Abstract

Objectives

It is not currently clear whether all anticoagulated patients with a head injury should receive CT scanning or only those with evidence of traumatic brain injury (eg, loss of consciousness or amnesia). We aimed to determine the cost-effectiveness of CT for all compared with selective CT use for anticoagulated patients with a head injury.

Design

Decision-analysis modelling of data from a multicentre observational study.

Setting

33 emergency departments in England and Scotland.

Participants

3566 adults (aged ≥16 years) who had suffered blunt head injury, were taking warfarin and underwent selective CT scanning.

Main outcome measures

Estimated expected benefits in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were the entire cohort to receive a CT scan; estimated increased costs of CT and also the potential cost implications associated with patient survival and improved health. These values were used to estimate the cost per QALY of implementing a strategy of CT for all patients compared with observed practice based on guidelines recommending selective CT use.

Results

Of the 1420 of 3534 patients (40%) who did not receive a CT scan, 7 (0.5%) suffered a potentially avoidable head injury-related adverse outcome. If CT scanning had been performed in all patients, appropriate treatment could have gained 3.41 additional QALYs but would have incurred £193 149 additional treatment costs and £130 683 additional CT costs. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £94 895/QALY gained for unselective compared with selective CT use is markedly above the threshold of £20–30 000/QALY used by the UK National Institute for Care Excellence to determine cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

CT scanning for all anticoagulated patients with head injury is not cost-effective compared with selective use of CT scanning based on guidelines recommending scanning only for those with evidence of traumatic brain injury.

Trial registration number

Keywords: TRAUMA MANAGEMENT, Warfarin

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest study to model options for the clinical management of anticoagulated patients taking warfarin with a head injury.

The methods used to estimate health gain from treating additional cases detected by universal CT scanning are transparent and reproducible, and were robust to the sensitivity analyses undertaken.

Some patients who suffered adverse outcome may not have been identified on follow-up potentially being a limitation of the study, leading to underestimation of the potential benefit of CT scan for all patients.

Background

It is estimated that at least 1% of the UK population are taking an anticoagulant, such as warfarin, increasing to 8% in those aged 80 years and over.1 2 People taking an anticoagulant who experience a head injury are at an increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage,3 4 with rates of mortality reported between 45% and 70%.3 5–7 Liberal use of CT scanning is therefore required to identify intracranial haemorrhage in these patients. However, it is not clear whether all anticoagulated patients with head injury should receive a CT scan or whether CT should be used selectively and limited to those with evidence of traumatic brain injury, such as those with loss of consciousness or amnesia.8

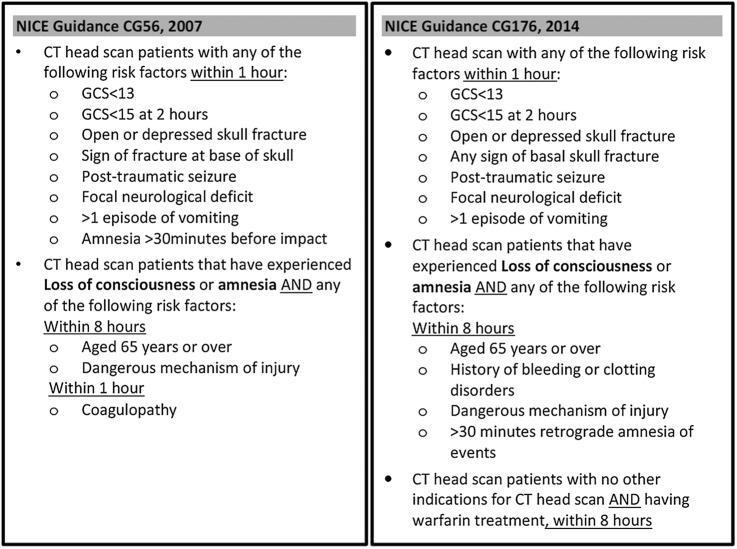

Management of head injury in the UK follows guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guidance issued in 20079 recommended that patients with coagulopathy (including those currently treated with warfarin) should undergo CT scanning only if they report amnesia or loss of consciousness following injury. Updated guidance issued in 201410 recommended that all patients having warfarin treatment should undergo CT scanning regardless of whether they reported amnesia or loss of consciousness (figure 1). The new guidance should increase the number of scans performed and intracranial injuries identified, but it is not clear whether the benefits of this approach justify the costs of additional CT scanning.

Figure 1.

NICE guidance 2007 versus 2014.

The AHEAD study was an observational cohort study of patients with head injury who were taking warfarin and presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) (S Mason, M Kuczawski, MD Teare, et al. The AHEAD study: an evaluation of the management of anticoagulated patients who suffer head injury. UK; 2016. Unpublished). It was undertaken when NICE 2007 guidance was in operation but before NICE 2014 guidance was issued. We aimed to use data from the AHEAD study and decision analysis modelling to determine the cost-effectiveness of CT for all compared with observed practice based on guidelines recommending selective CT for those with evidence of traumatic brain injury.

Methods

The methods for the AHEAD study are described in detail elsewhere (S Mason et al. 2016. Unpublished). Briefly, 3566 adults who were taking warfarin and attended the ED of 33 hospitals in England and Scotland between September 2011 and March 2013 following head injury were recruited. Research staff in hospital sites recorded basic demographic information, attendance details, injury mechanism, clinical examination findings and CT results. Patients were then followed up to 10 weeks after presentation using hospital record review and postal questionnaire.

We identified all patients with an adverse outcome who had not received a CT scan at their initial hospital attendance. The patients that did receive a CT scan (under a selective CT scanning policy) would receive the same treatment if a CT scan all policy was in place; therefore, it is the former group of patients who would be expected to receive clinical benefit from a policy of CT scanning all patients. However, a threshold analysis was conducted to estimate the proportion of inpatient attendances of <48 hours that would need to be avoided for the CT scan all policy to have a cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) below £30 000, assuming the cost of such an inpatient stay to be that associated with a non-elective inpatient stay (£615).11 An adverse outcome was defined as: death; neurosurgery; positive CT scan finding; or reattendance to the hospital with a significant head injury-related complication up to 10 weeks after the original attendance. These reattendances were confirmed following the review of hospital records and CT scan results, where undertaken.

Decision analysis modelling was used to estimate the incremental QALYs and costs had those patients with an adverse outcome that were not CT scanned received a CT scan on initial hospital attendance. Different assumptions were required for patients conditional on whether they survived the adverse event. For patients who died, assumptions were required regarding: the probability of survival if a CT scan had been performed; the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) state to which the patient would be categorised if they survived;12 and the cost of neurosurgery. For patients who survived, an assumption was required relating to the probability of GOS increase if a CT scan had been performed. Regardless of survival outcome, assumptions were required on: the life expectancy of a person with the same gender and age profile; the costs and utility associated with each GOS state; and the cost of a CT scan. The assumptions used within the model are detailed below. The results presented take an English and Scottish perspective and use direct healthcare and personal social services costs.

Model assumptions

For patients who did not survive the adverse event:

The probability of survival if a CT scan had been performed: Two clinicians provided estimates of the probability of survival had the patient received a CT scan. In the main analysis, an average value was used, although sensitivity analyses were undertaken, assuming that each clinician was correct.

The GOS state to which the patient would be categorised if they survived: A single clinician provided an estimate of the GOS of the patient if they had survived. In a sensitivity analysis, the impact of the GOS state being one level higher (ie, more favourable to the patient) was explored.

The costs of neurosurgery: The cost of neurosurgery was assumed to be that associated with the weighted average of NHS Reference Cost Codes AA50A–AA57B, excluding codes relating to patients aged 18 years and under, which was £3994.13 It was assumed that all patients who died without having a CT scan would undergo neurosurgery.

For patients who survived the adverse event:

The probability of GOS increase if a CT scan had been performed: Two clinicians provided estimates of the probability of an increase in the GOS level (ie, a better patient outcome), if a CT scan had been performed. In the main analysis, an average value was used, although sensitivity analyses were undertaken, assuming that each clinician was correct.

For all patients:

The life expectancy of the person: These data were taken from UK Life Tables,14 and it was assumed that these were not affected by an adverse event that had been survived.

The costs and utility associated with each GOS state: The data for GOS states 2–4 were taken from Pandor et al15 with costs inflated from 2008/2009 values to 2014/2015 prices using hospital and community health services indices reported in Curtis and Burns.11 The resultant values are provided in table 1. For GOS state 5, it was assumed that the UK general population utility conditional on age and sex was appropriate which was taken from Ara and Brazier.16

The cost of a CT scan: The cost of a CT scan was assumed to be that associated with NHS Reference Cost Code RD20A, which was £92.

The mathematical model: The model calculated the expected difference in costs and QALYs of moving from observed practice to a strategy of CT scanning all patients. The following formulae were used in calculating the cost and QALY impacts associated with provided CT scans to patients with adverse events who did not receive a CT scan. All values were discounted at 3.5% per annum in accordance with NICE guidelines.17 A lifetime horizon was assumed due to potential mortality benefits of the CT all strategy.

Table 1.

Assumed costs and utility associated with each Glasgow Outcome Scale state, and assumed cost of neurosurgery

| GOS state | One-off cost (£) | Annual costs (£) | Utility value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 47 674 | 46 595 | 0.00 | Pandor et al15 with costs inflated using Curtis and Burns11 |

| 3 | 0 | 37 214 | 0.15 | |

| 4 | 18 837 | 0 | 0.51 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | Population value* | Assumption |

*The utility in GOS state 5 were estimated from Ara and Brazier16 conditional on age and sex.

For patients who did not survive:

Change in costs: Average probability of survival if CT scan performed×(life expectancy×cost per year in estimated GOS state+cost of neurosurgery).

Change in QALYs: Average probability of survival if CT scan performed×(life expectancy×utility per year in estimated GOS state).

For patients who did survive:

Change in costs: Average probability of GOS increase if CT scan performed×life expectancy×(cost per year in higher GOS state–cost per year in lower GOS state).

Change in QALYs: Average probability of GOS increase if CT scan performed×(life expectancy×utility per year in higher GOS state–utility per year in lower GOS state)

Results

Follow-up data were available for 3534 of 3566 patients (99%) in the AHEAD cohort. Details of the cohort are published (S Mason et al. 2016. Unpublished). Glasgow Outcome Scale and diagnosis was available for 91.4% (n=3229) and 99.9% (n=3530) patients, respectively. Overall, 2114 out of 3534 patients (60%) received a CT scan. Of the 1420 patients without a CT scan, 728 (51%) were admitted to hospital, 20 (1.4%) had subsequent head injury-related hospital attendances and 74 (5.2%) died during follow-up. Cause of death was head injury-related in 4 (0.3%), unrelated in 52 (3.7%) and unknown in 19 (1.3%). Adverse outcomes were identified in 7 of 1420 (0.5%) patients who did not have CT scan: 4 deaths and 3 with a related further hospital attendance and significant finding on CT scan at reattendance.

The estimated changes in costs and QALYs per individual patient are provided in table 2. The summarised analyses including the increased costs of CT scans are provided in table 3.

Table 2.

Estimated outcomes for patients with adverse events who were not CT scanned if they had been CT scanned on admission to hospital and modelled implications for costs and quality-adjusted life years

| |

Outcomes |

Modelling |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Admitted | INR | Observed CT head scan | Reversal therapy | Neurosurgery | Further hospital attendance | HI death | Probability of survival (%) |

Estimated GOS if survived | Change in costs | Change in QALYs | ||

| Patient | Clinician 1 | Clinician 2 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 81 | M | ✗ | NP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 75 | 75 | 3 | £169 279 | 0.67 |

| 2 | 74 | M | ✗ | NP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 25 | 15 | 2 | £13 528 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 90 | M | ✗ | 4.4 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 0 | 0 | 2 | £3994 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 88 | M | ✗ | NP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 75 | 75 | 4 | £18 122 | 1.45 |

| Probability of GOS increase (+1, %) |

||||||||||||||

| Clinician 1 | Clinician 2 | Lower GOS score | ΔC | ΔQ | ||||||||||

| 5 | 76 | M | ✗ | 2.0 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 25 | 50 | 4 | −£7064 | 0.86 |

| 6 | 77 | F | ✗ | 3.0 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 25 | 0 | 4 | −£2355 | 0.27 |

| 7 | 82 | M | ✗ | 3.5 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 25 | 0 | 4 | −£2355 | 0.17 |

NP, not performed.

Table 3.

The comparison of CT all with observed practice

| Change in costs from CT scanning (£) | Change in QALYs from CT scanning | ICER (cost per QALY gained (£)) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in individual patient values | 193 149 | 3.41 | |

| Additional CT scanning costs | 130 683 | ||

| Net values | 323 832 | 3.41 | 94 895 |

It is estimated that the cost per QALY gained through providing a CT scan is in excess of £90 000 per QALY which is markedly greater than the £20 000–£30 000 per QALY gained threshold reported by NICE.17 This conclusion did not alter within the sensitivity analyses performed. Using the estimates from the individual expert clinicians which produced values of £90 659 and £99 547 per QALY gained or if the cost of neurosurgery was not included for the patient who neither expert clinician believed would have survived even with a CT scan (£93 725 per QALY gained). When it was assumed that all patients survived at one GOS state better than estimated in the base case, the cost per QALY gained reduced to £36 864 (an additional £213 139 to obtain 5.78 QALYs) but still did not fall below NICE thresholds.

It was estimated that over 67% of the 537 inpatient stays of <48 hours observed would need to be avoided in order for the CT scan all policy to have a cost per QALY of <£30 000.

Discussion

Follow-up of 1420 patients who did not have a CT scan in the AHEAD cohort identified seven cases (four deaths, three delayed diagnoses) that might have been identified by CT scanning at initial hospital attendance. Decision analytic modelling showed that appropriate treatment of these cases could have gained 3.41 QALYs but would have incurred £193 149 additional treatment costs and £130 683 additional costs for CT scanning. This produces an incremental cost of £94 895 per QALY gained, which is greatly above the usual threshold of £20–30 000/QALY that NICE uses to determine cost-effectiveness. Our analysis therefore suggests that CT for all anticoagulated patients with head injury, as recommended in NICE 2014 guidance, is not cost-effective compared with the selective use of CT scanning observed in practice when NICE 2007 guidance was in operation.

Our analysis has a number of strengths and weaknesses. It was based on a large representative cohort of patients who presented to a wide range of hospitals. The methods used to estimate health gain from treating additional cases detected by universal CT scanning are transparent and reproducible, and were robust to the sensitivity analyses undertaken. A potential limitation is that some patients who suffered adverse outcome may not have been identified on follow-up, leading to underestimation of the potential benefit of CT scan for all patients. However, it is worth noting that 10.79 QALYs would be required to reach the NICE threshold of £30 000/QALY for cost-effectiveness, so our conclusion regarding the lack of cost-effectiveness of unselective CT scanning would only be undermined if follow-up had identified <1 in 3 patients with adverse events. This seems extremely unlikely.

It is not believed that the threshold level for avoiding inpatient admissions of <48 hours would be plausible. Owing to the age and comorbidities of this cohort of patients, there will be many reasons for patients being admitted irrespective of whether a CT scan was performed. These reasons may be head injury-related such as observation, but are also likely to include other reasons such as intercurrent infections, injuries relating to attendance (other than the head injury) and for social reasons. Additionally, one could also postulate that by detecting incidental findings, the additional CT scans could result in additional admissions. If so, the incremental costs of the CT all strategy would increase and it would become less cost-effective. We have no data to determine whether additional CT scans result in more or fewer admissions.

Most international guidance, including the National Emergency X-Radiology Utilisation Study (NEXUS II), CT in Head Injury Patients (CHIP), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) head CT and the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS),18–21 advocate that all patients taking warfarin should have an immediate CT scan irrespective of injury severity, GCS or neurological symptoms. The UK guidelines (NICE) are based on the Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR),22 which excluded patients taking warfarin and up until January 2014, stated that a CT scan should be performed on patients taking warfarin if the patient presented with loss of consciousness or amnesia. These guidelines have now been updated to recommend all anticoagulated patients receive a CT scan, but no new evidence appears to have been published to support this recommended change in practice. Our analysis suggests that the 2014 revision to NICE guidance has resulted in less cost-effective care.

Previous literature investigating the patient outcomes and costs associated with diagnosing and treating head-injured patients who are taking anticoagulants are limited and difficult to compare with our analysis. Several recent studies have used decision analysis modelling to estimate the costs and benefits of CT scanning in the general (ie, non-anticoagulated) head-injured population23–25 and have generally shown that using a clinical decision rule to select patients for CT scanning is more cost-effective than unselective CT scanning. The only study identified that focused solely on anticoagulated patients was undertaken by Li in 2012.26 Li questioned how this cohort of patients should be managed due to the nature of delayed complications associated with anticoagulant use, while also considering the costs attached to CT imaging and admittance to hospital. The analyses were based on data taken from other studies and included repeated CT scans (2) and 24-hour admission per patient. The costs per year of a life saved in the USA, Spain and Canada were estimated as $1 million, $158 000 and $105 000, respectively.

Future research is needed to validate our findings on the potential benefits, harms and costs of CT scanning since the introduction of NICE 2014, in addition to further work on the criteria used for deciding whether a CT scan is appropriate such as the use of serum protein biomarkers.

Conclusion

CT scanning for all anticoagulated patients with head injury is not cost-effective compared with selective use of CT scanning based on guidelines recommending scanning only for those with evidence of traumatic brain injury. A move (or return) to selective use of CT scanning would substantially reduce healthcare costs with only a small increase in potentially avoidable adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rosemary Harper for her contribution as a patient representative throughout the duration of the study; all the clinicians and research staff in the participating hospital sites who identified patients in this study, without whose hard work, this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors provided substantial contributions to the conception, design, acquisition of the data, or analysis and interpretation of the study data. MK drafted the article and all authors contributed to its revision for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version. SM is the guarantor. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to accuracy or integrity of any party of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme grant reference number PB-PG-0808-17148. This work is sponsored by Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, reference number STH15705.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: NRES Committee Yorkshire and The Humber—Sheffield: 11/H1308/13.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kamali F, Pirmohamed M. The future prospects of pharmacogenetics in oral anticoagulation therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;61:746–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02679.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadelius M, Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin: current status and future challenges. Pharmacogenomics J 2007;7:99–111. 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volans AP. The risks of minor head injury in the warfarinised patient. J Accid Emerg Med 1998;15:159–61. 10.1136/emj.15.3.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart RG, Boop BS, Anderson DC. Oral anticoagulants and intracranial hemorrhage. Facts and hypotheses. Stroke 1995;26:1471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hylek EM, Singer DE. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in outpatients taking warfarin. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:897–902. 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrera PC, Bartfield JM. Outcomes of anticoagulated trauma patients. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:154–6. 10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathiesen T, Benediktsdottir K, Johnsson H et al. . Intracranial traumatic and non-traumatic haemorrhagic complications of warfarin treatment. Acta Neurol Scand 1995;91:208–14. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leiblich A, Mason S. Emergency management of minor head injury in anticoagulated patients. Emerg Med J 2011;28:115–8. 10.1136/emj.2009.079442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. (Clinical Guideline 56.) London 2007. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG56

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. (Clinical Guideline 176.) London 2014. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG176

- 11.Curtis L, Burns A. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2015. Canterbury, Kent: Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2015. (accessed Jan 2016). http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JTL, Pettigrew LEL, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma 1998;15:573–85. 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health. National Schedule of Reference Costs 2014–15 for NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts. London: 2015. (accessed Jan 2016). http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2014-to-2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics. National Life Tables, 2010–2012. London: 2014. (accessed Jan 2016). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-352834. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandor A, Goodacre S, Harnan S et al. . Diagnostic management strategies for adults and children with minor head injury: a systematic review and an economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–202. 10.3310/hta15270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ara R, Brazier JE. Populating an economic model with health state utility values: moving toward better practice. Value Health 2010;13:509–18. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisals. London: 2013. (accessed Jan 2016). http://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mower WR, Hoffman JR, Herbert M et al. . Developing a clinical decision instrument to rule out intracranial injuries in patients with minor head trauma: methodology of the NEXUS II investigation. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:505–14. 10.1067/mem.2002.129245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smits M, Diederik W, Dippel W et al. . Predicting intracranial traumatic findings on computed tomography in patients with minor head injury: the CHIP prediction rule. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:397–405. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ Jr et al. . Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:714–48. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vos PE, Battistin L, Girbamer G et al. . EFNS guideline on mild traumatic brain injury: report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2002;9:207–19. 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K et al. . The Canadian CT head rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet 2001;357:1391–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04561-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnick ER, Keegan J, Taylor RA. Redefining overuse to include costs: a decision analysis for computed tomography in minor head injury. J Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2015;41:313–22. 10.1016/S1553-7250(15)41041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits M, Dippel DW, Nederkoorn PJ et al. . Minor head injury: CT-based strategies for management—a cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology 2010;254:532–40. 10.1148/radiol.2541081672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes MW, Goodacre S, Stevenson MD et al. . The cost-effectiveness of diagnostic management strategies for adults with minor head injury. Injury 2012;43:1423–31. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J. Admit all anticoagulated head-injured patients? A million dollars versus your dime. You make the call. Ann Emerg Med 2012;59:457–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]