Abstract

Objectives

To investigate an association between ideal cardiovascular health metrics (CVH) and the risk of developing end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Setting

Community of Kailuan in Tangshan/China.

Participants

We examined in a community-based longitudinal cohort study 91 443 participants without history of stroke or myocardial infarction at baseline in 2006–2007, with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ≥15 mL/min at baseline, and who participated in at least 1 of 3 follow-up examinations in 2008–2009, 2010–2011 and 2012–2013.

Interventions

CVH was measured by 7 key health factors (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, healthy dietary score, total cholesterol blood concentration, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose) each of which ranged between ‘ideal’ (2) and ‘poor’ (0). With a maximal CVH score of 14, the study participants were divided into categories of <5, 5–9 and 10–14 points.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

CHV, incidence of ESRD.

Results

Incidence of ESRD ranged from 7.06‰ in the lowest CVH category to 2.34‰ in the highest CVH category. After adjusting for age, sex, educational level, income, alcohol consumption and GFR, the lowest CVH category as compared with the highest CVH category had a significantly higher risk of incident ESRD (adjusted HR 2.87; 95% CI 1.53 to 5.39). For every decrease in group number of the cum-CVH score, the risk of ESRD increased by 20% (HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.28). The effect was consistent across sex and all age groups.

Conclusions

A low CVH score significantly increased the risk of incident ESRD. Risk factors for cardiovascular events may also be associated with an increased risk for kidney failure.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Kidney, Cardiovascular health score, End-stage renal disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study investigated the relationship between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and incident end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in a large community-based population, taking into account all parameters of the ideal cardiovascular health metrics.

As potential limitations, each cardiovascular health metric parameter had equal weight in calculating the cardiovascular health score, potentially leading to an oversimplification of the relationship between cardiovascular health score and ESRD.

The self-reported data on salt intake was taken as surrogate of healthy diet.

Individuals without creatinine measurements were excluded from the study that may potentially lead to a bias in the selection of study participants.

The study population was recruited based on a community basis and not on a population basis.

In 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) set a goal to improve the cardiovascular health of Americans by 20% until 2020. To quantify the cardiovascular health and to measure the progress towards reaching the goal, the AHA defined seven health metrics variables (smoking status, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, healthy dietary score, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose) and created three stages for each variable to reflect poor, intermediate and ideal health status for that parameter.1 Subsequent studies revealed that ideal cardiovascular health metrics was protective against asymptomatic intracranial artery stenosis,2 3 cognitive impairment,4 cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related mortality,5–7 and all-cause mortality and cancer.8–10 To cite an example, a previous investigation of the Kailuan study revealed that better cardiovascular health was associated with a lower incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke, with the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke decreasing by about 16% for each unit increase in the cardiovascular health metrics.11

The global incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has markedly increased in the past few years.12 13 Studies have revealed that diabetes mellitus,14 arterial hypertension,15 hypercholesterinaemia,16 higher BMI17 and cigarette smoking were risk factors for ESRD,18 while ESRD increased the mortality of CVDs by a factor of 10–20.19 In a parallel manner, a recent study by Gansevoort et al20 showed that the risk of CVD mortality increased linearly among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). While many studies investigated the association between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and the risk of cardiovascular events, fewer studies have explored so far the association between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and kidney disease. Rebholz and colleagues estimated the association between the seven AHA health metric variables (also called ‘Life's Simple 7’) and incident CKD in almost 15 000 participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study over a median follow-up of 22 years. The health metric factors of smoking, BMI, physical activity, blood pressure and blood glucose were significantly (all p<0.01) correlated with an increased risk for CKD while the health metric factor of diet and blood cholesterol were not related with the risk for CKD in that study population.21 The risk for CKD was negatively associated with the number of ideal health factors. Also other studies investigated an association between cardiovascular risk factors and incident kidney disease, such as the investigations by Bash et al,22 by Ricardo et al,23 by Hui et al24 and by Hsu et al.25 The main outcome parameter of our study, the development of ESRD was addressed in a previous study by Muntner and associates who had not included all AHA health metric factors.26 In their prospective cohort study consisting of 3093 patients with ESRD, patients with four ideal cardiovascular health metrics had a significantly lower risk to develop ESRD after a follow-up of 4 years as compared with individuals with one ideal cardiovascular health metric.26 After adjusting for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) however, the association was no longer significant. Since most of the previous studies addressed associations between the cardiovascular health factors and incident CKD and did not specifically focus on incident ESRD and since the available studies on incident ESRD either did not include all seven health factors or had variable results, we conducted the present investigation to extend the observations made in previous studies and to include all cardiovascular health metric factors into a multivariate analysis in a relatively large study population.

Methods

The Kailuan study (registration number: ChiCTR-TNC-1100148) is a prospective community-based cohort study conducted in the community of Kailuan in the industrial city of Tangshan (Hebei Province).11 27 A written informed consent was signed by all participants. The Kailuan study included employees and retirees of the Kailuan Group Company which is a coal mine industry in Tangshan. Between June 2006 and October 2007, 101 510 individuals (81 110 men) with an age between 18 and 98 years were examined at baseline of the study in 2006/2007 and they were re-examined in 2-year intervals during the periods of 2008–2009, 2010–2011 and 2012–2013. The present investigation included those individuals who had not been diagnosed with ESRD at the baseline examination, for whom complete data of their cardiovascular health metrics obtained at the baseline examination were available, and who had participated in at least one of the three follow-up examinations. Individuals with previous stroke or myocardial infarction which had occurred prior to the baseline examination were excluded from the study to prevent a potential influence of these major diseases on the prospectively assessed outcome parameter of incident ESRD. Patients with acute kidney disease or patients with previous acute kidney disease but then in recovery were also excluded, since the goal of the study was to assess the incidence of chronic end-stage disease of the kidneys.

At the time when examinations were performed at baseline and in the follow-up examinations, an interview with a standardised questionnaire was carried out including questions on smoking, physical activity and salt intake. The smoking status was classified as ‘never’, ‘former’ or ‘current’. Never smoking was defined as the ideal healthy behaviour (with respect to smoking), former smoking as intermediate healthy behaviour and current smoking as poor healthy behaviour. With respect to physical activity, ideal healthy behaviour, intermediate healthy behaviour and poor healthy behaviour were defined as ≥80, 1–79 and 0 min of moderate or vigorous activity per week, respectively. Since detailed information on diet (eg, intake of fruits, vegetables or meat) was missing, we used the information on salt intake as a surrogate of information on diet in general. As part of the standardised questionnaire, we asked how much salt the participants used when they prepared their meals. Self-reported salt intake was classified as ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’, without that the amount of salt consumed was measured. ‘Low’ salt intake was defined as the ideal diet behaviour, and medium salt intake and high salt intake were defined as intermediate and poor diet behaviours, respectively. The interview also included questions on demographic and clinical characteristics (age, sex, personal monthly income, level of education and history of diseases, and use of arterial antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol-lowering medication, and glucose-lowering drugs). Based on their age, the study participants were differentiated into two categories of age ≤60 years and of age >60 years. The self-reported average monthly income was categorised as ‘<¥600’, ‘¥600–¥800’ or ‘≥¥800’. The educational attainment was categorised as ‘illiteracy or primary school’, ‘middle school’ and ‘high school or above’.

According to the definitions by the AHA, BMI was classified as ideal (<25 kg/m2), intermediate (25–29.9 kg/m2) or poor (≥30 kg/m2). For the determination of blood pressure, three readings of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were taken at a 5 min interval after the participants had rested in a chair for at least 5 min. The average of three readings was used for data analysis. The blood pressure was graded as ideal (SBP<120 mm Hg and DBP<80 mm Hg and untreated), intermediate (120 mm Hg≤SBP≤139 mm Hg, 80 mm Hg≤DBP≤89 mm Hg, or treated to SBP/DBP<120/80 mm Hg), or poor (SBP≥140 mm Hg, DBP≥90 mm Hg or treated to SBP/DBP>120/80 mm Hg.1

The biochemical analysis of fasting blood samples included determination of the concentrations of glucose, total cholesterol and triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and creatinine. The coefficient of variation in serum creatinine concentration determination was <5%. According to the definitions by the AHA,1 fasting blood glucose was classified as ideal (<5.6 mmol/L and untreated), intermediate (5.6–6.9 mmol/L or treated to <5.6 mmol/L) or poor (≥7.0 mmol/L or treated to ≥5.6 mmol/L); and total cholesterol blood concentration was graded as ideal (<200 mg/dL and untreated), intermediate (200–239 mg/dL or treated to <200 mg/dL) or poor (≥240 mg/dL or treated to ≥200 mg/dL), respectively.

ESRD was defined as an eGFR of <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or when the participant was on dialysis or had received kidney transplantation.28 The eGFR was estimated by using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.29

Statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (SPSS for Windows, V.22.0, IBM-SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Continuous variables were described as mean±SD and were compared by analysis of variance or by applying the Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical variables were described as percentages and were compared using χ2 tests. Cox regression model was used to estimate the risk of ESRD associated with cardiovascular health metrics. HRs and 95% CIs were calculated. Proportional hazard assumptions were confirmed by testing correlations between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals for ideal cardiovascular health metrics and time. No significant non-proportional effects (p>0.05) were observed. We fitted three multivariate models. Model 1 adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 additionally adjusted for educational level, income level and alcohol consumption. Model 3 further adjusted for GFR. Since there were 11 hospitals responsible for laboratory tests in this study, we used a random effect for each hospital to account for the potential measurement bias. The interactions of cardiovascular health with gender and age on the risk of ESRD were analysed by multivariate Cox regression modelling. All statistical tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at p<0.05.

Results

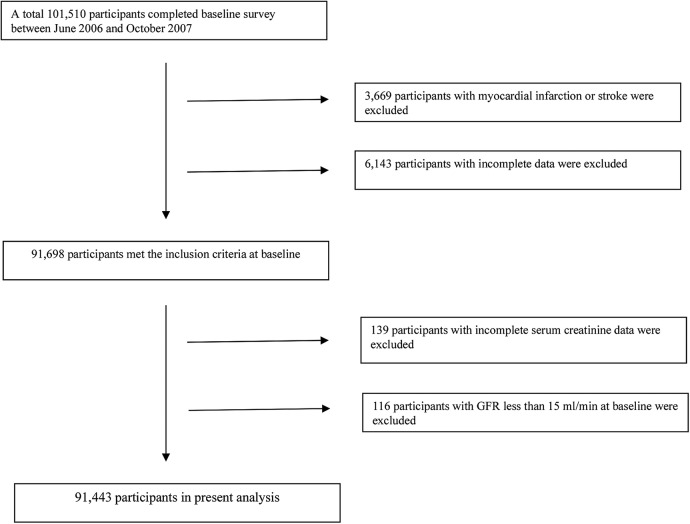

Out of the 101 510 individuals participating in the baseline examination, 3669 participants were excluded due to a history of stroke or myocardial infarction which had occurred prior to the baseline examination; 6282 individuals were excluded because of incomplete cardiovascular health metrics data or incomplete serum creatinine data; and 116 persons were excluded due to a eGFR of <15 mL/min at baseline. The remaining 91 443 participants (20.5% women) were included into the present study (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study participants. GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Comparing the baseline characteristics between the three groups of study participants revealed that a higher cardiovascular health-defined group was significantly (p<0.001) associated with higher level of education, lower proportion of men, higher income, less alcohol consumption and a lower high-sensitive C reactive protein concentration (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to the cardiovascular health score (n=91 443)

| Cardiovascular health scores | Total (n=91 443) | 10–14 (n=35 810) | 5–9 (n=53 815) | 0–4 (n=1818) | p Value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.5±12.4 | 49.8±13.4 | 52.7±11.6 | 51.6±9.7 | <0.001 |

| Men, n(%) | 72 713 (79.4) | 23 932 (66.8) | 47 014 (87.2) | 1767 (96.5) | <0.001 |

| C reactive protein | 0.79 (0.30, 2.00) | 0.60 (0.22, 1.70) | 0.89 (0.34, 2.19) | 1.21 (0.54, 2.72) | <0.001 |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Illiteracy | 1079 (1.2) | 333 (0.9) | 715 (1.3) | 31 (1.7) | |

| Elementary school | 8231 (9.0) | 2304 (6.4) | 5633 (10.5) | 294 (16.2) | |

| High school | 75 745 (82.8) | 29 549 (82.5) | 44 776 (83.2) | 1420 (78.1) | |

| College or above | 6388 (7.0) | 3624 (10.1) | 2691 (5.0) | 73 (4.0) | |

| Income RMB/month, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <800 | 78 455 (85.8) | 30 694 (85.7) | 46 240 (85.9) | 1521 (83.7) | |

| 800–1000 | 6920 (7.6) | 2544 (7.1) | 4213 (7.8) | 163 (9.0) | |

| >1000 | 6068 (6.6) | 2572 (7.2) | 3362 (6.2) | 134 (7.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 54 182 (59.2) | 26 443 (73.8) | 27 258 (50.7) | 429 (23.4) | |

| Past | 3127 (3.4) | 789 (2.2) | 2235 (4.2) | 103 (5.7) | |

| Current, <1 times/day | 17 799 (19.5) | 5865 (16.4) | 11 489 (21.3) | 445 (24.5) | |

| Current, 1+ times/day | 16 388 (17.9) | 2713 (7.6) | 12 833 (23.8) | 842 (46.3) |

The incidence of ESRD ranged from 2.34‰ in the highest cardiovascular health category to 7.06‰ in the lowest cardiovascular health category (table 2). Compared with the participants in the highest cardiovascular health category (10–14 points), after adjustment for age, sex, education level, income level, alcohol consumption and eGFR at baseline examination, those in the lowest cardiovascular health category (0–4 points) had a significantly increased risk of ESRD (adjusted HR 2.87; 95% CI 1.53 to 5.39). For every decrease in the group number of the cardiovascular health score, the risk of ESRD increased by ∼20% (HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.28) (table 2). The effect was consistent across sex and all age groups below the age of 60 years (table 3). Significant associations were found both for men (p trend<0.001) and for women (p trend=0.017), but only in participants with an age of <60 years (p trend<0.001), not in those with age >60 years (p trend=0.105). There were significant interactions between the cardiovascular health score and age (p interaction <0.001) and sex (p interaction<0.001), respectively.

Table 2.

HRs (95% CIs) of end-stage renal disease stratified by the cardiovascular health score at baseline

| Cardiovascular health score at baseline | 10–14 (n=35 810) | 5–9 (n=53 815) | 0–4 (n=1818) | One score decrease (n=91 443 ) | p Value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 77 (0.22) | 184 (0.34) | 12 (0.66) | 273 (0.30) | |

| Cumulative incidence/1000 | 2.34 | 3.87 | 7.06 | 3.35 | |

| Model 1* | 1 | 1.66 (1.26 to 2.19) | 3.29 (1.78 to 6.10) | 1.21 (1.14 to 1.29) | <0.001 |

| Model 2† | 1 | 1.72 (1.30 to 2.27) | 3.62 (1.93 to 6.79) | 1.24 (1.16 to 1.32) | <0.001 |

| Model 3‡ | 1 | 1.55 (1.17 to 2.04) | 2.87 (1.53 to 5.39) | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.28) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for age (years) and sex.

†Adjusted for as model 1 plus education level (elementary school, high school, college or above), income level (income >800 RMB/month, income ≤800 RMB/month), alcohol consumption (never, past, current, <1 times/day or current, 1+ times/day) and C reactive protein blood concentration (quartile).

‡Adjusted for as model 2 plus estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 3.

Incidence and HRs (95% CIs) of end-stage renal disease in different subgroups according to the baseline cardiovascular health score

| 10–14 (n=35 810) | 5–9 (n=53 815) | 0–4 (n=1818) | One score decrease (n=91 443) | p Value for trend | p Interaction* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 30 (0.43) 7.25 1.25 (0.71 to 2.20) |

<0.001 | |||||

| Women, case number | 29 (0.24) | 59 (0.31) | |||||

| Cumulative incidence/1000 | 2.60 | 3.34 | |||||

| HR‡ | 1 | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.39) | 0.017 | ||||

| Men, case number | 48 (0.20) | 155(0.33) | 11 (0.63) | 214 (0.29) | |||

| Cumulative incidence/1000 | 2.20 | 3.79 | 6.75 | 3.34 | |||

| HR‡ | 1 | 1.59 (1.15 to 2.22) | 2.90 (1.48 to 5.69) | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.29) | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 2.20 | 3.79 | 6.75 | 3.34 | <0.001 | ||

| ≤60 years, case number | 62 (0.21) | 150 (0.36) | 11 (0.71) | 223 (0.31) | |||

| Cumulative incidence/1000 | 2.35 | 4.12 | 7.70 | 3.51 | |||

| HR‡ | 1 | 1.50 (1.10 to 2.05) | 2.79 (1.43 to 5.46) | 1.19 (1.11 to 1.28) | <0.001 | ||

| >60 years, case number | 15 (0.22) | 35 (0.28) | 50(0.26) | ||||

| Cumulative incidence/1000 | 2.28 | 3.84 | 2.82 | ||||

| HR‡ | 1 | 1.56 (0.90 to 2.72) | 1.14 (0.71 to 1.87) | 0.11 | |||

*p Value for interaction between studied factors and exposure status.

‡Adjusted for age (years), sex, education level (elementary school, high school or college or above), income level (income >800 RMB/month, income ≤800 RMB/month), alcohol consumption (never, past, current, <1 times/day or current, 1+ times/d), C reactive protein blood concentration (quartile 1) and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

To examine the influence of any single cardiovascular health metrics on the association between cardiovascular health and incident ESRD, a sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding step-by-step each of the seven metrics from the cardiovascular health score. The association remained to be statistically significant following the exclusion of the individual risk factors, except for excluding the parameters of cholesterol and fasting blood glucose in women (table 4).

Table 4.

HRs (95% CIs) of end-stage renal disease according to the baseline cardiovascular health score with one of its components removed

| Total |

Women |

Men |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removed component | HR (95% CI) for one score decrease | p Value for trend | HR (95% CI) for one score decrease | p Value for trend | HR (95% CI) for one score decrease | p Value for trend |

| Smoking* | 1.21 (1.13 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.41) | 0.008 | 1.20 (1.11 to 1.30) | <0.001 |

| Salt intake* | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.43) | 0.007 | 1.20 (1.11 to 1.29) | <0.001 |

| Physical exercise* | 1.21 (1.14 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.02 to 1.37) | 0.030 | 1.22 (1.13 to 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol* | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.14 (0.97 to 1.35) | 0.121 | 1.26 (1.16 to 1.36) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure* | 1.18 (1.10 to 1.27) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.43) | 0.034 | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | <0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose* | 1.15 (1.07 to 1.23) | 0.001 | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.31) | 0.246 | 1.15 (1.06 to 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index* | 1.28 (1.19 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.14 to 1.59) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.37) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for age (years), sex, education level (elementary school, high school, college or above), income level (income >800 RMB/month, income ≤800 RMB/month), drinking (never, past, current, <1 times/day or current, 1+ times/d), C reactive protein (quartile) and glomerular filtration rate.

Discussion

In the present study, we found an association between worse cardiovascular health metrics and elevated risks of developing ESRD, independently of age, sex, family income, alcohol consumption and eGFR at baseline of the study. Our findings revealed that ideal cardiovascular health as measured by the seven health metrics parameters was protective against incident ESRD. Removal of any one of the seven parameters of the cardiovascular health metrics, except for the parameters of blood cholesterol concentration and fasting blood glucose concentration in women, did not change the significance of the association between cardiovascular health score and incident ESRD. The subgroup analyses revealed that the association between a low cardiovascular health score and incident ESRD was significant mostly for participants aged <60 years, while in the elder individuals the association was not statistically significant.

The findings of our study agree with the observations made in previous investigations. Perneger et al14 examined 716 newly treated patients with kidney failure aged 20–64 years and 361 age-matched control participants. They found that patients with insulin-dependent diabetes (OR 33.7) and non-insulin-dependent diabetes (OR 7.0) were at greater risk for ESRD than were persons without diabetes. The diagnosis of diabetes in Perneger et al’s study may have as surrogate the blood fasting concentration of glucose in our study. Hsu et al15 retrospectively performed a cohort study among members of a large integrated healthcare provider. Among a total of 316 675 members with an eGFR≥60 mL/min and lack of proteinuria or haematuria, 1149 patients developed ESRD during 8 210 431 person-years of follow-up. Compared with individuals with a blood pressure <120/80 mm Hg, the adjusted relative risks for developing ESRD in the total study population and in various subgroups were 1.62 for blood pressures of 120 to 129/80 to 84 mm Hg, 1.98 for blood pressures of 130 to 139/85 to 89 mm Hg, 2.59 for blood pressures of 140 to 159/90 to 99 mm Hg, 3.86 for blood pressures of 160 to 179/100 to 109 mm Hg, 3.88 for blood pressures of 180 to 209/110 to 119 mm Hg and 4.25 for blood pressures of 210/120 mm Hg or higher. The authors concluded that even relatively modest elevation in blood pressure was an independent risk factor for ESRD. Sundin et al30 examined a cohort of Swedish male residents born between 1952 and 1956 who attended the mandatory military conscription examinations in late adolescence. In the period from 1985 to 2009, ESRD developed in 534 patients as compared with 5127 control individuals. Incident ESRD was strongly associated with arterial hypertension (OR 3.97) for grade 2 hypertension and higher. In a similar manner, higher BMI was correlated with an increased ESRD incidence (OR 3.53). Orland and colleagues found that a Southern dietary pattern rich in processed and fried foods was associated independently with mortality in persons with ESRD, while a diet rich in fruits and vegetables appeared to be protective.31 Haroun et al32 performed a community-based, prospective observational study of 20-year duration to examine the association between hypertension and smoking on the future risk of ESRD in 23 534 men and women. As compared with individuals with optimal blood pressure, they found an adjusted HR of developing ESRD among women of 2.5 for normal blood pressure, 3.0 for high-normal blood pressure, 3.8 for stage 1 arterial hypertension, 6.3 for stage 2 arterial hypertension and 8.8 for stage 3 or 4 of arterial hypertension. Similar results were obtained for men. Also current cigarette smoking was associated with the risk of ESRD (HR in women 2.9; in men 2.4).

The findings obtained in our study extend the observations made in previous investigations by including all parameters which form the cardiovascular health metrics into a multivariate analysis, while the former studies mostly considered only single factors for the development of ESRD. To cite an example, in a prospective cohort study consisting of 3093 patients with ESRD, patients with four ideal cardiovascular health metrics had a significantly lower risk to develop ESRD after a follow-up of 4 years as compared with individuals with one ideal cardiovascular health metric.26 After adjusting for eGFR, the association was no longer significant. In our study, the association between poor cardiovascular health metrics was strongly correlated with incident ESRD also after adjusting for potential confounders including eGFR.

Our study showing an association between poor cardiovascular health metrics and incident ESRD is parallel to other investigations in which a worse cardiovascular health score was correlated with an increased risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancer, and all-cause death.6–10

The reason for the discrepancy between the younger participants in our study, for whom an association between a worse cardiovascular health score and higher incidence of ESRD was found, and the older participants without such a significant relationship may be the higher mortality rate in the elderly individuals who, due to a generally increased morbidity, may not have lived long to develop ESRD.

The importance of the findings obtained in our study is based on each of the seven cardiovascular health metrics parameters with their impact on the development, and presumably, also on the prevention, of ESRD, so that public healthcare measures for the prevention of ESRD should take each one of them into account. This was suggested when we conducted additional analyses removing each ideal health metric at a time. Although the statistical strength of the association between the remaining CVH metric factors and incident ESRD was attenuated after a single factor of the ideal cardiovascular health metrics was removed from the total score, the association remained statistically significant. The results indicated that each of the ideal health metric factors was important.

There are limitations in our study. First, each cardiovascular health metric parameter had equal weight in calculating the cardiovascular health score. It may have oversimplified the relationship between cardiovascular health score and ESRD. Second, we used self-reported information on salt intake as a surrogate of diet without measuring the 24 hours urinary excretion. For a subgroup of the study population, however, we compared the self-reported assessment of salt intake with the measurement of 24 hours urinary excretion and found a significant correlation between both parameters with a regression coefficient of r=0.78. In addition, the main limitation of the Kailuan cohort in that aspect was the lack of sufficient dietary information in general for any meaningful heart-healthy diets analysis, since sodium intake was only one of the components for health diets. Third, participants without creatinine measurements at the first, second or third follow-up examination were excluded from the study. This may have led to a bias in the selection of study participants. Fourth, the Kailuan Industrial Group is dominated by heavy industry, so there were men than women included into the study population. It was however, not the purpose of our study to examine the prevalence of ESRD or other disorders in the Chinese population but to explore associations between cardiovascular health parameters and ESRD. This weakness in the study design may therefore not have markedly influenced the results and conclusions of our study. Fifth, the Kailuan study cohort had a limited sample size with respect to patients with ESRD and the statistical power for a detailed stratified analysis was relatively low. The strength of our study are that it was the first investigation on a relationship between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and incident ESRD in a large community-based population; and that it was the first to assess all parameters of the ideal cardiovascular health metrics and to include them into a multivariate analysis, to reduce the risk of bias due to overlooked confounding parameters.

In conclusion, a low cardiovascular health score significantly increased the risk of incident ESRD. Since factors related to the incidence of a disease may also pathogenically be connected with the development of the disorder, the findings of our study may also be interesting for further elucidating the pathogenesis of CKD and they may additionally be important from a public health point.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLW was involved in design of the study; QLH, SLW, XXL, SSA, YTW, JSG, SHC, XKL, QZ, RYM, XMS were involved in conducting the examinations and statistical analysis; QLH, SLW, XXL, SSA, YTW, JSG, SHC, XKL, QZ, RYM, XMS, JBJ were involved in drafting the manuscript and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Kailuan General Hospital, following the guidelines outlined by the Helsinki Declaration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D et al. . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586–613. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oikonen M, Laitinen TT, Magnussen CG et al. . Ideal cardiovascular health in young adult populations from the United States, Finland, and Australia and its association with CIMT: the international childhood cardiovascular cohort consortium. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000244 10.1161/JAHA.113.000244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Zhang S, Wang C et al. . Ideal cardiovascular health metrics on the prevalence of asymptomatic intracranial artery stenosis: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58923 10.1371/journal.pone.0058923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis JP, Loria CM, Launer LJ et al. . Cardiovascular health through young adulthood and cognitive functioning in midlife. Ann Neurol 2013;73:170–9. 10.1002/ana.23836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong C, Rundek T, Wright CB et al. . Ideal cardiovascular health predicts lower risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death across whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the northern Manhattan study. Circulation 2012;125:2975–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Zhou Y, Gao X et al. . Ideal cardiovascular health metrics and the risks of ischemic and intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:2451–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.678839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA et al. . Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American heart association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1690–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Flanders WD et al. . Trends in cardiovascular health metrics and associations with all-cause and CVD mortality among us adults. JAMA 2012;307:1273–83. 10.1001/jama.2012.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Chi HJ, Cui LF et al. . The ideal cardiovascular health metrics associated inversely with mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular diseases among adults in a northern Chinese industrial city. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e89161 10.1371/journal.pone.0089161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Shay CM, Abramson JG et al. . Ideal cardiovascular health is inversely associated with incident cancer: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation 2013;127:1270–5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu S, Huang Z, Yang X et al. . Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health and its relationship with the 4-year cardiovascular events in a northern Chinese industrial city. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:487–93. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.963694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J et al. . Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives—a position statement from kidney disease improving global outcomes. Kidney Int 2007;72:247–59. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obrador GT, Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Collins AJ et al. . Establishing the Global Kidney Disease Prevention Network (KDPN): a position statement from The National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:361–70. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perneger TV, Brancati FL, Whelton PK et al. . End-stage renal disease attributable to diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:912–18. 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Darbinian J et al. . Elevated blood pressure and risk of end-stage renal disease in subjects without baseline kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:923–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muntner P, Coresh J, Smith JC et al. . Plasma lipids and risk of developing renal dysfunction: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Kidney Int 2000;58:293–301. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer H, Luke A, Bidani A et al. . Obesity and prevalent and incident CKD: the hypertension detection and follow-up program. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:587–94. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elihimas Junior UF, Elihimas HC, Lemos VM et al. . Smoking as risk factor for chronic kidney disease: systematic review. J Brasil Nefrol 2014;36:519–28. 10.5935/0101-2800.20140074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;32:S112–19. 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR et al. . Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 2013;382:339–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rebholz CM, Anderson CA, Grams ME et al. . Relationship of the American Heart Association's Impact Goals (Life's Simple 7) with risk of chronic kidney disease: results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e003192 10.1161/JAHA.116.003192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bash LD, Astor BC, Coresh J. Risk of incident ESRD: a comprehensive look at cardiovascular risk factors and 17 years of follow-up in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:31–41. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricardo AC, Anderson CA, Yang W et al. . Healthy lifestyle and risk of kidney disease progression, atherosclerotic events, and death in CKD: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:412–24. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui X, Matsushita K, Sang Y et al. . CKD and cardiovascular disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: interactions with age, sex, and race. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:691–702. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu CY, Iribarren C, McCulloch CE et al. . Risk factors for end-stage renal disease: 25-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:342–50. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muntner P, Judd SE, Gao L et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors in CKD associate with both ESRD and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;24:1159–65. 10.1681/ASN.2012070642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang A, Liu X, Guo X et al. . Resting heart rate and risk of hypertension: results of the Kailuan cohort study. J Hypertens 2014;32:1600–5. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Kidney F. K/doqi clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:S1–266. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.29865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH et al. . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundin PO, Udumyan R, Sjöström P et al. . Predictors in adolescence of ESRD in middle-aged men. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:723–9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutiérrez OM, Muntner P, Rizk DV et al. . Dietary patterns and risk of death and progression to ESRD in individuals with CKD: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:204–13. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haroun MK, Jaar BG, Hoffman SC et al. . Risk factors for chronic kidney disease: a prospective study of 23,534 men and women in Washington county, Maryland. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2934–41. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000095249.99803.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]