Abstract

Objective

To develop an inclusive model of culturally sensitive support, using a specialist dementia nurse (SDN), to assist people with dementia from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities and their carers to overcome barriers to accessing health and social care services.

Design

Co-creation and participatory action research, based on reflection, data collection, interaction and feedback from participants and stakeholders.

Setting

An SDN support model embedded within a home nursing service in Melbourne, Australia was implemented between October 2013 and October 2015.

Participants

People experiencing memory loss or with a diagnosis of dementia from CALD backgrounds and their carers and family living in the community setting and expert stakeholders.

Data collection and analysis

Reflections from the SDN on interactions with participants and expert stakeholder opinion informed the CALD dementia support model and pathway.

Results

Interaction with 62 people living with memory loss or dementia from CALD backgrounds, carers or family members receiving support from the SDN and feedback from 13 expert stakeholders from community aged-care services, consumer advocacy organisations and ethnic community group representatives informed the development and refinement of the CALD dementia model of care and pathway. We delineate the three components of the ‘SDN’ model: the organisational support; a description of the role; and the competencies needed. Additionally, we provide an accompanying pathway for use by health professionals delivering care to consumers with dementia from CALD backgrounds.

Conclusions

Our culturally sensitive model of dementia care and accompanying pathway allows for the tailoring of health and social support to assist people from CALD backgrounds, their carers and families to adjust to living with memory loss and remain living in the community as long as possible. The model and accompanying pathway also have the potential to be rolled out nationally for use by health professionals across a variety of health services.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A co-design approach, using feedback from people with dementia, their carers and families and experts in the field, was used to influence the development of a model of support for people experiencing memory loss or with dementia from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds and their carers and families living in the community, to ensure that it addressed their needs.

We outline the resources required for an organisation to provide culturally sensitive dementia care, what the specific role of the specialist dementia nurse involves and the attributes and skills required to fulfil the role.

We also provide a detailed CALD dementia pathway quick reference guide for health professionals.

Despite the development of a CALD model of dementia support and pathway barriers to culturally appropriate home support services and planned activity groups meant that in some cases available services and activities were not always compatible with need.

While this in-depth qualitative study led to the development of a model of support for people experiencing memory loss or with dementia from CALD backgrounds, in order to provide a strong evidence base we recommend that our model be further tested by a wider scale evaluation using a randomised controlled trial design.

Background

With a rapidly ageing Australian population and a strong preference for older Australians to remain living in their own homes for as long as possible, the development of strong systems of support for all community members is vital.1 In 2011, it was estimated that there were ∼200 000 informal carers of people with dementia, in Australia, living in the community.2 In recognition of the need to relieve the burden on carers, both federal and state governments provide Home and Community Care (HACC) services to assist with the activities of daily living (ADLs). ADLs can be described as bathing, eating, shopping, toileting, home medication management and home maintenance.3

Despite the existence of these services, however, there is often a failure to access them.4 In 2014, Phillipson et al5 reported that despite formal community-based services being available, the use of these services by carers is quite low. In the case of respite, this was attributed to the services not meeting the carer's or care recipient's needs or the belief that the service would result in negative outcomes.5 People from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities are particularly at risk of not using services due to the numerous barriers they face accessing healthcare services.6 Often, this is due to difficulties with language, with ∼16% of the Australian population speaking a language other than English at home,6 and a lack of knowledge of healthcare service systems. Currently, in Australia, there are limited language-specific and culture-specific supports for people with dementia and their carers and a shortage of culturally appropriate assessments.7 This deficit is a major impediment to the accurate diagnosis and treatment of dementia; consequently, diagnosis of dementia in CALD communities often occurs in the later stages of the disease as first contact with health professionals most often happens at crisis point.4 8 Factors that have been identified as impacting on early detection of dementia in older people from Asian backgrounds, in addition to a lack of CALD appropriate diagnosis tools and services, include the level of dementia literacy, symptom interpretation and dementia-related stigma.9 It has been also been purported that health services need to consider language, religious belief and observance, cultural practices (including food handling and personal care practices), social support and coping mechanisms during service provision.10 Studies have also found that perceived cultural sensitivity in relation to healthcare leads to greater satisfaction with healthcare providers and also influences adherence to treatment and better health outcomes.4

Models of support using a ‘support worker’ have been developed and implemented both in Australia and overseas to assist people and their carers to adjust to living with memory loss and functional decline.11 12 Support workers are workers who are usually skilled in assessment and able to provide ongoing support to someone with a cognitive impairment and their families and carers. The support worker role also provides assistance with navigation of the health and aged-care system, accessing of services, information and support, and advocating between health professionals, services and service users.11 12 However, few support worker models address the needs of those from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities.12

Culturally sensitive healthcare has previously been described as ‘the ability to be appropriately responsive to the attitudes, feelings, or circumstances of groups that share a common and distinctive racial, national, religious, linguistic or cultural heritage’13 in a manner that is relevant to clients' needs and their expectations.14 This project aimed to establish and refine a culturally sensitive model of dementia support and accompanying pathway through the implementation of a specialist dementia nurse (SDN) role to act as an advocate, navigator and strategist for the culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) person with cognitive impairment living in the community and their family or carer and most at risk of adverse dementia outcomes.

Methods

We developed an inclusive model of consumer-directed community-based dementia care and a dementia care pathway (figures 1 and 2) that uses culturally appropriate assessment tools15 and reaches individuals, the family and carers from CALD backgrounds.

Figure 1.

Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) specialist dementia nurse model.

Figure 2.

Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) dementia care pathway. See Supplementary file for the full set of reference cards.

Study design

Theoretical framework

Our qualitative study used a co-creation and participatory action research (PAR) approach.16 PAR is an approach to research that includes the involvement of the community that is being researched in order to understand their world and to ensure that research outcomes are appropriate to identified needs.16 The increasing move to redesign healthcare systems around patients' needs influenced the choice to use a co-creation and participatory action approach to developing an effective clinical model of support and pathway based on patients' experiences and expert stakeholder opinion.17 18 PAR in this instance was based on reflection, data collection, interaction with participants and feedback from stakeholders in a cyclical manner throughout the duration of the study.16

Participant and stakeholder selection

Stakeholders representing clinical and community aged-care services (Senior Clinical Dementia Nurses, Occupational Therapist/Manager—Cognitive Decline Memory Clinic, Home Nursing Service Site Managers, Aged Care Assessors, Diversity) government, consumer advocacy and ethnic community groups were selected purposively to ensure the inclusion of adequate expertise in the delivery of high-quality dementia care and CALD appropriateness. People from CALD backgrounds, experiencing difficulties with memory loss or with a formal diagnosis of dementia, over 65 years of age who were living in the community, and their families and carers were eligible. Community nurses providing care to people with dementia from CALD backgrounds made referrals to the SDN and details of the service were also disseminated through other health services, ethnic communities, local government, radio announcements and advertisements that were placed in ethnic-specific newsletters. Information about the service was also made available when presenting the study at dementia-related conferences. Participants who were unable to speak English were not excluded from the study and interpreters were made available to anyone who needed this service. People with cognitive impairment undergoing palliative care or experiencing psychiatric issues that the SDN identified as impacting on their ability to provide consent were excluded. The SDN used a capacity checklist together with expert knowledge and assessment skills to determine the ability to consent to participation.

Settings

The SDN role was embedded within a not-for-profit home nursing service that provides support to a large number of community-dwelling people with cognitive impairment from CALD backgrounds in Melbourne, Victoria. The SDN was integrated into normal services and was available for all clients from a CALD background experiencing memory problems or dementia and/or their carers and family members. The programme was not, however, limited to the organisations' clients and anyone fitting the criteria was able to access it. The intervention was conducted over a 2-year period between October 2013 and October 2015.

Data collection and analysis

Assessment and care planning

The SDN undertook assessment and care planning activities with each participant in line with the usual home nursing service current best practice model. The SDN also recorded case notes, describing interactions with each participant and using reflective practice methods19 to document experiences and observations following each client visit.

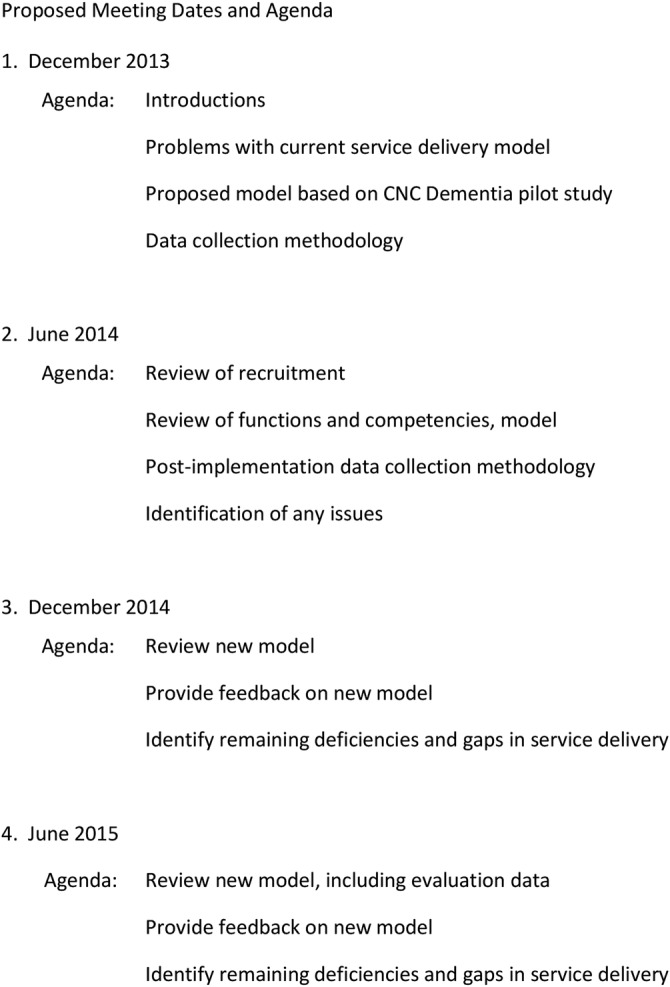

Expert reference group meetings

The expert stakeholder reference group members met together with the research team on four occasions throughout the duration of the study. Initially, to contribute to a proposed model of dementia care that would address current service delivery gaps, review functions and establish competencies and then thereafter to provide feedback on the implementation of the new model, identify any remaining gaps in service delivery and contribute to the CALD dementia pathway (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Advisory group dates and agenda. CNC, Clinical Nurse Consultant.

The SDN reflections and case note data were presented to the expert stakeholders for discussion at each reference group meeting. The SDN and the research team worked closely with members of the expert reference group throughout the study to develop and refine the CALD dementia care model and accompanying pathway quick reference cards (see figures 1 and 2).

Results

Participants

Thirteen stakeholders representing the community aged-care services, government, consumers, consumer advocacy and ethnic community groups were engaged as members of an expert reference group.

Sixty-two people (41 female, 21 male) received support from the SDN. The average age of participants was 69±14 years. The majority of participants (n=36/62) were people from CALD backgrounds living with dementia or memory loss. Fifteen were family members and 11 identified themselves as carers (table 1). Fourteen participants were from Italian backgrounds. Other ethnicities were Maltese (n=8), Vietnamese (n=7), Turkish (n=7), Greek (n=6), German (n=6), Burmese (n=4), Chinese (n=3), Iraqi (n=2), Dutch (n=2), Australian (n=2), Hungarian (n=1) and Nepalese (n=1) (see table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, number of interactions and interventions

| Client | Age | Gender | Ethnicity | Participant type | Number of interactions | Brochures | Forward planning | Local council—hygiene assistance | Local council—domestic assistance | Alzheimer's Australia | Carers Victoria | Respite services | Music therapy | Planned activity group | DBMAS | ACAS | CDAMS/geriatrician | SDN in-home strategies | Centrelink |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | Female | Italian | Family | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 2 | 43 | Male | Iraqi | Family | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 3 | 44 | Female | Maltese | Family | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 4 | 46 | Female | Italian | Carer | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | 46 | Female | Vietnamese | Carer | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 6 | 47 | Female | Turkish | Family | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 7 | 48 | Female | Italian | Family | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 8 | 48 | Female | Maltese | Family | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 9 | 51 | Female | Burmese | Family | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 10 | 52 | Female | Maltese | Family | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 11 | 52 | Male | Maltese | Family | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 12 | 53 | Female | Greek | Family | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 13 | 53 | Female | Italian | Carer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 14 | 54 | Female | German | Family | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 15 | 57 | Female | Greek | Carer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 16 | 61 | Female | Turkish | Family | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 17 | 61 | Male | Turkish | Family | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 18 | 62 | Female | Italian | Carer | 48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 19 | 65 | Female | Burmese | Consumer | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 20 | 65 | Male | Vietnamese | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 21 | 66 | Male | Italian | Consumer | 47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 22 | 66 | Female | Iraqi | Consumer | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 23 | 66 | Male | Australian | Family | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 24 | 69 | Female | German | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 25 | 70 | Male | German | Family | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 26 | 72 | Female | Italian | Carer | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 27 | 72 | Female | German | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 28 | 72 | Female | Dutch | Consumer | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 29 | 72 | Female | Maltese | Consumer | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 30 | 72 | Male | Italian | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 31 | 73 | Male | Hungarian | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 32 | 73 | Female | Maltese | Carer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 33 | 74 | Female | Chinese | Consumer | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 34 | 75 | Female | Vietnamese | Carer | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 35 | 75 | Female | Australian | Carer | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 36 | 76 | Male | Maltese | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 37 | 77 | Female | Burmese | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 38 | 78 | Female | Italian | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 39 | 78 | Male | Italian | Consumer | 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 40 | 78 | Male | German | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| 41 | 78 | Male | Dutch | Consumer | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 42 | 78 | Male | Maltese | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 43 | 78 | Female | Nepalese | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 44 | 80 | Female | Greek | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 45 | 80 | Male | Burmese | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 46 | 80 | Female | Turkish | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 47 | 81 | Female | Italian | Consumer | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 48 | 81 | Female | Chinese | Carer | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 49 | 81 | Female | Vietnamese | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 50 | 82 | Male | Italian | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 51 | 82 | Female | Vietnamese | Consumer | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 52 | 83 | Male | Greek | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 53 | 83 | Female | Italian | Carer | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 54 | 84 | Female | German | Consumer | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 55 | 84 | Male | Italian | Consumer | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 56 | 84 | Female | Vietnamese | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 57 | 84 | Male | Turkish | Consumer | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 58 | 85 | Female | Greek | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 59 | 87 | Male | Chinese | Consumer | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 60 | 87 | Female | Turkish | Consumer | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 61 | 88 | Female | Greek | Consumer | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| 62 | 88 | Male | Vietnamese | Consumer | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Total | 62 | 21 | 5 | 5 | 33 | 25 | 14 | 6 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 34 | 5 |

Centrelink—Access to financial assistance/carer payment.

ACAS, Aged Care Assessment Service; CDAMS, Cognitive Decline and Memory Services; DBMAS, Dementia Behaviour Management Advisory Service; SDN, specialist dementia nurse.

SDN assessment and care plan: reflections on the type and frequency of support needed

The SDN identified that many participants lacked the confidence or knowledge to overcome barriers or may have had bad experiences in the past when accessing healthcare services and recognised that advocating for the client, their family and carers was paramount to the success of them achieving their goals and enabling them to live well at home. The SDN implemented a variety of interventions tailored to meet individual needs of CALD consumers. Interventions included: brochures translated into their own language; information on forward planning; accessing local council home care and personal hygiene services; incontinence advice; referral to consumer and carer advocacy groups; community assessment services; behavioural management services; music therapy; assistance in accessing financial reimbursements; aids and assistive technology. While all participants were provided with information brochures in their own language, 33 participants were provided referrals to Alzheimer's Australia Victoria and 25 to Carers Victoria for further information. The SDN provided in-home strategies or advice to 34 participants including advice on incontinence and resolving unmet needs. The overall number of interactions between the SDN and the 62 participants was 406 (see table 1 for details on interventions and interactions). Interactions consisted of a combination of face-to-face visits and telephone contact. Support from the SDN was provided on an ‘as needs-based service’ and participants could step in and out of the service as required. There was no time or length of service restrictions. No participants exited the service due to dissatisfaction or their needs not being met.

Components of the SDN model

The SDN and the expert stakeholders identified an overarching framework and three components of the SDN model based on analysis of case notes and the SDN's self-reflections, as being required to facilitate the implementation of a culturally sensitive SDN model. The framework consists of culturally appropriate assessments, referral and linking; a diversity framework with guidelines, policies and education and understanding and acceptance of difference cultures.20

The three components of the model that were identified are: organisational support needed, the detail of the support worker role and the competencies required to undertake the role, that is, attributes, skills and knowledge (see figure 1). Each component of the model is discussed in turn below.

Organisational support required to support the SDN model?

Resources required to support the implementation of the SDN model for CALD communities include access to office space, a mobile telephone, a computer, a dedicated vehicle and interpreters. Facilitation of access to specialised services and other organisations with expert dementia knowledge and skills, ongoing professional development and education opportunities, including attendance at conferences, seminars and relevant education, is also essential as is the availability of debriefing and counselling (see figure 1).

What does the SDN role entail?

The SDN role needs to have sufficient autonomy and flexibility to allow for the tailoring of support to assist people from CALD backgrounds, their carers and families. The SDN provides assistance to navigate the aged and healthcare service systems, as well as culturally appropriate information to assist people with dementia and their caring unit to adjust to living with memory loss by increasing their understanding of dementia and the need for forward care planning, identify unmet needs and provide in-home strategies to manage change in behaviour to improve the quality of life of people with dementia and reduce carer strain, obtain culturally appropriate assessment and diagnosis and act as an advocate when necessary (see figure 1).

What knowledge, skills and attributes does an SDN need?

Implementation of the SDN role revealed that in order to meet the needs of consumers and provide person-centred care, the SDN role required the ability to build trusting professional relationships, excellent assessment abilities, an in-depth knowledge of dementia, excellent interpersonal, listening and advocacy skills, and an acceptance and understanding of different cultures and strong leadership skills (see figure 1).

Development of the CALD dementia care pathway

A set of quick reference cards, to be used in conjunction with a consumer-directed care approach to care and based on the SDN model, was designed to be used as a point of reference for health professionals undertaking a support worker type role in CALD communities (see figure 2).

The CALD dementia care pathway quick reference cards provide an outline of steps to consider prior to meeting with the client, engaging with the client, taking the client's history in a culturally appropriate manner, culturally appropriate assessment tools, goal setting and care planning, monitoring and review, exit planning, details of the diversity model and where to find further information, support and resources (see figure 2).

Discussion

This study delineates a framework for providing support to people with dementia from CALD backgrounds and their families and carers. The inclusion of consumers and expert stakeholders in the co-creation of a culturally sensitive model of dementia support and accompanying pathway has provided a means by which to appropriately respond to the attitudes, feelings and circumstances that are relevant to client needs and expectations and address the inequities currently faced by CALD communities.

The effectiveness of our person-centred inclusive model of community-based health and social care for CALD communities was demonstrated by the uptake of numerous community support services including aged-care assessments, planned activity groups and respite care, an area previously reported as having low uptake.5

Additionally, our model of support developed for people with dementia from CALD backgrounds and their families and carers is innovative. A systematic review of support worker interventions for people with dementia and/or their carers, undertaken by the study authors, revealed that out of 36 models of support for people with dementia and/or their carers, only 4 were provided to people from CALD backgrounds.12 Since three of the four models identified provided support to Chinese people with dementia and/or their caregivers living in Hong Kong, they cannot be considered as culturally or linguistically diverse models of care.21–23 Therefore, only one of the papers, by Boughtwood et al,24 actually reported on a CALD model of support for people with dementia and their families/caregivers living in the community setting in Australia. This model, however, focused on the experiences and perceptions regarding workers’ perspectives on the dynamics and management of family caregiving for dementia in CALD communities and how this influenced decisions made about family caregiving. Three main themes: cultural and familial norms pertaining to illness and older people; understanding and naming the term carer; and patterns in family caregiving were identified.24 A number of subthemes were also identified; these included: keeping dementia in the family; being judged by the community; women as carers; children carers; spousal carers and family sharing care, which demonstrated the expectations that elderly people would be cared for by one or more family members.24

Our novel model of dementia support provides a significant contribution to the literature as it is the first such model specifically developed for people with dementia from CALD backgrounds living in the community setting. The accompanying CALD Dementia Care Pathways quick reference cards also provide a valuable reference for health professionals providing care to people with dementia from CALD backgrounds.

Conclusions

The SDN model of care and CALD dementia care pathway addresses current healthcare system service gaps by providing culturally and linguistically diverse communities with health and social care services that are culturally appropriate. There is potential for this consumer-directed model to improve the well-being of persons with dementia and their carers and family members from minority, vulnerable groups and assist them to adjust to living with memory loss. Embedding this person-centred culturally appropriate model of care into health services nationally would provide equitable access to vital services that enables CALD community members across Australia to remain living at home as long as possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of participants, all members of the expert reference group and Senior Dementia Advisor Ms Fleur O'Keefe.

Footnotes

Contributors: DG and SK conceived and initiated the study. JK undertook the role of the specialist dementia nurse. DG and JK undertook the data collection. DG, JK and SK undertook the data analysis and the final drafting of the article and revised it for critical content, approved the final version of the paper and accept accountability for all aspects of the work. JK and DG developed and refined the CALD Dementia Care Pathway.

Funding: Funding for this project was proudly provided by the Lord Mayors Charitable Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Royal District Nursing Service Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.KPMG. Dementia service pathways: an essential guide to effective service planning. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2012. Dementia in Australia. Cat. no. AGE 70. Canberra: AIHW, 2012.

- 3.Victorian HACC Active Service Model: discussion paper. Victoria, Australia: Department of Human Services (DHS), 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenwood N, Habibi R, Smith R et al. . Barriers to access and minority ethnic carers’ satisfaction with social care services in the community: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Health Soc Care Community 2015;23:64–78. 10.1111/hsc.12116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillipson L, Jones SC, Magee C. A review of the factors associated with the non-use of respite services by carers of people with dementia: implications for policy and practice. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:1–12. 10.1111/hsc.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radermacher H, Feldman S, Browning C. Mainstream versus ethno-specific community aged care services: it's not an ‘either or’. Australas J Ageing 2009;28:58–63. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leone D, Carragher N, Santalucia Y et al. . A pilot of an intervention delivered to Chines and Spanish speaking carers of people with dementia in Australia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2014;29:32–7. doi:10.11771533317513505130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perceptions of Dementia in Ethnic Communities. https://fightdementia.org.au/sites/default/files/20101201-Nat-CALD-Perceptions-of-dementia-in-ethnic-communities-Oct08.pdf Alzheimers Australia Report, 2008. (accessed May 2016).

- 9.Lee S, Lin X, Haralambous B et al. . Factors impacting on early detection of dementia in older people of Asian background in primary healthcare. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 2011;3:120–7. 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2011.00130.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iliffe S, Manthorpe J. The debate on ethnicity and dementia: from category fallacy to person centred care. Aging Ment Health 2004;8:283–92. 10.1080/13607860410001709656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manthorpe J, Martineau S, Moriarty J. Support workers in social care in England: a scoping study. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:316–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goeman D, Renehan E, Koch S. What is the effectiveness of the support worker role for people with dementia and their carers? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:285 10.1186/s12913-016-1531-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker CM, Marsiske M, Rice KG et al. . Patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: model testing and refinement. Health Psychol 2011;30:342–50. 10.1037/a0022967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumdar B, Browne G, Roberts J et al. . Effects of cultural sensitivity training on health care provider attitudes and patient outcomes. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36:161–6. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storey J, Rowland J, Basic D et al. . The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): a multicultural cognitive assessment scale. Int Psychogeriatr 2004;16:13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer J. Action Research. In: Pope C, Mays N, eds. Qualitative research in health care. 3rd edn MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006:121–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friere K, Sangiorgi D. Service design and healthcare innovation: from consumption to co-production and co-creation. Proceedings of the 2nd Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation 2010 Dec1-3, Linköping, Sweden: http://www.servdes.org/pdf/2010/freire-sangiorgi.pdf (accessed May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson CL, Janamian T, Booth M et al. . Creating health care value together: a means to an important end. Med J Aust 2016;204:S3–4. 10.5694/mja16.00122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulman C, Schutz S. Reflective practice in nursing practice. 4th edn Chichester: Blackwell Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michael J. Diversity conceptual model for aged care: person-centred, difference-oriented and connective with a focus on benefit, disadvantage and equity. Australas J Ageing 2016;35:210–15. 10.1111/ajag.12313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chien WT, Lee YM. A disease management program for families in Hong Kong with dementia. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:433–6. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chien W, Lee Y. Randomised controlled trial of a dementia programme for families of home-resided older people with dementia. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:774–87. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam LC, Lee JS, Chung JC et al. . A randomised controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of case management model for community dwelling older persons with mild dementia in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:395–402. 10.1002/gps.2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boughtwood D, Shanley C, Adams J et al. . Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) families dealing with dementia: an examination of the experiences and perceptions of multicultural community link workers. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2011;26:365–77. 10.1007/s10823-011-9155-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]