Abstract

Introduction

Improved understanding of risk factors for developing active tuberculosis (TB) will better inform decisions about diagnostic testing and treatment for latent TB infection (LTBI) in migrant populations in low-incidence regions. We aim to examine TB risk factors among the foreign-born population in British Columbia (BC), Canada, and to create and validate a clinically relevant multivariate risk score to predict active TB.

Methods and analysis

This retrospective population-based cohort study will include all foreign-born individuals who acquired permanent resident status in Canada between 1 January 1985 and 31 December 2013 and acquired healthcare coverage in BC at any point during this period. Multiple administrative databases and disease registries will be linked, including a National Immigration Database, BC Provincial Health Insurance Registration, physician billings, hospitalisations, drugs dispensed from community pharmacies, vital statistics, HIV testing and notifications, cancer, chronic kidney disease and dialysis treatment, and all TB and LTBI testing and treatment data in BC. Extended proportional hazards regression will be used to estimate risk factors for TB and to create a prognostic TB risk score.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the University of British Columbia Clinical Ethics Review Board. Once completed, study findings will be presented at conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. An online TB risk score calculator will also be created.

Keywords: latent tuberculosis infection, risk score

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest database of its size and scope which will give us a detailed understanding of tuberculosis disease risk in the foreign-born population of British Columbia.

This cohort represents near-complete capture of the demographic, immigration and healthcare service usage for more than 1 million people over a 28-year period.

Limitations may include incomplete and missing data associated with administrative data.

Introduction

Progress towards tuberculosis (TB) elimination in low TB-incidence regions has stalled, as the disease has increasingly concentrated in certain high-risk populations. Foreign-born populations are at particularly high TB risk in many low-incidence regions, with TB incidence often in excess of 20 times the non-indigenous, non-foreign-born population.1 To achieve TB elimination in low-incidence regions, new strategies that reduce TB incidence in foreign-born populations will be required.1

The WHO Framework for TB elimination in low-incidence regions highlights the increasing importance of diagnosis and management of latent TB infection (LTBI) in high-risk groups. Given the large proportion of foreign-born individuals with LTBI infection,2 widespread LTBI screening and treatment is unlikely to be practical or cost-effective.3–5 Instead, a strategy that focuses on people with highest TB risk should be considered.1 2 4–6

In the foreign-born population, most TB disease results from reactivation of LTBI acquired prior to immigration.7–11 Certain demographic features, such as birth country and time since immigration will influence TB risk, and comorbidities such as HIV and diabetes also influence TB risk.7 Which combination of these demographic and medical characteristics will place someone at highest risk for active TB remains somewhat unclear, and the cost-effectiveness of screening different populations is largely unknown.

Identifying the risk factors and knowledge of predicted risk of developing active TB will better inform decisions about diagnostic testing and treatment for LTBI among the foreign-born population. More specifically, improving our understanding of active TB risk will directly inform several priority actions of the WHO Framework for low-incidence regions and the US Preventive Services Task Force,6 by addressing special needs of migrants and targeting LTBI screening and treatment to high-risk populations.

Study objectives

Using linked person-level data, we will explore the relationship between medical and demographic risk factors that predict active TB incidence in a migrant population of British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Specific objectives are as follows:

to identify and describe demographic and medical risk factors for active TB among the foreign-born population in BC;

to create and validate a clinically relevant multivariate risk score to predict active TB among the foreign-born population in BC.

Ultimately, through identifying specific immigrant populations at highest risk for developing active TB and subsequent modelling of the cost-effectiveness of screening and treating these populations for LTBI, our goal is to identify the subset of high-risk migrants in BC that we can screen and treat within available resources to generate the highest yield in terms of preventing active TB.

Methods and analysis

Study setting

Canada is a low TB-incidence country, with the majority of TB cases (70%) diagnosed in persons born outside of Canada, many from high TB-incidence countries.12 BC is a low TB-incidence region with an annual TB incidence of 6.0 per 100 000 people.12

Notably, over 20% of Canada's population is foreign-born, one of the highest among the G20 economies.13 BC is a Canadian province with a population of ∼4.4 million people and is one of the major immigrant-receiving provinces in Canada. In 2011, 28% of BC's population was estimated to be born outside of Canada.14 Immigration patterns to BC have changed over the past 5 decades, with an increase in migrants coming from high TB-incidence countries. In 1965, the major source countries for immigration to BC were Great Britain (34%) and the USA (17%), followed by Italy (6%), Germany (6%) and China (6%).15 In contrast, between the years 2000 and 2015, approximately half of all immigrants to BC came from three high TB-incidence source countries—China (23%), India (15%) and the Philippines (12%).16

In BC, the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) is the centralised public health agency that is responsible for diagnosis and treatment of the majority of active TB and LTBI patients in the province.17 The BCCDC also maintains the Provincial TB Registry which includes diagnostic and treatment data on active TB cases. Mandatory notification by public health partners and routine reporting from the centralised provincial mycobacteriology laboratory and provincial pharmacy makes the Provincial TB Registry virtually complete for active TB.

Data sources and linkages

This study will take advantage of a recently established permanent data linkage between Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and Population Data BC. IRCC is the Canadian Federal Government agency that grants citizenship, facilitates the arrival of immigrants, provides protection to refugees and offers assistance for migrants to Canada.18 IRCC data on Permanent Residents have been provided to Population Data BC by the IRCC Research and Evaluation Branch for the purpose of facilitating immigrant health-related research projects. De-identified data pertaining to citizenship and immigration, such as immigration class, year of arrival and country of origin, are available to researchers by request.19

Population Data BC is a multiuniversity data resource housed at the University of BC. Population Data BC supports research access to individual-level, de-identified longitudinal data on BC residents. Population Data BC holdings represent one of the world's largest collections of administrative data, including healthcare, health services and population health data.20 These data sets are all linkable to each other and to additional external data sets, where approved by the data provider.

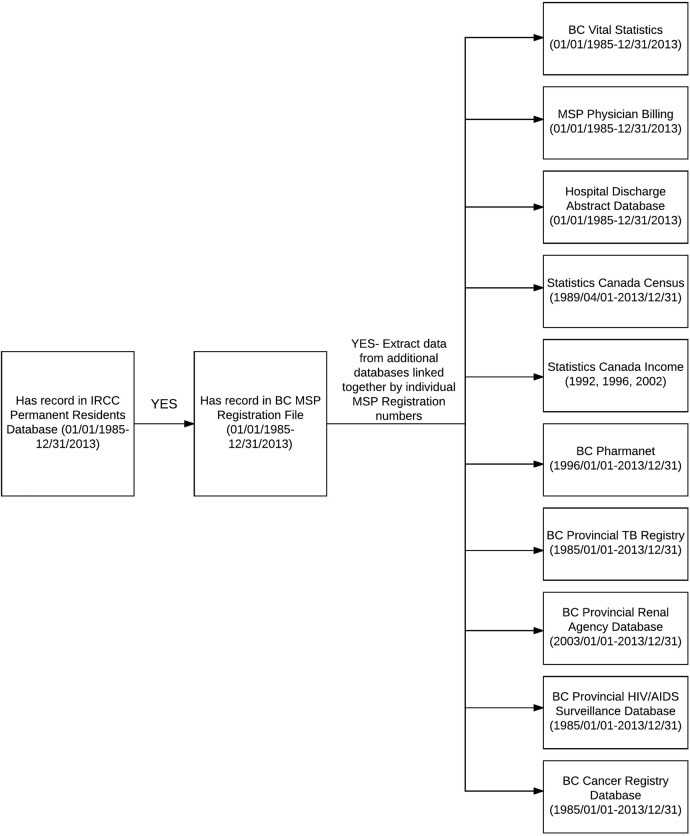

The IRCC database has been linked previously with Population Data BC using a minimum 6 of a 7-point matching algorithm (First Name, Middle Name, Surname, Sex, Year of Birth, Month of Birth, Day of Birth) (Personal communication from Population Data BC, 21 October 2015). From this linked data set, we requested data on all foreign-born permanent residents who established residency in BC between 1985 and 2013. The requested data include data on physician billings, hospitalisations, drugs dispensed from community pharmacies, vital statistics, HIV testing, cancer diagnoses, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and dialysis treatment, and all TB and LTBI testing and treatment data in BC. Data will be linked between each data source using unique scrambled patient identification numbers (table 1; figure 1).

Table 1.

Databases requested in data linkage

| Databases | Description | Date range requested |

|---|---|---|

| 1. IRCC Database21 | Demographic and immigration-related data for all permanent residents to Canada | 1985/04/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 2. BC Vital Statistics22 | Deaths recorded in BC | 1985/04/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 3. BC MSP Registration23 | Dates of registration in the BC MSP | 1985/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 4. BC MSP Physician Billing24 | Outpatient and inpatient physician fee-for-services billing records, as paid by MSP. Includes ICD-9 diagnostic codes (available since 1991/92) and MSP-specific fee-item codes | 1985/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 5. Hospital Discharge Abstracts (DAD)25 | BC hospital discharge records (inpatient and day surgeries). Includes up to 20 ICD diagnostic codes and up to 20 procedure codes. Coding systems are ICD-9-CA/CCI (1991/92 to 2000/01) and ICD-10-CA/CCP (from 2001/02 to present) | 1985/04/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 6. Statistics Canada Census26 | Income quintiles, by 3-digit postal code area (note: quintiles data only available beginning in 1994): ‘Neighbourhood income per person equivalent, household income adjusted for household size’ | 1989/04/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 7. Statistics Canada Income Bands27 | 1000 income bands per year, based on ranking of Revenue Canada's tax filer data of average equalised income per postal code | 1992, 1996, 2002 |

| 8. BC PharmaNet28 | All drugs dispensed from BC community pharmacies (including drugs paid by MSP and private insurers; excluding inpatient drugs in acute care hospitals) | 1996/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 9. BC Provincial TB Registry (BCCDC-iPHIS)29 | Active TB and LTBI diagnostics and treatment in BC30 | 1985/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 10. BC Provincial Renal Agency Database (PROMIS)31 | All chronic kidney disease clinic visits (after first referral to nephrologist), inpatient/outpatient dialysis visits and transplant registration, collected through BC renal clinics and transplant programmes32 33 | 2003/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 11. BC Provincial HIV/AIDS Surveillance Database (BCCDC-HAISIS)34 | All individuals with a positive HIV test done in BC, or reported to the BCCDC. Includes BCCDC confirmatory laboratory testing for HIV antibodies (>95% of all screening tests for HIV in the province), IRCC reporting of HIV-positive status detected through immigration screening medical exams and passive clinician reporting of AIDS cases. Note: mandatory reporting of HIV test-positive status began in 200335 | 1985/01/01 to 2013/12/31 |

| 12. BC Cancer Agency Registry36 | All primary cancers diagnosed in BC residents (obtained from multiple sources, including pathology, cytology, other labs, death certificates and admissions to BC cancer centres)37 | 1985/04/01 to 2013/12/31 |

BC, British Columbia; BCCDC, BC Centre for Disease Control; CCI, Canadian Classification of Interventions; CCP, Canadian Classification of Procedures; DAD, hospital discharge abstract database; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IRCC, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; MSP=Medical Services Plan.

Figure 1.

Schematic of database linkages.

Study design and study population

This is a retrospective population-based cohort study. The study population will include all foreign-born permanent residents who have landed in Canada between 1 January 1985 and 31 December 2013, and established residency in BC at any point during this same period.

Individuals will be identified as being resident in BC when they have registered in the provincial Medical Services Plan (MSP).38 We will exclude individuals from our cohort who did not acquire an MSP number. MSP is the Universal Health Insurance Programme administered by the provincial government of BC. It insures medically required services provided by physicians and healthcare practitioners. Enrolment with MSP is mandatory for all eligible BC residents and their dependents. To be eligible, residents must be citizens or permanent residents of Canada and must be physically present in BC at least 6 months in a calendar year. Depending on an individual's income, MSP coverage may be free, or may require monthly premiums up to $C75 per month. Thus, MSP coverage can be considered a good proxy measure for residence in BC.

Measuring follow-up time and primary outcome

The primary outcome measure will be time to active TB diagnosis. TB diagnosis will be identified based on BCCDC TB Registry data, and will include all TB sites (ie, pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB), either microbiologically or clinically confirmed. A TB diagnosis is established in the BCCDC registry based on the Canadian TB Reporting System Guidelines.39

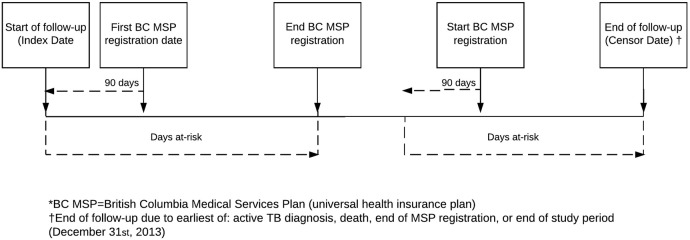

Calculation of follow-up time will begin for all individuals at their index event (figure 2). The index event will be identified as occurring 90 days before their first MSP registration date. We will use the MSP registration as a proxy to ensure that individuals are resident in BC. We will start the collection of follow-up time at 90 days before first MSP registration, to account for the mandatory 90-day waiting period for starting MSP. For example, an individual who moved to BC from overseas and came under MSP coverage on 1 March would be treated in our study as having been a BC resident since January 1st of the same year. Their exposure and time at risk for study outcomes would then be treated as beginning on 1 January. This will allow us to capture TB outcomes occurring within the first 3 months of residency in the province, while an individual is still awaiting registration in MSP. Follow-up will be censored at active TB diagnosis, or after the end of MSP coverage, death or end of the study period (31 December 2013).

Figure 2.

Defining study follow-up periods—index date (entry into cohort) and breaks in MSP registration. †End of follow-up due to earliest of: active TB diagnosis, death, end of MSP registration, or end of study period (31 December 2013). BC MSP, British Columbia Medical Services Plan (universal health insurance plan).

Potential risk factors for active TB

We will identify risk factors targeted in the Canadian TB Standards as high-risk conditions for TB development or TB reactivation.7 See online supplementary appendix (tables 1, 2) for detailed definitions of variables.

bmjopen-2016-013488supp_appendices.pdf (161.5KB, pdf)

Demographic and immigration-related factors will be identified primarily from IRCC records. Variables will include sex, age at arrival to Canada (in years), age at TB diagnosis or censoring (in years), years since arrival in Canada, year of arrival in Canada, immigration classification (ie, economic, refugee or other) and TB incidence in country of origin in year of arrival to Canada.

TB-related risk factors will be identified primarily using data from the Provincial TB Registry, supplemented by data extracted from the literature:

For the TB incidence rate in the individual's country of origin, we will use country-level WHO TB incidence data (all forms of TB/100 000 population), as reported to the WHO for each country per year since 1990.40 For years prior to 1990 (1985–1989), we will apply 1990 TB incidence rates. We will investigate the impact of any changes in WHO definitions of confirmed active TB cases occurring over this time period, and account for this (ie, through the use of weights), if necessary.

BCG vaccination will be verified if the individual has a BCG-positive status recorded in the TB Registry. For individuals without records in the Provincial TB Registry, we will use the World BCG Atlas to identify if an individual likely was previously vaccinated with BCG, based on the reported BCG vaccination policies in their birth country and year of birth.41

Using linked BCCDC TB Registry data, we will identify if an individual was a contact of an active TB case in BC, if they presented with an abnormal chest X-ray, and any dates of positive tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or positive Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) if measured. We will identify if the individual was referred by IRCC for postlanding TB surveillance (ie, IRCC requires immigrants and refugees with chest X-ray or historical evidence of prior TB, when detected in the Prearrival TB Screening Programme, to report to local public health authorities within 30 days of arrival for examination and follow-up).7 42

Finally, we will identify if and when an individual initiated and/or completed LTBI treatment. LTBI treatment completion will be defined as being dispensed at least 80% of recommended doses (ie, completion of 210 doses of isoniazid or 76 doses of rifampin, based on recommended guidelines).7

Medical comorbidities considered high-risk for the development of active TB and which have been targeted for LTBI screening by the Canadian TB Standards will be identified.7 These include HIV/AIDS, CKD, cancer, diabetes, medical immunosuppression, solid organ transplant and silicosis (See online supplementary appendices tables 1 and 2). Disease registries will be used as the gold standard for disease diagnoses, where available. We will supplement disease registry data with data from health administrative databases, using validated algorithms where possible. For the purposes of estimating the impact of medical comorbidities on TB risk, we will estimate risk factor exposure start and end dates separately for each disease based on expert opinion and literature review (see online supplementary appendix table 1). For example, for the impact of drugs on TB risk, we will allow a 30-day lag period for a drug to take effect. For chronic diseases such as diabetes, we will assume that the effect on TB risk begins 90 days before the first date where we have confirmation of diabetes diagnosis to allow for a period of diagnostic delay.

As the Provincial Renal Agency data for CKD and solid organ transplants are not available prior to 2003, we will develop MSP physician billing/hospitalisation-based data algorithms and compare these against patient registry data between the years 2003 and 2013. Algorithms based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic codes, and inpatient and outpatient procedure codes, with the highest accuracy for identifying CKD and solid organ transplants will be identified, and their reliability as indicators will be described.

Analysis plan for each objective

Objective 1: To identify individual risk factors, we will examine the relationship between each potential baseline risk factor and the diagnosis of active TB using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test for categorical risk factors and for some numeric risk factors that naturally split into clinically relevant categories. For other numeric risk factors we will use proportional hazards regression, possibly with regression splines.

Objective 2: To create a predictive model for the risk of developing active TB, we will first randomly partition our complete cohort into three analysis sets with a 2:1:1 ratio. These will be referred to as our training set (50%), validation set (25%) and test set (25%). For the primary predictive models, we will use an extended proportional hazards regression model43 which may include time-varying coefficients, time-varying predictors as well as terms for interactions among the predictors. Our candidate predictive models will be developed based on modern modelling strategies (eg, the lasso) using only the training set. We will then compare the optimism-corrected estimates of performance of our candidate models (ie, c-index measuring concordance between predictions and actual survival) in the validation set. We will choose our final models based on performance and the clinical relevance of their predictors. We will then assess the true generalisation error of our final model44 in the test set. We will also summarise the final model's ability to predict survival at 1 year, 2 years and 5 years using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Other regression models may also be considered in sensitivity analyses (ie, logistic regression models for the development of TB by time points).

We will also perform a descriptive analysis of the medical and demographic variables of interest in the complete data set. TB incidence will be calculated for all demographic and medical risk factors with corresponding 95% CIs.

Statistical analyses will be performed using R (V.3.2.5) and SAS/STAT (V.9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, USA). In general, missing and incomplete data will be excluded from analyses and the number of observations omitted from analyses due to missing data will be documented. When imputation is used, the method and extent will be reported. Observed p values of <0.05 will be described as statistically significant and 95% CIs will be provided for relevant parameter estimates. No corrections will be made for multiple inferences in this predictive modelling analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

We plan to submit our findings for publication in relevant peer-reviewed journals, and aim to create an online TB risk score calculator based on our study findings.

Discussion

The large population of people who could qualify for LTBI screening is a critical barrier to TB elimination efforts in low-incidence regions. By describing how TB risk varies among individuals with multiple interacting risk factors, this study will ensure that scale-up of LTBI screening and therapy will be high yield and have an impact as a public health intervention. Data from this study will also provide opportunity to perform several new analyses that will describe the dynamics of TB disease risk in the foreign-born population of BC. The results of this study can be used to directly inform policy and practice here in BC, but can also be used to inform TB screening in other low TB-incidence regions looking to address TB elimination.

We recognise several potential limitations of this cohort study. First, the IRCC database includes only individuals that received permanent landing status in Canada. Therefore, this study will exclude temporary visitors and workers, some refugee applicants and undocumented migrants. As well, we are limiting our data sets to only those individuals who are registered in the BC MSP as a proxy for residency. It is possible that some residents of BC may not register with MSP and that lapsed MSP coverage may not be a good proxy for leaving the province. Thus, we may also incorrectly estimate person-time of the risk set. We further cannot identify if an individual travels back and forth from high TB-burden settings, which has been shown to increase TB risk.45 We can investigate the impact of breaks in MSP registration through sensitivity analysis; however, we cannot determine whether an individual has travelled to a high TB-burden setting during this period.

As well, as is typical with health administrative database studies, inaccurate classification into risk, exposure or outcome groups due to inaccurate health administrative data is also possible (ie, these data are not collected for research purposes). For example, the use of health administrative data to identify comorbidities and outcomes obviously requires contact with the healthcare system, assumes that diagnoses are accurately coded in billing data and cannot account for inpatient drug treatment data (which are not available). Also, outpatient prescription data will not be available from 1985 to 1995, and data from the Provincial Renal Programme will not be routinely available prior to 2003. Antiretroviral drug dispensation data from the BC Centre of Excellence in HIV/AIDS are also not available, accounting for most outpatient antiretroviral drugs dispensed in the province. Therefore, we can identify when an individual is HIV-infected, but we cannot determine level of immunesuppression.

The major strength of this study is that this cohort represents near-complete capture of the demographic, immigration and healthcare service usage for more than 1 million people over a 28-year period. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the largest cohort assembled to investigate individual comorbidities, exposures and TB outcomes. This large sample size permits us to estimate the effects of combination of demographic and medical risk factors, not just individual risk factors in isolation. Given the study's long duration and the wide diversity of migrants to BC over the past 3 decades, we believe the results will help inform screening in other low TB-incidence regions with similar patterns of migration, including elsewhere in Canada, the USA, Australia, New Zealand, the UK and Western Europe.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Maureen Mayhew for feedback on study design and Dr Kevin Schwartzman for feedback on our initial draft protocol. We thank Leslie Chiang for assistance with literature review.

Footnotes

Contributors: JCJ and LAR are the primary study investigators. JCJ initiated the project and led on the design of the grant. JCJ and LAR led on the development of the protocol. JRC, RFB, DZR, KR, VJC and FM are investigators on the project who shared in the development of the protocol. All authors provided important intellectual content and gave their final approval of the version submitted for publication.

Funding: This work is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. It is led by the BC Centre for Disease Control and the University of British Columbia. The partners in research are Population Data BC, BC PharmaNet, BC Cancer Agency and BC Renal Agency.

Disclaimer: All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this protocol are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Steward(s).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Review Board (H13-03216).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: These data are held by Population Data BC, housed at the University of British Columbia. All data to be used in this study are available to researchers through a data access request to Population Data BC.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JR, Chen W, Johnston J et al. . Latent tuberculosis infection screening in immigrants to low-incidence countries: a meta-analysis. Mol Diagn Ther 2015;19:107–17. 10.1007/s40291-015-0135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell J, Marra F, Cook V et al. . Screening immigrants for latent tuberculosis: do we have the resources? CMAJ 2014;186:246–7. 10.1503/cmaj.131025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pareek M, Watson JP, Ormerod LP et al. . Screening of immigrants in the UK for imported latent tuberculosis: a multicentre cohort study and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:435–44. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70069-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pareek M, Bond M, Shorey J et al. . Community-based evaluation of immigrant tuberculosis screening using interferon γ release assays and tuberculin skin testing: observational study and economic analysis. Thorax 2013;68:230–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ et al. . Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016;316:962–9. 10.1001/jama.2016.11046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 7th Edition 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tbpc-latb/pubs/tb-canada-7/index-eng.php (accessed 21 Apr 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B et al. . Tuberculosis: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. Can Med Assoc J 2011;183:E939–51. 10.1503/cmaj.090302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan K, Hirji MM, Miniota J et al. . Domestic impact of tuberculosis screening among new immigrants to Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2015;187:E473–81. 10.1503/cmaj.150011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langlois-Klassen D, Wooldrage KM, Manfreda J et al. . Piecing the puzzle together: foreign-born tuberculosis in an immigrant-receiving country. Eur Respir J 2011;38:895–902. 10.1183/09031936.00196610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FitzGerald JM, Fanning A, Hoepnner V et al. , Group CME of TS. The molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in western Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:132–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health Agency of Canada. Tuberculosis in Canada 2014—Pre-release 2016. http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/diseases-conditions-maladies-affections/tuberculosis-2014-tuberculose/index-eng.php (accessed 19 Apr 2016).

- 13.Organization for Economic Development . Foreign-Born Population (indicator) 2016. https://data.oecd.org/migration/foreign-born-population.htm (accessed 17 May 2016).

- 14.Statistics Canada. NHS Focus on Geography Series: British Columbia 2015. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Pages/FOG.cfm?lang=E&level=2&GeoCode=59 (accessed 6 Jun 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Immigration Statistics Canada. http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/202/301/immigration_statistics-ef/index.html (accessed 26 Sep 2016).

- 16.Permanent Resident Admissions. http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/ad975a26-df23-456a-8ada-756191a23695 (accessed 26 Sep 2016).

- 17.BCCDC. Annual Summary of Reportable Diseases 2014. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/Epid/Annual%20Reports/AR2014FinalSmall.pdf (accessed 19 Apr 2016).

- 18.Citizenship and Immigration Canada. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/ (accessed 20 Apr 2016).

- 19.Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) Permanent Residents Data. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/internal/demographic/CICpermres (accessed 20 Apr 2016).

- 20.Population Data BC https://www.popdata.bc.ca/ (accessed 20 Apr 2016).

- 21. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [creator] (2014): Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. CIC (2015). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 22. BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] (2015): BC Vital Statistics. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BC Vital Statics Agency (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 23. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2015): Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 24. British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2015): Medical Service Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 25. Canadian Institute for Health Information [creator] (2015): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 26. Statistics Canada [creator] (2015): Statistics Canada Census. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. StatsCanada (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 27. Statistics Canada [creator] (2015): Statistics Canada Income Bands. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. StatsCanada (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 28. BC Ministry of Health [creator] (2015): PharmaNet. BC Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. Data Stewardship Committee (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 29. BC Centre for Disease Control [creator] (2015): BC Provincial TB Registry (BCCDC-iPHIS). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BCCDC (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 30.BC Centre for Disease Control. TB in British Columbia: Annual Surveillance Report 2012–2013. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/TB/TB_Annual_Report_2012-2013.pdf (accessed 30-May-2016).

- 31. BC Renal Agency [creator] (2015): BC Provincial Renal Agency Database (PROMIS). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. PROMIS(2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 32.BC Provincial Renal Agency. Newsletter, November 2015. http://www.phsa.ca/our-services-site/Documents/BC%20Renal%202015.pdf (accessed 30 May 2016).

- 33.BC Provincial Renal Agency. BC Promis Database. http://www.bcrenalagency.ca/health-professionals/professional-resources/promis-database (accessed 30 May 2016).

- 34. BC Centre for Disease Control [creator] (2015): BC Provincial HIV/AIDS Surveillance Database (BCCDC-HAISIS). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BCCDC (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 35.BC Centre for Disease Control. HIV in BC Annual Surveillance Report 2014 2015. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/STI/HIV_Annual_Report_2014-FINAL.pdf (accessed 30 May 2016).

- 36. BC Cancer Agency Registry Data [creator] (2015): Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BC Cancer Agency (2014). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 37.BC Cancer Agency. BC Cancer Registry. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/professional-resources/bc-cancer-registry (accessed 30 May 2016).

- 38.Government of BC. Medical Services Plan (MSP). http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/health-drug-coverage/msp/bc-residents (accessed 22 Apr 2016).

- 39.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Tuberculosis Reporting System: Reporting Form Completion Guidelines, Version 1.9 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tbpc-latb/pdf/guidelinesform-eng.pdf (accessed 20 May 2016).

- 40.WHO World TB Database. http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/download/en/ (accessed 22 Apr 2016).

- 41.The BCG World Atlas: A Database of Global BCG Vaccination Policies and Practices. http://www.bcgatlas.org/ (accessed 22 Apr 2016).

- 42.Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Medical Surveillance Handout: Inactive Tuberculosis or other Complex Non-Infectious Tuberculosis. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/tools/medic/physicians/documents/PDF/english.pdf (accessed 22 Apr 2016).

- 43.Therneau T, Grambsch P. Modeling survival data: extending the cox model. New York; Springer-Verlag, 2000:350 p. (Statistics for Biology and Health). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. Springer-Verlag, 2009. (Springer Series in Statistics). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kik SV, Mensen M, Beltman M et al. . Risk of travelling to the country of origin for tuberculosis among immigrants living in a low-incidence country. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013488supp_appendices.pdf (161.5KB, pdf)