in an effort to reduce cigarette smoking among Finns.8 First, the indirect advertisement of tobacco products and cigarette smoking indoors in workplaces (excluding restaurants), governmental buildings and in public transportation was banned and the legal age to buy tobacco products was raised from 16 to 18 years in 1994. Second, in 2004, the indoor smoking ban was extended to restaurants. Third, in 2010, the public display of cigarette products at shops was banned.

Demographic and outcome data

Data on maternal characteristics during pregnancy, including age, marital status, prepregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight/height2 in kg/m2), socioeconomic status based on maternal occupation before or during pregnancy (upper white-collar worker, lower white-collar worker, blue-collar worker and others including, eg, students and housewives) pregnancy history and number of visits to the maternity care clinics as well as perinatal data including child's gestational age at birth, whether child was born dead or alive and mode of birth were obtained from the MBR.

Statistical analyses

We multiple imputed all data to account for differences in the data collection due to differences in the structured forms of the MBR. Maternal prepregnancy weight and height were not asked prior to 2004 in the structured forms and hence, they were missing by design for most women in our cohort. Other missing data were rare. All exposure, covariate and outcome data were included in multiple imputation process. We performed five multiple imputations. All statistical analyses were run with the multiple imputed data as well as with the original data. As overall the results were similar, only the results from the multiple imputed data are presented. However, as data on maternal body mass index prior to 2004 were based only on imputed data, we used only data from 2004 onwards when evaluating the differences in body mass index among smokers and non-smokers.

Contingency tables were used when evaluating the prevalence of non-smokers and pregnant cigarette smokers by time with visual interpretation of trends. We stratified the data to women aged <30 and ≥30 years to study if the prevalence by time is different among young and older women.

We used contingency tables with χ2 tests to evaluate the difference in prevalence of categorical variables by objectively measured smoking status. To account for the possible changes of legislative changes in the Tobacco Act in the maternal and perinatal characteristics of pregnant cigarette smokers, we modelled the analyses as the effect of objectively measured smoking status (with non-smokers as the reference group), the effect of time (stratified to three time points according to changes in the Tobacco Act: 1987–1993, 1994–2003 and 2004–2011) and the interaction between objectively measured smoking status and time. We used logistic regression to estimate ORs with 95% CIs of maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes at different times.

We also performed a regression analysis with splines using Joinpoint Regression Program V.4.3.1.0.9 The number of women in each group by year (as a log-transformed variable) was used to model the regression with 0–5 splines and the model with the best fit was selected as a final representation of the trend in each group. The analysis was separately repeated for women aged <30 and ≥30 years. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded all women who did not have serum cotinine measured in the index pregnancy. All statistical analyses were performed by IBM SPSS Statistics, V.22 (IBM Statistics, New York, USA).

Results

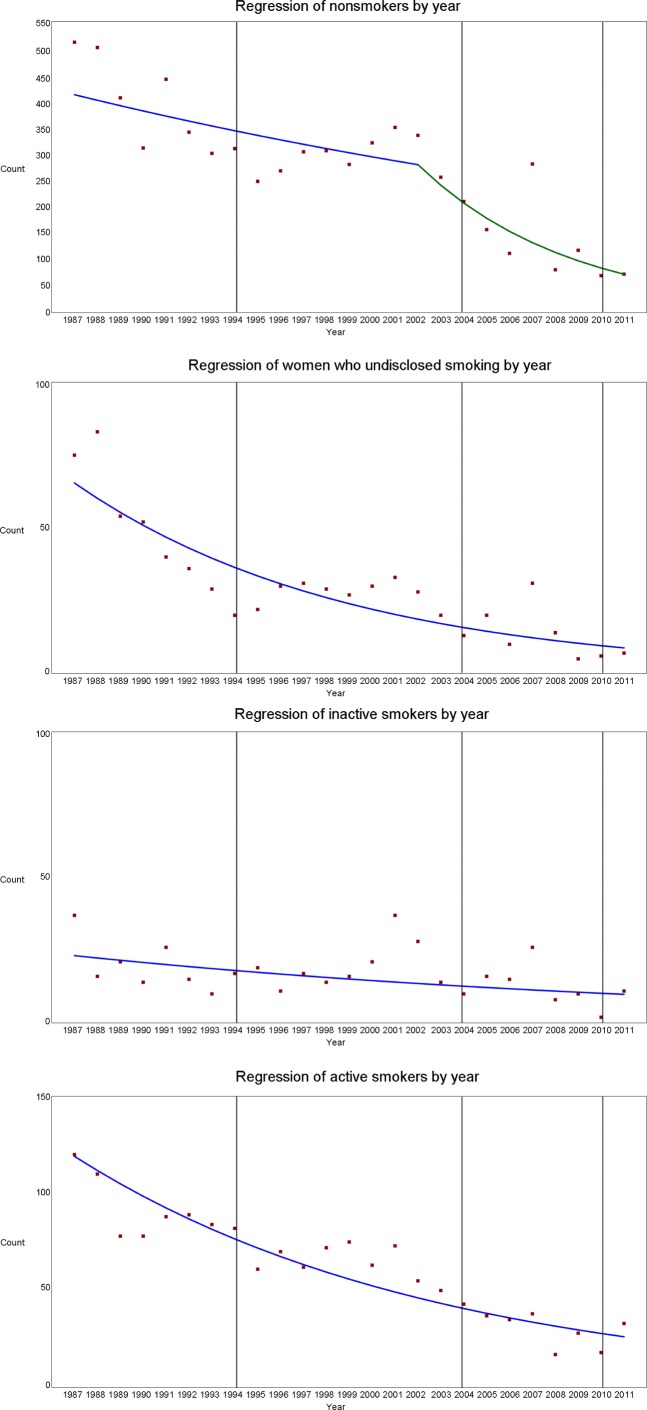

The overall prevalence of non-smokers was 71.6%. The prevalence of non-smokers ranged from 58.9% in 2011 to 76.1% in 2004. The number of non-smokers declined steadily until 2002 based on our regression data, with annual per cent change of −2.5% (95% CI −5.5% to 0.5%). After 2002, the decrease in the number of non-smokers was steeper, with an annual per cent change of −13.9% (95% CI −19.5% to −7.9%) (figure 1). The number of non-smokers <30 years did not show any meaningful trends over time, but the number of non-smokers aged ≥30 years followed that of the whole non-smoker group.

Figure 1.

Regression with splines of number of women in the non-smoker, inactive and active cigarette smoking and women who undisclosed smoking during pregnancy groups by time and legislative changes.

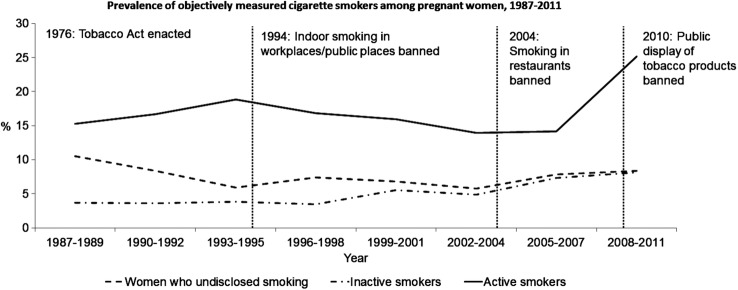

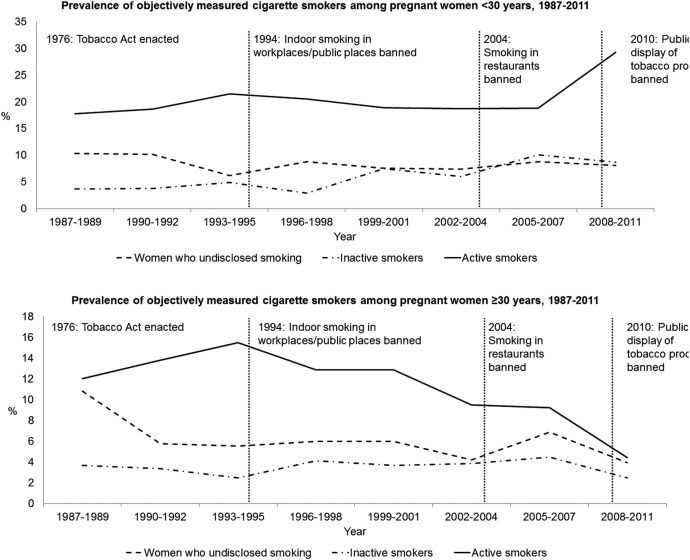

Altogether, 16.2% of pregnant women were active cigarette smokers. The prevalence of active cigarette smokers ranged from 10.1% in 2007 to 26.6% in 2011 (figure 2). This prevalence was slightly reduced from mid-1990s to 2007, with an increase in the prevalence in 2008–2011 (figure 2). This increase was more prominent among women aged <30 years, whereas the prevalence of active smokers has decreased among women aged ≥30 years since mid-1990s (figure 3). In the regression model, the number of active smokers decreased steadily over time with an annual per cent change of −6.1% (95% CI −7.3% to −4.9%) (figure 1) and a similar trend was observed among women <30 years. However, among women aged ≥30 years, there was a decreasing trend with an annual per cent change of −3.8% (95% CI −7.2% to −0.3%) until 2005 and an annual per cent change of −38.0% (95% CI −48.7% to −25.2%) since 2005.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of inactive and active cigarette smoking and women who undisclosed smoking during pregnancy by time and legislative changes.

Figure 3.

The prevalence of inactive and active cigarette smoking and women who undisclosed smoking during pregnancy by time and legislative changes, stratified by maternal age.

The prevalence of inactive smokers was 4.5% and the prevalence ranged from 2.1% in 2010 to 8.9% in 2011 (figure 2). There was a slight increase in the prevalence of inactive pregnant smokers from late 1990s to 2007 (figures 2 and 3), although the regression model showed a decrease in the number of inactive smokers over time with an annual per cent change of −3.5% (95% CI −6.4% to −0.5%) (figure 1).

The prevalence of women who undisclosed smoking was 7.7%. The prevalence ranged from 3.1% in 2009 to 11.7% in 1988 and 2008 (figure 2). There was decrease in the prevalence of women who undisclosed smoking in the crude model and in the regression model, with an annual per cent change of −8.0% (95% CI −10.0% to −6.0%) (figures 1 and 2). The decrease was more prominent among women aged ≥30 years (figure 3).

Maternal characteristics

Compared with non-smokers in 1987–1993, active smokers were younger, less often married, had more often socioeconomic status lower than white-collar worker and were more often nulliparous (table 1). They also had fewer visits to the maternity care clinics (table 1). The characteristics of active smokers did not substantially change with the stricter Tobacco Acts enacted in 1994 and 2004 (table 1). Women who undisclosed smoking and non-active smokers had maternal characteristic comparable to active smokers at all time periods (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and pregnancy history of pregnant women by objectively measured smoking status

| Non-smokers (N=6892) (reference category) | Women who undisclosed smoking (N=745) |

Inactive cigarette smokers (N=431) |

Active cigarette smokers (N=1559) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) |

| Age <30 years | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 56.1 | 60.7 | 1.21 (0.97 to 1.51) | 59.7 | 1.16 (0.82 to 1.64) | 66.3 | 1.54 (1.29 to 1.84) |

| 1994–2003 | 47.7 | 61.9 | 1.78 (1.38 to 2.30) | 62.9 | 1.86 (1.38 to 2.51) | 62.9 | 1.86 (1.56 to 2.21) |

| 2004–2011 | 45.0 | 62.3 | 2.02 (1.34 to 3.04) | 71.4 | 3.05 (1.94 to 4.81) | 75.9 | 3.85 (2.81 to 5.27) |

| Unmarried | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 19.0 | 40.4 | 2.88 (2.66 to 3.66) | 30.2 | 1.84 (1.23 to 2.74) | 46.8 | 3.77 (3.13 to 4.54) |

| 1994–2003 | 26.5 | 48.5 | 2.62 (2.00 to 3.45) | 37.6 | 1.67 (1.22 to 2.28) | 51.9 | 2.99 (2.51 to 3.56) |

| 2004–2011 | 29.8 | 41.5 | 1.65 (1.09 to 2.48) | 43.9 | 1.83 (1.19 to 2.80) | 57.8 | 3.22 (2.37 to 4.38) |

| <15 visits to maternity care | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 42.2 | 45.3 | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.41) | 46.0 | 1.16 (0.81 to 1.67) | 46.8 | 1.21 (1.02 to 1.44) |

| 1994–2003 | 35.9 | 41.1 | 1.25 (0.96 to 1.61) | 34.0 | 0.92 (0.67 to 1.26) | 35.3 | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.40) |

| 2004–2011 | 37.9 | 31.1 | 0.75 (0.49 to 1.15) | 30.6 | 0.71 (0.45 to 1.12) | 32.9 | 0.80 (0.60 to 1.08) |

| Prepregnancy body mass index not normal* | |||||||

| 2004–2011 | 41.1 | 40.6 | 0.99 (0.65 to 1.51) | 39.8 | 0.96 (0.63 to 1.48) | 41.8 | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.45) |

| Socioeconomic status lower than white-collar worker | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 35.7 | 43.4 | 1.37 (0.88 to 2.13) | 39.6 | 1.16 (0.75 to 1.80) | 46.5 | 1.56 (1.14 to 2.13) |

| 1994–2003 | 35.8 | 55.6 | 2.26 (1.74 to 2.94) | 46.9 | 1.59 (1.17 to 2.16) | 62.3 | 2.96 (2.46 to 3.55) |

| 2004–2011 | 41.7 | 57.5 | 1.89 (1.25 to 2.87) | 57.1 | 1.83 (1.18 to 2.84) | 72.7 | 3.75 (2.71 to 5.18) |

| Nulliparous | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 44.6 | 52.8 | 1.40 (1.12 to 1.75) | 56.1 | 1.60 (0.90 to 2.87) | 49.3 | 1.21 (1.02 to 1.44) |

| 1994–2003 | 45.8 | 52.6 | 1.30 (1.02 to 1.67) | 54.1 | 1.39 (1.03 to 1.87) | 50.8 | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.45) |

| 2004–2011 | 43.6 | 46.2 | 1.23 (0.75 to 2.03) | 55.1 | 1.26 (0.78 to 2.04) | 59.4 | 1.51 (1.09 to 2.10) |

*Includes subjects with body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 and subjects with body mass index ≥25 kg/m2. These data were not available prior to 2004.

Perinatal characteristics

From 1987 to 2003, women who undisclosed smoking had higher odds of preterm birth than non-smokers (table 2). In 1987–1993, inactive cigarette smokers also had higher odds of preterm birth than non-smokers (table 2). Active cigarette smokers also had higher odds of preterm birth from 1987 to 2003 and additionally, in 1994–2003, they had higher odds of child being hospitalised during early neonatal period compared with non-smokers (table 2).

Table 2.

Perinatal outcomes of women by objectively measured smoking status, time and legislative changes to the Tobacco Act

| Outcome | Non-smokers (N=6892) (reference category) | Women who undisclosed smoking (N=745) |

Inactive cigarette smokers (N=431) |

Active cigarette smokers (N=1559) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks' gestation | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 4.8 | 7.4 | 1.59 (1.04 to 2.44) | 10.4 | 2.30 (1.27 to 4.17) | 7.6 | 1.64 (1.17 to 2.30) |

| 1994–2003 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 1.59 (1.06 to 2.39) | 9.2 | 1.27 (0.76 to 2.11) | 10.7 | 1.51 (1.14 to 2.00) |

| 2004–2011 | 6.1 | 9.4 | 1.61 (0.80 to 3.23) | 9.4 | 1.64 (0.79 to 3.40) | 7.6 | 1.28 (0.75 to 2.17) |

| Perinatal deaths | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.86 (0.11 to 6.94) | 2.9 | 5.26 (0.93 to 29.65) | 0.9 | 2.57 (0.93 to 7.11) |

| 1994–2003 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.73 (0.51 to 5.89) | 1.8 | 2.72 (0.79 to 9.33) | 0.6 | 0.94 (0.32 to 2.76) |

| 2004–2011 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.38 (0.31 to 6.10) | 1.0 | 0.74 (0.10 to 5.64) | 1.6 | 1.17 (0.38 to 3.55) |

| Child hospitalised during early neonatal period | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 1.44 (0.90 to 2.29) | 8.7 | 1.97 (0.82 to 4.75) | 5.3 | 1.19 (0.80 to 1.75) |

| 1994–2003 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 1.18 (0.71 to 1.98) | 7.3 | 1.33 (0.75 to 2.37) | 9.1 | 1.68 (1.24 to 2.29) |

| 2004–2011 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 2.06 (0.98 to 4.33) | 4.5 | 1.03 (0.36 to 2.91) | 6.5 | 1.52 (0.85 to 2.72) |

| Caesarean delivery | |||||||

| 1987–1993 | 15.6 | 14.2 | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.22) | 14.4 | 0.90 (0.53 to 1.53) | 15.0 | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.21) |

| 1994–2003 | 22.0 | 19.9 | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.20) | 23.8 | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.56) | 20.8 | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.15) |

| 2004–2011 | 17.1 | 10.4 | 0.56 (0.30 to 1.07) | 16.3 | 0.95 (0.54 to 1.66) | 16.1 | 0.93 (0.64 to 1.35) |

The ORs with 95% CIs are obtained from binomial logistic regression, where we modelled the effect of objectively smoking status, time and the interaction between objectively measured smoking status and time.

Sensitivity analysis

All results were similar after excluding women whose serum cotinine measurements were performed outside the index pregnancy (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study of randomly selected pregnancies from 1987 to 2011 with objectively measured smoking status, we observed a reduction in active cigarette smoking. This reduction was mostly observed among pregnant women aged ≥30 years from 2005 onwards. The reduction in the prevalence of active pregnant cigarette smokers may be due to two major legislative changes in the Tobacco Act: the ban of indoor smoking in workplaces other than restaurants in 1994 and the extension of the ban to restaurants in 2004. However, we did not observe any meaningful changes in the prevalence of inactive pregnant cigarette smokers or in the prevalence of women who undisclosed smoking by time. Additionally, we found that pregnant women who undisclosed smoking had very similar characteristics and pregnancy outcomes as pregnant cigarette smokers. Time or legislative changes had very little effect on the characteristics or perinatal outcomes of pregnant smokers.

Public health acts have been successful in reducing smoking among men, but only recently the prevalence of cigarette smoking has started to decrease among women.2 However, the prevalence of cigarette smoking among pregnant women has been around 16% since the 1980s in Finland,4 5 10 and around 13% in the USA since 2000.3 By objectively measuring smoking status, we found a prevalence of 16% of active cigarette smokers among pregnant Finnish women, but additionally nearly 8% of pregnant women undisclosed smoking. Also, nearly 5% of women self-reported smoking but had low cotinine levels. This group may represent pregnant women who had managed to quit smoking during early pregnancy, but who still honestly reported that they had smoked cigarettes. Alternatively, these inactive smokers may be pregnant women who smoke only occasionally which may have resulted in low cotinine levels if they had not smoked the days prior to serum sampling for the FMC. Interestingly, these women had demographic characteristics and perinatal outcomes more similar to active cigarette smokers than non-smokers. This suggests that at least a portion of these women actually did smoke cigarettes during pregnancy, although our early pregnancy cotinine measurement did not capture it.

Our data clearly indicate that stricter Tobacco Acts have been successful in reducing active cigarette smoking among pregnant women aged ≥30 years, but in younger women the public health measures have been less successful. It has been shown that older and married women are more lenient towards restriction of availability of tobacco products and restrictions to smoking in public places.8 Younger women also seem to perceive smoking and alcohol use to be less harmful in pregnancy than older women,11 which may partly explain our results.

Our data show that the prevalence of women who undisclosed smoking has not changed with time or legislative acts. We hypothesised that women who undisclosed smoking would be older and more educated women, based on the assumption that these women would know about the harms of cigarette smoking on the fetal development and would therefore hide their harmful habits from their healthcare professional. However, the opposite was observed in this study, as women who undisclosed smoking were more often <30 years old, nulliparous, not married and had a socioeconomic status lower than white-collar worker. The characteristics of women who undisclosed smoking were very similar to pregnant women who actively smoked cigarettes.

In one previous study from the USA, 13% of pregnant women were active cigarette smokers and of them, nearly 23% disclosed smoking.6 Non-disclosure of cigarette smoking was higher among pregnant than non-pregnant women.6 In that study, non-disclosure was associated with younger age and Mexican-American and non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity.6 Our study population consisted mostly of white women with European background, and thus we observed no differences by race/ethnicity among women who did and did not disclose smoking. Similar to the study by Dietz et al,6 women who disclosed smoking in our study were younger than non-smoking mothers.

As expected, women who smoked and undisclosed smoking had higher odds of preterm birth. The odds of preterm birth among women who undisclosed smoking were very similar to active cigarette smokers, and most likely represent the direct harmful effects maternal cigarette smoke exposure has on fetal development.1

Our study was based on a randomly selected pregnant cohort with serum cotinine concentrations measured in early pregnancy. We were able to obtain detailed pregnancy and perinatal data on these women from the MBR. Our study population adequately represented different time points, including time points when legislative changes were enacted in the Tobacco Act. As a limitation, a small proportion of the samples used in our study were taken outside of the index pregnancy. However, our sensitivity analyses excluding these women were very similar to the main analyses. We also cannot exclude that some women, who self-reported to be non-smokers but who had high cotinine concentration, are true non-smokers who were exposed to passive smoking. However, we believe the proportion of such women to be small. Recent studies from the USA and the UK have shown that cotinine concentrations have decreased among non-smokers from the 1980s onwards, and those with passive smoking have a geometric mean of cotinine <2 ng/mL.12 13 This is true even when the partner of a non-smoker smoked more than 30 cigarettes per day.12

Our study has several public health implications. First, objectively measured smoking is still very prevalent among pregnant women. Smoking is causally associated with preterm birth and fetal growth restriction,1 and maternal smoking is also associated with long-term diseases in the children, such as asthma.14 However, public health efforts to reduce prevalence of smoking among pregnant women have mostly been successful among women aged ≥30 years. Substantial efforts are still needed to reduce the prevalence of cigarette smokers among younger women, preferentially even before pregnancy. Second, women who disclosed smoking should be actively sought in the maternity care as these women are at increased risk for preterm birth, for instance.

In conclusion, objectively measured cigarette smoking is prevalent among pregnant women and legislative changes have not had an effect on the prevalence of pregnant cigarette smokers among younger women. Women who undisclosed cigarette smoking are very similar to active cigarette smokers and have an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as preterm birth. Targeted public health efforts are needed to reduce the prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank Dr Anna-Maria Lähesmaa-Korpinen for her help and expertise in the regression analyses with splines.

Footnotes

Contributors: TM, HMS and AB designed and conceptualised the study. TM conducted the statistical analyses. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results. TM drafted the manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. TM is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Institute for Health and Welfare and the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. The Lancet 2015;385:966–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy--pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jääskeläinen M, Virtanen S. Tobacco statistics 2015. Helsinki, Finland: Official Statistics of Finland, National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heino A, Gissler M. Perinatal statistics in the Nordic countries 2014. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ et al. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:355–9. 10.1093/aje/kwq381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS et al. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:236–48. 10.1093/aje/kwn301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heloma A, Ollila H, Danielsson P et al. Kohti savutonta Suomea. Tupakoinnin ja tupakkapolitiikan muutokset. Tampere, Finland: Juvenes Print, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ et al. Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vuori E, Gissler M. Perinatal statistics: Parturients, deliveries and newborns 2013. Statistical report 23/2014 Helsinki, Finland: Official Statistics of Finland, National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen I, McCrea RL, Lupattelli A et al. Women's perception of risks of adverse fetal pregnancy outcomes: a large-scale multinational survey. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007390 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis MJ, Feyerabend C, Bryant A et al. Passive smoking in the home: plasma cotinine concentrations in non-smokers with smoking partners. Tob Control 2001;10:368–74. 10.1136/tc.10.4.368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirkle JL, Bernert JT, Caudill SP et al. Trends in the exposure of nonsmokers in the U.S. population to secondhand smoke: 1988–2002. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:853–8. 10.1289/ehp.8850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Dekker HT, Sonnenschein-van der Voort AM, de Jongste JC et al. Tobacco smoke exposure, airway resistance and asthma in school-age children: The Generation R study. Chest 2015; 148:607–17. 10.1378/chest.14-1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]