Abstract

Objectives

General practitioners (GPs) play a key role in heart failure (HF) management. Despite multiple guidelines, the management of patients with HF in primary care is suboptimal. Therefore, all the qualitative evidence concerning GPs’ perceptions of managing HF in primary care was synthesised to identify barriers and facilitators for optimal care, and ideas for improvement.

Design

Qualitative evidence synthesis.

Methods

Searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and CINAHL databases up to 20/12/2015 were conducted. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme's checklist for qualitative research was used for quality assessment. Thematic analysis was used as method of analysis.

Results

Of 5427 articles, 18 qualitative articles were included. Findings were organised in HF-specific factors, patient factors, physician factors and contextual factors. GPs’ uncertainty in all areas of HF management was highlighted. HF management started with an uncertain diagnosis, leading to difficulties with communication, treatment and advance care planning. Lack of access to specialised care and lack of knowledge were identified as important contributors to this uncertainty. In an effort to overcome this, strategies bringing evidence into practice should be promoted. GPs expressed the need for a multidisciplinary chronic care approach for HF. However, mixed experiences were noted with regard to interprofessional collaboration.

Conclusions

The main challenges identified in this synthesis were how to deal with GPs’ uncertainty about clinical practice, how to bring evidence into practice and how to work together as a multiprofessional team. These barriers were situated predominantly on the physician and contextual level. Targets to improve GPs’ HF care were identified.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This qualitative evidence synthesis is the first to collect and review the existing qualitative research about general practitioners’ (GPs') perceptions of managing chronic heart failure in primary care.

Knowledge in this area is recent: all of the included articles were published after 2001, with a majority of studies published after 2011 (13/18).

The synthesis of qualitative research is an expanding and evolving methodological area. ENhancing TRansparancy in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement recommendations were followed in order to enhance maximum transparency in reporting the synthesis.

Devising a search strategy was challenging since methodological filters were not useful.

The results of this synthesis are based largely on studies undertaken in the UK (9 articles) and Canada (4 articles), which may impact the transferability of findings. Therefore, the context of the included studies was provided to enable readers to judge for themselves whether or not it is similar to their own.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a highly prevalent disease, affecting the elderly in particular.1 2 Early diagnosis of HF is important so that treatment can be initiated on time in order to delay progression to overt HF.1 In Europe, most patients with HF first present in primary care.3 However, HF diagnosis and treatment is often inadequate in primary care.3–5 Natriuretic peptides and echocardiography, recommended for the diagnosis of HF1 are underused by general practitioners (GPs).6 Additionally, a ‘seamless’ system of care, integrating both community and hospital care has been shown to reduce HF hospitalisation and mortality in patients discharged from hospital.1 7 8 Despite the evidence, multidisciplinary management programmes are still not widely implemented as usual care.

The reasons behind this evidence-practice mismatch have been addressed in qualitative studies exploring the barriers and facilitating factors primary care professionals experience in the management of chronic heart failure (CHF). Special interest is focused on the perceptions of the GP, who plays a key role in the coordination of care for patients with long-term conditions in primary care.9 Much qualitative research has been undertaken to respond to this issue, but to date no review article has synthesised all the previous research.

Therefore, this article synthesises the GPs' perspectives on current management of CHF in primary care. We conducted a qualitative evidence synthesis to understand how GPs experience the diagnosis and management of CHF in daily practice, to identify the barriers and facilitators for optimal care, and to explore their ideas in order to overcome the identified obstacles.

Methods

Design

The synthesis of the findings of primary qualitative studies is emerging as an important source of evidence for healthcare and policy.10 11 A qualitative evidence synthesis can pull together data across different contexts, generate new theoretical or conceptual models, identify research gaps, and provide evidence for the development, implementation and evaluation of health interventions.10 To ENhance Transparency in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research the ENTREQ statement was developed. The recommendations of this statement were followed to report our synthesis.10

Search strategy

A comprehensive preplanned search of the literature was undertaken in four databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and CINAHL, all from inception to 20 December 2015. Search terms were categorised in three groups:

Group 1: HF

Group 2: GPs

Group 3: Qualitative research

These groups were combined with ‘AND’ to complete the search (see online supplementary appendix 1 for search strategy). A cited reference search of selected studies was conducted (in the Web of Science database) and reference lists of selected articles were manually searched for identification of additional sources.

bmjopen-2016-013459supp_appendices.pdf (460.3KB, pdf)

Study selection

The following definition was used to select studies: ‘papers with a focus on GPs’ experiences and/or perceptions of CHF and its management in primary care’. For inclusion in the review a study had to use qualitative methods of data collection and analysis, either as a stand-alone study or as a discrete part of a larger mixed-method study. Studies using mixed methods were included only if qualitative findings were presented separately from quantitative results. Descriptive papers, editorials, and opinion papers were excluded. To be included in our analysis, at least one study participant had to be a GP. If a study used a mixed sample of participants (eg, patients, family caregivers, nurses, GPs and cardiologists), it had to allow clear extraction of the GP's opinion: if data were not illustrated by a direct quotation from a GP, the study was excluded. Only qualitative research performed in outpatient settings was included. Hospital settings were excluded. Studies that focused on different conditions (eg, HF, dementia and cancer) were included if the results related to CHF were reported separately from the other conditions. Since our research question concerned the GPs' perspectives on current management of CHF, we excluded evaluation studies of interventions that had not yet been implemented in usual care. Articles in languages other than English were considered if the English translation of the abstract met the above-stated inclusion criteria.

The first reviewer (SVR) divided the resulting articles into three categories (definitely excluded, included and in doubt) based on title and abstract. All studies in the last two categories were checked by the second reviewer (MS). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (BV). Full texts of all included articles and all articles in doubt were retrieved. Two reviewers (SVR and BV) read the articles and checked the inclusion criteria. A third person (MS or MV) considered studies on which there was a lack of agreement, and a final decision was made after discussion. A log was kept of the excluded articles, with the reasons for exclusion.

Critical appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was used to assess the quality of the included studies (see online supplementary appendix 2). This instrument is easily accessible online and clearly defines the meaning behind each individual criterion listed.12 Two independent reviewers (SVR and MS) assessed the quality of included articles and results were discussed to reach consensus. Only moderate-to-high quality studies were included to ensure the validity of the included results.13

Data extraction

Background information on each study (study aim, origin, study setting, participants, methods used for data collection and analysis) was extracted from each paper. Two approaches were used to extract qualitative evidence from the included studies. If only GPs participated in the study and HF was the only condition studied, all themes or other qualitative data identified in the primary study and relevant to the research questions of the review were extracted, regardless of whether they were illustrated by a direct quotation.14 If groups other than GPs participated or conditions other than HF were targeted, only data illustrated by a direct quotation from a GP, or by a direct quotation related to HF respectively, were extracted. For each paper, these data were extracted by SVR and then checked by a second reviewer (MS).

Data analysis and synthesis

Thematic analysis was used as a method for analysis and synthesis of the selected studies. Thematic analysis is a tried and tested method that preserves an explicit and transparent link between conclusions and text of primary studies; as such, it preserves principles that have traditionally been important to systematic reviewing.15 Thematic synthesis comprises three stages: the ‘line-by-line’ coding of text; the development of ‘descriptive’ themes; and the generation of ‘analytical’ themes. While the development of descriptive themes remains ‘close’ to the primary studies, the analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation whereby the reviewers ‘go beyond’ the primary studies and generate new interpretive constructs, explanations or hypotheses.15

We entered all the results of the studies verbatim into QSR's Nvivo V.11 software for qualitative data analysis. After familiarisation with the data, two reviewers (SVR and MS) independently coded each line of text according to its meaning and content. Codes were created inductively. After reading and coding the findings of four studies, the two researchers discussed and compared the codes for similarities and differences until a primary coding framework was constructed. Subsequently, the findings of the other studies were independently read and coded. On various occasions the two reviewers discussed their respective coding frameworks to reach consensus. Codes were added, modified or merged where necessary. This process resulted in a tree structure with several layers for organising the descriptive themes. From these, a set of analytical themes emerged that were discussed by the whole research team (SVR, MS, BV and MV).

Results

Results of the database searches

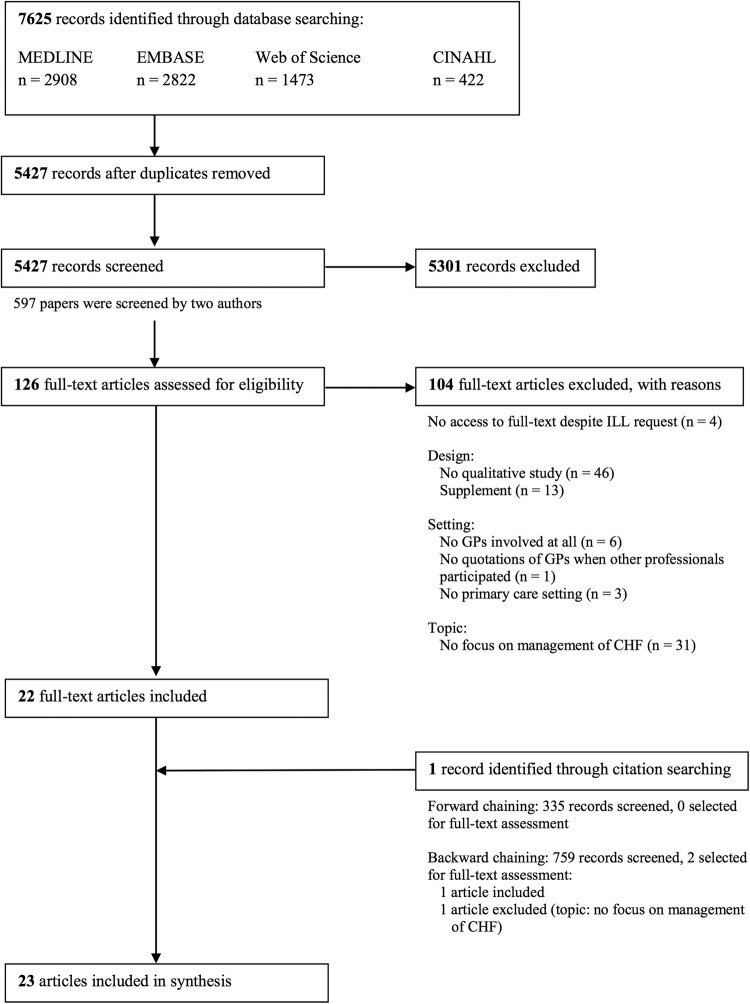

A PRISMA flow diagram16 of study selection is presented in figure 1. Of 5427 records, 23 articles met the inclusion criteria. One article was identified through citation searching.17 This article was not retrieved by the database searches.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. CHF, chronic heart failure; GPs, general practitioners; ILL, interlibrary loan.

Critical appraisal

The quality of all included studies was evaluated using the CASP checklist for qualitative research (table 1).12 Five studies were recognised as low-quality studies and were excluded.18–22 Eventually, 18 articles were included in this qualitative evidence synthesis. Online supplementary appendix 3 summarises the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Critical appraisal using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research

| CASP questions |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5* | 6 | 7 | 8* | 9* | 10 | Quality rating | Comments |

| De Vleminck et al23 | x | x | x | x | x | ? | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Fuat et al24 | x | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | x | H | |

| Kasje et al18 | x | x | / | / | / | / | / | x | / | x | L | Exclusion |

| Khunti et al25 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Peters-Klimm et al19 | x | x | x | x | / | / | / | x | / | / | L | Exclusion |

| Phillips et al26 | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | / | x | x | M | |

| Waterworth and Gott27 | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | / | x | M | |

| Ahmedov et al28 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Barnes et al29 | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Boyd et al20 | x | x | x | x | / | / | x | / | / | / | L | Exclusion |

| Browne et al45 | x | x | x | x | x | ? | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Close et al30 | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Glogowska et al31 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Hancock et al6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Hanratty et al32 | x | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | x | H | |

| Hayes et al33 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Heckman et al34 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Kavalieratos et al35 | x | x | x | x | x | / | x | x | x | x | H | |

| MacKenzie et al21 | x | x | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | x | L | Exclusion |

| Newhouse et al17 | x | x | x | x | / | ? | x | x | x | x | M | |

| Simmonds et al36 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Tait et al37 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | H | |

| Toal et al22 | x | x | x | x | / | / | / | / | / | x | L | Exclusion |

*Questions that were given more weight by the reviewers: number 5 ‘Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?’; number 8 ‘Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?’; and number 9 ‘Is there a clear statement of findings?’.

x=yes; /=no; ?=cannot tell.

H, high; L, low; M, moderate.

Data analysis and synthesis

A comprehensive overview of all identified themes is provided in table 2. In this table, themes were organised into HF-specific and patient factors (non-modifiable) and physician and contextual factors (modifiable) to facilitate recognition of modifiable factors. Additionally, three overarching themes were identified for synthesising GPs' perceptions of managing patients with CHF in primary care: (a) uncertainty about clinical practice; (b) interdisciplinary collaboration and (c) ideas for improvement. A narrative summary of these themes was provided below.

Table 2.

Thematic matrix: GPs’ perceptions of managing chronic HF in primary care

| HF-specific factors | Patient factors | Physician factors | Contextual factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of guidelines | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

||

| Facilitators |

|

|||

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|

||

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Facilitators |

|

|

||

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|

||

| Communication with patients | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Facilitators | ||||

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|||

| Treatment | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Facilitators |

|

|

|

|

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|||

| ACP | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Facilitators |

|

|

||

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|||

| Interdisciplinary collaboration | ||||

| Barriers |

|

|

||

| Facilitators |

|

Specific context of care homes

|

||

| Ideas for improvement |

|

|

||

derived from data of study/studies performed in UK;

derived from data of study/studies performed in UK;  derived from data of study/studies performed in Australia;

derived from data of study/studies performed in Australia;  derived from data of study/studies performed in Canada;

derived from data of study/studies performed in Canada;  derived from data of study/studies performed in Uzbekistan.

derived from data of study/studies performed in Uzbekistan.

ACE-I, ACE inhibitors; ACP, advance care planning; GP, general practitioner; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LTC, long-term care.

Theme 1: Uncertainty about clinical practice

Subtheme 1.1: Value of clinical guidelines

Most physicians were unfamiliar with existing guidelines about the diagnosis and management of HF.6 24 25 28 34 Underuse of guidelines could be partly explained by the GPs' feeling that they were being overloaded with information and experienced ‘guideline fatigue’.6 24 Additionally, GPs felt that guidelines were rarely applicable to real-world practice.6 24 They ‘rarely cover options in polypharmacy’ and ‘a lot of people do not fit into them, the little boxes’.6

On the other hand, some GPs recognised and worried about the ‘rapidity of change in all fields’ and believed that ‘[they] owe it to [their] patients’ to be in touch.24 They expressed the view that using guidelines led to more confident decision-making.6 24

Subtheme 1.2: Difficult diagnosis

Throughout all studies GPs expressed the feeling that HF was a difficult diagnosis. The main difficulties in accurately diagnosing HF were the blinding of the disease by other conditions and the lack of specificity of the symptoms, particularly in the early stages.24–26 29 34 This was especially the case in elderly patients with comorbid conditions.24–26 34

The biggest problem is that it's always inevitably older people who get it. It's a co-pathology intermingled with other things, and that makes it often quite difficult to disentangle.24

GPs attached great importance to a clinical assessment when diagnosing HF.24–26 34 To the extent that HF was a purely clinical diagnosis for some GPs, other GPs did use additional tests but a wide variety was noted in their choices.24–26 34 Many GPs mentioned that they would arrange a chest X-ray and some would arrange a 12-lead electrocardiogram.25 34 Only a few GPs reported sending a patient for an echocardiography to confirm a diagnosis of HF.24–26 34 Several reasons were given as to why echocardiography is not more commonly used in assessing patients with suspected HF: difficulties in accessing echocardiography services;24–26 34 a lack of confidence in interpreting test results when using open-access echocardiography;6 24 unawareness of the diagnostic benefits of echocardiograms;24–26 34 and a view that echocardiography is not always warranted, especially in obvious cases.25 26 34

Usually the diagnosis is made—at least by myself—clinically, because I, I don't think I sent anybody for … an echo. That's how you would theoretically make the diagnosis.34

Another obstacle to diagnosing HF in general practice was not having enough time to deal with patients suspected of having HF, even if GPs were aware of the evidence concerning the validity of signs or investigations.24–26

Finally, not all GPs were confident about diagnosing CHF6 24 28 and for some, the diagnosis could only be made by cardiologists.24 28

Well, you know, we GPs… can't diagnose CHF… After referral to a cardiologist, we write down that diagnosis, control those maintaining medications.28

Subtheme 1.3: Difficulties in communication with patients

Since GPs were uncertain about the diagnosis and prognosis of HF, they found it difficult to relay information back to patients.29 Additionally, all GPs felt that the term ‘heart failure’ was unhelpful in explaining the diagnosis and prognosis to patients. GPs regarded it as a ‘loaded’ term,31 having an effect on patients that was similar to being told they had cancer.24 29 31 36 To avoid upsetting patients and extinguishing hope, some clinicians talked about HF in euphemistic terms, such as having an ‘ageing heart’, ‘stiff heart’ or ‘heart not pumping efficiently’.29 36

GPs recognised a conflict in balancing prognostic information with symptom treatment: while patients may live with HF for a long time, they realised it was necessary to emphasise the importance of taking appropriate medication.24 29 Some GPs spoke about addressing the question of prognosis over time in response to changing circumstances, particularly where patients might be approaching the end of their life.31

It could be another 10 years before they progress and something else would kill them first, so you don't want to give undue alarm, but at the same time… in order to entice them to take their medications, you probably do need to explain the gravity of the situation. It's a very fine balance.29

Subtheme 1.4: Treatment issues

Uncertainty about diagnosis also cast doubts on the development of treatment strategies.24 25 Additionally, GPs encountered difficulties associated with comorbidities and polypharmacy, especially in elderly patients.6 24 26 31 36 Moreover, several GPs saw ageism as a consideration for a less aggressive approach.24–26 30 34

I think there is an ageist agenda with it as well because you know somebody of 60 who has got heart failure you’re going to be much more aggressive with than someone who is 78, not just in terms of making the diagnosis but the investigations and treatment.24

And again, GPs recognised that they lacked the time needed to ensure efficient and effective follow-up and accurate monitoring of patients with HF.6 33 37

A feeling predominated in some practices that HF should be managed in secondary care:6 24 33 “Can we adequately manage heart failure in general practice, given the modern advances that we are all unsure about?”.24 Indeed, most GPs were not fully aware of the possible treatment options.6 23–26 34 Some GPs were happy to keep patients on diuretics only, possibly unaware of the potential benefits of ACE inhibitors (ACE-I) and β-blockers.23–26 34 Other reasons for not prescribing ACE-I or β-blockers in patients with newly diagnosed HF were: concerns about possible side effects;6 24–26 31 worries about starting treatment in primary care as opposed to in hospital, partly because of previous teaching and a fear that patients might collapse in the community setting;6 24 26 and the burden of monitoring when titrating the medications.6 24 25 Even when ACE-I were initiated, GPs were cautious about using high doses.24–26

The danger of impaired renal function with high doses of not only the diuretics but the ACE inhibitors as well juggling doses of ACE inhibitors against diuretics, up and down, checking potassium. I do find some of those conflicts difficult to resolve.6

Not all GPs shared these views,24–26 34 offering comments such as: “The evidence for their [ACE-I] use is very good, and if there is a side effect then I will look for an alternative”;26 and “Getting them on an ACE inhibitor and β-blockers are fairly simple things to do”.34

Most GPs had little knowledge of the role of agents other than diuretics, ACE-I and β-blockers,6 24 34 and some GPs still treated HF as an acute illness.33 34

I think one thing that may be lost here, and this may be part of the overall management: you make them better by treating the acute symptoms but maybe there's something lost there that you don't go on to manage the heart failure itself … because you make them better, you think you've done what you need to do, but maybe you should be looking at, you know: is this person on an ACE, and if not, should you be starting one?34

Subtheme 1.5: Advance care planning (ACP) is not (timely) initiated

The majority of GPs acknowledged that the stage of advanced illness was too late to initiate ACP, but, in practice, end-of-life care issues were generally raised when the patient's condition was obviously declining after numerous acute hospital admissions.23 31 The timing of ACP was experienced as difficult by many GPs, because: unlike cancer, the diagnosis of HF does not start with bad news; the path of CHF is unpredictable without clear key moments; and less attention is paid to ACP in chronic diseases.6 23 29 31 32 35

The prognosis is so variable with mild heart failure, and often, the people are very old anyway and something else is going to get them first, and you know, you just address it on a pragmatic level rather than spelling out exactly what the course is likely to be.29

Theme 2: Interdisciplinary collaboration

Subtheme 2.1: Limited access to specialised care with long waiting lists for referral

Waiting lists and the poor local availability of specialised care, such as cardiology services, open-access echocardiography, HF clinics and HF nursing teams, had a negative effect on GPs' decisions to refer patients with suspected HF.6 24–26 34 36 These barriers to service usage were attributed to the organisation of healthcare systems, varying from country to country (table 2).

The mammoth wait makes using this service [HF clinic] impractical.6

Subtheme 2.2: GPs' attitudes towards multidisciplinary collaboration

Some GPs feared that the organisation of care, with an emphasis on specialist HF services and task delegation, might lead to the de-skilling of GPs.6 A few practitioners already felt that other healthcare providers did not fully trust their clinical competence.25 36 A particular concern among GPs was the fear of losing patients to specialists:32 37 “There are some specialties where the specialist basically takes over the care of the patient, and the patient disappears”.37

The feeling predominated that specialist assistance led to fragmented care instead of integrated care, and that the involvement of multiple specialists, each with a narrow clinical focus, might paradoxically further complicate the management of patients with HF.17 34

So we really do sometimes need a person who specializes in one or another field to try to build things on, because sometimes a patient is going [to a specialist] and a cardiologist will take over initially. Then he [cardiologist] passes on to the diabetologist. Then he passes on to the renal specialist. So sometimes one [specialist] fixes one thing and gets them [residents] stabilized, then passes on to the next.34

GPs also regretted the variability in clear reports and interprofessional communication.24 34 37 These experiences influenced referral and effective collaboration.

On the other hand, many GPs also had positive experiences in working with other healthcare providers. In these situations the attitude of GPs and other professionals influenced interprofessional collaboration positively.27 34 37

Yeah, he [specialist] called this morning, I called him on my cell phone and he called back by lunch.34

I trust the PSWs [personal support workers] more than anybody, more than the nurses, more than myself, because they see them [residents of care homes] all the time; they are the ones doing care.34

Theme 3: Ideas for improvement

Subtheme 3.1: Need for education and locally drafted guidelines

The majority of GPs acknowledged the need for education for GPs to overcome their uncertainty about clinical practice.6 29 33

If primary care physicians were taught and educated and encouraged to seek these things out (signs of fluid retention) we may be able to do a better job at avoiding hospital visit with frank failure.33

Some GPs suggested the development of locally drafted guidelines to ensure a locality based, contextualised approach to overcome local organisational factors around the provision of specialised services and professional interactions between primary and secondary care.24

Subtheme 3.2: Promoting a holistic and chronic care approach

Some GPs emphasised the active role that community-based healthcare providers, including GPs, nurses and community pharmacists, should play in HF care. The paradigm shift from episodic diabetes treatment and management to a chronic care approach was alluded to as an example for HF.33 The need for more specialist HF nurses was expressed, particularly as a means of supporting the primary healthcare team through collaborative action.27

I really think that the cardiologist have to press upon the primary care physicians saying “Listen you can prevent emergency room visits in heart failure […] by just taking a little extra time to check over your patients. Just like we do for Diabetes […] the heart failure patient should have dedicated visit specifically for heart failure.33

Having maybe specialist nurses in the management of heart failure who would do house calls and help monitor these patients would help us.27

Discussion

This evidence synthesis highlights GPs' uncertainty about managing patients with CHF in general practice. The non-discriminating symptoms and signs, and the difficulties associated with elderly patients and comorbidities, made HF difficult to diagnose. GPs were unfamiliar with the natural history of CHF, lacked the expertise to diagnose and manage CHF, and were not fully aware of relevant research evidence and guidelines, despite their availability. The need for education is expressed by GPs, as well as the importance of a holistic and chronic care approach.

Variable access to diagnostic services and specialised care shaped practice and decision-making processes among GPs. They expressed their concerns that interdisciplinary collaboration would result in de-skilling and losing patients to specialists, and admitted that interdisciplinary collaboration was influenced by previous positive or negative experiences. The idea of locally drafted guidelines was proposed to overcome these obstacles.

This qualitative evidence synthesis is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to collect and review the existing qualitative research about GPs' perceptions of managing CHF in primary care. Knowledge in this area is recent: all of the included articles were published after 2001, with a majority of studies published after 2011 (13/18). The synthesis of qualitative research is an expanding and evolving methodological area. ENTREQ statement recommendations were followed in order to enhance maximum transparency in reporting the synthesis.10

However, a few limitations of the present study should be noted. First, devising a search strategy was challenging. Initially, methodological filters were tested, but found to be unhelpful as the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) ‘Qualitative Research’ was only introduced in 2003, and even after 2003 papers were not identified appropriately as qualitative.38 Therefore, the search was expanded, and backward and forward citation searching was performed, in order to be as inclusive as possible (see online supplementary appendix 1).

Second, quality assessment of qualitative research is contentious. The approach chosen aimed to exclude low-quality studies and avoid unreliable conclusions. A potential risk of this approach is that valuable insights from the excluded studies are lost; however, the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group recommends this method, emphasising methodological soundness of studies.13

Third, the results of this synthesis are based largely on studies undertaken in the UK (nine articles) and Canada (four articles), which may impact the transferability of findings. Additionally, HF research, guidelines and resources have evolved since 2001. Consequently, some of the findings in older studies may not reflect the current situation. Therefore, the context of the included studies was provided to enable readers to judge for themselves whether or not it is similar to their own.

The main challenges identified in this synthesis were how to deal with GPs' uncertainty about clinical practice, how to bring evidence into practice and how to work together as a multiprofessional team to provide good-quality coordinated care. Identified obstacles were organised into HF-specific factors, patient factors, physician factors and contextual factors. The majority of influenceable factors were contextual and physician related: these factors could be seen as possible targets for implementation strategies to improve HF management.

First, uncertainty about clinical practice started with uncertainty about HF diagnosis. Echocardiography is needed to objectify the diagnosis of HF; nonetheless, GPs experienced several barriers to referring patients for echocardiography, such as a lack of availability of echocardiography. Indeed, in most European countries, echocardiography was either not available to more than half of the primary care physicians within 1 month, or not available at all.39 In response, efforts have been made in the last decade to improve access to echocardiography services, for example in the UK, by introducing open-access echocardiography.6 However, recent qualitative studies have shown that open-access echocardiography did not always meet the need because many GPs still preferred to refer the patient to a cardiologist or specialist HF clinic due to a lack of confidence in interpreting test results.6 24 Additionally, guidelines advocate the use of natriuretic peptides as a rule-out test to limit the number of cases needing echocardiography.1 However, surprisingly, in our synthesis not one GP commented on his or her experiences with the use of this biomarker. Hancock et al6 did cover this subject in their survey showing that 20–30% of GPs used natriuretic peptides in the diagnosis of HF and the same percentage again would use them if they were readily available. It would be interesting to investigate GPs' experiences with the use of natriuretic peptides for the diagnosis and management of HF in daily practice.

Second, it was remarkable that many GPs expressed the need for education to overcome this uncertainty, despite widespread availability of evidence-based HF guidelines. Indeed, published research evidence does not automatically diffuse into clinical practice.40 Given the barriers to guidelines usage identified in this synthesis, there is no need for additional guidelines as GPs already felt ‘overloaded with information’.6 24 Some GPs did express the need to translate existing HF guidelines to the local situation, with input from primary and secondary care professionals.24 Another way to improve translation of guidelines into practice could be the implementation of a clinical decision support system (CDSS) integrated in the GPs' electronic health record. Guidelines combined with expert advice via a CDSS are a way of providing tailored management and have been proven to increase GPs' confidence in the diagnosis and management of CHF.41–43

Third, a multidisciplinary approach to HF management is promoted by research results and HF guidelines.1 7 8 GPs agreed with the need for a multidisciplinary chronic care approach for HF, but they acknowledged difficulties in interdisciplinary collaboration and communication. GPs expressed the fear of losing their central role and becoming de-skilled, and were concerned that specialist assistance led to fragmented care instead of integrated care.6 17 32 34 37 On the other hand, ease of access and former positive experiences positively influenced collaboration.27 34 37 This is in line with previous studies that also emphasised the importance of contextual tensions and interprofessional relationships that can have both positive and negative influences on effective collaboration.37 44 When establishing new initiatives for HF improvement programmes, these tensions and relationships should be taken into account since a positive attitude towards multidisciplinary collaboration is a prerequisite for success.

In conclusion, this evidence synthesis highlighted GPs' uncertainty in all areas of HF management starting with diagnostic uncertainty. Lack of access to specialised care and lack of knowledge were identified as important contributors to this uncertainty. Lack of access to specialised care could partly be countered by promoting implementation of natriuretic peptides in primary care as a rule-out test to reduce the number of patients needing echocardiography. Additionally, strategies bringing evidence into practice should be promoted, such as locally drafted guidelines or CDSS integrated in the electronic health record. GPs expressed the need for a multidisciplinary chronic care approach for HF. However, mixed experiences were noted with interprofessional collaboration. When establishing new initiatives for HF improvement programmes, the barriers and facilitators found in this evidence synthesis should be taken into account.

Footnotes

Contributors: All named authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this qualitative evidence synthesis and have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript. SVR and MS contributed equally as first authors in the search strategy, study selection, critical appraisal, data collection, data analysis and drafting of the work. MV and BV assisted the whole process, contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically revised the work. BA critically revised the work.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. , Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MC et al. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure the Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1614–19. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JG, Cohen-Solal A, Aguilar JC et al. Management of heart failure in primary care (the IMPROVEMENT of Heart Failure Programme): an international survey. Lancet 2002;360:1631–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11601-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krum H, Tonkin AM, Currie R et al. Chronic heart failure in Australian general practice. The Cardiac Awareness Survey and Evaluation (CASE) Study. Med J Aust 2001;174:439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlstrom U, Hakansson J, Swedberg K et al. Adequacy of diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure in primary health care in Sweden. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:92–8. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock HC, Close H, Fuat A et al. Barriers to accurate diagnosis and effective management of heart failure have not changed in the past 10 years: a qualitative study and national survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003866 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:774–84. 10.7326/M14-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S et al. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:810–19. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Primary health care: now more than ever. World Health Report 2008. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/ (30 Mar 2016).

- 10.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ring N, Ritchie K, Andava L et al. A guide to synthesising qualitative research for researchers undertaking health technology assessments and systematic reviews 2011. http://www.nhshealthquality.org/nhsqis/8837.html (7 Jan 2016).

- 12.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist. Website Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) 2013. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf (7 Jan 2016).

- 13.Hannes K. Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Version 1] 2011. http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance, Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group. (7 Jan 2016).

- 14.Noyes J, Lewin S. Chapter 5: Extracting qualitative evidence. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Version 1] 2011. http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance. (7 Jan 2016).

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newhouse IJ, Heckman G, Harrison D et al. Barriers to the management of heart failure in Ontario long-term care homes: an interprofessional care perspective. J Res Interprof Pract Educ 2012;2:278–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasje WN, Denig P, de Graeff PA et al. Perceived barriers for treatment of chronic heart failure in general practice; are they affecting performance? BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:19 10.1186/1471-2296-6-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters-Klimm F, Natanzon I, Müller-Tasch T et al. Barriers to guideline implementation and educational needs of general practitioners regarding heart failure: a qualitative study. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2012;29:Doc46 10.3205/zma000816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd KJ, Worth A, Kendall M et al. Making sure services deliver for people with advanced heart failure: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients, family carers, and health professionals. Palliat Med 2009;23:767–76. 10.1177/0269216309346541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie E, Smith A, Angus N et al. Mixed-method exploratory study of general practitioner and nurse perceptions of a new community based nurse-led heart failure service. Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toal M, Walker R. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in the treatment of heart failure in general practice in north Cumbria. Eur J Heart Fail 2000;2:201–7. 10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00071-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Beernaert K et al. Barriers to advance care planning in cancer, heart failure and dementia patients: a focus group study on general practitioners’ views and experiences. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e84905 10.1371/journal.pone.0084905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuat A, Hungin AP, Murphy JJ. Barriers to accurate diagnosis and effective management of heart failure in primary care: qualitative study. BMJ 2003;326:196 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khunti K, Hearnshaw H, Baker R et al. Heart failure in primary care: qualitative study of current management and perceived obstacles to evidence-based diagnosis and management by general practitioners. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:771–7. 10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips SM, Marton RL, Tofler GH. Barriers to diagnosing and managing heart failure in primary care. Med J Aust 2004;181:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waterworth S, Gott M. Involvement of the practice nurse in supporting older people with heart failure: GP perspectives. Prog Palliative Care 2012;20:7–12. 10.1179/1743291X11Y.0000000019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmedov M, Green J, Azimov R et al. Addressing the challenges of improving primary care quality in Uzbekistan: a qualitative study of chronic heart failure management. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:458–66. 10.1093/heapol/czs091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S et al. Communication in heart failure: perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:482–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Close H, Hancock H, Mason JM et al. “It's somebody else's responsibility”—perceptions of general practitioners, heart failure nurses, care home staff, and residents towards heart failure diagnosis and management for older people in long-term care: a qualitative interview study. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:69 10.1186/1471-2318-13-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glogowska M, Simmonds R, McLachlan S et al. Managing patients with heart failure: a qualitative study of multidisciplinary teams with specialist heart failure nurses. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:466–71. 10.1370/afm.1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F et al. Doctors’ perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ 2002;325:581–5. 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes SM, Peloquin S, Howlett JG et al. A qualitative study of the current state of heart failure community care in Canada: what can we learn for the future? BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:290 10.1186/s12913-015-0955-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heckman GA, Boscart VM, McKelvie RS et al. Perspectives of primary-care providers on heart failure in long-term care homes. Can J Aging 2014;33:320–35. 10.1017/S0714980814000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS et al. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000544 10.1161/JAHA.113.000544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmonds R, Glogowska M, McLachlan S et al. Unplanned admissions and the organisational management of heart failure: a multicentre ethnographic, qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007522 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tait GR, Bates J, LaDonna KA et al. Adaptive practices in heart failure care teams: implications for patient-centered care in the context of complexity. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8:365–76. 10.2147/JMDH.S85817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noyes J, Hannes K, Booth A et al. Chapter 20: Qualitative research and Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Version 5.3.0] 2015. http://qim.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance (7 Jan 2016).

- 39.Remme WJ, McMurray JJ, Hobbs FD et al. Awareness and perception of heart failure among European cardiologists, internists, geriatricians, and primary care physicians. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1739–52. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott IA, Glasziou PP. Improving effectiveness of clinical medicine: the need for better translation of science into practice. Med J Aust 2012;197:374–8. 10.5694/mja11.10365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tierney WM, Overhage JM, Takesue BY et al. Computerizing guidelines to improve care and patient outcomes: the example of heart failure. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1995;2:316–22. 10.1136/jamia.1995.96073834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leslie SJ, Hartswood M, Meurig C et al. Clinical decision support software for management of chronic heart failure: development and evaluation. Comput Biol Med 2006;36:495–506. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toth-Pal E, Wårdh I, Strender LE et al. A guideline-based computerised decision support system (CDSS) to influence general practitioners management of chronic heart failure. Inform Prim Care 2008;16:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tierney S, Kislov R, Deaton C. A qualitative study of a primary-care based intervention to improve the management of patients with heart failure: the dynamic relationship between facilitation and context. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:153 10.1186/1471-2296-15-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Browne S, Macdonald S, May CR et al. Patient, carer and professional perspectives on barriers and facilitators to quality care in advanced heart failure. PLoS One 2014;9(3):e93288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013459supp_appendices.pdf (460.3KB, pdf)