Abstract

Objectives

In 2010, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) replaced the 7-valent vaccine (introduced in 2006) for vaccination against invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPDs), pneumonia and acute otitis media (AOM) in the UK. Using recent evidence on the impact of PCVs and epidemiological changes in the UK, we performed a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) to compare the pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) with PCV-13 in the ongoing national vaccination programme.

Design

CEA was based on a published Markov model. The base-case scenario accounted only for direct medical costs. Work days lost were considered in alternative scenarios.

Setting

Calculations were based on serotype and disease-specific vaccine efficacies, serotype distributions and UK incidence rates and medical costs.

Population

Health benefits and costs related to IPD, pneumonia and AOM were accumulated over the lifetime of a UK birth cohort.

Interventions

Vaccination of infants at 2, 4 and 12 months with PHiD-CV or PCV-13, assuming complete coverage and adherence.

Outcome measures

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was computed by dividing the difference in costs between the programmes by the difference in quality-adjusted life-years (QALY).

Results

Under our model assumptions, both vaccines had a similar impact on IPD and pneumonia, but PHiD-CV generated a greater reduction in AOM cases (161 918), AOM-related general practitioner consultations (31 070) and tympanostomy tube placements (2399). At price parity, PHiD-CV vaccination was dominant over PCV-13, saving 734 QALYs as well as £3.68 million to the National Health Service (NHS). At the lower list price of PHiD-CV, the cost-savings would increase to £45.77 million.

Conclusions

This model projected that PHiD-CV would provide both incremental health benefits and cost-savings compared with PCV-13 at price parity. Using PHiD-CV could result in substantial budget savings to the NHS. These savings could be used to implement other life-saving interventions.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, IMMUNOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study incorporates the most recent evidence on pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) efficacy/effectiveness as well as the latest epidemiological data from the UK (2014). Moreover, model parameters have been validated by a panel of external experts.

The model is based on a previously published PCV cohort model, and an extensive sensitivity analysis has been performed to reflect uncertainty in model assumptions.

Results are timely and relevant for policy. Current decisions did not anticipate such a large serotype replacement in the elderly, which may warrant a re-evaluation of the budget allocated to PCV based on the health benefits actually generated by the current programme.

Static cohort models integrate net herd protection (ie, herd protection and type replacement combined) using a fixed effect at equilibrium. However, dynamic models may be more appropriate to capture these effects over time and in relation to population characteristics and vaccine coverage.

Owing to the lack of head-to-head studies comparing the two vaccines, some efficacy estimates are from different studies and might not be directly comparable. However, model assumptions are conservative and a panel of independent experts reviewed all available evidence to select the most comparable efficacy estimates for both vaccines.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp) infection is established as a cause of significant morbidity and mortality in infants and young children worldwide.1 The WHO estimated that in 2008 5% of all-cause mortality in children <5 years old was attributable to pneumococcal infections worldwide.2 Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), mainly meningitis and bacteraemia, is a clinical manifestation of infection with Sp. The pneumococcus also plays a significant role in causing non-invasive infections such as pneumonia and acute otitis media (AOM).1

In the UK, ∼5000–6000 cases of IPD were reported annually to Public Heath England from laboratories in England and Wales before the introduction of routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV). In addition, there were an estimated 40 000 hospitalisations due to pneumococcal pneumonia, 40 000 general practitioner (GP) consultations for pneumococcal-related community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and over 63 000 GP consultations for pneumococcal otitis media (OM) in England and Wales each year.3

The 7-valent PCV (PCV-7) has reduced the incidence of IPD in the UK since its introduction in 2006.4 However, alongside this reduction in IPD burden, antibiotic resistance and a shift in serotype distribution involving Sp serotypes not covered by the vaccine have been observed.5–7 This shift in serotype distribution often leads to replacement in carriage and disease, with the potential of extension to other pathogens. It has even been shown that vaccination with PCV-7 may lead to a rise in non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi)-related AOM.8 Therefore, the 13-valent PCV (PCV-13, Prevnar 13, Pfizer, Pearl River, New York, USA) and the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV, Synflorix, GSK group of companies, Rixensart, Belgium) were introduced in 2009.9 PHiD-CV includes three additional Sp serotypes (1, 5 and 7F) compared with PCV-7, while PCV-13 includes these additional serotypes and three further Sp serotypes (3, 6A and 19A). Although Sp serotypes 6A and 19A are not included in PHiD-CV, clinical evidence suggests that PHiD-CV offers marked protection against these cross-reactive Sp serotypes.10–15 So far, there is no conclusive evidence that PCV-13 prevents IPD, AOM or pneumonia due to serotype 3.16 17 Furthermore, in contrast to PCV-7 and PCV-13, PHiD-CV has the additional potential to target NTHi-related AOM, due to the employment of protein D derived from NTHi as a carrier protein for the majority of its conjugates.18 19 This is important, as AOM represents a major indication for the prescription of antibiotics in infants.20 21 Significant antibiotic resistance has been observed in Sp22–24 and NTHi bacteria,25 and the increasing resistance to antibiotics is globally recognised as a health policy concern.

Infectious disease modelling integrates data from multiple sources (eg, epidemiological, economic, demographic and biological) to predict the impact of new interventions in a given population. In 2012, a Markov cohort model evaluating the cost-effectiveness of PHiD-CV versus PCV-13 for Canada and the UK was published by Knerer et al,26 using epidemiological information from 2006 to 2007 (ie, before the introduction of PCV-7). Since then the situation has changed, in terms of epidemiology in the UK (eg, serotype distribution and IPD incidence), and because more evidence is now available regarding the impact of both vaccines (eg, protection against cross-reactive Sp types 6A and 19A). Here, we present an updated cost-effectiveness analysis comparing PHiD-CV with PCV-13 in the current UK setting.

Materials and methods

Model overview

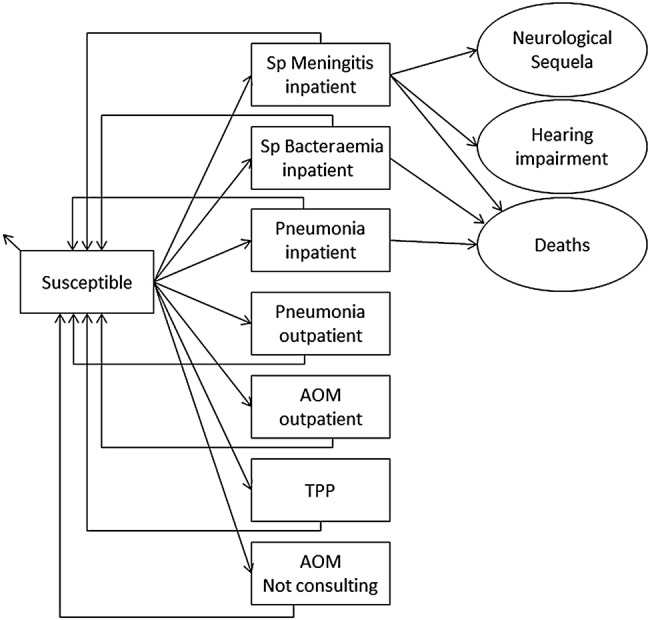

The Markov model described here is conceptually identical to the model published earlier by Knerer et al and is essentially an update of that model.26 Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the model. Model input data and assumptions were based on published data where possible, and were validated where appropriate by a panel of independent experts (GSK PHiD-CV Health Economics Advisory Board, Leuven, Belgium, September, 2013).

Figure 1.

Model flow diagram. Rectangles represent mutually exclusive health states. Age-specific incidences are applied monthly to the susceptible population. Circles (sequelae and death) and small arrows (natural death) represent the proportion of the population removed from the model. Costs and benefits are computed monthly and aggregated over the cohort's lifetime. Non-consulting AOM episodes are accounted for in the quality of life calculation. AOM, acute otitis media; Sp, Streptococcus pneumoniae; TTP, tympanostomy tube placement.

This model was used to estimate the epidemiological and economic impact of a universal infant pneumococcal vaccination programme in the UK. The model simulated the impact of vaccination on invasive and non-invasive diseases caused by Sp and NTHi-related infections in a birth cohort. It compared two PCVs, PCV-13 (currently available in the UK) and PHiD-CV, each given in a three-dose (2+1) schedule with vaccine doses administered at 2, 4 and 13 months of life.

Individuals in the birth cohort were followed in the model over a lifetime with a cycle time of 1 month. During each model cycle, the probability of an individual entering a specific health state was governed by age-specific incidence rates and applicable vaccine efficacy (VE) levels. These transition probabilities determined hospitalisation rates and frequency of medical visits associated with the disease conditions considered in the model. Costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) lost associated with the model outcomes (eg, cases, medical visits, hospitalisations) were accumulated over the cohort's lifetime. The base-case analysis took the perspective of the healthcare provider in the UK, the National Health Service (NHS), and therefore accounted only for direct medical costs. An additional analysis accounting for productivity loss was conducted, providing a broader perspective that may further help inform the decision-making process.

Epidemiological data

Demography

The size of the birth cohort in the UK (n=792 616 infants; reference year mid-2013) and age-specific overall monthly mortality rates for the general population were obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS; see online supplementary table S1 in file 1).27 28

bmjopen-2015-010776supp1.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)

Invasive pneumococcal diseases

This section describes the parameters used for the Sp meningitis and bacteraemia natural histories in figure 1. In the model, all cases of IPD were assumed to be hospitalised. Transitions from the susceptible state to Sp meningitis and bacteraemia requiring inpatient admission were derived from age-specific hospital admission data from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database 2013–2014, and population age distribution data from the ONS (see online supplementary table S2 in file 1).28 29 In the HES database, the International Classification of Disease V.10 (ICD-10) codes used for meningitis and bacteraemia are G00.1 (pneumococcal meningitis) in the primary diagnosis fields and A40.3 (sepsis due to Sp) in all diagnosis fields, respectively.29 All diagnosis fields were used for bacteraemia as this disease condition occurs frequently as a complication. The pathogen-specific ICD-10 codes applied are in line with the definitions in studies used for VE estimates (see Vaccine efficacy section). Following meningitis, children and adults can develop long-term neurological sequelae and hearing impairment. The proportion of children with neurological sequelae (7.0%) and hearing impairment (13.3%) were based on Pomeroy et al30 and a meta-analysis of 11 studies,31 respectively. For adults, the proportion of meningitis cases with neurological sequelae (19.0%) and hearing impairment (25.4%) were based on the weighted average of two studies by Kastenbauer and Pfister32 and Auburtin et al.33 As data are limited in the UK, we conservatively assumed no long-term sequelae following an episode of bacteraemia. Similarly, cases and deaths due to NTHi ID were not included in the base-case analysis. Case-fatality ratios (CFRs) for Sp meningitis and bacteraemia were extracted from Johnson et al34 and Melegaro and Edmunds,35 respectively. For children aged ≤4 years, CFR data were further updated using Ladhani et al.7

Pneumonia

Inpatient incidence rates of all-cause pneumonia were derived from the HES database using ICD-10 codes J13 (Sp), J14 (Hi), J15.9 (bacterial pneumonia, unspecified) and J18.1/8/9 (lobar pneumonia or unspecified (pneumonia/pathogen); see online supplementary table S3 in file 1).29 The broad set of ICD-10 codes considered is in line with efficacy end points reported in published clinical trials not discriminating between causative pathogens (see Vaccine efficacy section). Age-specific CFRs for inpatient pneumonia were based on data from Melegaro and Edmunds.35 Outpatient incidence rates were based on 2010 data from the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) in England and Wales36 and no mortality was assumed.

Acute otitis media

Outpatient incidence rates for AOM episodes (not visits) were taken from the RCGP 2011 Annual Report (ICD-9 codes 381.0—acute non-suppurative OM, 382.0—acute suppurative OM and 382.9—unspecified OM).36 The proportion of AOM cases caused by Sp (35.9%), NTHi (32.3%) and other causative agents (31.8%) were extracted from the review of Leibovitz et al.37 AOM cases caused by Sp were further distributed between pneumococcal serotypes based on a multinational meta-analysis of nine data sets published by Hausdorff et al.38 The age-specific rate of tympanostomy tube placement (TTP) was obtained from the HES database using the procedural code D15.1 (myringotomy with insertion of ventilation tube through the tympanic membrane; see online supplementary table S4 in file 1).39 The model accounted for the reduced quality of life of patients with AOM not consulting a GP using an adjustment factor, defined as the ratio of GP consultations from Williamson et al40 over the total number of AOM cases from Melegaro and Edmunds.35 Finally, our model assumed no complications, long-term sequelae or deaths related to AOM.

Costs

All costs were reported in British pounds sterling (£) with 2014 as the reference year. Costs prior to 2014 were adjusted on the basis of the UK healthcare service cost index (V.02 May 2013).41 The direct annual costs per acute episode are given in the online supplementary table S1 in file 2. NHS reference costs (2013–2014) were used to identify cost components including those dependent on disease conditions: for example, ambulance transfer, accident and emergency investigation, intensive care unit stay, CT/MRI scanning or X-ray, ultrasound, weighted average cost of hospital stay and cost of primary care consultation, using information from Melegaro and Edmunds35 where applicable. Costs associated with meningitis consisted of two components, the costs of treating the initial meningitis episode and the follow-up costs associated with long-term sequelae (neurological sequelae and hearing loss) incurred over the remaining lifetime. The incidences of sequelae for bacteraemia, all-cause pneumonia and AOM were conservatively set to zero in the model. In these instances, disease-related treatment costs were assumed to be incurred within 1 month with no long-term costs due to sequelae.

bmjopen-2015-010776supp2.pdf (20.7KB, pdf)

In the base-case scenario, price parity was assumed for PHiD-CV and PCV-13. Total vaccine costs per dose were estimated from the list price, accounting for 5% wastage and an administration cost of £7.64 per dose.42 The resultant total vaccine cost per dose was estimated at £48.88 based on a 0.5 mL prefilled syringe. Vaccination coverage was assumed to be 100%, in line with vaccination rates commonly obtained with national immunisation programmes in the UK.43 Furthermore, a complete course (three doses) with perfect adherence (100%) was assumed. Although these assumptions on coverage and adherence are simplified, they affect both vaccines equally and therefore should not have an impact on the cost-effectiveness ratio.

Utilities

Three types of utility values were used in the model. Normative utility values represent the age-specific utility in healthy individuals.44 The QALY loss per episode was computed for acute diseases using the formula (1−QALY weight)×(duration of episode in days/365 days). The QALY loss per year (1−QALY weight) was used for long-term conditions (see online supplementary table S1 in file 3).35 45–49 In the literature, studies looking at long-term meningitis sequelae have variable follow-up times (5–20 years).50 In our model and others, disutility weights for long-term sequelae were incurred for the time remaining until the end of the study time horizon.

bmjopen-2015-010776supp3.pdf (53.5KB, pdf)

Vaccine efficacy

In the base-case analysis, the impact of vaccination was assessed including both direct and indirect effects of protection (herd protection). To estimate the direct effect of vaccination, published estimates of VE were applied to the age-specific disease incidence in sequential model cycles. The VE estimates used in the model and described in this section have been validated by a panel of independent experts (GSK PHiD-CV Health Economics Advisory Board, Leuven, Belgium, September, 2013; table 1).

Table 1.

Model input data: VE

| VE* % (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| PHiD-CV | PCV-13 | Reference/assumption | |

| IPD | |||

| Ten common serotypes for PHiD-CV and PCV-13† | 94.7‡ (87.0 to100.0) |

94.7‡ (87.0 to100.0) |

Whitney et al13 |

| Serotype 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 (26% in SA) |

Andrews et al17 |

| Serotype 6A | 76.0 (39.0 to 90.0) |

94.7 (87.0 to 100.0) |

Vesikari et al56 Whitney et al13 |

| Serotype 19A | 62.0 (20 to 85) |

94.7 (87.0 to 100.0) |

Whitney et al13 Jokinen et al15 |

| Pneumonia | |||

| Per cent of reduction in hospitalisations | 23.4 (8.8 to 35.7) |

23.4 (8.8 to 35.7) |

Tregnaghi et al12 |

| Per cent of reduction in GP visits | 7.3 (2.1 to 12.3) |

7.3 (2.1 to 12.3) |

|

| AOM without TTP | |||

| Ten common serotypes for PHiD-CV and PCV-13 | 69.9 (29.8 to 87.1) |

69.9 (29.8 to 87.1) |

Tregnaghi et al12 |

| Non-vaccine type Streptococcus pneumoniae | −33.0 (−33.0 to 15.0) |

−33.0 (−33.0 to 15.0) |

Eskola et al67 |

| Serotype 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | As for IPD |

| Serotype 6A | 63.7 (−13.9 to 88.4) |

69.9 (29.8 to 87.1) |

Prymula et al10 Tregnaghi et al12 |

| Serotype 6C | 0.0 | 63.7 (−13.9 to 88.4) |

Same as 6A for PHiD-CV |

| Serotype 19A | 45.8§ (−33 to 15) |

69.9 (29.8 to 87.1) |

Tregnaghi et al12 |

| NTHi | 21.5 (−43.4 to 57.0) |

−11.0 (−34 to 8) |

Tregnaghi et al12 Eskola et al67 |

| AOM with TTP | |||

| TTP | 50.9 | 30.6 | Extrapolated¶ from Fireman et al68 and Palmu et al69 |

*All VE estimates have been validated by an expert panel.

†Included serotypes were 1, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F.

‡PHiD-CV and PCV-13 were assumed to have the same serotype efficacy for the 10 common serotypes as the average VE of PCV-7 vaccine serotypes (94.7%).

§PHiD-CV efficacy was estimated taking the efficacy ratio of the vaccines in IPD (vaccine serotypes).

¶Extrapolated VE estimates were well in agreement with findings of the FinIP study;70 the boundaries reflect 95% CIs that were used in the sensitivity analyses.

AOM, acute otitis media; FinIP, Finnish Invasive pneumococcal disease; GP, general practitioner; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; JCVI, Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation; PCV-13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PHiD-CV, 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine; SA, sensitivity analysis; Sp, Streptococcus pneumoniae; TTP, tympanostomy tube placement; VE, vaccine efficacy.

Invasive pneumococcal diseases

Overall efficacy against meningitis and bacteraemia was computed for both vaccines based on the serotype-specific efficacy estimates from Whitney et al13 and the local serotype distribution derived from Waight et al (see online supplementary table S5a in file 1).51 52 The efficacy used for all vaccine serotypes included in PHiD-CV and PCV-13 was the average efficacy reported by Whitney et al against PCV-7 serotypes (serotype-specific efficacy estimates were not used as for some serotypes the number of cases was too small),13 except for serotype 3. Serotype 3 is included in PCV-13 but not in PHiD-CV. However, both PCV-13 and a precursor of PHiD-CV have failed to show significant efficacy against serotype 3,10 16 17 51 53–56 probably because of its thicker polysaccharide capsule.

In addition to efficacy against vaccine serotypes, large PCV clinical trials have shown that serotypes 19F and 6B can also induce protection against 19A and 6A, respectively, because they functionally belong to the same serogroup.11 13–15 Cross-protection against serotype 6A (76%) owing to serotype 6B (included in all PCVs) has been demonstrated in PCV-7 trials.13 57 Finally, large clinical trials in Brazil,11 Canada14 and Finland15 have reported VE against 19A in IPD of 82%, 71% and 62%, respectively, which prompted an update of the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for PHiD-CV to include protection against 19A (the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval on 23 July 2015).58 59 In this analysis, we used the Finnish estimate for VE (62%) because it is based on a 2+1 PHiD-CV vaccination schedule administered in a European setting.15

Pneumonia

VE of PCVs against CAP has been assessed in several large-scale, randomised, controlled trials conducted in different settings.12 60–64 These trials have shown that protection against disease is not associated with the number of serotypes included in the vaccine formulation. Hence, the model assumed an efficacy of 23.4% against X-ray-confirmed consolidated CAP (which usually requires hospitalisation) and 7.3% against clinically suspected CAP (commonly managed on an outpatient basis) for both vaccines, based on a clinical trial of PHiD-CV.12 These estimates are conservative, as postmarketing surveillance data from Brazil have shown a reduction of 40% and 30% in pneumonia hospitalisations with PHiD-CV65 and PCV-13,66 respectively.

Acute otitis media

VE against all vaccine types except serotype 3 (same as for IPD16) was assumed to be 69.9% for both vaccines.12 VE against non-vaccine types was assumed to be −33.0% for both vaccines to account for serotype replacement.67 PHiD-CV cross-protection against serotype 6A (63.7%) was based on Prymula et al10 12 and the cross-protection against 19A (45.7%) was computed using the ratio of efficacy estimates between PHiD-CV and PCV-13 in conjunction for IPD. VE against NTHi-related AOM was assumed to be 21.5% for PHiD-CV.8 10 12 67 For PCV-13, the VE was −11.0%, as reported for its predecessor PCV-7.67 These efficacy estimates, in line with expert validation and with data reported by Tregnaghi et al,12 were applied to the respective serotypes, taking into account the frequency of these serotypes in causing AOM (see online supplementary table S5b in file 1).66 67 A similar approach was used for NTHi-related AOM. VE for both vaccines against AOM with TTP procedures was extrapolated using an exponential function based on the results of PCV-7 clinical trials68 69 and the relative ratio of overall AOM VE.70 These VE estimates were in agreement with the findings of the Finnish Invasive pneumococcal disease (FinIP) study.70 The higher efficacy of PHiD-CV compared with PCV-13 for AOM is reflected in the estimates of VE against TTP procedures (table 1).

Direct vaccine protection in children against IPD, pneumonia and AOM is age-specific. First, during the ramp-up phase VE increases to 50%, 90% and 100% of the type-specific and disease-specific VE estimates described above following the first, second and booster doses, respectively.12 68 Second, from 13 months (booster dose) to 3 years of age we assumed that VE does not wane.12 Finally, VE was assumed to wane exponentially from 3 to 10 years of age, after which the vaccine stops providing any direct protection to the vaccinated birth cohort.71 These assumptions are conservative, since data are now available showing that efficacy does not decrease exponentially after 3 years.12

Indirect or herd protection resulting from continual vaccination of sequential birth cohorts was taken into account for the entire population for IPD only (we conservatively assumed no herd protection for pneumonia and AOM). Serotype replacement offsets the incremental effect of indirect protection. In the model, indirect protection adjusted for the opposing impact of serotype replacement was applied as a fixed effect to the residual disease incidence. This net indirect effect was estimated at 30%, removing the necessity to account separately for the effect of serotype replacement.72 73 All efficacy estimates and the net indirect effect applied in the model are in line with Tregnaghi et al12 and were validated by a panel of experts (GSK PHiD-CV Health Economics Advisory Board, Leuven, Belgium, September, 2013). Assumptions regarding net herd protection were varied in scenario analyses (15% and 0%), as recent data from the UK suggest high levels of serotype replacement in adults.51 74 75

Cost-effectiveness and sensitivity analysis

Health benefits and costs were accumulated over the cohort's lifetime and discounted at a rate of 3.5% to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER).76 The ICER of PHiD-CV compared with PCV-13 (expressed in £/QALY) was computed by dividing the difference in costs between the two vaccines by the difference in health outcomes.

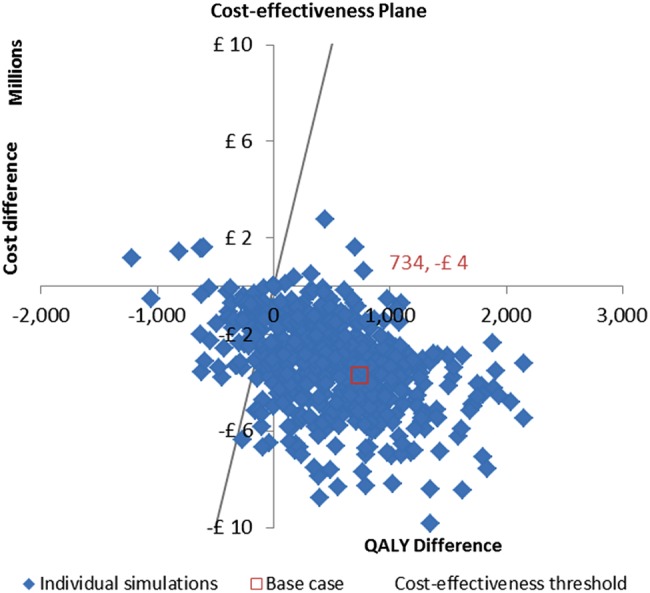

Sensitivity analyses were performed to capture the effects of parameter uncertainty on model predictions and identify the most influential parameters. One-way sensitivity analyses were performed by varying each parameter one by one within a range of plausible estimates and ranking the parameters based on their impact on the results. In addition, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed by simultaneously varying all parameters to capture their conjoint uncertainty (500 different parameter sets sampled from probability distributions). Results from the PSA were plotted in a cost-effectiveness plane (QALYs vs costs), along with the base-case ICER estimate. Ranges used in the one-way sensitivity analyses and the probability distributions used in the PSA are provided in the online supplementary table S1 in file 4.

bmjopen-2015-010776supp4.pdf (109.5KB, pdf)

In addition to sensitivity analyses, we performed scenario analyses on specific model assumptions to better understand their impact on the results. Alternative scenarios explored were as follows: (1) net herd protection reduced to 15% and 0% to explore the impact of the increased serotype replacement observed in recent years in adults in the UK.51 74 75 (2) Efficacy against serotype 3 increased to 26% for PCV-13 (non-significant result from17). (3) NTHi ID (meningitis and bacteraemia) and NTHi pneumonia included in the model; in this scenario, the incidence of NTHi ID was assumed to be 5% of all Sp IPD cases in children aged <10 years, with a CFR of 10%. (4) Productivity loss, in which in addition to direct medical costs the model also estimated the time lost from work by patients of working age (18–75 years) or time lost from work by parents caring for their sick children. For patients, the time loss estimates were multiplied by the estimated annual earnings at the individual's age, and for working parents (aged 18–49 years) the time estimates were multiplied by an average annual earnings of £20 375 (see online supplementary tables S2 and S3 in file 2).77 78 (5) Accounting for the difference in list price of both vaccines in the UK (£49.10/dose and £27.60/dose for PCV-13 and PHiD-CV, respectively).79

Results

Base-case analysis

Under our model assumptions, PCV-13 and PHiD-CV showed identical reductions in mortality due to IPD and all-cause pneumonia. The estimated impact on the number of IPD and pneumonia cases was also similar for both vaccines. However, PHiD-CV would prevent an additional 31 070 GP visits and 2399 AOM-related TTP procedures, compared with PCV-13 (table 2).

Table 2.

Model outcomes for the base-case analysis

| PHiD-CV | PCV-13 | Incremental (PHiD-CV vs PCV-13) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Health outcomes, undiscounted (n) | |||

| Pneumococcal meningitis | 266 | 265 | +1 |

| Pneumococcal bacteraemia | 720 | 719 | +1 |

| All-cause pneumonia* | 356 292 | 356 292 | 0 |

| AOM† related GP visits | 933 162 | 964 232 | −31 070 |

| AOM with TTP | 29 585 | 31 984 | −2 399 |

| Cases of meningitis sequelae | 86 | 86 | 0 |

| Deaths (meningitis, bacteraemia, pneumonia) | 90 437 | 90 437 | 0 |

| Total QALYs gained, undiscounted | 53 962 843 | 53 962 031 | 812 |

| Total QALYs gained, discounted | 18 981 547 | 18 980 813 | 734 |

| Economic outcomes (£k), undiscounted | |||

| Vaccination including administration | 115 997 | 115 997 | 0 |

| Pneumococcal meningitis | 1 953 | 1 948 | 5 |

| Meningitis sequelae | 4 592 | 4 579 | 12 |

| Pneumococcal bacteraemia | 4 548 | 4 542 | 6 |

| All-cause pneumonia* | 1 271 214 | 1 271 215 | −1 |

| AOM related GP visits | 42 925 | 44 355 | −1 429 |

| AOM with TTP | 33 777 | 36 516 | −2 739 |

| Total direct costs (£k), undiscounted | 1 475 006 | 1 470 151 | -4 145 |

| Total direct costs (£k), discounted | 297 248 | 300 930 | -3 682 |

| ICER, undiscounted | Dominant‡ | ||

| ICER, discounted | Dominant‡ | ||

*All-cause pneumonia includes patients hospitalised or only visiting the GP.

†Total AOM cases (GP visits+TTP+not consulting GP) for PHiD-CV (3 882 967) and PCV-13 (4 044 886) based on AOM adjustment factor (online supplementary table S4 in file 1).

‡PHiD-CV dominant because it provides both lower costs and higher effectiveness (larger number of QALYs) compared with PCV-13.

AOM, acute otitis media; GP, general practitioner; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; PCV-13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PHiD-CV, 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; TTP, tympanostomy tube placement.

Assuming price parity for both vaccines, PHiD-CV would reduce QALY loss by 734 QALYs (812 QALYs undiscounted) compared with PCV-13 and save £3.68 million (£4.14 million undiscounted) in direct medical costs to the NHS (dominant intervention). These results are due to fewer AOM-related GP consultations and in-hospital TTP procedures with PHiD-CV than PCV-13. For instance, the reduction in AOM-related GP visits alone would save £1.43 million to the healthcare system (table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

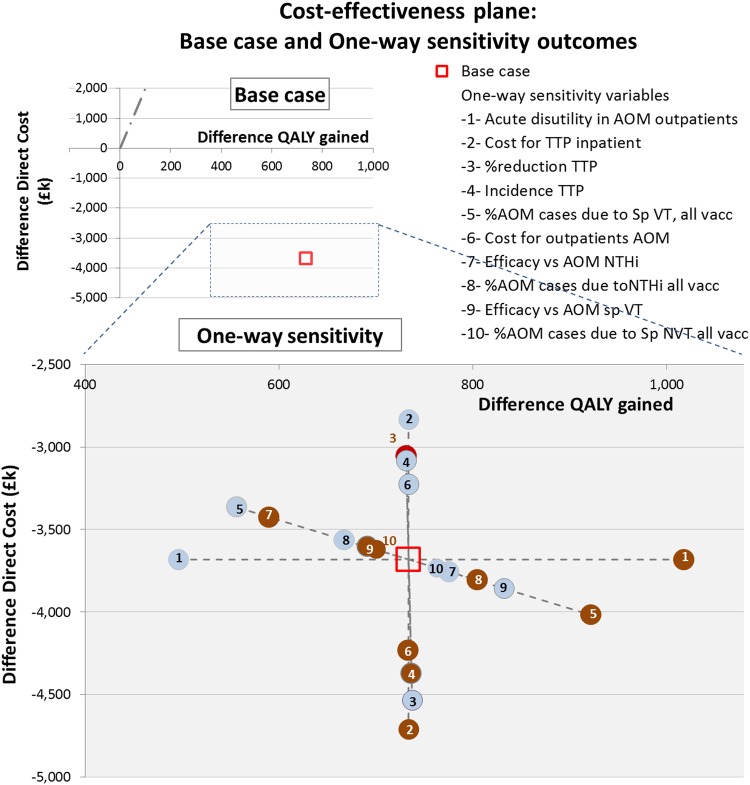

One-way sensitivity analyses showed that the model outcome (PHiD-CV dominated PCV-13) was robust to variations in model assumptions. Variables related to AOM (eg, disutility during an episode of AOM in outpatients, cost and reduction in TTP, AOM-related GP visits) were identified as key drivers of the cost-effectiveness results (see figure 2). The PSA showed that the model results were also robust to simultaneous variation of the parameters. The cost-acceptability curve estimated that PHiD-CV was more cost-effective compared with PCV-13 in 88% of simulations, with a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20 000/QALY (figure 3).

Figure 2.

One-way sensitivity analysis. Effect on the difference in QALY gained and on the difference in direct cost using the lower (light blue bullet) and upper bound value (brown bullet) of one parameter (-n-) and keeping all other parameters equal to the estimated value that is used for calculating the base case. Each parameter will provide two ICERs according its lower and upper bound (values in online supplementary table S1 in file 4). Parameter are ranked in descending order according to the spread between their two ICERs, with the highest spread referring to the most influencing parameter in the CEA analysis (acute disutility for AOM outpatient). AOM, acute otitis media; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; comparator=PHiD-CV, pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine; GP, general practitioner; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (=difference in direct cost divided by difference in QALY gained divided); NTHi, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; Sp, Streptococcus pneumonia; standard intervention=PCV-13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; VT, vaccine type.

Figure 3.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Probabilistic distributions have been defined around each parameter and 500 different parameter sets were sampled by varying all parameters simultaneously. The red point in the cost-effectiveness plane represents the base-case parameter set. QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Alternative scenarios

Table 3 reports the difference in total QALYs gained (discounted) and total costs (discounted) between the vaccines for a range of alternative scenarios. All scenarios showed more health benefits and cost-savings for PHiD-CV compared with PCV-13. Scenario 1, reducing net herd protection to 15% and 0%, did not affect the base-case results because both vaccines are affected equally. Scenario 2, accounting for the non-significant efficacy of 26% against serotype 3 for PCV-13, had only a small impact on the results (731 QALYs gained and £3.67 million saved with PHiD-CV vs PCV-13). Scenario 3, including NTHi ID/pneumonia (non-significant), would further increase the projected health benefits and associated savings provided by PHiD-CV (739 QALYs gained and £3.82 million saved with PHiD-CV vs PCV-13). Scenario 4, accounting for work days lost in addition to direct medical costs, increased the cost-savings to £5.13 million. Finally, Scenario 5 showed that accounting for the difference in list price between the two vaccines would result in cost-savings of £45.77 million.

Table 3.

Model outcomes from the scenario analyses

| PHiD-CV vs PCV-13 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Cost difference* (£) | QALY difference |

| Base case | −3 681 976 | 734 |

| No net herd protection | −3 681 967 | 734 |

| Serotype 3 efficacy against IPD=26% in PCV-13 | −3 669 466 | 731 |

| NTHi ID/pneumonia† included | −3 816 273 | 739 |

| Including productivity loss | −5 132 994 | 734 |

| Difference in list price‡ | −45 770 435 | 734 |

*Cost difference estimated on the basis of the number of consultations instead of episodes, using the RCGP 2011 weekly report data (from RCGP in England and Wales) and identical QALY gain assumed in deriving the associated ICER.

†Assumed incidence rate NTHi IPD 5% (expert opinion) and efficacy as in AOM; estimated incidence NTHi pneumonia cases 3% and percentage reduction in hospitalisation in accordance with efficacy in AOM.

‡In the UK, PCV-13 list price=£49.10 and PHiD-CV list price=£27.60.

AOM, acute otitis media; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ID, invasive disease; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; NTHi, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae; PCV-13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PHiD-CV, 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

Discussion

We evaluated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PHiD-CV vaccination in children compared with PCV-13 in the UK setting by updating a previously published Markov model.26 The present analysis showed a similar impact for both vaccines on the incidence of meningitis, bacteraemia and pneumonia. The main reasons for this finding include a low incidence of IPD, and new evidence indicating a lack of significant protection against serotype 3 for PCV-1317 and marked cross-protection provided by PHiD-CV against serotypes 6A and 19A.18 However, our model predicted substantially fewer cases of AOM for PHiD-CV compared with PCV-13. This would translate into considerable cost-savings and health benefits because of the high incidence of AOM. PHiD-CV was consistently shown to be dominant over PCV-13 (ie, PHiD-CV would provide more health benefits at a lower cost) in the sensitivity analyses (one-way and PSA) and alternative scenarios. The one-way sensitivity analysis also indicated that AOM-related model parameters were the primary drivers of cost-effectiveness results.

From an epidemiological perspective, declining IPD incidence may suggest that more emphasis should be placed on the control of AOM.

AOM constitutes the prime indication for antibiotic prescription in infants,20 21 hence pneumococcal vaccination by reducing the number of AOM cases could play a role in limiting the development of antibiotic resistance. In a cluster-randomised, double-blind trial, Palmu et al80 reported that the use of PHiD-CV vaccine in Finland could result in yearly 12 000 fewer outpatient antibiotic purchases for AOM in children aged <2 years. Assuming similar treatment practices in Finland and the UK, and accounting for the difference in number of AOM cases prevented between PHiD-CV and PCV-13 (161 918 AOM cases prevented) or no vaccination (423 339 AOM cases prevented), the extrapolation of the Finish results to the UK settings would translate into about 60 700 fewer antibiotic purchases per year in children aged <2 years between PHiD-CV and PCV-13. Conceptually, this updated model is identical to the previously published model evaluating the economic impact of PHiD-CV.26 The present model used updated parameters including recent epidemiological information (age-specific hospitalisation and GP consultation rates due to Sp meningitis, Sp bacteraemia, pneumonia and AOM including the incidence of inpatient TTP), recent VE data, cross-protection and evidence-based approximations of indirect protection. Furthermore, age-stratified serotype distribution for IPD could be constructed for 2013–2014 based on the recent data reported by Waight et al.51 Costs were indexed to 2014 values as appropriate and productivity loss was included in the scenario analysis. The baseline year of the updated model was 2013–2014, and accommodated the decline in the incidence of IPD seen in the UK since the introduction of PCV-7 in 2006 and subsequent implementation of PCV-13 in 2010. Against this epidemiological background, re-evaluation of the influence of vaccination strategies on disease incidence, costs, health gain and ICER is considered of interest.

While the cost-effectiveness profiles of different pneumococcal vaccination strategies in several countries have been previously evaluated using similar tools such as Markov cohort models, direct comparison of results is limited due to disparities in country-specific epidemiology and healthcare systems. Finally, static models such as ours integrate net herd protection (ie, herd protection and type replacement combined) as a fixed effect at equilibrium. However, dynamic models may be more appropriate to capture these effects over time and in relation to population characteristics and vaccine coverage.

Conclusions

When considering the cost-effectiveness of a 2+1 universal childhood vaccination programme in the UK from the perspective of medical costs, the strategy of using PHiD-CV dominates over use of PCV-13 when the vaccines are priced at parity. This result was primarily due to fewer AOM cases and associated cost-savings. Against the background of developing antibiotic resistance and reduced IPD incidence observed since the introduction of pneumococcal vaccination, our updated model suggests that deployment of the PHiD-CV vaccine would be of value in the UK. Finally, continuous active monitoring of epidemiological changes associated with pneumococcal vaccination programmes is important to inform future decision-making and healthcare policy in the UK.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jan Olbrecht (GSK Vaccines) for his support for the study and the publication, Fabien Debailleul (Business and Decision Life Sciences on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for publication coordination and Amrita Ostawal (freelancer on behalf of GSK vaccines) for medical writing assistance, and Carole Nadin (Fleetwith, on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for reviewing the manuscript for English usage.

Footnotes

Contributors: ED provided substantial scientific input to the study and study report, critically reviewed the study report, and was involved in study and economic modelling development, populating models and determination of model settings, acquisition of data, determination of the model inputs and statistical data analysis. OL provided substantial scientific input to the study and study report, critically reviewed the study report, and was involved in method selection and development, economic modelling development, data mining and literature review, populating models and determination of model settings, acquisition of data, model inputs and assessment of robustness of results (sensitivity analysis). ET participated in the selection of model inputs and the acquisition of data. NVdV provided substantial scientific input to the study and study report, critically reviewed the study report, was involved in the method selection, development and determination of model settings, and participated in the development of the economic modelling and the sensitivity analysis. All authors provided intellectual contributions to this manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Funding: GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this study and all costs associated with the development and the publishing of this present manuscript (internal GSK identifier: HO-12-8103).

Disclaimer: Synflorix is a trade mark of the GSK group of companies.

Competing interests: ED is an employee of the GSK group of companies and reports ownership of restricted shares from the GSK group of companies; OL reports that (A) he was an external consultant and received payment on a contract basis from the GSK group of companies at the time of the study and (B) is married to a previous employee of the GSK group of companies owning restricted shares from the GSK group of companies; ET is an employee of the GSK group of companies; NVdV is an employee of the GSK group of companies and reports ownership of restricted shares from the GSK group of companies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data used in this study are presented in the manuscript and the supplementary files, or references to the original material are provided. Please contact the corresponding author shall you require any additional information.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles. In: Atkinson W, Wolfe C, Hamborsky J, eds. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 12th edn Washington DC: Public Health Foundation, 2012:173–92. Public Health Foundation [12th Ed], 173-192. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Immunisation, Vaccines and Biologicals. Estimated Hib and pneumococcal deaths for children under 5 years of age 2008. http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/estimates/Pneumo_hib/en/ (accessed 27 Aug 2014).

- 3.Health Protection Agency. General Information on Pneumococcal Disease. http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1203008864027 (accessed 23 Nov 2015).

- 4.Public Health England. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/health-protection-agency (accessed 17 Sep 2014).

- 5.Elemraid MA, Sails AD, Thomas MF et al. Pneumococcal diagnosis and serotypes in childhood community-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;76:129–32. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falup-Pecurariu O. Lessons learnt after the introduction of the seven valent-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine toward broader spectrum conjugate vaccines. Biomed J 2012;35:450–6. 10.4103/2319-4170.104409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladhani SN, Slack MP, Andrews NJ et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease after routine pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in children, England and Wales. Emerging Infect Dis 2013;19:61–8. 10.3201/eid1901.120741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jokinen J, Palmu AA, Kilpi T. Acute otitis media replacement and recurrence in the Finnish otitis media vaccine trial. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:1673–6. 10.1093/cid/cis799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Services. The complete routine immunisation schedule 2013/14. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/227651/8515_DoH_Complete_Imm_schedule_A4_2013_09.pdf; (accessed 29 Aug 2014).

- 10.Prymula R, Peeters P, Chrobok V et al. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to protein D for prevention of acute otitis media caused by both Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typable Haemophilus influenzae: a randomised double-blind efficacy study. Lancet 2006;367:740–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68304-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domingues CM, Verani JR, Montenegro Renoiner EI et al. Effectiveness of ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in Brazil: a matched case-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:464–71. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70060-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tregnaghi MW, Sáez-Llorens X, López P et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal nontypable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) in young Latin American children: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001657 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitney CG, Pilishvili T, Farley MM et al. Effectiveness of seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease: a matched case-control study. Lancet 2006;368:1495–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69637-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deceuninck G, De Serres G, Boulianne N et al. Effectiveness of three pneumococcal conjugate vaccines to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease in Quebec, Canada. Vaccine 2015;33:2684–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jokinen J, Rinta-Kokko H, Siira L et al. Impact of ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in Finnish children--a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0120290 10.1371/journal.pone.0120290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.JCVI minutes Pneumococcal sub-committee meeting held on 30 May 2012. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120907090205/https://www.wp.dh.gov.uk/transparency/files/2012/07/JCVI-minutes-Pneumococcal-sub-committee-meeting-held-on-30-May-2012.pdf (accessed 28 Aug 2014).

- 17.Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Burbidge P et al. Serotype-specific effectiveness and correlates of protection for the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a postlicensure indirect cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:839–46. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70822-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Synflorix. Summary of Product Characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000973/WC500054346.pdf (accessed 29 Aug 2014).

- 19.Prevenar-13. http://www.pfizer.co.jp/pfizer/company/press/2013/documents/20131028_01.pdf (accessed 15 Aug 2014).

- 20.Dickson G. Acute otitis media. Prim Care 2014;41:11–18. 10.1016/j.pop.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wald ER. Acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(Suppl 4):S277–83. 10.1093/cid/cir042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cartwright K. Pneumococcal disease in western Europe: burden of disease, antibiotic resistance and management. Eur J Pediatr 2002;161:188–95. 10.1007/s00431-001-0907-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung IF, Tantawichien T, Tsai YH et al. Regional epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Asian adults: epidemiology, disease burden, serotype distribution, and antimicrobial resistance patterns and prevention. Int J Infect Dis 2013;17:364–73. 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelton SI, Huot H, Finkelstein JA et al. Emergence of 19A as virulent and multidrug resistant Pneumococcus in Massachusetts following universal immunization of infants with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26:468–72. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31803df9ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Eldere J, Slack MP, Ladhani S et al. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, an under-recognised pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:1281–92. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70734-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knerer G, Ismaila A, Pearce D. Health and economic impact of PHiD-CV in Canada and the UK: a Markov modelling exercise. J Med Econ 2012;15:61–76. 10.3111/13696998.2011.622323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office for National Statistics, UK National Life Tables, 1980–82 to 2011–13. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/datasets-and-tables/index.html (accessed 11 Jun 2015).

- 28.Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/population-estimates-for-uk--england-and-wales--scotland-and-northern-ireland/population-estimates-timeseries-1971-to-current-year/index.html (accessed 1 Apr 2015).

- 29.Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Primary diagnosis: 4 character, 2013–14. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB16722/hosp-outp-acti-2013-14-prim-diag-tab.xlsx (accessed 25 Sep 2015).

- 30.Pomeroy SL, Holmes SJ, Dodge PR et al. Seizures and other neurologic sequelae of bacterial meningitis in children. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1651–7. 10.1056/NEJM199012133232402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIntyre PB, Berkey CS, King SM et al. Dexamethasone as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials since 1988. JAMA 1997;278:925–31. 10.1001/jama.278.11.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kastenbauer S, Pfister HW. Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: spectrum of complications and prognostic factors in a series of 87 cases. Brain 2003;126:1015–25. 10.1093/brain/awg113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auburtin M, Porcher R, Bruneel F et al. Pneumococcal meningitis in the intensive care unit: prognostic factors of clinical outcome in a series of 80 cases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:713–17. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2105110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson AP, Waight P, Andrews N et al. Morbidity and mortality of pneumococcal meningitis and serotypes of causative strains prior to introduction of the 7-valent conjugant pneumococcal vaccine in England. J Infect 2007;55:394–9. 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melegaro A, Edmunds WJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in England and Wales. Vaccine 2004;22:4203–14. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royal College of General Practitioners. Research & Surveillance Centre Weekly Returns Service Annual Report 2011. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/research-and-surveillance-centre.aspx (accessed 17 Sep 2014).

- 37.Leibovitz E, Jacobs MR, Dagan R. Haemophilus influenzae: a significant pathogen in acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:1142–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausdorff WP, Yothers G, Dagan R et al. Multinational study of pneumococcal serotypes causing acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21:1008–16. 10.1097/01.inf.0000035588.98856.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Main procedures and interventions: 2013–14. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB16722/hosp-outp-acti-2013-14-main-proc-inte-tab.xlsx (accessed 25 Sep 2015).

- 40.Williamson I, Benge S, Mullee M et al. Consultations for middle ear disease, antibiotic prescribing and risk factors for reattendance: a case-linked cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:170–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Care Supply Association. Health Service Cost Index. https://nhsprocurement.org.uk/articles/health-service-cost-index (accessed 4 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2007, Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2007. http://http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/uc/uc2007/uc2007.pdf (accessed 28 Aug 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Public Health England. Vaccine uptake guidance and the latest coverage data. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/cover-of-vaccination-evaluated-rapidly-cover-programme-2014-to-2015-quarterly-data (accessed 11 Jun 2015).

- 44.Health Survey for England. 1996. http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/doh/survey96/tab5-29.htm (accessed 5 Nov 2007).

- 45.Bennett JE, Sumner W II, Downs SM et al. Parents’ utilities for outcomes of occult bacteremia. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng AK, Niparko JK. Cost-utility of the cochlear implant in adults: a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:1214–18. 10.1001/archotol.125.11.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh PI, Maerov P, Pritchard D et al. A cost-utility analysis of second-line antibiotics in the treatment of acute otitis media in children. Clin Ther 1996;18:160–82. 10.1016/S0149-2918(96)80188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrow A, De Wals P, Petit G et al. The burden of pneumococcal disease in the Canadian population before routine use of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2007;18:121–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oostenbrink R, Oostenbrink JB, Moons KG et al. Cost-utility analysis of patient care in children with meningeal signs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2002;18:485–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandran A, Herbert H, Misurski D et al. Long-term sequelae of childhood bacterial meningitis: an underappreciated problem. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:3–6. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ef25f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani SN et al. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:535–43. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70044-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller E, Andrews NJ, Waight PA et al. Effectiveness of the new serotypes in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine 2011;29:9127–31. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heffron R. Pneumonia: with special reference to pneumococcus lobar pneumonia. Commonwealth Fund, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kieninger DM, Kueper K, Steul K et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunologic noninferiority of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine given with routine pediatric vaccinations in Germany. Vaccine 2010;28:4192–203. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butler JC, Breiman RF, Campbell JF et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy. An evaluation of current recommendations. JAMA 1993;270:1826–31. 10.1001/jama.1993.03510150060030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singleton RJ, Butler JC, Bulkow LR et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease epidemiology and effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in Alaska native adults. Vaccine 2007;25:2288–95. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vesikari T, Wysocki J, Chevallier B et al. Immunogenicity of the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) compared to the licensed 7vCRM vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:S66–76. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318199f8ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Synflorix—Annex I—Summary of product characteristics (SmPC). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000973/WC500054346.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 59.European Medicines Agency. Science Medicines Health. Synflorix—Procedural steps taken and scientific information after the authoristation. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Procedural_steps_taken_and_scientific_information_after_authorisation/human/000973/WC500054350.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 60.Black SB, Shinefield HR, Ling S et al. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than five years of age for prevention of pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21:810–5. 10.1097/00006454-200209000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hansen J, Black S, Shinefield H et al. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than 5 years of age for prevention of pneumonia: updated analysis using World Health Organization standardized interpretation of chest radiographs. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:779–81. 10.1097/01.inf.0000232706.35674.2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madhi SA, Kuwanda L, Cutland C et al. The impact of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on the public health burden of pneumonia in HIV-infected and -uninfected children. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1511–8. 10.1086/429828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cutts FT, Zaman SM, Enwere G et al. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:1139–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lucero MG, Nohynek H, Williams G et al. Efficacy of an 11-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against radiologically confirmed pneumonia among children less than 2 years of age in the Philippines: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:455–62. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819637af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Afonso ET, Minamisava R, Bierrenbach AL et al. Effect of 10-valent pneumococcal vaccine on pneumonia among children, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:589–97. 10.3201/eid1904.121198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kury C. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine implemented in the municipality of Campos dos Goytacazes. Brazil: WSPID, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med 2001;344:403–9. 10.1056/NEJM200102083440602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fireman B, Black SB, Shinefield HR et al. Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:10–16. 10.1097/00006454-200301000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palmu AA, Verho J, Jokinen J et al. The seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine reduces tympanostomy tube placement in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:732–8. 10.1097/01.inf.0000133049.30299.5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palmu AA, Jokinen J, Borys D et al. Effectiveness of the ten-valent pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) against invasive pneumococcal disease: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381:214–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61854-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Wals P, Lefebvre B, Defay F et al. Invasive pneumococcal diseases in birth cohorts vaccinated with PCV-7 and/or PHiD-CV in the province of Quebec, Canada. Vaccine 2012;30:6416–20. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010;201:32–41. 10.1086/648593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1737–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa022823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feikin DR, Kagucia EW, Loo JD et al. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001517 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Public Health England. Pneumococcal disease infections caused by serotypes in Prevenar 13 and not in Prevenar 7. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pneumococcal-disease-caused-by-strains-in-prevenar-13-and-not-in-prevenar-7-vaccine/pneumococcal-disease-infections-caused-by-serotypes-in-prevenar-13-and-not-in-prevenar-7 (accessed 23 Nov 2015).

- 76.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Discounting of health benefits in special circumstances. http://www.nice.org.uk/media/955/4F/Clarification_to_section_5.6_of_the_Guide_to_Methods_of_Technology_Appraisals.pdf (accessed 8 Apr 2014).

- 77.Office for National Statistics, 2011 census, age by single year. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/search/index.html?newquery=QS103EW (accessed 28 Aug 2014).

- 78.Office for National Statistics, Statistical Bulletin, 2011 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (based on SOC 2010). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_256900.pdf (link to Excel file contained therein) (accessed 28 Aug 2014).

- 79.Department of Health. National tariff 2006/07: payment by results 2007. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4127649 (accessed 1 Apr 2014).

- 80.Palmu AA, Jokinen J, Nieminen H et al. Effect of pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) on outpatient antimicrobial purchases: a double-blind, cluster randomised phase 3-4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:205–12. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70338-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010776supp1.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010776supp2.pdf (20.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010776supp3.pdf (53.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010776supp4.pdf (109.5KB, pdf)