Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and whether NCDs were treated or not, among hospitalised decontamination workers who moved to radio-contaminated areas after Japan's 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster.

Methods

We retrospectively extracted records of decontamination workers admitted to Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital between 1 June 2012 and 31 August 2015, from hospital records. We investigated the incidence of underlying NCDs such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes among the decontamination workers, and their treatment status, in addition to the reasons for their hospital admission.

Results

A total of 113 decontamination workers were admitted to the hospital (112 male patients, median age of 54 years (age range: 18–69 years)). In terms of the demographics of underlying NCDs in this population, 57 of 72 hypertensive patients (79.2%), 37 of 45 dyslipidaemic patients (82.2%) and 18 of 27 hyperglycaemic patients (66.7%) had not been treated for their NCDs before admission to the hospital.

Conclusions

A high burden of underlying NCDs was found in hospitalised decontamination workers in Fukushima. Managing underlying diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus is essential among this population.

Keywords: OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH, SOCIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data were only assessed for hospitalised decontamination workers, which may have led to an overestimation of underlying diseases in the general population of decontamination workers because hospitalised patients usually have more underlying diseases.

Our main interest was not to show a negative health impact of decontamination work environment, but to clarify the underlying health status of decontamination workers.

Comparative analysis could not be performed from this study.

This study presents the first investigation of underlying diseases in decontamination workers after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima.

Introduction

Occupational health is a global health issue.1 The WHO Global Plan of Action on Workers' Health highlights that the health of workers is determined not only by workplace hazards but also by social and individual factors, and access to health services.2 Half of the world's population is engaged in formal or informal employment, and may face certain health risks related to occupation; vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women, older persons and migrant workers may be more susceptible to these risks.2 It is therefore important to recognise vulnerable populations and take measures to protect all aspects of their health.

Migrant workers are an important vulnerable population because the migratory nature of their work can worsen their health.3 Migrant agricultural workers and miners are likely to be exposed to a wide variety of occupational risks3 4 because in addition to workplace hazards, they may have a low socioeconomic status (SES), as measured by their level of education, income and occupation.5 6 Lack of social and economic resources, exposure to occupational risk and poor access to health services may exacerbate unhealthy lifestyles, leading to a higher mortality rate due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in migrant workers.7 8 In order to improve the workplace health and safety of migrant workers, it is imperative to pay attention not only to primary prevention of occupational and work-related diseases and injury, but also to their overall health, which is not always related to work, including underlying communicable and NCDs, mental health, health promotion and improvement of their working environment.1 2 However, there is little information available on the health of migrant workers as the migratory nature of their employment makes proper investigation difficult.

Decontamination workers are a type of migrant workers who moved to the radio-contaminated areas of the Fukushima Prefecture after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) disaster, which followed a mega-earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011.9 10 These workers are essentially a type of Japanese temporary employees in construction and manufacturing, who constantly migrate across Japan to find new jobs.11 The number of decontamination workers in Fukushima Prefecture was ∼30 000 in 2015,12 and a considerable proportion of these workers are hired from other parts of Japan, due to a severe shortage of workers in Fukushima. Decontamination work is carried out in contaminated areas with the goal of minimising the level of external radiation to the general public.9 The work is generally carried out under the following working conditions: 8 hours of work per day, 5 days a week, with a 1-hour break per day. Workers are required to wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants and paper masks to prevent external or internal radio contamination.13 To assess excessive ionising radiation exposure dose among decontamination workers, dosimeters and the whole-body counter check-ups are adopted for external and internal exposures, respectively. The accumulated annual doses of the radiation exposure have been regularly surveyed, and the reported mean dose distribution of decontamination workers in the other studies was 0.6 mSv (max dose distribution 7.8 mSv) in 2015.12 14 15 In addition to the risk of radiation exposure,12 14 16 17 decontamination workers may face various other health risks such as developing NCDs, infection and injury. We previously reported a case of poor control of underlying disease and eventual death of a decontamination worker from sepsis, following infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae,13 highlighting the need for further understanding the incidence of NCDs such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus in this population.13 To date, there is limited research addressing these points.

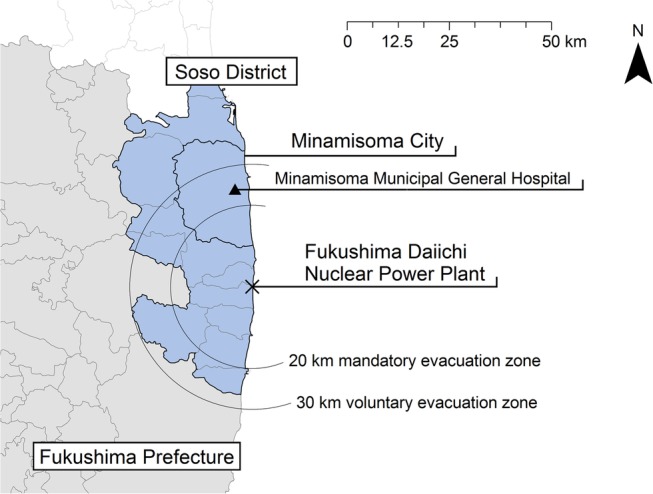

Minamisoma City, located 13–38 km from Fukushima Daiichi NPP, has seen a large influx of decontamination workers since 2012 (figure 1). The Minamisoma municipal government has hosted decontamination work in areas located 20–30 km from the NPP, while the Japanese central government has hosted work within the 20 km radius from the NPP.15 The large proportion of decontamination workers living in Minamisoma City, including those working within the 20 km radius from the NPP, may affect public health in that area. Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital (MMGH), located 23 km from Fukushima Daiichi NPP, plays an important role as a general hospital in the areas affected by Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Minamisoma City, MMGH, and the Fukushima Daiichi NPP, within Soso District of Fukushima Prefecture. The area within a 20 km radius from the NPP was designated a mandatory evacuation zone, and the area within a 30 km radius from the NPP was designated a voluntary evacuation zone, soon after the 3.11 disaster. MMGH, Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital; NPP, Nuclear Power Plant.

The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of NCDs among hospitalised decontamination workers, and whether NCDs were treated or not, in an area of the Fukushima Prefecture affected by the nuclear disaster.

Methods

Study population and definition of decontamination workers

To gain a comprehensive picture of the reasons for admission to the hospital and of the underlying health condition of migrant decontamination workers, we used the medical record database at MMGH to extract retrospective data on hospitalised patients who satisfied the following conditions: (1) was hospitalised to MMGH between 1 June 2012 (the initial day of decontamination work in Minamisoma City) and 31 August 2015; (2) had a recorded residential address outside of Soso District, the northern coastal area of Fukushima Prefecture where the hospital is located (figure 1); and (3) was working as a decontamination worker. We defined a patient as a decontamination worker if this information was included in their medical record, or if the company of their employment, as evident from medical insurance certificates, was one that regularly hired decontamination workers.

Data collection

From the medical records of the hospitalised decontamination workers, we extracted data on sex, age, residential address, diagnosis on admission, details of whether the condition leading to admission to the hospital had developed during work or not, presence of any underlying disease, alcohol consumption, smoking, marital status and medical insurance.

Outcome measures

We investigated the following outcome measures to assess the health of decontamination workers admitted to the hospital: underlying diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and diabetes, and their treatment status was assessed, to evaluate the prevalence and control of such diseases. In addition, lifestyle-related factors such as tobacco and alcohol consumption were investigated. To evaluate whether diagnoses on admission were influenced by underlying NCDs, we examined each diagnosis and noted whether the patient had developed the disease during work.

To define underlying NCDs, we used the following clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of each disease and information on the patients' use of medication, obtained from medical records: systolic blood pressure of ≥140, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 or the use of antihypertensive agents for treating hypertension; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol of ≥140 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of ≤40 mg/dL, triglyceride of ≥150 mg/dL or the use of antihyperlipidaemic agents for treating hyperlipidaemia; and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of ≥6.5%, blood glucose level of ≥220 mg/dL or the use of antihyperglycaemic agents for treating diabetes.18–20

To assess lifestyle-related factors, we classified patients based on their consumption of alcohol, into regular alcohol users and drinkers who consumed 40 g or more of ethanol a day, which is defined by the Japanese government as binge alcohol consumption.21 We classified patients based on their smoking status, into non-smokers, current smokers and smokers who smoked 15 cigarettes or more per day.22

We classified patients diagnosed on admission, with conditions caused by external factors, such as fractures and animal-related injuries into an external group, and those diagnosed with conditions affecting the internal organs into an internal group. We used the final diagnosis in cases where the final diagnosis was different from the diagnosis on admission.

We compared the prevalence of NCDs among unmarried and married decontamination workers to assess for any effect of marital status on health among the workers.

As to insurance coverage, although a universal health insurance system is implemented in Japan, if the patient visits a hospital due to industrial accident or traffic accident, other insurance is applied. We directly recorded the status of participant's health insurance.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the MMGH Institutional Review Board (approval number 27–14). Written informed consent was found to be unnecessary as this was a retrospective review of records. All data were anonymised prior to analysis.

Results

Among the 113 hospitalised patients who were engaged in decontamination work (112 male patients, median age of 54 years (age range: 18–69 years)), 98 patients (86.7%) were migrants from outside of Fukushima Prefecture. With respect to the demographics of underlying diseases, 57 (79.2%) of the 72 hypertensive patients (63.7%) were not treated before admission to the hospital. Similarly, among the 45 hyperlipidaemic patients (39.8%), 37 (82.2%) were untreated, and among the 27 hyperglycaemic patients (23.8%), 18 (66.7%) were untreated. The measured median value of systolic blood pressure was 140 mm Hg (value range 92–224 mm Hg). Eighty-three patients (73.5%) regularly consumed alcohol, with 28 (24.8%) drinking 40 g or more of ethanol per day, and 94 (83.1%) were current smokers. The number of patients who were not covered by Japanese health insurance, which in theory is to be provided for all people through the universal healthcare system, was as high as 11 (9.7%). Seventy-seven (68.1%) patients out of the total were unmarried (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among 113 hospitalised decontamination workers

| Characteristics | All patients (n=113) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (age range) | 54 | (18–69) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 112 | 99.1% |

| Female | 1 | 0.9% |

| Origination | ||

| Fukushima Prefecture | 15 | 13.3% |

| Other | 98 | 86.7% |

| Time the condition leading to admission developed | ||

| During work | 40 | 35.4% |

| Not during work | 73 | 64.6% |

| Alcohol use | ||

| User | 83 | 73.5% |

| Ethanol >40 g/day | 28 | 24.8% |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 94 | 83.1% |

| 15 Cigarettes/day or more | 64 | 56.6% |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Uninsured | 11 | 9.7% |

| Industrial accident | 14 | 12.4% |

| Traffic accident | 3 | 2.7% |

| Insured | 85 | 75.2% |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried* | 77 | 68.1% |

| Married | 36 | 31.9% |

| Underlying diseases | ||

| Hypertension | 72 | 63.7% |

| Untreated | 57 | 79.2%† |

| Treated | 15 | 20.8%† |

| Dyslipidaemia | 45 | 39.8% |

| Untreated | 37 | 82.2%‡ |

| Treated | 8 | 20.5%‡ |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 | 23.8% |

| Untreated | 18 | 66.7%§ |

| Treated | 9 | 33.3%§ |

| Measured values of blood pressure, body mass index, lipids, blood sugar and HbA1c | ||

| Median value | Value range | |

| Blood pressure (n=112) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure | 140 | 92–224 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 83.5 | 47–157 |

| Body mass index (n=79) | 23.8 | 18.1–42.5 |

| Lipids (n=65) | ||

| LDL cholesterol | 108 | 2–212 |

| HDL cholesterol | 48 | 14–99 |

| Triglyceride | 118 | 44–325 |

| Diabetes measures | ||

| Blood sugar (n=105) | 118 | 79–472 |

| HbA1c (n=71) | 5.8 | 4.4–12.1 |

*Divorced or never married.

†As a percentage of all hypertensive patients.

‡As a percentage of all dyslipidaemic patients.

§As a percentage of all diabetic patients.

Diagnoses on admission included 21 stroke cases, 19 infection cases, 8 seizure cases and 7 heatstroke cases among the 95 patients (84.1%) in the internal group. In this group, conditions developed during work only for 30 cases (31.6%). On the other hand, the leading cause of admission for the 18 patients (15.9%) in the external group was fracture (11 patients, 61.1%). In this group, the 10 conditions that developed during work included 4 fractures (40.0%), 4 hymenoptera stings (40.0%) and 2 conditions caused by other factors (table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnosis among the 113 hospitalised decontamination workers

| Developed during work | Developed outside work | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal group (ratio) | 30 (31.6%) | 65 (68.4%) | 95 |

| Stroke | 13 | 8 | 21 |

| Infection | 1 | 18 | 19 |

| Seizure | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Heat stroke | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| ACS | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Ileus | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Pancreatitis | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Subdural haemorrhage | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Cancer | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Others* | 2 | 14 | 16 |

| External group (ratio) | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | 18 |

| Fracture | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Hymenoptera sting | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Hemothorax | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Finger amputation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Abdominal injury | 0 | 1 | 1 |

*Includes cirrhosis, asthma, aortic dissection, gastrointestinal perforation, urinary stones, multiple myeloma, chronic subdural haematoma, gout, acute lumbar spine disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, atrophic gastritis, colon polyps, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, intestinal pneumonia, ulcerative colitis and migraine headaches.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of NCDs among unmarried and married decontamination workers. The rate of untreated hypertension among the unmarried population was significantly higher than that of married population (Fisher's test: p-value 0.002).

Table 3.

The incidence of NCDs among unmarried and married decontamination workers

| Unmarried population | Married population | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=77) | (n=36) | (Fisher's test) | |

| HT | 0.002 | ||

| Untreated HT | 43 (55.8%) | 14 (38.9%) | |

| Treated HT | 4 (5.2%) | 11 (30.6%) | |

| Non-HT | 30 (39.0%) | 11 (30.6%) | |

| DL | 0.408 | ||

| Untreated DL | 27 (35.1%) | 10 (27.8%) | |

| Treated DL | 4 (5.2%) | 4 (11.1%) | |

| Non-DL | 42 (54.5%) | 22 (61.1%) | |

| DM | 0.642 | ||

| Untreated DM | 13 (16.9%) | 5 (13.9%) | |

| Treated DM | 5 (6.5%) | 4 (11.1%) | |

| Non-DM | 59 (76.6%) | 27 (75.0%) |

DL, dyslipidaemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; NCDs, non-communicable diseases.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the proportion of untreated underlying diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus was 79.2%, 82.2% and 66.7%, respectively, among hospitalised decontamination workers, and that the proportion of decontamination workers admitted to MMGH with diseases affecting the internal organs (internal group) was 95 (84.1%); this number is much higher than the proportion of workers who were admitted due to diseases caused by external factors (external group, 18 patients, 15.9%). Furthermore, in the external group, conditions developed during work for 55.6% of the cases, whereas in the internal group, conditions developed during work for 31.6% of the cases.

In addition to protecting against workplace hazards such as traumatic injury, managing NCDs is essential for maintaining the health of the decontamination workers. In ∼80% of internal group patients, the proportion of diseases that developed during work was low (31.6%), suggesting that underlying conditions among workers may be common. Furthermore, a high proportion of alcohol users (73.5%), smokers (83.1%) and patients with untreated underlying disease was observed in the present study. Since it is known that frequent users of alcohol and tobacco have a higher mortality rate due to NCDs,8 it is highly important to prevent and control underlying diseases in this population. Although all decontamination workers are required to undergo a medical check-up every 6 months,15 the high proportion of workers with untreated diseases noted in this study suggests that this may not be an effective healthcare strategy for these workers. Furthermore, unhealthy lifestyles because of migration may have caused further deterioration of the workers' health; solitary migration to an unfamiliar place, which can lead to loss of social connections and poor dietary habits, may play a role in the deterioration of their health. In this regard, it is notable that the majority of the participants (68.1%) in the study were unmarried. In addition to improvement in working conditions, comprehensive and sustainable health support programmes for migratory populations are needed for managing underlying NCDs.

Decontamination workers may also face the risk of developing diseases caused by external factors such as work-related injuries. The proportion of work-related diagnoses was higher among the external group than among the internal group (55.6% vs 31.6%), suggesting a likelihood of workers being exposed to certain risks associated with decontamination work. This may be a natural finding as traumatic conditions tend to develop during work. In a previous study, immigrant agricultural workers were shown to face the risk of certain kinds of traumatic injuries due to a lack of work experience.23 It may be presumed that the migrant decontamination workers face similar risks. However, in the case of Fukushima, specific health problems such as hymenoptera stings may be related to the abandonment of contaminated areas24 and subsequent expansion of animal habitats. In all, further understanding of the specific risks involved and finding ways to prevent traumatic injuries in decontamination workers are both necessary to improve the workplace health and safety of the workers.

Decontamination work may be associated with low-socioeconomic-background workers, which may carry additional health risks. Low SES is associated with a high risk of developing various underlying chronic diseases,6 25 26 and our previous case report on a decontamination worker also suggested a possible association between a decontamination worker's low SES and deterioration of his health as a result of underlying disease.13 Among the general population in Japan, it is estimated that only 1% of the people are not covered by Japanese health insurance;27 yet the rate of non-coverage among decontamination workers was ∼10% in this study, which is substantially higher than that among the general population. Non-coverage by Japanese health insurance is higher among low-income households, households under unemployed or unstable employment conditions, and single-mother households.28 We speculate that unstable employment conditions such as day labour, and an unsure salary which is highly liable to be affected by weather due to day, may contribute to socioeconomic disadvantage among this group and be associated with the non-coverage of health insurance among decontamination workers.29 Moreover, the proportion of unmarried decontamination workers was as high as 68.1%, while it was 38.9% in the general population.30 Decontamination workers may occupy a position of disadvantage in Japanese society, and we suggest that future studies are necessary to accurately estimate the socioeconomic background of these workers and evaluate its possible association with their health outcomes.

The present study is the first investigation of underlying diseases in decontamination workers hired following the nuclear disaster in Fukushima. However, this study is limited by three main factors. First, although we had tried to compare the study participants with healthy workers or other hospitalised patients to support our hypothesis that there is a high prevalence of untreated NCDs among the hospitalised workers noted in this study, we were unable to collect this data for analysis. MMGH plays an important role as a general hospital in the area affected by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and it has treated decontamination workers who developed various diseases, allowing us to collect our original data. Unfortunately, data regarding other hospitalised patients (eg, a control population) were not available to this study due to lack of ethics approval to the database. In addition, not all data are computerised, meaning that potential for collection and analysis of data can be limited within the capacity of our hospital. In an attempt to obtain the health check-up results of general decontamination workers, we asked companies employing decontamination workers and Minamisoma local government but finally failed to obtain the data of the result due to lack of their consent. The above factors should be recognised as both limitations to this study, and suggestions for further research. Second, only the decontamination workers admitted to one hospital were studied, and the limited number of the study participants may have caused sampling bias. Third, only the decontamination workers from outside Soso District were included, in order to specifically study migrant workers. This may have led to an overestimation of the true burden of underlying disease in decontamination workers as our results do not reflect the health of all the workers. Further investigation is warranted to examine the health status of all types of decontamination workers.

Conclusions

A high burden of underlying NCDs was found in hospitalised decontamination workers in Fukushima. Managing underlying NCDs such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus among decontamination workers is essential. Further investigation is necessary to shed light on the health status of decontamination workers in Fukushima, in addition to identifying the effect of long-term radiation exposure on these workers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Shun Ishikawa and Mr Yoshiaki Yokota for teaching us about the working conditions of decontamination workers in Minamisoma city.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceptualised and designed the study. TS collected the data. TS, MT, AO, CL, SN and SK interpreted the data. SN made the figures. TS wrote the manuscript, and all the authors contributed to making critical revisions for improving the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Connecting health and labour: what role for occupational health in primary health care. World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Workers’ health: global plan of action. World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mobed K, Gold EB, Schenker MB. Occupational health problems among migrant and seasonal farm workers. West J Med 1992;157:367–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce S. Major issues in miner health. Environ Health Perspect 1998;106:A538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muennig P, Sohler N, Mahato B. Socioeconomic status as an independent predictor of physiological biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: evidence from NHANES. Prev Med 2007;45:35–40. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh RB, Sharma JP, Rastogi V et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in the Indian social class and heart survey. J Hum Hypertens 1997;11:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nandi SS, Dhatrak SV, Chaterjee DM et al. Health survey in gypsum mines in India. Indian J Community Med 2009;34:343–5. 10.4103/0970-0218.58396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid PJ, Sluis-Cremer GK. Mortality of white South African gold miners. Occup Environ Med 1996;53:11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiraoka K, Tateishi S, Mori K. Review of health issues of workers engaged in operations related to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. J Occup Health 2015;57:497–512. 10.1539/joh.15-0084-RA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsuru A, Tanigawa K, Kumagai A et al. Nuclear disasters and health: lessons learned, challenges, and proposals. Lancet 2015;386:489–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60994-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich MR, Frumkin H. An overview of Japanese occupational health. Am J Public Health 1988;78:809–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dose distribution among workers engaged in decontamination and related works 2016. http://www.rea.or.jp/chutou/koukai_jyosen/H27nen/English/honbun_jyosen-h27-English.html (accessed 17 Oct 2016).

- 13.Sawano T, Tsubokura M, Leppold C et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis deteriorated by uncontrolled underlying disease in a decontamination worker in Fukushima, Japan. J Occup Health 2016;58:320–2. 10.1539/joh.15-0292-CS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsubokura M, Nihei M, Sato K et al. Measurement of internal radiation exposure among decontamination workers in villages near the crippled Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Health Phys 2013;105:379–81. 10.1097/HP.0b013e318297ad92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasui S. Establishment of new regulations for radiological protection for decontamination work involving radioactive fallout emitted by the Fukushima Daiichi APP accident. J Occup Environ Hyg 2013;10:D119–24. 10.1080/15459624.2013.818239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimura T, Yamaguchi I, Terada H et al. Radiation occupational health interventions offered to radiation workers in response to the complex catastrophic disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. J Radiat Res 2015;56:413–21. 10.1093/jrr/rru110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimura T, Yamaguchi I, Terada H et al. Public health activities for mitigation of radiation exposures and risk communication challenges after the Fukushima nuclear accident. J Radiat Res 2015;56:422–9. 10.1093/jrr/rrv013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014;311:507–20. 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Abbreviated report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japan Atherosclerosis Society Guidelines for diagnosis and prevention of arthrosclerosis cardiovascular diseases. Japan Atherosclerosis Society, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare A basic direction for comprehensive implementation of national health promotion. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolstrup JS, Hvidtfeldt UA, Flachs EM et al. Smoking and risk of coronary heart disease in younger, middle-aged, and older adults. Am J Public Health 2014;104:96–102. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebman AK, Juarez-Carrillo PM, Reyes IA et al. Immigrant dairy workers’ perceptions of health and safety on the farm in America's Heartland. Am J Ind Med 2016;59:227–35. 10.1002/ajim.22538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hymenoprteran strings in evacuation areas. Fukushima Minyu 19 August 2015, 2015.

- 25.Grotto I, Huerta M, Grossman E et al. Relative impact of socioeconomic status on blood pressure lessons from a large-scale survey of young adults. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:1140–5. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velasquez E, Adela Baron M, Solano L et al. Lipid profile in Venezuelan preschoolers by socioeconomic status. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2006;56:22–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Report of public pension coverage in 2013. Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiroyuki Kawaguchi MI. Utilization of medical service coverage in low-income households. Med Econ Surv Organ 2010;22:17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukushima Minyu Land mark of rehabilitation “Workers” (Fukkounomichishirube Sagyouin). Fukushima Minyu 2016, 2016.

- 30.National Institute of Population and Social Security Research Sex, marital status over 15 year-old in Japan. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2016. [Google Scholar]