Abstract

Objectives

We compared the effectiveness of diabetes-focused messaging strategies at increasing enrolment in a healthy food programme among adults with diabetes.

Methods

Vitality is a multifaceted wellness benefit available to members of Discovery Health, a South Africa-based health insurer. One of the largest Vitality programmes is HealthyFood (HF), an incentive-based programme designed to encourage healthier diets by providing up to 25% cashback on healthy food purchases. We randomised adults with type 2 diabetes to 1 of 5 arms: (1) control, (2) a diabetes-specific message, (3) a message with a recommendation of HF written from the perspective of a HF member with diabetes, (4) a message containing a physician's recommendation of HF, or (5) the diabetes-specific message from arm 2 paired with an ‘enhanced active choice’(EAC). In an EAC, readers are asked to make an immediate choice (in this case, to enrol or not enrol); the pros and cons associated with the preferred and non-preferred options are highlighted. HF enrolment was assessed 1 month following the first emailed message.

Results

We randomised 3906 members. After excluding those who enrolled in HF or departed from the Vitality programme before the first intervention email, 3665 (94%) were included in a modified intent-to-treat analysis. All 4 experimental arms had significantly higher HF enrolment rates compared with control (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). When comparing experimental arms, the diabetes-specific message with the EAC had a significantly higher enrolment rate (12.6%) than the diabetes-specific message alone (7.6%, p=0.0016).

Conclusions

Messages focused on diabetes were effective at increasing enrolment in a healthy food programme. The addition of a framed active choice to a message significantly raised enrolment rates in this population. These findings suggest that simple, low-cost interventions can enhance enrolment in health promoting programmes and also be pragmatically tested within those programmes.

Trial registration number

Keywords: DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY, health promotion, messaging, active choice, NUTRITION & DIETETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this randomised controlled trial, we found that diabetes-specific messaging strategies were effective at increasing enrolment in a healthy food programme among adults with diabetes.

The incorporation of a behavioural economics-based technique called ‘enhanced active choice’ that prompted an immediate decision was the most effective at increasing programme enrolment.

These findings speak to the potential of simple, low-cost interventions to promote engagement in programmes designed to encourage healthier behaviours in high-risk, high-cost populations.

Few demographic details were available on randomised participants, limiting conclusions regarding the generalisability of the findings to other populations.

While large differences in programme enrolment were observed, this does not necessarily translate into programme usage, diet and health outcomes. Still, enrolment is a critical first step.

Introduction

Considerable evidence demonstrates reduced cardiovascular complication risk in adults with type 2 diabetes who consume a healthier diet.1–4 Maintaining a healthy diet, however, is a considerable challenge for many. One barrier may be the cost of healthy foods.5 Financial savings can promote healthier food purchases.6–8 Randomised interventions have demonstrated that participants who receive monetary discounts on healthy food items purchase greater quantities of fruits and vegetables compared with those who receive no discounts or who only receive nutritional education.7 8

The HealthyFood (HF) programme offered by Discovery Health's Vitality wellness programme offers cashback rewards for healthy food purchases. Discovery Health is the largest commercial health insurer in South Africa, serving ∼2.6 million of the 8 million South Africans with private health insurance (16% of the population is privately insured).9 Available to all Discovery Health members is the Vitality wellness programme, an incentivised health promotion programme; membership is voluntary and costs only a small amount per year.10 Included with Vitality are benefits ranging from gym subsidies to discounted Weight Watchers memberships. HF, one of the largest Vitality initiatives, is a three-tiered incentive programme designed to encourage a healthier diet by offering monthly cashback payments on healthy food purchases (examples of eligible foods are included in an online supplementary appendix). On initial HF activation, members are eligible for 10% cashback monthly. By completing an online health risk assessment and an in-person health screening, members can increase their monthly cashback amount to 25%. While this benefit is available at no additional cost to all Vitality members, immaterial of age or health status, there is particular interest in increasing current engagement in HF among individuals with high-risk, diet-sensitive health conditions such as diabetes. Currently, less than half of Vitality's ∼31 000 South African members with type 2 diabetes are enrolled in the HF programme.

bmjopen-2016-012009supp_appendix.pdf (83.9KB, pdf)

Tackling barriers to HF enrolment is a necessary first step to increasing programme engagement and, hopefully, improving diets. Improved messaging about HF to increase its salience for individuals with diabetes could be a low-cost way to increase HF programme enrolment. Past work demonstrates the importance of message content and framing on promoting subsequent health behaviours, ranging from organ donor registration to vaccine adherence.11–13 Targeted and tailored messages, for example, those designed for and sent to individuals with a certain condition, are more effective at shifting behaviour than more generic messages.11 The effectiveness of messages can also vary by whether a message is gain-framed or loss-framed (framed to emphasise the potential gains or losses relating to performing or not performing the targeted health behaviour).14 15 While some messaging studies targeting low-risk behaviours such as dietary changes or exercise suggest that gain-framed messages may be more effective than loss-framed messages,14 when financial losses are a highlighted consequence of not engaging in the targeted behaviour, the reverse pattern has been observed.16

These types of message framing strategies may also prompt more immediate action. Given the financial benefits of enrolling in HF, some members may intend to enrol but postpone the task assuming the process is overly time-consuming or complex. To combat this present bias (the natural tendency to overweight the upfront ‘costs’ of something compared with the future or long-term benefits),17 we tested a behavioural economics-based approach that asked participants to make an immediate ‘active choice’. This choice was further ‘enhanced’ by both gain-framing and loss-framing that highlighted the relative benefit of the preferred option (HF enrolment) and the losses of the non-preferred option (not enrolling).18 Past work using ‘enhanced active choice’ has shown success in increasing health-related behaviours ranging from influenza vaccination to automated pharmacy refill enrolment.18

In this study, we compared the effectiveness of diabetes-focused messaging strategies in increasing HF enrolment among Vitality members with type 2 diabetes. We hypothesised that messages that are more personalised and relatable, as well as those that prompt immediate action, would increase the rate of enrolment.

Methods

Study design

Eligible study participants were identified by the Vitality team. No formal consent process was required given the existing language in the Vitality membership agreement. The study statistician generated a randomisation list that was sent to Vitality who then linked it with the eligible member database according to the study ID. Using a simple randomisation scheme, participants were assigned to one of five study arms with equal chance. Automated email messages were generated and sent according to arm assignment. The analytic team had no contact with the study participants. Since this study addressed alternative messages by study arm, participants were not blinded to the assigned intervention.

Study population

Eligible participants lived in South Africa, were Vitality members aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, were not yet enrolled in HF, and were registered on the Vitality website (reflecting internet access and an available email address). Vitality members with type 2 diabetes were identified based on billing codes for diabetes along with any pharmacy codes for oral hypoglycaemic medications (not prescribed to patients with type 1 diabetes).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was HF enrolment at 1 month, collected using Vitality internal, electronic tracking systems. An intended secondary outcome was participants' interaction with the messages, specifically undelivered emails, unread emails, clicks to the embedded link to the HF enrolment page, time spent on the Vitality website, and initiation of the enrolment process. Unfortunately, technical issues within the electronic data collection system prevented these data from being captured.

Member involvement

Vitality members were not involved in the research design or in the selection of outcome measures.

Study intervention

Eligible members were randomised to one of the five study arms with equal chance: (1) control arm (no message), (2) a diabetes-specific message, (3) a message with a recommendation to participate in HF written from the perspective of a Vitality member with diabetes, (4) a message with a recommendation to participate in HF from a physician with diabetes expertise, or (5) the diabetes-specific message from arm 2 paired with an ‘enhanced active choice’. All tested messages were written by the study team, delivered via email, and contained common elements: a personalised subject line, a description of the HF benefit, mention of two potential health benefits for individuals with diabetes (better sugar control and weight management), and a link to initiate enrolment.

The diabetes-specific message contained only the elements described above. The diabetes-specific message with an ‘enhanced active choice’ included the following choices, which were designed to make more salient the advantages/disadvantages of enrolling/not enrolling: ‘Yes! I want to activate the HealthyFood benefit and get up to 25% cash back on the healthy food I buy.’ or ‘No, I'd prefer not to activate and continue paying full price for my healthy food purchases.’ The ‘Yes’ checkbox took participants directly to the HF enrolment site. The ‘No’ box linked to an internal website informing participants that they could still enrol at a later time. The diabetes-specific messages with and without the ‘enhanced active choice’ used in the study are included as online supplementary figures.

bmjopen-2016-012009supp_figures.pdf (393.3KB, pdf)

The intervention occurred in June and July 2015. We sent three email messages (an initial message plus two reminders) to participants in the experimental arms. All messages were separated by at least 2 days. Before the second and third messages, participant data were refreshed and only participants who had not signed up for HF were sent reminders.

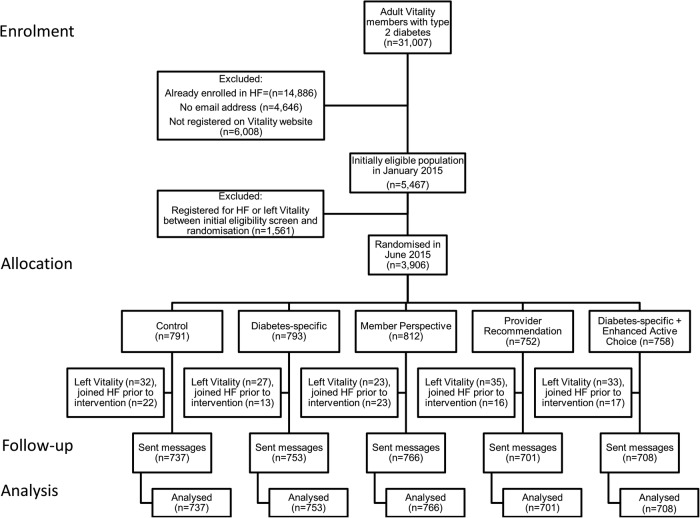

Statistical analysis

There were 5467 individuals determined to be initially eligible in January 2015 (figure 1). After excluding participants due to enrolment in HF prior to the intervention and departures from the Vitality programme, we estimated that at least 3500 individuals would still meet eligibility criteria at the time of randomisation and study launch in June 2015. The initial sample was identified several months before the launch to allow study participants ample time to have learnt about HF from other sources (eg, Vitality website and marketing communications) and enrol if interested. The primary end point of interest was a binary indicator of enrolment; pairwise hypothesis tests of enrolment rates were planned across the five arms, for a total of 10 possible comparisons. The anticipated sample size of 3500 provided 80% power to detect a 3% pairwise difference between the proportions of participants who enrolled in HF with significance testing conducted at the Bonferroni-corrected significance level of 0.005 (0.05/10) to account for the 10 pairwise between-arm comparisons and pessimistically allowing for up to 10% further exclusions. The baseline monthly enrolment rate was estimated at ∼1%/month. We compared the proportion enrolled between arms using a Fisher's exact test. All data analyses were performed using R software (V.3.2.1; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Figure 1.

Participant enrolment, allocation, follow-up and analysis. HF, HealthyFood.

Results

Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram for the study (the completed CONSORT checklist is included as an online supplementary material document). There were 3906 randomised participants, and 3665 in the analysis cohort of current members not enrolled in HF at the time of intervention launch. Age and gender were similar between the arms (table 1).

Table 1.

Member characteristics*

| Control | Diabetes-specific | Member perspective | Provider recommendation | Diabetes-specific+e nhanced active choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=3665) | n=737 | n=753 | n=766 | n=701 | n=708 |

| Female (%) | 145 (19.7) | 152 (20.2) | 152 (19.8) | 134 (19.1) | 146 (20.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.9 (10.9) | 55.2 (10.7) | 55.0 (10.8) | 55.4 (10.0) | 56.0 (10.6) |

*This is the age and gender distribution of the primary Vitality member (not necessarily the email reader or primary shopper).

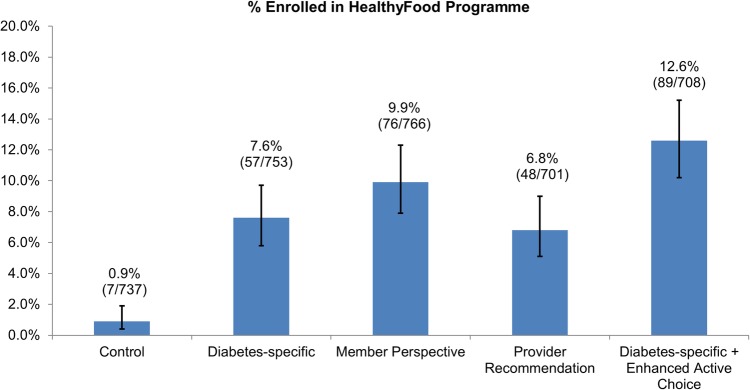

Figure 2 reports enrolment rates across arms. All interventions were superior to control at the Bonferroni-corrected significance level (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). The ‘enhanced active choice’ arm revealed the largest difference compared with control (12.6% vs 0.9%, p<0.0001). Those in the ‘enhanced active choice’ arm had a higher rate of enrolment than both those receiving the diabetes-specific message alone (12.6% vs 7.6%, p=0.0016) and those receiving the message with the physician's recommendation (12.6% vs 6.8%, p=0.0003). Compared with those who received the message with the physician's recommendation of HF, those who received the message written from the perspective of another member with diabetes had higher enrolment rates (6.8% vs 9.9%, p=0.0386), but this difference was not significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level. None of the other pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences in enrolment rates.

Figure 2.

Enrolment in HealthyFood programme by study arm. Note: Vertical error bars depict 95% Clopper and Pearson confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this randomised controlled trial of adults with diabetes, we found that four diabetes-specific messaging strategies were more effective at increasing enrolment in a healthy food benefit than current practice.

The ‘enhanced active choice’ arm had the highest rate of HF enrolment. This simple, no-cost messaging approach could be used more widely to help people take action to address their underlying risks. ‘Enhanced active choice’ is well suited to conditions where people must make an affirmative choice (because defaults are seen as too presumptuous), yet most people would see clear advantages of a particular path if those were highlighted. In the context of enrolment into an automatic pharmacy refill programme, for example, default enrolment might be seen as too aggressive, because credit cards would be charged on prescription refills and some people would find that too invasive. However, encouraging participants to actively select automatic referrals is a middle ground.18 Moreover, encouraging an immediate choice (eg, by preventing people online from proceeding to the next page without accepting or declining) prevents potential procrastination. Note that we stopped short of actually requiring participants to make a decision; in many contexts, such as in signing up for benefits, it would be relatively easy to do that, but here we took the less paternalistic approach of simply encouraging participants to make a decision and highlighting some of the relevant advantages and disadvantages.

While an enrolment rate of 12.6% (the highest observed rate in the ‘enhanced active choice’ arm) may seem to some a small step towards achieving 100% HF enrolment, the results must be viewed in the context of past Vitality HF marketing campaigns and the cost of the tested interventions. Past Vitality HF marketing campaigns have resulted in enrolment rates of only 1–3%, well below the rates seen in all of the intervention arms. So while an ‘enhanced active choice’ messaging strategy is unlikely to result in 100% enrolment among members with diabetes, it could be a first resource-conserving step if 12.6% of the currently unenrolled population enrolled in HF without prompting from a paper mailer or a personal phone call. Given the ‘light touch’ nature of the tested interventions, we focused only on differences in programme enrolment. Still, HF enrolment is a potential first step towards dietary change; past work (analyses of member surveys and grocery scanner data) has demonstrated that HF enrollees make positive changes in their food choices, increasing healthy choices and decreasing unhealthy ones.19 20 It is important that future studies explore the downstream effects of HF enrolment, specifically programme usage, dietary changes and health outcomes.

The study design had several limitations. First, the generalisability of the study findings to other contexts was limited by the current uniqueness of Vitality and the HF programme, as well as the sparse demographic information available. We had limited information on member characteristics. For example, table 1 presents the age and gender of the primary Vitality members, but we did not collect any information about who received the study emails or who regularly does the household grocery shopping. Second, the use of a non-active control did not allow for direct comparisons between the tested diabetes-specific messages and less targeted messages. Third, we were not able to assess message opening or partial enrolment. Fourth, this study was limited to those who had already established an online account with Vitality, who may already be more motivated to participate and are easier to reach electronically. Vitality members without established accounts might benefit even more from such interventions but are harder to reach.

This study also has strengths. The design of this study reveals how real-time operational systems can become laboratories for health behaviour change; this study was conducted pragmatically, in the same setting in which it would be later implemented. This design lends the findings a high degree of external validity with regard to the ability to successfully incorporate these types of framed messaging strategies into Vitality's health promotion outreach efforts for similar populations.

While many interventions to improve health are operationally intensive and costly, some, like those tested here, are not. The results of this trial demonstrate that targeted, framed messages can help nudge individuals with diabetes to enrol in a healthy food programme. This step could be the first one towards healthier food choices, an essential contributor to ideal diabetes management and reduced cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Elle Alexander for her assistance with initial study design and conception.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the listed authors have met the requirements for authorship. AG, the lead author, was responsible for overseeing study conception and design, communication between team members, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript construction and manuscript revision. JP, DP and CB, who are all affiliated with Vitality, were responsible for day-to-day study operations (eg, sending of the email messages and abstracting enrolment data from internal Vitality tracking systems to send to the Penn team). Given their affiliations with Vitality, the study's funder, JP, DP and CB were not involved with data analysis and interpretation and only provided general feedback on the manuscript (ie, they had no influence on how findings were presented and interpreted). PAS, the study's lead biostatistician, oversaw all statistical planning, data transfer from the Vitality team, data analysis and interpretation, and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. JF and AMB contributed to study conception and design, result interpretation, and provided detailed feedback on the manuscript. ABT and DAA contributed content expertise in the areas of biostatistics and behavioural economics, respectively, and both were actively involved in manuscript preparation. KGV served as the principal investigator on the study. He contributed his significant expertise in behavioural economics and randomised interventions to study conception and design, data interpretation and manuscript construction. KGV is the guarantor of this manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by an unconditional award from Vitality USA.

Disclaimer: The study topic, research question and study design were at the discretion of the lead author and not the funder. Though several Vitality USA and Discovery Vitality employees were involved in helping to operationalise the study, these individuals were not involved in data analysis or interpretation and only provided general feedback on the manuscript (ie, had no control over how findings were presented and interpreted).

Competing interests: PAS, ABT and KGV have received research funding from the Vitality Institute. JP and DP are employees of Discovery Vitality, and CB is an employee of Vitality USA. Given these relationships, these three individuals were not involved in data analysis but provided only operational support and expertise. DAA and KGV are both principals at the behavioural economics consulting firm, VAL Health. KGV also has received consulting income from CVS Caremark and research funding from Humana, CVS Caremark, Discovery (South Africa), Hawaii Medical Services Association and Merck. ABT serves on the scientific advisory board of VAL.

Ethics approval: University of Pennsylvania IRB and the University of Witwatersrand Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. (4). Foundations of care: education, nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation, psychosocial care, and immunization. Diabetes Care 2015;38(Suppl 1):S20–30. 10.2337/dc15-S007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM et al. , PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:485–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon NF, Salmon RD, Franklin BA et al. . Effectiveness of therapeutic lifestyle changes in patients with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and/or hyperglycemia. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:1558–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA et al. . A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1563–71. 10.1056/NEJMoa061883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G et al. . Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2013;3:e004277 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An R. Effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: a review of field experiments. Public Health Nutr 2013;16:1215–28. 10.1017/S1368980012004715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geliebter A, Ang IY, Bernales-Korins M et al. . Supermarket discounts of low-energy density foods: effects on purchasing, food intake, and body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:E542–8. 10.1002/oby.20484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball K, McNaughton SA, Le HN et al. . Influence of price discounts and skill-building strategies on purchase and consumption of healthy food and beverages: outcomes of the Supermarket Healthy Eating for Life randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:1055–64. 10.3945/ajcn.114.096735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayosi BM, Benatar SR. Health and health care in South Africa—20 years after Mandela. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1344–53. 10.1056/NEJMsr1405012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel DN, Nossel C, Alexander E et al. . Innovative business approaches for incenting health promotion in sub-Saharan Africa: progress and persisting challenges. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2013;56:356–62. 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav 2003;27(Suppl 3):S227–32. 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s3.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreuter MW, Caburnay CA, Chen JJ et al. . Effectiveness of individually tailored calendars in promoting childhood immunization in urban public health centers. Am J Public Health 2004;94:122–7. 10.2105/AJPH.94.1.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Behavioral Insights Team. Applying Behavioural Insights to Organ Donation 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/267100/Applying_Behavioural_Insights_to_Organ_Donation.pdf (access date: November 24, 2016)

- 14.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med 2012;43:101–16. 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: the role of message framing. Psychol Bull 1997;121:3–19. 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R et al. . Framing financial incentives to increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:385–94. 10.7326/M15-1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. 5th edn 2015. Jossey-Bass Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller PA, Harlam B, Loewenstein G et al. . Enhanced active choice: a new method to motivate behavior change. J Consum Psychol 2011;21:376–83. 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sturm R, An R, Segal D et al. . A cash-back rebate program for healthy food purchases in South Africa: results from scanner data. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:567–72. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.An R, Patel D, Segal D et al. . Eating better for less: a national discount program for healthy food purchases in South Africa. Am J Health Behav 2013;37:56–61. 10.5993/AJHB.37.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012009supp_appendix.pdf (83.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012009supp_figures.pdf (393.3KB, pdf)