Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence of knee pain among 3 major ethnic groups in Malaysia. By identifying high-risk groups, preventive measures can be targeted at these populations.

Design and setting

A cross-sectional survey was carried out in rural and urban areas in a state in Malaysia. Secondary schools were randomly selected and used as sampling units.

Participants

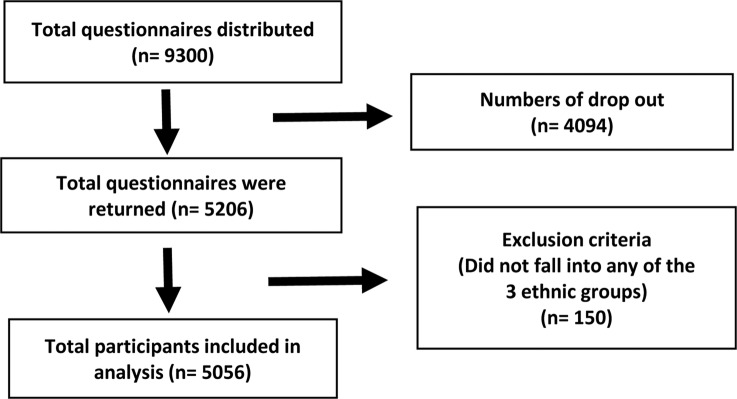

Adults aged ≥18 years old were invited to answer a self-administered questionnaire on pain experienced over the previous 6 months. Out of 9300 questionnaires distributed, 5206 were returned and 150 participants who did not fall into the 3 ethnic groups were excluded, yielding a total of 5056 questionnaires for analysis. 58.2% (n=2926) were women. 50% (n=2512) were Malays, 41.4% (n=2079) were Chinese and 8.6% (n=434) were Indians.

Results

21.1% (n=1069) had knee pain during the previous 6 months. More Indians (31.8%) experienced knee pain compared with Malays (24.3%) and Chinese (15%) (p<0.001). The odds of Indian women reporting knee pain was twofold higher compared with Malay women. There was a rising trend in the prevalence of knee pain with increasing age (p<0.001). The association between age and knee pain appeared to be stronger in women than men. 68.1% of Indians used analgesia for knee pain while 75.4% of Malays and 52.1% of Chinese did so (p<0.001). The most common analgesic used for knee pain across all groups was topical medicated oil (43.7%).

Conclusions

The prevalence of knee pain in adults was more common in Indian women and older women age groups and Chinese men had the lowest prevalence of knee pain. Further studies should investigate the reasons for these differences.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, RHEUMATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

-

▪

The sample size was large and comprised of sufficient numbers of the different ethnicity groups in Malaysia.

Population were parents with children and might be different for non-parents.

We were unable to attribute knee pain being entirely due to osteoarthritis.

We did not collect data on other confounding factors such as body mass index, psychosocial factors, history of trauma, and menopausal status.

Although we did not perform a formal sample size calculation, our sample size was large and it was comparable to another study.1

Introduction

Knee pain is the most common pain problem among older individuals and the most frequent cause of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knees.1 2 OA of the knee impacts on quality of life and causes physical disability as well as limitations in functioning in older individuals.3 4 Studies have shown that there are differences in the prevalence of knee pain based on OA among different ethnic groups.5–9 In the Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD) survey, 13.1% Indian women had knee pain compared with 11.1% Malay women and 5.8% Chinese women (5.8%).5 A study in the USA showed that knee pain was disproportionately higher among older African-Americans than non-Hispanic white groups.8

Cultural background, pain threshold, and genetic predisposition may be some of the reasons why knee pain is more common in certain ethnic groups. Importantly, many environmental and lifestyle risk factors are reversible (eg, obesity, muscle weakness) or avoidable (eg, occupational or recreational joint trauma) which has implications for primary and secondary preventions.

The aim of our study was to describe the prevalence of knee pain and use of analgesic medications for knee pain among different ethnic groups in Malaysia as well as the interaction and association of sociodemographic information to the prevalence of knee pain. Identifying the high-risk groups would assist healthcare workers in understanding patients' experiences with and beliefs on pain, and hence preventive measures could be targeted to these groups of people.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was carried out in six districts in the State of Selangor in Malaysia based on purposive sampling in four urban districts (Petaling Jaya, Subang, Seri Kembangan, Kampong Medan) and two rural towns in Kuala Langat district (Banting and Jenjarom). The districts were selected based on ethnic distribution as well as socioeconomic status. Secondary schools within these districts were randomly selected and used as sampling units to reach out to the adults in the community. The children from the selected schools were provided with self-administered questionnaires for their parents or main caregivers aged 18 years and above to complete. Efforts were made to optimise the response rate through reminders and providing incentives to schools which were able to achieve an at least 70% response rate. The questionnaires were collected 2 weeks after distribution. Out of the 9300 questionnaires distributed, 5206 were returned, yielding a response rate of 56%. However, we excluded 150 participants who were not part of any of the three key ethnic groups (Chinese, Malays and Indians), leaving a total of 5056 questionnaires for analysis. The findings are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection of participants.

We did not address the issue of non-respondents as the sample size was large (n=5056) and we believed that it would not affect the findings of the study. Furthermore we did not have the non-respondents' contact numbers as the questionnaires were distributed to the students for them to bring home to their parents or main caregivers.

The researchers designed the self-administered questionnaires based on the existing literature and discussion. Sociodemographic data (including age, sex, occupation, education level, location of residency, and ethnicity), types of pain experienced over the previous 6 months, and medications used were captured. All of the data, including ethnicity and types of pain were self-declared. The English questionnaires were translated into two other languages (Malay and Chinese) and then back-translated. Any discrepancy in translation was discussed and agreed on by the three researchers. This was followed by pilot-testing on adults of different ethnicities, mainly Malay, Chinese and Indians, and further revisions were made before the survey was distributed.

We also were given permission from the schools and State Education Department. Written informed consent was acquired from all the participants.

We classified occupation based on employment status, either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for the data analyses, and educational level as primary and non-formal, secondary and tertiary. We also categorised the participants into three main age groups, being ≤30, 31–40 and >40 years old.

Stratification of rural areas was based on the census from Malaysia in 2010 that defined as rural areas as having populations <10 000 people and featuring agriculture and natural resources. Urban areas were defined as gazette areas with populations of 10 000 and more.10

Data analysis

Categorical data were reported in proportions (percentage). Continuous data were described as means and SDs if the distribution were Gaussian. The χ2 analyses were employed to determine significant group differences with knee pain prevalence. Binary logistic regression analyses examined the relationship between ethnicity and knee pain controlling for other sociodemographic variables. Crude and adjusted OR (AOR) and 95% CI are presented. Significance was set at an α level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.16.0.

Multivariate analyses were first performed using all combined data. A hierarchical regression strategy was used in which the independent variables were forced into the equation: (I) ethnicity alone (model 1); (II) the main effects of all independent variables (model 2); and finally (III) main effects including all possible two-way interactions terms with ethnicity (model 3) to determine the presence of interaction effect. The two-way interactions between (I) ethnicity and gender; and (II) gender and age were statistically significant. Subsequent regression analyses were therefore stratified by gender. With the gender-specific regression analyses, a similar hierarchical approach was applied. As none of the two-way interaction terms were found to be significant in these models, only the results of the main effects were presented in the final model for each gender. All data and findings are fully available without restriction.

Results

A total of 5056 participants responded to the questionnaire. The mean age of the participants was 38.5 (SD±8.95) with men (mean age=40.6, SD±9.2) being slightly older than women (mean age=36.9, SD±8.46). Table 1 shows the overall sociodemographic distribution of participants and their association with knee pain. The majority of respondents were Malays (50%) followed by Chinese (41.4%) and Indians (8.6%). The sample was mostly women, from urban residences, had secondary and higher education levels and employed.

Table 1.

Respondents' characteristics by prevalence of knee pain (N=5056)

| Knee pain, N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall | Yes | No | p Value |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Malay | 2512 (50.0) | 610 (24.3) | 1902 (75.7) | |

| Chinese | 2079 (41.4) | 311 (15.0) | 1768 (85.0) | |

| Indian | 434 (8.6) | 138 (31.8) | 296 (68.2) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| <30 | 846 (16.8) | 129 (15.2) | 717 (84.8) | |

| 31–40 | 1936 (38.3) | 392 (20.2) | 1544 (79.8) | |

| >40 | 2268 (44.9) | 546 (24.1) | 1722 (75.9) | |

| Gender | 0.730 | |||

| Male | 2103 (41.8) | 440 (20.9) | 1663 (79.1) | |

| Female | 2926 (58.2) | 624 (21.3) | 2302 (78.7) | |

| Residence | <0.001 | |||

| Urban | 3250 (64.3) | 641 (19.7) | 2609 (80.3) | |

| Rural | 1806 (35.7) | 428 (23.7) | 1378 (76.3) | |

| Education | 0.022 | |||

| Tertiary | 766 (32.2) | 302 (18.7) | 1310 (81.3) | |

| Secondary | 2631 (52.5) | 580 (22.0) | 2051 (78.0) | |

| Primary or non-formal | 1612 (15.3) | 172 (22.5) | 594 (77.5) | |

| Employment status | 0.485 | |||

| Yes | 3208 (69.9) | 683 (21.3) | 2525 (78.7) | |

| No | 1382 (31.1) | 307 (22.2) | 1075 (77.8) | |

The overall prevalence of knee pain among all respondents was 21.2%. The prevalence of knee pain differed significantly with age, ethnicity, urban-rural area and educational level (see table 1).

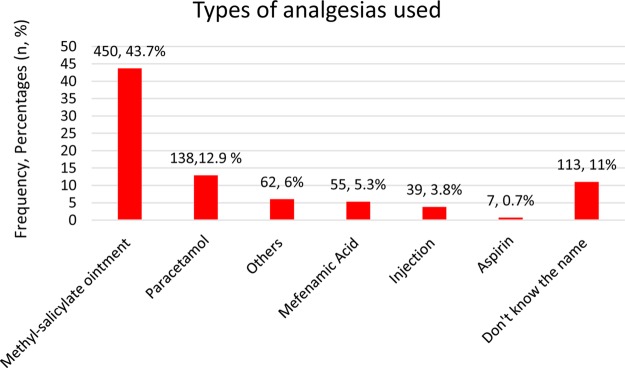

Overall 21.1% (n=1069) of respondents had knee pain. The Indian population (31.8%, n=138) had the highest prevalence of knee pain, followed by Malays at 24.3% (n=610) and Chinese at 15% (n=311). Two-thirds (67.6%, n=716) used medications for their knee pain over the previous 6 months. Malays (75.4%, n=460) were more likely to use medications than Indians (68.1%, n=94) and the Chinese (52.1%, n=162) (p<0.001), depicted in table 2. Figure 2 lists the medications used which included topical methyl-salicylate ointment (43.7%), paracetamol (12.9%), mefenamic acid (5.3%), and injections (3.8%).

Table 2.

Comparison of ethnic groups using analgesia for knee pain (N=716/1069)

| Knee pain on analgesia, N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Yes | No | p Value |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Malay | 460 (75.4) | 150 (24.6) | |

| Chinese | 162 (52.1) | 149 (47.9) | |

| Indian | 94 (68.1) | 44 (31.9) | |

Figure 2.

Types of analgesics used for knee pain (N=716).

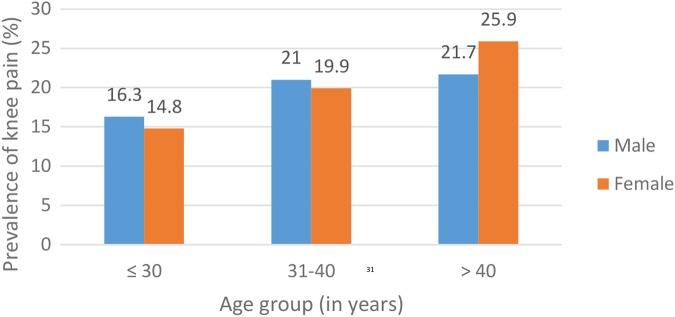

Subgroup analyses by gender suggested that the overall prevalence of knee pain significantly increased with age among women (p<0.001) but not among men (p=0.102) (figure 3). With the stratified analysis by ethnicity, there was no significant difference found between gender and knee pain except among Indians. Indian women reported significantly higher levels of knee pain than Indian men. An increasing prevalence of knee pain with increasing age (p<0.001) was observed among the Malays and Chinese but not among those of Indian ethnicity (table 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of knee pain by gender and age group.

Table 3.

Ethnic distribution of knee pain by gender and age group

| Prevalence (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender |

Age (in years) |

||||||

| Ethnic | Male | Female | *p Value | ≤30 | 31–40 | >40 | †p Value |

| Malay | 24.8 | 23.7 | 0.543 | 17.9 | 21.7 | 29.0 | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 13.9 | 15.7 | 0.304 | 11.0 | 13.8 | 17.4 | 0.004 |

| Indian | 22.9 | 39.4 | <0.001 | 31.0 | 34.1 | 29.9 | 0.683 |

*p Value derived from comparing gender difference in each ethnic category.

†p Value derived from comparing age group difference in each ethnic category.

In multivariate analysis (table 4), the unadjusted OR (model 1) indicated that ethnicity, age, residence and education level were associated with knee pain. Gender and employment status of the respondents did not have an influence on knee pain. However, gender became statistically significant after adjusting for other confounding variables. The main effect model (model 2) demonstrated that compared with men, the odds of reporting knee pain among women were higher by 23%. The odds of knee pain were 49% lower among the Chinese and 42% greater among Indians compared with Malays versus the <30 years age group, the odds of reporting knee pain were higher among those above 40 years age group (AOR=1.60, 95% CI 1.26 to 2.02). When all possible two-way interaction terms were added in the regression analysis, the association between knee pain with ethnicity, gender and age group diminished (model 3). There was significant effect modification between knee pain and ethnicity by gender. Similarly, there was age by gender interaction.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted OR and 95% CI of knee pain by socioeconomic factors

| Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Associated factor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (Ref) | |||

| Female | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.18) | 1.23 (1.04 to 1.45) | 0.69 (0.44 to 1.11) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay (Ref) | |||

| Chinese | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.64) | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.61) | 0.31 (0.14 to 0.68) |

| Indian | 1.45 (1.17 to 1.81) | 1.42 (1.12 to 1.78) | 1.46 (0.55 to 3.91) |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤30 (Ref) | |||

| 31–40 | 1.41 (1.14 to 1.75) | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.51) | 1.10 (0.69 to 1.75) |

| >40 | 1.76 (1.43 to 2.18) | 1.60 (1.26 to 2.02) | 1.26 (0.81 to 1.96) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban (Ref) | |||

| Rural | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91) | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.16) | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.12) |

| Education | |||

| Tertiary (Ref) | |||

| Secondary | 1.26 (1.02 to 1.55) | 1.37 (1.07 to 1.75) | 1.47 (1.03 to 2.11) |

| Primary or non-formal | 1.23 (1.05 to 1.43) | 1.23 (1.04 to 1.45) | 1.33 (1.07 to 1.66) |

| Employment status | |||

| No (Ref) | |||

| Yes | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.23) | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) |

| Ethnicity×gender | |||

| Chinese×female | – | – | 1.22 (0.83 to 1.79) |

| Indian×female | – | – | 2.09 (1.21 to 3.60) |

| Gender×age group | |||

| Female×age group (31–40) | – | – | 1.24 (0.75 to 2.07) |

| Female×age group (>40) | – | – | 1.96 (1.21 to 3.17) |

Model 1: adjusted for other factors shown in the table.

Model 2: adjusted for other factors.

Model 3: adjusted for all possible two-way interactions terms with ethnicity. Only interaction terms that were significant are presented.

Subsequent gender specific multivariate analyses (table 5) suggested that Chinese men reported significantly less knee pain than Malay men. Chinese women were less likely to report knee pain (AOR 0.54; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.68), while the odds of Indian women reporting knee pain were twice as high compared with Malay women. The association between age and knee pain appeared to be stronger in women than in men. The odds of reporting knee pain were twofold higher among older women (>40 years above) compared with younger women. Lower education level (primary or lower) was associated with knee pain in men but this was not observed in women.

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted OR and 95% CI of knee pain by socioeconomic factors stratified by gender

| Male |

Female |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated factor | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Malay (Ref) | ||||

| Chinese | 0.49 (0.38 to 0.63) | 0.47 (0.36 to 0.63) | 0.59 (0.49 to 0.73) | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.68) |

| Indian | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.28) | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.31) | 2.09 (1.56 to 2.80) | 2.02 (1.48 to 2.76) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤30 (Ref) | ||||

| 31–40 | 1.37 (0.94 to 1.99) | 1.13 (0.74 to 1.73) | 1.43 (1.10 to 1.87) | 1.32(0.98 to 1.77) |

| >40 | 1.45 (1.03 to 2.05) | 1.20 (0.81 to 1.76) | 2.10 (1.60 to 2.76) | 2.11(1.55 to 2.87) |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban (Ref) | ||||

| Rural | 0.78 (0.63 to 0.96) | 0.76 (0.49 to 1.16) | 0.82 (0.69 to 1.00) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.16) |

| Education | ||||

| Tertiary (Ref) | ||||

| Secondary | 1.18 (0.85 to 1.64) | 1.36 (0.92 to 2.01) | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.11) | 1.28 (0.93 to 1.77) |

| Primary or non-formal | 0.85 (0.59 to 1.21) | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.82) | 0.77(0.59 to 1.00) | 1.12(0.89 to 1.41) |

| Employment status | ||||

| No (Ref) | ||||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.79 to 1.73) | 0.76 (0.49 to 1.16) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.27) |

Models were adjusted for other factors shown in the table.

Discussion

Knee pain is a common medical problem in the community. We found that nearly one-third of the Indian population had knee pain compared with other ethnic groups (p<0.001), especially Indian women who reported knee pain twofold more compared with Malay women (AOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.48 to 2.76). This was also seen in the COPCORD survey where 13.1% of Indian women experienced knee pain compared with Malay women (11.1%) and Chinese women (5.8%).5 11 Another local study conducted also showed that prevalence of pain among the Indian ethnic group was greater compared with Malay and Chinese in both public primary care clinics and general practice clinic settings.9 These findings may point to possible genetic factors and cultural backgrounds determining response to pain among the Indian population. Perceptions towards pain threshold are greatly affected by family members, peers, and cultural background. Bone mineral density plays an important role in the development of arthritis and sclerosis, as evidence in a work by Allen et al.6 They also showed that forces experienced during walking by certain ethnic groups will cause knee OA. For instance, African-Americans were more likely than Caucasians to have valgus thrust during walking, causing more knee OA.

Yet, more research needs to be carried out to examine these observations more closely. In our study, the Chinese ethnicity especially Chinese men (AOR 0.47, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.63) had the lowest prevalence of knee pain and this was again consistent with another study which also found a lower prevalence of knee pain among the Chinese.5 This could be due to their culturally based response to pain and genetic factors as well as their beliefs in using complementary medicines widely available among Chinese populations such as acupuncture and thermal cupping.

Although our study did not specifically determine the cause of knee pain, we found that knee pain was more common in the older age groups suggesting that the aetiology could be OA.12–15 In particular, we observed that the odds of knee pain were two times higher among older women compared with younger women (AOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.55 to 2.87).

There was more knee pain among those with lower educational levels, especially men with primary and non-formal education levels and this could be due to lack of awareness and knowledge about access to healthcare services for the prevention of knee OA. Besides, it may arise from the types of works undertaken by those without tertiary education whereby more stress may have been placed on their knees because of their strenuous jobs, hence causing more knee pain in this particular population.

Our study demonstrated that gender became statistically significant only after adjustment for other confounding variables. The main effect model (model 2) showed that compared with men, the odds of reporting knee pain among women were higher by 23% (95% CI 1.04 to 1.45). Pain thresholds of women were determined to be lower than that of men in one of the studies by Cepeda et al.16 A meta-analysis showed that gender stereotypes have a significant influence on pain sensitivity and pain threshold.16 17

Our study did not find any significant difference in the prevalence of knee pain in the context of employment status, despite adjusting for other confounding variables or according to gender. However, several studies found that socioeconomic status14 and psychological factors18 19 were determinants of knee pain and physical function.20 The COPCORD survey showed that housewives (unemployed) reported more musculoskeletal pain and this may be related to repetitive household tasks and psychological stresses.5 In our study there was also no difference in prevalence of knee pain based on whether one was living in a rural or urban environment. Yet, other studies have found that there are more musculoskeletal symptoms in socially deprived areas.21 The prevalence of knee pain in our rural community (23.7%) was higher than that of a study done in rural South India (17.2%).22 This may be the result of a wide variation in the definition of rural or urban areas among different countries.

Although we did not collect data on other confounding factors such as psychosocial factors, body mass index13 18 23–25 and menopausal states11 26 with regard to knee pain, these variables have been shown to impact perceptions of knee pain.

Among those who had reported having knee pain in our study, though Indians had more knee pain, Malays were more prone to analgesic use. This could be because more Indians were from rural areas and from the lower socioeconomic classes, hence have poor knowledge with respect to accessing healthcare services for their knee pain. The medication most commonly used was a topical agent possibly because it was cheaper to obtain and more readily available as over the counter medication. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) require a physician's prescription. With an ageing population and rising number of consultations for knee pain, future studies should attempt to understand public perceptions, awareness and knowledge of self-care of knee pain and investigate the factors that influence patients seeking help.

In summary, our study found that Indian women had a higher prevalence of knee pain compared with other ethnic groups. It is important to target this high-risk group so that prevention and appropriate interventions can be provided early. Murphy et al13 had suggested that prevention programmes should be offered relatively early in life and that there should be dissemination of understanding the need of healthcare utilisation in diagnosing early knee OA within communities.

Future studies should look at other confounding factors such as other comorbid conditions, genetic predisposition, psychosocial factors and medical access factors as well as more precise assessment for tools in diagnosing knee pain in the primary care setting.

Conclusion

Prevalence of knee pain was more common in the Indian ethnic group especially among Indian women. It was also more frequently reported in the older women age groups, though was least prevalence among Chinese men. The most common medication used for knee pain was topical medicated oil. Further studies need to be carried out to explore the reasons for these differences.

Footnotes

Contributors: YCC had fulfilled all three of the ICMJE guidelines for authorship, contributing the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. She also drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. HCB, had also fulfilled in acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. She also drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. CJN had also fulfilled all three of the ICMJE guidelines for authorship, contributing the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. CLT involved in acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data for this study. NSH, had also contributed the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis, and interpretation of data. WYC had also fulfilled the criteria for authorship in acquisition of data, or analysis, and interpretation of data. SMC, too fulfilled the criteria for authorship in acquisition of data, or analysis, and interpretation of data.

Funding: This study was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Glaxo Smith Kline Pharmaceutical company (GSK PCM-UMMC 002).

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Malaya Medical Center Medical Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kim IJ, Kim HA, Seo YI et al. Prevalence of knee pain and its influence on quality of life and physical function in the Korean elderly population: a community based cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci 2011;26:1140–6. 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muraki S, Akune T, En-Yo Y et al. Joint space narrowing, body mass index, and knee pain: the ROAD study (OAC1839R1). Osteoarthr Cartil 2015;23:874–81. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health 1994;84:351–8. 10.2105/AJPH.84.3.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jover JA, Lajas C, Leon L et al. Incidence of physical disability related to musculoskeletal disorders in the elderly: results from a primary care-based registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:89–93. 10.1002/acr.22420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veerapen K, Wigley RD, Valkenburg H. Musculoskeletal pain in Malaysia: a COPCORD survey. J Rheumatol 2007;34:207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen KD. Racial and ethnic disparities in osteoarthritis phenotypes. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010;22:528–32. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833b1b6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Almeida Y, Sibille KT, Goodin BR 3rd et al. Racial and ethnic differences in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;66:1800–10. 10.1002/art.38620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26–35. 10.1002/art.23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zailinawati AH, Teng CL, Kamil MA et al. Pain morbidity in primary care—preliminary observations from two different primary care settings. Med J Malaysia 2006;61:162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Social and Demographic Statistics: Classifications of Size and Type of Locality and Urban/Rural Areas. United Nations Statistics Division2012 [updated 2012].[Table 6]. Available from: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/dyb2005.htm.

- 11.Kudial S, Tandon VR, Mahajan A. Rheumatological disorder (RD) in Indian women above 40 years of age: a cross-sectional WHO-ILAR-COPCORD-based survey. J Midlife Health 2015;6:76 10.4103/0976-7800.158955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicole Elliott MB, Martin Allaby. Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59: 1207–13. 10.1002/art.24021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jinks C, Vohora K, Young J et al. Inequalities in primary care management of knee pain and disability in older adults: an observational cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50: 1869–78. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jinks C, Jordan K, Ong BN et al. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST). 2. Results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cepeda MS, Carr DB. Women experience more pain and require more morphine than men to achieve a similar degree of analgesia. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1464–8. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000080153.36643.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley JL III, Robinson ME, Wise EA et al. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain 1998;74:181–7. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00199-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jinks C, Jordan KP, Blagojevic M et al. Predictors of onset and progression of knee pain in adults living in the community. A prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:368–74. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2428–9. 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thumboo J, Chew LH, Lewin-Koh SC. Socioeconomic and psychosocial factors influence pain or physical function in Asian patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:1017–20. 10.1136/ard.61.11.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:649–55. 10.1136/ard.57.11.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul BJ, Rahim AA, Bina T et al. Prevalence and factors related to rheumatic musculoskeletal disorders in rural south India: WHO-ILAR-COPCORD-BJD India Calicut study. Int J Rheum Dis 2013;16:392–7. 10.1111/1756-185X.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunlop DD, Semanik P, Song J et al. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1274–82. 10.1002/art.20968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Cirillo PA et al. Body weight, body mass index, and incident symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Epidemiology 1999;10:161–6. 10.1097/00001648-199903000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neogi T, Nevitt MC, Yang M et al. Consistency of knee pain: correlates and association with function. Osteoarthr Cartil 2010;18:1250–5. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salve H, Gupta V, Palanivel C et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis amongst perimenopausal women in an urban resettlement colony in South Delhi. Indian J Public Health 2010;54:155–7. 10.4103/0019-557X.75739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]