Abstract

Objectives

Fertility services in the UK are offered by over 200 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA)-registered NHS and private clinics. While in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) form part of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, many further interventions are offered. We aimed to record claims of benefit for interventions offered by fertility centres via information on the centres' websites and record what evidence was cited for these claims.

Methods

We obtained from HFEA a list of all UK centres providing fertility treatments and examined their websites. We listed fertility interventions offered in addition to standard IVF and ICSI and recorded statements about interventions that claimed or implied improvements in fertility in healthy women. We recorded which claims were quantified, and the evidence cited in support of the claims. Two reviewers extracted data from websites. We accessed websites from 21 December 2015 to 31 March 2016.

Results

We found 233 websites for HFEA-registered fertility treatment centres, of which 152 (65%) were excluded as duplicates or satellite centres, 2 were andrology clinics and 5 were unavailable or under construction websites. In total, 74 fertility centre websites, incorporating 1401 web pages, were examined for claims. We found 276 claims of benefit relating to 41 different fertility interventions made by 60 of the 74 centres (median 3 per website; range 0 to 10). Quantification was given for 79 (29%) of the claims. 16 published references were cited 21 times on 13 of the 74 websites.

Conclusions

Many fertility centres in the UK offer a range of treatments in addition to standard IVF procedures, and for many of these interventions claims of benefit are made. In most cases, the claims are not quantified and evidence is not cited to support the claims. There is a need for more information on interventions to be made available by fertility centres, to support well-informed treatment decisions.

Keywords: fertility, evidence-based medicine, patient information

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We accessed all Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority-registered fertility centre websites available in the UK that provide in vitro fertilisation and treatment information.

Two reviewers accessed the websites, assessed all of the extracted claims and resolved issues by discussion.

Different reviewers may disagree in categorising some statements as claims, but it is unlikely that the pattern of findings would change substantially.

Web pages are subject to change over time, and a different set of reviewers might locate further intervention claims that we missed.

Background

Approximately one in seven UK couples have problems conceiving,1 and increasing age is one factor that contributes to this. Approximately 98% of women, aged between 19 and 26 years, and having regular intercourse will conceive naturally within 2 years. However, this figure drops to 90% for women aged between 35 and 39 years.2 Other factors that can affect fertility include ovulatory, tubal, uterine or peritoneal disorders as well as male-related factors. However, in ∼25% of couples, there is no identified cause of the infertility.1

Current UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines advocate that women with unexplained infertility, who have not conceived after 2 years of regular sexual intercourse, be offered NHS treatment. This may be through medical, surgical or assisted conception techniques. For women under 40 years of age, the latter includes three full cycles of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).3

In general, fertility treatments include an array of interventions that seek to aid conception, or treat infertility, or subfertility, with the specific aim of increasing the live birth rate or the pregnancy rate (sometimes called ‘clinical pregnancy rate’) as well as conception or survival of cultured embryos or blastocysts. Treatments often involve ovulation stimulation and monitoring, IVF itself (sometimes via ICSI) and replacement of resulting embryos or blastocysts into the uterus.

In addition to these standard treatments, a range of additional investigations and treatments may be offered at UK fertility treatment centres. All centres, whether they provide private, NHS or both types of services, are registered with the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), the independent regulator that oversees fertility treatment and research in the UK.4 However, despite this regulation it has been suggested that some of these interventions—offered beyond routine IVF—may not best serve patients, as they are not based on evidence of effectiveness, are costly and some clinics might be using IVF techniques that have not been stringently tested.5 Furthermore, the HFEA recommends that some treatments, such as reproductive immunology, are only used in the context of clinical trials.6

Given the concerns over the evidence base underpinning fertility treatments as well as the implications for couples undergoing these treatments, and the resources needed to fund them, we set out to systematically identify and document claims made by UK fertility centres on the effectiveness of treatments offered on their websites as the first information source for individuals. We went on to identify the evidence that the centres use to support their claims. Finally, using this information, we have conducted a follow-up study examining the credibility of the claim statements when compared with the published evidence of effectiveness.7

Methods

Identification of fertility claims

We obtained a list of all UK centres providing fertility treatments from the HFEA website.4 No centres were excluded. Where it was clear that a primary fertility centre had satellite centres offering treatments, we restricted our searching for claims to their main website. We examined the websites for each of these centres and for each intervention additional to IVF that was offered. We extracted statements that suggested or claimed improvements in fertility in healthy women. These included statements relating to increased conception rate, increased rate of ‘clinical pregnancy’ or relating to increased live birth rate.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for claims

We defined a claim as a statement that implicitly or explicitly asserted that an intervention provides enhanced effectiveness in relation to either increased conception rate, implantation rate, pregnancy rate or live birth rate. A list was made of all claims identified on the first website. In the websites accessed subsequently, these claims were all searched for, and additional claims identified were added to the list. In this way, the list of claims increased as the search continued through the list of fertility centres.

We excluded claims of effectiveness for:

IVF itself and its associated standard treatments.

Freezing of sperm or eggs.

Donation of sperm or eggs.

Nutrition, acupuncture or hypnotherapy.

Interventions in women with pre-existing disease such as diabetes or diagnosed conditions such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, or neurological conditions such as spinal cord injury.

Genetic testing of inherited disorders.

Interventions for women experiencing recurrent miscarriage.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (EAS and CH) independently listed interventions offered and extracted claims for the interventions. We accessed websites from 21 December 2015 to 31 March 2016 and accessed each website on one date only. When a website cited external evidence and provided a link to this, we recorded this link. We extracted a copy of the claims, and a list of the web pages viewed into a single Google data sheet. We recorded methodological issues and important contextual information relating to claims into the data sheet and analysed some of the emerging themes.

We counted the number of web pages accessed, the total number of claims per site, the presence or absence of quantification of the benefits for a given claim and the number of external references cited to justify claims. Clarification of the presence of a claim was achieved through discussion between the reviewers (EAS and CH). For each intervention, we then collated all of the claims and counted the number of fertility centres making a claim of benefit. We counted the number of websites giving a quantification of effect for a claim they made, how many websites cited an external reference for their claim and how many references were cited. Using the citations given on the websites, we attempted to identify and locate the published references cited by the fertility centres.

Results

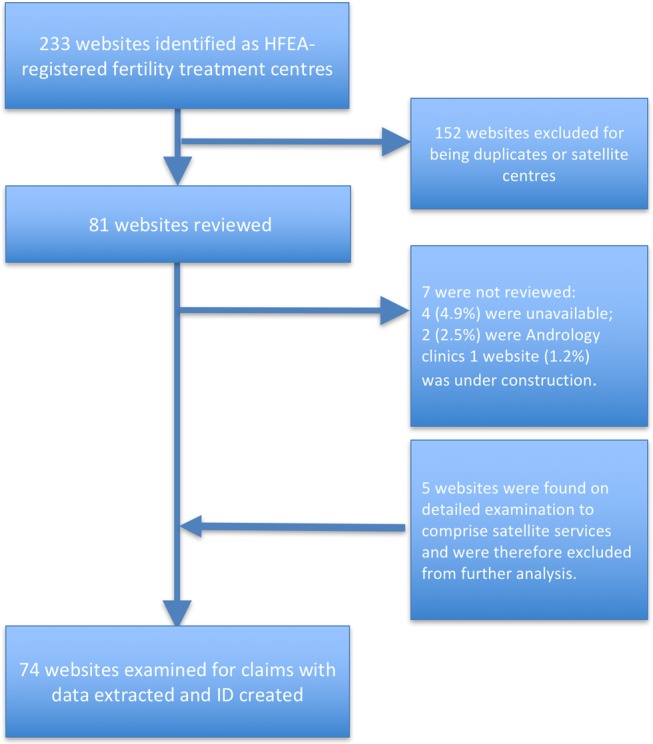

We identified 233 websites for HFEA-registered fertility treatment centres (websites searched December 2016), of which 152 (65%) were duplicates or satellite centres (information on these sites referred directly to one of the cohort of included websites). Of the 81 sites we reviewed, 4 (4.9%) were unavailable; 2 (2.5%) were andrology clinics and 1 website (1.2%) was under construction. Therefore, we included a total cohort of 74 (30%) separate websites of centres providing IVF services in the UK (see figure 1 and Supplementary table S1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of websites included in the analysis.

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table1.pdf (74.5KB, pdf)

Across these 74 sites, we searched 1401 web pages (median 16 per website; range 1–60) that related to treatment interventions meeting our inclusion criteria. We found 276 claims of benefit relating to fertility interventions made by 60 of the 74 centres (median 3 per website; range 0–10).

Examples of claim statements are shown in Supplementary table S2. Some of the claims were moderately direct, stating that the intervention increased the likelihood, optimised or increased the chance of conception or pregnancy. For example: “A pre-treatment scan gives the clinician the information they need to decide on the most appropriate treatment pathway for you. This allows the team to optimise your chances of achieving a pregnancy.” “Special tests may identify couples who are at risk of these problems. Treatment which stimulates the proper immune response (immunomodulation) in the mother may then improve the chances of a successful pregnancy.” Rarely, a claim stated that there was a benefit relating to live birth, for example: “Intralipid infusion therapy can help to stabilise your immune system and increase your chances of having a baby…. It is safe, non-invasive and may help to increase your chance of success.” Many of the claims were more indirect, suggesting a generalised benefit or improvement, for example: “Hyaluranon may also help to isolate mature sperm for use in ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) cycles helping to increase fertilisation rates.”

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table2.pdf (99.2KB, pdf)

The interventions additional to standard IVF offered on the websites are shown in Supplementary table S3. Quantification was given for 79 (29%) of the 276 claims. As an example, “chance of an embryo transferred to the womb making a baby was found to be increased by more than 50%.” In conjunction with the 276 claims, a total of 16 unique references were cited 21 times on 13 of the 74 websites. Supplementary table S4 shows the citations found on the websites and the corresponding references identified, by intervention offered, and shows the category for the highest level of evidence cited. References supported six interventions: IMSI (four unique publications); endometrial scratching (six unique publications cited in seven instances by four websites); Embryoglue (three unique references cited in eight instances by six websites); assisted hatching (one reference cited once on one website); vitrification of human eggs and embryos/EVES technique (one reference cited once on one website) and Embryoscope (one reference cited once on one website).

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table3.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table4.pdf (58.6KB, pdf)

Of the 16 cited references, four were systematic reviews.8 9 10 11 One was a meta-analysis,12 and two were randomised trials.13 14 Four were reports of prospective observational studies,15–18 and one was a report of a non-randomised parallel group intervention study.20 Two were reports of retrospective cohort studies,20 21 and two were conference abstracts, of which we were only able to locate one.22 Of the 74 websites, 61 (82%) provided no references. On the 13 websites that did, the number of references cited ranged from one (five sites) to nine references (one site: http://cheshirewomenshealth-fertility.co.uk/).

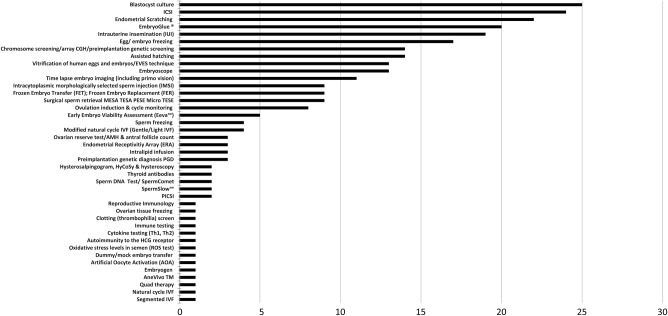

The 276 claims made related to 41 different interventions (figure 2): 8 of these were tests (shown in the table on a blue background), 6 were interventions considered part of NICE recommendations (shown on a yellow background), 1 was miscellaneous (natural cycle IVF, shown on a purple background) and 26 interventions or techniques were classified as additional to standard IVF treatments. Figure 2 shows that the five most commonly made claims were for blastocyst culture, ICSI, endometrial scratching, Embryoglue and IUI, accounting for 110 (39%) of the overall claims.

Figure 2.

Number of claim statements found on 74 fertility treatment websites, by intervention offered (total claims=276).

The eight tests for which claims were made included an ovarian reserve test/AMH and antral follicle count, thyroid antibodies, hysterosalpingogram, semen analysis and chromosome tests. For all these tests except immunology testing, NICE gives guidance,2 which was not referred to by any of the websites.

Six interventions for which claims were made are also referred to in current NICE recommendations23 and not referred to by the website in relation to claims: intrauterine insemination (IUI) (NICE recommendation 1.2.1.2); intracytoplasmic injection (ICSI) (NICE recommendation 1.11.1.2), cycle monitoring, ovulation induction and cycle monitoring (NICE recommendation 1.5.5.3, 1.5.4.2, 1.12.3.4 and 1.12.4) and egg freezing and sperm freezing (NICE recommendation 1.16.1 Cryopreservation of semen, oocytes and embryos). NICE guidance on cryopreservation relates to patients preparing to undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy when it is likely to affect their fertility (NICE recommendation 1.16.1.1) and is therefore in most cases not relevant to cryopreservation in patients without cancer seeking help with fertility.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Our findings demonstrate that while many claims were made on the benefits of fertility treatments, there was a lack of supporting evidence cited, with the majority of the websites providing no sources for claims made. From 74 websites and reviewing 1401 web pages from UK-based centres providing IVF treatments, we found a substantial number of claims of effectiveness for interventions additional to standard IVF treatment. Despite 276 claims made across these 74 websites, we identified only 13 websites where any references were included, which referred to just 16 unique published references. Of these 16 references cited, only 5 were high-level systematic review evidence; the remaining 12 were either small prospective or retrospective studies, including two conference abstract reports which include only limited information.

Strengths and weaknesses

We attempted to execute replicable methods, but there are some limitations worth noting. While our list of websites was provided by the UK regulator, web pages do change, and a different set of reviewers might locate further intervention claims that we missed, not least because on some sites it is not straightforward to locate all treatments offered. Different reviewers may disagree in categorising some statements as claims, and it is possible that a repeat of our analysis would record a different number of claims, but it is unlikely that the pattern of findings would change substantially. In this study, we examined only the evidence cited by these websites, and we did not examine all available evidence on the safety and effectiveness of the interventions for which claims were made. We have therefore followed this work with further research to examine the published evidence relating to fertility interventions identified in this study as being currently offered by regulated clinics and to investigate whether the claims of benefit can be substantiated.

We did not use the Health on the Net Foundation HONcode (http://www.healthonnet.org/HONcode/Conduct.html) to assess websites, as it was outside the scope of this investigation, which may be a limitation of our study. The Health on the Net Foundation promotes the provision of high-quality health information. Adherence to the HONcode requires websites to include statements on attribution (HON Code principle 4): “Cite the source(s) of published information, date medical and health pages.” In addition, websites should also adhere to the principle of justifiability: “any claims relating to the benefits/performance of a specific treatment, commercial product or service will be supported by appropriate, balanced evidence in the manner outlined in Principle 4.” Our current results suggest that none of the websites we reviewed would meet the HONcode requirements.

Context of previous findings

Previous studies have shown that couples undergoing reproductive treatment are not well informed, particularly when it comes to the risks of treatment.24 A Dutch questionnaire survey of 1499 couples concluded that information provision for infertile couples is currently poor and in need of improvement: on average only half were aware of national fertility guideline-based recommendations,25 and strategies to improve uptake of guidelines had so far proved to be ineffective.26 Surveys have also shown that the success rates of reproductive treatments are often overestimated and that IVF couples often want to decide independently whether or not the particular risks and burden of interventions are acceptable.26 27 Qualitative studies have also shown that many women start IVF treatment with unrealistic expectations of the effectiveness of treatments.28

A survey of women undergoing fertility treatments in university hospitals and private fertility clinics in Canada reported that most women “wanted to share knowledge equally with their doctors about possible fertility treatments.” About half the woman wanted to make decisions mostly by themselves,29 which emphasises the importance of high-quality online information and access to relevant evidence. Previous work has found there is insufficient information on the web for couples to adequately inform themselves about available treatment options; but also that the overwhelming majority of infertile couples use the internet to look for information relevant to their situation; and those who do want a better understanding of fertility problems.30 This survey of 163 couples with fertility problems in the Netherlands reported that many couples felt the internet improved their knowledge about fertility treatments and facilitated decision-making.31 However, similar to our findings, an analysis of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology websites in the USA reported that the majority did not meet the American Medical Association (AMA) internet health information guidelines.31 Furthermore, that analysis of 263 sites found that the “quality of the hospital centers’ websites was better than that of private clinics”.

Implications

Current NICE guidance on fertility treatments, under ‘Principles of Care: Providing Information’, states that: “people should have the opportunity to make informed decisions regarding their care and treatment via access to evidence-based information.”23 The best current evidence shows that the information provided to potential patients on fertility centre websites is likely to be a primary information source for most individuals seeking medical help with fertility. This information should therefore ideally be of high quality, provide evidence for claims and state its limitations. This is currently not the case. Although in the UK it is mandatory for fertility clinics to publish their success rates, there is no requirement to cite national guidance or relevant evidence. There may be a need for regulatory oversight of the evidence on fertility interventions provided to couples by clinics through the web to ensure accuracy and relevance of the information. Ideally, regulatory bodies should require that information provided on these websites is accurate, reflects the highest level of available evidence and links to national guidance where appropriate. The situation in countries without such regulatory authorities as the HFEA may be worse, and it may be worthwhile replicating this research in other settings.

Conclusions

Many fertility centres in the UK offer a range of treatments in addition to standard IVF procedures, and for many of these interventions claims are made, implying or stating a benefit. In most cases, these claims are made without referring to any evidence to support them. Fertility treatment centres should provide information based on the best available evidence, citing sources including NICE guidance where appropriate, and should state the limitations of what is known about interventions offered. The fertility regulator takes an active role on ensuring data for success rates are correct and correctly reported; they could, and in our view should, do the same for evidence given by clinics to patients about the benefits and risks of interventions.

Footnotes

Contributors: CH and EAS conceived the study design, extracted and analysed the data. BG, KRM, CH and EAS all contributed to the methods and the writing of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Funding: This project received no specific funding. CH receives funding from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School of Primary Care Research; BG has received research funding from the Wellcome Trust, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, NHS England and the Health Foundation; and KRM is funded by a NIHR clinical lectureship.

Competing interests: EAS has no competing interests. CH has received expenses from the WHO and holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research and the WHO. BG has received research funding from the Wellcome Trust, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, NHS England and the Health Foundation; he receives personal income from speaking and writing for lay audiences on problems in science.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned by BMJOpen; externally peer reviewed. This work arose after BBC Panorama asked the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) to carry out an independent review of the evidence for fertility treatments additional to IVF. The BBC had no role in the review's protocol, methodology, or interpretation of findings but were kept aware of its progress. Deborah Cohen, the reporter of a BBC Panorama on fertility treatments, is a freelance editor at The BMJ.

Data sharing statement: A copy of the full supplementary table of data extraction of each website is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. http://cks.nice.org.uk/infertility#!topicsummary. Clinical knowledge summaries. Infertility (last revised April 2013).

- 2.NICE guidelines [CG156] fertility problems: assessment and treatment. Published date: February 2013. Last updated: August 2016. 1.2 Initial advice to people concerned about delays in conception. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156/chapter/Recommendations#initial-advice-to-people-concerned-about-delays-in-conception (accessed 18 Aug 2016).

- 3.NICE guidelines [CG156] Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. 2013 1.11 Access criteria for IVF. 1.11.1 Criteria for referral for IVF 1.11.1.3 [new 2013]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156/chapter/Recommendations#initial-advice-to-people-concerned-about-delays-in-conception (accessed 18 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). http://www.hfea.gov.uk/ (accessed 18 Aug 2016).

- 5.Some clinics using techniques not stringently tested. The great IVF rip-off. Daily Mail. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-3592661/The-great-IVF-rip-Clinics-preying-anxious-couples-selling-add-ons-not-work-harmful.html (accessed 18 Aug 2016).

- 6.HFEA. Reproductive immunology—natural killer cells—fertility. http://www.hfea.gov.uk/fertility-treatment-options-reproductive-immunology.html (accessed 18 August 2016).

- 7.Heneghan C, Spencer EA, Bobrovitz N et al. . Analysis of the evidence-base for IVF interventions offered in UK fertility centres. BMJ 2016036242.R2 10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nastri CO, Lensen SF, Gibreel A et al. . Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(3):CD009517 10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potdar N, Gelbaya T, Nardo LG. Endometrial injury to overcome recurrent embryo implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2012;25:561–71. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bontekoe S, Blake D, Heineman MJ et al. . Adherence compounds in embryo transfer media for assisted reproductive technologies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(7):CD007421 10.1002/14651858.CD007421.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carney SK, Das S, Blake D et al. . Assisted hatching on assisted conception (in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(12):CD001894 10.1002/14651858.CD001894.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souza Setti A, Ferreira RC, Paes de Almeida Ferreira Braga D et al. . Intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome versus intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection outcome: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2010;21:450–5. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antinori M, Licata E, Dani G et al. . Intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection: a prospective randomized trial. Reprod Biomed Online 2008;6:835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karimzadh MA, Ayazi Rozbahani M, Tabibnejad N et al. . Endometrial local injury improves the pregnancy rate among recurrent implantation failure patients undergoing in vitro fertilisation/intra cytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomised clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:677–80. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barash A, Dekel N, Fieldust S et al. . Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 2003;79:1317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartoov B, Berkovitz A, Eltes F et al. . Real-time fine morphology of motile human sperm cells is associated with IVFICSI outcome. J Androl 2002;23:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Aldo PB et al. . Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2030–6. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou L, Li R, Wang R et al. . Local injury to the endometrium in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cycles improves implantation rates. Fertil Steril 2008;89:1166–76. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartoov B, Berkovitz A, Eltes F et al. . Pregnancy rates are higher with intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection than with conventional intracytoplasmic injection. Fertil Steril 2003;80:1413–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chian RC, Huang JY, Tan SL et al. . Obstetric and perinatal outcome in 200 infants conceived from vitrified oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online 2008;16:608–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meseguer M, Rubio I, Cruz M et al. . Embryo incubation and selection in a time-lapse monitoring system improves pregnancy outcome compared with a standard incubator: a retrospective cohort study. Fertil Steril 2012;98:1481–9.e10. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun HX, Hu YL, Zhang NY et al. . A retrospective clinical study on effects of hyaluronan-containing transfer medium on implantation, pregnancy and delivery. IFFS 2010 (conference poster abstract). http://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/9085.pdf, pp 66/147) (accessed August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.NICE guidelines [CG156] Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. Published February 2013, last updated August 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156?unlid=373307668201622815432 (accessed 18 Aug 2016).

- 24.Rauprich O, Berns E, Vollmann J. Information provision and decision-making in assisted reproduction treatment: results from a survey in Germany. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2382–91. 10.1093/humrep/der207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mourad SM, Hermens RP, Cox-Witbraad T et al. . Information provision in fertility care: a call for improvement. Hum Reprod 2009;24:1420–6. 10.1093/humrep/dep029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mourad SM, Hermens RPMG, Liefers J et al. . A multi-faceted strategy to improve the use of national fertility guidelines; a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2011;26:817–26. 10.1093/humrep/deq299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoebel-Richter Y, Geue K, Borkenhagen A et al. . What do you know about reproductive medicine?—results of a German representative survey. PLoS One 2012;7:e50113 10.1371/journal.pone.0050113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peddie VL, van Teijlingen E, Bhattacharya S. A qualitative study of women's decision-making at the end of IVF treatment. Hum Reprod 2005;20:1944–51. 10.1093/humrep/deh857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart DE, Rosen B, Irvine J et al. . The disconnect: infertility patients’ information and the role they wish to play in decision making. Medscape Womens Health 2001;6:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haagen EC, Tuil W, Hendriks J et al. . Current internet use and preferences of IVF and ICSI patients. Hum Reprod 2003;18:2073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang JYJ, Discepola F, Al-Fozan H et al. . Quality of fertility clinic websites. Fertil Steril 2005;83:538–44. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table1.pdf (74.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table2.pdf (99.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table3.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013940supp_table4.pdf (58.6KB, pdf)